Western Carolina University (21)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- George Masa Collection (135)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2901)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (422)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6798)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (153)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1463)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (2008)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2924)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1941)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (195)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1672)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (556)

- Graham County (N.C.) (236)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (525)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3569)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4913)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (35)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (13)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (215)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (135)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (982)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2182)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (86)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (3)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (185)

- Envelopes (73)

- Exhibitions (events) (1)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (815)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (6090)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Notebooks (8)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (5)

- Portraits (4568)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (181)

- Publications (documents) (2443)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Relief Prints (26)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (1)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (18)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (462)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1482)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1923)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (190)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (111)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (2012)

- Dams (107)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1196)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (45)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (119)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (72)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

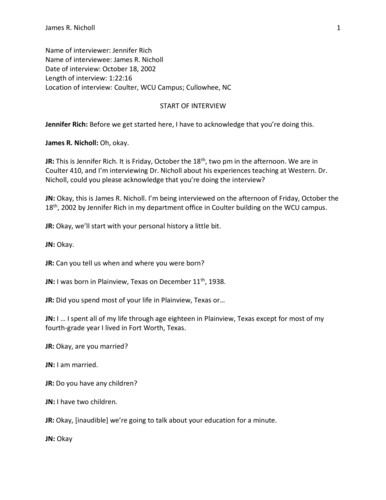

Interview with James R. Nicholl

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

James R. Nicholl 1 Name of interviewer: Jennifer Rich Name of interviewee: James R. Nicholl Date of interview: October 18, 2002 Length of interview: 1:22:16 Location of interview: Coulter, WCU Campus; Cullowhee, NC START OF INTERVIEW Jennifer Rich: Before we get started here, I have to acknowledge that you’re doing this. James R. Nicholl: Oh, okay. JR: This is Jennifer Rich. It is Friday, October the 18th, two pm in the afternoon. We are in Coulter 410, and I’m interviewing Dr. Nicholl about his experiences teaching at Western. Dr. Nicholl, could you please acknowledge that you’re doing the interview? JN: Okay, this is James R. Nicholl. I’m being interviewed on the afternoon of Friday, October the 18th, 2002 by Jennifer Rich in my department office in Coulter building on the WCU campus. JR: Okay, we’ll start with your personal history a little bit. JN: Okay. JR: Can you tell us when and where you were born? JN: I was born in Plainview, Texas on December 11th, 1938. JR: Did you spend most of your life in Plainview, Texas or… JN: I … I spent all of my life through age eighteen in Plainview, Texas except for most of my fourth-grade year I lived in Fort Worth, Texas. JR: Okay, are you married? JN: I am married. JR: Do you have any children? JN: I have two children. JR: Okay, [inaudible] we’re going to talk about your education for a minute. JN: Okay James R. Nicholl 2 JR: Where did you do your undergraduate work at? JN: I did my undergraduate bachelor’s degree at the University of Texas at Austin. I was there from 1957 until I graduated in 1961. JR: [inaudible] your master’s or your doctorate degree? JN: After three years of military service in the US Army, I returned to the University of Texas at Austin to begin graduate studies in English, and in 19 – that was in 1964 – I finished my doctorate in 1970 and did not pick up a master’s degree. They had a program there where you could bypass the master’s degree and go straight to the [inaudible] and I took that opportunity. JR: Okay, alright, what is your main area of specialty in English? JN: I wrote a dissertation on Shakespeare’s comedies and romances, [inaudible], plays, crosses the entire working career from the very earliest to the latest plays. I specialize in the development and the uses of irony; therefore, I was a Shakespeare expert by act of what I wrote my dissertation on. General area was moved to the English Renaissance. JR: Okay besides for teaching, what other positions have you held at the university? JN: From 1976 to 1980 I was director of freshman English, now called director of first year composition. That was an administrative position. Then from 1983 to 1990 I was head of the department of English at Western Carolina University. JR: M’kay do … did you teach anywhere besides Western? JN: I taught as a teaching assistant with responsibility for two courses per semester from 1964 through 1969 at the University of Texas [inaudible]. My last year I had a university fellowship, and I used that to complete my dissertation, and I didn’t have any teaching responsibilities [inaudible], but I also taught some summers [inaudible]. JR: And you came to Western in 1970? JN: I … when I… I finished my doctorate in June of 1970 and began teaching at Western Caroline in September of that year. At that time, we were on the quarter system and classes didn’t start until after labor day, so I began teaching in September of that year. JR: Alright, can we talk more about what got you into teaching and your research? Do you remember if anything inspired you to teach or is it just a necessary evil [inaudible]? JN: I… I didn’t… when I was an undergraduate I actually interviewed with the University of Texas as a premedical student [inaudible] to become a surgeon. I discovered that I was spending more time reading ahead and reading extra work in history and English courses and doing the James R. Nicholl 3 minimal amount in my science courses and figured out pretty fast where my interests lay. I had, at the time, an ambition to become a great and famous writer, someone like William Faulkner who was a very famous writer at the time … [inaudible]. That’s why I switched to an English major and my minor was history. It could’ve flipped either way because I liked both of them about the same, and as a graduate student, you had to have an outside field, and for me it was history. In any case, I went into the army because I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do. I had taken an aptitude test for the National Security Agency. I had done very well, got an interview, and the interview suggested to me that I needed to get some experience in the field of intelligence… [inaudible] that kind of thing. I took that advice, went into the army, for three years I was a counter intelligence agent. I worked out of Fort Bragg North Carolina, and later I worked in Germany. In fact, when I went back to graduate school, I was in the military reserves, and then another military intelligence [inaudible] during that time. While I was in Germany, I did take … my senior year I went to my advisor to be advised for the spring semester. My advisor was a very busy man, [inaudible] and he had not gave much attention to my work, and just kind of [inaudible] off on things. Since I was a graduating senior, he looked at my grades and for my junior year… well