Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (292)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2766)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1388)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (1794)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2569)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1923)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (161)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1672)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (233)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (519)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3524)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4694)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (25)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (12)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (212)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (981)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2115)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (84)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (184)

- Envelopes (73)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (815)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (5835)

- Newsletters (1285)

- Newspapers (2)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (6)

- Portraits (4533)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (151)

- Publications (documents) (2236)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (15)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Vitreographs (129)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (282)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1407)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1744)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (170)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (110)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (1830)

- Dams (107)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1184)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (38)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (118)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (71)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (244)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

Interview with Ron Rash

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

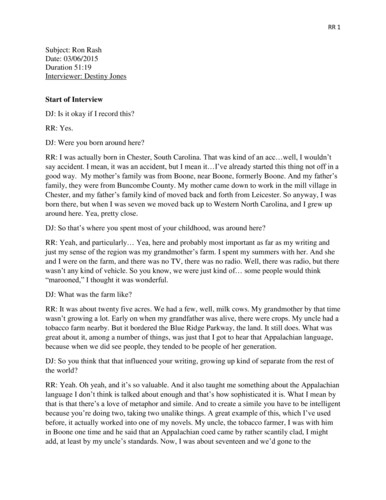

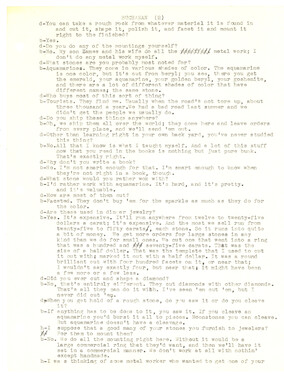

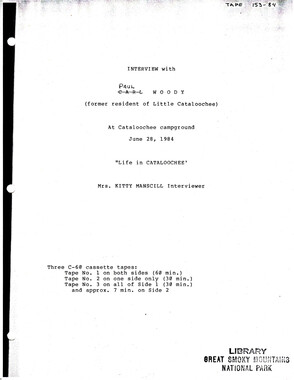

RR 1 Subject: Ron Rash Date: 03/06/2015 Duration 51:19 Interviewer: Destiny Jones Start of Interview DJ: Is it okay if I record this? RR: Yes. DJ: Were you born around here? RR: I was actually born in Chester, South Carolina. That was kind of an acc…well, I wouldn’t say accident. I mean, it was an accident, but I mean it…I’ve already started this thing not off in a good way. My mother’s family was from Boone, near Boone, formerly Boone. And my father’s family, they were from Buncombe County. My mother came down to work in the mill village in Chester, and my father’s family kind of moved back and forth from Leicester. So anyway, I was born there, but when I was seven we moved back up to Western North Carolina, and I grew up around here. Yea, pretty close. DJ: So that’s where you spent most of your childhood, was around here? RR: Yeah, and particularly… Yea, here and probably most important as far as my writing and just my sense of the region was my grandmother’s farm. I spent my summers with her. And she and I were on the farm, and there was no TV, there was no radio. Well, there was radio, but there wasn’t any kind of vehicle. So you know, we were just kind of… some people would think “marooned,” I thought it was wonderful. DJ: What was the farm like? RR: It was about twenty five acres. We had a few, well, milk cows. My grandmother by that time wasn’t growing a lot. Early on when my grandfather was alive, there were crops. My uncle had a tobacco farm nearby. But it bordered the Blue Ridge Parkway, the land. It still does. What was great about it, among a number of things, was just that I got to hear that Appalachian language, because when we did see people, they tended to be people of her generation. DJ: So you think that that influenced your writing, growing up kind of separate from the rest of the world? RR: Yeah. Oh yeah, and it’s so valuable. And it also taught me something about the Appalachian language I don’t think is talked about enough and that’s how sophisticated it is. What I mean by that is that there’s a love of metaphor and simile. And to create a simile you have to be intelligent because you’re doing two, taking two unalike things. A great example of this, which I’ve used before, it actually worked into one of my novels. My uncle, the tobacco farmer, I was with him in Boone one time and he said that an Appalachian coed came by rather scantily clad, I might add, at least by my uncle’s standards. Now, I was about seventeen and we’d gone to the RR 2 hardware store somewhere, and he looked at me and said, “That girl hasn’t got enough clothes on to wad a shotgun.” (Laughter) RR: If you break that down, that’s pretty brilliant. I mean, you’ve taken two very unalike things, and that kind of use of simile, just the delight in language, saying