Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2946)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6873)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

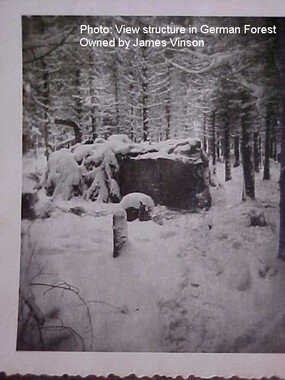

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1463)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (2008)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2569)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1923)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (195)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1672)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (236)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (519)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3569)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4912)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (35)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (13)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (215)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (982)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2182)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (86)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (3)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (185)

- Envelopes (73)

- Exhibitions (events) (1)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (815)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (6090)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Notebooks (8)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (5)

- Portraits (4568)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (181)

- Publications (documents) (2443)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Relief Prints (26)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (1)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (18)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (462)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1482)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1923)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (189)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (111)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (2012)

- Dams (107)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1184)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (45)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (119)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (72)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

Interview with Patricia Solomon

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

1 Solomon Interviewee: Patricia Solomon Interviewer: Mary Martinez Date: October 21, 2018 Start of Interview Mary Martinez: We’re here with Miss Pat Solomon. She’s my neighbor. And she was raised— born and raised where, Pat? Patricia Solomon: I was--My maiden name is Patricia Ann Anderson. I was born in Birmingham, Alabama. We moved to South Georgia, which is Albany, Georgia, when I was about two years old, and that's where I was raised, in Sylvester. First of all, it was Sylvester. We lived on a farm until I was in the fifth grade, and then we moved to the city of Albany. MM: So, tell me about your parents, and your birth order, your brothers and sisters. PS: I have an older brother who died of lung cancer about 10 years ago. I have two younger sisters and one younger brother. My younger brother is 24 years younger than I am. I didn't grow up with him, he’s like--I'm his mother this day and time. My father was a sharecropper. We all worked on the farm when I was growing up, and my mother got tired of it and said, “Look, I want to go to the city, so my father found a job in Albany, which is about 25 miles from North County, which is Sylvester, and got on a job at a service station. Then we found a home we rented, and years later, about four or five years later, my father became a policeman for Albany, Georgia, and we was raised in the city. Boy, we thought we were in heaven. But let’s go back to the farm. MM: When you say your father was a sharecropper, you didn't own the farm? PS: No, no. MM: Tell me about that. PS: Okay, a sharecropper would be where you would take your family down and work for somebody else. And when the harvest was finished like in September, then they would give you a share of whatever was sold, like cotton, tobacco, that's about what we raised, peanuts. And then in September is when we got a new pair of shoes. We only had two shoes, two pair of shoes, one for school, and one for church, and you didn't wear either one of them. When you got home from school, you pulled them off, and you with barefooted. And when you came in from church, you done the same thing. My grandmother made us dresses out of flour sacks. Back then the flour sacks were beautiful. She made our own slips to go under our dresses. Back then, you didn't wear shorts, or you didn't wear pants, all you wore was dresses. And