as soon as I switched my sophomore year, I essentially made As in everything except for foreign language, both in history and English courses [inaudible], and said you need to go to graduate school, which I hadn’t really thought about. We discovered though that I had missed the last date in the Fall, this was early December, to take the graduate record exam, and because I had missed that, I had missed the chance to apply for a fellowship or assistanceship at Texas for the next year, or for that matter to apply…apply to any place. But he encouraged me to take the GRE. I did in April the following year, and I did extremely well, and began to toy with the idea of going on to graduate school in English. Up until that point I don’t think I had ever considered being a college teacher. I very much wanted to go to Princeton University, walked over to my registrar’s office. They had a wall of graduate catalogues from all across the country. Pulled down the Princeton Catalogue, looked at the requirements to enter in English, and discovered that I needed two years of college Latin, which I did not have, and [inaudible] this was my senior year, I had a semester left, and I put the catalogue back and swallowed hard and went off. I did also take the GMAT [inaudible]… thought about law school, but I was in the army, doing the best [inaudible] work, and I had really enjoyed doing it. I had been in North Carolina; I liked being in North Carolina. I did not brag that I liked the rest of North Carolina [inaudible]. I drove through Asheville back in 1962 to take my car back to Texas before I went overseas to Germany … and drove through Asheville [inaudible]. Tunnel road was the main road … [inaudible] drove through the Appalachian Mountains. I-40 wasn’t there, it was very interesting, but I was intrigued by the area and stayed with a friend in Knoxville who was in graduate school in English at the University of Tennessee, and I think that was also [inaudible]. He was probably my best friend from high school. And I think that began to make me think a little bit about going into graduate school in English. When I was overseas though, I corresponded with a former roommate who was himself in graduate school, and he [inaudible] social work, not in English, and one of us must have raised the idea of me being a college teacher, and he was a very persuasive man, and he James R. Nicholl 4 outlined why he thought I would be a good college teacher. I took the bait, swallowed it, and began to try to get letters of reference from overseas. I very much at that point wanted to go to the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. Unfortunately, I hadn’t taken the advanced part of the GRE and they required that. I did apply to Duke. I got admitted but I didn’t get any financial aid, and my family couldn’t afford that – I’m the oldest of four children. I got admitted to the University of Iowa and my alma mater. I did go back to my alma mater. I could room… share an apartment with the fellow that talked me into going to graduate school. In retrospect I think it would have been smarter to have gone to one of the other schools, including the University of Iowa, and gotten a different perspective. But at the time the University of Texas was [inaudible]… made some administrative changes while I was there, really kind of slowed things down … [inaudible]. In any case, I ended up at Western Carolina University kind of by fate or accident. Um, I was applying to four-year liberal arts colleges. I wanted to be a teacher and not a researcher. My dissertation director was more of a teacher than a researcher. I certainly had classes with people who were heavy researchers and were very able in that regard. That did not appeal to me. I liked teaching from when I very first began to do it as a teaching assistant and was able to teach, I guess… maybe four or five different kinds of courses in five years. In any case, I was applying to those kinds of schools and had not – I had sent out a whole 50-60 applications. The job market was actually beginning to kind of dry up. The baby boomer burst was kind of over in the fall of 1969, and I was starting to look in [inaudible]. I wanted to come to North Carolina. It was the state my wife and I [inaudible]. We moved down from her home in [inaudible], driving down the Blue Ridge Parkway in Asheville, and stayed several days in Asheville. We went to the Biltmore Estate, and she’s one of those people that keeps a scrapbook I believe with the tickets that she pasted in with the admission price in 1967 was three dollars and fifty cents. So you can appreciate how inflation has really just taken off. We were able to eat – to have a nice dinner – at the Grove Park Inn, which today [laughs] I don’t think I can afford. It certainly was much more reasonable in those days. We then drove back through Chapel Hill and Duke and looked at Duke and Durham before we returned and then moved back to Texas… got a U-Haul back to Texas and finished grad school [inaudible]. But I had a … as I was starting to look for jobs, I had a good friend in graduate school that had [inaudible], was a Furman graduate, and had married in college. He was a big fisher – outdoors man – big fisher and hunter, and the MLA job list came out. The Modern Language Association does this – still does this. They put out job notices that schools have turned in about four times a year, and one comes out in October. Well in October this came out and there were about four or five jobs listed from Western Carolina University, who wanted a Shakespeare specialist. Of course, that piqued my interest, and I happened to run into [inaudible] and I said “[inaudible] what do you think about this… I don’t remember how to say the name… Western Carolina University at this place”, and he said “oh that’s really nice up there. My wife Stef and I used to go up there to fish and camp and stuff and you’d really like it.” And so I thought, “well, you know, what have I got to lose?” I was looking for a job in North Carolina. It was the place we’d like to be. We had literally sat down that fall – early that fall – my wife was working full time as a computer programmer and I was writing my dissertation, but we sat down one evening early in the fall, and she would type my dissertation as I finished parts of it. She … we sat down with a [inaudible] atlas and James R. Nicholl 5 began with I guess Alabama and worked on through all the alphabet [inaudible]. This was when there was a lot of racial problems and we just kind of wrote off Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and so forth, but North Carolina was a state we both liked. It was kind of between in-laws: my parents still were in Texas and hers in Maryland, and so we put like three stars by it and every place else kind one star. And we didn’t want to go to a big city and so forth. We didn’t want to go to Florida. I didn’t think we wanted to go to California… the west coast was kind of out. In any case I applied. I got an interview. Ironically at that same time I got an interview at Wake Forest University. I literally flew the same flight from Austin, Texas to Atlanta. There I switched to Piedmont Airlines and one time I went to Winston-Salem, and one time I went to Asheville, and I still remember this. It was a Delta flight into Atlanta, and they served steak back then even to the cheap seats. And I had the same steak dinner two weeks running. It was very predictable. The Wake Forest job it turned out was never filled, but I had interviews at… in Denver which [inaudible] was the department head at the time. He had come here from the University of Florida. [inaudible]. My first question to him when I walked in was “how do you pronounce the name of the place this college is located?” He said “ku-low-ee.” We had every… we did not call it… we, we hadn’t come up with Cullowhee. We had … we had about three or four variants of that, but not Cullowhee. And he explained. And then we went from there, and it was obvious that I was probably going to get an on-campus interview, which I did, and I got one at Wake Forest [inaudible]. I came here, uh just a little side [line]. When