Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2683)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (15)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- 1700s (1)

- 1860s (1)

- 1890s (1)

- 1900s (2)

- 1920s (2)

- 1930s (5)

- 1940s (12)

- 1950s (19)

- 1960s (35)

- 1970s (31)

- 1980s (16)

- 1990s (10)

- 2000s (20)

- 2010s (24)

- 2020s (4)

- 1600s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 1910s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (15)

- Asheville (N.C.) (11)

- Avery County (N.C.) (1)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (55)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (17)

- Clay County (N.C.) (2)

- Graham County (N.C.) (15)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (40)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (5)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (131)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (1)

- Macon County (N.C.) (17)

- Madison County (N.C.) (4)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (1)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (5)

- Polk County (N.C.) (3)

- Qualla Boundary (6)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (1)

- Swain County (N.C.) (30)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (1)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (3)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Interviews (314)

- Manuscripts (documents) (3)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (4)

- Sound Recordings (308)

- Transcripts (216)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newsletters (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Publications (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- African Americans (97)

- Artisans (5)

- Cherokee pottery (1)

- Cherokee women (1)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (4)

- Education (3)

- Floods (13)

- Folk music (3)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Hunting (1)

- Mines and mineral resources (2)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (2)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (2)

- Storytelling (3)

- World War, 1939-1945 (3)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Sound (308)

- StillImage (4)

- Text (219)

- MovingImage (0)

