Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2683)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (15)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- 1700s (1)

- 1860s (1)

- 1890s (1)

- 1900s (2)

- 1920s (2)

- 1930s (5)

- 1940s (12)

- 1950s (19)

- 1960s (35)

- 1970s (31)

- 1980s (16)

- 1990s (10)

- 2000s (20)

- 2010s (24)

- 2020s (4)

- 1600s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 1910s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (15)

- Asheville (N.C.) (11)

- Avery County (N.C.) (1)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (55)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (17)

- Clay County (N.C.) (2)

- Graham County (N.C.) (15)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (40)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (5)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (131)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (1)

- Macon County (N.C.) (17)

- Madison County (N.C.) (4)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (1)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (5)

- Polk County (N.C.) (3)

- Qualla Boundary (6)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (1)

- Swain County (N.C.) (30)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (1)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (3)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Interviews (314)

- Manuscripts (documents) (3)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (4)

- Sound Recordings (308)

- Transcripts (216)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newsletters (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Publications (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- African Americans (97)

- Artisans (5)

- Cherokee pottery (1)

- Cherokee women (1)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (4)

- Education (3)

- Floods (13)

- Folk music (3)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Hunting (1)

- Mines and mineral resources (2)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (2)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (2)

- Storytelling (3)

- World War, 1939-1945 (3)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Sound (308)

- StillImage (4)

- Text (219)

- MovingImage (0)