I came, the Forsyth building was just going up. This was in February of 1970. Forsyth building was under construction. The University Center was brand new. Uh, the bookstore was actually in the University Center. The campus was obviously going vibrant. I liked the people. We were in McKee, the top floor, the old McKee building when it was still just converted from an elementary school. [inaudible] these old wood floors and real high ceilings. It was not the nicest building I’d ever seen, but English departments aren’t often in the nicest building [inaudible]. As it turns out we are, I think, in the nicest building… classroom on campus [inaudible]. But anyway, when we were leaving, when they were going to take me back to Asheville to the plane, and they were actually literally working on four-laning uh the road between Boston and probably about [inaudible] North Carolina. Interstate 40 was not completed through there. Um, we left in uh … pretty early… I think we had a quick lunch and [inaudible] were senior professors in the department, were going with me to the airport and we got down to where [inaudible]. That was the only red light I think in all of maybe in Jackson county, certainly in Sylva, was right there. We got … as we were approaching that light, I said “couldn’t we go down into downtown Sylva and just look around?” Which we had not had a chance to do. We looked at Forest Hills as a possible place to live [and buy a house] and he said “oh no no no, we’re running kind of late. We don’t want you to be late for your plane.” So I didn’t think a thing about it. We got on over there … we got over there about an hour early. We drank two or three cups of coffee, and finally my plane came, and I departed, and I said goodbye to him. It was pretty obvious to me that I was going to get the job offer, but I later figured out that they didn’t want me to see Sylva. At the time [the paper plant] was in full operation. Scott’s Creek was black from the production process. There was a huge smoky chimney there, and the machinery James R. Nicholl 6 was very loud, and there was the [A & P] grocery store was right across the street from there at the time where Family Dollar is now, and you could drive over there to buy groceries and park a clean car and come and get in your car and you could literally write your name in the ash and air pollution, but you could come close. [laughs] and so they didn’t want me to see this nasty little [side of town]. That was … wasn’t much of a town in the 1970s. But my wife and I got reconciled to it. It was kind of ironic. We talked about it. She was from Baltimore and I’d spent time in [inaudible] Germany and in ten years in Austin which was not as large as it is now, but it’s a good-sized town [inaudible]. And we said “well, you know, we’ll just go to Asheville every week, and we’ll go to Atlanta about every month or two, and we’ll be okay.” And then we moved here, had a couple kiddos and so forth, and there was a Sears catalogue store that we used a lot, and we did drive over to Waynesville to buy groceries. There was a wonderful Bi-Lo over there [and some other shops and I’d go there to get beer]. But anyway, as it turned out, I’ve been here now since 1970. It’ll be 32 years. I don’t think I’ve been to Atlanta – actually visited Atlanta rather than just driving through – I think I’ve been there 10 times, and we’d go to Asheville maybe 3 or 4 times a year. And so we made an accommodation to the way things were in Jackson county [inaudible], [and we’re very pleased. It’s been a wonderful ...] [cries] [inaudible] JR: Do you want me to stop [recording?] JN: No, I’m going to be alright. But I come from the [most family]. I really feel blessed to have had the job I have and to live where other people come to vacation, and I’ve lived here year-round [inaudible]. And I’ve had wonderful students, yourself included, and it’s a really great college. We’ve had some bad times here at the university, and bad things have happened to students and faculty members and neighbors and things, but on balance… I’ve sometimes thought about “well what if I had gotten an offer from Wake Forest” and what would have happened there and how different my life would have been, but I’m pretty sure that from my personality [became the things I like to do] and I just … this was the place for me. We were able to find… land was still comparatively cheap, and we were able to find a little 12-acre piece of land that had a 5 acre hayfield meadow pasture in it [my wife was a horse lover and I had become one], so we could have horses and a nice home, and our kids lived… grew up in a certain environment with good schools [and had super neighbors]. It’s been really … it’s been special. I wish everyone had the opportunity … I do think that the university had drawn in some [directions] and academia has gone in directions that make it a less pleasant environment to work in than it was in most of my working career. [And I was actually emailing] probably my favorite graduate student just a few weeks ago, and his life has now … gotten a doctorate and he teaches English education at a college in rural Kentucky and I said “I believe I was a faculty member during back when we looked on this kind of [inaudible] and the types of responsibilities we have and … and the kinds of things that we can do [I think those have changed] [inaudible]… is that I have had time for things like this interview. If I was a pure researcher even at Wake Forest, but particularly at some of the schools that I deliberately didn’t apply to. For the Chapel Hills and Dukes, if I were there, I would have had … when you came to see me, I would have said “Jennifer, I’m sorry, I’m too busy. I’m trying James R. Nicholl 7 to finish a book; I’m trying to get an article; I’ve got to go somewhere this weekend to give a presentation [inaudible] and I don’t have time to do this.” And … and I would have been sorry, but I would have also been pressured by [the position and the research.] They’re not … They’re certainly higher than they were when I got here or even… they literally changed as I got here. When I was hired, I was told by [inaudible] if you write two or three … if you go to [inaudible] in Atlanta and give two or three presentations, you’ll be tenured, and that will be no problem. You finished your doctorate, so you’re just going to be promoted and etcetera. JR: I hate to interrupt you, but I’ve got to flip the tape. JN: Oh okay [laughter]. Then ironically, I got tenure very quickly in the wake of what was called [inaudible]. That was a very troubling time, about 1973 and 4. The chancellor at the time, Alexander Pow, he was a real I guess go getter type. [inaudible] University of Alabama [inaudible] their [vice president of graduate affairs] came here with big plans, and then I think it was 1972, he had a terrible stroke, I think at a football game or something … he had a stroke and was [inaudible]. Then they had an acting President. Jack Carlton came in and not … he had kind of come up too fast, and tried to do too much too fast, and one of the things I learned as administrative department head is don’t try to change things too fast because it scares the hell out of people. And it scared this faculty. He put a freeze on tenure for instance. Well, for instance I think in English alone I think 5 or 6 faculty members came in on tenure track [and I came in in 1970], so we were all working toward tenure, and then he said, “well there’s not going to be tenure for a while.” This upset the tenured faculty and they started a petition to get him removed, and they were tenured, and they signed it openly. But I still remember going downstairs to the history department, and one of the leaders was a man named [inaudible]. He had been [a dean] here, and nobody was going to push him around. [already they had people] they had a bunch of people in history there [inaudible], and so those of us who were on tenure were kind of escorted down there by [for instance our] department head, so we could sign this secret petition that was kept in his desk drawer [probably] locked and was not going to be shown to the administrators and