Western Carolina University (21)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- George Masa Collection (137)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2900)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (422)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6797)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (153)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1463)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (2008)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2929)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1944)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (195)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1680)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (556)

- Graham County (N.C.) (238)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (525)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3571)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4917)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (35)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (13)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (216)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (135)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (982)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (78)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2185)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (86)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (3)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (185)

- Envelopes (73)

- Exhibitions (events) (1)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (815)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (6090)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Notebooks (8)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (5)

- Portraits (4568)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (181)

- Publications (documents) (2443)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Relief Prints (26)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (1)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (18)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (462)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1482)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1923)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (190)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (111)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (2012)

- Dams (108)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1196)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (46)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (119)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (9)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (72)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

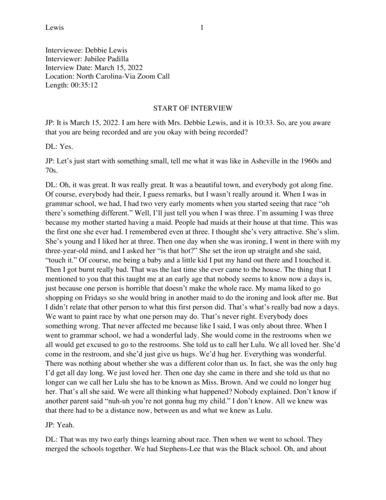

Interview with Debbie Lewis, transcript

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

Lewis 1 Interviewee: Debbie Lewis Interviewer: Jubilee Padilla Interview Date: March 15, 2022 Location: North Carolina-Via Zoom Call Length: 00:35:12 START OF INTERVIEW JP: It is March 15, 2022. I am here with Mrs. Debbie Lewis, and it is 10:33. So, are you aware that you are being recorded and are you okay with being recorded? DL: Yes. JP: Let’s just start with something small, tell me what it was like in Asheville in the 1960s and 70s. DL: Oh, it was great. It was really great. It was a beautiful town, and everybody got along fine. Of course, everybody had their, I guess remarks, but I wasn’t really around it. When I was in grammar school, we had, I had two very early moments when you started seeing that race “oh there’s something different.” Well, I’ll just tell you when I was three. I’m assuming I was three because my mother started having a maid. People had maids at their house at that time. This was the first one she ever had. I remembered even at three. I thought she’s very attractive. She’s slim. She’s young and I liked her at three. Then one day when she was ironing, I went in there with my three-year-old mind, and I asked her “is that hot?” She set the iron up straight and she said, “touch it.” Of course, me being a baby and a little kid I put my hand out there and I touched it. Then I got burnt really bad. That was the last time she ever came to the house. The thing that I mentioned to you that this taught me at an early age that nobody seems to know now a days is, just because one person is horrible that doesn’t make the whole race. My mama liked to go shopping on Fridays so she would bring in another maid to do the ironing and look after me. But I didn’t relate that other person to what this first person did. That’s what’s really bad now a days. We want to paint race by what one person may do. That’s never right. Everybody does something wrong. That never affected me because like I said, I was only about three. When I went to grammar school, we had a wonderful lady. She would come in the restrooms when we all would get excused to go to the restrooms. She told