Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (26)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1388)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (1794)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2399)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1917)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (161)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1671)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (233)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (510)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3522)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4692)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (25)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (12)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (211)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (981)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2113)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (247)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (73)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (184)

- Envelopes (73)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (812)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (619)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (5835)

- Newsletters (1285)

- Newspapers (2)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (7)

- Portraits (1960)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (151)

- Publications (documents) (2237)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (15)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Vitreographs (129)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (282)

- Cataloochee History Project (65)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1407)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1744)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (167)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (110)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (1830)

- Dams (103)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (921)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (38)

- Landscape photography (10)

- Logging (103)

- Maps (84)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (71)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (245)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

Interview with David Reeves

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

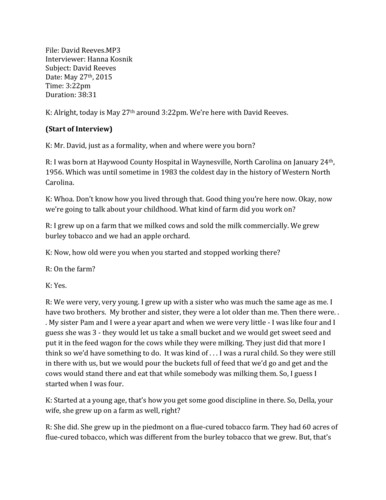

File: David Reeves.MP3 Interviewer: Hanna Kosnik Subject: David Reeves Date: May 27th, 2015 Time: 3:22pm Duration: 38:31 K: Alright, today is May 27th around 3:22pm. We’re here with David Reeves. (Start of Interview) K: Mr. David, just as a formality, when and where were you born? R: I was born at Haywood County Hospital in Waynesville, North Carolina on January 24th, 1956. Which was until sometime in 1983 the coldest day in the history of Western North Carolina. K: Whoa. Don’t know how you lived through that. Good thing you’re here now. Okay, now we’re going to talk about your childhood. What kind of farm did you work on? R: I grew up on a farm that we milked cows and sold the milk commercially. We grew burley tobacco and we had an apple orchard. K: Now, how old were you when you started and stopped working there? R: On the farm? K: Yes. R: We were very, very young. I grew up with a sister who was much the same age as me. I have two brothers. My brother and sister, they were a lot older than me. Then there were. . . My sister Pam and I were a year apart and when we were very little - I was like four and I guess she was 3 - they would let us take a small bucket and we would get sweet seed and put it in the feed wagon for the cows while they were milking. They just did that more I think so we’d have something to do. It was kind of . . . I was a rural child. So they were still in there with us, but we would pour the buckets full of feed that we’d go and get and the cows would stand there and eat that while somebody was milking them. So, I guess I started when I was four. K: Started at a young age, that’s how you get some good discipline in there. So, Della, your wife, she grew up on a farm as well, right? R: She did. She grew up in the piedmont on a flue-cured tobacco farm. They had 60 acres of flue-cured tobacco, which was different from the burley tobacco that we grew. But, that’s how we met. We talked about tobacco and how we both really didn’t like it very much. But, we’d gone through college, both of us, growing and selling tobacco. K: So, you’re saying there are different types of tobacco. How was her farming experience different from yours in that perspective? R: Our farm was much smaller than the farm she grew up on. Our farm supplemented our income, we milked 30 cows every day and we sold apples and we sold the small plot of tobacco we had. But my mother worked in a restaurant. She ran a small restaurant and my dad managed a dairy, a bottling plant. He worked for Pet Dairy. So the farm I grew up on was a lot smaller than her farm. Her family, they were only farmers, so they had - they took a lot more risk than we did. They grew more tobacco. K: So they were more commercialized. R: Yes. K: Okay. R: And flue-cured tobacco was a lot harder than burley tobacco. That was kind of a surprise to me. K: Well every kind of tobacco is hard tobacco