we lived 2 Solomon on a farm, and right above us was a graveyard, and beyond that graveyard was a Black family, nicest people you ever met in your life. We all were sharecroppers. We all picked cotton together, we put in tobacco together. It was just a loving family. You didn't know if you are Black or white, we all wear the same. When it came dinner time, my grandmother stayed home, and she cooked dinner, and we would get a plate, all of us, Black, white, we’d go up there and get a meal, and drink iced tea out of quart jars, that's the way we drink tea. And I love tea as of today. But farming life as everybody knows, is a hard life from sun up to sundown. You didn't have a chance-- on Saturday we’d go to town, and we would buy groceries, and went to the movie for 10 cents in Sylvester, Georgia. And we had to love—it—I look back as the good old times back then because there was not so much killing or fighting, we all was just loving. And on Sunday you could count on a chicken, fried chicken and mashed potatoes. And we would have our family come over, my aunts and uncles would come over, and it's just one happy family. And the kids would get together, and we would go down and play on the sawmill. There was a pine tree growing up the top of the sawmill, and we climb that pine tree, and bend it over and let it go. (Laughter). And they kept on saying to us that the sawdust was going to swallow us, but we didn't believe it. So that's what we played. We didn't have a bicycle at the time. My brother got the first bike, and we all, the girls learned to ride on a boy’s bike, but we always found something to do. Back then our houses were up on blocks. You could crawl up under the house, and that's where me and my two sisters would go and play house. We would make mud pies, put them in the sun and bake them. And they had—of course, you were punished if you done anything wrong. But you had to go get your own switch. And if the switch wasn't right, you went back and got two of them, and then they plaited them together. But I look back now, and I said I'm so happy I was raised that way. MM: Why were you happy you were raised that way? PS: Because I learned to love, what love is. I learned what work was. It was just a loving time, really. It was just a loving time. MM: Tell me about your early memories of when you started to work on the farm. PS: My early memories, it's hard for me to remember. I do remember when we got out of school, first thing we did was go put-- I said we didn't wear pants, but we had overalls, we were overalls and a cotton sack. Granny made us a cotton sack to fit our size. And I remember I hated it. It must have been 110° in the cotton field. And everybody had their own cotton sack, and you had to pick cotton, and you put it on a cotton sheet, and whatever you made that day, that was yours. Well, for 100 pounds, we got three bucks. But we thought we were rich. And when we went to town, we really thought we were. I had plenty of money. And then in tobacco, I hated tobacco. I was a hander. You have to hand it off, and my mother would tie it. And you'd get sticky, that stuff is so sticky. But before you cropped it, you had to pull the worms off of it, and you had to kill them because they didn't have a lot of chemicals back then like they do now. But that's the memory. And hoeing cotton, we had to get out there and hoe 3 Solomon cotton, and that was just about a year. And peanuts, I remember stacking peanuts. They plow them under, no, we had to pull them up and turn them over, so the sun could dry them. Then you went back and raked them up and put them on a haystack to dry. MM: Wow. How old were you were you, do you think you were when you started working the farm? PS: I guess—I can—Probably, I must've been seven or eight years old, and the reason I say that is ‘cause my little sister is five years younger than I am, and I remember my aunt telling me that my little sister, we called Stinky, when she was walking up the path to go do tobacco, she looked at my mother and she said, “I don’t want to suck no damn tobacco!” And she was probably two or three years old. (Laughter). But she was tired of tobacco already and hadn't started. (Laughter). Then we moved to Albany, like I said— MM: No, no, no, back to the farm. PS: Okay, back to the farm. We had chickens. We had a billy goat, and we had a cow. Now Daddy milked the cow, and my brother milked the cow. And every time Daddy would go milk the cow, the cow would kick the pail over. So my brother had to go. Then we had a billy goat, and that billy goat loved everybody but my Daddy, and every time he went to that pen, he would butt Daddy, he would fight Daddy. And we even had a rooster that done the same thing. MM: None of them liked your daddy? PS: No, they must not liked men because—Well, they liked my brother. And then on the farm my brother he got a BB gun for Christmas. And he