something in a memorable way. The other thing that became even more clear when I got into graduate school, and actually I was just reminded of this yesterday, I was reading a Shakespeare play. Lady Macbeth talks about being “afeared.” In Chaucer you hear vittles, victuals. Sometimes people think, “Well, these are just these ignorant Appalachian people,” and what they don’t get, is that language, some of it, it goes back to Chaucer and Shakespeare. DJ: It really is. Did you have any siblings growing up? RR: I’ve got a brother and a sister. DJ: What was it like having them around, and your relationship with them, do you think it influenced you as a person? RR: Yeah, we were very close. We never went through that kind of real fighting that sometimes siblings do, and we’ve even grown closer as we’ve gotten older. So I feel very lucky that way, because I have so many friends who haven’t had that experience. DJ: And your parents - were you close with them too? RR: Yeah, my father died fairly young. He had some pretty serious health issues most of our lives, and that didn’t enable him to do a lot of things that he might have done with me, but my uncles kind of took over. They were the ones that took me fishing and hunting. DJ: All the experiences that you had growing up with your family, do you think that may have influenced the way you see the world and the way you want to portray it in your writing? RR: Oh yeah, hugely. And I think particularly, not just my immediate family, but my grandparents and my uncles. Knowing them, and knowing the region, and the people in the region, I think the one thing that bothers me so much is the way people in our culture are depicted, particularly in popular culture. I mean movies, if a movie is set in Appalachia, you know mutants are going to be coming out of the ground, or there’s going to be somebody inbred. And I saw none of that growing up. They’re like people everywhere else. I think one of my goals in my writing is not to sentimentalize them, because like people everywhere they have their flaws, but to show that they’re human. Actually, I was doing an interview with a French – a French scholar was interviewing me recently and she was talking about the fact that I have a good readership in France, and she said, “it’s because people really identify with your characters.” Because France is actually, once you get outside of Paris, is a very rural country. That’s the goal. We’re like everybody else, ultimately. I mean, we speak differently. There are differences in the culture, and I bring those out certainly. But at the same time, if the characters aren’t recognizably human I’ve failed. You know, if they’re just exotic freaks. RR 3 DJ: Do you ever think you’re criticized because you don’t make them sound inbred and stereotypical? RR: I’ve had sometimes interesting reactions. Occasionally somebody’ll say, “Well you know, you show some of the darker aspects of the region.” Because I’ve written about meth addiction, which is a real problem, but I think I haven’t had a lot of criticism from people, either way. In the region actually, I mean I’m sure there are people that maybe don’t like what I write, but for the most part people say, “Well, I’m glad you’re bringing attention to this.” DJ: What would you say to those authors that do portray Appalachian people as monsters? RR: They lack intelligence, for one thing. They have a, they’re prejudice. The irony there is that such people would tend to think of themselves as enlightened in other situations. DJ: Do you think they view themselves as superior? RR: Oh yeah. Heck yeah, absolutely. I’ll give you a story with a faculty member who recently left here, so I can bring it up. He was from New York, and he said, “Well, you know, I grew up with books in my house, and people talked about intellectual things, and so it’s not surprising that I’ve become an artist, or whatever.” I mentioned there was a writer from Tasmania that I liked and he said, “Yeah, it’s weird isn’t it? That somebody can come from a place like Tasmania and be a writer. And you!” And he pointed at me, and he said, “Yeah, you! You actually became a writer.” You know, like… (why I suck?) And this guy considered himself very liberal. He would’ve never said something like that about say, an African American. But it was just weird… I found it amusing. It’s a great story. I tell it all the time. DJ: It’s ironic how they portray themselves against Appalachian people. RR: Yeah. He was just clueless to how insulting that was. And he wasn’t being malicious, he just, it just hadn’t crossed his mind. DJ: It’s like second nature to him. Do you think that mostly people who write about Appalachian people as inbred or freaks, that they grew up, their parents taught them that or their grandparents, or just where they were they felt like they had more opportunities? RR: Yeah. Because the region has tended to be more isolated, I mean, any mountainous culture has to be. There’s always been a tendency to view, I think, Appalachia as exotic. This starts, people traced it back particularly in the early part of the twentieth century. They played up things such as the Hatfield’s and McCoy’s, and this idea that these people... And part of it, I mean there