Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (24)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1295)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (1794)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2393)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1886)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (161)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1664)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (233)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (478)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3522)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4692)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (25)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (12)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (211)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (981)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2020)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (247)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (68)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (184)

- Envelopes (73)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (811)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (619)

- Maps (documents) (159)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (5735)

- Newsletters (1285)

- Newspapers (2)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (12982)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (5)

- Portraits (1657)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (151)

- Publications (documents) (2237)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (1)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (15)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Vitreographs (129)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (282)

- Cataloochee History Project (65)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1314)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1744)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (388)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (166)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (110)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (1830)

- Dams (95)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (60)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (917)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (154)

- Hunting (38)

- Landscape photography (10)

- Logging (103)

- Maps (84)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (69)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (245)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

Interview with Dan Pittillo

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

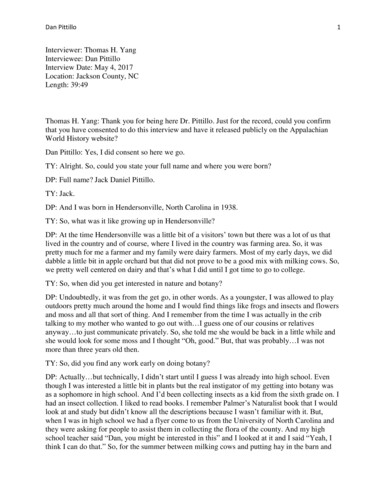

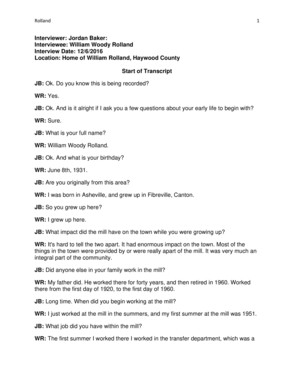

Dan Pittillo 1 Interviewer: Thomas H. Yang Interviewee: Dan Pittillo Interview Date: May 4, 2017 Location: Jackson County, NC Length: 39:49 Thomas H. Yang: Thank you for being here Dr. Pittillo. Just for the record, could you confirm that you have consented to do this interview and have it released publicly on the Appalachian World History website? Dan Pittillo: Yes, I did consent so here we go. TY: Alright. So, could you state your full name and where you were born? DP: Full name? Jack Daniel Pittillo. TY: Jack. DP: And I was born in Hendersonville, North Carolina in 1938. TY: So, what was it like growing up in Hendersonville? DP: At the time Hendersonville was a little bit of a visitors’ town but there was a lot of us that lived in the country and of course, where I lived in the country was farming area. So, it was pretty much for me a farmer and my family were dairy farmers. Most of my early days, we did dabble a little bit in apple orchard but that did not prove to be a good mix with milking cows. So, we pretty well centered on dairy and that’s what I did until I got time to go to college. TY: So, when did you get interested in nature and botany? DP: Undoubtedly, it was from the get go, in other words. As a youngster, I was allowed to play outdoors pretty much around the home and I would find things like frogs and insects and flowers and moss and all that sort of thing. And I remember from the time I was actually in the crib talking to my mother who wanted to go out with…I guess one of our cousins or relatives anyway…to just communicate privately. So, she told me she would be back in a little while and she would look for some moss and I thought “Oh, good.” But, that was probably…I was not more than three years old then. TY: So, did you find any work early on doing botany? DP: Actually…but technically, I didn’t start until I guess I was already into high school. Even though I was interested a little bit in plants but the real instigator of my getting into botany was as a sophomore in high school. And I’d been collecting insects as a kid from the sixth grade on. I had an insect collection. I liked to read books. I remember Palmer’s Naturalist book that I would look at and study but didn’t know all the descriptions because I wasn’t familiar with it. But, when I was in high school we had a flyer come to us from the University of North Carolina and they were asking for people to assist them in collecting the flora of the county. And my high school teacher said “Dan, you might be interested in this” and I looked at it and I said “Yeah, I think I can do that.” So, for the summer between milking cows and putting hay in the barn and Dan Pittillo 2 whatever else we were doing, I would go out and collect plants. I discovered the procedure that I needed to use required drying them and by that time we already had electricity because when I was born in ‘38, we did not have electricity