Western Carolina University (21)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- George Masa Collection (137)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (3080)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (422)

- Horace Kephart (973)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (89)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (318)

- Picturing Appalachia (6617)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (153)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1463)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (67)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (2008)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (3032)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1945)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (195)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1680)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (556)

- Graham County (N.C.) (238)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (525)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3573)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4925)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (35)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (13)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (421)

- Madison County (N.C.) (216)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (135)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (982)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (78)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2185)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (86)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (192)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (3)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Digital Moving Image Formats (2)

- Drawings (visual Works) (185)

- Envelopes (101)

- Exhibitions (events) (1)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (823)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1045)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (6090)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Notebooks (8)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (194)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12977)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (6)

- Portraits (4568)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (181)

- Publications (documents) (2444)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Relief Prints (26)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (1)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (802)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (18)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (329)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (462)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1482)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (36)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1923)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (190)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (111)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (2012)

- Dams (108)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (63)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1198)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (47)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (122)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (9)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (72)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

Interview with Joe Rhinehart, transcript

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

Interviewee: Joe Rhinehart Interviewer: Katie Bell Date: October 11, 2014 Location: Jackson County, NC Length: 56:29 Katie Bell: All right, well, I have a few questions, but I really want to know what's most important to you. Joe Rhinehart: Are you gonna ask me questions to start with and then let me work into something else? KB: Yeah. JR: Well probably what you ask me we'll get me into other things. KB: I like to start out I know a little bit about your background from actually some from this little book that you edited, which I enjoyed a lot, but also some from of your background from Pam Meister and whatnot but for the interview, I'd like to hear where you were born. And all that background and whatnot. JR: Background I was born in Webster in 1938, August of 1938. Almost in a briar patch because my mother was picking blackberries when she started, and so we ended up getting home before I came, but not at that very time. So poor Big Doc Nichols, who just made his house across the street from us, he came out, I think at 2:30 in the morning, after pulling me out of the briar patch to be born. But I grew up there. My grandparents were there, and my great-grandparents, my great-great-grandparents for a number of generations back, about to the beginning of the county. My great-great-great, I guess, Dills, J. Ramsey Dills. KB: Okay JR: He was the brother of William Dills. He was the oldest of the Dills family, and his father Phillip Dills. Well they were involved with Dillsboro. J. Ramsey Dills had been my great, I think great three greats grandfather. He was in Webster also and the Civil War, and a prisoner in Ohio during the Civil War, but then came back