would shoot birds. Well, I didn't want him to shoot birds, I didn't want him to shoot nothing. So every time he would aim, and I'd see a bird, I'd shoo them off so he couldn't kill them. Well, he turned around and shot me with a BB gun. MM: Oh you’re kidding, where? PS: He shot me in the butt. MM: Oh my God. PS: And mother took the gun away from him for about a month. MM: Wow, wow. PS: Yeah, but we had--. And the schools, I can remember going to school in Polling, Georgia. This is what I remember mostly. For lunch, me and my sister next to me, Carolyn, we would take homemade biscuits and jelly to school for lunch every day. My brother got up early in the morning and went to that school to light the fires, so he could get a free lunch. But like I said, we look back and say, “Oh, what a terrible time,” but they were good times. MM: What did you have at lunch for school? PS: To tell you the truth, I don't know what they had ‘cause we never went to the lunch room, 4 Solomon we always sat outside on the steps and ate our lunch. MM: And what would your mother pack you for lunch? PS: Biscuits and jelly, that's what we had for lunch, just biscuits and jelly, that's all, and water. And it wasn't no bottled water either. She didn't pack the water, we had to go to the water fountain at the schoolhouse and drink water. MM: Tell me about your meals. What do you remember about your meals as a kid? PS: Well, the main meal was dried butter beans, lima beans, love ‘em today. Fatback, strick o’lean? MM: Strick o’lean? Strick o’lean? What’s that? PS: That’s fatback with a streak of lean in it. MM: Oh, streak of lean, okay. (Laughter). PS: Streak of lean, and a lot of times, Mother would make a hoecake of flour bread, not cornbread, flour bread, and we would have that over gravy, or syrup. But my best, the one I liked the best, was cornbread and milk. And if she could get a hold of cracklin’, we had cracklin’ cornbread and milk. But I can remember the first stove we had was an old wooden stove, and we used to have to go out, and my brother chopped the wood and we brought it in. And we had a well at the end of the porch where we got our water. So we had to draw water. And for a bath, we would draw water and put it in a number 10, number three, ten, what am I trying to say? Washtub. Number three washtub. And then what we would do is draw the water, put it in the sun, and all of us would bathe out of the same water. MM: Wow. So do you still eat any of those things today? PS: Yes, yes, I love cornbread and milk, I just don't like biscuits. I like biscuits, but I don't like the gooey part inside. I take the gooey part out and eat the hard part. And grits, we had plenty of grits. I can't ever remember eating oatmeal ‘cause I didn't like oatmeal. But I'm trying to think, like I said before you can count on Sunday's lunch that we were going to have chicken ‘cause we raised our own chickens. And Daddy would go out and kill one, and if he was too old, we had chicken and dumplings. But again, like I said, it was a good life, it was a good life. MM: How did you feel about having to work so hard in the fields? PS: Oh, It made you angry, but the problem is everybody around us worked in the fields, so we didn't know when anything else was except field work. And of course, you’d get tired. We’d run up, and when we were picking cotton, we find the biggest cotton stalk to get under the shade, and of course, you know you didn't get no shade in no field, but we thought we did. And then 5 Solomon when it came at end of the day and you weighed, we wanted to put some rocks in our cotton, so it would weigh more, but of course, we got discipline for that because that was—You were not supposed to do that, you were cheating. That's what we were taught. So – MM: And you said you would make money and you thought you were rich, and you would go to town, and what would you spend your money on? Or how much? Do you remember how much you would make? PS: Three dollars. Three dollars for 100 pound, and it’d take you a whole week to get the 100 pounds, but I know we go to the movie for a dime, and I'm sure we must've picked up a Coca- Cola and popcorn. And then of course, we would go buy candy. I'm trying to think back then-- it's hard to remember way back. MM: Did you have a five and dime store? PS: Yes, we did, yes, we did. We went into that and of course, everything in there you wanted. But we always find something for Mother and Daddy. I don't know, but we just—every one of us. MM: Really? PS: Yes, it may have been a little trinket or little angel or little something, and we would give it to Mother and Daddy. MM: Oh, wow. How do you think that upbringing on the farm influenced your attitude about work? What are your attitudes about work? PS: My attitude about work is work never killed nobody. And if you're going to get somewhere in this world, you need to work, you need to work for