until about ‘45. So, 1945 on. And in high school at about the time I was doing this, it was like in the mid-fifties and then we had the, already, milking machines milking the cows and the cooling refrigerator. Well, we called it a cooler…a milk cooler…in which we would keep the milk cool. And the heat from the milk cooler with the fan, I could set my dryer on and dry my plants. So, I started doing it that way and it was convenient. TY: How clever! So, is this what inspired you to continue your work in nature and botany as you went to university? DP: Well, I wasn’t sure. I went to Berea College because at the time Berea was an option that I really wanted to go in part because my high school teacher was a Berea graduate and he encouraged me in that direction. So, between applying at Western Carolina Teacher’s College and Berea College, Berea was my desired education area. So, when I got to Berea I thought maybe I would be in chemistry but it only took one semester to tell me “Nope, you’re not going to be a chemist. That is not your favorite thing” and so I was moving much more toward biology. And I got a project the fourth…no, third semester in which my mentor Hershel Hull decided that he would like me to collect plants in the Berea College Forest and I said “Great.” So, they turned me loose on five thousand acres of Berea College Forest and said, “Go to it and whenever you get finished in the evening, I’ll pick you up at point Y or X” or wherever it was. And so that’s how it went for my…well, essentially it was two and a half years. Collecting plants in Berea College Forest and around the University of Kentucky later. Worked with a professor there on a tree…a Yellowwood tree . . . the Yellowwood tree. Then I got my Master’s degree in Ecology and Distribution…Yellowwood and that finished my Master’s degree. Went on for a Doctorate at the University of Georgia. Got a Ph.D. working with radio nuclei fallout on the granite out crops and the woodlands adjacent. And so, I learned a great deal about radiation and how that affected organisms and became a part of the biochemical cycling within the ecosystem and so…I tell you, I deviated a little bit from strictly botany until I got into college here where I was teaching and it was impractical for me to pursue that because the nature of the project required experimentation that we were not going to get at Western Carolina. So, I went into field collecting and that’s how I have continued since the 1960’s until now. TY: So, if you don’t mind, me going back a bit. Could you tell me more about this fallout project that you were working on? DP: I went to the University of Georgia working with the professor who already had a project going in which he was collecting materials from the granitic outcrops in the vicinity of Athens, Georgia where we were located and he said, “I would like to have you do some project that relates to this.” And I said “Sure.” I had a teaching assistantship there where I was earning enough to keep me supplied with my financial needs but he wanted me to work with a project that he was doing and I said “Okay.” And so, I spent a little time trying to figure out what would work. And I came up with a project thinking that fallout is part of the trouble. In other words, it gets into the ecosystem here. It lands on the rock. The plants on the rocks are [unclear] or just not available or that don’t have enough nutrients available when the material that’s in the air falls out like dust or whatever. They can utilize the nutrients that are supplied through rain and through dust but also because fallout comes with it. And the fallout is a product of nuclear testing, both in Dan Pittillo 3 the United States and in Russia and I was able to detect that with the instrumentation we were using to differentiate the kinds of radio nuclides that accumulate in the trees. And that involved about nine different radio isotopes which we sorted out by this simulation counter and that allowed me to develop my project which wanted to compare whether the trees high on the outcrop which were more impoverished than those on the low or those in the woodlands which were nutrient supplied. And my prediction…my hypothesis was the trees on the top of the outcrop would accumulate more of the radio nuclei’s. Those at the bottom of the hill would accumulate some but not as much as those on the top and those in the woodlands would be least because they had more nutrients supplied from the soil. It turned out my hypothesis was partially correct. High on the outcrops, there was an intermediate accumulation level. The low outcrop was the highest accumulation and in the woodlands, was the least. And the reason for that is because as the rain deposits the material on the rock, it just simply runs down the hill where the lowland trees are. They then absorb through the root systems as well as from leaves and stuff that’s exposed to the atmosphere. And therefore, they accumulate more than the high outcrops that I had predicted. TY: Interesting. So, after you graduated college you decided to return here. Could you tell us why? DP: I wasn’t thinking so much of returning here because I was looking for wherever I could get a job. I got an interview offer in February of 1966 with the condition that if I came and they didn’t offer me a position, that they would pay my travel expense. So, I came up here. I went back…I didn’t get back very long before they said we accept you. So, I had to pay my travel this time but that meant that I had a job offer like February, before I graduate. And so, as quick as I got my Doctorate finished and graduated in…the dates are clear in my mind. On August 15th, I walked with my Ph.D. and August 28th