right? R: It’s a stinky nasty habit and I’m sorry anybody has it. But, I was glad for the experience. K: That’s good. R: We learned to grow things and we still love to grow things. K: Okay. So, you said you’re from Haywood County. How long did your family lived in Haywood County? R: My ancestors moved to Haywood and Madison County, which is the county beside Haywood, before it was even legal to live there. They moved there in the very early 1800s and hadn’t really been that opened up to people settling there until the 1820s. The places that they moved to . . . They were typical southern Appalachian people and they moved from mostly Scotland. They moved from mostly Scotland to first Pennsylvania and to Virginia. But what they just did was they moved further and further down the Appalachian chain until they finally got to a place where nobody would bother them. A whole class of people did that. Southern Appalachia people did that. And that’s why we talk like we do. So it’s kind of an isolated dialect. K: Right. Okay, and what kind of role did they serve in your community nowadays? R: I’m not sure I understand the question. K: I’m sorry. What kind of role did they serve in the community? R: My parents? K: Your family. Yeah. R: My ancestors? K: Either one. R: My great, great grandparents, all of them, were farmers, subsistence farmers, which meant that they grew and made everything that they ate, like everyone else did. They fought in the Civil War. My great, great grandparents did. My great grandparents were farmers as well. They were more commercial farmers, because they had this apple orchard that they grew and shipped apples to different places. In fact, they shipped apples to the army during World War One. K: That’s cool. R: My grandfather was a dairy farmer and a professional baseball player briefly. He played for a professional team in Knoxville, Tennessee. I’m sorry I don’t remember the name of it. And my dad, when he left the navy after World War Two, came back to work on the dairy farm and just decided that it wasn’t going to be able to produce enough to support his father and mother and his young family. So, he got a job working for the dairy that came to pick up the milk and turned out he liked it a lot. So, my dad worked for Pet Dairy for 49 years. K: That’s a long time. R: Yeah. He started as a truck driver and ended as a manager of the bottling plant. So, he did, I guess, the whole thing. And my dad is still alive. He’s 90 years old and still lives on the farm. K: Man. That’s a pretty good deal. R: Yea, he’s a good guy. My mother was born in Washington State during the Depression. No, just right before the Depression, the Great Depression. My grandfather was a builder. I was born on his birthday. Then, when the Depression hit, they moved back here. So she grew up here, even though she was born far away. And she worked in restaurants as a young person. Then, during World War Two, while my dad was gone for the Navy, she worked in an aircraft factory. [She] pulled wiring harnesses through aircraft, because she was little, so she could crawl through the fuselage and places that nobody else could get. So she pulled these wiring harnesses through to build these airplanes. Then later worked as an accountant, because she had good accounting skills. And after the war was over, she moved back and ran a restaurant her entire life. In fact, she worked until a month before she died. K: Oh my goodness. Very successful, sounds like it. R: She liked what she did. K: Okay, let’s move on. Now, we’ve always wondered this while we were researching you. What was your first calling, an EMT or a minister? R: Well actually I went to college to be an English teacher or a writer. And when I got my degrees, I discovered very quickly that I was not a very good writer. It wasn’t any fun. I didn’t enjoy doing that. Then, I really wasn’t cut out to be a public school teacher. You need a different kind of nature and character- and I really admire and respect public school teachers, and so I needed not to do that. So as I was kind of like looking at the possibilities. One of my professors at the college I attended said you’ve taken all these courses in Religion, why’d you do that? And I didn’t really think that much about it, I just thought it was interesting. And we talked about it and that person said maybe you should consider being a minister and I’d always been to church, but I had not given much thought to that. I had not experienced what I had been sort of told was the call. And actually, never did get that. But my professor, who at that time was both a Ph.D. and something or other, but also a United Methodist Minister, he said well sometimes that call is more subtle than maybe what you’ve been led to believe. So, I thought about it for a while and applied to Duke Divinity School, to the seminary there at Duke, and went there. And I graduated in 1982. Went to work as a pastor of a church in Maggie Valley in 1982. And then in 1983, while I was driving to town I saw a wreck in front of me. I ran out in the road, I don’t even remember why. She ran out in the road and she hit something and when I got stopped, she was injured and so I took a t-shirt and put it on the place on her head that was bleeding and then it occurred to me like you don’t know how to do anything. I mean like I had no expertise at all in first