is some of it that was true. People tended to be more rural. They tended to speak differently, and obviously there’s some differences, but it became, you just kind of got this stereotype developed and people just believed it. DJ: There are different types of cultures in each Appalachian community, do you think they view each community different or…? RR: No! No, that’s it. They very often will say, look at say, Hazard, Kentucky which is a… or Owsley County, Kentucky, which is the poorest county in the United States, and they’ll say. RR 4 “Well, that’s all of Appalachia.” But, at the same time, there are problems here. I mean serious problems. Particularly in Eastern Kentucky right now. I mean that’s like being in the Third World, almost, because it’s so poor and you can’t drink the water. DJ: Do you think it’s like that because they want to be cut off, and they don’t want help from…? RR: No, I think that part of it is, and I’m getting it a little political here, but I think the coal mining industry is so powerful that they’ve been able to essentially just destroy the land. When I’m up there, I taught at a workshop in Eastern Kentucky, and you cannot drink the water out of your faucet. I mean, you have to import water. I’m not making that [up]. That’s a fact. The streams are dead, there are no fish in them, or a lot of them. Part of why that can happen there is because you have people who have this view, “Well you know, these are subhuman anyways, so what does it matter whether they have a good life, whether they have to drink poisonous water?” You know? That kind of thing. DJ: You’ve got to witness this firsthand, on what this can do to people. Being dirt poor and almost in poverty, but still do you think they can keep up their moral through it? RR: Well, I think that’s where you start seeing the drug problems come in, the problems with violence. Those things all come together, I think. And as I said, there are bad people everywhere. And I think one of the bad things that’s happened also is that unfortunately, sometimes the younger people, because there’s so little opportunity, have to leave and that’s not good either. Who’s going to stay here and build businesses? Who’s going to teach? Those things. DJ: Did you ever have to experience, like in your own experience have to be almost in poverty, or worry about food or clean water? Or did you have any friends growing up that had to worry about that? RR: I was very lucky because my parents worked incredibly hard. My grandfather couldn’t read or write, but my father quit high school. I won’t go into the story except he ended up working a full shift at a mill, and then taking night classes to get his GED and then to get his college degree. He ended up teaching. My life was pretty comfortable. But, my uncle, who was the tobacco farmer, they lived incredibly close to the bone, and I saw that. Particularly, when I was about fourteen their tobacco barn burned down, and it wasn’t insured, and that was a year’s, a few years’ worth of [money]. I’d go out to their house and it was just… I mean, I always felt guilty. I’d feel guilty at Christmas. I can remember when we’d get together at Christmas, I always felt guilty because they’d get so little… So that was tough. Yeah, I saw, yeah. And he was a hardworking man, and she was, my aunt. They worked incredibly hard on that farm. The money crops were tobacco and cabbage, and I can remember one time he drove down from Boone to Hickory to sell the cabbage, and the guy was going to pay him so little he just drove back up and just threw them, and let them rot. And so you see things like that, it changes the way you view certain things. (Long silence) RR 5 DJ: Do you think that maybe, not having a privileged life, but better than say, your uncle, do you think that maybe helped you not see the world around you as like falling apart? So you could look at every aspect and then find the dark things, but also highlight the beauty in Appalachia? RR: Yeah. I think it was an advantage, because… and I think the great thing about why I was able to become a writer was because my parents put me in a situation where they had worked so hard and come up so far - because my mom grew up on the farm - that I was expected to go to college. But I will tell you an amazing thing about my uncle and aunt. Their oldest son was killed when he was seventeen, my first cousin, in a car wreck. But the other three all got college degrees. DJ: That’s really awesome. RR: And I mean, they just did it out of just sheer will. So they kind of did what my parents did a generation later. DJ: Do you think this is still going on? Where some generations don’t go to college, but they expect the next to? RR: I hope so, but I think one thing that kind of bothers me, and this is around the United States, but I see it here as well, is I’m afraid that sometimes, I just get a sense that maybe a lot of people who are kind of in that poverty level or lower class are starting to feel more hopeless, and not quite believe that it can be done. To me that’s tra… that’s a horrible sign for us as a country. DJ: Do you think it’s more important to try and get an education when your parents didn’t? Do you think that being the first in your family to go to