Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (24)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- 1700s (1)

- 1860s (1)

- 1890s (1)

- 1900s (2)

- 1920s (2)

- 1930s (5)

- 1940s (12)

- 1950s (19)

- 1960s (35)

- 1970s (31)

- 1980s (16)

- 1990s (10)

- 2000s (20)

- 2010s (24)

- 2020s (4)

- 1600s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 1910s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (15)

- Asheville (N.C.) (11)

- Avery County (N.C.) (1)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (55)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (17)

- Clay County (N.C.) (2)

- Graham County (N.C.) (15)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (40)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (5)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (131)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (1)

- Macon County (N.C.) (17)

- Madison County (N.C.) (4)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (1)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (5)

- Polk County (N.C.) (3)

- Qualla Boundary (6)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (1)

- Swain County (N.C.) (30)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (1)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (3)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Interviews (314)

- Manuscripts (documents) (3)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (4)

- Sound Recordings (308)

- Transcripts (216)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newsletters (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Publications (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- African Americans (97)

- Artisans (5)

- Cherokee pottery (1)

- Cherokee women (1)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (4)

- Education (3)

- Floods (13)

- Folk music (3)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Hunting (1)

- Mines and mineral resources (2)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (2)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (2)

- Storytelling (3)

- World War, 1939-1945 (3)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Sound (308)

- StillImage (4)

- Text (219)

- MovingImage (0)

