Western Carolina University (21)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- George Masa Collection (137)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (3080)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (422)

- Horace Kephart (998)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (89)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (318)

- Picturing Appalachia (6617)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (153)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1463)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (91)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (2008)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (3032)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1945)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (195)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1680)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (556)

- Graham County (N.C.) (238)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (535)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3573)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4925)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (35)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (13)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (421)

- Madison County (N.C.) (216)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (135)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (982)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (78)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2185)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (86)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (193)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (3)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Digital Moving Image Formats (2)

- Drawings (visual Works) (185)

- Envelopes (115)

- Exhibitions (events) (1)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (823)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1070)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (6090)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Notebooks (8)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (194)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12977)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (6)

- Portraits (4568)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (181)

- Publications (documents) (2444)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Relief Prints (26)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (1)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (802)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (18)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (329)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (462)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1482)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (36)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1923)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (190)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (111)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (2012)

- Dams (108)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (63)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1198)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (47)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (122)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (9)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (72)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (174)

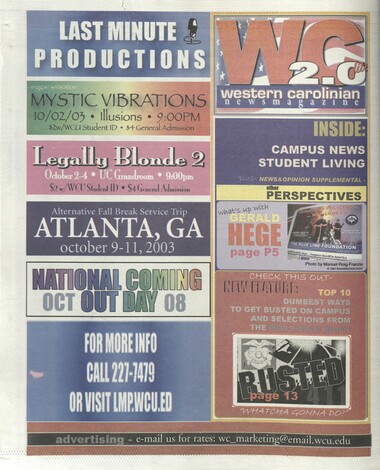

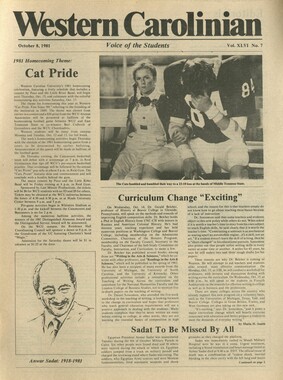

Western Carolinian Volume 68 Number 04

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

NEW MONTHLY FEATURE: SECTION USA Patriot Act: Secrecy Obscures Debate Over Anti-Terror Powers By Amy Goldstein I The Washington Post In Seattle, the public library printed 3,000 bookmarks to alert patrons that the FBI could, in the name of national security, seek permission from a secret federal court to inspect their reading and computer records—and prohibit librarians from revealing that a search had taken place. In suburban Boston, a state legislator was stunned to discover last spring that her bank had blocked a $300 wire transfer because she is married to a naturalized U.S. citizen named Nasir Khan. And in Hillsboro, Ore., Police Chief Ron Louie has ordered his officers to refuse to assist any federal terrorism investigations that his department believes violate state law or constitutional rights. As the second anniversary of the Sept. Il, 2001, attacks approaches, the Bush administration's war on terror has produced a secondary battle: fierce struggles in Congress, the courts and communities such as these over how the war on terror should be carried out. At the heart of this debate is the USA Patriot Act, the law signed by President Bush 45 days after the terror strikes that enhanced the executive branch's powers to conduct surveillance, search for money-laundering, share intelligence with criminal prosecutors and charge suspected terrorists with crimes. Yet the paradox of this debate is that it is playing out in a near-total information vacuum: By its very terms, the Patriot Act hides information about how its most contentious aspects are used, allowing investigations to be authorized and conducted under greater secrecy. As a result, critics ranging from the liberal American Civil Liberties Union to the conservative Eagle Forum complain that the law is violating people's rights but acknowledge that they cannot cite specific instances of abuse. "The problem is, we don't know how (the law) has been used," said David Cole, a Georgetown University law professor who has represented terror suspects in cases in which the government has employed secret evidence. "They set it up in such a way ... (that) it's very hard to judge." Attorney General John Ashcroft and other supporters of the law assert that the act is crucial to allowing the government to fulfill its anti-terror responsibilities, but they say little about how it accomplishes those tasks. Justice officials praise their newfound ability to share information from foreign intelligence operations with criminal investigators, allowing them to more swiftly disrupt potential terrorist acts before they occur. Ashcroft says that the law has not gone far enough, while an unlikely alliance on the ideological left and the right insists that it has trampled civil liberties and must be curtailed. This summer, two major lawsuits were filed challenging the Patriot Act's central provisions. The Republican-led House startled the administration in July by voting to halt funding for a part of the law that allows more delays in notifying people about searches of their records or belongings. And the GOP chairmen of the two congressional committees that oversee the Justice Department have warned Ashcroft that they will resist any effort, for now, to strengthen the law. Viet Dinh, a former assistant attorney general who drafted much of the law, said the debate over its merits is constructive. He said the government is gravitating now from "the sprint stage" to the "marathon phase" of confronting terrorism "Somewhere in this marketplace of ideas, of truths and half-truths, of fact and spin, we get a picture of what the (Justice) Department should be doing," Dinh said. "The debate is healthy to establish the rules of this continuing path toward safety." Exasperated with how little they knew about the ways the Patriot Act was being applied, the ACLU and the Washington-based Electronic Privacy Information Center went to court last October with a freedom of information