Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2683)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (7)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- 1700s (1)

- 1860s (1)

- 1890s (1)

- 1900s (2)

- 1920s (2)

- 1930s (5)

- 1940s (12)

- 1950s (19)

- 1960s (35)

- 1970s (31)

- 1980s (16)

- 1990s (10)

- 2000s (20)

- 2010s (24)

- 2020s (4)

- 1600s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 1910s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (15)

- Asheville (N.C.) (11)

- Avery County (N.C.) (1)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (55)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (17)

- Clay County (N.C.) (2)

- Graham County (N.C.) (15)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (40)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (5)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (131)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (1)

- Macon County (N.C.) (17)

- Madison County (N.C.) (4)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (1)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (5)

- Polk County (N.C.) (3)

- Qualla Boundary (6)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (1)

- Swain County (N.C.) (30)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (1)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (3)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Interviews (314)

- Manuscripts (documents) (3)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (4)

- Sound Recordings (308)

- Transcripts (216)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newsletters (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Publications (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- African Americans (97)

- Artisans (5)

- Cherokee pottery (1)

- Cherokee women (1)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (4)

- Education (3)

- Floods (13)

- Folk music (3)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Hunting (1)

- Mines and mineral resources (2)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (2)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (2)

- Storytelling (3)

- World War, 1939-1945 (3)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Sound (308)

- StillImage (4)

- Text (219)

- MovingImage (0)