Interview with Clifford Ramsey Lovin

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

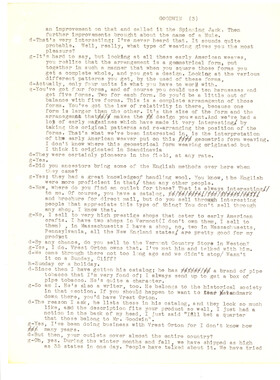

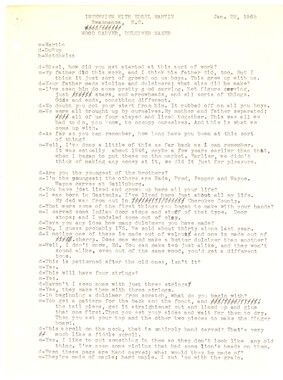

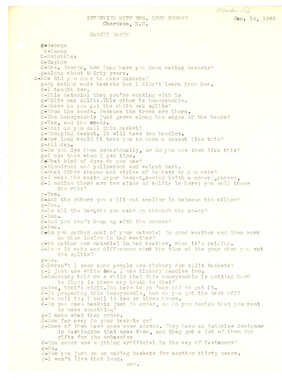

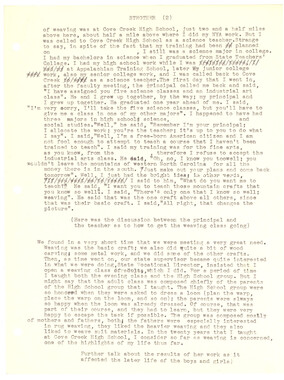

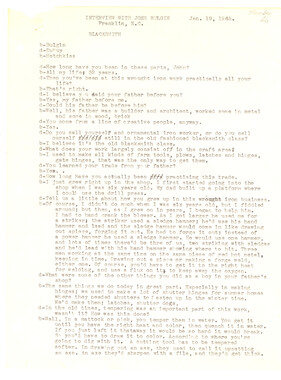

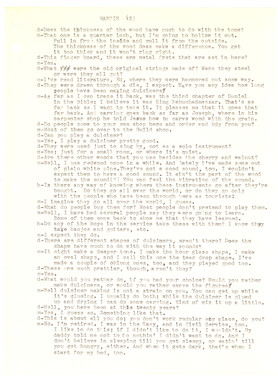

Clifford Lovin 1 Name of interviewer: Tony Wagoner Name of interviewee: Clifford Ramsey Lovin Date of interview: November 13, 2002 Length of interview: 1:15:23 Location of interview: Jackson County, NC START OF INTERVIEW (Audio clip A) Tony Wagoner: This is Tony Wagoner and I’m sitting here with Dr. Lovin, preparing to interview him for the professorship oral history project. Dr. Lovin, if you’ll confirm that you’re being taped. Clifford Lovin: I understand that. TW: And if you would state your name, please, sir. CL: Clifford Ramsay Lovin. TW: And we’ll get started. My first question is what university, or universities, did you attend as a student? CL: I graduated from Davidson College in 1957 and from University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, I received my Ph.D. in 1965. TW: So, you got your master’s degree, as well, from— CL: I did. TW: —the University of North Carolina. Did you teach anywhere prior to Western? CL: Yes, I taught two years at what was a junior college then in South Carolina, Central Western College, which was a church school. My father was a preacher and he wanted me to teach there, and I did. [Then I moved up here to be with my friend Max Williams.] [laughs] TW: Well, then, that kind of leads into my next question, but I kind of want to ask about the [inaudible] school that you taught at. How did that come about happening after you got out of Chapel Hill? You said your dad wanted you to teach there, but was there anything in particular that…? CL: I thought it was my duty. They wanted me to be a preacher and I wasn’t going to be a preacher and I thought this was one way I could satisfy my parents’ ambitions for me. And I did go there, but I just really couldn’t…it was much too…rigid, the organization. We had such things, we had revival meetings, we had to cut down on classes and couldn’t give tests and things like that. I just couldn’t…it wasn’t [inaudible] to teach. Clifford Lovin 2 TW: Well, I can certainly understand that. And that leads into my next question: what led you to the decision to teach at Western? Or, what motivated you to teach and stay? What gave you the comfort to stay? CL: Well, I knew after the first year that I didn’t really want to stay at Central, but I had agreed to stay there for two years when I came. And my best friend—the person who had become my best friend in graduate school—Max Williams, was teaching here. We visited him on several occasions and, actually, before the first year was over, the department head, [Craig Sossman], offered me a job here. And I told him I couldn’t come until that second year, and he said, well, he couldn’t promise me a job after that, but he relented and agreed to hire me. I said really, Max Williams was the primary reason. Our families were about the same age [inaudible]. He really believed this was an institution we could make a difference at, together. And we did. I was very happy to come. TW: At that point, what year was that? CL: 1966. TW: And at that point, did you feel Western was heading in the right direction academically and…because the state-wide universities of North Carolina are obviously a good system, but did you feel like Western was moving forward? CL: There was [no system here.] It was a separate institution in every way. Yes…I was not sophisticated about what was a good institution and what was not. This was a good job, it was a good place. I never had been here before I came to visit Max Williams, but I liked the area. I actually was born in [Inca, I never lived in the United States, I was born there]. So, I didn’t really think about the long-term future when I moved here. And we—this was a time of great growth in Western Carolina and we all just got caught up in it. And really—it was fun, we were really building something. We jumped from about 3,000 to 6,000 in about six years, I guess. And we were teaching [laughs]—among other things—teaching huge classes. That wasn’t all that much fun, but it really felt like you were at the developing stage in the institution, [which was a fun experience to have.] TW: Do you feel that Western’s been a university that has explored—or has supported—the expression of creativity, thus encouraging creative people to teach here? Like, did you have the freedom here to do..? CL: Yes, we had the freedom. Now, [inaudible] if I interpret creativity as being able to [explore writing in my field.] We didn’t have much time to do that. In European history, we didn’t have any resources. To show you how unsophisticated I was, when we moved up here, I thought, well, we’ll be close to the University of Tennessee library, so I’ll do my research over there. Well, they didn’t have that many more [inaudible] than Western did then; they may have more now. I had been spoiled because the University of North Carolina then, certainly, was by far the best institution in the South for history of any kind. [inaudible] Chapel Hill’s library [was the Clifford Lovin 3 best, I thought]—and I thought all state universities were like that. We’re very lucky to be in North Carolina, where we have good state universities, and you can just accept that. But that’s not true everywhere. Certainly wasn’t then, more true maybe now. TW: That’s what I was about to ask, because I think what you’re talking about now is something Western has tried hard…with the North Carolina system and the library [inaudible] with Appalachia and the University of Asheville, and so I think that is definitely something that has come into play. What gave you the motivation to teach? I mean, the desire to teach. CL: [laughs] Another professor, I guess. I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life. I guess I was a sophomore and [the guy] who was teaching [inaudible] he was not a historian. He had a Master’s in Education, but he was so excited about his teaching and was so energetic, and I thought, well, maybe that’s something I want to do. And in my junior and senior years I took oral history courses and I decided that’s really what I wanted to be, and I never have questioned that. And I’m very, very happy with that choice. TW: Kind of along those same lines, how would you associate the terms being “cultured” with being “educated?” CL: [laughs] I guess they’re very—the way we use them—they’re very similar. I think you have to be educated to be cultured. Without education, you don’t really know [from 7:54-7:58, audio cuts out]. [inaudible] TW: I can certainly see that. In your career at Western, what were some of your goals? CL: [laughs] [long pause] I don’t know what my long-term goals were. I’m not sure, in the early years, I had any long-term goals. I wanted to be a good teacher. [And that was something I worked at.] I tried every technique and every method I could. I did a lot of evaluations in my classes, long before it was required. I simply wanted to be—and it’s such a