the board of trustees and the board of governors, the president of the whole University of North Carolina systems [inaudible], but they were going to be able to say, you know, all of these tenured professors signed, and then we have another list signed by x number of untenured faculty members who are upset with President Carlton’s manner of operating. And then the most amazing thing happens. This almost never happens. This is … if you know the history, this is like when the English rose up and took Charles I and chopped his head off. Well, the king got killed. He didn’t get really killed, but he got promoted. All of a sudden, he was needed at the general administrative of the University of North Carolina systems in Chapel Hill and was taken there. And an acting chancellor came in, a fine man, I’m trying to remember his name [inaudible]. He was from Charlotte and we really wanted him to be the next president for chancellor [laughs]. But Carlton went and he … I’m not sure what happened to him, but it was a very difficult time. However, when this new man came in from Charlotte, and I think that was maybe … by James R. Nicholl 8 that time it was the spring of ’74 [inaudible] all of a sudden, they tenured a bunch of us. So normally you wait, and you go up to tenure in your sixth year. We got it in the fourth year without doing any paperwork or anything. It just kind of … it was like being dubbed a knight or something without ever having been in battle. It was amazing. But then, this is [inaudible], but then when it came time to be promoted to associate professor, which normally goes with tenure, that didn’t come, and Dr. Robinson came in. Well he has a new way of operating and he was going to raise the standards of service and scholarship in that university, and he expected more from the faculty. And so, the first time that I and several others of my colleagues went up for promotion, we didn’t get it. We got real upset and began to work hard and got promoted the next year, and I got promoted to [inaudible] and was a full professor in 1982, which 12 years is just about as fast as anybody [inaudible]. But there were lots of people that got promoted in the early 70s who had never published anything etcetera. Ultimately my colleague [inaudible] and I did a series of textbooks for freshman English that were published by national publishers [inaudible] and that was how we got our scholarly reputation. Although I published about … oh about 15 articles [inaudible] chapters in books [inaudible] and some other scholarly things [inaudible]. I have not done much with Shakespeare. Not nearly as much as I wish I had. My articles often had been on teaching and how to teach better. I [inaudible] to that in the arts and sciences college [inaudible] teaching award. I and professor [inaudible], he’s a wonderful chemistry teacher, actually tied for the award in part because the committee had 6 members on it and they reached a vote obviously split, and so we shared the award and both got it, and then … actually, each of us served on that committee. That was in 1994. We recommended when we got on the committee, we said “you better make this a seven-person committee, or a five-person committee so you don’t…so you always have a winner [inaudible]. But I was very pleased to have had recognition. I had not really begun to work that hard on my teaching until … after I stepped down as department head in [1990], I had gotten real frustrated with the department because I couldn’t … I was always being interrupted by the administrative team and couldn’t be the teacher I knew I wanted to be. And I really developed in the 1990s as a teacher I thought. I’m not sure what my students would say, but [inaudible]. But I discovered that it was important to do something to cause a student to for sure read the assignment before they came to the class, and I needed something other than just giving them a quiz. I had done that [even when] I was a graduate student. I had tried to kind of use that technique and that was just time consuming [inaudible]. But anyway its… I’ve had lots of administrative kind of committee duties [inaudible]. One of the things that I was involved with, which probably deserves its own history, was the mountain area writing project. It was a summer cooperative project between Western and the University of North Carolina Asheville. It began in 1982. I did not … I was not involved that year because in April I actually had been riding a horse and it ran away with me, and I rolled off of it and was badly hurt, and I spent I think it was 11 days in the hospital recuperating. I did not finish the semester. It was early April. [It was the first Sunday of April out here]. And [Ben Ward] that used to founded or helped get going the writing center here, and then later the Faculty Center for Teaching [inaudible]. He was the representative, and then the next year I took over for him and did it I think for 6 or 7 years with two different people [inaudible]. And it still runs. At the time it was grant funded by the state. It no longer is that, but James R. Nicholl 9 that week we had 25 K-12 teachers from public schools in western North Carolina, I think it’s called district 8, and we’d go in for about 4 weeks in summer school and try to turn them into better teachers of writing. This is an [out goal] for the national writing project [from] Berkley, the University of California Berkley, and became a national movement and really dramatically I think changed the way writing was taught. Not only kindergarten through 12th grade but at all levels. [inaudible] teachers when I began writing … began teaching writing simply the way they were taught. They taught the book, and they weren’t really thoughtful. There was no research being done about how to teach writing, what works and what doesn’t etcetera. It was all kind of hit or miss [and not very] scientific. And there were … of course you had [good] writing teachers back then. I had some, and there were bad writing teachers too. [I’m sure] the same hold true right now. But that’s one thing I have always been pretty good at is teaching students how to write better. I had literally taught [inaudible] writing project through the time that I taught Methods of Teaching English in High School during the 70s there are probably in western North Carolina 2 or 3 hundred teachers in the public schools that have somehow been directly influenced by my presence, and I think that’s an important accomplishment that I’m proud of. [inaudible] [laughter] I’ve been flattered when students have stolen me [fit sheet]. They ask me usually, but when they borrow it I guess it’s a nicer way, or appropriated my [fit sheet] approach or something like that or to [keep one] to use in class [inaudible]. In fact, I gave a presentation last week … a faculty presentation about teaching techniques. I continue even though I’m in [inaudible] time and I [inaudible] in 1999 and retired from the state. I had bought retirement time because of my army service [since I had] 32 years in. The system had been here 29 years at the time, and then I went into a 5-year contract where I teach full time in the fall and do not have teaching duties the rest of the year, and I’m in the fourth year of that. I’m enjoying my teaching very much. I’m probably not looking forward to retirement as much as a lot of people would be. I’ll be 64 in December and 65 in that last year of teaching, and then I’ll [be cleaning this office out]and be glad for what I’ve done. I’ve really enjoyed it. It’s a … it’s a pleasure. I never have really liked grading papers, but I’ve learned how to do it different ways that make it easier for myself and less traumatic for my students. I guess you yourself are a victim of me. You’ve not only had Shakespeare, but you’ve had composition with me, so you’ve had … so you know that I’m pretty serious about you getting better and by and large I’ve been successful. You don’t… you don’t save every student. There’s no way. And I’ve got some this semester that I’m not going to be able to save, but if they’ll stay with me, by and large they’ll be better for the experience, and some of them