I married my fiancé…my wife. On September 3rd, I appeared here for work. So, that was the beginning of my forty-year career. Or should I say thirty-nine and a half years. TY: So, what inspired you to become a professor? DP: Well, I had enough experience starting at the University of Kentucky with just teaching botany labs that I knew what was involved. I also knew that I liked to do it. In other words, I was interested in the subject material and so between just liking to do it and actually carrying forward with teaching, it was not that big of a step. So, I got teaching experience at the University of Kentucky for a couple of years. Three more years of laboratory instruction at the University of Georgia and then when I came here, it was just straightforward. TY: So, you’re the director of Western Herbarium I’ve read? DP: Actually, I was curator which is a little different. By definition, curator means you just are responsible for managing the collections. Director means that you manage and also you are involved with some compensation. So, the director now receives compensation. I think it’s a sixteenth of the salary goes to the Herbarium directorship. I was doing it for free…I guess you could say for free. At least it was extracurricular. TY: So, did you continue going out to collect plants while you were doing this or did that sort of fade away? Dan Pittillo 4 DP: Yeah, that just became part of it. Our department head, Jim Horton, at the time…the late Jim Horton. He just recently died May the 5th, and I decided that we were going to do a project together so we wanted to look for the plants that occurred on the mountain rock outcrops in comparison with those that were in the Piedmont of Georgia and South Carolina. So, we started that project and the result was that I got into it pretty much and also become interested in what was the nature of these rock outcrops. I mean, what is the value to us of those kind of unique plant communities. And so, I began to expand and work with natural areas. And I started that in the seventies and I have continued ever since. And right now, I’m working with the Great Smokies Park on their collections, trying to expand any species that we have overlooked. And luckily, we have picked up about…I think we’ve got somewhere in the neighborhood of a dozen to eighteen new species that were not known to the park. TY: Right here in the Smoky Mountains? DP: In the Smoky Mountains. I had done this a little bit on the Blue Ridge Parkway for a couple of years and I was kind of…what would you say, I was in the process of working with one against the other to see who had more species and then I worked with the others against the one I had just finished working with. And so, the balance is almost equal. Here, the Blue Ridge Parkway is extensive. Four hundred and sixty-nine miles of a strip that goes all the way from here in the Smokies to near…up to the edge of Skyland Drive which connects to Washington D.C. So, I have all that long strip of territory to work in. But the Smokies is a more compact, extensive area of the highest mountain range in the southern Appalachians. Or next to the highest. There’s a few peaks that are above those of the Smokies but as a mass, the Smokies are a much bigger mass. And also, the Tennessee side of the Smokies has been the project for the University of Tennessee and folks on that side for years and they mostly worked on the Tennessee side being handy. And here in North Carolina, we didn’t have as many going on now so what we are trying to do is fill in some gaps on the North Carolina side. The goal that we now have is that we’re looking for rock substrates that support a different flora on this side similar to those that are on the Tennessee side. The Tennessee side has a much greater basic rock than North Carolina does because of the fact that it’s pushed some limestone and other things up and about over there whereas over here, there’s mostly metamorphic rocks and there aren’t as many bits of limey deposits, and therefore, the kind of plants that can grow on those are not as numerous. But, we don’t know where they are. At least until that was done recently when geologists had done the new geologic map of the Smokies which includes North Carolina. So, then this past Saturday, we did an exploration from Fontana Lake up Buzzard’s Roost. And that was a pretty big effort because we’re going from like seventeen hundred and twenty-six feet, I believe at the lake to twenty-four hundred feet in elevation for Buzzard’s Roost and we’re climbing this cliffy portion that’s like almost forty-five degrees. And so, it’s not an easy trip. I don’t know…I have got to go back. But anyway, we’ve come out with a few new ones but I don’t know if we have new species for the park. We’ll just have to…that takes a while to check through the list and determine our collections. TY: Alright. So, going back a bit more…so the seventies saw the rise in the environmental movement and more interest in ecology and the earth. Do you have any experiences related to that? DP: Well, of course. You might say one does not find things taking place that is not discouraging if you’re interested in natural areas because wetlands have been drained or flooded with lakes. Dan Pittillo 5 That means that those kinds of places which support that group of plants is gone or if not gone, modified drastically. The rock outcrops that I was interested in…when we were working in Panther Town Valley that was one of the most…what you might call unique of the rock outcrops. Granite domes on a few of the mountain peaks of Panther Town Valley. And therefore, I was very interested in seeing that particular valley be maintained in its natural