Western Carolina University (21)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- George Masa Collection (137)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2900)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (422)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6797)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (153)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1463)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (2008)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2929)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1944)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (195)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1680)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (556)

- Graham County (N.C.) (238)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (525)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3571)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4917)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (35)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (13)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (216)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (135)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (982)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (78)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2185)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (86)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (3)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (185)

- Envelopes (73)

- Exhibitions (events) (1)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (815)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (6090)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Notebooks (8)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (5)

- Portraits (4568)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (181)

- Publications (documents) (2443)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Relief Prints (26)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (1)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (18)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (462)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1482)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1923)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (190)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (111)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (2012)

- Dams (108)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1196)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (46)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (119)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (9)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (72)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

Interview with Manuel Briscoe

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

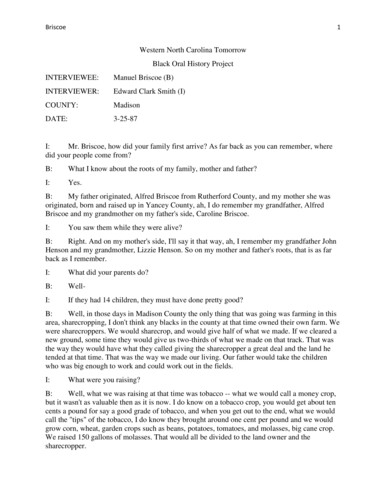

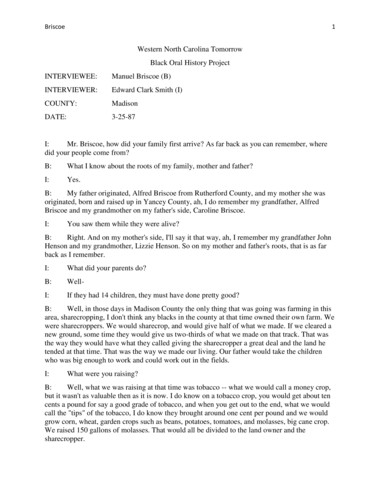

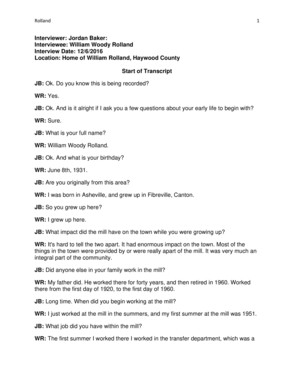

Briscoe 1 Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project INTERVIEWEE: Manuel Briscoe (B) INTERVIEWER: Edward Clark Smith (I) COUNI'Y: Madison DATE: 3-25-87 I: Mr. Briscoe, how did your family first arrive? As far back as you can remember, where did your people come from? B: What I know about the roots of my family, mother and father? I: Yes. B: My father originated, Alfred Briscoe from Rutherford County, and my mother she was originated, born and raised up in Yancey County, ah, I do remember my grandfather, Alfred Briscoe and my grandmother on my father's side, Caroline Briscoe. I: You saw them while they were alive? B: Right. And on my mother's side, I'll say it that way, ah, I remember my grandfather John Henson and my grandmother, Lizzie Henson. So on my mother and father's roots, that is as far back as I remember. I: What did your parents do? B: Well- I: If they had 14 children, they must have done pretty good? B: Well, in those days in Madison County the only thing that was going was farming in this area, sharecropping, I don't think any blacks in the county at that time owned their own farm. We were sharecroppers. We would sharecrop, and would give half of what we made. If we cleared a new ground, some time they would give us two-thirds of what we made on that track. That was the way they would have what they called giving the sharecropper a great deal and the land he tended at that time. That was the way we made our living. Our father would take the children who was big enough to work and could work out in the fields. I: What were you raising? B: Well, what we was raising at that time was tobacco -- what we would call a money crop, but it wasn't as valuable then as it is now. I do know on a tobacco crop, you would get about ten cents a pound for say a good grade of tobacco, and when you get out to the end, what we would call the "tips" of the tobacco, I do know they brought around one cent per pound and we would grow corn, wheat, garden crops such as beans, potatoes, tomatoes, and molasses, big cane crop. We raised 150 gallons of molasses. That would all be divided to the land owner and the sharecropper. Briscoe 2 I: Did you get paid, did he give you any money? B: Only pay you got working with a sharecropper was after you got your crop worked out or harvest in, if he had extra work on the farm for you to do during the year. See, he would keep what you call "books" on it. See, every hour that you would work for him during that year and the time came for him to settle up, go to the man's house and run the books up and whatever he owed you, that's what he would pay you, only what you did for him besides what you worked in your crop. That was the money part, maybe sometime outside of that you could go to some other guy, farm and help them on their farm and get a little income that way. I: Did you move around? B: Yes, in those days, you know how it is, sometimes the land owner and you might have a little hassle. I: What would you most likely hassle with them about? B: Well, really since my father was in charge, I wouldn't know the big deal would be. Anyway, if they had what