will be much better. I mean [you can always be better]. If fact, there’s some good students in the Shakespeare class that are beginning to already be on their fourth play. They’ll be able to read Shakespeare so well that I’m getting suspicious that they’re going out on the internet and getting their [inaudible] answers. I haven’t been able to determine where you would go to get that, but … JR: I’m glad you brought up the internet. I was going to ask you over the years I’ve noticed that [the internet] has changed your job James R. Nicholl 10 JN: Oh gosh, yeah. Oh yeah. In fact, in … around ’79 or ’80 we got some major, major grants. I mean I don’t know if they were [a million dollars’ worth] but I think they might have been. That allowed some of us [inaudible]. And my wife was a computer person from … from the earliest days. Literally from when they used punch cards to [get the data] in the computer. I got some release time to take some computer classes. I got to go to an international media [inaudible] of something called … it was called [inaudible]. It was computer assisted instruction, or something like that. It was an association devoted to that. I remember there was … going to a program done by a man from [Belgium], but it was astounding to go there. I never will forget that this is 1982. This is before I had my accident. This is like February or something. And there were [some others down there with us]. Robby Pitman from the School of Education and Psychology was down there. He taught computer things down there, and he teaches computers [inaudible]. I remember going to the exhibits and there was a little company that had a big exhibit [inaudible], and never had heard of him. Nobody had much. And it was amazing to watch them become a major player, particularly in educational computing. It was very interesting to go and see different presentations there of how already they were using computers to train medical students to do better diagnoses. It was intriguing to have a man stand up and say “you know, there are 25,000 undiscovered uses for the computer, and that number will never get smaller. It will never shrink.” And of course, this is before something like the internet. The internet I didn’t know anything about. I didn’t know it exists. But the world wide web was really … when that came out I … I did continued to be interested … have had computers since about 1982. The first computer I had was a Radio Shack TRS [Model…model] 2 or something like that. I think it had 16k of memory. It had virtually no memory. It had the ol’… big ol’ … it had no hard drive, and it had the big 4 or 5 and a quarter inch [inaudible]. In fact, when I saw [the smaller sketch that looks familiar now] I thought “that doesn’t make any sense [inaudible]. You can’t get enough stuff on that,” not realizing that [inaudible]. In the 90s I was able twice, with support from the university to go … what was it called … at the University of Virginia has a computer center – an academic computer center – that’s doing fantastic [things]. I went once to learn how to use the internet and another time to learn how to [put up] digital images of letters and other manuscripts … primary material, and actually do one. I did a letter of a woman named [Lydia Maria Child]. I did the annotation for a letter in their archives there, and I could still go there, and we could go and look at it. But I think the second time [inaudible]… I think in ’93 but for sure in ’96 … I think in ’96 though was when they really had there the world wide web up and running, and we worked with some. And I still remember sitting there in the terminal and going to the National Museum of Australia online to look at a dinosaur exhibit, and I thought, “wow, this is going to change stuff.” There was a lady there in the group was using … she lived in New York City in Brooklyn … and she was a subscriber to something called America Online, which is now what we call AOL. And it was like “what is that?” And of course, we didn’t know, or we would’ve bought the stock [inaudible]. Anyway, who would have known? I didn’t have the foresight, but I’ve always been involved, and when you walked in today of course I was at my computer. This is about the … this is certainly the 2nd or 3rd Mac I’ve had. [I’ve been a big] Mac person … was not at first. I guess I had … first I had a regular [inaudible]. It had something called [WordStar]. It just took up James R. Nicholl 11 the length of the computer on the… I guess we got… I can’t remember, but I think we’ve had three or four, but the last two have certainly been Macintosh. And, you know, the email today for instance [inaudible] she was unable to preview it to make it an attachment [and get it to come over]. And we were both frustrated because that wasn’t very normal. She had tried like three or four times and couldn’t get it to come over and so forth. So we really have gotten very dependent on our computers, and count on them to help us keep in touch with our students, and my student if they are ill or have some problem [inaudible], and we have voicemail now. Literally in the old McKee building when I started teaching if you got a [inaudible] phone call, a student worker or the secretary came down to your office and you went down to the office to the … there were two phones – the department head had one and the secretary one at her desk – and then after a while we got one put in a little closet in McKee so that … they had a speaker system and they could call you to the phone. And the same thing in fact happened when we moved to this nice new building. There were speakers … [I don’t think you could see them], but they were … maybe they were in the hall, and they would ask you to go to this work room [inaudible] there was a work room right down here, and there was the phone, three lines on it or something [inaudible], and the same thing on each of the floors. You could be paged or something, but more often they simply put a note in your mailbox saying, “please call so-and-so at your convenience.” And so we didn’t have nearly the communication [inaudible] in retrospect. For instance, the voice mail I think we’ve only had [a couple years]. We got the phones finally in the office and we had [for a while] probably throughout the ‘90s you began to be able … for a long time we didn’t have direct lines, so we didn’t have direct, so the calls for the English department – it was wild on snow days, students calling, you know, “is Dr. Nicholl having class?”, “well let’s see. [inaudible] Yes he’s here,” you know that kind of stuff. And now they can call directly, and I [for a number of years now have began to] [inaudible]. But, okay, I’m getting talked out. You’ll have to ask me another question. JR: [laughs] You answered a lot of them actually! JN: Oh, okay [laughter] JR: [so we’re looking pretty good.] I want to talk a little bit more about the identity of Western and how it’s changed over the years. JN: Okay. JR: Would you say actually that Western has an identity? JN: You know, it’s so hard to judge something from the inside. JR: Yeah. JN: When I first came here, one of its identities was as a suitcase school. What that meant was that at every Friday, this is about … this is about 3 o’clock on Friday, and at the time this was James R. Nicholl 12 before the four lane was built through what’s called Catamount. I guess that was built in the late 70s and maybe early 80s, I can’t recall. All the traffic went down here by Wachovia bank. [There’s a…a post office was there.] You turned left where the sign is down there by [inaudible]. Went by Plymouth, the Bird building, which was then the administration building, and went down by where Hardees used to be, where Papa’s Pizza To-Go is now, and you turn left and you got on Old [inaudible], and there was a huge back up of traffic. If you can even imagine the traffic jam, and there had to be an officer posted there from about noon till about 3 or 4 to keep the traffic moving through the area. [And the campus kept being] unless there was a home football game, there would be… there might be 500 students on campus on the weekend, but that would be a high number. There