it. I enjoy working. I enjoyed working, I enjoy helping people. To me, working was just, that's just the norm, you were going to work. You weren’t going to be lazy. So, we all learned work ethic from working on the farm. MM: Do you think all your brothers and sisters have the same work ethic you do? PS: Oh yes, oh yes. Yep. My older brother worked with the railroad for 30 years and he loved it. My younger brother is a IT and he works all hours of the day and night. And my sister retired, one of my sisters retired from Burlington and the other one retired from Maryland, County of Maryland, I think it was Rochester, no, Rockville, Maryland, I think. But anyway, we all retired from something. MM: So you said that your mother got tired of-- Tell me about that. Got tired of working on the farm. PS: Yes, yeah Mother, she would get up early in the morning, real early, 4 o'clock, she'd have to 6 Solomon get up at 4 o'clock. And then of course, when we came in at night, and Saturday when we got back from town, that day was washday. We had to build a fire in the wash pot. We had to cut wood and put it in the wash pot. And of course, anybody knows how you do the wash pot, you boil ‘em. And then you have 10 tub sit around for rinse water. And you had to draw water from the well to fill out those tubs to rinse. And then we had a clothesline, and of course, back then, everybody had clotheslines, and we hung everything out on a clothesline. And my mother was very, very clean. I guess that's where I get mine from ‘cause when it came summer, we took everything out of that house, including the mattresses to air out in the sun. We would use Red Devil lye to clean the floors and then we would put everything back together at the end of the day. And then when it came Fall, we done the same thing at Fall. And I think there was only three bedrooms. Mother’s and Daddy’s bed, and the three of us, there were four of us at that time, and my brother, I think slept on the pallet, but when it got real, real cold, Mother would warm a quilt by the fireplace, and you know fireplaces don't get warm, and she would wrap us all up in the same bed to keep warm, and warm some bricks and put the bricks. And when we ironed, we had one of the old irons where you put it by the fireplace and iron, and I thought, “Oh my God, I'll be glad when—.” Well, we didn't know what. You didn't have much electricity, he was pleased to get running water, not running water, electric lights. We had to draw our water from the well, and you had to use the outhouse. And every time you went to that outhouse, you kept looking for snakes, but we thought we were rich ‘cause we had a two-hole outhouse (Laughter). So, at nighttime, if we had to go, I’d get one of my sisters to go, and we would go to the outhouse. Sometimes we would just go to the edge of the yard if we just had to do number one, so we wouldn't have to go way out to the outhouse. But, as I sit here talking about it, I can just see us going to the outhouse. I can see us chopping wood. We had to have wood for the fireplace. And I'll never forget the first car that my mother drove. It was an old Model T and you had to push it down the hill to get started because it wouldn't start otherwise. Well she pulled it into the driveway, if you called it a driveway, it was a yard, and she was backing up and when she did, she hit the chimney and messed the chimney up. But that's where she learned to drive and ever since, she was like a freedom. She could drive anywhere she wanted to go back then so… MM: So, she had a pretty hard life on the farm. PS: Very hard life, very hard life, she did. She worked real hard and like I said, she finally said. “Enough’s enough.” And thank goodness I owe that to my mother for getting us out of there and moving us to the city where you really were a lot better off. The schools were better… MM: How old were you then? PS: I was in the fifth grade. When we moved to the city, I was in the fifth grade. And we lived in an apartment, upstairs apartment over Maury’s Grocery. And then another one came empty that was bigger, and we just moved across the stairs. And then when the one on the bottom came empty, we moved there, and then when one on the end of the alley was empty, we 7 Solomon moved there, and we was right close to the park. We stayed in that park all the time ‘cause we wasn't working on the farm, so we went to the park. That's where I learned to swim. When I was in the fifth grade, they took us to the YMCA. We had to pay fifty cents, and that's where I learned to swim, at the YMCA. And like I said, there was more opportunities now that we were in the city. And we lived 10 city blocks from the theater, but we would all walk to the theater every now and then, and then of course, we had neighbors then. And we got to know our neighbors, and we thought we was in heaven. We didn't know that there was neighbors next