Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2946)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6873)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1463)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (2008)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2569)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1923)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (195)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1672)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (236)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (519)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3569)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4912)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (35)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (13)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (215)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (982)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2182)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (86)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (3)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (185)

- Envelopes (73)

- Exhibitions (events) (1)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (815)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (6090)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Notebooks (8)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (5)

- Portraits (4568)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (181)

- Publications (documents) (2443)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Relief Prints (26)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (1)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (18)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (462)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1482)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1923)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (189)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (111)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (2012)

- Dams (107)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1184)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (45)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (119)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (72)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

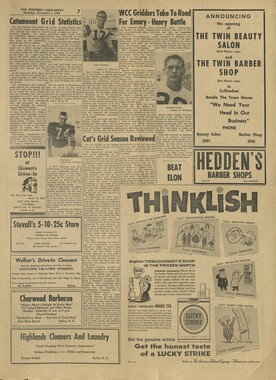

Western Carolinian Volume 44 Number 32

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

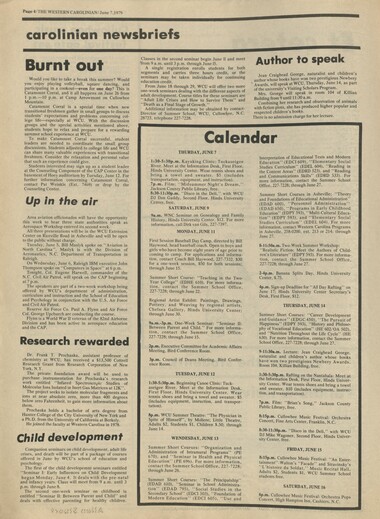

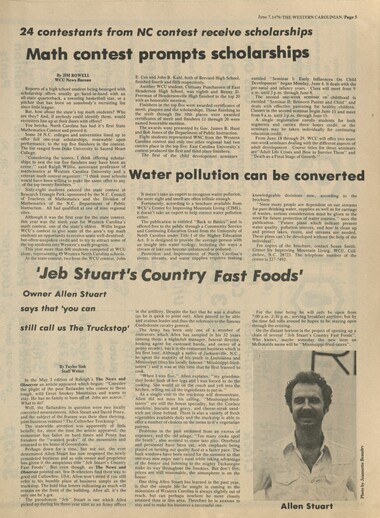

The^stern Carolinian The Voice of the Students 12 PAGES THURSDAY JUNE 7, 1979 Vol. XLIV. No. 32 CULLOWHEE, N C Cable TV could be in Cullowhee's future By Lane Gardner Staff Writer Cable TV in Cullowhee is gradually becoming more than just a possibility. Mr. William Christy of Sylva, who has franchise rights for Jackson County, is now waiting on his funding to come through before beginning construction of facilities. "I had a little problem getting my money arranged due to the high interest rate. I was trying to hedge that, but it looks like there's no getting around it. From all indications, maybe I can get started within the next 30 to 60 days," explained Christy. Christy, who has been working on this project for the past year, sys, "It's been a long, hard struggle. Many things have had to be considered.'' Pole attachment agreements had to be worked out with the telephone and power companies. Also, a site had to be pinpointed for location of the headend station. Enrollment is up . Christy says he now has two locations which are suitable for a headend station. One is at Locust Creek and the other is on Carter Top at Dick's Creek. If the headend station is built on Carter Top, Christy says he will serve Cherokee in addition to Jackson County. Christy has been working closely with Cherokee and STI. He says both are interested in originating programming. According to Christy, Cherokee has already made an application for a grant for studio equipment and for assistance in purchasing necessary amplifiers. Also, STI has already purchased a camera. Concerning WCU, Christy says Chancellor H.F. Robinson is very interested in bringing cable service to Turn to Page 3, Please Believe it or not It's quiet around Cullowhee and one could hardly tell enrollment was up over last summer. But it is and a full 3.9 percent. Enrollment for both sessions of summer school is 2,171 students taking a combined total of 14,479 credit hours. Of these students, 1470 are undergraduates and 701 are graduate students. Last year 2,089 students took courses totaling 14,261 credit hours.Besides the 3.9 percent increase in students, the summer school offices also noted the 1.53 percent increase in credit hours. Of the students enrolled in summer school classes, 701 are taking WCU classes at UNC-Asheville. There Woodstock are also students enrolled in WCU classes in other North Carolina cities which are not reflected in the figures. These figures may still increase as incoming students register for the second session of summer school. Students who have already registered for second session are included in the above