Interview with Frederick Miller

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

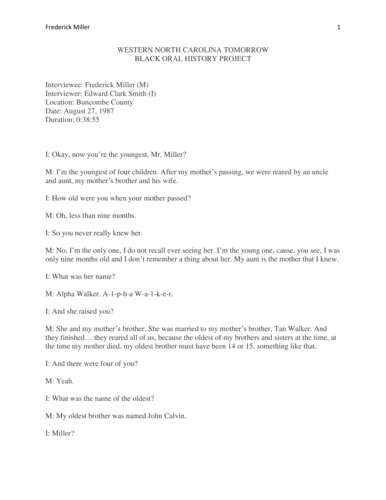

Frederick Miller 1 WESTERN NORTH CAROLINA TOMORROW BLACK ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Interviewee: Frederick Miller (M) Interviewer: Edward Clark Smith (I) Location: Buncombe County Date: August 27, 1987 Duration: 0:38:55 I: Okay, now you’re the youngest, Mr. Miller? M: I’m the youngest of four children. After my mother’s passing, we were reared by an uncle and aunt, my mother’s brother and his wife. I: How old were you when your mother passed? M: Oh, less than nine months. I: So you never really knew her. M: No, I’m the only one, I do not recall ever seeing her. I’m the young one, cause, you see, I was only nine months old and I don’t remember a thing about her. My aunt is the mother that I knew. I: What was her name? M: Alpha Walker. A-1-p-h-a W-a-1-k-e-r. I: And she raised you? M: She and my mother’s brother. She was married to my mother’s brother, Tan Walker. And they finished… they reared all of us, because the oldest of my brothers and sisters at the time, at the time my mother died, my oldest brother must have been 14 or 15, something like that. I: And there were four of you? M: Yeah. I: What was the name of the oldest? M: My oldest brother was named John Calvin. I: Miller? Frederick Miller 2 M: Yeah. I: And who was next? M: I had a sister, I believe, so they tell me, between, whose name was, ah-h-h well, really, now, I don’t recall this girl’s name, because she died, as they said, deceased sister next to him. And then a brother next to that whose name was Broadus [Brautis]. And another sister who is living now, Miss Nola Miller. I: Nola Miller? M: Her name is Nola Miller Knuckles now. I’m sure this is not what he said to fill the above blank, but that was so faint it might not have been a name at all. I: And then you. Frederick. M: Yeah. I: Mr. Miller, do you recall or have you ever heard anybody tell how your family got its name, Miller? M: Well, you must know that from the time of slave time that all slaves’ names, their African names, were changed and they took the surname of their masters. If your master was a Smith, why, his slaves become Smith and that name came on down from one generation to the other. I: Do you recall ever hearing your aunt and uncle that raised you talk your mom and dad? M: My father, the only thing I knew about him was that he died a few months before I was born, and Mother evidently was pregnant with me when he died. But I think he wasn’t the choice of the… he wasn’t the person that my family liked, anyway, but my mother had been married to him a long time and had several children. But, I mean even before these others that I gave you the name of, I don’t know, but I understand there were several children who had died. Survived, the four that I know, you see what I mean? And I don't think he was exactly the favorite of her family, so when he finally died, and I guess they blessed the time that he died, because he died before, as I said, and my uncle and aunt finished rearing us after my mother died. I was the baby. My sister who's next to me must have been six years old when I was born. I: You were born March the 10th, 1917, in Greenwood, South Carolina? M: Yeah, I think that's right. I: Growing up, what do you remember growing up? M: Oh, a very happy time. Very jolly time. Not even realizing that my parents had died or anything. It's just one of those things like I didn't know anything about, just hear somebody say Frederick Miller 3 it. We had a beautiful growing up time. A beautiful growing up time. Our parents were very, very nice to us. They were educationally inclined, and they wanted the best for their children. My aunt had a son by her first marriage. My uncle had two children by a former marriage. When he married the lady that reared me, he had two children and she had one. So when they brought us all together after my mother died, they inherited four more children. I: They had a family then, didn't they? M: And they had a family. I: What did they do for a living? M: They were farmers. I: So you came up on a farm? M: Well, partly, I've been in Asheville. My parents moved to Asheville back when I was twelve, so… I: What year was that when you came to Asheville? M: Oh, that I don't recall exactly right now, but I came to Asheville when I was twelve years old. I: What was Asheville like as you recall it coming here? M: Well, it was a great change from what it is now. The downtown section has changed greatly, and most of the streets have changed, the attitudes of the people have changed. I: How have the attitudes changed? M: Um, well, the Whites are more liberal and most of the Blacks that I knew at that time, a large number of them, particularly all of the, practically all of the elderlies are dead. Then, what I would remember about the young folks is just about this generation that you know is going by what you remember about your parents. Just about the same thing. I: What were conditions like for black people in Asheville when you first came? Were they segregated? M: Oh, yes, Asheville was segregated, greatly segregated, throughout the sixties, you know. I: What kind of…when you came at twelve, did you go to school? M: Yeah. I: What school did you go to? Frederick Miller 4 M: I went to Hill Street, and I graduated from Stephens-Lee. I: And that was… the school system was segregated then, wasn't it? M: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. You went to… we had Hill Street School, we had Livingston Street School, we had, uh, Stephens-Lee High. Later Mountain