here after that. And then the family moved from Haywood County when Webster was established. There were no towns in Jackson County. I don't know how much you know about the history, but we were between Macon and Haywood Counties. The Tuckasegee River was the boundary between the two. So, petitions and so on to the legislature in Raleigh they decided to form a new county, taking property from both sides, one from Macon and one from Haywood. The county seat was picked to be halfway between, it was on the river and the county seat. No towns here, a store or two in the county, but not anything such thing as a town. But they decided to put the county seat where Webster is located, and they just picked that. It's on a high hill overlooking the river this way and it would have been in the part that would have been Haywood County, but just barely, just across the river. And so that was how the county seat came to be, named for Daniel Webster, which is interesting too. The county was named for Andrew Jackson. They named it after two political parties, the Democrats and the Whigs. And of course, this was 1851, and Daniel Webster was one of the strongest abolitionists in the country at that point. Yeah. KB: That's interesting. JR: It's interesting. Yeah, because being in the South, but of course, I don't think that western North Carolina is as Southern. I consider myself more of a mountain person than I do Southern person. We're different from so many of the southern, like South Carolina and Virginia, that areas. But anyway, that was where the town was settled was to be, and they laid it out, and the courthouse was built and then it brought in people. The population of Webster never got very high, but anyway, it stayed there until 1914 when the county seat was moved here. And Sylva the next year, it was made into a town. So that moved Webster, the county from Webster to Sylva, which meant that Webster became more or less just a residential area. If you know what we've been through, right? Yeah, you know, it started to get businesses. But my grandparents had run a hotel there, and it burned. It was a big hotel. Webster had five hotels at one time. And it was where people came to because that was the only town, and it became, this whole area, a resort. Like it is today, and it started in those days with people coming up to stay and whatever. But the hotel burned in 1910, the year my father was born. KB: Where was that hotel? JR: The hotel, yeah, it was between where the courthouse was, the Buchannan Loop, and the Methodist Church. KB: Okay. JR: And it was a very big, very elegant hotel. The Firestone, Henry Ford, when they came here, stayed there. Brought the first car to Jackson County. KB: I've heard that, yeah. JR: So then my grandparents had come over from Haywood County, my great-grandparents, I guess, had a store, and my grandfather took that over. After the hotel burned, they moved to a number of places. They moved up to Canada and not Canadian Canada, but Jackson County Canada. And they operated, not a hotel, but a place where people could stay, stop on their way, say to Brevard. They could stop, spend the night there, they’d take care of their horses for the night, feed the horses, take care of them, have them for supper and all that, then they’d move on. And that was in Canada. They did that for a number of years, but they ended up coming back. And when my grandfather died, he was running his store. It was a country store at that time, gone now, but it's where the post office was. KB: Okay. JR: The road was not paved in Webster until 1951. It was a dirt road through there and sometimes almost impossible to get anywhere because in the winter it would be muddy and all that sort of thing. But it was the year 100 years after the founding of the county that they paved the road. KB: About time. [laugh] JR: Yeah, about time [laugh]. So anyway, that's what got me started, and I finished high school at Webster and then went to school, to undergraduate school at Pfeiffer, which is down in the eastern part of North Carolina, and then to Chapel Hill. Well, that didn't come until a bit later. Then I started working in Washington, D.C. teaching. I taught school for 30 years in Montgomery County, Maryland. And during that time, I got a fellowship from the Wall Street Journal to study in Oregon the University of Oregon. So I did that and then went back to Maryland and stayed there until 1986, then back to Webster. My wife and I built our house in Webster, and she was from Kentucky. And I still have that house too now, in Kentucky. But we built it, she wanted to build a house. And so she designed it, and my gosh did a good job with the hammers and saws on it too windows and all that sort of thing. KB: How did you meet? JR: We met when I was teaching in Maryland. We met in the mid-60s, and then we were married in 1968. And then we came back here in 1986. KB: What part of Kentucky was she from? JR: From Lexington, well Georgetown, north of Lexington. In fact I was there last week, and I've got to be up there this week too. I've kept the house there. She passed away in 2000. So I've kept the house and go back and forth whenever. We just had this festival today, yeah, and last week we had the horse festival up there. I’ve had festivals all over