us to call her Lulu. We all loved her. She’d come in the restroom, and she’d just give us hugs. We’d hug her. Everything was wonderful. There was nothing about whether she was a different color than us. In fact, she was the only hug I’d get all day long. We just loved her. Then one day she came in there and she told us that no longer can we call her Lulu she has to be known as Miss. Brown. And we could no longer hug her. That’s all she said. We were all thinking what happened? Nobody explained. Don’t know if another parent said “nuh-uh you’re not gonna hug my child.” I don’t know. All we knew was that there had to be a distance now, between us and what we knew as Lulu. JP: Yeah. DL: That was my two early things learning about race. Then when we went to school. They merged the schools together. We had Stephens-Lee that was the Black school. Oh, and about Lewis 2 Stephens-Lee they were the hit of the Christmas parade because their band was awesome. Everybody loved them. That’s why they went to the Christmas parade, just to see them. You know someone, nobody ever knew, did not like the way they did their band because they had some rhythm and could really strut out there. So, they couldn’t do that no more. Nobody knows who did it. Then we merged and there was no problem that I saw when we came together for the first time. No problems we all got along. We talked together in class just like any other school. It was not a problem until that race riot. That riot they had in ’69, wasn’t it? JP: Yeah, it was ’69. You didn’t see any frustration or anything leading up to what happened? DL: No. No because it was an instigated thing because they brought the bricks. Those were what I considered my friends out there throwing bricks. I remembered the day. I don’t know the beginning of it. That day I had a friend, and I rode with her. She had at that time a G.T.O. they called it goat. Kelly Green. We were gonna go ahead and just home and leave because we didn’t have to wait on me. She had her car. I remember going down the hall, we were together, and then there was the first fight. I knew the black guy. I knew him and he was always so nice. Him and this white guy were fighting. I didn’t know the white guy, so I didn’t know what he was. It didn’t look like he was on the defense. He looked more like he was on the offense, and I thought what is going on? Then we went outside to try and just go on and go to the car. Then this other student was coming down, he had been hit with a brick and he was bleeding. By the time we got to the school parking lot here’s parents trying to come in and get their kid and we were trying to get out. It was just very chaotic all of a sudden and with no warning. Everything was fine the day before. Then the next day though, she had too, my friend Kay had to go back to the school to pick up something in like a, they had a little preschool division where the students would teach or lead it and she had to pick up something there. There were all my friends, the black friends that we went to school. All of a sudden, it’s a different air. They said well Debbie, “How come you’re not in school today?” I said, “well because I’m just not in school.” I think they closed the school if I can remember. They were on the defensive. There was just a different air that was never there before with the friends. And these were all the black students that were there. They had gone to go, I think they got a little pay or something that day to work there. But everything changed. Now we all had some stupid ideas as far as race, but it wasn’t anything that would just be hateful. Then after the riots there was a divide. There was definitely a divide. I’m not saying with everybody but everybody that I saw, there was a divide. JP: The riots, it started with a student walkout, right? DL: Yeah, they walked. It was a planned walkout yeah. They had the bricks already there, waiting. I’m not saying that things shouldn’t have changed but there shouldn’t have been you know. Black girls on the cheer team, but of course there was always Black boys on the football team but there wasn’t the Black girls on the cheerleading team. Just more equality that way so it wasn’t always the white kids doing it. Although they felt like, well this is my school, and the B lack kids probably felt bad because they had to leave their school to come to this school. So, it was a time of adjustment as well. It was, just different after that. Which is like today there’s division. As far as, all the riots we saw taking place in the streets. You can’t help but just, that’s just not the way to do it. Lewis 3 JP: Do you think that maybe the African American students were frustrated with the closing of Stephens-Lee and the merging? DL: I’m sure they were. You know, because kids get so attached to their school. Yeah, I’m sure they were frustrated because this wasn’t their school. It was supposed to be their school, but it wasn’t their school. So it’s like, when I was a teenager I was involved with the band. I was a go-go dancer. [Both