Interview with Luke Hyde, transcript

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

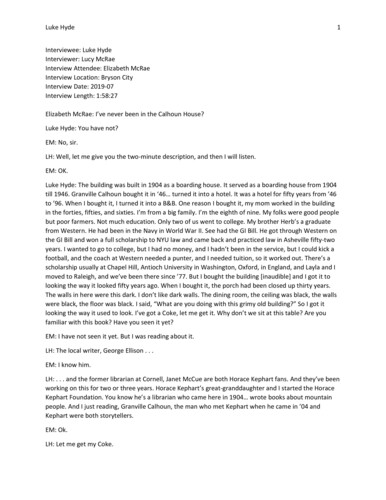

Luke Hyde 1 Interviewee: Luke Hyde Interviewer: Lucy McRae Interview Attendee: Elizabeth McRae Interview Location: Bryson City Interview Date: 2019-07 Interview Length: 1:58:27 Elizabeth McRae: I’ve never been in the Calhoun House? Luke Hyde: You have not? EM: No, sir. LH: Well, let me give you the two-minute description, and then I will listen. EM: OK. Luke Hyde: The building was built in 1904 as a boarding house. It served as a boarding house from 1904 till 1946. Granville Calhoun bought it in ‘46… turned it into a hotel. It was a hotel for fifty years from ’46 to ’96. When I bought it, I turned it into a B&B. One reason I bought it, my mom worked in the building in the forties, fifties, and sixties. I’m from a big family. I’m the eighth of nine. My folks were good people but poor farmers. Not much education. Only two of us went to college. My brother Herb’s a graduate from Western. He had been in the Navy in World War II. See had the GI Bill. He got through Western on the GI Bill and won a full scholarship to NYU law and came back and practiced law in Asheville fifty-two years. I wanted to go to college, but I had no money, and I hadn’t been in the service, but I could kick a football, and the coach at Western needed a punter, and I needed tuition, so it worked out. There’s a scholarship usually at Chapel Hill, Antioch University in Washington, Oxford, in England, and Layla and I moved to Raleigh, and we’ve been there since ’77. But I bought the building [inaudible] and I got it to looking the way it looked fifty years ago. When I bought it, the porch had been closed up thirty years. The walls in here were this dark. I don’t like dark walls. The dining room, the ceiling was black, the walls were black, the floor was black. I said, “What are you doing with this grimy old building?” So I got it looking the way it used to look. I’ve got a Coke, let me get it. Why don’t we sit at this table? Are you familiar with this book? Have you seen it yet? EM: I have not seen it yet. But I was reading about it. LH: The local writer, George Ellison . . . EM: I know him. LH: . . . and the former librarian at Cornell, Janet McCue are both Horace Kephart fans. And they’ve been working on this for two or three years. Horace Kephart’s great-granddaughter and I started the Horace Kephart Foundation. You know he’s a librarian who came here in 1904… wrote books about mountain people. And I just reading, Granville Calhoun, the man who met Kephart when he came in ’04 and Kephart were both storytellers. EM: Ok. LH: Let me get my Coke. Luke Hyde 2 EM: Ok. LH: If you will tell me, are we going to have one session. More than one, or does it depend, or do you know? Lucy McRae: Well, if we can get everything in, it will just be one. It might be a long one. LH: Well, as a lawyer, I like to sort of know and plan, and so on. How long are you comfortable, and do you want us to go today? EM: So, we generally… so our longest ones go between an hour and a half… I mean, if you’re comfortable about an hour and a half. Now, I think Lucy was working on the questions. We’ve also done follow-ups. So, we may get out, and there are lots of things she wanted to like when she started researching you. So we’re happy to also come back. Right? We can do part one and part two. LH: Let me get something else for you. Lucy, I don’t know if it will help, but this might make it a little easier to write against. Why don’t we do this? Why don’t we go an hour and a half, and then you decide if we need to go more or if you need to go back and work on it and let me know? I’m willing to do whatever you need and want. I do want to raise a question. When you first contacted me, I think another Swain County resident was a possible person to be working with you at the time. I think wasn’t it or was it? EM: She’d gone to school in Swain County. Ivy McPherson, who’d gone to Mountain Discovery, but we’re welcome, like if you want this interview to be housed in Swain County and Western, we’re happy to do that. LH: Well, I’ll work within your rules and regulations and guidelines. I do want to ask you this question. I’m not sure yet if I want to be identified by my real name or just a mountaineer. EM: Ok. LH: So tell me what it means to you. Which is more effective for you, and do you have a preference. Am I asking a silly question? Lawyers ask strange questions, don’t they? LM: I don’t know the answer to your question. EM: Well, I think it would be more helpful given, and maybe we’ll see how the interview goes for you to be identified by name just because I think in the content of the interview, it's probably not going to be hard to tell who you are. LH: Well, let’s leave that. EM: The other thing is that you can review once… we’ll record this. We’ll have a grad student transcribe it in the fall because if I made high school students transcribe it, they would never do it again because it takes so long. So they’ll do it. We’ll send the interview to you, right? You can read it and strike-through or decide even if we’ve done a follow up that you want to clarify or do some other things. And then once, you see the interview, and you make your edits then… and she has form here. We’ll ask for permission for us to post it on our collection, which is Mountain People, Mountain Lives. LH: That makes sense. Luke Hyde 3 EM: So you’re already a mountaineer by being in the Mountain People, Mountain Lives. LH: Well, I grew up here on the farm. I learned to plow mules as a boy and milk cows. Don’t want to go back to it, but I could. (Laughter) Ok, Miss Lucy. EM: Ok. I’m going to not talk. We can do that at the end. LM: Ok. Would you like me to tell you like kind of the order we’re going in? LH: I’m getting a little hard of hearing. LM: So first, I’m going to ask you about your family and just basic questions for the interview since we’re going to listen to it. And then I’m going ask you about Fontana Lake and like the compensation and then the Road to Nowhere and then your mom’s work here at the Calhoun House and your work as an attorney and then kind of your work in the Democratic Party and the Cherokee Preservation Society. LH: Foundation. Not a society. Foundation LM: We just have to say this for the interview. Will you give me, Lucy McRae, permission to record you. LH: Yes. LM: Ok. So for the basic questions, can you please state your name? LH: Luke D. Hyde. LM: Where were you born, and when? LH: Born in Swain County on Lands Creek about four miles from here. I’m eighth of nine children. I was born December 24, 1939. I said I’m one of nine children. All of my brothers and sisters and I were assisted the same midwife. There was no hospital in Swain County at the time. Very few doctors, so all of us were born at home with the help of a midwife. EM: Do you know the name? LH: Mrs. Burns. Mrs. John Burns. I don’t remember her first name. We always said Mrs. Burns, of course. But she was a skilled midwife, and she assisted a lot of people, but we had no hospital at the time. My folks never had a car... had to walk wherever we went. But I’m one of nine children. Four brothers and four sisters. Seven of us lived till adulthood, but I think that answered your question. I’ll wait for the next one. EM: What were your parent’s names? LH: My father was Ervin Marcus Hyde. E-R-V-I-N. My mother was Alice Medlin Hyde. Actually, her name was Florence Alice Eliza Isabella Medlin Hyde, and I wondered as a child… we all ended up with multiple names, and it used to embarrass me at school. The teacher would call several names, and I didn’t understand that until… when I was in law school, I got in a little scholarship to study at Oxford. The dean… I was working with the dean of law school in DC. And he wanted to start a program patterned on the English Inns of Court, so he arranged a scholarship for me at Oxford. I figured the if the English wanted to pay it, I was willing to go. And I’m of Scottish ancestry, so we went to Scotland, and I found out the Scots, a lot of Scots, had multiple names. So it was a custom in my family to end up with multiple Luke Hyde 4 names. So my father was Ervin Marcus Hyde. Didn’t have much education. My mother, Alice Medlin, a whole bunch of names Hyde had gone to the eighth grade, but mom had studied Latin. She was a reader and she… I get my love of reading from my mom. EM: So, you said you were one of nine. Can you tell me about your siblings? LH: My oldest brother Walter and all my brothers joined the Navy during World War II and after. My brother Walt studied electrical things while in the Navy and became the first noncollege graduate engineer that Duke Power had. Got out of the Navy, came back… he and my second brother, Herb, the one that became the lawyer, decided to be farmers because that was big then. They started farming. Our farm the mountains was this steep, and it was really difficult, so after one effort, Herb said, “this is crazy. I’m not going to do this.” He decided to go to college. Walt took a job with… then the local power company was Nantahala Power and Light. It later merged with Duke. So Walt started