the place. KB: Oh my goodness. JR: So that's enough about me. That's enough about me, not pretty much, but that's about it, I think. KB: You just blew through all these questions, that was fantastic. But no, I wanted to ask about your work with identifying Webster as historic. JR: Well, we did two things, and I was in Washington when all this was going on. The Webster Historical Society had been formed, I think, about 1972 or '73. And so that's how we started doing things. For example, one of the first things we did was to do a Webster Cookbook, and it was written up just last month in the Southern Living. Now the cookbook, we were not certain how we could do it. It's a hardback book. It's a very attractive book, and Flossy, my wife, did the pictures for it. KB: Really? I didn’t know that. I saw the book at the mountain heritage. I was flipping through. JR: Each of the chapters is introduced by a story, and the stories tell much of the history of Webster and that sort of thing. And so we didn’t know, we worried about how we'd sell it. It did. We sold, I think, two or 3,000 for $6, thinking that was an awfully expensive price for a cookbook. Now, if there's a book available, the one across the street has a bookstore across the street from us, and has a copy of it. It's $125. So that's the, if you can find one, and people find them all over. It's funny how books move from places to places. A friend of mine found one in Victoria, Canada, in a bookstore there. And so that started, that has given us money, provided… the Association decided on two things. One would be to do a, it had been started already twice, in fact, to try to list all the places in Jackson County. And we raised about, I think it ended up being about $30,000 to bring an architect here who stayed six months and went all over Jackson County taking pictures and write ups of practically everything. That included springhouses and smokehouses and everything, as well as buildings and barns, and she photographed them, and they're all now in the archives in Raleigh. Well, maybe they're still over in Asheville. They have a branch there. KB: So, but right, yeah, actually, Jeff Futch came and talked to one of our classes. JR: If you look in there all the things on Jackson County were donated. But then we hired another architect to go through and pick out the historical buildings of Webster, and that included six at that point. There's still some others that could get in. We could, but we have six there now. The Judge Moore house is there. He was the federal judge and also the Speaker of the House of Representatives in Raleigh for a time or two. He's the one who got for Western Carolina their first grant. Which is what they're celebrating now. He and Professor Madison, I want to talk about him some too. Judge Moore and Madison worked together on that. They asked for $3,000, they ended up getting $1,500. Which made the change from just a high school to the normal school, which got it into the college level. And I think that Western Carolina was the first of the state schools to get a grant for normal like East Carolina, Appalachian and those schools started that also, but I think it started because of Western Carolina. So his house is there. Then David Hall house is there. He was a Congressman from this western part of the state. And that house down on the river, a beautiful house, is one of the early outstanding houses. Both the churches are on the National Register, the school is on the National Register. the interesting thing about the school, it was the WPA building, and it was built by rocks from the Tuckaseegee and Little Savannah Creek. They were all hauled up there. And the application says that it's one of the schools that were built about the WPA. It’s probably the most elaborate, outstanding looking school. And nothing's been changed much on the inside of it. It’s still used in fact. And let's see, there are three houses the Hall house the Moore house and Miss Lucy's house, who was an interesting character. Her father, she never married, but her father was tied in with the Vanderbilts and the logging business and all of that over in Pisgah. She started our picnics, Miss Lucy's picnic in 1946. She and her girl scout troop. Started the celebration of the Fourth of July at the end of the Second World War. And it involved a community of everybody. A big picnic at the school, a parade down the street with everybody marching, the whole town, and we’ve kept it going since then. This is the whatever ’46 to 2014 is however many years. 