we would call "falling out", you know, a man would have a little get up and go about them and say, "I will go somewhere else." You know what I mean. Alright, you go over yonder and rent from another guy. Maybe for about two or three years and whatever, then, if you didn't get along over there, well, the same, you would move somewhere else. Well, the same, you know what I mean. For that way you might have lived in five or six different farms in a period of time, you know. I: How did you feel about that as a young boy, you know, having to do the work, what did you think about it? Did you want to farm when you grew up? B: No, I didn't. You know all youngsters don't like that hot work out there digging in the big fields of corn, cane, tobacco, and the sun shining and you're about 10, 12, or 15 years old. You just don't cut it. You had rather be doing something else. But since you had a task master, say like my father was. I: Was he stern? B: He sure was. What he said was law and gospel. He rode his family with an iron hand so to speak, you know, in other words, you did what he said. We didn't like it too good, but it was one of those things that we had to do it. We were in the family and he was the man of the house. He went out there and made plans, got things planned out and ready. He would look for us to help him and we did through all the years farming and whatever there was to do on the farm. So that's the way it was in farm life with us there. I: Growing up as a young boy, what were some of the social conditions, like with children first? How did they get along with moving from farm to farm? B: Well the children, we got along fine. Now, most of the time we'd live on a farm were there were White families on the farm with children and we got along fine. They weren't any resentment, so to speak, with the families that was on that farm. The White and Black children, our family in those days would help one another, what we would call “swap work.” In wheat harvest time, our family would help the White family cut Wheat. They would help us take care of our wheat crop, so they weren't any problems. Hardly any resentment. We just worked Briscoe 3 together as poor Black and poor White men. We just worked together on the farm and put up the tobacco, that's one thing about when you got an acre or two of tobacco, you had to have more than one or two men to help run it in the barn. The Black and White family would work together to help take care of the tobacco, wheat or whatever like that. I: Did you attend school? B: Yes, I did. Our school at that time was out on what we call now, Long Ridge. I lived right at this old abandoned school building. But now we named it the Joe Anderson before we integrated elementary school on the last. And, at that time, this school went to the seventh grade. I repeated the seventh grade and that was the end of school for me. Wasn't any high school, integration, wasn't no school to go to. So, that's as far as I had gone to school to get an education. My older brothers David and Umphrey, there in those days when you had the larger children of the family, the father looked to them to help do the work. They didn't put any emphasis on education - only work. If he was big enough to work on the farm, plow a horse, use a hoe, mattick, pile brush, they put emphasis on staying home and working instead of going on and getting an education. Those boys there, David and Umphrey they did, I don't think they hardly finished the third grade. I: How did you get around? B: Within a five mile radius of Mars Hill, if we need to come to town, we come in a wagon. The mills was around town here, we'd sell a bushel or two of corn and put it in the wagon or throw it across the wagon and ride over and get mill ground. I: How long did it take you, well, I drove from Marshall here and it took me about ten minutes, how long would it take you all to come that distance on a wagon? B: Well, we wouldn't have to run to Marshall, we just come from four or five miles over the way into Mars Hill. We would say thirty minutes a little more by riding a mule or wagon. I: Was your family a religious family? Was your mom and dad religious? B: Yes, they were very religious. I: What church did you go to? B: We only have the one church here in Madison County that is Mount Olive Baptist Church. It was established in 1917. But, as I noted, my father was raised up Pink [Fork] area, just over the way what we call Walker Branch. There was a church over there for Blacks and some of our kindred is buried over there. But, as the people kept drifting into the Mars Hill area, this church out here got established. So a cemetery church and everything is here in Mars Hill. I: Do you remember as a young child growing up any customs that they had in the church then that they don't have now? B: There's very little difference in the church service, the customs and whatever, there's very little difference in now and then. One thing I do note they had years ago when I was a small boy about 8-10, they had what they called the BYPU they had it on Sunday evenings around 2 o'clock. I remember that well. I: What was it for? Briscoe 4 B: It was taught kind of like Sunday school quarterly, mainly to the young men and boys and of that nature, now that was the only thing we don't have now that I can remember that we haven't kept up with till this day. I: Did the church celebrate holidays? B: Well, the only thing our church celebrates now is homecoming, maybe such as men and Women days, and annual visitation days of other churches, set days they would come and we would worship together. So on, and like that. Other than that, it's the only thing the church celebrates is our homecoming and annual visitation day. I: What was your favorite holiday? What was Christmas like for you? B: Well, now Christmas, I guess I would say it was the favorite in my childhood days. Back then, when Christmas come we was looking really forward to it and it had a stronger, more of a meaning to it whenever it got there. Just as an example, you take today, a kid now can get as much right now as he could more than we got back in those days as