laugh] The music that we played we had a Black singer; we might’ve had two. But it was a mixed-race band. Well, you know, we never did win the band contest. Nope. It was the all-white that won. They had fancy costumes and their parents had money. That’s just the way it was. Although we were better. [Laughs] JP: Oh, I’m sure. [Laughs] Can you just take me, I know you’ve talked about it a little bit, but can you just take me through what that day was like for you? I know you were walking in the hall with your friend, but how did you feel? DL: Well, it was a shock, well you know that. It was kind of a shock to see your friends bleeding and fighting and your school all in disarray. We were going out the back way. Toward the front they said it was a lot worse going on. A lot of fighting going on. But you know we were just gonna get out of there. Of course, it was a good thing because I was talking to a friend of mine, and she didn’t go out as soon as we did. So, by the time she got to the school parking lot all the tires were slashed and they were beating up on some of the cars and everything. So, yeah. JP: What did the police do? DL: Well, I did see two policemen and they were helping the guy that had banged his head. I really didn’t see a lot from the police because they might’ve been more over on the front side of the school. JP: So, this event, did it change how you saw race after this event? Or race relations in general? DL: Like I said there was just a separation. There wasn’t any intermingling in the class anymore. There was just. It was like everybody had drawn separate sides. There was a line. Where before we talked and carried on. There was just a line. Okay y’all stay over there and we’ll be here, and everything will be fine. It’s just like, I guess I was more racist after that a little you know. To where before I wasn’t. I guess that’s probably a wrong word to use. It was just more, anytime you have a fight you kind of, it takes a while. There’s a bridge that nobody wants to cross over again. You know? JP: Yeah. DL: There’s something you have to work through, and you realize things are different. JP: Do you think that you were ever able to rebuild that bridge? That the school was able to rebuild that bridge? DL: I think they have. I don’t ever go to the ball games because I like to have a child there that I can root on. But I don’t know anybody there. Other than just my friends on Facebook that talk Lewis 4 about going to the football games. I think everything is resolved now. As far as I know there’s not any problems there. JP: What was it like for you to go to school before the schools were integrated? Was it any different when they started to integrate? DL: I didn’t find it to be any different. I just didn’t. Like before or after we had another school come with us. Of course, they changed the name and everything. It really didn’t bother me you know. I’m kind of a little bit more laid back than maybe somebody [Laughs] that really feels like they’ve gotta control. JP: Do you think there was parent backlash or teacher backlash at all? DL: I don’t think there was any teacher backlash. If there was parent backlash, I never heard of any. It just seemed like a smooth transition to me. But you know, I’m sure putting yourself into the Stephens-Lee students that that was a big deal. That was a big deal because they came there, and they didn’t feel like they had a voice in a lot of things. JP: Do you know anything about ASCORE or the Asheville Student Committee on Racial Equality? DL: Nope. JP: Have these events continued to affect your life today? DL: No. JP: No? DL: No. Uh-uh. [Laughs] No, uh-uh. Although I think some of them on that [Facebook] feed are still all into it. But nope. We’ve been in ministry for, we just retired our ministry. Our last ministry was in Fayetteville, North Carolina. And Fayetteville, North Carolina is probably the most racially mixed town in North Carolina. I was surprised when we went there how, at least the people in the first church we went to, I mean they were, they didn’t want anybody coming in there. So, when we were there, we started reaching out and bringing in different races. Did you know that some people didn’t like that? It was mainly the older people. Then we went on and we had a, we started a small church that was, I think we had six different races among sixty people. [Laughs] So, it was fun. Our church dinners very first, and it was like a foreign, everybody brought their foreign dishes in, and it was fun! But you know, some people just have a divide. JP: I mean, as a student for you to be so young, it must’ve been hard to understand what was going on? DL: Yeah. The Lulu. When Lulu, when she did that it kind of freaked us out because we didn’t have any kind of idea why. But like when I was telling my son he said, “Do you think one of the parents found out and said something?” And that could probably have been it. JP: Do you think you would have any reason why the students would walk out and there would be a riot? Lewis 