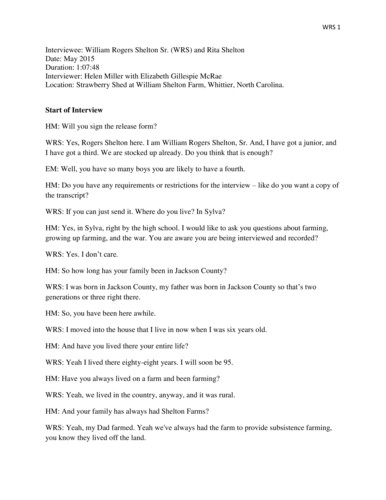

Interview with William Rogers Shelton Sr. and Rita Shelton

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

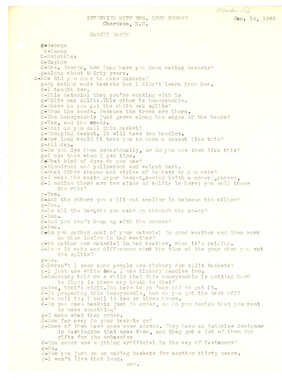

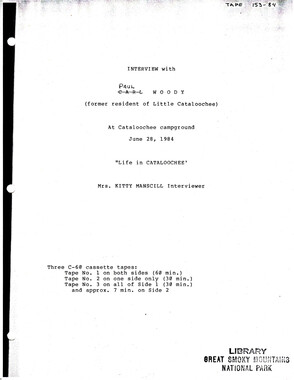

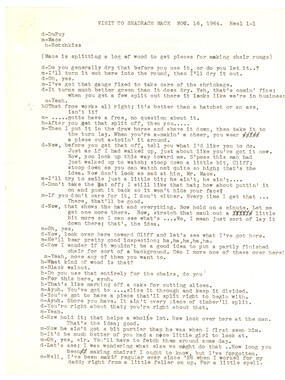

WRS 1 Interviewee: William Rogers Shelton Sr. (WRS) and Rita Shelton Date: May 2015 Duration: 1:07:48 Interviewer: Helen Miller with Elizabeth Gillespie McRae Location: Strawberry Shed at William Shelton Farm, Whittier, North Carolina. Start of Interview HM: Will you sign the release form? WRS: Yes, Rogers Shelton here. I am William Rogers Shelton, Sr. And, I have got a junior, and I have got a third. We are stocked up already. Do you think that is enough? EM: Well, you have so many boys you are likely to have a fourth. HM: Do you have any requirements or restrictions for the interview – like do you want a copy of the transcript? WRS: If you can just send it. Where do you live? In Sylva? HM: Yes, in Sylva, right by the high school. I would like to ask you questions about farming, growing up farming, and the war. You are aware you are being interviewed and recorded? WRS: Yes. I don’t care. HM: So how long has your family been in Jackson County? WRS: I was born in Jackson County, my father was born in Jackson County so that’s two generations or three right there. HM: So, you have been here awhile. WRS: I moved into the house that I live in now when I was six years old. HM: And have you lived there your entire life? WRS: Yeah I lived there eighty-eight years. I will soon be 95. HM: Have you always lived on a farm and been farming? WRS: Yeah, we lived in the country, anyway, and it was rural. HM: And your family has always had Shelton Farms? WRS: Yeah, my Dad farmed. Yeah we've always had the farm to provide subsistence farming, you know they lived off the land. WRS 2 HM: What was it like to grow up here? WRS: Well I thought it was wonderful. I had it made. And I'm still enjoying it. But it was a hard way to make a livelihood, but what really happened to us in this area was that it was so rural and nothing to do. But before that see the lumber industry and then the Park came in 1936 or something and dedicated the Smoky Mountain National Park and that gave a lot of employment. And then we had the war come along and that’s what really got everything going. People had to get out of the area if they wanted to have a job and make money. Most everybody did make a living from the land. So it was…but now instead of, this might sound a little foolish, but used to be if you courted the girl down the road and she said yeah, let’s get married you'd just got in the old T-model and drove down the road to Clayton, Georgia, and bought you a dollar and a half license and got married and come back by the saw mill and bought you a house pattern and come back home and built you a shack and started in business. But now these kids come, you know, and instead of starting there, they want a furnished house. But it’s been great to live in this area, and I've seen it grow from really rural to what it is now. It’s still rural, but there's so much activity here. And I think the farmers that are left are doing pretty good don't you think Mama? Rita? Rita: I think you might be telling that girl a tale. I want to tell you something, he used to be in the Dairy Queen business really and farming too. WRS: Oh I forgot about that, I was in the Dairy Queen. Rita: He was getting to be an older man, and I worked for the ASCS [Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service], I worked for the Department of Agriculture also and I had a Farm Bureau meeting one night. And he was the president of the Farm Bureau, and so I went to that meeting I guess I was supposed to, you know. I don't know. During that meeting he looked over at me, and he smiled. Now, he had known me for a long time, but he hadn't seen me really. He didn't look at me like that. When the meeting was over he said to me, you need a ride home I'll take you home. I said I have a ride home, and he said well I'm going right by there if you want a ride I'll take you. And I thought well okay. But now here is the catch, he lived here over Whittier, and I lived way over on the other end of the county off Tatham’s Creek on Savannah, and he said to me I'm going to drive right by there. WRS: I can add to that story. She lived across the creek on Tatham Creek, and I don't remember how long it took me to get across that bridge. I'll never forget it. Visitor: Did you have a wedding? Rita: It wasn’t a big wedding, but we had a wedding in the church. WRS 3 Visitor: Wasn’t a shotgun wedding or nothing like that? Rita: Oh, gracious no. Rita: It weren't no shotgun wedding or anything like that. No, he didn't take me to Clayton either, I wouldn't have gone. HM: What sort of changes have you noticed over time as the area has grown? WRS: Changes? Well the mostly is the traffic and the roads. When I was growing up we lived on a rural road, and there was no pavement. I don't believe it was gravel for a while. But anyway our first road was paved was graveled with creek gravel that we got it out of the creek and put it on the road and then they crushed it right there on that side and put it up. But then when the park started, they started improving the roads. And the roads that the ox wagons used to come to town on are a five lane