door. When you are on the farm your neighbor next door was probably two miles down the road but yeah. We played miles down the road, football, we played baseball. And the junior high was right across the street from us, and that's where we would go out and play and get together, the neighborhood, on Saturday and Sunday and that's what we do, we go play ball. And after mother moved and we got a car, my mother became a waitress at what they called Radium Springs, and in the summer time my sister Carolyn and I worked at Radium Springs. But our biggest entertainment was roller skating. Everybody met at the roller skating. We learned to-- my younger sister, which we call Stinky, which her name is Linda, she learned to dance, she learned to do real good. She certainly was a good skater at that time. That’s all the entertainment, the movie and the skating. And then I went to work for “The Three Little Pigs,” I think that was the name of it, and I was a car hop. And that's where I learned to-- I can make my money, and I enjoyed it. I enjoy talking to people, enjoyed it. When I got out of high school, my older brother had already joined the Navy, and I knew I was not going to college ‘cause I had enough school. So I called my brother one day and he said, “Sister,” which they call me, “Why don’t you join the Navy?” I said, “I’m thinking about it, Wendell.” He said, “You can make whatever you want to make out of it.” He said that, “When you get out, you'll have a education, they'll pay for your education.” So back then I was very active in the East Albany Baptist Church. So I went to my preacher and I talked to him, and he said, “Pat, you can be a missionary anywhere you go. And other field is good for missionary field was the United States Navy.” So in 1963, I joined the Navy. I went to boot camp in October and got out in January. I was there when President Kennedy got killed in boot camp. Then I came home on liberty and I stayed home a week. And of course, they put your name and picture in the paper that your home on leave and all that. So when it was time for me to leave, they always said, “Don’t put your orders in your suitcase, you keep the orders in your hand.” Well I was going to put them in the suitcase, and my mother said, “No, you better hang on to ‘em.” I said, “Okay.” Well, when I got to Norfolk, Virginia, and I rode the bus, Trailways, I rode the bus. When I got to Norfolk, Virginia, somebody had stolen my suitcase in Fayetteville, North Carolina, and I said, “Boy, they were in for a shock because all that was in there was Navy uniforms.” But then I asked ‘em, I said, “What am I going to do? What are you all going to pay me?” And they said, “You need to go back to Fayetteville, they found the suitcases. It was a bright red suitcase my mother had given to me for Christmas. And when I went there, there was nothing in there, just suitcases. I'll never forget that, and the only thing they paid me was $25 And it said on the ticket that's all they allow. And who reads the ticket? And you know, back then, you couldn't afford to buy all this insurance, so here I was in the Navy, thank God I did have my orders, and they went into 8 Solomon the clothes barrel, I call it, the clothes closet, and got me some uniforms. And I stayed in Norfolk, Virginia until July, 1966. Then I got out of there, and I met my husband, and we got married in ’65, moved back to Fayetteville, North Carolina, which I never dreamed I would go back to that place. But I lived there for 30 years. I lived there for 30 years. I became the Hope County veterans service officer for 30 years. I believe I went in in 1966 and moved to Black Mountain in 1993. I was a tomboy, and every time the neighborhood guys would get together and needed somebody to play football or baseball, they would call on me. And I'll never forget there was a boy down the street that would pick on my sister next to me, Carolyn, and I had just gotten tired of it. And I walked with Carolyn, and he came out, and boy I jumped him. I caught him with my fingernails and everything, [and he said] “I’m going to call the cops.” I said, “Please do, ‘cause my Daddy’s a cop. Go ahead and call him,” and he called the cops on us, and Daddy came out and of course, I got in trouble for fighting, but that's okay. Hey, that was an accomplishment I made myself. MM: You were saying that when you moved to Albany, was it, that the school was much better schooling. Tell me about the schooling where you were on the farm as opposed to the one in Albany. PS: The school on the farm, you didn't have a lot of school supplies, and all I can remember is that we shared schoolbooks. You may take one home one night, and the next person would take the same book home, but you'd get their book. And really, I guess I've blocked out a lot of memory of the school, going to school. MM: Do you remember any teachers? PS: No, I can't remember any