aid or any of those things. So, I signed up at the community college for a first aid course and the first aid course didn’t make, so they called me and said you could take an EMT course and I didn’t even know what that was. So, in 1983, I took a basic emergency medical technicians course and it was interesting, really interesting. I enjoyed it, I enjoyed the science of it and I’d never enjoyed that before. So very shortly after, when I finished that little course, I signed up for the paramedics’ school. And the paramedics’ school is a three year course, it’s like a college degree. K: Right. R: So I went for the next three years. I went to school at night until I finished the paramedic certificate and that was in 1986, I guess. And in 1986 I went to work part-time as a paramedic for the county EMS. And I worked until 2007 as a paramedic, I worked 21 years, I guess. K: Here in Jackson County? R: I worked in Haywood County and for Mission Hospital, but mostly for Haywood County. I worked for Jackson County as well. I worked for Harris Hospital for Med West. K: That’s pretty cool. R: So I was a preacher first, but I could’ve have just said that. Sorry. K: As a paramedic you were in there for a good 20 years, would you say? Now how did the field change, did you see drastic changes or changes over time? What kind of changes did you see? R: I had the good fortune of always being a part of a critical care provider, which meant that we were able to like operate at the highest level of care that anybody did in the country, which was what was really neat. We gave a lot of medicine. We did a lot of surgical interventions like decompressed chests and trauma patients. We intubated patients who had difficulty breathing. So, the things that we did were complicated and sophisticated and dangerous. But, you just had to be right. That was your obligation, was to make sure that you didn’t make a mistake or do the wrong thing. So, we did those things from like - for as long as I can remember. We provided a high level of paramedic care. The big changes that I noticed over the years were the technology got a lot more sophisticated which allowed the equipment to get much smaller, which meant that you were able to get at it a lot faster. The medications changed a lot. The medications got simpler. When I first started you might give like 7 or 8 different medications if you were working a cardiac arrest. By the time I finished you might give 3 and you didn’t have so much to keep up with. So everything, in my experience - the care improved dramatically over those twenty years, just because it got a lot faster and a lot easier. Then with the advent of the helicopter, that added another layer of support where if you had multiple causalities or you had somebody that really needed surgical intervention right then, then you could get them to that next level of care a lot faster. If you get the helicopter in there, that was good. So, my experience as a paramedic was almost entirely positive. I loved doing it, people loved seeing it. Pretty good isn’t it? And it was interesting. Like it was never the same thing, ever. Just when you thought you’d seen everything in the world, you go like “holy cow, wouldn’t have thought that!” So, that was good. K: If you could pick one, what would be your most interesting case? R: Well, there were maybe two. They’re not long stories, so . . . We actually went down Interstate 40 to one of the tunnels and what had happened was a an elderly gentlemen had gone into the tunnel on a bright, sunny day like this and he just was old and he had on his sunglasses and he couldn’t see. So when he pulled into the tunnel, even though the tunnel was lit, he couldn’t see very well and he stopped and when he stopped on Interstate 40 in the middle of that dark tunnel, of course, the truck behind him ran over him. I mean, just ran over him and just wadded the car up under. It was a small car. So, when we got there, they had already told us that it was a fatality. The highway patrol said that they believed it was a fatality. They don’t say that on the radio, they call you on the phone, so that everybody didn’t hear it. So we were kind of set up to do this recovery thing, which I really hate. Because there’s nothing you can do, because it’s sad and tragic. So, we got up there, we got in there, and it’s dark in the tunnel. Traffic is stopped. So we’re needing to work as fast as we can, because by now the traffic is backed up more than 10 miles. And so I go poking around this car and you can’t really tell it’s a car and it’s wadded up under this trailer. And I can see this side of the door, so I got like some frame of reference and I’m going to look for the body right here. And so I stick a tool in there and pry the door a little bit and when I do it opens, which truly surprised me. You know I was, because I didn’t think it ever would. So when I get the door pulled open, I’m looking in there with a flashlight because it’s all dark, we’re in a tunnel. K: Yeah. R: And I see this face. And I’m like oh crap. And well he didn’t look that bad and then all of a sudden he looks at me and goes “well hey!” And I was just amazed and he was completely trapped in this thing. I mean there’s no way to describe . . . There’s no - we don’t know where the rest of him is. We can only see his face. So, we start just as gently as we possibly