college, do you think that person should strive even harder or just…? RR: Oh gosh. Yeah, I think you got a huge obligation, I feel a huge obligation- to my grandfather who couldn’t read or write, because he got my father a little farther along. And my grandmother, even when my father quit high school, kept after him. I think one reason I write is to honor them. DJ: Are you married? RR: I am. DJ: Whenever you first met your wife, do you think that anything in your writing started changing? Do you think she had an influence on you? RR: Oh yeah, I think she’s been very encouraging. Living with a writer’s not easy. There’s always a part of the writer that’s – You know, I’m going to go into my office and write. And even when I’m there, I’m not there, sometimes. I married an introvert and that’s good. And the fact that she’s willing to - be ok with that, to be able to live the kind of life where she knows every day for five, six hours, I’m going to be somewhere else. DJ: Did she grow up in Appalachian Mountains? RR: No, she grew up in South Carolina. DJ: What kind of childhood did she have? RR 6 RR: She had a very middle class, more comfortable than mine. DJ: So, would you mind describing her a little bit? RR: No. She’s very driven, and she teaches high school. She teaches lower level kids, English. Great teacher and I think, very smart. Much better grades than I had in college. That’s where I met her. I met her in grad school. So yeah, just a bright, good, very impressive woman, I think. A very patient woman because she’s been married to me for thirty years. DJ: Do y’all have any kids? RR: Yeah, we got two. One’s twenty-seven and one’s twenty-five. DJ: Do you think whenever your first was born, do you think that that changed your writing? RR: That had a huge, huge impact. I think more so than marriage, because once you have children as you know all too well, it’s the most wonderful thing, but it’s also terrifying. And it’s terrifying because it really made me pay more attention to the world, and the way the world’s going, because I know my children will be in it even after I’m gone. I think if I didn’t have children, things would bother me a lot less, certain things that we’ve been talking about. But, knowing they’re going to inherit that world is… When that happened, one thing people noticed about my work was it got darker. It wasn’t so much that the kids were making me depressed, it just made me more worried about the world they were going into. DJ: Do you think that whenever your first one was born and you started seeing things, maybe not more clearly, but more cautiously, do you think that that worked into your writing? RR: Oh yeah. As I say, I think it had a huge effect. And then also, I just opened up so much, because when you have children it expands you. It makes you see things in a way you couldn’t have before. DJ: Do you think you started thinking more about how children were raised and grew up and were treated in the mountain community? RR: Certainly. Because you’re with other children, and their friends, and you start to see how their families, their parents influences those kinds of things. DJ: So, you’ve seen a lot of different diverse mountain communities, do you think there’s a huge difference in every one? Like their own individual cultures? RR: Their each different, but I think there’s certain aspects that overlap. So many of the people didn’t- for instance, the Scotch-Irish influence pretty much- somewhere like Asheville’s going to be an exception, but for the most part, just look at the last names. They’re British almost. It’s changing now, and that’s had an effect. I think certain customs, the language certainly. When I talk to somebody in Eastern Kentucky, the accent’s familiar, little bit of a variation maybe, but the language is very similar. The simile’s even. And food, you know, the heritage. Quilting, which has been very important in my family, passed down. There’s certain things I think, are shared. Just as they would be say, in New Orleans. New Orleans has many very different RR 7 communities, but at the same time, there’s a kind of sense of you know, the food, the language, accents. DJ: Have either of your children followed in your footsteps, or your wife’s? RR: Yeah. My son’s an elementary school teacher, and my daughter’s getting an MFA in poetry, right now. She wants to be a poet, or maybe short story writer. I didn’t encourage or I didn’t discourage them. I think the good thing about the professions both have chosen is they’ve seen us, and they’ve seen the good and the bad of them. DJ: Do you think that what they say about, “If both your parents are teachers, you’re going to be a teacher,” or something along that lines, do think that applies to most teacher families? RR: I think just the fact that you see somebody doing the job. I think teaching’s a very honorable profession, and I’m glad I chose it. There does seem to be a tendency of sons and daughters of teachers at least think of it as being a possibility. So I’m sure sometimes it’s kind of passed on, and they see the rewards of it. DJ: Or like some families where both parents are hard-working at the mill or construction or something like that, do you think that that influences their children to want