Street was built, and I believe there was a school in West Asheville and a little two-room school in South Asheville. They were for all Blacks. In the high school, we had… could have had more, but I think maybe it wasn't called for. I think our curriculum was a little less than the other folk, and we didn't have some of the offerings that they had. because as I remember we did not have the paid music teacher in the high school, we did not have a paid coach at the time I graduated in 1935. We had a coach, and we had musicians, but that was extracurricular activities for them. I was in the Stephens-Lee Glee Club. I also was the… participated in anything musical that they had. In fact, I was one of the honor students who graduated from Stephens-Lee with honors. I won the state contest in musical activities, particularly vocal singing, twice I won the first prize, for the bass section soloist. I: Do you still sing now? M: Oh, yeah. Yes, yes, I’m coming to that. I graduated from Tuskegee Institute, that’s Tuskegee University. I was in the Tuskegee Choir, the famous Tuskegee Choir. I was lucky enough to make the concert choir in my freshman year, which was not usual, under Mr. William L. Dawson. Mr. Dawson is still… he lives at Tuskegee Institute now, he lives in Tuskegee City now. I think he probably is 85, 82 years old. I was trained in the choir work there under him and locally here in Asheville. I had a great deal of musical training, private and in school. I’m a pianist. I took piano music, I took vocal music, but all of that was private here in Asheville. My parents were poor, but I was able to work and do what I wanted to do, to pay for it myself. I: When you came to Asheville, when you came with the people who raised you, what did they do for a living in Asheville? M: Well, my father did what they call construction, my uncle rather, did what they call construction work. My mother was a domestic. My sister did domestic work, she and the other girl, my uncle’s daughter, who we called a sister. And they finally worked at Oteen, finally worked at Oteen and, I believe, before either one of them married, they had worked at Oteen, in pretty good shape. I: What did black people, when you were probably 18, 19, 20 years old, what did we do here in Asheville for entertainment? M: Now, there were several clubs we had, as I remember, there were dances which were very greatly enjoyed, and that's just about the end of the whole thing. Most of the people…that's about all we had then. Went to the theater, going to the movie was very popular in those days. There wasn't much to offer as it is now. I get a surprise when I hear people talk about how the young folks are now. The young folks didn't have as much to attract them, as much to go to as it is Frederick Miller 5 available now, and, of course, there was a lot of church activity related around the church because young people didn't have anything else much to do but go to church. I: Is the church any different now than it was back when you were? M: Oh, indeed so. I: How is it different? M: Well, I would say the church is different, very noticeably so, in attitude and commitment, now. The ministers are different. At least we view ‘em as being different. I think they're different. Maybe they're supposed to be. I don't think… If I had to make an opinion about it, I'd say the ministers are not as devoted as they once were, and I would say that the people who say they make up the supervision of the church are not as devoted as they were, and I think the church has become a little too liberal in what it accepts. I do. They have become a little bit too liberal and the church has lost some of its momentum because of that. That’s what I think about it. But we're not perfect, and I believe we make too many excuses for ourselves and for others. I: When you came to Asheville and it was segregated, because it was probably segregated in Greenwood, too M: Oh, yes. I: How did you feel about? M: Well, now, at 12 years old you don't worry too much about… you just take things mostly like it is, and you must realize at that time the family had greater influence on the children and you didn't hear too much about certain things, because as they exist. And this was the norm of things. There wasn't much said about what was going on. Everybody accepted the situation as it was. When I said everybody, that's just it. So there was nothing to be said about it. Particularly, you didn't think that much about it. This was a way of life, and that’s all. As we would say, this is the Blacks and the Whites. As I said, most of the work that was done here, Asheville was greatly in the tourist orientated at that time and was a great. The climate was very good for people with tuberculosis. I: So a lot of them came for that reason. M: Yeah, there were a lot of people here who had come here for the health reason. It was a great different from what it is now. The mountains were not torn down and there were a lot of cabins built up on the mountain for tubercular people. One of our presidents had a son there, up on Sunset Mountain, Herbert Hoover, who was here for tuberculosis. Asheville was noted for its tuberculosis, and its hospitality, it was a good tourist place, too, 'cause the water was good, the air was good. I: It's a mess now, though, isn't it? Frederick Miller 6 M: Yeah. And Asheville wasn’t as accessible as it is now. You had to climb up the mountain to get here any way you could come, by rail or, at that time there wasn't so much thing as a bus running or you coming in a car. If anybody wanted to come to Asheville, they came on the train from Greenwood which was probably all day long. As I remember when we cane to Asheville we were on the train, it seemed to me, all day long. I: It was a long trip, wasn't it? M: Ye-e-e-s. And it was only-at that time it was only 105 miles, and it's shorter than that now. 