now and you can't move. With the ox wagon, we just had a gap, and the gap is just wire with a post, the wire was wrapped around the post to keep the gate closed to keep the cattle in. But in 1936, I guess it was, we my mother hung out with a little shingle over there and we started a we call it a bed and board now, but back then we called it a boarding house. And we set up and we looked after travelers for thirty five years. And we fed them from the farm. You know we had chickens, we had hogs. We had milk cows and a garden. And we built--we had a kitchen and dining room separate from the house that we fed people in. People would come to, school was out all summer so that was our—they would stay all summer. And so that was our agricultural part. We would sell the products, but… (Inaudible, cross talk) But there was a high school. At one time there were 44 schools in Jackson County when I was starting school. Since then, it has taken down, down, down until they just have about 4 or 5 schools, now. But there was no way to get to school unless you walked. They did finally put on a bus when they could afford one. The agricultural part of it--you just lived off the land. That was the main story. You had a garden. You had a cow, you had hogs and chickens. [inaudible] The first place that we bought, where I live now there were 60 acres and we had sheep. By the time we got a tractor and we found out that when we got the tractor, we got modern… HM: I don't know much about agriculture so you’re going to have to help me here. WRS: This farm…we've been on this farm since my granddaddy came here. [inaudible]. But what we used to do, we used to grow tobacco. We grew cash crops. WRS: (to friends)You leaving? WRS 4 WRS: We had the awfulest rain here day before yesterday, you ever saw. WRS: I didn't know I was going to do this, and I am not organized to do anything but off the top of my head. HM: That is what we want. WRS: You girls move in closer to us here so we can all just get together and have a bull session. And it would amount to progress in agriculture in Jackson County over the last ninety years. That is how long I have been involved. But my dad-- he and grandpa did part of their lives, they helped build these first roads that came through. That was old Number 10 over there. They built that with horses and mules and slip pins and wheelers and plows. They built the road going into the park over there, and they built the road from Cashiers to Rosman way back. And, I, we, lived in Cashiers when I was six years old. You know I tried to figure out, they were building those roads but there were no cars in the 20s. But anyway they built those country roads that are five lanes now--progress. My dad he always had cattle and hogs and farmed and some of it he did sharecropping at the Ferguson farms. And then we bought the Ferguson its over at Chi (the?) Gateway. We bought that from the Fergusons. They had come here from Haywood County and they were, well some of them were my dad's double first cousins. That hits pretty close. The Sheltons, and the Conleys, and the Sheltons married the Conleys, and the Conleys married Sheltons and they got all mixed up double first cousins. ‘Til I met the love of my life, she's sitting over there. EGM: Are you a Conley? Rita: No, I’m related to-- his mother was a Rogers-- and I’m related to him through the Rogers. It’s about way back. WRS: We had the same grandpa five or six generations. Rita: We came from the Hugh-Rogers that was in the Revolutionary War. And the John Rogers he was way back our ancestors that got murdered at the stake in England for leaving the English church. You remember him in history? He is our ancestor. WRS: How many of those Rogers were there, twelve boys or nine boys? Rita: Twelve, I understand, but she’s not interested in that stuff. You could speak a little louder so she can hear you on the tape. WRS: Here comes the modern farmer, you see him right there. That is Will. That is William Rogers, the 3rd. I got an invite to his graduation and it said on the return: William Rogers Shelton, 3rd. Rita: I guess, she wants to know about the changes. WRS 5 HM: So I don’t know much about farming or agriculture. WRS: Well you love to eat don’t you? HM: Yes, sir. WRS: You see that sign there, Get Fresh, Buy Local, Shelton Family Farms. This has been a farm a long time, and really I’ve grown up with the progress in agriculture. Rita: This is the 4th generation on this farm. WRS: Because when I started in back there the experiment stations were just starting in, and I’ve been involved in all these experiments that have been carried on in different crops, from tobacco. We done a lot of research on tobacco and weed control, insects, and suckers all kinds of whatever happens to tobacco, that’s the reason we got these [barns/buildings]. We could house about ten thousand sticks of tobacco, and a stick of tobacco has got five or six stalks on it. And you air cure it and it hangs in the barn. And then you pull it off that stalk, and we changed the system on marketing tobacco. It had been, they had been marketing tobacco seventy-eight years, and we decided that there might be a better way so we made a change after seventy eight years. HM: And what did you change? WRS: The method. What we did at that experiment. After we got the stuff cured, we did the grading and it used to [be] all the tobacco