there, and then he went on to Gaston County, North Carolina, Gastonia, Belmont, Stanley down in that area, and spent forty years with Duke Power. My next brother, Harold, was a career military person and first in the Navy, and then he found out for his skills and the job he did the Air Force paid more, so he switched over to the Air Force. My next brother Barney worked in construction. Barney smoked himself to death in ’67, so I don’t think very highly of smoking. I had four sisters. Two of the sisters died in infancy before I was born, so seven of us lived to adulthood. My older sister Irene married a military person with a career, and they lived all over. She’s now deceased. My younger sister Sue is still living, and she lives in McDowell County, Marion, North Carolina, and she is our head cook here. She comes and helps run the Calhoun. So Herb and I are the only two to go to college. My sis, who is one of the best cooks on earth, and my sisters learned from my mom. Mom was magical with food. Mom was a short person. About 5’2 maybe 105 pounds, but she was a strong personality. I was very shy as a lad because my folks didn’t speak correct English. We used words that today would not be acceptable, and I was always a little embarrassed, and I’ll tell you more about that later. But that’s about my family. LM: So you said that your mother worked at the Calhoun House. Did she have any other jobs? LH: Let me think about that. Yes. Before she came here and maybe afterwards, the local mayor was Mr. Ted Hyams, and his daughter Sarah later became a clerk of court. Mom, at one time, looked after the clerk of court’s children. She had a good touch. I think that would be it.. the Calhoun and taking care of people’s children. LM: So did she work here while you were growing up? LH: Yes. My father died when I was eleven. At the time, seven of us. Poor people didn’t buy insurance back then. There was no insurance, so mom called us together and said we’re all going to get jobs. Your dad’s gone; we’ve got to get jobs. So I had to get a job at eleven. The rest of us got jobs. Mom came here. The daughter of Granville Calhoun, Polly, and mom were friends. So, Polly, I guess, had seen the paper and knew that my father died. So she called mom and said, “Alice, come see me.” Mom came over, and she and an African American lady ran the kitchen in the 40s, 50s, 60s. We would walk from the house. It's only four miles. I bought my first car at fifteen and a half because I got tired of walking. Drove a school bus when I was in high school. But anyway, to answer your question, as far as I know, the main job I know of was taking care of the people’s children working here as a cook. Mrs. Jackson, the black lady, was almost like a member of the family. I grew up Lucy before … I never heard a word of racial Luke Hyde 5 prejudice in my family. My parents had white friends, Cherokee Indian friends, and black friends. I didn’t know you were supposed to hate people because of the color of their skin. So I didn’t learn, but Mrs. Jackson was sort of like a member of the family. She and her family… we had a big farm, 100-acre farm. My folks were poor, but we had apple orchard, we had a blackberry, and mom and dad would let friends come and pick berries or get apples. Didn’t charge for them. People helped each other, so Mrs. Jackson and her family were one of those who would come and get apples from the orchard or pick berries. LM: What did your father do? LH: Dad was a manual laborer. He… my grandfather on both sides were woodsman. They worked in the woods as loggers. So dad became a logger and one of his brothers… all men worked in the woods. One of his brothers was killed when a tree fell and hit him. He was twenty-one or twenty-two, and that made such a huge impression on dad. He realized it was dangerous. He then took a job with what used to be called State Highway Public Works Commission. It’s now called Department of Transportation, but dad worked building roads. So he was a manual laborer. He would sometimes have to leave and stay gone two weeks because where the work was going. So I can remember him going and coming and going and coming. He died when I was eleven. Mom called us together said we’ve all got to get jobs. I got a job, and I had to fill out income tax in order to get a refund. That wasn’t much money. It was twelve dollars, I think, but if you’re eleven or twelve years old and don’t have any money, twelve dollars is twelve dollars. So I went to Mrs. White, who was the tax lady in town. I said, “Mrs. White, will you do my tax refund?” She did it. She charged me $2, and I thought that’s a lot of money. I knew not to trouble her until after April 15. I played ball with her boys, and when I was at Western, I ended up playing against Robert. He became All American at another college. We played against each other in college, but I waited till after April 15 and said, “Mrs. White, you did my tax return. Will you show me what you did?” She said, “Yes.” Sat down at her dining room table, she showed me. Next year I did my own. By the time I finished high school, I had done twelve or fifteen tax returns for relatives who couldn’t read and write. Now I didn’t look at the code to see if a person under eighteen could do tax returns, but they all worked, so I’ve been doing taxes since I was twelve years old. I later studied tax law in law school with Stewart Segal, who was chief counsel to the IRS. So I learned it practically, and then I learned it formally. I’ll be less wordy on your, on that. LM: What did you have chores growing up, and what did you do as your job? LH: I missed some… did I have what? LM: Did you have chores when you were growing? LH: Stories? LM: Chores? EM: Chores? Like around your house, did you have chores that you had to do other than your job? LH: Yes. I grew up in a house without electricity. I grew up in a house without running water. We didn’t get electricity or running water till I was a junior in high school. So I get back to the chores. I went out to play sports in high school because if I did that, I could get a shower at school, so I played four sports. But Luke Hyde 6 to answer your question, I was responsible for getting the wood in for the wood cookstove similar to the one in our dining room. So I grew up in a house with a wood cookstove and a fireplace in the living room. There was no central air, no central heat, and all that. And I would either have to get enough the evening before to take care of things in the morning or go in the morning. A lot of days in the morning, I didn’t have to milk cows, but a lot of time in the evening, I would have to milk cows. We had, you know, we had cows for our milk. We had chickens; we had hogs, we had goats. We had sheep, horses, mules. So I had to take care of the animals. A lot of times before I went to school, I would have to feed the animals. Especially after Dad died because of a lot of my brothers and sisters were gone. They were off in the military or wherever and so on. But yes, I had lots of things to do. I would have to keep two buckets of water in the kitchen. One mom would use for cooking and this that and the other and the other we had to use with dippers. We didn’t have plastic cups or paper cups then. You used the dippers. But I had to keep water in, had to keep wood for the cookstove. Wood for the fireplace. A lot of times, either before I went to school and when I came back, I’d either put the animals out to pasture or in the barn depending on… but yes, there were things to do. And the strange thing about it, Lucy, I never raised a question about it because it had to be done. You do what you have to do. I did think that there might be another way of making a living. (laughter) LM: Did lots of families when you were growing up have farms besides yours? LH: Practically everyone I knew lived on farms. And people . . . [Interruption by hotel guests] LH: Welcome back. Did you have a good walk? LM: Well, we just talked about… EM: The farm. LH: Most everybody I knew, and certainly my close friends, lived on farms. I got to know the people that lived in town who didn’t live on farms but fairly small number of people, but it was four miles out to where we were. I grew up on a farm surrounded on three sides by the park, which was Smoky Mountain National Park. Walking distance to Fontana Lake, and I just thought that was the way of life. It was the way of life. It’s less, so now. LM: Did you attend school in Swain County? LH: Yes. I first started… back then; they had… there was a little school at Lands Creek, and I started there. I was sickly as a child, and the doctors didn’t know why. First, there weren’t that many doctors. You had to go to Sylva or Franklin or something. I started school, and then the doctor said you need to hold little LD out. I went by the initials LD. Lucas [Dennis] so, I started at a little one-room school where one teacher taught all grades one through eight, and for whatever reason, I was sickly so somebody said hold him back. And then the school where the middle school is now up on schoolhouse hill was a cemetery. Started there and went to first. We didn’t have middle school then. Went through first to