'Course you get in a car now and fall down the mountain. In fact, you don't go to the mountain, you just get out. But it used to be awful high, and when you got here why it was altogether different from what it is now. It seemed like another world, another place, of course. I: With the interstate highways M: Oh, yes, it's not the same by any means. I: Mr. Miller, do you remember any customs that black people had that have kind of gotten lost now? M: Customs, like what? I: Either cultural or heritage or religious customs that we used to follow that you may remember that we don't follow now. M: Well, ah-h-h. Religious. We don't go to church near as well as we used to go in Asheville the Blacks don't attend church as well. Nearly half as well as they used to attend, as religious. The Blacks accept more things in the religious culture than they used to accept. I: What were some of the things that used to the church didn't accept? M: That they didn't accept? I: Um-hm. M: Well, adultery. The biggest thing that they accept, what I'm trying to make the difference in, I've known the time when the church would not go along any way with anything on that line. If there's somebody in the church who became, as we say, who decided to shack, why, they put them outside the church, which I believe they were a little bit on the wrong side to do it. If a girl had a baby unmarried, she was what they call turned out of the church. I don't think you can turn anybody out of the church. We are taught that you can't turn anyone out of the church. You're not supposed to do it, but that was the way it was. In fact, they were very what they call character conscious in the church, which they are not now. Anything is accepted in church now. 'Course it's been going on all the time, but they accept anything now in church, because I believe that we have people in church who're in higher places who are adulteresses. I keep hearing, which I have Frederick Miller 7 nothing to say about it because people do as they want to do. We're all liberal minded now and we understand that we don't judge people. I: What was the leadership like in the black community as you grew up? Do you remember anybody that was against segregation or tried to help? M: No. The people that we call the leaders always looked out for what we would say, were particularly thinking of themselves and the way things are. It was better for them because as the Blacks… as I recall there were two or three families then. The other Blacks didn't get anywhere unless those two or three families, they were consulted whether you should take this, do this, or whether somebody else should do it. The power that be was always the other folk but they called on two or three families to see what you thought about this individual. And you thought was what it was. I: Well, you know, it's not much different. M: Great difference. You might think it's not because you didn't know how it was. If you had known how it was, you would say that you're in a different ball game altogether. I know how it was. I had a beautiful tine all through high school because I had something the school people wanted. I had something that some of the folks in school wanted. They wanted the best, and I was supposed to be a talented person, and I got along nicely in school, wherein maybe I wouldn’t have had I not been what they thought talented in something, had something that they needed. I hope you get the gist. I: Um-hm. M: Hill Street School was headed by Professor J. W. Michael, Stephens-Lee School was headed by Mr. Lee. And they were the school system as far as the Blacks were concerned. Professor Michael and Mr. Lee. Now, that’s just all there was to it. I: So anything anybody else… M: Dr. Miller and Dr. Walker, particularly Dr. Walker, Professor Lee… I've said Dr. Miller, and Mr. Michael. Well, the white community wasn't going to do anything till they consulted them. And that isn't exactly how it is now. I: How do you think it's changed? In your opinion, were different things good or bad? M: Well, a lot of people have died, and the younger people as they come along did not stand for it, and there've been a lot of challenges. And, of course, as things have changed the community, the white community is not like it was. 'Cause the Blacks were not going to stand for it. We have a lot of people who speak their mind now and who really have the white community really shaking in their pants around. We didn't have people like Wilhelmina and some other Blacks who speak for the black community. As I said a while ago, if somebody wanted to talk, they always made sure they talked like the people wanted them to talk, because it was better for them. That's. Frederick Miller 8 I: So if you didn't talk… M: You wouldn't expect Mr. Lee to say if something was going to change the White peoples’ attitudes about him. You just wasn't qualified to do anything unless some of these people that I just called… I: Endorsed you. M: Endorsed you. And that's going… that hasn't been so long… they stopped because some of the people died. And when they died, they were replaced by others and, up until, you probably went, I know you went to Hill Street School under Miss Lee, the late Miss Rita Lee controlled what was going on practically all the time, practically up until she lost her health. When anything happened, they would ask her opinion. She didn't have as much