can, we use some big jacks and we jack the trailer up a little bit off of him, so we can see. And when we jacked the trailer up off of him, somebody cuts very carefully the top of the car away from him and we pull that piece out. And then we cut the seat out from behind him and then once the seat comes loose, he just sits up. And the strangest thing about this is, we got him out of there and he didn’t have a scratch on him. None. Not even like… K: No broken arms? No broken… R: Nothing you’d put a Band-Aid on. K: Oh my goodness. R: Yea, that guy walked out of there. K: That’s unbelievable. R: It was just . . . And it was like . . . That was the greatest day ever [inaudible]. That one was a memorable call. Probably the most memorable call that I, I love that one just because it shouldn’t have happened, okay? And I love that job, because occasionally you get to see things that shouldn’t happen. Of course, the other part of that is occasionally you’ll see something that shouldn’t happen. Not long after that we went to a trailer park where a two year old boy had wandered out of his house while his mother was on the phone and to her defense, she only looked away a moment. K: That’s all it takes. R: He fell in a creek that was kind of rain swollen. Wasn’t a big creek, but he wasn’t very big. And it took us about 20 minutes to find him and they found him. I wasn’t there, but they found him up under a bridge pylon. And so when they handed him up to us, he was in cardiac arrest, grey and wet, covered in leaves and dirt and stuff. And we just assumed, you know, we knew this was going to end badly. We started CPR on him and did the things that we were supposed to do and both my partner and I were relatively new paramedics. We had like less than a year and I remember my partner looked at me and she said we’ll just trust the training. Do what we’re trained. So she did CPR and I intubated him and did the things that we had to do. We took him to the hospital, he never showed any sign of life at all. We left him at the hospital and they continued CPR on him for 50 minutes while they warmed him, because he was cold in that water. And when he got up to 95 degrees, they defibrillated him one time and the boy woke up. And that was the most. . . I regret that we weren’t there. We had gone on to the next call, whatever that was, but we came back to the hospital and they literally, the physicians - don’t tell your dad I said this - but the physicians, they don’t have much interest in like coming out to help you at the door. They’re busy doing other stuff. But all these doctors came running out of the ER and they’re going like “come here!” So we went in and the little boy was like sitting up, crying, I mean he was crying because he was in pain, because they had done some awful stuff to him, but like he was alive. He was fine. He’s like 25 years old now. K: Oh my goodness. R: So yeah, that’s a good day. I guess those would be my most - except for the alien abduction. K: Oh let’s go into that. R: We had an alien abduction one night. The cool thing about the job is you never know, you think you’ve seen it all. One night at two o’clock, we got a call from the dispatcher on the radio and they said we need you to go to a certain address and I said, “Okay, what’s the code?” And the code means what is it. Is it heart related or is it a gunshot wound or is it a stroke or a burn, you know, what is it? And he said on the radio, he said, “I’d rather not say.” And I thought that was kind of odd, you know. So, we went to the house that they sent us to and when we got there the police were all out in the yard and these two guys were like laying in the yard, face up, with their arms folded in over their chests. And I thought . . . I didn’t know what I was looking at. I thought “are they deceased?” And so I got out and I said “what you got?” And they were like, “just go.” So we went over and I spoke to one of the guys and he opened his eye and looked at me and closed his eye and he wouldn’t move and I said what is this and he said it’s an alien abduction. So, the story we got from the guys on the ground was that the aliens had come to them, landed in their yard, kidnapped them, put them on the spaceship, told them that they were going to take them on a ride on the spaceship, and they took them to Waterrock Knob which was like 10 miles away on the parkway. And one of them said to the aliens “why don’t you take us to space so we can be weightless” and they said “this is all the gas we have.” So, they brought them back and left them in the yard and told them to eat ant poison, which they did. And so I had these two, two highly intoxicated, I would guess, men who had taken ant poisoning, laying in the yard. And so we talked about like how we were going to get them in the ambulance, because they didn’t want to go and the cops were going to kind of like make them and I didn’t want to go there. So I went back to one of them and I said, “Have you ever heard of Obi-Wan Kenobi?” and the first one said no and the other one said, I can’t tell you what he said, but he said “yea” and I said “well I’m his son, so let’s go ride in the ship.” So we took them to the . . . Turns out ant poisoning is just boric acid so it’s just not dangerous to humans, so we could have left them in the yard, they’d have been fine. That was my only alien abduction. K: Don’t hear that story every day. R: No. K: Okay, now we’re going to focus on the church, Cullowhee United Methodist. What do you believe is your role, I mean your church’s role, in the community? R: What’s the role of this church in the community? K: Yes. R: Churches serve different functions I suppose. We have long sought to make this church kind of a center of activity in the community. By that I mean different groups come here to meet - boy scouts, girl scouts, cub scouts. It’s a place where people can come be safe. We have a day camp and a summer camp and preschool. It is a place where people can come and heal a little bit. We have narcotics anonymous and alcoholics anonymous meet here, so they come and navigate their lives. It’s also an important place where you can like come learn that Jesus story. We don’t teach a formula here. We tell the Jesus story, whichever one it happens to be that day. Pick one, it doesn’t matter. So, we try to share that story and demonstrate it by what we do. I mean, 10,000 loads of wood that you delivered yourself, you know. And sometimes the really sad places that we go to take that. And so what we try to do is demonstrate God’s love by doing things that matter, that help. That’s what we think that’s our role here, demonstrate the mind of Jesus. And the heart of Jesus. Is that enough? K: Yeah. R: Okay. K: It’s really good. So, very active church. Very supportive. R: It’s a busy church and it always has been. This church has always had, for as long as it’s been in existence, since over a hundred years, a really high sense of civic obligation. They want to be involved in reducing suffering, helping in some way. They did that long before I was born and I just had the good fortune to be a part of it now. K: Okay. Now, when you give sermons every Sunday, you pepper them with life stories of yourself. What makes you want to do that? What’s the larger message you’re trying to send through that way? R: Oh okay. Well first, I would hope that anyone would understand that why I tell a story like that is to illustrate a point. It doesn’t mean that it’s about me. It’s just an observation in some way. It’s a metaphor, you know. The lives people might picture in their heads so that later when they think about it then maybe they can make it their own. I’ve always enjoyed observing. I’ve always enjoyed watching when we played volleyball how if you played close to your mother, you paid attention to where your mother’s elbows were. If you played close to anybody else you didn’t have quite as much to worry about and so I just kind of enjoy watching what people do and I guess, for some reason, I have a memory of what people do. So stories, all Jesus stories will play out in real time somewhere. I mean, they are . . . The Bible is the greatest metaphor ever, because you don’t have to look very hard to say “hmm I know somebody like that crazy guy in the cemetery, I know him, he’s in my family” or “I go to school with him” or whatever. I know what it feels like to be alone or to have someone hate you for no good reason and so if you can share some story that people like or are familiar with, then maybe they can make that connection a little more easily. K: Right. I think you do that very well. R: You’re very kind, thank you. K: Okay. When and where did you and Della meet? R: Okay that’s an easy story. We both grew up on farms which meant that we both belonged to an organization called the 4H club. It was like boy scouts and girl scouts for country people. We both worked at a 4H summer camp, though at different times. We worked at the same 4H summer camp in Waynesville. She was a swimming and canoeing and something or another instructor a few years after I had left working there. And I had gone back to visit some of my friends, I was already in college then. And I drove a truck for Pet Dairy for my dad. I had gone back to visit some of my friends and when I drove through the yard at the camp I looked and saw this girl walking across the softball field carrying a five gallon bucket of blackberries. When I got out I just stopped and I spoke to her and she spoke to me and I said “who are the blackberries for?” and she said “I picked them because they’re going to make a pie for the kids” and I said “who would pick blackberries without someone paying them?” I guess I was making a joke and she looked at me serious as could be and said “You wouldn’t?” I was like what’s wrong with you? And she wasn’t very nice to me at all that year, so I just left her be. And then the next year I went out there to deliver a special order of ice cream or milk, I don’t remember, And she was there again working. She was then a sophomore at UNCG and I had just graduated from college. So, I thought this time I’ll not ask her an idiot question, I’ll ask her good questions. So we just talked about farming, because we both grew up on farms and then a few days after that we met, we took a canoe. I had an old beat up canoe and we came to Glenville and we rode around on the lake and swam in the lake. And then a couple of weeks after that the season was over - the 4H camping season. And so we sat on the front porch and we talked to each other and we talked about a lot of things and I said “I am very, very fond of you” and she said the same thing and we just talked about it and decided we’d just get married. So after we’d