would be kids that lived way off or something like that. And so that has changed. There has been a deliberate attempt to have more activities at the UC and other ways. And I think … there’s still I think far too many students go home on the weekends for all kinds of reasons. I think a lot of our students still are the first members of their families to go to college, and so there not [inaudible] that kind of. We have some very sophisticated students, but we also have a lot that want to go home a lot, or have to work, or want to work, and they have jobs at home, so they go home, and of course they have their family and friends there that they want to see. But that part of the school I wish could change. I think the academic [climate] would be a little more different if students were here, you know, 7 days a week. It’s changing enough so that the library used to not be open on Saturdays, for instance. Part of our identity has [inaudible] the kind of school that is pretty much [inaudible]. And that really … when our enrollment peaked before in the late … about ’77 or so, and when I came here Dr. [inaudible] showed me where the English building was going to be, which is kind of up above where they’re building this second rear edition on the University Center, up on that bank. [inaudible] was where the English building was going to be. But of course, we didn’t end up being there, but that’s another story. But at the time they thought the school was going to go to 10,000 students pretty soon, and Scott was a brand-new dorm, and Harrill was built just a year or two after they built these high rises. And then they figured out these are not a good idea. [inaudible]. But I like the size of the school. But we did not know … and it let in some students that were not very good, and [inaudible] when they were doing this he said, “[tell you what, they’re not going to stay [inaudible].” Bad students drive out good, and then they drive out one another. And so it was only when the honors program began to be developed that we began to really attract at least some cream of the crop. And then that has grown and grown, and that has [lifted] a whole kind of academic tone of the school so that it wasn’t the kind of place where I used to always ask my student, I don’t remember asking your class, I think [inaudible] I’m not sure why, used to ask students the first day or two of class as they introduced themselves, they would pair up and that kind of… JR: Okay you can pick up from where you left off. JN: Okay, well I was talking about Dr. Bardo and his influence on athletics, but I think that’s a piece of our profile that’s kind of missed. Well [western schools] sometimes have pretty competitive teams, and real good baseball for instance, really good track – terrific track and James R. Nicholl 13 baseball. But big-time winners, but not anything else. And I know the year [inaudible] came that we won the Southern Conference, and got the double A tournament in basketball, really a highlight of sports here at WCU. In some ways more than when we went to the championship game in football. [inaudible]. But I remember also that [Keith Jarrett], he was a sports writer still at the Asheville paper, wrote … he’s a [play man] and he wrote a satirical column. We beat Davidson, and he started this column after we beat them with a bit from an old commercial, “please pass the jelly,” [with this kind of country hick at a sophisticated table] and he really put down Western you know, and said, you know, well the combined WCU SAT score is one half what the verbal or math is at Davidson, and that kind of thing. You know, you get 7 or 800, you can go to Western. So, and I walked in my Shakespeare class, and they were upset, and I was upset, and we were so frustrated, and we talked about it. And [I think you know from the tape] I’m emotional, and I was crying almost in frustration, [inaudible] [cries]. Because they had had something for a minute, and then this guy comes, this [smart Alec guy], and thumps them you know on the head, and bumps them back down from their position of “yes we did something.” I mean it’s like a little kid coming in with something he or she had made at school, and then a parent not even wanting to look at it, or something you know. And there were WCU alumni that pulled that advertisement from the Asheville Citizen Times. They caught hell over there for a year because of that. And I still remember several years ago when we [beat] Appalachian here in football, and I was down ushering at the time. And here’s this crowd on the field, and they eventually tore the goal post down and they took one set up to the chancellor’s house [laughs] [he still doesn’t know] how in the world they got it up there [inaudible]. They put it up in his yard like a trophy, you know. But [laughs] [Jarrett] was out there, and I was right there. They took a picture. I used to have it on my door of … what’s his name … [inaudible] that plays for the Carolina Panthers. He started for the panthers. He had been a huge star from that year. 41. His brother plays for … [Joey] plays for Appalachian. Anyway, they took a picture. He had the mountain jug on his shoulder. He’s up on some guys shoulders. They take the picture. This is on the front page of the Asheville paper, I think. Certainly the sports page. Well [Jarrett] is out there. [Keith Jarret] is out there, and I’m a pretty big guy, you know that, and [Jarrett’s] not a little guy, but he was there taking notes, and I went over to him, and I looked him in the eye, and I said, “you better get this one right.” [laughter]. Because I was so mad from back there and the way my students were hurt because they had lived in the shadow of Chapel Hill and Duke and State and Appalachian, and then they come out of the shadow, and then the cloud comes back over them, you know. And that’s kind of been … we’re kind of almost like a hard luck institute. You know we’re the [poor mountain relatives] we’re the relative that our students if you look at their SAT scores and so forth. We and Pembroke, of the white schools against the traditionally black institutions in the NC system other…if there weren’t those traditionally black institutions to be below us in [inaudible], we’d be at the very bottom. But we’ve had wonderful [alumni support]. We’ve had [inaudible], and we’ve had some wonderful faculty. I can assure that when I came here … I mean I came from a big-time school… walked over and looked at the library and the library has always been a really great asset to the university. I knew what to look for, and I was confident that I could do whatever research I James R. Nicholl 14 wanted to do in Shakespeare … was going to be able to do it there. I was quite confident, and I’m still a library liaison. Have been for about the last 7, 8, 9 years. And particularly once we began this [consortium] [van between] Asheville and Boone and Cullowhee, the ABC system. We have a terrific library facility. And our internet access is so great that somebody that can’t do their stuff here really kind of has a problem. I do remember though, as department head, when I first became department head, I [inaudible], Duke and Chapel Hill were hosting a department head workshop for MLA, and they had their department heads there and speakers from all over the country, and going into the Chapel Hill library and going down, and they have open stacks – it’s an old fashioned library. It’s not nearly as nice as ours. Anyways, and going down there, and they had so much stuff that I thought, “my goodness, how could you not [publish] with all of this here.” Because they really had more than we did. We had enough, but they had… it was almost like too much. It was like in your face. You can’t use it as an excuse there, like “I couldn’t find a book,” because, you know, you could. But in any case, I’m still circling around your image question. I don’t like what has just happened, which is [inaudible]. I like that [mountain bug joy]. It came in under Dr. Coulter. I think they paid [inaudible] 10,000 [and up] [inaudible]. Maybe we’re still using it, but I’ve heard that we’re going away from this. It has [inaudible], and I think we probably have it capitalized. On our … our location. I don’t think I have any of it. [inaudible] well this may be a piece of it. When Dr. Robinson came in, we had a fancy kind of logo with the seal or something, but Dr. [Wade] was a Chapel Hill graduate now. I think he always secretly wanted to be a Duke graduate. And some of those big schools would have a logo. It says “Harvard” or “Duke,” and so he bought … he got some stationery made for the English department and in little tiny letters it would say “Western Carolina University.” Very plain block letters. “Department of English, Cullowhee,” blah blah blah. He sent a piece of correspondence over to Dr. Robinson, who was trying to…who knew image was important … who kept the campus…the campus was beautiful around 1985. You couldn’t have found a prettier college campus anywhere, and a cleaner and neater one. If it wasn’t clean, Dr. Robinson was driving around…there was a … if there was a candy wrapper or something out, the grounds people caught hell, and they had to go there right then and there and clean it up. But anyway, Dr. [Wade] sent something over to President … or Chancellor Robinson, and it has this little ol’ bitty black type [inaudible], but he was just like, “what are you doing?” And he didn’t understand either even though he [inaudible]. But Dr. [Wade pushed it] … he actually made it smaller than what Duke was. It was all kind of modest. It was kind of like a satirical thing. You know you can satirize two ways: you can make something too little or too big. You can make the hamburger the size of a jelly bean, or you can make it the size of a pizza pan. Well he had gone for the jelly bean [laughs], and it just was kind of silly. But we’ve always kind of [inaudible] for an image. We used to run some ads and things like in the Charlotte paper. I think we got a much more aggressive bunch of people recruiting students. I’m always kind of amazed by the kinds of students we get, and where they’re from, and the diversity of them [inaudible]. And we have a lot of talented students. I mean I have an honors class right now of 12 students, and I [inaudible]. I said, “I keep forgetting that you are freshmen.” They’re in a 200-level class, and there are 2 of them in there that are not freshman, but the rest are freshman. I said, “you act like you are juniors or seniors.” I mean you tell them James R. Nicholl 15 one time, you give them the assignment, and then they just do it, and they make As and A minuses on everything. In a regular class you tell them, and then you tell them again, and then you underline the instructions, and then they still screw it up. And maybe that’s just college. I do know that when I came here, and I could go back and look at it, but I think this is all across the country, there has been [grade] inflation, and I know that pretty fast I figured out that the assignments I was giving to students at the University of Texas, and admittedly those were top students. Those were the kind of students you get at Carolina. Only maybe a third to a fourth of my students here would have been really able to cope with those kinds of essay topics and things like that. And maybe I’m short selling, but I think that I’m accurate in realizing that the students were not as academically able and sophisticated too. They hadn’t had as good of training. They often came from [inaudible] kind of schools that you know just weren’t as good. And the ones that came from the big schools were not the best students. You know if they came from Myers Park and Charlotte or something, they weren’t the top students. The top students were at Davidson and Duke and Chapel Hill. [inaudible]. But on the other hand, our students don’t have… they know who they are and what they can do, and they’re not afraid to work. And I still remember getting a letter when I was department head. A young woman went on a writing … she was getting a writing concentration and went on an internship in a [inaudible] company in Arlington, Virginia, south of [Washington, D.C.]. We got this glowing report back from her, and in essence it said this. Her name was [for instance Jennifer, which is your name, and her name might have been also, but let’s just say that it was Jennifer for the purposes of illustration]. We get this letter from her supervisor, she’d worked there that summer, and I think it was a paid thing also. It may not have been, but I think it was [inaudible]. And she said Jennifer is the one who would change her own typewriter, [that was when we still had those], [inaudible] etcetera. We had these girls who had gone to [inaudible] and [inaudible] these fancy [inaudible], kind of like ivy league schools, and you know, well I’d go to [Columbia] and I’d hurt my nails if I changed the typewriter. I’d get ink on my hands, you know. Well Jennifer, “well I’ll do it, here.” And so, this kind of I can do it attitude, and I will do it, and I don’t have to have servants, has been an important part probably of the success of our alumni and some of them have been extremely successful. Many of them though have just been good citizens. I think we’ve trained a lot of good citizens. We’ve certainly tried to. But the quality of the faculty, the quality of the people that I was hired with was extremely high, and I think in the English department and many other departments on campus have continued to hire top quality people. It’s just a shame that in the last 7 years the budget situation in North Carolina has made it so that some of our best young faculty have begun to look for other jobs and find them and take them. We lost a PhD from the University of Illinois to a school in Louisiana. [inaudible]. When I came out, you didn’t even want to go to Louisiana. You know, well he got about a four or five thousand dollar raise, his wife had a better working circumstance, and so forth. And you just hate to see that happened. You fit in well here and [you do everything with our English as a Second Language program], and you hate when you get something up and going and about to succeed and then budgetary or other constraints make it fall short. And I think one of the things we need more of [at this university is more…] we need more aggressive grants seeking by everybody to get that non-appropriated money. It is not James R. Nicholl 16 state money. We need to get more support from our Alumni, to the degree that [we have it]. Now, so many of our alumni for many years were going out to be teachers [inaudible] until very recently, and [then maybe both of them are teachers…] [inaudible]. We weren’t making enough doctors and lawyers and [inaudible] the kinds of business men and women that end up being vice presidents and CEOs and so forth. One of the things that strikes me [inaudible] talking about that is how women have really come forth. When I first came here, the leaders were [printed to be me] and I know that when I was department head, we used to have an all awards night for all the academic awards, and I had to wait till the Es and present the English award, so I had to wait after business gave its, and I noticed by the late 80s that almost all of the award winners were women from the school of business. These kinds of guys [that were going to be in business you know] [inaudible]. I had the secretary do it for me. They were getting nowhere, and it was women who worked like this “Jennifer” I talked about that weren’t too proud to get their hands dirty. They weren’t too proud to study. You know, they weren’t going to go party and so forth. They were going to… and I know for instance one of my best students I ever had was a girl from [inaudible]. She is working her way up, has a family and everything, but is working her way up [inaudible] is a fortune, probably 100 … the company has its own woman CEO, and [Cindy], you’re not going to find a whole on her, and her sister for a long time has taught at Pisgah over in Canton. Sent both of her kids over here to the honors program, and its amazing. The current chairman of our board of trustees, [Joe Cocker], was my student in freshman English, back in that old McKee building. He is now a senior vice