70 or 80 I guess. KB: That’s quite a long-lived festival. JR: Yeah, a long time to keep it going. As a matter of fact we have it still at her house, in her year. And the people who own the house through the years have always let us use it. And it’s part of the celebration is that. So her house is on it, it’s a beautifully built house. KB: Where is it? JR: Instead of going around the curve, you go just right up the hill and it’s right on the right before you start up the hill. And so those are the ones in Webster. We really made the money through that cookbook to pay for these things. KB: That’s amazing. JR: It is. So we’re thinking right now of a new edition of the cookbook, because this article that was in Southern Living last month has brought in people from all over creation. KB: I was just talking with one of my friends, wouldn't it be cool if it is new edition, so I'm glad to hear that. [laugh] JR: What we plan to do because so many of those people in that cookbook are dead now. And what we're going to do is not change that part of the book, but add a new chapter to it that will take from 1974 to the present day with all the new people who have come in and help or have another story or two in there that they have seen. So I think we'll do that. KB: Well put me down for 2 books. JR: You’ll be the first. So that's how the society, and it's kept going. And now it works with the Jackson County Society, for the museum we have is at the courthouse. Have you been up there yet? KB: Yes. JR: And it's an interesting museum because we have those two rooms which were the Registry of Deeds office, which is not a lot of space for a museum. And that limits what we can do, not with the displays, but what we don't do is have any storage room for space so we are very limited by what we can take. Therefore we have done two things, the first room is that Registry of Deeds office and from Jay Coward we've gotten desks and various things. Back in that corner exactly where a picture of Glenn Hughes sits over his desk and we put the telephone back on the table desk back and then we just leave and that sort of permanent thing. Mrs. Buchanan who founded the library, the Jackson County librarian was librarian at Western for years. Yeah, she we have her portrait there and we have Professor Madison's and we consider probably the outstanding contributor to the county through the formation of what became Western Carolina University. And that stage we also have an original map of the county, Jackson County at one time touched three states South Carolina and Georgia and Tennessee. It just went across the whole end of the state if you're going and not many people were going east west. Say from Asheville to Murphy or Franklin, you came through Jackson County, if you're going north toward Tennessee, that way you came through Jackson County. Then they took in 18 I think ‘71 They took away the northern part of the county and that became Swain County, which comes between us and Tennessee. But so what we done is keep that room pretty much a permanent display. It has, we have a new exhibit there on all the National Register properties. We now have 20, and there are pictures of them at their label. And we've been doing a series in the Sylva Harold on each of these buildings and what the building, the history of it. Starts with Judaculla Rock, which is 13,000 years, and we come down to I guess the last one was the Webster School in 1938. And we have all over the county. From the southern part of the county we have High Hampton Inn and we have Camp Merriwood, the Backus Lodge, and it goes runs on down through the county. Sylva has the courthouse and Sylva is now a national registered district, it's on the Main Street. We have a beautiful in fact picture to use with it because Jack Stern who lives up in Canada is an artist. And he painted for us in oil, looking out the window of the museum up the Main Street, which is the historic district is the Main Street of Sylva. And that's what I'm going to be talking about today when I take these people off on they're tour. Are you going to be able to go along? KB: I hope so. JR: Well you’ll learn more history that. And the thing about that tour is that I've asked a number of people to come back and talk rather than me talk about it what I just know about a building or whatever. People who use these buildings, most of these buildings are not owned by the people who originally were in them. And when Sylva 19 Let's say 1914, and none of those buildings has the same business in it that was there originally. So for example, Sylva Supply, I’ve asked Bob Hall to come home over from Asheville, his father ran home and built the Sylva Supply. So at 92 he's going to be sitting out there talking, and when we come around his building, he's going to talk a few minutes about the building because he knew it. If I did it, I’d just pass it on, and he is really involved with it. Across the street, in the bank, Tom Davis, who is also 90, his father was president of that bank when it closed during the Depression. So he's going to talk about the bank for five minutes. And Ruth Crawford is going to talk about, she lived upstairs over the Farmers Federation and she's going to talk about living up there and working at Velt's Cafe, which was very much a landmark. So, that's what we will see today, going up one side of the street and down the other, with these people who know the buildings and who were involved with them in some way, talking about that. And then I have a stack of old pictures to show, here’s how Main Street looked. You're standing here right now, looking toward the courthouse. And this is what you would have seen if you had been here in 1921, or whatever the dates are. So that's going to be at noon today. KB: At noon, okay, I’ll have to sneak down there. What got you interested in seeking out these histories of Webster and whatnot? What caught your eye? JR: I don't know why. KB: People ask me the same thing about various projects. JR: I guess for my family, for one