complaint against the Justice Department. Before a judge dismissed the case in May, Justice officials released a few hundred pages that said little about their activities. One document was a six-page list of instances in which "national security letters" had been issued to authorize searches—with every line blacked out. Last year, the House and Senate Judiciary committees—charged with overseeing the Justice Department—began to send the agency written requests for statistics summarizing how often Patriot Act provisions had been used. The first replies largely made clear that the information sought by lawmakers was classified. In such a climate of official secrecy, there are nevertheless small clues to the extent the law is helping authorities' anti-terror work. In May, the Justice Department told Congress that it had asked courts for permission to delay notifying people of 47 searches and 15 seizures of their belongings. The document said the courts had consented every time but one, but it did not detail why the delays were needed. The next month, in testimony before the House Judiciary Committee, Ashcroft said he personally authorized 170 emergency orders to conduct surveillance, allowing investigators 72 hours before they must seek permission from an obscure, secret court whose role has been expanded under the law. Created a quarter-century ago under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), the special court requires a lower burden of proof than criminal courts do when authorizing wiretaps and other forms of surveillance. Before Sept. 11, 2001, its primary focus was foreign intelligence cases. Under the Patriot Act, investigators can go before the court in cases that are primarily criminal as long as they have some foreign intelligence aspect. Ashcroft told the committee that those 170 emergency FISA orders represented three times as many as had ever been authorized before Sept. I I, 2001—but he did not disclose how many or them ihad involyecL terrorism cases. Nor has the department said how often it has used FISA court orders to search libraries, the realm that has provoked perhaps the strongest negative reaction. The Justice Department's interest in libraries revolves around their public computers, over which potential terrorists could communicate without detection. One source familiar with the department's activity said that FBI agents had contacted libraries about 50 times in the past two years, but usually at the request of librarians and as part of ordinary criminal investigations unrelated to terrorism. As for how many times the government has used the law's powers to enter a library, a senior Justice official said, "Whether it is one or 100 or zero, it is classified." As their main examples of the law's usefulness, Justice officials cite a few high- profile cases, some involving suspected terrorism. Perhaps foremost among these cases, agency officials say, is that of a former computer engineering professor in Florida, Sami Al- Arian, who was charged in February in a 50-count indictment with conspiring to commit murder by helping Palestinian suicide bombers in Israel. Ashcroft has said the indictment was possible only because the Patriot Act allows information gathered in classified national security investigations to be shared with criminal prosecutors. Actions taken under the Patriot Act do not include designating individuals as enemy combatants, which is a constitutional power granted to the president during wartime. Massachusetts state Rep. Kay Khan (D) learned about the use of the Patriot Act in her case after repeatedly asking why a $300 wire transfer had not reached her brother. She discovered that her husband's name was on a special list at their bank because it may have been used by someone else as an alias. "So we are on some list, which is scary," she said. "I just feel that it's intrusive." Critics of the law complain that cases such as Khan's are of greater concern than investigations, such as Al-Arian's, that lead to prosecutions. "We are more concerned about the information that is collected and maintained on potentially thousands of law-abiding citizens who are never going to be charged," said David Sobel, general counsel for the Electronic Privacy Information Center. As the law and the controversy around it near their second anniversary, it remains uncertain whether Congress will change the law —or how strenuously Ashcroft will insist that it be strengthened. "There are no plans at this time to introduce legislation," said Barbara Comstock, a Justice Department spokeswoman. Yet a source familiar with the department's work said Ashcroft's aides have been drafting three proposed expansions of Justice Department authority. They would like to make it easier to charge someone with material support for terrorism, to issue subpoenas without court approval and to hold people charged with terrorism prior to trial. In the same vein, the Senate Judiciary Committee has been working on a bill, largely devoted to fighting drug trafficking, that in some drafts contains a few extra powers that Justice wants. Committee aides said they are unsure whether the chairman, Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, will introduce the bill. There are signs that lawmakers may not be in a mood to expand federal law enforcement powers. Last spring, Hatch tried and failed to make permanent several parts of the Patriot Act concerning surveillance that are set to expire in two years. House Judiciary Committee Chairman James Sensenbrenner, R-Wis., said, "The burden is on the Justice Department to show they are using their authorities in a lawful, constitutional and prudent manner." Sensenbrenner said he and Hatch deterred an effort by Ashcroft last winter to circulate a sequel to the law, known as Patriot Il. Sensenbrenner said that Justice officials had begun scheduling meetings with the committees' staffs to discuss such a possibility. "Both Senator Hatch and I told the attorney general in no uncertain terms that would be extremely counterproductive," Sensenbrenner said. "It would still be counterproductive." In recent months, most legislative efforts have focused mainly on attempts to restrict the law's scope. Bills in both chambers would, for example, exempt libraries from searches. The most stern rebuke to the administration came in July, when the House voted to cut off money for searches in which the notification is delayed. The sponsor was conservative Rep. C.L. "Butch" Otter (Idaho), and his amendment was supported by Ill fellow Republicans who had voted for the original law in 2001. The Senate is unlikely to follow suit. Justice officials disagree with those who say the original law was passed in anxiety and haste immediately after the nation's worst terrorist attacks. "It's a myth ... that everyone was rushing in and all had bad hair days and didn't know what they were doing," said Comstock, the Justice spokeswoman. Approval of the delayed notification provision had been bipartisan, she noted. Still, there are signs the department is worried about preserving its ground. Three days after Otter's amendment passed, an assistant attorney general sent the House an eight- page broadside protesting the vote and an addendum that derided it as a "terrorist tip-off amendment." Ashcroft last month launched a cross-country tour to campaign for the law. 0 2003 WASHINGTON POST

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

The Western Carolinian is Western Carolina University's student-run newspaper. The paper was published as the Cullowhee Yodel from 1924 to 1931 before changing its name to The Western Carolinian in 1933.

-