input on it as she once had had because, as I said, Dr. Walker was gone, Mr. Lee was gone, Dr. Michael was gone, Professor Michael was gone. And the other folks didn't have those folks to call and say what do you think about Smith. "Miss. Lee, he's asked for a job. What do you think about him?" She might say, "Well, no. I don't want him. I don't think he'll do. I think you might get somebody. I got another man, another person, and that's it. I: You? M: 'Cause Miss Lee recommended him. We've asked Miss Lee's opinion and she gave it. Didn't anybody teach. You might interview when you, if you interview Henry Young out there, he probably would tell you the same thing. Didn't anybody teach at Stephens-Lee up till the time, till 1934, that Mr. Lee didn't endorse. Naturally, he was the principal. But, what I meant, he hired the teachers. I: Um-hm. M: 'Cause you just wasn't gonna get them if Mr. Lee wanted… no matter how well you were qualified because Mr. Lee was a very good man, but he wasn't the best formally educated man that you had. In fact, he had teachers teaching there with master's degrees, and I don't think Mr. Lee even assumed to be a bachelor's degree till after he was at Stephens-Lee a long time. I think he was one of those teachers that they said came out of a normal school. 'Fact, I believe Mr. Lee graduated from Morristown. I: Somewhere in Tennessee? M: Morristown. I think. I don't know. I believe that's what… But he had two or three teachers with master's degrees that taught under him. But, he was the power that be. He had the power, you picked the word, he was the power that be, so that's it. He mighta not been the most capable person for principal, and I said in the beginning that there were things we could have had if he had asked the school board for it, but he didn't ask the school board for anything the school board didn't want us to have. Because as I came through high school, the white kids had typing all the time, and we didn't have it in our curriculum. Frederick Miller 9 I: Why don't we get back to you. Now, you were talented musically. M: Oh, yeah. I'm an organist. I: What were your ambitions? M: If my family had been wealthy, had had enough income, I would have majored in music at school, because I always wanted to be a musician, a professional musician. But I wasn't able to get it because that's one of the highest things we could have had, and my family wasn't able to finance it. So I did get a scholarship and I went to Tuskegee Institute. I took foods and nutrition there, and then I participated in anything musical that I could get into. In fact, I I: The music wasn't something that you could make a living at? M: Well, music was something you could make a living at, but, what I meant, I didn't have the, musical education is like law and doctor, it's one of the, and it still is, one of the most expensive professions you can embark upon is music and, oh, jurisprudence and medicine. Those are the highest. Engineering has come in now, but engineering is new in the line as far as we're concerned. But, if I could have had what I wanted, I would have majored in music, particularly voice. 'Cause I have more musical training than I have anything else although I have a degree, B.S. degree and a little bit over in something else, but I've had more training, more musical contact than I have anything else because I had it before I finished high school and I had it through high school and I had it in college on, you know, just what you pick up and what your contact is. If you want to you can pick up a whole lot if you're exposed to it and you want it. You know what I mean? I: Um-hm. M: You can pick up a whole lot, if you want something and you're exposed to it. I: In your life, what are the historic events that you remember most, that stand out in your mind. Things that happened like floods or wars or…? M: Well, there hasn't been anything particularly that I can… anything much. I: The Depression? M: Well, the Depression, I hear people talk about it but there was only… as far as Asheville is concerned, we wasn't particularly… the majority of the black people in Asheville during the Depression, it didn't hurt them so much because we had little. We was getting along with a little bit and we still… I don't think my parents ever missed a day's work the whole thing through. Now, a lot of people, some of those people whose names I have called, I understand, had some difficulties about the Depression because they possibly had something. But the majority of the Negroes didn't have anything and life sort of rolled on as it was with us. Frederick Miller 10 I: Did [inaudible]? M: Not too much. That's why I can understand now when I hear over the TV or hear some black people say to the black people since the Reagan administration, “What you despairing about? You've made it before, and you made it on your own. Don’t worry too much about what Reagan has done. Let's get together and do it ourselves like we always done." We don't have to worry. We survive. The Blacks have not been as you see then very long, 'cause you're young. You came along when things…oh, the sun was shining. But some of us come along when… I: It was raining? M: It was quite different, when it was quite different. And, if you think about it, we don't have to worry too much. Now, you must remember that the Blacks have always sent their children to college some way or another. The mothers worked out for white people making five or six dollars a week, and they sent their children to college. They bought homes. Some of the men worked on the railroad. Some worked at Oteen. Some did public work. And they bought