cliché—but I really wanted to be a good teacher. [That was what I wanted to do.] And I always enjoyed some research and what I did was to try and figure out some research that I could do here. And I was able, in time, to do that. I did some publication and writing along with my teaching, and my family. My family enjoyed living here. Well, I just thought I was on top of the world. This was a good place to live and my kids loved it, I enjoyed my teaching, and [was able] to do a little bit of research. And also, at the institution, I came right before a large group of faculty came and stayed, and so early on, I was always a “senior” faculty [even though I hadn’t been there long]. TW: Where did your research end up going? Because I know that you said that it was hard for you to find resources. CL: Well, I picked a couple of subjects that were related to European history, but I could get the material in the United States and could get [inaudible] and things like that. Instead of studying the governments, [inaudible] things like the peace conference…in 1919, from the American side, because I could get a hold of American sources. [That’s what I was trying to do], American Clifford Lovin 4 relations to other countries—more into foreign policy than I could get a hold of material like that. TW: Could you please explain what “tenure” is and what it meant to you? CL: Well, when I first came here—and I think this is generally true in the 50s and 60s—if you got a Ph.D., you were assured tenure. In fact, I did not go through a formal tenure process. In 19—I think it was 1969—our academic dean decided—I guess it was academic vice president [inaudible] in 1967 maybe [inaudible] less political—but, because, to get university things in order, what he did was tenure a whole group of people at one time, who understood that they had tenure, but there hadn’t been a formal process. So, you got a piece of paper that said in 1969 [that you were tenured]. And so you know, I’ve looked at tenure from a lot of different angles [obstructing noise] that it was much tougher for people to get tenure. But I did not—and I have to admit, I did not go through that and having my Ph.D. gave me an advantage. If you kept your nose clean and had a Ph.D., you could get tenure. Not just here. Anywhere. TW: Do you remember— CL: [inaudible] Ph.D.’s, I remember. Very few. TW: Do you remember a time when tenure first did pop in as a structured thing at Western? CL: Mhm. And that was—it was ’69—it was a time we were organizing into schools—the schools of arts and sciences. I became early on—I can’t remember the year—assistant dean. And as assistant dean, I played a part in the tenure process as it developed. It became a very rigorous exercise, and we were able to recruit faculty. That’s something that changed very quickly. In the 60s, it was hard to recruit good faculty. In the 70s, all of the sudden, there were a lot of good Ph.D.’s that we could recruit and pick and choose and then we could go through the tenure process [inaudible] and then we could get somebody else. [And so that’s what we could do.] TW: Right. When I was researching for this project, I came across a professorship quote that spoke about the characteristics of courage, integrity, and perseverance all being defining qualities of a professor. In what ways is that statement true? CL: Certainly integrity. It’s one of the things that’s so important, you know, it’s always looked at; [your character]. That’s true in everything a professor does. You can’t trust if everybody—students. [Well, and] the fact that if the administration didn’t trust the faculty, there’s not going to be one. I watch [her courage] [inaudible]. What was the third one? TW: Perseverance. CL: Yeah. [laughs] You got to follow through with everything you start. And all the things…you know, some people start off strong at the beginning of the semester and some taper off. [Some students, the faculty and many, see, are not surviving.] [inaudible] Now, when I said we didn’t have tenure before, I don’t mean people who came, stayed. You just told them to go and you Clifford Lovin 5 didn’t have to worry about suits or anything like that you’d just say, well, [we just got someone and want to change positions] and that was the end of it. TW: Kind of sticking with these characteristics, in what ways was integrity exemplified throughout your career? Or maybe there was an example that really stands out, when integrity was really needed. CL: [long pause] I really can’t do that, I don’t think, because I just think it’s a constant. Going back to courage, there were times when we had to have courage. The courage of your convictions, to stand up and say, okay, I believe in this, and if that’s something that you can’t accept, then fire me. And that takes some courage. But integrity, in my mind, you can only illustrate it by its lapses, [and I don’t want to do that]. [laughs] TW: Right, right. CL: But when the lapses occurred in the faculty, they were usually gone the next year. TW: I think there’s, in some ways, a complacency among college students now. And of course, when you’re researching something like this, you look back and you read about students protesting Vietnam and stuff like that. My question was, was courage ever exemplified in your teaching career? And if so—or if not, were there any instances where you saw courage exemplified on a college campus? Or, this college campus, I should say. CL: [It’s not]—you mentioned Vietnam, and there was a lot of debate on campus by students and faculty. [inaudible] It was a much more exciting time, I guess, on college campuses back then. Students were much more involved in general political issues, but also campus political issues. [I remember students and faculty] would take stands. I know [laughs] I was involved in the [inaudible] Vietnam, and I know it took courage, but I took the position that we ought to withdraw from Vietnam, because we didn’t know what we were doing. They had a plan, but nobody knew what it was. I was able to do that because I’d been in the Army. I wasn’t protesting military service, and that gave me an advantage. And I always thought it was kind of curious that the people who argued most vigorously for more involvement were the ones who never served. That’s not—[laughter] I’m not sure I can—the greatest examples I saw were those during the Carlton years where people, even people without tenure, were willing to protest and sign documents that might have meant their dismissal. That was a special kind of case. I saw it in a number of people I wouldn’t have expected. And I saw, not necessarily the lack of courage, but an unwillingness to stand [in front of all these people], too. But I think that was a unique case. TW: Are there any other characteristics you would add? CL: Well, [laughs] we all know a professor has to be intelligent, [someone to train], but it takes a lot more than intelligence to be a good professor. You have to have a sensitivity to the needs of your colleagues and your students. You have to be able to communicate effectively. It doesn’t make a difference saying what you know if you can’t get it across and if you can’t get your Clifford Lovin 6 students interested