been not really even dating for three weeks, we decided to get married. And very shortly after that we did get married. We were going to wait until everybody was out of college. But then Ronald Reagan had won the election and I didn’t much want to be getting married when Ronald Reagan was president. You shouldn’t put that in there. So, we moved it up to December of 1980. So we got married December 28th, 1980. I guess we met in eighty. We met in seventy-nine, got married in eighty. K: Do you not want that Ronald Regan part in there? R: Oh you can put it in there if you want to. K: I mean if you don’t want to, we can strike it. R: It’s okay. I liked Reagan fine. Carter was my president. So, it’s okay. K: Well that’s a very cute story. So what brought you and Della to Jackson County? R: When I graduated from seminary, I was ordained an elder in the United Methodist Church, which is what they call it if you’re a preacher. Then you’re under appointment. It’s like being in the Navy, like your dad, only not as dangerous. When you’re under appointment, they decide where you go. And my first appointment was Maggie Valley and we went to Maggie Valley in 1982 and Della was a P.E. teacher and could not find work and it was a recession then. So, she came to Western and she got a degree in early childhood education and a master’s degree here and an education specialist degree here and went to work as a classroom teacher. And she taught mostly fourth grade for the 21 years we were in Maggie Valley. And while I was in Maggie Valley I was a full time pastor of two churches and I worked full time for the EMS, for Haywood EMS. We did that for twenty years. And then we really had been there long enough. I had kind of run out of things that - they’d heard everything I had to say. And so I put myself up for appointment again and this was one of the possibilities, and so I came here. Both of us had gone to Western and we loved it here, so we thought this would be pretty cool. K: What year did you move here? R: 2003. K: That’s pretty good. Now, since you’ve moved here, how has the community changed? R: The University is three times larger than it was when I got here. There literally were about 4500 students when we first came. They’ve built . . . In the last 12 years, they’ve built 125 million dollars’ worth of . . . The fine and performing arts center, 7 residence halls, all those up here and all those down there. The student center is new, the health science building across the way. The university is literally twice as large as it was when we got here. So it’s a lot busier. Still seems like a small community to a lot of people that I guess come from larger cities, but it’s a lot bigger and I think it enjoys a higher level of respect in sort of the educational community than it did for a long time. When we first came here it was mostly a teacher’s college and it still is, but now, you know… K: Nursing and all that stuff. R: Yeah. So, the university has changed a lot and I have gotten to teach here, which is a lot of fun. I’ve taught at Western for 11 years and so that’s kind of changed. Like students have changed a lot in the last 11 years. K: What do you teach here? R: I teach a course called responding to emergencies where people learn how to control bleeding and do CPR and treat poisons and take care of burn victims and whatever. It’s sort of a high level of basic first aid. K: Okay. Now on a very, very serious note. Did you ever, ever, ever, ever have an afro? R: An afro? K: Yes. R: No, but when I went away to college I had a pony tail, that was probably a foot long. K: Oh my goodness. R: And God looked down from Heaven and said “Hah let’s watch this.” So never had an afro, but had wild hair. Always curly haired. When I was in college during the 70’s, like, everybody had long hair, way longer than yours. K: So it wasn’t unusual that you had a pony tail? R: Everybody was like that. It just was a thing. It was a thing that everyone was going through. . The Vietnam War was getting over. Everybody’s kind of like crazy. And so, yeah, everybody had long hair. It was a lot of trouble, I remember. K: Well it is, let me tell you. R: Sorry. But never had an afro. K: Do you have anything else to add? R: I, more than most people, feel blessed for the opportunity to see the interesting things I’ve seen and to meet the interesting people I’ve met. And like, being part of people’s lives in that way. There are a lot of things I would maybe do a little differently, I don’t know that there’s very much I would change. K: Okay. Well, looks like we might be done here. R: Well, thank you for this wonderful interview. K: Thank you for allowing us to interview you. R: If you can make an essay out of that then you’re a better person than me.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

David Reeves is interviewed by a Smoky Mountain High School student as a part of Mountain People, Mountain Lives: A Student Led Oral History Project. Reeves, born in 1956, talks about growing up on a farm in Haywood County. He tells about the path that led him to become a minister and then an EMT. He tells his most memorable stories as a paramedic. He then talks about the role of the Cullowhee United Methodist Church in the community. He remembers how he and his wife met and how Western Carolina University has changed since he moved here in 2003.

-