Western Carolina University (21)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- George Masa Collection (137)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (3080)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (422)

- Horace Kephart (973)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (89)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (318)

- Picturing Appalachia (6617)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (153)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1463)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (67)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (2008)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (3032)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1945)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (195)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1680)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (556)

- Graham County (N.C.) (238)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (525)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3573)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4925)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (35)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (13)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (421)

- Madison County (N.C.) (216)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (135)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (982)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (78)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2185)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (86)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (192)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (3)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Digital Moving Image Formats (2)

- Drawings (visual Works) (185)

- Envelopes (101)

- Exhibitions (events) (1)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (823)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1045)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (6090)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Notebooks (8)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (194)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12977)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (6)

- Portraits (4568)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (181)

- Publications (documents) (2444)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Relief Prints (26)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (1)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (802)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (18)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (329)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (462)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1482)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (36)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1923)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (190)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (111)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (2012)

- Dams (108)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (63)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1198)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (47)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (122)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (9)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (72)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

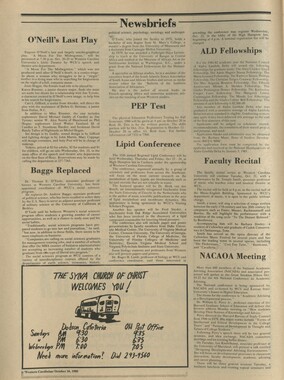

Western Carolinian Volume 67 Number 17

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

ew Security Measures' Orwellian Echoes Should Create an Outcry By Jonathan Turley Turley is a professor of constitutional law at George Washington University. In George Orwell's book "1984," the government used "doublespeak" to change the meaning of words to make the horrific appear commonplace. Thus the war department was called the Ministry of Love, and citizens were instructed that "slavery is freedom." Long thought dead, it now appears that Orwell is busy at work in the darkest recesses of the Bush administration and its new Information Awareness Office. It is a title that is truly a masterpiece of doublespeak. After all, who could be against greater awareness of information? What was not known until last week was what information the administration is seeking and how it wants to acquire it. With no public notice or debate, the administration has been working on the creation of the world's largest computer system and database, one with the ability to track every credit card purchase, travel reservation, medical treatment and common transaction by every citizen in the United States. It has been the dream of every petty despot in history: the ability to track citizens in real time and to reconstruct their associations and interests. Welcome to the latest product from the good people at DARPA. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency has been working on this project, and the pending homeland security bill would lay the foundation for the system. In a little-discussed provision, the bill combines huge government databases into a single massive system. It further weakens protections under the Privacy Act of 1974, opening the door for DARPA to develop a prototype system. With a requested $200 million down payment, the "Total Information Awareness" system could allow the government to study the purchases and activities of citizens to isolate people for further investigation, feeding names into the new massive surveillance system constructed after Sept. 11. This project is the brainchild of a man who hardly needs a new technological boost into infamy: retired Vice Adm. and former National Security Advisor John M. Poindexter. Poindexter's previous noteworthy public service was as the master architect behind the Iran-Contra scandal, the criminal conspiracy to sell arms to a terrorist nation, Iran, in order to surreptitiously fund an unlawful clandestine project in Nicaragua. Along with various other Reagan administration officials, Poindexter was convicted of five felony counts of lying to Congress, destroying documents and obstructing Congress in its investigation. He was sentenced to jail but was saved on a technicality: a poorly crafted immunity grant by Congress that required some evidence to be suppressed. One would think that a convicted felon who escaped by a technicality hardly would be welcome in the Bush administration. Yet when asked about Poindexter's prior criminal