was hand tied, you know. But we did a study on the hand tied and then we sheeted some of it-- just put it loose into these sheets, and then we baled some of it. And the bales finally took over. That’s how they sell burley now is in the bale, and the first bale was baled right here on this farm and that takes a lot of work out of it, makes it easier to handle. And in the tobacco that used to be THE crop that fed the family. That was your only cash. Rita worked with the ASCS, and they did all of the book keeping work on that, keeping up with that tobacco. So, every farm had an allotment and we all had…it was a competitive thing, every farmer was trying to get a little more, a little more, a little more. But now that is gone. WRS: Is she not going to work today, Mama? Rita: I guess not. WRS,3rd: There is really not anything for us to do. He said. WRS: Are you not working today, Will? Will Shelton, 3rd. There is not really anything to do. It is lightening out in the field, and it is about to storm. WRS: Did she go home? WRS 6 WRS, 3rd: The only thing we had to do was to move out a little bit of water, and it is about to storm. WRS: You got rid of all the water? Both ends? Up there? Down there? Center? WRS, 3rd: Mhmm. WRS: You have done better than anyone has ever done. Thank you. Do you know Will? EGM: I’ve seen him at the Farmers Market. Or used to. WRS: He is a freshman at Wofford. He’s helping us on the farm this summer.There is this girl. She is a junior at Appalachian. WRS, 3rd: Yeah, she is. WRS: She wanted to work on the farm this summer. So, she does the whole works. Whatever there is to do—ditching, or pruning or planting, or anything? You all are in the planting of the beans, aren’t you Will? HM: So your farms earn a lot over time? Rita: To get back to his farming. He had a mule and a cultivator. WRS: And yesterday, I was thinking. And I was thinking about this people all getting out of….see that right there [sound of large tractor is close] is taking the place of the mules. It’s got a cab, see they have cabs and they don’t even get wet if it rains. And they’ve got a radio and music. Rita: He went a bought a mule a few years back, just to have a mule. We named it sweet old boy. WRS: And he asked me what we called that mule. Rita: And that is not what he called it, but we called it sweet old boy. WRS: Called it sweet old boy instead of that. Rita: So then, when he would grow that tobacco, you know. That was the thing. You just got paid in the tobacco business once a year. Once a year for cattle, hogs, or tobacco. WRS: And your payday is just once a year Rita: And every Christmas when we sold that tobacco, we had a steak, out. WRS: Say that again, mama. Rita: I said every time we sold that tobacco we ate out and had a steak. WRS 7 But then we used to, we had an old couple that used to work tobacco every year, two men and their wives. And they thought Rogers’ wife ought to work tobacco too. Because they thought she might think she was a little better than they was. But that wasn’t true at all. But he insisted and I saved my leave and two weeks at Christmas time I took my annual leave and worked tobacco to make him happy and those old ladies were happy I was helping. I got better than they did, I could pull more than they could. And they always brought lunch. WRS: Well, you know it never was a comfortable job until they started helping us, and then I thought those ladies would freeze to death so we got housed in an area so we could work inside where it wasn’t too cold. But you have to--when you work tobacco it has to be pliable. You can’t just handle it. If it’s too dry it all shatters out and there’s no way to get it to stay together. But it was a lot of fun, and we worked it on the farm. We loaded it onto trucks, took it to market, and stayed with it sometimes until it sold. You were rich. You had money in your pocket. Might not have been much… HM: How did farming and agriculture affect your role in the community? WRS: Well, I was always a part of the community-- the church and school. I don’t know how long I was into that, I was on the school board one time. And then I’ve been president one time of the Farm Bureau and all the foundation boards of the different colleges around over the state. I had a good time, took her on a lot of them. She’s my bashful barefoot boy and my bashful barefoot girl. But it’s been fun, and it’s been a challenge. But I guess it was a good time for it because it’s been growing, growing, growing, growing. EGM: When did you stop growing tobacco? WRS: When? It’s been several years, it’s been about five or six years hasn’t it momma? Rita: It’s been longer than that. WRS: But that was the crop in these western counties. It was… Rita: He grew sheep. Did you know he grew sheep? WRS: And I marketed them up there in her [Elizabeth Gillespie McRae] town. I was told her, it was one hundred and eighty miles from where she’s sitting to the market in Abingdon [Virginia]. Rita: When William was a little boy he went to the cattle market. Rogers, his granddaddy, they took a load of cows to market, and there were some sheep there, and William thought they were the grandest thing he’d ever seen in his life. He wanted those sheep and his granddaddy bought those five sheep and brought them home. And his granddaddy laughs and says to me, I never thought I’d be in the sheep business. But Rogers kept