Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2857)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2353)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1388)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (1840)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2569)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1923)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (169)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1672)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (233)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (519)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3567)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4745)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (31)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (12)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (215)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (981)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2117)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (84)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (184)

- Envelopes (73)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (815)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (5926)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (5)

- Portraits (4535)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (151)

- Publications (documents) (2305)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (15)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Vitreographs (129)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (373)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1407)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1784)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (170)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (110)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (1876)

- Dams (107)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1184)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (45)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (118)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (71)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

Western Carolinian Volume 61 Number 07 (08)

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

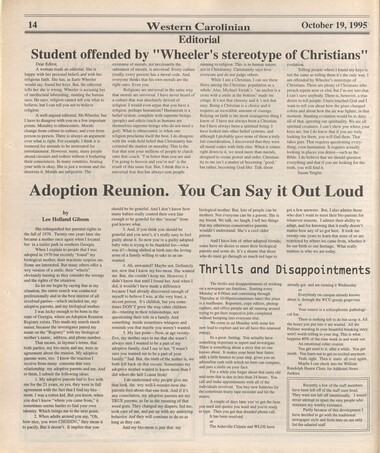

16 invisible academy I 10.19.95 Meschach McLachlan: 4 Poems "here the cocoon begins and ends with the silkworm's death what is said and what is not in all that was said and was not" —Emmanueal HocquardfTranlation by Michael Palmer) We will be unseen in something, in some place where buildings arrow paradormic streets with cubic hearts the color of light. There will be trees a little ways off. There will be sounds only noticeable from the way the unspeakmg feels: uncomfortable with what it will do—with the sadness and the trouble of when people are together and it is terrible not to talk. There will be grains of dogs, off the lawns straying like colorless misshapen pots from the third grade. The third grade is now a mean eyeball with gigantic knees, its fat toes corned with learning to draw from cheap sandal feet with scabless skin—I think my teacher had hair like indistinct smells from another room, my mother standing in the way she sometimes cooked: beyond my sight. It is the smell and the toes I remember. In another arm of the town out of ken there is a funny blob like a boiled peach that pulses and stinks and has no lips, no way in. It is panting the pave. It is tired of growing sleep. There are awkward cans beside, pretending to move. The frightened boy is standing outside of eating inside somewhere in another nipple of what is now a city. He has dyed his hair red because of a splotchy girl, invisible to the city also. He enters and barnacles a table. Pays for coffee in nickels. I think of him in the town that sips on neither of us any longer because of his being cigarette breasted and coughing. A dog collar around his neck he said he was too skinny for god anymore, while I fumbled through my backpack for a book, barely listening. He would always know the waitresses by name and leave them poems for tips. I would sit, shifting a little in the menopausal air of after midnight, being too close to tired to do anything but laugh like a drowning bee from when I was three during a summer like not many, memorable, when I took the muffled black and yellow from an apivorous wet to the tiny pool's partitions and felt the first sex, the painful penetration, the crying. It was the last time I was to see him closer than the cities we are ageless in when I stopped laughing and said goodbye near the first phenomena of day. He had set out walking with a made up girl, funny in less life than she deserved, over a fragmented silver that ruined shop signs along the curdling streets, a bruised sky beneath the odor of them. "McLachlan Poems" Continued on Page 17 Ryan Wilkinson's: The Church type "AH those kids think they're so holier than thou 'cause they go to that big church," Johnny said. His lip snarled in disgust. "Man, I go to church every Sunday." I laughed because I thought he was joking. He stopped walking and just stared at me. The smile slowly faded from my face. I didn't want to piss him off. Johnny Stevens was one of the meanest kids in the eighth grade and it made me nervous just standing near him much less talking to him. "What are you laughing at," he said. "I don't know I guess you just don't look like the church type." I hadn't been to church in four years. Not since my parents got divorced. I think after the divorce my mom, kind of, lost the faith you might say. "Yeah, well I guess not," he said. "I guess when you think of the church type you think of them." He motioned to a group of about ten or twelve kids. They were what kids like Johnny referred to as "snobs". "Look at 'em. With their cute, little button-down shirts and their brown loafers. God, gimme a break. I bet they all think they're going straight to Heaven when they die. Man, are they gonna be in for a surprise." "Why wouldn't they go to Heaven?" I asked. He snarled his lip again and looked at me like I was crazy. "Do you think you're going to Heaven?" he asked. "Well, I just figured that if you're good to people and you believe in God then you went to Heaven." Johnny smiled. "Man, it ain't that easy. I wish it was, but its not. Those kids don't go to church for the right reasons. It's like the fucking social hour for them. Do you really think they talk about different stuff when they're at church. No, they talk about the same kind of stuff they're talking about right now. Guess what so and so did. Guess what so and so did with so and so. That's blasphemy." "Don't get me wrong but how do you know how they act in church?" "You know April Sherril?" "Yeah I know of her," I said. April Sherril was one of the best looking girls in the school and she hung out with the snobs. "What about her?" "Well, I used to go out with her. I'm sure you never heard about it because we, kind of, kept it undercover. She didn't think her parents would approve. I finally got so sick of sneaking around. I told her that we had to tell her parents. So, she told him then her old man thought it would be a good idea if I went to church with them. So, I went and we sat with all her preppy, little friends and they all looked at me like I was shit. But anyway, do you think religion came up once in their stupid little conversations." "Well I—" "Not once," he said. "You know my dad has drug me to church by my fucking ear. If I acted up in church he would make me memorize passages from the Bible. Those kids don't understand that it's a losing battle." "So why do you even go if its a losing battle?" I asked. "Because it's the only thing you can do. At least He'll see you're trying." "You think He's up there taking roll or something?" My tone was sarcastic. I was getting angry. His comments about eternal damnation were giving me the creeps. "Why not? He's God isn't He?" "Well, all I'm saving is if I was to go to church, I would rather go there 'cause I wanted to instead of somebody making me go." "Well who are you to judge?" Johnny said. He was angry. He was looking in my eyes but I could tell he was thinking about something else. He was trying to remember something. A sly smile crept across his face and he raised his index finger to my nose. "Judge not, lest ye be judged," Johnny said. "My old man made memorize that one for screwing up." "What did you do," I asked. 1 *»'. remember."

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

The Western Carolinian is Western Carolina University's student-run newspaper. The paper was published as the Cullowhee Yodel from 1924 to 1931 before changing its name to The Western Carolinian in 1933.

-