in it; it’s not enough. So, in looking and choosing your faculty people, you had to look at—not just what they’d been doing in their grades, academically and things like that, but you looked at whether or not they’d be able to effectively communicate to our students. And our students were special. We wouldn’t bring in someone who would denigrate our students. Our students were poor; most of them were first generation. I know that’s not true anymore, but it was true then. And people coming in, thinking they were coming in counted as missionaries to us dumb people in the mountains. It just wouldn’t work. We had to screen them. We had to make sure we looked at whether or not the individuals who wanted to teach there could communicate effectively with their students. Communication and sensitivity are two of the most important characteristics we looked for. [inaudible] TW: Was that an involving process for you, as a teacher? Or was there a good example of that here when you showed up? CL: Well, there were good examples. [Craig Sossman] was my mentor, I suppose. He was with [inaudible] and he was…actually he’d had the same advisor I’d had at Chapel Hill, so we had a lot in common. And he was determined that we would be excellent faculty and that our students, once educated, were as good as any students, anywhere. He’d had more experience in teaching than some of us. So he’s very important as a guide, and when he stepped in as department head, [you could tell state] [inaudible] Well, Max Williams and I [inaudible] He had this sense of integrity that was absolute. [laughs] He would fight for his principles, at any time, anywhere. And sometimes it would prove minor points. [laughs] TW: There are obviously different parts to being a professor, there’s obviously the classroom part, and we talked a little bit about the research part…was there ever a time in your classroom where things were not under your control and you just wanted to give it up for about a week and just walk away and not…? CL: [laughs] I’m not sure I remember. One class I had [laughs], the kids were just doing awful. They were flunking the tests; they were not paying attention. I don’t know what it was. After the class was over—it was the worst class I think I ever had, it was a large freshman class—I went to the registrar’s office, after it was over. I mean, I thought I’d lost it. And I got the registrar to give me a print-out of the class rankings and SATs of the students from the class, and it happened that I got the dregs of the freshman class. I didn’t—I mean somehow, the machines gave me all of the dumbest students we had admitted. I mean, you know, in a class of a thousand, you’re going to have thirty or forty that are not too swift, but I had them all. [laughter] So it turned out it wasn’t my fault. [laughs] I probably did as well as I could do. No, I don’t think I ever would quit teaching. And I don’t think I…that’s the one thing about college. You’re always—I think the best thing about my experience was we just had great colleagues in the history department my whole career here. You could go talk to anybody about any problem and they had it, too, and you could discuss matters, you could discuss content, you could discuss relationships with students. You always had people that were willing to talk to you about what you were doing. I think that’s really important; you were never by yourself. That Clifford Lovin 7 was one thing [that was trouble] at Central. [laughs] There was one other history teacher and we didn’t get along. [inaudible] There was nobody to talk to. And here, that’s always been [inaudible]. TW: How far were you in when you had that class? CL: Not too far [laughs], maybe three or four years. It was early on, and it helped me, because after that I realized you could get a class that was not—especially freshmen and sophomores—that was just assigned to you, instead of upper division courses. Upper division courses were different. People chose to take those. TW: And thankfully, you never had a class like that again? CL: [laughs] Not that bad. I certainly had some. I remember right toward the end of my career I had a class that was close to bad. Fortunately, I had another class that I was teaching the same subject matter, two hours before, and they were doing great. I was teaching the same thing, using the same techniques, so I knew it wasn’t my teaching. There were other things at work there. I think that first experience helped me all the way through. I could always make the excuse that I [laughs] had a lot of bad students. “Bad” is an [awful] word—students that weren’t very good in history, I should say. TW: Do you remember—and you probably—this is a tough question. Do you remember any of those students, later coming into the history department, and turning for the better? CL: Well, but I do remember a lot of students, [but I didn’t have to teach them in class]. There’s a tendency of the faculty, this is what people say, they want to teach the upper division classes. That’s what they really want. Freshman classes, we just have to teach to make money for the institution so we can teach what we really want to. I liked upper division classes, but I liked freshman classes at least just as well, for the very reason you suggested. What you could do in those classes—you could have individuals, students, who were very bored, that hated history, and you just make them do the work, and they would do the work. At some point maybe in the semester, the light would come on. And you could see that. You could really turn students, and not necessarily just in history. This student in one class that I talked about, we talked about economic developments and ideas of communists, so especially after the industrial revolution [inaudible]. I remember one student coming back to me in her junior year, and she was a major not in history, but in economics, and she said it was because of what I talked about in that class that she wanted to do that. I was never trying to make people major in history. I wanted to make sure they understood some history, but the one thing about the university is there’s so many different majors and good things, and that’s what I want. I think sometimes, we get too tied up in our own departments and our own majors, and we want to count our majors as a record of our success. I never thought that was necessary—a measure of our success. And teaching freshmen, for example, is to make sure they have a good general education for whatever they go into. That’s the reason we have to keep focus on the individual classes, not on the neighbors here and there. Clifford Lovin 8 (Audio clip B is transcribed further) TW: Dr. Lovin, could you tell me about Carlton? CL: [laughs] Well, we have to at least say that the university system, created in 1973, nobody knew what that meant. But we were looking for a new chancellor. Our chancellor, we’d had a very vigorous chancellor, who had health problems. [That’s P.O.W., p-o-w.] In 1972 to 1973, we were looking for a new chancellor. But the board of trustees decided this was their choice and their power was going to be taken away. They didn’t want any faculty on it. For example, the football coach to the