president I guess at Bank of America and made a wonderful life for himself. He was a tennis player, an African-American … one of the early African-Americans to come in here. When I … when we got … when I got in in 1970, I had a student worker [inaudible], I don’t know what happened to her. The student worker assigned to me and Dr. Nancy Joyner, we shared a joint office, was in the first bunch that came in. She graduated either in ’71 or ’72, so she had come in in like ’67. That’s when this place integrated. And so, Joe was like ’75 or ’76. He was a tennis player which, not a football player you know, not the stereotypical stuff. But boy he was a good student. He worked hard. In my class, [but that was the way he did it in my class], I was demanding… I tried to be fair always, and you’re a better judgement to how fair I was, and I would work with somebody, but boy he wouldn’t work, you were in the wrong place. If you weren’t going to do the work and come to class, you’re in the wrong place. I would say most Western students are that kind of student that are going to do that. They’re going to develop their skills. They’re going to use their energies [inaudible]. And they’re going to succeed. I wish I could answer the [inaudible] question, and I wish then I was better. I wish I was … had taught at a place that as a school I could be more proud of. Ironically though, I liked the place… when I was at the University of Texas, it was 35,000 students, and last night a student called me [inaudible]. This school is now at 52,000 students. Well this is about as many people as [inaudible] Asheville, North Carolina. Just university students. That doesn’t count staff, faculty, etcetera. So that school was way too big, and I thought, “gosh the size of school.” This was the size of school or a little bit smaller. I mean I would’ve been at Davidson or Lenoir Rhyne or places like that. That’s kind of where I was applying, you know like Wofford. A school of 2, 3, 4, 5 thousand. And so, for years I didn’t even put a WCU sticker on my car because I didn’t want James R. Nicholl 17 to drive up to Baltimore and see my in-laws and recruit some more students for Western cause I liked the size. And I don’t think getting big is the real answer. I think quality [inaudible]. If the honors program was to 5,000 students and we had 5,000 students here, so be it. On the other hand, we have an obligation to this region to take students who aren’t necessarily honors students and help them realize their dreams it seems to me. That’s what I’ve always tried to do I think, and I’m much more conscious of it now. I have a person like you who has a dream to maybe be a college librarian or something like that, and whatever I can do to help Jennifer get there is kind of what I want to do. Now she has to do her part, but if she wants to do her research project in an area that I think will help her accomplish this, I’m going to work with her. I’m not going to say, “oh no you can’t do that.” Because she ought to be able to say, “now, Mr. Nicholl, it’s my dream. It’s my degree. It’s my goals. Please let me go there. Help me go there.” They haven’t had to say that to me very much. I’ve … I’ve always asked, “what are your future plans and goals?” so I can say, let’s see if I can help you be better so that if you’re going to be a lawyer, or if you’re going to be a manager, or you’re going to be a nurse, or you’re going to be whatever it is, you’ll be a good one, and you’ll be proud to be [inaudible], and we’ll be proud of you. And then if that happens, they’re going to be grateful for the place that helped shape them [inaudible]. You know we probably have about 30,000 alumni now, which is an astounding number, and in many ways, it may be larger than that. That’s a lot of folks that have been touched by this place. And when I say alumni, I mean graduates, not just people who have gone here for one semester. That number is probably [given our poor attention]. That number is probably about 50 or 60 thousand. I don’t know. It could be larger than that. But a lot of people had good experiences in the English department. [They come back, and I hear from them out of the blue]. You know I just had [a student from Tennessee, a graduate student] [inaudible]. Her name was Jennifer too, there’s lots of them. JR: Popular name. JN: Well [inaudible]. But anyway, question? JR: Talk a little bit more about student life and how you’ve seen it change over the years. JN: There were always fraternities and sororities here. I still remember a boy in my first Shakespeare class that I taught the first semester I was here. I think that he was a Lambda Chi Alpha. He was also director of the student paper. He was a real outstanding leader, and we’ve had some [inaudible]. He went on and got a PhD in journalism. He’s on the faculty at Virginia Tech, you know, a major school. I mean a big one. A real honest to goodness major school. And so, we’ve had that kind of outstanding type all along. Not as many as I would have liked. The fraternity and sorority system had probably mostly been good. I don’t know that they drank as much back then as they seem to have gotten to doing. There began to be more drugs around I think in the mid to late 70s. Kind of a subculture of drug use I’m sure exists to this moment. I know that our students got busted back in the spring, so that’s probably stayed fairly stable. James R. Nicholl 18 The thing we’ve never had here is school spirit. I came from a school that had school spirit, but I think that when you’re winning in your athletic program more than any other thing because again, that’s how people… one way… the easy way to judge a place [inaudible] is their football team. And that’s what we do in small towns throughout the south. If my football team could beat the football team from your town, then my town is better because our boys are better. And if our girls can beat you, that’s that much to the better. [inaudible] girls’ basketball [inaudible]. Well when you’re the one that’s getting beat up on, you don’t have much of an image, and I’ve always had students I’ve really liked. I’ve had really, really good smart students. Always [inaudible] amazingly smart and talented. We’ve always had real hard-working ones, and I’ve always had some that just … I’m not going to say. They wouldn’t do the work. The sad ones are when they do have talent. The others that don’t have talent and work as hard as they can and still kind of can’t do it, that’s the ones I feel sorry for. I really feel that they didn’t get a fair [shake] maybe back further in their… in their training in public schools or wherever it was. Or maybe they come from … a lot of our students come an increasingly so from… from family backgrounds that aren’t totally stable. Single parent situations and things like that. The high schools of course aren’t that great a place anymore [inaudible]. I don’t know, but I think … I think students, and of course I have for the last 6, 7, 8 years always had an honors class. Almost especially in the fall. So, I’ve had a lot of contact with honors students, and they’ve always been kind of top notch. [inaudible]. But I’m not sure the students … I don’t see too much … that girl’s name was [inaudible]. She put the [grades] in my gradebook. I could dig out my grade book from back then and show you … if I said, you know, “Nancy was really good,” you could look, and you could pick out which name she wrote in my gradebook. You would know. You would say, “is this Nancy’s,” and I would say, “yep, that’s her.” [and I think she was in business]. I still remember giving her a hug at graduation. JR: I have to switch the tape. JN: Oh okay.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Jennifer Rich interviews James R. Nicholls on October 10, 2002. James Nicholl was born in 1938 and raised in Texas. Dr. Nicholl ended up in Western North Carolina perhaps by fate. He started teaching English at WCU in the early ‘70s after receiving his graduate degree and continued teaching at WCU for over thirty years leading up to his retirement. Here he depicts the evolution of WCU and recounts his times as a professor at the university.

-