Christmas. Whatever he wants between now and Christmas in way of a toy, he can get it. But back then, whatever we got was only as Christmas and very little at that. Maybe a banana, orange and apple, two or three sticks of candy. Parents wasn't fortunate enough to buy a lot of toys in those days like they do now. So I would say Christmas had more of a meaning and joyous feeling when I was small in those days that was my favorite. I: Do you remember any holidays that black people celebrated that White people didn't? Like remember some people say that they remembered when older people celebrated July 8th. B: No, I don't remember. I have always heard about July 8, but we never celebrated anything of that nature during my childhood even up through now around this county. I: What was the black leadership like when you were a young man, say 19 or 20 years old? Were there any leaders trying to speak out? B: In those days, when I were a young man coming up, ah, the only time that leaders in our community, I'm talking other than our church and those on the school board, Joe Allison Elementary School. I'm talking after we left and got to speaking out for integration, that's the only time the leadership in this community started, you know, speaking out, you know. But prior to that, the only leadership there was the deacons, the older men that look after the community and the church. They stood up and spoke out for that, they lived that. But that's the only leadership we had of black speaking out until integration. I: What did you think of integration? B: Well, it's nice. I said, you know, a few minutes ago about whenever I repeated the seventh grade up here, that stopped my school, that was it. So if integration had been on at that time, I could have went over here and got a high school education and eventually went out here to Mars Hill College. I think it is a wonderful thing, it sure is. I: In thinking about, now going back to your school, can you remember the first name of the school? Briscoe 5 B: The first name of our school was Long Ridge, that was the name. In the mid 50's they really wanted a name for the school, the Board of Education wanted a name for the school. That was a little before integration, so I was on the school board at that time and with two more. I: What year was this? B: I would that it was in about 1955 or '56, somewhere along in there named it the Joe Anderson Elementary School. Joe Anderson was the Black slave, now that's my wife's mother's uncle. He was a slave from over around Grapevine area, just up from Marshall. The Anderson that owned him was a trustee for the college and the first building they built starting Mars Hill College they didn't have, couldn't come up with the money to build, so they took Joe Anderson as a slave and locked him up and held him until his master Anderson, I can't call his first name, could get the money to redeem him. Joe Anderson name is in the college out here. He has a marker up the street here, Joe Anderson. So we named it after him, Joe Anderson Elementary School. My wife and her mother and her uncle worked through the college for years. They wanted some of Joe's ancestors to be a part of the college. My wife's uncle passed, her mother passed and now my wife is still working with the college. She has been there 39 years with Mars Hill College working in the cafeteria for them. Then, after a period of time went by, my daughter can go down there and get her education free, so she went and put in over three years down here in Mars Hill College where she is finishing up at Blanton's in Asheville. She wanted to get what she's taking over with so she's chose to finish up there. I: What is her name? B: Donna Briscoe. I: How many children did you have? B: Three, ah, my two older children live in Chicago, Phil and Thelma, and Donna after 18 years, she come along. When Thelma was finishing high school, Phil had done finished and was down here in Greensboro when Donna come along. So, hopefully, she will finish up here this spring and summer at Blanton's. I: This Joe Anderson, did they ever get him out? B: Oh, yes. They redeemed him and payed the bill. I: How much was it? B: Really, I don't know, I guess they have the record at the college somewhere, I don't know. It was payment on the first building here. So, Joe Anderson rings out here when they talk about Joe Anderson in the Mars Hill area. I: Do you think that things have gotten better in terms of, well in comparison to how you got along as 20 years ago versus how you get along today in Madison County, do you think that things are better? B: Yes, they are much better. Much better to what it was 20 years ago, 25 or all prior to that, I think it is much better. Another thing, we have plants here, we've got blacks working in the plants even just across the line in Buncombe County, the Blacks work in the plants, whereas 20 years ago or better than 20, there weren't any. See, that's a help to the blacks in Mars Hill area to have jobs they can go to and work just like other people. So things are better. Briscoe 6 I: Now Joe Anderson, that was quite a contribution. B: It was. I: He actually went to jail? B: He went to jail. I: Can you think of any other examples of things that Black people have contributed to in Madison County? B: No, I can't think of anything other than working and being decent people and, ah, living respectful among people and getting respect, I think that is a big factor we all have to play regardless of who we are. White, Black or whatever, if we want respect, we've got to give it. I worked here for the city. I: How long have you worked for the city? B: Well, I retired in 1984, I worked for the city 34 years and 2 months. When I came here, I was the only employee and one policeman. The town fathers, all the town people were nice people in town here. They would leave it up to me to carry on the work, whatever is to be done, ah, installing water mains, they would call me in and ask my opinion about the water works and all. They would say, ''You go get the help." So I would go out and get the black boys who didn't have any work to do. We'd come in and work two