5 DL: Well I think, I know it was instigated. But yet at the same time they were not really being represented unless you were a football player. You know because football is everything. But as far as, there were no girl cheerleaders and I’m sure there weren’t or very few on different on you know the little groups? What did they call them? Like there was the leadership of the school in different areas. I’m sure they didn’t feel like they had a voice. JP: You said it was instigated. How do you think it was instigated? DL: Well there were, like my husband, he’s older and he drove into the front. He saw what was being played. You know because there were people from the outside that were not students there that brought the bricks. He said they even walked around his Corvette. You don’t touch the Corvette. [Laughs] JP: [Laughs] DL: They went and walked around it. Being a little bit intimidating. That’s just, you know, the way it was. JP: Yeah. DL: And the students they just, that was going to be their voice. That was their way to get heard. JP: Do you think they were heard after that? DL: Oh yeah. Yeah, they were heard after that. People, I guess the leadership at the school realized we’ve got to bring them in. If they’re going to be a part of the students, they’ve got to be a part of everything. I think it gave them a voice. JP: Sort of speaking of the administration, what did they think about it? What did the principal Clarke Pennell, what did he think about it? DL: I have no idea. It never seemed like, that I remembered that it was addressed or, I’m sure maybe it was among the teachers and everything. As far as the students, nobody, I don’t remember anybody trying to explain or deal with it. JP: So, it was sort of like you went to school the next week and it was like, you could feel the tension, but nothing happened? DL: Yeah. Yeah. The tension was there but I don’t remember anything. JP: Interesting. DL: Yeah. JP: Do you think there was tension in the city after this? DL: That, I never felt any or realized there was any. I’m sure there was in the parents. The parents they all felt, nobody likes their kid to have their school disrupted. But yeah. JP: Were you afraid that it would happen again? Lewis 6 DL: No, uh-uh. No, uh-uh. It didn’t even enter my mind that it would ever happen again. JP: Is there anything in particular that you would like to tell me about that day? DL: About that day? JP: About that day yeah. DL: No, that’s basically that’s it. One day we were friends, and everybody got along and the next day it was [bloop noise] separate. But how it is now over there, I don’t know. I don’t know. But I know it’s all equal as far as you know. I was a good achiever in something they get upset, it’s not because of the race. JP: Is there maybe a story during that time you’d like to tell me about? I know you told me about Lulu and about when you were three, but is there anything else that stands out to you? DL: Oh, I’m trying to think. No. Everything was pretty good. I know one thing; I never knew I was a cracker. I never knew that. You know when I learned about that? [Laughs] JP: [Laughs] DL: Probably just fifteen years ago. When I was going east in a wick shop type thing and this guy was black and a man shopping. And the girl, the lady she wrote a thing, I don’t know they were having some kind of fuss. He finally said “I’ll just call you cracker. You want me to call you cracker?” I’m thinking, “Why does he want to call her a cracker?” I never heard of that. [Laughs] So I don’t. I never knew that there was any kind of you know. I know there was always the jokes and stuff but in our house there really wasn’t a lot going on. I wasn’t really taught to, I know my parents didn’t want me to date somebody of another race. As far as, that was the only thing. There wasn’t any hate speech in the house. JP: It sounds like your parents were really influential about how you felt. DL: Yeah. Yeah. Because it was just, not any kind of hateful stuff going on. Of course, my dad being the maintenance of the city schools he had a lot of different races working for him. He was fine. JP: Could you tell me more about your dad? What was it like for him to work for the city schools? DL: Well, he was just always, I remember one time he was gonna go work over, I forget the name of the school, I don’t even know if it’s there anymore in Asheville. Of course, Mother wanted to go shopping and he said, “Well I can take Debbie over there because they’re having these little summer things.” Well, this was a Black school, elementary school. That teacher there, I made a little clay bird, and she was there. I liked her first off. She was so nice. She had her daughter there and she was so nice. I mean they took me in and loved on me. I remember my cardinal beak broke and I was so disappointed. She loved on me, and she said, “Don’t you worry about that.” She said, “We’ll paint it and it’ll look just perfect.” Well, it still had its beak broke but she didn’t think “oh that’s a little white kid.” A little white