eighth grade and then went to high school there. I started at Western immediately after high school, Luke Hyde 7 and while I got scholarships. I thought I was going to be a great basketball player and football player at Western. I was playing one night, and I’d had a… I was fairly tall for a guard. I’m 6’1”. Back then, you didn’t have any 6’1” guards. Nowadays… but anyway. I would steal the ball a lot, and the other team didn’t like me stealing the ball and go down and making layups, so I stole the ball once, and two of the guys drove me all the way into the stands and broke my leg, broke my hip. So I was hobbling around Western on crutches and decided to leave, get the leg back in shape, get a little more money. So I left then came back, and that’s when the football coach offered me a scholarship. So I took five years to get through Western but to answer your question, yes, I went to school in Swain County then Western. LM: Where did you attend college and law school? LH: Finished at Western fifty-six years ago. Started immediately at UNC-Chapel Hill law. But I was student body president at Western my junior year and senior year. It was a small school then. We had about 2,500 students. I was active in political party then. We started the College Young Democrats. We had over 600 members in the College Young Democrats. Over one-fourth of the student body. It was a powerhouse. Jack Kennedy was running for president in 1960. We had meetings, raised money to send a group off to campaign for Jack Kennedy, and they came back with a plaque that said Outstanding College Democratic Club in the nation, and a lot of those people are still friends. If I pick up the phone and call one of those guys that helped me start that group, I don’t have to take two hours to ask them if I need something. In two minutes they say what you need? But anyway. EM: Who were the people that started it with you? LH: Charlie Smith, who later became Rufus Edmundson’s chief of staff. Rufus was Attorney General that ran for governor. Charlie went down in a plane crash while campaigning. Woody Dillingham from Buncombe County. Robert Davis from Jackson County. John Roper, whose brother James still lives in Jackson. Whole bunch of… young woman. Bonita Hopkins. We had about an equal number of men and women because I wanted it to be a powerful… we got enough people in. The political science professors were helpful to either political party. We had some good people at the time, but as student body president my junior and senior year, I had to give reports to the Board of Trustees. A local judge in Jackson County, Dan Moore’s wife, Mrs. Moore, was on the Board of Trustees, and apparently, Mrs. Moore went home one day and told the judge that boy’s been on every college campus in the state. I had visited every college campus as part of my duties in student government or playing football, and I had been appointed to some statewide committees to promote education and so when I was in law school at Chapel Hill, that first year there were no cellphones back then. The dorm phone rang one day, and it was Judge Moore. He said, “Son, can you come over to Raleigh. I need to talk with you about the campaign.” I said, “Judge, I can’t come today. I can come Saturday.” He said, “well, my headquarters are in the Sir Walter Hotel.” I said, “I’ll be there Saturday morning.” So I drove over, and he says, “I’m the oldest guy running for governor. If I don’t get young people, I’m not going to win.” You had to be twenty-one years of age to vote before the amendment before the [eighties]. And I said, “Judge, I’ll do what I can over on campus.” He said, “No, you’re not hearing me. I want you to work with we me in the campaign.” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “I’ve spoken to the dean. He’ll let you back in. I want you to leave law school and help me get some students on every campus.” I said, “Judge, I’m honored, but I don’t think that I can do this. He said, “Will you think on it?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “Will you ask your brother Herb about it?” My brother Herb, lawyer in Asheville, was running for the state senate, and the Judge knew that. I said, “Yes, I’ll ask Herb.” So I called Herb. Herb said it was a “dang fool idea; don’t Luke Hyde 8 do it. It’s too hard to get back into law school.” So I called the Judge back and told him. He said, “well, I’ll be in touch.” About two or three weeks before the end of the school year, the phone rang. I answered it. And Judge Moore said, “Son, I’m sending my campaign manager JK Sherman and Ed Woodhouse over. I want them to bring you over to Raleigh, and we’ve got to talk. I said, “Judge, I’ve got a car.” He said, “I know, but I want to send them over.” So they came over. They wanted to give me the sales talk. So on the way from Chapel Hill to Raleigh is about thirty minutes. They gave me the sales. They said, “look, we’re not going to win unless we get young people. Just come with us and help us this summer, and then you can go back to law school in the fall.” And they offered me a fairly good amount of money which I could use. So I started working, and within a few weeks, I had a group on every college campus in the state because I had worked with these people through student government. I played ball. So I called them and went to see them. And what they wanted was when Judge Moore had been places wanted young people to come out for the pictures. And as we got closer to the end of the summer… things were going well. And I had friends, three people were running in the Democratic primary. I had friends in other camps because I thought in some point we needed to get them to come to honor a candidate. So as we got toward the end of the summer, Judge said, “Son, I spoke with the dean; stay with me just to the election in November you can go back.” Well, foolish like, I stayed with him. He won. I stayed on with the next governor, Bob Scott. Ten years later went back to law school at Antioch University in Washington DC. My brother Herb had studied with Edmund Chan, C-H-A-N. The leading constitutional law authority in the nation. Seventeen, eighteen years later, I studied with Edmund Chan’s son, Edgar Chan, at Antioch University. I took constitutional law with the son, and when I met the dean, and he had learned that my brother Herb had studied under his father, we became close. He asked… students at Antioch had to handle real cases in DC courts. You had to go through extensive training for two or three months. And then we’d go to court in DC. Your professor would be somewhere in the building or in the courtroom with you, but we could handle cases in DC courts... special program. So I handled… if you can survive three years in DC courts, you can survive anywhere. But toward… Leila and I had gotten married at the end of my second year of law school. She was a TV reporter in Asheville. She used to come to meetings when I was I used to plan things for the governor. The dean wanted to start a program added on the ends of the court. That’s the way lawyers used to study. You’d just… anyway. So, he arranged a scholarship for me to go over to Oxford, and I went over and studied English Common Law. Leila went with me. She got to travel and do things while I was in class. Then we came back to DC. Moved to Raleigh, and we’ve been in Raleigh since ‘77. When we got there, Leila took a job at WRAL, and I had a friend at the Supreme Court of North Carolina. He knew I’d studied at Oxford. He called and said I need somebody to teach seminars to the judges. And I thought, well, it wouldn’t hurt to meet every judge in the state on a first name basis before I go out to make a living. I said, “Ok, I’ll come over and talk to you.” I went over and asked him, I said, “how long… he thought it would take six months. I spent eighteen months going around the state to every judicial… the state’s divided up into districts, and you have district court judges, superior court judges, court of appeal judges, and supreme court justices. And I did seminars… they had just passed a law about guardian ad litem where children would have people appointed to protect their interest in court, so that was the specific thing I was going around teaching the judges. Now my wife Leila is retired from Western, and she is a guardian ad litem but to answer your question Antioch University in Washington, UNC-Chapel Hill, St. Edmund Hall at Oxford. Luke Hyde 9 EM: Why didn’t you go back to UNC to law school because you worked so long in the state government that you couldn’t? LH: Well, I had been in state government, and the rates were good at UNC-Chapel Hill, but I grew up here going to school with enrolled members of the Cherokee. And I’ve done a fair amount of reading about Native American law. So when I started… we didn’t have google at that time. We didn’t have a computer, of course, but I’d do my research in books and so on. I wanted to go somewhere where there was an emphasis on Native American law. So when I narrowed it down, it came down to just three or four places in the country. At the time, there were fewer than 1,000 Native American lawyers in the country, and I didn’t think well of that. A friend of mine