teachers. The only teacher that I remember was in high school. Her name was Mrs. Futch and the reason I remember her is because she said, “Are you Wendell Anderson’s sister?” And I said, “Yes, ma’am.” She says, “Well I hope you're not going to be like him ‘cause he never raised his hand, he just got up and spoke.” He just spoke out, and then they put them in the hall and they would whip him with a paddle. And I said then, I said, “Nope, you don't have to worry about me” ‘cause I was real quiet and I didn't even want to get up and speak in front of nobody. I really was not outgoing in the school around a bunch of people and individuals, and like I said, the guys treated me just like one of the guys. So we went dove hunting, we went up to the— I was not a talkative person in a crowd. Now, individuals or my neighbors, we talked, and I could hold a conversation, or I could fight just like they did, play ball, football, anything you wanted to do, I could do it. I guess I was proving to my older brother that I was on his level. But when we lived down in the first apartment, we had a river called Flat River. This was little Kinchafoonee Creek and it run a long, long way and it had a bridge across it. So, we all, and when I say we all, it was my sister Carolyn, my brother Wendell, my neighbors Ray L. Moore, Gene Summerford, we all went to Kinchafoonee, and they would jump off the bridge. And I 9 Solomon said, “Okay,” so I jumped off the bridge. Well my sister Carolyn went home and told Mother we jumped off the bridge. Well we didn't go there anymore, and we wouldn’t let Carolyn go with us anymore either ‘cause she was a tattletale. But we thought we was doing great. We had a swing that you could swing out into the creek, it was like a tire swing. And we had fun, we had to make our own entertainment, and we did make our own entertainment. And we had a mulberry tree right behind the apartment, and we would go and climb the mulberry tree, and eat mulberries. And then we also [went] behind them where they cooked pigs, and they had cracklings. Those were the best cracklings, they were homemade cracklings right there, you bought them right there. We used to go up there all the time and enjoy good old homemade crackling cornbread. MM: You were saying that you talked to your pastor before going in the Navy and that you could be a missionary anywhere. Tell me about your early days of going to church and how that—and your church history. PS: I first started going to East Albany Baptist Church and it was probably eight miles from my house. MM: Did you go to church on the farm? PS: Yes, my mother would take us to a church, and it must have been a Holiness church because the way the music, I can remember the music. And we really, every Sunday, we went to church. And again, you met people that you thought you knew for years because like us, they were farmers and they didn't act better than you were. We were all in the same boat. I enjoyed that, but I can't remember, and I can't remember much about that church, but when we moved to Albany, I started going East Albany Baptist Church and why I found that church so far from the house, I don't know, but I started going and got really involved. And I can remember all the songs. Back then we sung “At the Cross,”, “We’ll All Meet in Heaven,” all the older songs. I can't remember, “Glory, Glory, Hallelujah,” no that’s-- We sung all the old gospel songs. They had a guy that played the guitar, and everybody sung. And we’d have singings, and I would not miss a Sunday. I would not miss a Sunday, if I had to walk to church. Of course, we wore dresses and we wore heels, not high heels. And going back, for entertainment I can remember when Elvis Presley came to that little town. My Daddy was a guard, a policeman to keep people from going in, so he got us tickets. And me and Carolyn went. I'm telling you, if I could remember, I wish we had phones back then, we could take pictures. Of course we didn’t. And it was so exciting that you couldn't tell anybody how great that feeling was. And then the next one that we went to, that come up to the auditorium, was “Gone with the Wind.” Oh, was it lovely, and they had an intermission, of course, and I thought this is the longest movie I'd ever seen in my life. But you had everybody was sitting still, and then at the end when he said, “Frankly, ma’am, I don't give a damn,” well we all… ‘cause you never heard anybody cussing. That was a no-no. But that was an enjoyment, those were really enjoying times. We would walk to the auditorium because we only have one car and Daddy worked mostly at night to start off with as a cop, as a policeman, and he walked the beat. And if we were out 10 Solomon that time, he would go to work at 12, and not get off till eight or something like that, but every time we dated somebody, now this is the funniest thing, every time we dated somebody, he