buying sheep, buying sheep, until we had a whole lot of them. And you know what one sheep does they all do. I don’t know if you know that WRS 8 or not. If one sheep would go through there then they all would go through there, if one fell in a hole and got out, the all did. WRS: And it was always on Sunday. Rita: And so when the little sheep come in the winter time. For babies, we had a nursery for the momma and the babies. So we’d go feed those sheep. William was not there all the time now. He was growing up. But they were afraid of bats, and we’d put the momma and the baby in these little places EGM: What were they afraid of? Rita: Bats. But, I didn’t know they were in there. They didn’t bother me. I have always been the scapegoat. WRS: But the better farmers, the farmers that made it, had the better land and they of course had the better land. But some of the farmers had to lease land too and that’s true today, These boys, these boys here, they lease land for growing tobacco and tomatoes. Well they don’t grow tobacco anymore but they used to grow tobacco. Rita: But all the families used to help each other, that’s what you’d ask in the community. WRS: Yeah, the families worked together. Rita: Because they would have cows so if he wanted a calf. He was the vet sort of for the whole community. He always had to do that. Of course, if he needed something done then they would help him, the cows would have babies and they used to call him saying these cows can’t have these babies without someone helping them. They always called Rogers. He was sort of like the community vet. All the farmers called him. They put up hay. WRS: Yeah so we swapped labor back then now most of its hired, or we hire it all--the Mexicans. We’ve gone in from where we started, you needed a project that could raise your family. They needed educating and we didn’t think about education back then like we do now. We lucked out, I guess on getting some of the better land in the county. We got the Ferguson place up there and you see what went with it. There was not a building on it, it’s just a place to get off one road and on to another. HM: Were there any challenges with agriculture in this area? Any particular challenges? WRS: I mean that’s what they used to make a living, but the challenges were the…We sort of had the competitive attitude, you know, you always tried to have the best horse, the best cow. You couldn’t be dragging your feet. WRS 9 HM: Yes, sir. WRS: And the farmers used to say some of the jobs on the farm took more than-- you couldn’t do it by yourself--so you’d help the neighbor’s farm to get his done, and he’d help you get yours done. You would work together on a lot of projects. But my granddad, he would know…I try to remember how old he was but he wasn’t really that old at all. And he had four daughters. Mom, you can help me with my ears here, if you will, when you get back. HM: Would you mind if we talk about the war a bit too? WRS: Well that’s what happened to my generation. Now, see they grew up to be the generation, the best generation for work and progress and things happening during those years, and I was in the Navy. HM: Were you drafted or did you enlist? WRS: No, I volunteered. And a lot of my classmates. I graduated from high school in 1938—is that a long time ago? And at that time the gunboat Asheville had been sunk, and all the crew had gone away they were looking for volunteers to replace the crew on the gunboat Asheville. I believe that was in 1937. I wished I had brought that with me today. And we left Asheville in a train load of us and from there we separated and went in different directions. HM: How old were you? WRS: I was born 1920 and that would have been 1941 or 1941. I would have been twenty-one or twenty-two, and I went into the naval air force and I was with the army B-17 squadron in the navy, stationed at Willgrove, Pennsylvania, when I got out and belonged at the Cloverleaf Country Club. That was the only place in the navy I ever was where you could go in to eat and cook your steak the way you wanted it, your breakfast would be prepared and all that kind of stuff. I worked with the weather bureau that was my job, forecasting and still the weather’s just as variable as it’s ever been, and sometimes you surely guess wrong. But that squadron that B-17 squadron, VP-101 they were doing radar research at that time. Everything used to come in on teletype or you had to pencil it, pencil it, pencil it. Then with this modern stuff all you do is move the screen and there it is all done all visible at the push of a button. But I was in Iceland longer, no England, I guess, longer-- about twenty-three months over there in Devonshire, England. Because I stayed in Iceland that was a good duty. Because you think you’d freeze to death up there but the coldest I’ve ever been was sitting there at Reykjavik-- that gulf stream came in directly nineteen above was the coldest. It’s been that cold here a lot of time. [Raining hard] WRS 10 WRS, 3rd: I’m going to roll your window up, can I see your car keys? WRS: 42:57-43:28 I don’t know what I did with my keys. There they are. His legs work a lot better than mine. [Rain makes it difficult to hear] but this farming back, it was always [inaudible] you were always working at the head of this [inaudible]. You’ve got two dollars to spend. Land back then, the 43 acres I bought at the head