I went to school with… the families at Cherokee wanted their children to get a better education would send them to school here. The only two high schools in the county… Cherokee High School and Swain High School. Swain was not perfect, but it was far better than Cherokee. My friend, Woody Sneed, is Cherokee… still living. Became the first Cherokee Indian of the Eastern Band to finish Harvard Law. This was is in the 60s. His sister Sarah became the second to finish Harvard Law in the 80s. She now works with the hospital at Cherokee. So a lot of my friends were Native Americans. I played ball with them. I played ball against them and so forth. And when I started doing research, Antioch was one of the few places that emphasized Native American law. I went for an interview. You couldn’t get in Antioch unless you went for a personal interview. I found out how much the deans were emphasizing Native American law, so that’s why I decided to go there, and I ended up working… every student at Antioch had to work with his professor on a particular topics. I ended up working with the dean because my brother and his father had worked together. And we sort of setting up programs for Native American law all over the country. And within a few years, we had a few Native American lawyers all over. But that’s why I ended up going to Antioch over UNC-Chapel Hill. LM: What made you want to become an attorney? LH: Several reasons. I grew up poor. The lawyers that I knew at the time were not poor. Secondly, it still gets my goat when I see injustices done. As a poor person, as a person who couldn’t speak correct English, as a person who came from a family not well educated, I observed these things that took place, and I got into student government when I was a freshman in high school partly because of that reason. I ended up representing other people in high school, things that happened. When I was at Western, I said I served two years as student body president; I ended up representing the people so… and my brother Herb had become a lawyer I could talk with him. I told you I grew up in a house without electricity and without running water. Herb would show up at the house… we didn’t have a phone, so he couldn’t call. He’d show up at the house and say, “Son, you want to go to court with me?” “Yes, sir.” I’d get in the car; we’d go to Jackson County or Clay County or Hayesville. He’d say, “Now, you go sit right there.” I’d go sit down on the bench. I looked at all the lawyers were men. There were no women lawyers in these western countries. When you live on a farm, you grow up on a farm. If you work, you get dirty. You know I learned to plow, milk cows and this… You get dirty. So I go down and sit down I look up there here were lawyers with coats and ties and clean white shirts and they were clean. I thought you can do that and make a living? (laughter). So there were several things. The influence of my brother Herb. My disappointment at seeing injustices done and realizing you can’t fight back unless you have an education. I started reading… my brother Herb when I was eight, went up to NYU. He finished at Western in ‘51. He went up to NYU. He was up there from ’51-’54. Before he… oh. I grew up in a house with two books. The King James Version of the Bible and Shakespeare. If you can have one or two, that’s Luke Hyde 10 two pretty good ones (laughter). When I was about seven and a half or eight… my mom was a reader. She read lots. My mom said, “Son when you’ve read every page in the King James Version of the Bible, and when you’ve read all of Shakespeare, I will take you to the public library.” I said, “What’s that?” She said, “Well, you can check books out.” I said, “Holy moley.” You can check books out and take them home?” So I started reading. Year, year and a half later, I said, “Mom; I started the first page of the King James. I’ve read it all. I’ve read all thirty-seven Shakespeare plays. I’ve read all his sonnets. I read everything he wrote.” She said, “now we’ll go to the library.” She took me to the library. It was like a kid in a candy store. They had about 25,000 volumes. I looked into it later. Mrs. Casada and Lawyer Black’s wife, were the librarians. Lawyer Black was one of two lawyers in town. And I had an ambition of reading every book in that library. My reading focused on legal things, history… I’m a history buff, and . . . Back to Herb. When Herb was going up to NYU in ‘51, he came to the house, and he had a box of books, and he asks, “Mom, may I leave this box of books here?” And he says, “Son, you can read them if you want. It was a set of Funk and Wagnalls Encyclopedias. Funk and Wagnalls is not a very good encyclopedia, but if it's all you got, it's pretty good. And in that, he said, “I want you to read this book,” it was a big [thing], I was a little guy. And it was H.L. Mencken’s, The American Language. H.L. Mencken was one of the brightest people that ever lived. He was in Baltimore. If he were living today, he’d be all over the right-wing. But anyway, he was a left-wing liberal crazy, and his American Language influenced my approach in life because first, he was a marvelous writer. He did not like injustices. That book influenced me, and I still read H.L. Mencken. As a matter of fact, if you don’t mind, I know I’m talking a lot. Let me give you a little quote. Mencken wrote for the Baltimore Sun. In 1919 he wrote an article in which he said, “the office of the US presidency seems to capture the imagination of the American people. One of these days in the future, the plain people of America will get their hearts desire, and the White House will be occupied by a moron. (laughter) I quote that lots today. (laughter). We are there. But you see why I like H.L. Mencken. I became a lawyer because I don’t like injustices. I want everybody to be treated with courtesy and respect. I want everybody… I carry… I usually have a coat. I carry the U.S. Constitution in my pocket every day, seven days a week. I read it frequently. There was an article, Lucy; recently, I read the papers fairly carefully. There was an article in the Asheville paper a week or so ago in which a gentleman wrote in quoting two verses in the Bible. And he said some things about heaven could not…certain kinds of people couldn’t go to heaven. Of course, the Bible doesn’t say that at all. And I thought about challenging, I said, “No.” If you argue with a fool, passerby's won’t know which is the fool. So I’m not going to respond to his letter. But I did lookup. I read the Bible numerous times. I looked him up, and he transposed, or he simply said a thing that wasn’t true. So I don’t like people getting their facts wrong. I don’t like people... I don’t like dishonest people. There’s no excuse for telling a lie. That’s a long answer but the things I read as a lad they influence… my brother Herb. The influencing books that my mom recommended I read. I read every page of the Funk and Wagnalls Encyclopedia from front to back. Because we didn’t have many books in the house and again it's not a very good encyclopedia by today's standards but if that’s the only one you got and so on. I’m a history buff, and I’m a memory freak. When I give talks to youth groups, I ask the group, I say, “How many can name all the US Presidents in order starting with the first one”… not one hand goes up. I say, “How many can count to twelve?” Everybody’s hand goes up. No, not 12. How many of you can count to 8? I say, “Well, in the next twelve minutes, I’m going to teach you eight sentences, and you can remember all the Presidents in order. I’m fascinated by the office of the presidency, and I read [inaudible]. The first sentence is in Washington, Adam was jeopardized by mad monster. Adam and Jack ran to the bureau, but in their hurry they broke a tile or poked a tailor and so on. An old lawyer from England came to this country in Luke Hyde 11 the thirties to teach the FBI, and he started that system, but he stopped because that’s a long time ago. I simply finished his system. And a rose taffeta dress will hardly be the right thing in a college; but whoever desires rose veils may truly wear them. I was in a [inaudible] buying candy for John’s son Nick whose Ford tractor was carted away by ray guns from behind the bush and so on. So I’m a memory freak. When I… six years after I finished at Western and worked for two governors, they asked me… Western was independent then and not a part of the consolidated universities. So Governor Moore had started the plan, and Bob Scott continued it. Governor Moore was governor from ’65 to ’69. Bob Scott was elected in ’68 and served four years. Back then, a governor could serve only four years. They ask me to come to Western and help ease Western into the consolidated university system. They gave me the… back then, the head of Western was called the president before we went to the chancellor system. The president was Alex Pow. Dr. Pow asked me to take the [idea] of the system to the president and do the things we had to do to bring Western in. We’d go to meetings… Dr. Pow was almost blind. He wore big thick glasses, and he couldn’t see very well. So he would ask me to identify the people there. So if there were