looked up the record. And he told us that we couldn't take them. I was dating a boy across the alley, and everybody that lives in the city knows the alley. You just walk across the alley and my boyfriend lived here, Gene Summerford. When we first started out talking and we go to my brother's dog house, they had a dog house and we'd sit on the doghouse. Well, my uncle started calling it the dog house romance. So we graduated from there and then we started dating, and mother let us use her car if my brother didn't have it one Saturday out of the month. And his daddy would let us use his one Saturday out of the month. And then when he would come over, we would be sitting in the same chair, and my daddy came in, and he says, “Sister, there's a chair over there and it's empty, you get over there. This is not the way we do it. You sit in that chair.” I said, “Okay.” So we never did sit together as long as the parents were around. But a dog house romance. And me and the guy that I was dating then named Gene Summerford, I joined the Navy, and I said, ‘Why don't we join the Navy together?” And he said, “No.” So I went ahead and joined the Navy. We went together I guess seven years, and when I was in boot camp, my sister wrote and told me that he had gotten married. So I knew he couldn't have known that girl that long, or he was dating her when he was dating me, whatever. But I'll never forget when we broke up, I was seeing another guy, he was a [dentist] – he made false teeth down at the end of the road, can't even think of his name now, that's how important he was. And I stayed after school, I didn't come home from school. I stayed down there and talked with him a long time. And my daddy was looking for me. And my sister Carolyn told him that I probably run off and got married. Well my ex-boyfriends brother said, “When he went up that alley, you could see a ball of fire going right behind him.” Boy, and when he finally got to me, you better believe I came home right after school. But again, I said, “Carolyn, you’re just a tattletale and you are not going anywhere else with me.” But those were good memories. And I'll never forget, there was a boy that was raised with me – Ray Elmore. He worked at the sawmill and he was probably 12 or 13 and we would walk around together. And I'll never forget. He had a cigarette lighter and it wouldn't light, so he put a dime with a cigarette lighter and threw it away and said, “Now I threw something worth of something away.” And I had never seen nobody do anything like that. I thought, “Are you crazy?” And he said, “No.” So I went over there and got the dime. But he had to put a dime with it to say he threw something away. But we stayed friends, in fact he calls me today, and that was back in the 50s. He got married at 14 1/2, him and his wife lived together until she died about four years ago. But every time I come home for leave, or every time Wendell would be home, and when we wake up in the morning, you might see him on the couch ‘cause we never locked doors and we never locked windows. Anybody could come and go. So one day, Ray and my brother, Wendell, had gone hunting, and they came in with the shotgun, and the first thing Daddy asked is, “Did y’all [remember to] unload the shotguns?” “Oh yeah, we unloaded ‘em.” Well Ray was sitting on the couch and when he did, he put his gun down, and when he did his finger hit the trigger and shot a hole in the ceiling. Scared everybody to death. Daddy said, “I thought y’all told me those guns were unloaded.” “They 11 Solomon were, we saw that they were.” Well they wasn’t, so everybody now in that household made sure all the guns were unloaded. Of course, him being a cop, he was very cautious about that, and his gun was always loaded, but he always put it under the mattress. When he came home and went to bed, it was under the mattress, he slept on that gun because he didn't want any of us to touch the gun. But it was something to see my daddy from overalls to a police uniform, but it was a good thing. In fact, we look back, my sisters and I we get together, and we look back, and our cousins stayed in Albany or Sylvester and never got out, never made anything of theirselves. They’re still living down there in the same little place and they didn't grow. And I said that we owe that to my mother for moving us from there. MM: Oh you mean back on the farm. You still have people way back there? PS: Oh yeah, they still live right in that little one-horse town in Sylvester, and a lot of them live out on the farms. MM: Are they still sharecropping? PS: No, no. They’re not sharecroppers ‘cause sharecroppers is just about gone now. Some of ‘em are—Some of ‘em got married and didn't work. Some of ‘em became a policeman or a truck driver, or something on that sort, but they were scattered everywhere. And I got one cousin right now named Sue. She and I—if there’s anything happening