of this holler. And this woman come up from down east somewhere, she was Edith White and she come over there where I was working and she said I come to sell you this land. And I was home by myself….. my family was [inaudible] 44:24-44:37 but anyway Edith come in and said I’m going to sell you this land and it had a house on it. The family lived there and they had gone to Washington State but she asked me for a thousand dollars for that 43 acres. So, I bought it. I bought that and bought other tracts and added to it and added to it. And then, I inherited some. HM: Was it hard to readjust to farming after coming back from serving? WRS: No I enjoyed farming, I was…really got into the Dairy Queen in 1951. So, I had the Dairy Queen in Cherokee and Brevard, and they did very well at the time. I was asking the old boy up there at the Dairy Queen how much do you get for the smallest ice cream you sell? So he figured it up. What did he tell me, momma, for the least cone of ice cream? About a dollar and forty-eight cents, and he could sell me for almost 2 dollars. I told him when I was started into the Dairy Queen business, I could sell a cone for a nickel. HM: Did you make any friends when you were serving in the navy? WRS: Yes. HM: Did you keep in touch with them when you got back? WRS: [Heavy rain – difficult to hear] I had John [Bleeze] who married in high school [inaudible] we he came into the Navy. [heavy rain] My neighbor who I knew here she had an apartment in [inaudible] [since John and Mary were married she said, I’ll just move out of my apartment and move in with my sister. So she moved out and John and Mary moved in. I haven’t called Mary lately, but John died. [deleted about two minutes of talk about friends washed out by rain] WRS: But anyway back to this tobacco that was one thing, and then we got into hydroponics and that—we grow hydroponic lettuce now and that’s turned out to be a good market. So that’s what we do now. William did that. And I was so thankful that when he (William) and Drusilla my daughter who’s older they went to the University of Tennessee and William studied agriculture and I was so glad that he decided to come back and farm not that it was a good idea but it was a relief for me. He got into it and he has been into it some twenty years. The hydroponics are more than twenty years old on this farm and we sell the lettuce to the Ingles and Food Lion. Food Lion is the best for us. Last week they bought twelve hundred cases of lettuce, that is a lot of lettuce. But we got into it back when I was making the changes, you were getting into something your WRS 11 family could work at. But they used this hydroponic lettuce in Europe where the family would have greenhouses and the whole family would put their time into it to have cash coming in. But it didn’t work that way for us because we had to have more labor so we just hired them. And the cattle business I got into that through a change I made in that. In the dairy industry, I’d take the calves when they were babies and they would go back to them when they were ready to milk or to breed. And that turned out to be a real good business because we grew the feed for them. We’re using that land now for vegetables. In agriculture, a man told me the other day, he said the only reason I wanted to be a farmer is because it always keeps you making investments he wanted to take a chance and agriculture is one of the chanciest investments that you make. But it’s getting to be more, everything is organized now. Even the people who buy the vegetables for the grocery chains they buy those groceries through a company it puts that product on the shelf in the store, what about that? You don’t pay the bill with one person. And that boy right there can tell you a sad story, I think he lost about one hundred and twenty five thousand dollars this year on the farm. And got a baby in shoes on top of that. EGM: How’d he lose all that? WRS: Well his crops, he just couldn’t get them sold and it cost that much to produce them and he didn’t get any money back. But he’s trying again this year. But he’s been in it a long time and I don’t think he’s hurting too bad. And we used to work because people were trying to buy what you had to sell for cheap, they had no consideration of you being a nice man or a nice woman or a nice person or if you needed help. They’d take advantage of you. If you had a product that you couldn’t sell to nobody else they’d buy it, But I think they finally got the idea that somebody has to produce that product in order to make a profit. Now they consider that availability at the same time, if you’ve got it you can sell it and guarantee that you’ll have it there, that sign right there, Ingles sent that, and what we do for Ingles we grow the tomatoes for them, package them, and they’re delivered well they pick them up. They were wondering if we could extend the season for this product, the Mountain Majesty tomato. But they got the idea that we could extend the season if we grew in Florida, and Kill the goose that laid the golden egg. The mountains are a great place to have good vegetables. They’ve got the idea now we’ll use local, William is more gifted than I am. But it has worked and it is great. But if I was going to do farming I would decide what kind of farming I was going to do I’d study the conditions that was best suited for that. And I’d take