search committee, not a faculty member. But, they were having trouble. They tried to hire Robinson, who later came as chancellor, but he had just moved to Purdue, and he wanted to come, but he didn’t want to leave after his first year there. They wound up with a junior college president named Carlton, and he was appointed just a few days before the board of trustees lost its power under [the new law]. I’m sure what they were thinking was let’s have somebody who’s beholden to us and we’ll continue to have some control under this new system. Well, that’s the background. Carlton was a very nice man; he was a chemist. One of our chemistry professors had him in graduate school. He apparently was a good chemist. So we didn’t have any doubts—he was fine. He had called me; I was out of the state—I was teaching in Colorado in the summer. And he had called me from here after he took over. He wanted me to be chairman of the study that the [inaudible] association requires us to do every ten years for accreditation. This was a big job and I was impressed by myself, of course, and I agreed to do that. So everything started off fine. He was well-spoken; he was a tall, handsome—he looked like a [inaudible]. And in the first semester, everything seemed to go along pretty well. He needed a new academic vice president, and he was looking for one. He would invite people, and he did, in fact, [like meeting these people] and so on, and it was a lot of formal processing, but— TW: Where were you at the time? Meaning— CL: I was Assistant Dean of Arts and Sciences, you know, I taught part-time, and I was in the dean’s office part-time. That was a new job. My main job was to deal with students within the school and I didn’t give up that job to take this other, I don’t know why, but it meant I didn’t teach at all that particular year. So, I was completely free, [I had my study], I had my own secretary, so I was hot stuff. And we organized it, we put together a good plan, we worked hard, and everybody on the faculty was involved in the study, and everything was going well. In January 1974, I guess, sort of suddenly, the Chancellor announced he was going to end tenure—he was going to suspend tenure for a year. He said I’ve got to wait until I know all members of the faculty. And he made some unfortunate statements. He said I need to rank order faculty. That really got into our minds, you know, we’d start talking [rank on the sides], you know, “I’m number 115.” But I don’t think that’s what he meant. He meant—he could’ve done this without saying anything, but the thing is, he announced it. Of course, tenure is one of those things that faculty members think is the greatest thing in the world; it’s our job security. And it is important. For an administrator to unilaterally say I’m going to suspend it for a whole Clifford Lovin 9 year, it’s just not acceptable to any kind of organization, like the AA and the UP and even [inaudible] association. Everybody was upset by that. It really upset everybody, and when people tried to protest—two deans decided to protest—they decided to protest by handing in their resignations, and he accepted them to everyone’s surprise and amazement, including my boss. Which meant, without any attention, I became acting Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences. I was very young and inexperienced. But he never named me dean. I was still assistant dean, therefore I had to act as dean. And so, I was doing a double-job as Dean in the spring semester. Max went off to England; we had a program that went to England, and so my chief pillar that I leaned on for anything was gone. We, in the arts and sciences, decided to protest what we considered, really, the firing of our dean. He was a very popular man; a very good man. We signed a petition to call on the university system to investigate the chancellor, that’s really all it was. We, within two days, got signatures of 75% of the tenured faculty, and a few members of the other schools, not many. And most of the untenured faculty, but we refused to let them sign because their job was on the line; they could be fired. They signed it anyway and [Craig Sossman] kept the copy of their signatures in some secret place—I can’t remember whether it ever came out or not, I guess it did [TW laughs]. We didn’t want them to be at risk. This began a real battle. The petitioners met periodically, the people who’d signed, they elected a [steering] committee. I was a member of that—I was a member, [inaudible] and [Marilyn Jody]. [Those were the members]. We were the committee, and we sort of directed things. It was interesting—ironic, really—that I had a secretary first, before Carlton, that I could use to do anything that I needed [TW laughs] to do. And we agreed to try and keep this in-house. You know, we didn’t want to create a big—we wanted to fight this out from the inside. We didn’t have any idea to get rid of him, we just wanted to straighten him out. [We didn’t want to fire him, we just wanted to do that]. And as we talked, we agreed not to publicize it. Well, as soon as we agreed to that, he put an article in the Asheville Citizen and just painted us rebels; people who were uninterested in the institution—just awful. And you know, it really made us mad [TW laughs]. So we met, and the steering committee got the permission of the petitioners to put out our side of the story. And what Carlton didn’t know—and this is part—you see, he was awfully dumb in a lot of ways. Naïve is the best I could put. He wasn’t from North Carolina—he didn’t know anything! He didn’t know anybody in North Carolina. We knew the people [we worked with.] I had been a classmate to the guy who was [integer] to the Charlotte Observer. So when I wanted to get the message out, I didn’t call the Asheville Citizen, I called the Charlotte Observer. [inaudible] I told him what was happening, and he said I’ll have a reporter call you back in ten minutes. We were on the front page of the Charlotte Observer the next day. You know, so if he wanted to get into a pissing match, [TW laughs] we were ready. And he just—he didn’t know what to do. He never understood what he had done. What he had done was to say, in effect, that you guys don’t know what you’re doing here. I’m going to help you. I’m going to lead you out of Egypt [TW laughs]. And you know, here’s a guy that was president of a junior college—and we’d found out later, he’d been run off from there. He’d been run off from three administrative jobs before we’d picked him up. That shows how bad a job the search committee did. But, he just made mistake after mistake. Finally, made him write an apology Clifford Lovin 10 letter, which he had to read to the faculty [sit-in]. And he agreed to take back his suspension. We kept meeting, because nobody knew quite what was going on. Well, to put a long story short, when tenure time came up, all the schools made our recommendations. He turned down all the recommendations from the School of Arts and Sciences. All the recommendations, promotions—oh, well, one—he gave us one tenure, maybe two promotions. And you know, we had a young faculty, and we wanted to keep them. So, we had a fairly large—and I don’t remember how many—amount