in Sylvester, I would call her up and said, “Hey what’s happening?” and she would tell me. She keeps up with all that ‘cause there was a lot of our first cousins still live there that didn't move out. MM: Did you ever go back to visit? PS: Oh yes, oh yes. Me and Linda, Stinky went back probably about three or four years ago. MM: Oh really? What was it like? PS: Oh they had torn down the old house that we lived in on Fourth Avenue. They had torn all of that down, and of course when the storm came down through, it tore down a lot of the old oak trees. That town had beautiful oak trees and tore all that down. And the high school that we went to high school, and we only had one high school, and that was Albany High, and of course back then the Black people had their own high school, Monroe High. But they’d torn down Albany High. When I graduated, when you started out in homeroom, you may not know the person you're sitting next to, you may not see them until the next homeroom. There were about 500 and something of us graduate, so you really didn't get close. I got close to two girls. You really didn't get close to anybody. My boyfriend, Gene Summerford, at that time, and I always went to the senior prom, went to his senior prom, went to my junior and senior prom, and I can remember that. I can remember having-- I loved PE. I loved PE. We had home economics, which I hated ‘cause you had to learn to sew and to do this and that was not my cup of tea. I could I could not do that. In fact, at home when mother worked, 12 Solomon Carolyn would cook, and I said, “Carolyn, if you’ll cook, I’ll do the dishes.” And of course, she messed up every dish in the house. I had the trade-off ‘cause I didn't want to do no cooking. So she tried her best to mess up every dish in the house, and today she cooks just like mother did. She's a good cook. She can make the best chicken and dumplings, just like my mother. But nope, I was not an indoor person. I did not want to learn to sew. I didn't want to learn to knit. My grandmother try to sit me down to embroidery, and you know you had those embroidery things, and you had pillowcases. I ironed on the thing, and that was not my cup of tea either. I said, “No, this is not for me. Give me the yard.” So I traded off, I done the yard and Carolyn done the sewing and cooking or whatever she wanted to do. And my grandmother lived with us. I cannot remember a time that my grandmother did not live with us. It was my mother's mother. So we had two mothers discipline us. MM: Let’s pick it up next time with your grandmother. I want to hear more about her. (Audio for remaining interview is missing) MM: Okay and Pat, I was wondering whether you notice any difference in the way people today view work as compared to the way you viewed it when you were growing up and when you got older? PS: Yes, when we grew up, we had chores and we worked on a farm and we didn’t have time. And of course, we didn’t have what they have today. We didn’t have telephones, or TV, or computers but I feel like the kids in this day and time has missed out on a lot because they didn’t have to work as we did. Even today, they don’t even have chores. Some of ‘em do, I’m sure quite a few don’t so I think they didn’t have the opportunity to live on a farm or having to work on a daily basis. They don’t even get out and play like we used to play once. They come in and all they want to do is get on the telephone or the computer. I feel that if they had farm work to do or if they had to go and really work that the work technology for them would be a lot different today. They would see what work is all about. And I know a lot of the young people in this day and time don’t want work. They don’t even want to clean their rooms, much less work. So if they would just—If they could live like we did, I think there would be a difference. Of course, the world keeps changing and we change with it, and we as parents are to blame because we want them to have better than we had and not realizing that we were really spoiling them in that way. So I think that that’s the big question is that they don’t—And families don’t have family time anymore. Everybody has—the parents have to work and the kids raising theirselves so it’s a different world. MM: Thank you and thank you very much for the interview. I really enjoyed spending time with you. PS: Thank you, I enjoyed it. End of Interview

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Patricia Solomon discusses the differences in the work and schooling of her childhood between living on a farm in Sylvester, Georgia and then in the city of Albany, Georgia. She talks about her family and what life was like growing up poor, but happy. This interview was conducted to supplement the traveling Smithsonian Institution exhibit “The Way We Worked,” which was hosted by WCU’s Mountain Heritage Center during the fall 2018 semester.

-