kid, well I never was one of the privileged. She loved on me. And so, she could’ve changed my way of thinking about race, but Lewis 7 she didn’t, she loved on me. And we don’t have enough love right now, nowadays. Regardless of mistakes made, we still need to love each other. [Starts tearing up] JP: I agree. I agree. It’s kind of sad. [Laughs] Sorry, do you feel like you were able to love people after the riot happened? DL: Yes and no. There was a little bit of bitterness. There was bitterness but it didn’t last long. Like in Fayetteville I just felt like I had a calling to go strengthen people. I don’t recommend that to nobody because you’ve got to know what you’re doing, you’ve got to know how to do it. Whenever I felt like the Lord wanted me to go, I’d go and try to help street people. It was always a good thing. It was always a good thing, but I don’t recommend that. I don’t recommend it. JP: Did you lose any friends that day? DL: Hmm, no. Well except the black kids they weren’t as friendly. That was the way they were to everybody. There was a line drawn. It was, I don’t know, there was just a line drawn and it just takes a while to get over I guess for everybody when something like that happens. I think I had one, which is kind of neat, I think she was the one that would throw in the picture, she’s throwing the brick, and I can’t remember but she was always my friend. She was always a lot of fun. She’s passed away now. The thing is her nephew and my son have been best friends since they were in high school together. Ain’t that kind of funny how that worked out? That I knew his aunt, went to school with his aunt and now he knew my son. They’ve been friends forever. They’re forty-five now. So, yeah. JP: Small world. [Laughs] DL: Yeah. [Laughs] It’s just like all that’s been done recently. It’s gonna take a while to mind the bridges. If they can be brought back. I don’t have any, whoever, I just like everybody. JP: Yeah, you just like everyone? DL: Yeah, people might not like me, but I like everybody. [Laughs] JP: I like that. [Laughs] DL: There’s always some good in everybody. JP: I agree. DL: Of course, I’m a Christian. I know Jesus came into my life and he changed it and turned my whole world upside down. So, I just like everybody, and I hope that they can see the love of Jesus in me. JP: Well, I want to thank you for talking to me. DL: Yeah? JP: Yeah, I really appreciate it. Do you have anything else that you would like to share? Lewis 8 DL: Nope but I will say this, in high school they didn’t teach, well if they taught it I think they might’ve had a class just for the black students as far as black history. So, I wasn’t really taught anything. They just sort of touched on some things. But since I’m a history… I love history. JP: Yes! DL: Love it! Love it, it’s fascinating. Now I go on those, they’ve redone all they old videos, I go to sleep watching those things I just think they’re fascinating. But anyway, I read, I read about slavery. I read about all that went on. It’s really a different story in many ways then what people want to say nowadays. Yeah, nobody wants to be slave. There’s… have you read anything about the old slavery days in the books? JP: Yeah. DL: Yeah, it’s fascinating. One thing, like I said nobody wants to be a slave, nobody should be a slave. People don’t bring out this one thought. I don’t know if you’ve ever thought about it. But those women and those people, they forget America was the last one to really join in on that slave issue. They were trying to keep up economically with the rest of the world where they had to. I have stood at that port where they sent out [starts tearing up] slaves in Senegal. That’s an awesome place to stand. If you ever get there go to that port. It’s nothing but you’ve seen pictures of it, that hole where they walked out. [Crying] Anyway, these people who were slaves, sold by their own country into slavery and they were bought and brought here, they changed the world. By the position they were put in. They raised those rich kid’s kids to become leaders. They were the ones who took care of them. They took care and raised them up. Those people brought them prosperity. They did a lot in their suffering that nobody talks about. They took their suffering, and they did it and of course they fought through it. They raised a generation. They did it. So that’s an awesome thing to think about. What they really did in their trouble. Then they rose above their troubles. JP: It’s a powerful image. DL: Yeah. Um hm. JP: Thank you, for telling me your story. I appreciate it. DL: It’s fun because I like history. I wish you well with all you’re doing. JP: Thank you. DL: Opt an A. JP: Thank you. END OF INTERVIEW

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Debbie Lewis describes living in Asheville in the 1960s and 1970s. She shares her view on race relations during this period, the impact that school integration had on the community, and how the Asheville High School Riot of 1969 impacted her interpersonal relationships.

-