condition. It was scheduled to be developed into a condominium home site estate with the lake in the middle of the valley. I talked with the owners several times. Initially, they were very…not necessarily…not all the owners were antagonistic toward the idea because they wanted to have their investment repaid. But eventually it came down to the fact that it was either going to be the development or else. And so, they decided that they would offer it without development. So, they offered it at ten million dollars. I got into the fray. And which, I was saying “You know, we need to acquire it somehow.” But ten million dollars is not an easy thing to come by in the eighties when that happened and the result was that eventually it was sold initially to the Nature Conservancy after Duke Power had purchased a portion of it. Duke and I got into a slight disagreement on where the powerlines should go. Namely, they wanted to cut through the middle. I said “Don’t go through the middle of Panther Town Valley. Go through the sides somewhere.” But they did not intend to do that so they wound up putting it right through the middle. So, it now exists as a line right across the middle of Panther Town Valley. But, Nature Conservancy and they agreed and bought a portion that was not included in the Duke Power land. And that portion then was immediately transferred to the U.S. Park Service and the Park Service now own it. And because the Park Service is not funded as well as it should be, we now have developed - and I had nothing to do with starting this except encouraging it - with the Friends of the Panther Town. And the Friends of the Panther Town are the instigators in the…essentially the crew that sort of looks after trails, marks the trails, clears them and works with the Parks Service in an arrangement. And I’m a member of course, of the Friends of Panther Town. TY: So, recently or maybe not recently but you’ve been writing for the Sylva Herald. Did this decision (?) to write for it? DP: That came about…Georgia Ellison is a friend of mine who is a writer. He lives over in Bryson City. He says “Daniel, don’t you write for the newspaper?” and I said “Well, okay. I’ll give it some thought.” So, then I contacted his daughter who actually is the editor. And she says “Alright, let’s do it.” So, along about October of last year, I started a column and what I was going to do was essentially enumerate and describe some of the features of Jackson County. Now, many folks in Jackson County, whether they have lived here or they have immigrated here do not know about…they do not know where or what is…They know it’s neat. It’s a pretty county. It’s actually one of the most…should I say mountainous county that we have. Haywood and Jackson are probably closely related and neither of them have very much land so…But there’s a lot of nicks and crannies and cliffs and swamps and other things that are in this county. And so, what I decided to do was write a project that I had done in the early nineties for the county itself in describing the natural areas. And that’s how I came about with this series of columns. TY: And so, have you seen any effect that these columns have had with people? Have people come and talked to you about them? DP: Yeah. I don’t think they miss a chance if they know me. “Hey, I like your columns.” Well, actually, I don’t think anyone has ever told me they don’t like them but they wouldn’t. But a lot Dan Pittillo 6 of them would not be reading it because it’s not of interest. I mean, the columns of this sort…you know, it’s kind of…it reminds me, if you’re a New Jersey ghetto guy and you’re raised in New Jersey and you don’t have much contact with National Parks, you may want to say that I like the fact that the National Parks exist. “Someday I want to go see them.” Well, the same sort of thing happens here in the county. You think “There’s some nice places here and maybe someday I might like to see some of it” but it may not be possible. Some of the people that are…should you say confined to the home or sometimes the bed, they can’t go. So, they won’t be able to participate in. But maybe if they have had an experience of some sort, that was good, it will be…the column will be able to give them a sort of mental image that they can back up on and say “Yeah. We support this quality.” TY: And so, for the past few years, you’ve also been consulting projects like the Biltmore Estate as I’ve read…could you tell us about that? DP: Yeah. That was similar to the same sort of thing. I have been visiting the Biltmore Estate some years and I thought it would be nice if we knew what has happened to the collections that we bumped into in our herbarium. I looked in our herbarium here and I had I don’t know, maybe…a dozen or so plants that were marked. Biltmore collected in Biltmore…but I didn’t know what was behind this. And all those were like in the eighteen hundred and I’m thinking, “Well, has anyone looked at the plants that are there since then?” So, I talked to the managers and I said, “Would it be possible for me to expand this effort and look and see if we can find out what is here now?” And so, they said “Sure.” So, I spent about three years collecting over the…turned out to be about eighty-eight hundred acres of territory so it’s the same sort of thing I’ve been doing. And so, I did…I wasn’t interested in the plants that were being displayed in the gardens. But beyond the gardens, where the native stuff is or some of those that might have been displayed at some point in the garden have now naturalized and become a part of the flora. So, that’s kind of the angle I went at it and that turned out to be a good experience. I don’t remember how many plants I