twenty-five people there, I’d identify them. If there were fifty people there, I’d identify them. So I’d go in a crowd of people, twenty-five, fifty, seventy-five people. Give me twenty, thirty minutes, I’d tell you every name there. Anybody can do it if you want to. EM: Really? LH: Anybody. The brain is composed of about 100 billion cells. We use about 10%. What’s the rest of the thing for? This bright lawyer from England named Bruno Fürst, F-ü-r-s-t wrote a book about memory. I got a hold of that book as a youngster and I read every book I could find about how to improve your memory so I can tell you where I was on April 15, 1971. I can tell you every person in the room, but anybody can do it. See, if you do that, people will think you’re smart, whether you are or not. (laughter) If I go to Murphy, Cherokee County. Before I go, I go to my 3x5 card notes. I look at the 3x5 card at the names who attended that meeting, April 15, 1971, because I’ll bump into somebody. And the first thing they… Luke, what’s my name? So I’ve been doing that since I was a lad. Anybody can do it. When I was, I guess when the governor asked, Bill Moore, asked me to come to head the Regional Planning Commission in Asheville about ’66, 1966. And I was a member of the Jaycees. The Jaycees were bringing a memory expert from Greensboro or Summerfield, North Carolina, just north. And he was going to teach a memory course so the President wrote and said we need three or four more people to learn this system so we can go around and give talks to clubs and attract people. Naturally, I signed up. Fellow named Robert Nutt, N-u-t-t-. He was a nut. But he made himself a multi-millionaire by remembering what the stock market was doing. He played the market. So he came to teach this course. I took his course. A few weeks later, he called me. He said, “Son, can you come down to Kinston? I’m speaking to a Rotary club, and I want you to come and demonstrate. I’m doing a memory course there.” I said, “Mr. Nutt, I’ve got a job. I don’t think I can do it.” He said, “What’s your boss’s name?” I told him. He said, “what’s his phone number?” I told him. He called the boss, and the boss said, “Go help that guy.” So I got in the car and drove to Kinston, and we went to Rotary club. They had seventy-five members. We walked in. I stood at the door as they came in, learned everybody’s name, and during the talk, I called them all by name. But anybody can do it. People think it’s extraordinary. It isn’t, but Mr. Nutt had written a book. It was written in 1946, and I’ve got some articles downstairs. The New Yorker magazine ran an article about the guy from England, Bruno Fürst, and about Robert Nutt. This guy in Greensboro was acknowledged worldwide as one of the leading memory experts anywhere. So I worked with him. He went to Minnesota, and he called me, and he said, “Son, can you come up to Minnesota and help me Luke Hyde 12 teach a member course.” I said, “I don’t know.” He said, “Go ask your boss,” boss said go. So I drive up to Minnesota. But again, you can do it. You can do it. Anybody... if you want to. The brain will do what you tell it to do if you have faith in it and a big difference is a lot of people before they even get in a subject, whether it's academic or something else. Say oh, I can’t do that. That looks hard. Well, I’ll quit babbling. EM: I’m going to have to work on my name recall (laughing). LH: Well, when you get a chance, look up, Robert Nutt. Look up Bruno Fürst and get copies…you can find them. Read their things. Robert Nutt used a system. He would teach you certain keywords, and then if you need to remember something, you’d hang what you were trying to remember on that keyword. I’m given too long answers; I’ll try to be. EM: No. We want long answers. LM: So recently, you split your time between Raleigh and Swain County. Before that, did you live in Raleigh full time? LH: Immediately after law school, I finished at Western in ’63 and moved to Chapel Hill and was there for that year and that almost year of law school and then lived in Raleigh while working for Governor Moore and Governor Scott. Rented an apartment. I was single then. Yes. LM: Going back to kind of Swain County, why did you decide to buy the Calhoun House? LH: Because of a very good teacher. Your mom knows this, and you probably know it. Good teachers change lives. And if we’re lucky, they’ll be positive changes. I mentioned to you that as a lad, I was very shy because I didn’t know proper English. We pronounced words differently than town people did. When I was a freshman in high school, Mrs. Dehart was my teacher. Here they say Dehart. Instead of Dehart. A Navy man named Thad Dehart had been in World War II, and on furlough, he went to New York to see a play, and he met a model who became Mrs. Dehart. He started going out with her, married her, and brought her back. Fast-talking Yankee, my Southern ears could hardly keep up with her. She talked so fast, but she taught civics. Back then, civics was required. It was a ninth-grade class. Civics is the study of government and processes and systems and so on. And I was absolutely amazed by the woman and she, after a few days, asked me if I’d be willing to write for the newspaper, so I started writing for the newspaper. And I guess within two or three weeks from the start of school… oh. I left out. She walked around to everybody’s desk. Came to my desk, said, “Son, where are you going to go to college?” I said, “oh, Mrs. Dehart, I can’t go to college” because that wasn’t even on the radar. Thinking about… second day, she said, “Son, where are you going to go to college?” And I asked her why I better get with the program if I’m going to pass this course. (laughter). A week or two or three into it, she required of each student to write a paper and say where we’re going to college, what we’d study, and what we’d do after it. So I wrote this paper… my mom was working here then. I wrote this paper that said after high school, I would go to college, and I named two or three places… Western and a couple of others. And I would study history and political science, and I would get out and would work real hard and retire at 35 and own a small hotel. So mom was working here, and it seemed so I wrote this paper when I was a freshman in high school. Now I didn’t dwell on it a whole lot, but I took tax law I told you Luke Hyde 13 from Mr. Stewart Segal in Washington who was chief counsel for the IRS and studying tax law… bear in mind I’d been doing taxes since I was twelve. I noticed that in... the tax code takes up six feet of shelf space. And I’ve read the code many, many times. And there’s a little book about this big that’s got it summarized, and so I use that as a lawyer. I noticed that there are a whole lot of perks and benefits in the tax books for horse owners. My dad was a horseman. Dad was really good with horses, so I learned to ride as a child. When Leila and I met, our first three dates were on horseback. But anyway, I went to Mr. Segal, I said, “why are those so many benefits in the tax code for horse owners.” He said, “Luke, to understand any statute not just the tax codes, you have to look to see who wrote it and see where they're from. We’re still going in this country by the 1954 tax code. Now there have been changes, 2006, to be exact. But there’s still the basic law we go by. When I was in law school, I worked on Capitol Hill, so I learned a little. In Congress, tax bills must start in the House. They may not start in the Senate because the way the Constitution lined up, they start there. They pass and go to the Senate. So, Mr. Segal said look and see who wrote it and see where they’re from, so I did my research. The people on the tax-writing committee in 1954 were from Texas and Oklahoma. What do they have a lot of in Texas and Oklahoma? Horses. So they put all these benefits in. So, when I got out of law school and moved to Raleigh… Leila and I married at the end of my second year and bought Leila a horse for her birthday, and we still own a horse farm north of Raleigh. I started investing in real estate because I noticed that… oh, back to Mr. Segal. Mr. Segal was a fast-talking Jewish Yankee lawyer. Again, I had trouble keeping up with him. He had gone to Yale but in the classroom with him was a slow-talking Mississippi southern boy, Lester Fann, who had gone to Harvard. I could keep up with Mr. Fann. So, I went to them before we moved to Raleigh; I said, “I’m not making any money now.” Oh, at the time, the top tax bracket was 70%. If you made enough money, you sent 70% to the federal government. I wasn’t making any money. I went to them, and I said, “I’m not earning any money, but I think I’m philosophically opposed to sending 70% to the federal government. What should I invest in if I ever make any money?” And Mr. Segal said, “Well, Luke, let's go to lunch and talk about this. Let me get Lester.” So he called Mr. Fann. We went to lunch. They asked me a bunch of questions. I was… when I graduated, I was working with the dean on some Native American projects going back and forth to Raleigh. And after we had lunch, they said, “Well, you’ve answered the question, but we need to think on this a