conduct, President Bush released a statement that he believed "Adm. Poindexter has served our nation very well." In some ways, Poindexter is the perfect Orwellian figure for the perfect Orwellian project. As a man convicted of falsifying and destroying information, he will now be put in charge of gathering information on every citizen, To add insult to injury, the citizens will fund the very system that will reduce their lives to a transparent fishbowl. What is most astonishing is the utter lack of public debate over this project. Over the past year, the public has yielded large tracts of constitutional territory that had been jealously guarded for generations. Now we face the ultimate act of acquiescence in the face of government demands. For more than 200 years, our liberties have been protected primarily by practical barriers rather than constitutional barriers to government abuse. Because of the sheer size of the nation and its population, the government could not practically abuse a great number of citizens at any given time. In the past decade, however, these practical barriers have fallen to technology. This new, untapped power has been an irresistible temptation for many such as Poindexter, who has reportedly been working on such ideas for years. Soon after Sept. 1 1, he appeared at the door of the administration like a J. Edgar Hoover vacuum salesman, promising a system that could digest huge amounts of information and produce neatly packaged leads on suspected citizens. A government's desire for "Total Information Awareness" of its citizens is nothing new. Our founders understood that the quality of government is determined not by the powers given but by those denied to it. A free society cannot be maintained under the continual surveillance of its governmenL&Ä.—..... the rest. '2Ö(j2 dec. 4, 2002 rt%THE COST OFWAF Special Federal Court Takes Away the Fourth By David Cole The Fourth Amendment requires probable cause of a crime before a phone can be tapped or a home searched. On Monday, a special federal appellate court, meeting for the first time in its 24-year history, ruled that the government may conduct secret wiretaps and secret searches of U.S. citizens without probable cause of criminal activity. The special court decided that, under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), law enforcement officials need not comply with that constitutional requirement, even where their primary purpose is criminal law enforcement. No one doubts the critical importance of foreign intelligence gathering as we struggle to prevent the next terrorist attack. But the appellate court's bottom line denies to all of us the Fourth Amendment's most important protection—the guarantee that our privacy is protected from official intrusion absent probable cause of criminal activity. And the process by which the decision was reached is emblematic of an even deeper problem posed not only by the ruling but by the Bush administration's war on terrorism more generally: an inordinate reliance on secrecy. 7, 2003 Cole, a professor at Georgetown University Law Center, is co-author of "Terrorism and 'the Constitution: Sacrificing Civil Liberty in the Name of National Security. " l. FISA was enacted in 1978 to authorize "foreign intelligence" wiretaps and searches. Where the amendment normally requires probable cause of a crime, FISA does not. The rationale was that wiretaps and searches for foreign intelligence gathering ought not be limited by the Fourth Amendment standards generally applicable to criminal law enforcement. But that premise is questionable. In 1972, the Supreme Court rejected a similar argument about warrantless "domestic-security" wiretaps, holding that they must satisfy traditional Fourth Amendment warrant and probable-cause requirements. The court left open the question of foreign intelligence gathering. But privacy is privacy, and the amendment acknowledges no exception. To be sure, the Supreme Court has recognized other exceptions to the warrant and probable cause requirements. The appellate court likened a "foreign intelligence" search to drunken-driving checkpoints, which have been upheld on the ground that they serve " pecial interests" (highway safety) above and beyond criminal law enforcement, impose o minimal intrusions and apply to all drivers on the road. Fighting foreign espionage and i ernationaL terrorism are certainly "special interests." But no search is more intrusive th?p- wiretap or a search of one's home, and FISA searches are targeted at the attorney gener s discretion. The deeper problem with FISA, and with the war on terrori generally, is its excessive secrecy. Ordinarily, government officials know that their tions will eventually have} to withstand judicial review through an adversarial process. FIS , by contrast, creates an entirely one-sided and closed-door process, in which gover ent actions are virtually never subjected to public scrutiny. In most instances, the targe never informed that he was searched or tapped at all. Where the government seeks use the information in a particular case, it must notify the individual that he was subject d to a FISA search, but the law makes it impossible to test the legality of the search effectively because the defendant is not given access to the application for the search. The FISA court has reportedly never turned down an application for electronic surveillance. The reason the appeals court was never convened before now was that only the government can appeal, and the government had never before lost. And Monday's decision means that it is likely to be another quarter-century at least before the government loses a FISA case again. The problem is that when officials know that their conduct cannot be effectively tested, they will be tempted to cut corners and to abuse their powers. A lower court's decision had noted that the FBI had misrepresented facts to the court on at least 75 occasions. The appellate court relegated that fact to a footnote. There is undoubtedly a role for secrecy in protecting the nation from terrorism. But, as we learned in the Watergate era, secrecy is all too often invoked not to proteCt national security from attack, but to shield government officials from embarrassing disclosures. 0 2002 Distributed by the Los Angeles Times-Washington Post News Services•

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

The Western Carolinian is Western Carolina University's student-run newspaper. The paper was published as the Cullowhee Yodel from 1924 to 1931 before changing its name to The Western Carolinian in 1933.

-