or three weeks at the time, work together, and I respected everybody and their property or whatever or wherever we were at. That way, people respected me, all over town they would say, "See Manuel", so and so, well, "Ask Manuel". I appreciated that so now. I: You got respect because you gave respect? B: Yes, sir. Regardless who it was, Black neighbors, men or women, I would respect them all, see. If it White, little boys or girls, I did the same. They gave me respect. So I appreciated all of them. I: Do you remember ever hearing any stories about your grandparents or your parents? B: Well, on my mother's side, but very little stories on my father's about my grandmother and grandfather. The only thing on my mother's side, her father was a banjo picker, he was a musician. Everybody delighted in hearing him play the banjo. They say around Christmas time they would gather up from house to house for a week or so and just have good clean fun. Maybe old time dancing and banjo picking. Now that's about the only thing that I can remember any tales or anything about my grandfather and mother on either side. Other than that we lived a good distance apart, and it was kind of hard to keep up with activities and things that would go on. I: Do you remember any historic events like floods, depressions, or wars, that affected your family? B: Well, I do remember the depression well. I can remember very well in 1925, there was a drought, just a plain old dry spell come through here in the summer of ' 25. It was really rough on the families, especially those that farmed. We had to go out of town to buy flour because the water than ran the mill wasn't any to pull a big wheel, you know. I remember, I never will forget Briscoe 7 it. You know a country boy, used to eating cornbread and biscuits or whatever; but when you get to one thing so long you get tired of it. I remember we ate a lot of biscuits that summer. Morning, evening, and night, and I was glad when they could go to mill and get some cornbread. I remember that well. And then I remember in the 1930's when the depression was on. It was a tough time, but my father was out there in the lead, he was a good provider, he could see ways to get things, do things, you know that as a child we couldn't do. I felt it, but he felt it more so because he was the father and the leader. I worked a many of a day for ten cents an hour, sure did. Finally it rose to $1.50 an hour. Then in the real early 40's, it rose to about $2.00 an hour. During the war, things began to be on the incline raising up there and I remember that well. The next things I remember, which it didn't affect us much, was a flood in 1940 came through just about wiped Marshall out. I: In 1940? B: Yes, I think they had one real bad one in about 1916 that just about took Biltmore out and Marshall, too, at that time. This one I can remember was in 1940. We got up on the bluff up there and looked over town at the court house and water was just running through all the buildings from side to side, you know. It really looked bad. Now, that was something that I will never forget what happened at that time. I guess that's about the only events I can remember is the flood, the drought, as a boy coming up. I: Can you think of anything else that you would like to tell me? B: Well, really, there isn't too much more to tell. Of course, the rest of the family is just like me. They're married, you know, off at work and have children, whatever. Just such as that, just trying to survive. I: Mr. Briscoe, in your opinion, where do things go from here for Black people as far as getting or being more visible and having more opportunities than they had in the past? What do we need to do to go further? B: Well, I think there is one thing we need to do, I think we need to have more voting and get men to go out and run for different offices and all that. I think that really is what we need to work on, getting men in the office and legislature, you might say or even congress or senator, or whatever. Get our men to work in places of that nature. I think that is what we need to do and everybody come out and vote and support the people that we want in these various places. I think that is the one thing we need to do is the black people and another thing I think, what Black people in general overall need to do, of course, I guess I may have a different attitude from others, well, I know I have. Now this thing of demanding and going out here and I'm gonna excuse me for the expression, I don't mean it like this, but you will catch what I'm talking about when I say it. "I'l1 go out here and I'll take me a 2' x 4 ' and I'm gonna do this and that." That ain't no way to get a hold of anything. I think what really what our leaders need to do for black people. We ought to teach more love and respect for our enemies if I can say it that way, you know what I am talking about. Have an attitude of cooperation, and getting along. I think if we get it in here and let that reflect out and they know it is, I think we can accomplish a lot that way because I'll be 68 years old in June and I have been around a little! All that I ever accomplished is by doing the right things, throwing out respect and so on like that. Then as just a common laborer and what I went through in the last 35 or 36 years, that's what brought me to where I am Briscoe 8 now, and what I have now. That's what we all should do and have that attitude. Because there ain't a thing you can do when you start fighting, nothing you can do. I: Mr. Briscoe, I thank you so much, it has been a real honor and a real privilege to sit here with you. B: Well, I enjoyed it. I hope it will be of some help to you. I: I'm sure it will.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Manuel Briscoe is interviewed by Edward Clark Smith on March 25, 1987 as a part of the Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project. Briscoe talks about sharecropping quite a bit in the beginning, church customs changing, excitement for Christmas as a child, black leadership, his elementary school being named after a slave, respecting everyone, local legislation, and more.

-