thing. I'm involved in part of it. I've never been very interested in genealogy. We never talked about it much—who was this and who was that? My mother grew up in a house with her great-grandfather and he had been in the Civil War, and we knew back to him. That’s as far back as we went, and that's the Macon County side of us. And then in the Jackson County. I knew my grandfather, well he died when I was five years old, but I knew the background of that. But I've never really… but I did like history, American history. And being here and with the Cherokee and all those things, you just naturally, I think, were taken toward that idea. So, I really don't know why. That was never something that I knew much about. But then the people who wanted to start the historical society in Webster took me out for lunch one day. I was just here in the summertime. And she said, "Now, what are you going to do?" And so I learned to cook. We didn't have many cooks in my family. I didn't cook then, but my wife and I got back to Washington from our wedding trip, and she gave me a box with a mixing bowl, a whisk, and two cookbooks, and said, "Now, I'm not cooking anymore." And she was an excellent cook and inherited it. And I was not—I couldn't make cornbread. That was it. And so she said, "I'm not cooking anymore and I mean it" and she never did for the next 40 years. She never coked a meal. She said, "I'll take care of the kitchen, but you go to do the food." So we did—that's, I learned to cook because of necessity. And I liked it. It was what got me started in the cookbook idea, of doing that, and it's been one of the main supports of the historical society. So we may start it over again. KB: I would be really excited to see that. JR: I like to keep it as much as we can as it was. But bring it up to date with new recipes and what's changed. ’74, that’s been 40 years ago—this book is 40 years old. It's hard to believe that sort of thing, but it is. But I want to do something to talk to you about the founding of Western Carolina because I've been up there several times to things there. I’ve gone there all my life for things, I still do, but I'm always somewhat amazed at how little the students and the faculty know about that school. They don't know what went into it I don't think. When you had the celebration the other day out in the courtyard, there were hundreds of students and people. The Mountain Heritage Museum had some tours, and I went on that tour. There were a number of students on it, and some of them had never been to the old part of the campus. And of course, it's not in use very much now, so there's not a great reason to go except it's the beautiful part of the campus up on top of the hill. It just surprised me. The monument to Professor Madison is at the foot of the hill, and it's not exactly at all like what it was when it was dedicated to him. They've filled in the pond and it's even filled in with flowers now. There's no marker pointing to the monument. But I lived next door to him and I grew up as a child. He died in 1952, I think, or '53. I would have been in high school. I spent a long time with him. His first teacher he hired, or really the second actually was the music and art teacher. KB: I think we have the portrait up in the Mountain Heritage Center. JR: And the interesting thing in Webster, one of our historical things is our summer evening in Webster. We started in 1981 to commemorate. Because in those days there were dirt road and no traffic, and their house was just down the street. Miss Madison played the piano and he played the flute, and I guess the violin. They would sit on their porches on summer evenings and play, and the other neighbors close by would sit out on their porches and listen to the music on Sunday evenings. So we started a summer evening in Webster, and it's been going on since 1981. Five programs a summer and they're all—we dedicate the program to the Madisons because they really started it with their life of music. So that's one of our big things, and we made the picnic part of that too. This past year we had opera, we had Irish folk music, we had mountain music, and we often have a play or whatever. And all of it's free and we have refreshments afterward. We usually have a full house for it, but people have been coming and coming for it for a long time. So that's one thing dedicated to the Madisons. But the Madison’s, I don't know if people even know that Professor Madison’s father was from Lexington, Virginia, and his father was Robert E. Lee’s physician. He was with Robert E. Lee, his father, Dr. Madison, was with him when he passed away. And Professor Madison, one of the stories he liked to tell us was about Robert E. Lee’s horse, Traveler, dying and they had a military funeral for it and he watched it, saw it. Gary Carden has written a very good story about Professor Madison and the death of Traveler and that sort of thing. He's been good for our summer evenings with his stories of with his plays. We've done some of those. But the Madison thing he did also, because he met Professor Madison once too. But the Madison’s gave literally everything they had to that school, financially and everything. As far as I can remember, hardly any money to. Anyway, I have so much respect, and I just have the