of recommendations. And we expected that he’d turn down some, but not turn down virtually all. So, what we said, in effect, was, you did keep the suspension. You said you were going to lift it, but you really didn’t. And what turned the tide really against him—he thought he was going to get away with that—but what turned the tide against him was that the Dean of Education sent him four of them, and he turned down two of them. So, he got half of them, but he was more ticked off than we were, because he had supported the Chancellor all the time that the Arts and Sciences were fighting him. You know, he's our Chancellor and we’ve got to support him. But when he did that, he immediately called his faculty into session, and they passed a resolution against the Chancellor and asked for this investigation that we asked for earlier. So, they joined; that whole school joined the movement. Anyway, they did put together a [steady commission] that came up in the summer, and they decided although the report said it was faculty’s fault, the Chancellor didn’t react [inaudible] and moved him, moved him down to Chapel Hill [inaudible]. So, we got what we wanted. And really, that was the end of it. Petitioners, you know, it was a tough year; a hostile year. I had to meet every Friday with Carlton because [he was on the committee] for this other association. [laughs] And we would even talk about how strange it was that we would make these statements about each other outside, and yet we could sit down and talk. And I kept saying, why can’t we solve this thing? His basic answer is, I understand what it was. The only way we could solve this is to do things my way. This is not a democracy. This is my job, and you have to do it my way. I have to have this kind of control, or I can’t do it. And that’s not acceptable. It just happened that I was in a position, because of that position as Assistant Dean, and of course, it ruined my chances for administrative advancement, for the time being. I had to, as the perceived leader of this “revolution,” I had to be real quiet in the future. In time, we got a new Chancellor. Robinson came this time. He was very suspicious of me when he first came in. I was Chairman of the faculty at the time, and he had to deal with me directly, but he didn’t really like it. But we were able—in fact, [Dr. Wood] and I, along with the [inaudible] members of the organization—we were able to put on a faculty retreat for him to meet the members of the new faculty the first summer he was here, out at Fontana. I think he realized we were not the bad guys; we were not trying to hurt the university. We didn’t really [care whether we got rid of Carlton or not], we just wanted him to be somebody who recognized the value of faculty and used us in the ongoing development of the university, and he just hadn’t done that. Robinson realized that. [inaudible] He gave me a couple of very important jobs while he was Chancellor, [and I appreciated that] [inaudible]. And later, eventually I became Dean [inaudible], I’d been in the background a long time. The animosity, it’s the people who didn’t sign the petition in the Arts and Sciences, we really thought them the bad guys. [There were bad feelings there]. Most Clifford Lovin 11 of us, in a couple years, got over that. A few people held on to it far too long. And people had got caught in it, like the Dean, who lost, really, his career. That really made some people bitter, and I understand that. But we were able to rebuild, and it did not do much permanent damage on campus and Robinson, who was a brass kind of person, always recognized ability and talent, wherever it came from. So, people who had the ability [inaudible] to work well with him when he was Chancellor [inaudible]. And we were better for it. We didn’t really lose any—we lost a few junior faculty [inaudible], so we lost some [inaudible]. [We lost a history professor who] took another job because he could. That was unfortunate that happened. [inaudible] [But maybe it was good for the university]; a part of growing up—part of the whole reorganization movement from a small college to a university [inaudible]. TW: How much was the student body—how much did the student body know, what was going on? CL: They got involved too [TW laughs]—in fact, a guy in history who fought in Vietnam was President of the Student Body. TW: What was his name? CL: [Wyatt] [inaudible] TW: Yeah, I’ve seen pictures of him. CL: Yeah, got some pictures out there, probably from [‘89]. [inaudible] They had some issues—they were basically—they had the same, basically the same, principles, but they were different issues. It was a time when students acquired more power, shared power on campus and stuff. And he wasn’t going to [let them have power and then him have less power]. And so, [we worked hand in hand]. And the people on the other side thought that this was some great conspiracy, that I was sitting in some office, pulling all these strings. Of course, that wasn’t the way it was at all. There was a strong feeling about what the Chancellor had done and about what he was refusing to do to compromise. And they marched on his house [a time or two], [the students did that] [laughs]. They were very active, and the newspaper wanted to put out an April Fools’ issue [inaudible]. But they were very much involved; they were very active. Back then, too—we talked about this earlier—back then, too, the student newspaper was a lot more active. I don’t know why, but it was a lot more fun. The whole campus was like an organism. And we did the learning—the teaching and learning, but the students were involved in a lot more than that. [Like in the newspaper], they wrote real editorials, they wrote real news. This whole battle was in the student newspaper every week. TW: Since we talked about Carlton, what event stands out in your mind as having the most incredible impact on the university? CL: Since [inaudible], is that what [you’re thinking]? TW: Yeah, probably. Clifford Lovin 12 CL: [long pause] I’m not sure that—I think the whole administration of Robinson was a…he was not a patient man in what he was doing [inaudible] while he was Chancellor. I mean, he was just—he made tenure much more rigid and hard to get, [he made sure it was harder to get]. He did more for the library; he did more for legislature, with money for buildings for books, for a whole variety of things. He brought faculty members who he thought would be…he was very interested in the search for faculty, [he would rank their names nationally]. He had a vision that was not the vision of everybody, and we never achieved his vision, but what he did was he brought us into a new—so I think that whole period, we all breathed a sigh of relief when it was time for him to retire. But the fact is, the next ten years we had Coulter and we had a much more peaceful time, but we were ready to build on a foundation [inaudible]. So, we were a very different institution [since 1966]. TW: Who was the most influential visitor to Western? CL: [long pause] Well, we had [inaudible]. Nobody comes to my mind that would be a visitor that made an impact…significantly. [inaudible] The Chancellors [in our system] had a great