to maybe want to be an educator, or something beyond working with their hands? RR: I’ve seen it both ways. I had a relative, one of my cousins, his father was a really good woodcutter, I mean an artist. He made cabinets and- a carpenter, I guess. They kind of pass that down. He became one, and if my cousin had lived I’m convinced he was headed that way. So it works both ways. DJ: Has any of your family made their way into some of your writing? Have you maybe based a character off one of them? RR: More of my poetry. I tend not to be overtly autobiographical. But in my poetry, I actually wrote a series of poems about the death of my cousin, the one that died at seventeen. DJ: Would you ever consider writing about maybe, adding your children’s experiences into your stories, or even your own experiences? RR: Not my children. That, to me, would be a violation. That’s hard to articulate, but I wouldn’t feel good about that. I just wouldn’t do it. I would never write anything that they would recognize and say, “This is something that happened to me.” I don’t think. Maybe I will as I get older, but I try to, even like when I do interviews, I mean this okay for this, but I in a way don’t even want them to even be in that public connection. DJ: I noticed I couldn’t find anything about your… RR: And that’s why. And that’s to protect them a little bit. I’m not that well known, but, you know. DJ: I understand. Some of your poems and short stories and even your novels, have you ever actually talked to some Appalachian people and gotten their experiences to use? RR 8 RR: Oh yeah. All the time. When I wrote Serena I talked to old loggers, guys in their nineties. I did a huge amount of research that way. Family stories. Interviewed my… I was doing a book, my third novel, World Made Straight, a lot about tobacco. I knew some about tobacco, but my aunt, she had been doing that for half a century. It’s a horrible job, it’s a tough job. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen anybody do it, boy it’s nasty, hot job. We were talking about it one day, and she knew I was going to write about it and she kind of looked at me with a little twinkly in her eye and she said, “It’s a lot harder to do it than write about it.” (Laughter) RR: And yeah. Yep. I just thought, “Yeah, I know. I know.” DJ: So have you ever taken their firsthand accounts and actually kind of quoted it into… RR: Oh yeah. Even phrases sometimes. I mean, I let the people know I’m using it. DJ: So some of it, you might say is true? Actually happened? RR: Yeah. Some of the events that happened in Serena, for instance, with loggers, those actually happened. DJ: How do you fill in the gaps of these events? RR: Imagination. Empathy. That’s what it’s about. You just try to put yourself in- imagine that world. You do research, but there comes a time when you have to kind of take a chance. Just see. Just try to imagine from that point of view. DJ: How long were you writing before you decided you wanted to publish? RR: There wasn’t a time when I really didn’t not want to publish, but I didn’t really… I wasn’t writing well enough to where I should’ve published for a long, long time. When I hit about twenty-eight, twenty-nine, I finally started writing some things that were pretty decent. I didn’t start writing until I was about twenty. Nineteen. A little later than a lot of my friends. I didn’t really write anything good for a decade. DJ: You think over time, growing older, more experiences that helped you become a better writer? RR: Oh Yeah. The practice. It’s like learning guitar. I mean, you don’t just pick it up and start playing. It took practice. It took wrong turns. It’s learning the craft. DJ: What made you decide you wanted to write Appalachian historical fiction? RR: Well, it’s the place I knew best. Several of the writers I loved the most- I was reading Faulkner, particularly. O’Conner. I found that there was enough here, didn’t have to go to New York to write great books. There was enough in your own little community. DJ: Did you always want to be a writer? RR 9 RR: No. I actually wanted to be… my emphasis in high school, college, and even a little bit after college, was athletics. I was a pretty good runner. I ran in college, as well as high school. My goal was to make the Olympic trials. I was getting pretty close and I tore a hamstring, and that ended it. But, in a way it was a great blessing to me as a writer, because all that focus and energy I had learned, I just kind of shifted into writing. DJ: You said you wanted to focus on athletics. Did you always want to focus on athletics in college? RR: Actually, I was a PE major my first two years. I mean I’d always loved to read, but then I had a really good English teacher my sophomore year. And as I said, always loved to read, and I just started thinking, “Maybe this is more of what I want to do.” I think my goal would’ve been, when I was a PE major, would’ve been to be a track coach. I started thinking this literature thing- that’s when I started thinking about being a writer, too. So, I just drifted over there. DJ: One of your pieces is actually about basketball. RR: Yeah. DJ: I play basketball. RR: Well, I played with the greatest college basketball player in