feeling that the college faculty and students need to know more about that. It's a valuable resource for us here, and it's a valuable resource for the state. My grandfather graduated from school there in 1889. KB: What was his name? JR: Jacob Parker Moore. I have a picture of that class. Interesting thing, he was in classes with three other people who became lawyers, Patton from Macon County, Sherrill from Webster, and Judge Alley. My grandfather became a teacher. They would go out to the woods, which was about all there was in 1889, and they would practice their law, trying people. My grandfather would be the judge, and he would come up with things like, "This is not going to work," or "This doesn't make the right impression." He would tell them, be the jury. But he was very much involved with Madison too, they became good friends. He didn't have the money to really go and I think it was only $17 or something. And Professor Madison would send him a bill and say, "Now, don't worry, Parker. We’ll take care of this as soon as you can." But having money was hard. I mean there wasn’t any such thing as money. But he did influence him, and I keep thinking that if it hadn’t have been for him, my grandfather would never have gone past the 8th grade, if it hadn’t been for my grandfather, my mother would never have gone to college, gotten a master's degree in Latin. If it hadn't been for her, I would probably have not. So the so many of us in this area are tied through a chain to what that school, even though I didn't go there, and my mother didn't go there. I mean we went, but we didn't graduate from there. We took classes and whatever. But the ties and what it’s done for us is just something that needs to be told. And I've worked on that with various people, I've not gotten very far. Maybe this thing will make us known, or somehow hear it that can do something about it. And so I hope that that will happen with. I knew the Madisons, and I knew what they went through with and I heard what they did. And what they did is one of the major things, institutions in this state, and it certainly took it up to national levels now. So I think that somehow there ought to be an orientation class or something, not just for the faculty, I mean for the students. But so they realize how important this is and how they could be a part of it. KB: Yeah, that's exactly what we're I graduated from in Kentucky, they had a class required. It was a writing class, but the entire thing was writing while you're learning the history of the college. Yeah, that would be really cool. JR: And it would be good to have more history of the college. We've depended on other people, maybe a professor to write it. But we need people who, well there was a book written, an early book. I don't know if you've seen it or not. Dean Bird, Bird’s book, well that was started out to be written by two people, Dean Bird, and his name is not Dean. His name is William. But he was the dean and the president. And he and Lillian Hirt, she was a teacher there too. And they started writing together. And finally, Ms. Hirt said, I’m just going to turn it all over, we right in such different styles. He wrote in a Victorian style, and she's writing in modern newspaper style. So she said, we just can't put this book together with us both. So he just took it over and did it. She backed out, but she did. She wrote a lot of the poetry and we have one of her poems on the wall of the museum. A beautiful one about we have four paintings, photographs, of Jackson County in the four seasons. And she had written this beauty. She was very tied, she was from Hazelwood, very tied to the mountains. And she wrote a poem about why she wants to go somewhere. But she can't leave in the winter because of the snow and the beauty of the ice. And all, she can't go in the spring because it’s green, she can’t do this in the summer, the fall won’t let her go, so she’ll just stay at home. She doesn't need to travel. Then a local art photographer, Scott Hotaling did the pictures for us and they're beautiful pictures to go with this poem. So anyway, there are just so many nice things that have come out of that school, and what it means to this place, Jackson County. It is certainly the largest employer in the county of nothing else. And it brings 10,000 something students to the county who live here for 10 months or whatever. And I think we need, they need to know the value of it for them as well as for us and what it meant to get the place started or one-room school to what it is now. KB: So you had mentioned an email just now about stories of Madison would tell. Do you have any more? You've got the horse one? JR: Well, the horse story, and the other story, he was also related to the President James Madison. I think he was his great, maybe two great uncles. But anyway, they are very much related. And they Madison, the president in Montpelier, Virginia, and these Madisons, he had a number of children. And they went, they go to the Madison or did go to the Madison reunion. And I know that they gave back to the family, to the Montpelier house, in Virginia, President Madison's silver service. These Madisons here had that and they gave it back to the house to go into it. So well, one of the things, I used to go down in the