their homes. They didn't nobody come and give 'em those places. People bought their homes. I don't know how they did it. They sent their children to school, and they had things. We've always had nice homes… comfortable homes. We haven't always had three or four TV's in the house, and we haven't always had three or four cars in the yard. We might have had one car. If it was necessary to have it to go to work we might have had one car. But otherwise we walked and caught the bus and went where we wanted to go. And we didn't waste a lot of food like we waste now. People worked harder, served the Lord better than they do, and he provided for us. But we have a whole lot now we can't hardly make it, just can't hardly make it. And still we just got a whole lot. Now, the Whites committed suicide, they did everything during the Depression. I: They lost their money. M: But most black people kept their equilibrium. I don't remember any excitement among Blacks particularly. Why, the schools, the teachers were not making more than $85 a month. I: So, then, they didn't really have any money in the banks to lose. M: No, unless it was somebody like… Now, Mr. Lee had a lot of property, he had a lot of rented property. Practically all of Velvet Street belonged to him. Practically every house on Broad-Velvet Street belonged to Professor Lee, and all down below Mount Zion Baptist Church, a whole lot of that property belonged to Mr. Lee. Okay. Now, I 'm going to ask you, uh... I: What I'm hearing is that it was the white man who oppressed black people, but he did it by using… M: Other Blacks. I: Other black people. Frederick Miller 11 M: Some did it directly, but, now, there's always been a sham of this type of black leadership and black this. What I'm coming after and what I've tried to say to you, that the Blacks didn't get anywhere unless the black leaders, and that's not good, the black leaders appointed you. It all come from them, but before you got there, not on your own merit, you got there because the black leaders said that you were supposed to be there. Now, you could have been a son. You could have been Mr. Jones's son. Mr. Jones could have been one of the, as the white folks call them, a black leader, and you could have been Mr. Jones son. Well, all Mr. Jones had to do was tell 'em he wanted you to do this or that, and that's what you got. I: What do you think of leadership now? M: Oh, the black leadership? What you mean, black leadership or leadership? I: We don't have it, because, you see, we integrated, and the most of the thing is now, it's become more political than anything else. And the Blacks are usually getting part of what they want because we don't have that system anymore. You mostly got to be prepared for what you get or you ain't gonna get it. Because if I think you're not prepared I'm not… there's nobody to shield you. You're going to have to stand up on your own merits now. Because you're not only competing with the Blacks, you're competing with the Whites, and you got to be good or a little better. I’m trying to say that it's not the sane. It's harder for you to get where you want to go to now, just as hard, but it's in a different way. That time was that a lot of people got where they wanted to go and they wasn't supposed to be there in the first place. They got there because somebody else said, ''You ought to be there." I: Um-hm. And some M: And I have given you the names of the people who were what the, as far as the white people were concerned, Dr. L. O. Miller, Quentin Miller's daddy, came from an outstanding Miller family, bricklayers in this community. His daddy and all of 'em built, and every brick building you see here in Asheville now that hasn't been torn down was come by through the Miller family. Anybody can tell you. And then they were outstanding, the Millers, Old Man Jim Miller, who was the patriarch of the Miller family. Alf Wilson, he's dead now, who used to run the Wilson Undertaker; he founded the Wilson Undertaker in the Wilson Building down there. And, us, professor Michael, Professor Michael was a well-educated man but he was considered one of the leaders. Mr. Lee. Now, Mr. Lee was the second husband of a very famous woman who had taught at another school here. I think they said that his first wife helped to found the school system here for Blacks, way back before the turn of the century. And there had been a disastrous fire here at the school, right up there where Stephens-Lee gym is now that was called Catholic Hill School… a disastrous fire, where several people, children and teachers, lost their lives. And this lady was teaching there; she was the sister to Dr. Walker, Dr. Holt's uncle or aunt, rather. And it seems that, when she died, there was another man there who was principal of the school whose name was Stephens. And after she and they built the high school for the Blacks back in the twenties, I understand, I don't remember this, but in the early twenties, they said, we had a END OF TAPE

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Frederick Miller is interviewed by Edward Clark Smith on August 27, 1987 as a part of the Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project. Born in 1917, Miller lost his parents at an early age and was raised by his aunt and uncle. Miller moved to Asheville when he was 12 and attended Hill Street School and then Stephens-Lee where he won first prize in a state musical contest for vocals. Smith graduated from Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Miller describes the inner politics of the black community that existed as he was growing up and how that has changed.

-