deal of power—that’s what Carlton realized: he had power. But you’ve got to use it with sensitivity and an understanding of how it works. That’s what surprises people [inaudible] that we got rid of him, nobody’s ever—very few times has the faculty ever gotten rid of the Chancellor. But he was just—he kept making key mistakes. They would’ve never gotten rid of him if he were smart [inaudible] tenure decisions. [There would’ve been no way] he could’ve maintained this adversarial system. TW: But do you think it came to a point where both parties were ready to let go? Do you think he felt like, maybe it is better if I just get the heck out of here? CL: Well, he never made that decision; he was fired. [TW laughs] He was fired, there was no—he didn’t have a choice. The committee that came up here and studied recommended that he be…[They] did not recommend any sanctions [inaudible]. [He blamed us for starting it]. But there was nothing we had done that was so unacceptable that they didn’t try to get rid of any of us. Nobody was specified. And nobody was punished. We felt like—there were some we felt like were leaders who got…smaller pay raises and shifted out of [inaudible] and things like that. [But it wasn’t a bloodbath] [inaudible]. There was no general punishment. [We’ve never got one of these oral tapes] like this before. We’ve come real close a few times. But everybody would like to know what he thought. Nobody knows now. [inaudible] what was really behind us. [He] wanted an outside Academic Vice Chancellor, too, [and he was not very good at that give and take, like a lot of people]. What he should’ve done is he’d take—if he’d taken his Dean and the other, who was his Academic Vice Chancellor [inaudible] coming from the outside himself, he’d get somebody on the inside—I don’t think this would’ve ever happened. (Audio clip cuts out 26:26-29:56) TW: What’s one of your worst memories of teaching at Western? Clifford Lovin 13 CL: [inaudible] I don’t remember…any…The thing about teaching is you can get clobbered one day and the next day, it’s wonderful. You don’t remember the clobberings. Sometimes you just get—you feel prepared and you think you’ve got it [inaudible] and you can’t pull out of it. People ask you questions that you should know and don’t know. [inaudible] I don’t know that I ever was faced with a…Well, I remember one student [that claimed that I gave her a bad grade] because she was a black woman. And I said that’s fine, [you challenge me] [inaudible]. And she didn’t get anywhere, because it was not true [inaudible]. I don’t remember another challenge. You know, I had individual people come in and tell me, you know, I don’t think you gave me a fair grade. I would have everyone’s [inaudible] criticisms, [inaudible] people who cheated in the class. And, I would, as a result, I would be careful about more things [after then]. [But those were some challenges] [inaudible]. [The main reason] [inaudible]. I don’t—what would you—what do you think… TW: No, I just didn’t—you had talked about earlier about the girl you had taught, who was going on to becoming an economy major because of the economics you had taught, and I didn’t know—I think the example you give of someone challenging your grade, maybe that had— CL: Oh, I know. I had a—but this turned out good. I had a couple of students, early in my career, whom [I got pushed to]—that didn’t happen very much. I was very much [the professor]—I’m the professor; you’re the student. [inaudible] but it never got different for me. But, for—I guess because I was young, and these were really bright—really bright kids—they all went to graduate or law school. And we had a sociology professor, who just had a Master’s, he was a really nice guy. These guys threatened him—there were about three of them—and I don’t remember the exact…you know, they went in and really, were big men on campus and acted like, if he didn’t give them better grades, they were going to—they were going to hurt his career. And he told me about it, and I [inaudible]. And I said, you guys have really embarrassed me, yourselves, and everybody who’s ever taught you. And, boy, did that shake them up. They came right around and did the right thing—one of them that I remember, I still keep in touch with him. He was—and I threatened him; I said if you don’t [send him an apology], I said you guys won’t graduate. I’ll fix it. [TW laughs] And they did all of the things they were supposed to do. And this one particular guy, who went on to Chapel Hill, to law school, [and he was in] the top ten percent of his classes—been a very successful lawyer ever since. They all were very successful. They just—they got…full of themselves. And I felt if that had been allowed to happen, that would have been one of my real bad experiences, because I had sort of taken these guys under my wing, because I knew they were going onto school, and I was trying to help them out. And they had used this—that they were going to get a bad grade—one of the group, one of the three, this guy had come up to me after the first test [inaudible]. Professor—he said—professor, I’ve never made an “F” before. I said, I hope you don’t ever make one again. And I said, do you want to—do you think you didn’t make an “F” on this test? Did you look at it and see what I wrote? And he just said, I’m not supposed to make an “F,” he said, I’m a—a—a…I don’t know what he said; I’m a big man on campus; I’m [big type]. And of course, I treat him like I’d treat anybody. I just said well, I hope you do better, and I’ll work with you, if you come Clifford Lovin 14 in and talk about things. And he thought he was an A student. I never did think that he was an A student; I thought he was a B student. He made his B and then he took courses with other people, which is what students have the right to do. That’s—that’s fine; it wouldn’t bother me a bit. But he was in this group, too, so...and I kept tabs on him [inaudible]. He’s just one of these guys…who campus is—you know, college, is just a place for him to play politics. He did—he got all of the [plum] jobs. He was head of the U.N. on campus. We had a U.N. conference here on campus and Dean [Rusk] was invited, the Secretary of State. He did do this kind of stuff very well. But I don’t—I really—it’s funny, I really did like to teach, and I enjoyed it. TW: Do you have a best memory? CL: No, no again. Those memories are like the daily memories, you know, you just, boy, you just [wore them out today], you just—it’s perfect. I did exactly what I wanted to do. And you can tell when students are listening; you can tell when they’re paying attention; you can tell when they sometimes, you know, [inaudible]. You just love it. TW: [laughs] Yeah? CL: A lot of times you just struggle. Everybody’s got [inaudible]. TW: Did you prefer teaching to research? CL: Yeah, yeah. I liked doing research, but I would never give up teaching [for research]. TW: The current administration wants to increase Western’s enrollment. Some feel it would be beneficial to the local economy; others feel it will hurt Western’s sense of small community. What do you think? CL: Well, I don’t mind some growth, I’m not—I guess I’m not interested in [just growing for the