summer, and I'm barefoot most of the summertime, and he would be upstairs, my good friend Jack Ellison and his mother lived with him at the toward the end of his life. And Jack, he'd go up, have his dinner and go upstairs and then come back down. He was blind at the end of his life. And he would come down. A lot of times, I would be waiting, I'd sit there and put my sandy feet in his chair. And he was he was blind, but he can tell that there's sand or dirt or whatever, on his chair, and he did not like it. He also wrote many poems. And he would print these and pass them out to people or use them for Christmas cards. And that's what the book came from, the Madison book, this book that you have, this is done in Kentucky printed by a printer there. It’s done on handmade paper, hand set and hand bound, it’s a beautiful, beautiful book. We still have a few of those left. Anyway, some of these came from that. I went through the poems before they went to the library at Western and picked out. He was not, as I said in here, probably the greatest writer of poetry. But he wrote with a feeling of things. And he wrote beautifully, he had a wonderful word, vocabulary that inspired me. It seemed like he could just pull out of any conversation, if he were sitting in my grandfather's store with a group of men. And he's smoking his cigar there because Mrs. Madison wouldn’t let him smoke in the house. And he came up every day to smoke his cigar, and they’d sit there and talk. And whatever the conversation was, he could pull a quotation from somebody or something, a poem of somebody, the Declaration of Independence, whatever it was, to fit right into the conversation. And I know that was one of the things that impressed me about him. And that makes me think that we should memorize more poetry. When I was at school, we had to remember Miss Davis, the English teacher at Webster had us remembering 50 verses. We had to stand up in front and 50 lines of poetry and stand up. And I still, when I see that all the daffodils, I think “I wandered lonely as a cloud that floats on high and all the daffodils dancing” in the thing. And when I went was in England, went to Grasmere, where William Wordsworth lived. And I couldn't have another pot Daffodil blooming. And I couldn't help but say that poem. KB: When did you travel there? JR: Oh, well, I've been there three or four times. Yeah. My wife was a great anglophile. We never gotten much, our favorite places are Orkney and Shetland, way at the north of Scotland, and we've gone there a number of times, but we've been to England too. I love the lake region where Grasmere is. KB: I have not been there yet, I have been to London, but I haven’t been outside London. JR: Well when you do take the train. That’s a wonderful way to travel and to see things. But Grasmere, I am a great fan of Beatrix Potter and Peter Rabbit. Now that sounds peculiar. KB: No, no. I grew up on it too so. JR: That we did, but I came, you know, I had a great appreciation for her because she saved the Lake District by buying hundreds of acres of land and given it to the National Trust. I think next to the Queen, she owned more land than anybody because every time an acre would come up, she would buy it. In the end she turned it over to the National Trust of Great Britain. And I don't know how many farms that she has. Wonderful places to walk. And I have a great respect. I have a new little baby friend and the first thing I gave was Peter Rabbit. So anyway, I think maybe we should go back to poetry and remembering these things. And being able to in the right occasion come up with them. But Professor Madison was blind, as I said, and he was a member of the Webster Church, the Methodist Church for about 50 years. And if you go there, the seats are still in order for him. They've never been moved. He would have to come in and he would feel his way up the aisle, and then the top first seat on that side was made smaller, so that there's nothing there for him to touch cause the side and that was where he sat. He brought his dog with him and the dog came in every Sunday. And so we decided that if he could, the rest of us could. So we often had as many dogs as we had people. They went right under the benches. Everything in that building is original, nothing has been changed in it. It's just like it was when it opened in 1881, or yeah 1881, I think. And the pulpit, all t

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

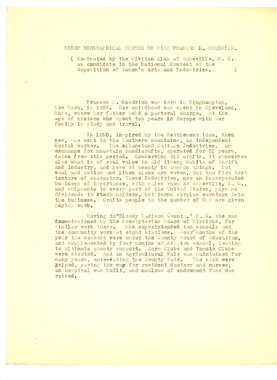

Joe Rhinehart was born in Webster, NC and shares the origin of Jackson County and more specifically about Webster including its founding, prominent families such as the Dills, McKees, Sherrills, and Madisons, and various buildings and houses that are on the national historic register. Rhinehart talks about his role with the Webster Historical Society and the cookbook that has funded it. He describes the Jackson County Genealogical Society and touches on the history of downtown Sylva, which is celebrating its 125th anniversary on the day of the interview. Rhinehart goes into detail about Professor Madison, the “outstanding contributor to the county through the formation of what became Western Carolina University.” The interview is rich with information about Jackson County and its people.

-