a little tour and I’d find that kind of city and I’d just move in on that rather than have to repair whatever is already out there. But here… WRS 12 It has been good for me. The one thing I piddled around and almost missed out was a family. Everybody needs a family, whether you like them or don’t, Rita: Now what did he say about me? WRS: What I was doing, I was about to miss out on a family. Everybody needs somebody whether they like them or not. I was thirty eight when I got married and our first child came when I was forty so we’ve got children. Well Will is the oldest of our grandchildren, right Rita? Momma come on over here so I can hear. Rita: Sometimes I’d get so aggravated at him, he’d stay on this farm and work until ten o’clock at night and I worked eight hours and I’d get home at five and there was dinner and dishes and children to be put to bed. WRS: Well, see, I wasn’t working to get the hours in I was working to get the job done. Rita: And then I’d take my little children over here and his mother would come with us to see if he had died on the farm or something. I have done it plenty of times. He worked all the time. WRS: Well I worked at the Dairy Queen too, that was a pretty good job Rita: He couldn’t stand to work at the Dairy Queen, he had two Dairy Queens, one in Cherokee and one in Brevard where the college is. And he , and that’s where the money was, so I really worked so he could farm and we always had a little money tucked away if the children needed something at school or needed some money in their little banks. I love you dearly. WRS: Sometimes it is hard, but it is good. HM: How many children did you have? Rita: Two, William and Drusilla, but if he had noticed me ten years before that we would have had four. I would have loved to have four. WRS: You must have been having fun. Rita: Well, I was. I went to every party the ASCS had. WRS: Mama, will you please move over here so I can hear what is going on. She has gotten old like me. Rita: I am not far behind you. WRS: Farmers’ wives take a lot of abuse, they get old and stiff Rita: Farmers’ wives also had to run the business, the tourist business his momma had. We had those four cottages and I’d have to get up and if people left I had to clean them before I went to WRS 13 work and people who didn’t leave until later in the day I had to clean them when I got home. After I retired, I said that I will never clean another bathroom. WRS: But being in this business we’ve met a lot of nice people, and I think we are pretty nice people too, but we haven’t decided where we belong. But through the International Youth Hostel this group, it’s still in existence. And I got through that and when I was in England I had a place to go and stay. But I didn’t know I was supposed to learn anything from all those people good teachers from the university, university systems in North Carolina, in Florida, anywhere there was a university. Teachers would come in the summer. I had the privilege of knowing them. I also kept up with the navy and also my girlfriends still stop by to see me after seventy years. Rita: He did keep up with his Navy friends. They are all gone, but one of his Navy Friends wife, he calls her all the time. WRS: They were from Cincinnati. Those boys that would come down they thought being from the South had some ethereal quality, and I guess I am. Over there, this youth think, the kids back then they were allowed to … They rode a bicycle or just walked. They were supposed to do about 20 miles a day and you couldn’t spend more than 1 dollar and a nickel a day. I guess Killfeather was my choice of friends. I had a few Irish Thomas Charles Killfeather. They lived in Pennsylvania, Drexel, Pennsylvania. Tom lived in one of these row houses, you know build side by side by side, about three stories each. You know he was raised in that kind of atmosphere. He went on to school. He wound up in the Navy. We wound up in Lakewood, New Jersey, at the [inaudible] School. He was a little odd, but he was all right. Rita: But you wound up a dirt farmer. WRS: I enjoyed it. I learned that you don’t need to own everything in the world, you don’t have to be first in line, just enjoy your with what you can handle, and don’t get too big for your britches. HM: Pretty good advice. WRS: We have had a pretty good life. Rita: That is what he would tell about the secret to a good life. WRS 14 WRS: I think Rita was made for a farmer’s life. She worries too much. Everything has to be done. Rita: I said to him, Rogers, I will live in any kind of house that you have for me as long as it does not leak and it is mine. I couldn’t stand it paying someone else for rent. WRS: Rita and I had never lived in a rented house until we got married. It was $40 dollars a month. Oh, Rita, me. You are a sweet old girl. Rita: He is a sweet old boy.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

William Rogers Shelton is interviewed by a Smoky Mountain High School student as a part of Mountain People, Mountain Lives: A Student Led Oral History Project. He talks about growing up in Jackson County and working on his father’s farm where he has lived since he was 6 years old and the changes that have taken place over the years, both in farming and in the county. He talks about joining the Navy in 1940 or 1941. And he talks about meeting Rita, his wife. Rita also participates in the interview.

-