little. When will you be back in DC?” I said, “I’ll come back in a month.” Go and meet the dean on the property. We were working with a Native American named Wayne Whiteface out in the Midwest to get more lawyers… Native American into law. So I went back in a month, and they said, “Well, based on what you’ve told us, we think you ought to invest in real estate and horses.” So when I got to Raleigh, I started investing in real estate and horses. If you own enough real estate, the money you make as a lawyer, as a professor, or a medical doctor, may be protected. So I’ve been buying houses for forty-something years in Raleigh [inaudible]. I bought this for three reasons. One, to honor my mother. Number two, I thought it might be fun to run a B&B, and three, I knew Uncle Sam would help pay for it because the money I make as a lawyer is protected… knock on wood. I don’t owe a penny on this. I paid about a quarter of a million for it. Got it paid for. I’ve invested about $900,000. The last appraisal was 1.8 million, so this table where I do my taxes that’s depreciable. That sideboard is depreciable. That thing, this thing is depreciable, and I’ve got a list. So the way tax works is this. If I have money coming in from the law firm and I have a clock that’s depreciable that protects some of the money I made as a lawyer. So that’s why I bought it. LM: Do you like being an innkeeper? Luke Hyde 14 LH: No. I don’t like it. I love it and let me tell you why. I’d never heard of a B&B until I went to Oxford. They had B&Bs in England, Scotland, and France, and so on. Leila and I lived in a dorm while I was there, but on weekends, we’d travel. We’d stay in B&Bs, and I thought to myself, one of these days, I’d like to have a B&B. When I’m here, like the two professors you met a while ago, or the guy whose back in five or the guy who’s up in nine. They will say sometimes, “Well, my wife and I thought about having a B&B, or my husband and I have thought about having a B&B.” Michael, my friend, from [inaudible] said, “You know I might have B&B one of these days.” I said, “Well, you didn’t ask, but let me tell you. First, if you don’t like people, don’t have a B&B. You have to like people. Number two, if you mind being interrupted, don’t have a B&B. I always serve breakfast, lunch, or dinner three or four or six times. But if you go to a B&B, you’ve got to pay attention to them. And the third thing is if you can’t find good people to help you, don’t have a B&B.” When I first bought the place my older sister, Ilene, was living. I went to sis, and I said would you help me. I’m thinking about buying the Calhoun. And went to my younger sister Sue, I said, “will you help me?” They both agreed. I came up, signed the papers, got in the car, and went back to Raleigh… left them in charge. They hired people. We had a staff of ten. They’re five rooms, Lucy, on this level. Each with a queen bed, private bath, the professors [inaudible] number one. Thirteen rooms on the second floor, nine of which have private baths. Four rooms on the third floor with one bath. Total of 22 rooms. We rent twenty. If every bed is taken at twenty rooms, we can sleep fifty-four people, and there are times when we have fifty-four people. When I first bought the place twenty-two and a half years ago. We tried to rent every room every night because I could make more money coming in, and then I started noticing if you’ve got fifty people in the building, you can’t give good service. Even with the full staff. The ten staff members worked fine most of the year, but a couple months, they were standing around with nothing to do. So through attrition, we’ve gone from ten staffers down to three full-time and three part-time people. We’ve got two young college women who live on the third floor now, and they help. They’re off on a trip right now. They’ll be back in a couple days. My sis helps, my wife helps and as I say we’ve got three full-time, three part-time people and it worked better. I don’t try to rent every room every night, but I do enjoy it, and I’ll tell you why. I’ve never yet met a person from whom I couldn’t learn from. You learn something. I don’t talk all the time, like I am now. I usually try to listen to our guests. We had two young women from China. Their English was almost perfect. The doorbell rang one day, and I walked to the door… two attractive women were standing there. They said, “Do you rent rooms?” I said, “Yes.” They said, “May we see it?” “Yes.” They came in. I showed them. They said, “How much?” I said, “This room rents for ninety-five with tax $110.” Their faces fell. I said, “What is it?” They said, “Well, we’re working for Bojangles, and they put us up in a room. These two young women from different provinces that have never met. The U.S. State Department has some sort of agreement with other countries where people can sign up in their country… if they’re college students. They have to be college students. They come here, and then they pick companies to work for, and these four young women who had never met signed up to work for Bojangles in Bryson City. So they came from provinces of maybe 2 million people to a little town of 1400. And Bojangles put them up in a run-down motel. Four women in a room that doesn’t have enough room to turn around, and two sets of bunk beds and they said, “We don’t have room to turn around.” And they didn’t know the people before. So when they came to the door, I showed them, and they didn’t like the price. I said, “Well, my wife Leila is not here. When she comes, how about I come see you? So what shift you working at Bojangles?” They told me. Leila came, and I told her the story. Leila was working on the ugly back building. That used to be Granville Calhoun’s house built in the 1800s. Before I bought it, they built that ugly structure around it. And there used to be three apartments there. Leila had worked on fixing the Luke Hyde 15 first apartment. It was about 80% finished. So she said, “Let's rethink that.” So we go over to Bojangles, and I asked for the young women, and they came up. I said, “What time do you get off?” They said, “Four o’clock.” I said, “Can you come back over to see us after [inaudible]. I said, “Leila wants to show you something.” They said yes. So they came over. We went back there. It wasn’t finished. It was 80% finished... had a living room, had a kitchen, had a bathroom, had two bedrooms. Wasn’t finished painting, but better than a room where you can’t turn around. So when they came, we showed them, and they said, “How much?” And I said, “How much is Bojangles paying for where you are now?” “Well, there are four of us in the room.” They’re paying $75 per week for each person. I said, “well, how about $75 for the week for the two of you?” Oh, their faces lit up. They spent the summer with us. I had a bunch of bicycles out back. I took them to the bike shop. Got them up-fitted. I said, “Would you like to have bicycles?” “Oh yeah.” So we provided those. They had their cars, of course, to get around. Leila and I took them to Biltmore Estate. We took them around. And oh, they both were, as you might guess, heavy into computers. The mother of one of the young women ran a motorcycle shop in China. They have a lot of motorcycles, motorbikes. And we sat at the cash register over there, and she pulled her family upon the… you know where we could see each other, and we met the family. That other young woman pulled up her grandparents. We met them. And they took names in Chinese are very difficult for Americans to pronounce, so they took the names of Alex and Sharon Hyde. And we’ve been exchanging emails now…that was three years ago since they were here. We’ve been exchanging emails with Alex and Sharon Hyde. One of the young women is thinking of coming on and getting her doctorate. We said, “Well if you do, let us know. We’ll have a place for you. We’ll do what we can to be helpful. There’s a thing hanging on the wall over there… the grandfather… you can’t see it because of the door. The grandfather of one of the young women does calligraphy. In Chinese, you read right to left. And I’ve been reading Chinese philosophy, oriental philosophy most of my life, and Confucius is one of the greatest people who ever lived in my opinion. And that has a quote from Confucius, but it says something to this… they sent me the translation. It says something like, “some houses are good, some houses are evil. The Calhoun House is a good house, and we thank you for showing hospitality to our grandchild. And then it’s got a quote from Confucius about good houses. We had a professor from New York come here. He teaches Chinese, and he read it, and it was very close to the translation they sent me. So, the reason I enjoy being an innkeeper is that it’s a learning situation, and we can provide a place for weary travelers. The people, the two professors you met, are regulars; they come two or three times a year. Usually, stay three nights and walk. Old man back in number five usually comes two or three times a year. He’s promoting… he wants to start a Cherokee festival or something, so he comes here and goes back and forth to Cherokee. So, I like being an innkeeper. I love it because it’s