history, David Thompson. Have you ever seen him on YouTube? DJ: No, haven’t got the chance to. RR: Ah, he’s amazing. We grew up playing together, and he was so good. Yeah, you need to watch him. He won national championship. North Carolina State won their national championship, he was their best player. And I loved playing basketball. I just wasn’t very good at it. My brother was good. My brother was a 6’3” point guard. He could dunk the ball backwards. It’s funny because he had no drive. He could’ve played Chapel Hill. You know, Dean Smith would’ve loved his game. He was smart, great passer, athletic, could just jump like crazy, quick, and I just never could understand how you could be that way about something you were pretty good at. I’m sure you’re more driven. But I think sports are, I think that they’re very valuable to you. And as I say, I think they taught me so much about how to be a writer. DJ: Do you think that they help with really any direction that you want to go with? They can teach you discipline and focus? RR: Yeah. Sacrifice, teamwork. Yeah, I do. Sometimes we see the bad side of athletics, but my experience was that it was awfully good for me. DJ: Is there anything that you remember specifically that really changed your mind in college about wanting to be a writer? RR: Well, my sophomore year, as I said, my English teacher made me feel like, “Well you know, you’re pretty good at literature, you’re pretty well read.” I was such a horrible student in high school that, I’m not joking about that. I barely got out of high school. I went to college on a track scholarship. I never thought of myself as being that smart or smart period. I had trouble in RR 10 French. I failed French One. I had the lowest average in the school’s history. My Barbie Doll for my project that I set on fire and said was Joan of Arc didn’t help. She made me feel like, “Well you know, you’ve kind of got a talent for reading literature, or you seem to really get what’s going on. You notice things that other students don’t.” DJ: So, that kind of got you thinking, “Maybe I should dabble in this a little bit”? RR: Yeah. And the other thing was, I didn’t realize how well read I was compared to most other students, because I’ve always been a voracious reader. In high school, the things I was reading we weren’t reading in class so, it’s not like I was talking to anybody about them. I was just kind of off in my room. Then I got to my sophomore year in college and she said something like, “You’ve pretty much read everything, haven’t you?” And I thought, “I didn’t realize that, but yeah. I had read Dostoevsky, I had read Wolfe. I had read these people.” I suddenly realized I was better educated than I realized. DJ: So your English teacher was the main thing? RR: Yeah. DJ: Do you remember maybe, what was the first thing you started wanting to write about? RR: Yeah, I wrote about my uncle. It was a bad story, but he was going through a really bad time in his life, drinking, he had just gotten divorced. I wrote a story trying to get into what he was feeling. DJ: Do you feel like you connect to your characters through writing? RR: Oh yeah. You have to. DJ: So, do you ever use writing to vent, to put out your feelings and maybe not someone else’s? RR: Obviously my feelings are going to filter in. When I feel certain outrages about something that might be happening, either locally or even internationally, yeah, that has to filter in. But I never want it to be propaganda. And it ultimately has to be from a character’s point of view. I don’t want to impose my views on them, in other words. DJ: What were some of your dreams as a kid? RR: Baseball player, fireman, herpetologist. I loved to catch snakes when I was a kid. I wanted to move to Australia because they had the most poisonous ones. DJ: My sister loves snakes, too, RR: I didn’t really think that much about that. Looking back it wasn’t like I thought, “Well you know, this is the kind of career I want.” I was just kind of having fun, out in the woods, and reading, and being a kid. I didn’t think much about it. I didn’t think I’d be a teacher, which is kind of interesting. I never thought of that until I got into college. DJ: What about a novelist? Did you ever picture yourself? RR 11 RR: Oh, no. I never thought of that in high school, which is interesting because I was reading so much. DJ: Looking back, do you think that maybe there were early signs that you were into literature, but you just didn’t see it at the time? RR: Oh yeah. I mean, I was like a case study, because I spent so much time alone. I was on my grandmother’s farm in the summers. My brother and sister wouldn’t go. They found that incredibly boring. No TV, nobody else around. You know, my grandmother would pack me a biscuit with a piece of ham on it, and a jar of water, and I’d take off for eight hours. I wouldn’t come back. I was fourteen, twelve years old. Looking back on it, it was an incredible childhood that you could do that. I mean, you couldn’t do it now, and I couldn’t do it with my kids, but you could then. And I’d just wander the Parkway. Now, we had a lot of relatives around there, so if I got hungry or thirsty I’d just go to their house. But most of the time I was out there by myself, and