sake to be bigger], because we do have a unique situation here. Not only are we relatively small, but we’re one of the few institutions nowadays [inaudible] on campus. That’s one of those thing’s that’s changed since I went to school. Everybody knows everybody on campus, somewhere you’ve been staying for four years. People just don’t do that. People are going closer to home [inaudible]. So, we’ve got something very special and different, and I want us to keep that. Also, my biggest complaint [inaudible] that we have so emphasized this enrollment thing that we keep losing this word “retention.” “Retention” is the code word for “keeping people to stay.” [inaudible] I don’t know why—it’s unfortunate. We’ve gotten to that point…the Chancellor always says, no I’m not coming, faculty are supposed to be there; I want you to [be rigorous]; I want you to do [all the things]. But if he’d been a teacher as long as I had, he’d know there aren’t other things [inaudible]. People don’t flunk out because professors aren’t sensitive to their needs, you know, I’ll do a study session, when I—you know I used to do those things. You want to know who comes? The people who are making “As.” Every time. I’ve—I don’t have time to do that anymore; I’ve quit it. Those people don’t need it; I don’t need to come from my house up here to meet with four people who are going to make “As” whether I come or not. Clifford Lovin 15 The people who need it, don’t come. And I was always [inaudible] I would never give out outlines and stuff like that—questions for the exams. Not because I’m mean. TW: Right. CL: But just because I think that’s part of the testing process: you have to put the answers together in class, and while you’re writing the exam. You have to make the [inaudible]. I give you those ahead of time, you could write them out and print them out and memorize it, and I don’t think that’s what I want to find out about. And I don’t think it makes that much difference on the grades [inaudible]. My grade was an understanding that [inaudible]. [The other people] grade with the understanding that they did and they’re going to expect more. So, I don’t think my grades [inaudible], it was just a different technique. TW: If you had the money to make any change you felt necessary at Western, what would it be? CL: [laughs] Well, I [talk about this, if I win the lottery], my wife and I always talk about what we’d do, you know, we’d set up some kind of fund here. The fund we’d set up is for faculty travel. So, because we’re in a pretty remote place, faculty often can’t go to the conferences and do research [inaudible]. I’ve always thought the science people had it better than we had, because they had a huge equipment budget, and, so, they could bring in the things they needed to do research. We need money to go to Washington and Europe. TW: Mhm. CL: [inaudible] And, you know, the money we get to travel is two hundred dollars a year. And that’s just—well, we—I just think that the—and two hundred a year won’t even get you to the [Southern Historical Association] meeting. And we just—I’ve always thought—and this is something we’ve just talked about [inaudible]. If we had the money, we’d set up a trust fund for faculty travel. And as long as there was money, it would be for any kind of travel that would benefit faculty in their role as a faculty member. TW: Well, because of lack of status, low pay, and lack of accomplishment seen in other professions, is teaching a [troubled] profession? CL: [laughs] I don’t think so. I think—and I don’t want to make judgements for other people—but I think people who complain that way are either just talking about, parroting, what other people say, or else they don’t really like to teach. And they have some kind of idea that because they were not happy in teaching, if they were doing something else, they would get paid more. Mostly. I think our pay—I think we have some people who choose teaching who could make more money in other places. Some people choose teaching that couldn’t make as much in other places. And I don’t think that pay is all that [inaudible]…I think that we get perks. Just having retired, made aware of the fact no one can steal our [RAs] if you choose the state system, you’re guaranteed, as long as the state operates, a good [state retirement]. Plus, health insurance—free, for the rest of my life. [For all of us; all of us get free health insurance.] Given Clifford Lovin 16 the way things are now, that’s about as big a perk as you can imagine. I don’t believe you could calculate the value of that, for a ten-year period—for the next ten years, I don’t have to worry, between—and of course, it fits with the Medicaid system, now—[those two systems are working for me]. TW: And your children, when you were— CL: When I was teaching, yeah. That’s remarkable. So, I—I don’t—no, it’s not a troubled profession. In fact, in my six years as Dean, we recruited nationally for every position, and we always got our first choice. I was very pleased at that. These people, they wanted to come here because of what—because of the teaching. [We couldn’t offer them insurance]. And so, I think this is a very strong institution, and my concern is we keep it that way, because for me, the fundamental—the foundation of many institutions is the faculty. TW: I have one last question. And I’m going to change it—originally, I had, if you had to do it over again, would you still become an educator, but I believe you would’ve anyway. If you could go back and change anything over the course of time, would there be anything you want to change? CL: Little things. TW: Nothing big? CL: [inaudible]. You know, if I’d wanted to be a college president, or something, I wouldn’t have been so up front [inaudible]. In fact, they told me if I’d just been a little less…outspoken, they would’ve made me dean, permanently, here. If I’d wanted to be [inaudible]. I—but, you know, given—I think [inaudible] the most important thing I ever did. You know, I’m proud of what I did. I’m proud, because I think we saved this university from ten years—at best—of a very mediocre leader. And I think that would hurt us very, very badly. Because we had [enrollment] problems during those years, anyways, because that’s when the high school graduation rate was [inaudible] and if we’d had a bad chancellor at the same time, I believe this institution might’ve just collapsed. So—and it was, it was satisfying. So, I don’t think I would. TW: Well, thank you, Dr. Lovin.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Tony Wagoner interviews Dr. Clifford Ramsey Lovin (1937-2015) on November 13, 2002. Dr. Lovin began teaching at Western Carolina University in 1966 and continued to work for many years as a history professor, and later, Assistant Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences. He talks about his experiences as a professor and with the institution as it underwent many changes; for example, when Jack Carlton was hired as Chancellor in 1973. He also talks about the years under Chancellors Robinson and Coulter, as well. Dr. Lovin talks about the immense changes that WCU has undergone over the years, including changes to campus, the faculty, and the students.

-