totals. Besides regular students taking courses at WCU, the school will host a number of camps, both athletic and educationally oriented, as well as various other activities in the weeks to come this summer. So, by the time the second session of summer school rolls around, WCU might not be such a quiet place. Munch out! (ATTENTION ALL STAFF MEMBERS! The Wester Carolinian is having a meeting Monday night at 7 p.m'.l The only justification for missing is if there is a death in| the family-YOURS. The names are the same -only the characters have changed by MALCOLM N. CARTER Associated Press Writer WHITE LAKE, N.Y. (AP)— Although it was music that drew hundreds of thousands of young people to this Catskills hamlet on a steamy August weekend in 1969, they also came to the Woodstock festival to celebrate the spirit of social revolution. But no revolution came. . The Woodstock generation grew up and became the establishment it so opposed, its dream of creating an alternative society now gone. Like generations before, members of the Woodstock nation have taken up traditional lives. Thanks to women's liberation, more work than in previous ages. And, says the National Association of Home Builders, they bought a "starting" half million houses last vear. It was always a generation of contradictions-of flower children who opposed the war and "hardhats" who waged it-and differences remain among its members, now in their late 20s and 30s. Most of the Woodstock gene ration settled in-working, buying, rearing families like almost everyone else. But remnants of their ideals endure. They have translated the old slogans of peace and love into a greater desire to serve humanity and to fulfill themselves as well--increasingly at the expense of marriage and children. Moreover, business executives note a new skepticism among employees and a reduced willingness to sacrifice everything for the job. Along with a continued wish to "do your own thing", the Woodstock generation has left as its legacy a more relaxed view of sex and drugs. But when lots of people took to wearing bell-bottom jeans and smoking marijuana, these symbols of a generations protest lost their impact as political statements. "The trappings have given way to a search of real fundamental meanings of existence," says Peter Coyote, who went straight "when the revolution failed to materialize." A member of the "diggers," a group which sprang up to look after the hippies in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury, he is now the chairman of the California Arts Council. IT WAS opposition to the Vietnam war that galvanized his generation, and once the danger of the draft was gone, so was the urgency for activism. And as the economic boom of the 1960s ended, the Woodstock nation became more concerned about self-preservation. "They have joined the establishment in the sense that you probably will not be able to find distinguishing characteristics for them." says University of Michigan political scientist Arthur Miller, adding that the group does not seem "sharply different" from any others. But they never truly were, according to many social scientists. Most were white and middle- class, notes Cornell sociology professor Glen H. Elder Jr. Despite the talk of a "generation gap," he adds, the '60s youth and their parents were not really so far apart. "The differences tended to be just in how each generation perceived each other," Elder says. Studying 100 suburban high school boys for 10 years starting in 1962, the Universitv of Chicago's Dr. Daniel Offer reached similar findings. Surprisingly, he says, the students were the same as their parents in sexual behavior and attitude, and they were no more idealistic. When the Woodstock nation massed on the late Max Yas- gur's vast and muddy dairy pasture to hear such flawed idols as Janis Joplin and Jimmy Hendrix in 1969, it was the Age of Aquarius. "What Woodstock meant that was really unique was that we were all part of one community," sociologist Richard Flacks recollects. But the new age already was waning. When a youth was killed at the Altamont music festival in California later that year, it was a last gasp. Too, by the end of 1970, a near decade of plenty was ending as the country slipped toward a recession. The Woodstock nation stumbled into adulthood, its dream colliding with new economic realitied. According to Alvin Toffler, author of "Future Shock", all the Woodstock nation did was take up old arguments against the industrial revolution. It glorified a "mythical past" in which people lived off the land, their wits and their skills, says Toffler. Sociologist Vern Bengtsson of the University of Southern California adds that sheer mass-the "baby boom" came of age then- helps explain the generation's optimistic belief it could change the world. In his study of 2,000 individuals from three generations of families, Bengtsson found that the youth movement had altered Turn to Page 9, Please.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

The Western Carolinian is Western Carolina University's student-run newspaper. The paper was published as the Cullowhee Yodel from 1924 to 1931 before changing its name to The Western Carolinian in 1933.

-