a learning situation. LM: So I read that there used to be lots of meetings and conferences at the Calhoun House. Does that still happen? LH: It does still happen. One reason I put the word historic on the inn. When I bought the place, it was called the Swain Hotel. We’re in Swain County, as you know. I wanted to go back to the Calhoun name. Granville Calhoun’s daughter was still living. She was ninety-four years old. The lady who was a friend of my mother, who called mom to come over and work. So I made an appointment. Went to see Miss Pauline and talked with her, and I said I’m thinking of buying the old Calhoun. I says, “if I do buy it, would it be ok with you if I go back to the Calhoun name?” Now, I didn’t have to ask her. Under the law, I could do it. But I thought as a courtesy I should ask her. So she said, “Oh yeah.” I printed out something to sign, agreed to it. I went back to the Calhoun name, and I put historic on it because when the Great Luke Hyde 16 Smoky Mountain National Park was being planned, meetings took place in our dining room. There were very few… there were no hotels at the time other than this. There were no conference centers. Now, if people have a meeting in Swain County, they go to the courthouse or a church or here. Later, when the TVA Fontana Dam, pictured there on the piano, that you may not know this Lucy. But the TVA Fontana Dam was part of the Manhattan Project. Most people do not know that. The history books are devoid of it. But what happened is this. My grandparents on both sides lived in the northern end of the county. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, the next day the President of the United States, FDR, called George Norris who was a U.S. Senator from out in the Midwest. Norris had been promoting hydroelectricity and flood control. The president called him and said, George, told him what was going on about the attack on Pearl Harbor. He said, “I want a place where the enemy won’t find it, and I want a place where the media won’t find it.” And he says, “I think we’ve come up with a place,” and it was Oak Ridge, Tennessee. They ended up with a hundred scientists, and my friend later worked with him that was working with the government offices. A fellow who graduated from NC State was twenty-two, twenty-three years old. He had a hundred scientists under his supervision at Oak Ridge. A blooming genius. He had majored in chemistry and physics, and he was a bright man. So, they started the project to build Fontana Dam. My grandparents had to move out. The whole project was started and finished in less than thirty months, and that was to generate electricity for Oak Ridge, where they were working on the bomb. They had a hundred scientists. The people were sworn to secrecy. A husband could not tell his wife what he was doing. A wife couldn’t tell her husband what she was doing. They had different facilities for Caucasians and Black people. They’ve been some books written that called either the girls or women, Atomic City. Leila read the book. I didn’t. But Leila said the black women had to walk two or three miles to go to the bathroom. The white women just went around the corner. Racism was… but anyway, the buildings historic. When the Cherokee group… when the people wanted to start the Cherokee Historical Association that developed the drama and the Oconaluftee Indian Village, meeting took place in our dining room. So the reason so many things happen there aren’t a lot of places to meet. And we like people to use the room because we like to get people in the building. On Saturday, June 29, we had people from Raleigh and Winston Salem and Buncombe County and these western counties. Rodney Maddox is a chief deputy secretary of state. He’s originally from Swain County. He runs the department while secretary Wayne Marshall is out politicking. Rodney and I started a political discussion group twenty-five or thirty years ago. They were here, and we spent all day Saturday talking politics and how to win in 2020. So, it’s a neat place to meet. It’s always been that way. Does that answer that question? LM: Yes, sir. How would you say Swain County has changed throughout your lifetime? LH: How have I seen it changed? Is that… Well, one of the… after one year of law school, and before I went back to law school, I was a regional planner in Asheville for Governor Moore and Governor Scott. So, I learned a little about demographics and how to plan, and so on. One of the changes is there are fewer farms. Interruption ---- Have a good one…. You bet LH: …fewer farms. A few more people go to college. When I was a lad, not many people went to college. Thirty percent of people in Swain County today do not have internet access. Thirty percent. A lot of the youngsters have opportunities to go to school. More going on to, but it is still a very small number. The Luke Hyde 17 Qualla Boundary is technically the Cherokee Reservation is technically not a Reservation the way other Reservations are around the country. The Cherokee people bought the land and deeded it to the government. Every other reservation in the country, the government gave the land in trust to the Indian Tribes. About half the Qualla Boundary is in Swain County, which means the health of the people of Cherokee is not good. Unless something changes within about fifty to seventy-five years, there will be no Cherokees left because of diabetes. Seventy or eighty percent of Cherokee people are not only overweight but obese. Alcoholism is ten times what it is with the rest of the world. Drug abuse is fourteen times what it is with the rest of the world. The DNA of a Native American… it’s not just Cherokee. A Cherokee, a Sioux, a Comanche. The DNA does not have the capacity to reject the negative effects to reject the negative effects of alcohol or drugs, so the DNA is really different. My friend Woody Sneed, the first enrolled member of the Cherokee that graduate of Harvard law, is a hopeless alcoholic. He’s a working alcoholic. I’ll see him at ten or eleven o’clock in the morning and be drunk. But the people where he works, he’s a banker and a lawyer. They’re used to it. He functions, but he can’t stop. Now he’s made it a good while, but there are some changes. There are some changes. The other changes are these. More and more people come to Swain County from other places. It’s a small town. When I was a lad, the population was about 1400. I went away for forty years, came back. They got a population explosion here. They’re up to 1458 (laughter). But in summer and fall, the population doubles and triples because the people from Florida, Cleveland, Philadelphia, other places have built homes here. The county is… I tell you one thing that’s still common. The county is a very poor county because 86% of the land here is in federal or quasi-federal ownership. So only 14% of the land is taxable. And most people here are not well to do. The only well to do people that I know about are people who moved from somewhere else. The educational system is better than it used to be. It’s not perfect, but it’s good. I think the major change is that probably half or more of the businesses are run by people who grew up other places. Those are some of the changes. LM: How did you meet your wife? LH: Well, that is a good story and a very pleasant story. Brings a smile to my face. I had at the request of Governor Moore come up to Asheville. He asked me. He said, “Son, we’re going to set up a regional planning commission under the Appalachian Regional Commission, and I want you to go up and get it going. I said, “Governor, I don’t know anything about planning.” He said, “you don’t have to. You know people. You hire the planners.” He says, “you know how to work the people.” And so I came up… five counties at the time. Buncombe County, where Asheville is. Buncombe, Haywood, Waynesville, Clyde, Canton, Henderson, Hendersonville, Flat Rock… Madison, where Marshall and Mars Hill are located. And Transylvania. So it was five counties. They have since taken Haywood out and put them in with these western counties. These far western counties were so small they didn’t have enough people. But while I was there as director of regional planning, I had five counties. We had three commissioners from each of the five counties from both political parties. The chairman at the time was a member of the opposite political party of mine from Henderson County. A radioman. We had meetings monthly, and I made it a point if media showed up, I always had a piece of paper that summarized what was happening that day and the names of the commissioners of each county and the names of the staff. I had a small staff of four or five people. I had a young man working with me at the time, Ronald Wells, and

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Luke Hyde is interviewed by a Smoky Mountain High School student as a part of Mountain People, Mountain Lives: A Student Led Oral History Project. Hyde operates the Calhoun House in Bryson City, North Carolina. He discusses growing up in Swain County, his education and career path as a lawyer, his work in politics, the Road to Nowhere, and the joy he finds in running a bed and breakfast.

-