collected in there but I suspect it was like…at least two to three thousand. So, that’s a pretty good slice of new information that we’ve got on the Biltmore Estate that we would not have had if I had not done this. TY: And as far as the plants on display, have they naturalized into the native flora or… DP: Well, some of them have and some of them are invasive. There’s one we call the Christmas Honeysuckle. And I’d seen that on my grandparents’ home planted. I never thought much about it. It smells sweet. It’s called Christmas Honeysuckle because often it will bloom in either late in the fall and maybe early winter or later winter. And I didn’t know that it was naturalized anywhere until I got to Biltmore Estate and it’s a lot of it. So, it’s all over now. The woods. And of course, they had planted it at some point there. They also had planted Chinese Silkgrass. Well, that’s not a good one to turn loose here. So, it’s covering the woods. There’s another one that’s the celastrus orbiculatus which is Bittersweet and that ones used in decorative material for flower pot arrangements and so on usually in the fall. But the trouble is people have been gathering the material, using it for display, and then when they get finished with it, they just toss it out. And when they toss it out, it comes up. So, now we’re getting these vines all over, everywhere. And I don’t know if the Biltmore Estate had anything to do with it but they might have. TY: Has it been having an effect on the environment? Dan Pittillo 7 DP: Yeah, especially the folks in the Forestry dislike it very much because it just essentially covers the trees like kudzu. And so, it gives them trouble with the competition in the natural forest. TY: Do you know of any efforts to fight it? DP: Yeah, we tried. The trouble is the people that like it for the floral arrangements have won over the fact that they can continue to be in the trade. And so, it’s kind of economic value for the florist. And should I say that they have maintained the loudest objection to it being reduced or excluded from the trade and therefore spread more. But it’s going to be spread anyway. I have finally come to the conclusion that many of our…what we call invasive plants will become part of the flora. They won’t be recognized any differently than part of the flora in two hundred years. It will just be part of what’s here, no matter where it came from. TY: Interesting. So, do you feel there’s any way to expand awareness on these various issues? DP: Well, we continue to do that and there’s a cadre of folks that are very concerned about it. Some of the people that are concerned are not terribly…well, I shouldn’t say they’re not terribly…they’re not able to put up enough political clout to alter the direction that the economies are pushing. So, with Bittersweet there’s an example. How do we stop Bittersweet spread? We go out, we pull up the vines, we destroy the roots if we can but can we really stop it? The birds are our [unclear]. And as long as birds love the seeds and eat the seeds and spread it, it’s not going to stop. TY: So, how do you think we can pass on this tradition of ecology and love of nature on to the youth today like me? DP: I don’t know but you’re probably convinced already. I think it’s important that the information be made available and encouragement. If you start a young child to learn what nature is, how it works, and what works against it, then you’ll be doing the job that needs to be done. You’re a little further along in life if you’re not already convinced, you’re probably going to be hard to convince because you’ve got other things that’s more important. If you are really convinced, then you might be a leader with the youngsters and encourage them to learn more about nature and take them on field trips and stuff. That sort of…we’ve got to get the youngsters back into the…something besides the computers. And you might say the visual world alone and into the woods, where the things are real and where the organisms are trying their best to do their thing and that is to propagate themselves. TY: Is there any advice you have for the next generation of up and coming botanists? DP: Learn your ecology. Ecology’s a broad topic but you need to understand it. If you don’t understand ecology, you won’t understand nature very well. I mean, you can look at the flower and say it’s pretty, you can see a tree and say it’s nice and it’s useful but you’ve got to know the difference between what the flower is doing and what the tree is doing, in order to have a sense of what the world operates…or how the world…nature operates. The encouragement has to be from adult to child, child to child. TY: Alright. That’s all the questions I have. Do you have any final thoughts you’d like to say? Dan Pittillo 8 DP: No, but I’m glad you gave me this opportunity. I don’t know if it’s been of value to you but if it says anything to you than proceed in life and keep it as part of your understanding of nature. Thank you.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Dan Pittillo is interviewed by a Smoky Mountain High School student as a part of Mountain People, Mountain Lives: A Student Led Oral History Project. Pittillo has been interested in botany his whole life. He has collected and documented plants for Berea College in Kentucky, the Biltmore Estate, and in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and Blue Ridge Parkway. Pittillo discusses his doctoral research at the University of Georgia studying radio nuclei fallout and how it effects the ecosystem. He also talks about his work at WCU, which began in 1966, his role in the conservation of Panthertown Valley, and his recent writing for the Sylva Herald.

-