daydreaming. DJ: Do you ever wonder if you came up with some good stories while you were daydreaming? RR: Oh, I know I did. Yeah, I know I did. I mean, that’s what I would just… Yeah, you know, just daydreaming, imagining things, and looking at the world, noticing plants, things I write about now. DJ: Have you been back to your grandmother’s farm? RR: Yeah, but it’s always sad, because some of the farm’s been sold off, and there’s some houses. A particular place that really meant a lot to me, there are houses on it now. When I go back there’s a real sadness to it. And it’s not so much that the people I loved are gone there. My aunt lives in her house. It’s just that everything around it’s changed. DJ: Are there any places that haven’t changed that you can go to and maybe look for inspiration? RR: Oh, inside the house, and the graveyard where my father’s buried, which is pretty close to there. That little church hasn’t changed much. I go there, and be among my people. They’re not going anywhere. DJ: What were some of your goals in college, once you decided to become a writer? RR: Just to be as good at it as I could. I’ve always been- I’m not very well rounded, but I’ve just wanted to do a few things well. That’s not necessarily a good trait, but I think what success I’ve had as a writer is because of that. That I’ve been able to focus pretty much on - my family - has obviously been more important, but after that, it’s writing. DJ: Was there anything that you decided right at the beginning that you were going to try and show people through your writing? RR: I think just that the people in Appalachia, there were differences, but ultimately they’re humanity. RR 12 DJ: Has that changed any over the period that you’ve been writing? Are there more goals that you want to show through your writing? RR: I think what I’ve tried to do ultimately, is write in a sense, give the reader a sense of the region through time. Because some of my work goes back to the Civil War, and stories about the Depression, stories about 50s. I’d like to think that I’ve created kind of like a quilt, where these different stories, novels, poems there all of one thing. DJ: Would you ever consider doing a modern day Appalachian story? RR: Oh I’m doing it. I’ve done it. I’ve done it in my short stories, but this new novel’s set contemporary, right now. 2014-15 DJ: If you could choose one main thing in the Appalachian culture to write about, what would you think it would be? RR: I don’t know. To me it’s all interconnected. I think my goal is just that I would like when someone looks at my work now, six novels, six collections of stories, four books of poems, that they would feel like they’ve really gone into this place, know this place, and what it feels like to see how the sun comes over the mountains. What a stream looks like when the sun hits the mica. What a winter would feel like, what it’d feel like to be in a cove. To hear the language, to know the food, to know the music, and all those things. DJ: Are there any places besides your grandma’s farm that have any really big impact the settings of your stories? RR: Yeah, all around Boone, and Madison County. These are all places where my family’s lived. There are different places. I’ll just set a story in a place I know say, outside of Boone, or a place I know in Madison County, or a place I know in Leicester, or a place I know around here. I’ve set stories around here, right on the Tuck, right out here. DJ: So, what’s your personal opinion on the Appalachian way of life? RR: I think what I’ve seen in my own family, what I admire is perseverance. These are people who, once again you have to be careful with generalizations, but I think people who have persevered in a very tough environment, and very often having less. And I admire their self-reliance. I think those are traits that you still see here in a lot of people. DJ: After writing as much as you have about all the different places, is there something specific that you notice changes in the way that you write about each different place? RR: Well, I notice how it changes, how the world has changed. When I write, the influx of… you have second owners now, things like that, they certainly shifted. I just kind of keep… To me, it’s almost like I’m drilling for water, I just keep going deeper and deeper and the stories keep coming. As long as they come… I mean, in the last two months I’ve written three short stories. Sometimes I just wonder, “Well, I have not mined it all and yet something always seems to come back.” Another story comes, and I just kind of keep hoping that happens. Maybe that’s a good way just to end this. That to me, is maybe the best thing I can say. Do you got one final question? RR 13 DJ: Unless there’s anything else you want to add? RR: No, those were great questions, and impressive interview. DJ: Thank you. I had fun interviewing you.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Ron Rash is interviewed by a Smoky Mountain High School student as a part of Mountain People, Mountain Lives: A Student Led Oral History Project. Rash, a local nationally known writer, talks about how growing up in Appalachia and living on his grandmother’s farm during the summer influenced his writing.

-