Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (24)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1388)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (1794)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2393)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1887)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (161)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1664)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (233)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (478)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3522)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4692)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (25)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (12)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (211)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (981)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2113)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (247)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (68)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (184)

- Envelopes (73)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (811)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (619)

- Maps (documents) (159)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (5835)

- Newsletters (1285)

- Newspapers (2)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (12975)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (6)

- Portraits (1663)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (151)

- Publications (documents) (2237)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (1)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (15)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Vitreographs (129)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (282)

- Cataloochee History Project (65)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1407)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1744)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (167)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (110)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (1830)

- Dams (103)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (917)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (154)

- Hunting (38)

- Landscape photography (10)

- Logging (103)

- Maps (84)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (71)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (245)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

Interview with William (Buster) and Genella Gray

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

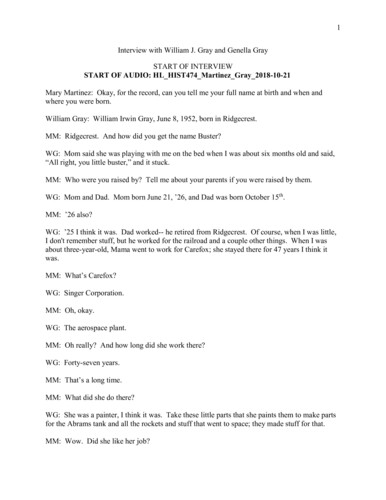

1 Interview with William J. Gray and Genella Gray START OF INTERVIEW START OF AUDIO: HL_HIST474_Martinez_Gray_2018-10-21 Mary Martinez: Okay, for the record, can you tell me your full name at birth and when and where you were born. William Gray: William Irwin Gray, June 8, 1952, born in Ridgecrest. MM: Ridgecrest. And how did you get the name Buster? WG: Mom said she was playing with me on the bed when I was about six months old and said, “All right, you little buster,” and it stuck. MM: Who were you raised by? Tell me about your parents if you were raised by them. WG: Mom and Dad. Mom born June 21, ’26, and Dad was born October 15th. MM: ’26 also? WG: ’25 I think it was. Dad worked-- he retired from Ridgecrest. Of course, when I was little, I don't remember stuff, but he worked for the railroad and a couple other things. When I was about three-year-old, Mama went to work for Carefox; she stayed there for 47 years I think it was. MM: What’s Carefox? WG: Singer Corporation. MM: Oh, okay. WG: The aerospace plant. MM: Oh really? And how long did she work there? WG: Forty-seven years. MM: That’s a long time. MM: What did she do there? WG: She was a painter, I think it was. Take these little parts that she paints them to make parts for the Abrams tank and all the rockets and stuff that went to space; they made stuff for that. MM: Wow. Did she like her job?2 WG: Oh yes, yes. She seemed to. She enjoyed [it for forty-seven years]. MM: Forty-seven years. Wow. And how about your dad? Did he enjoy working for the railroad, do you think? WG: Well now, he worked for the railroad before I remember; I was too little to remember that, but I just remember him working at Ridgecrest Baptist Assembly, and he retired from there, took a medical retirement from there; he got emphysema, so— MM: What did he do there? WG: Maintenance. MM: And did he like it? WG: Yeah, he worked on plumbing, drove a dozer, various things he done. MM: And how many years did he work there? WG: Don't know. MM: Many years? WG: He was there a bunch of years; I don't remember how many it was. MM: Uh huh. And do you have brothers and sisters? WG: Two brothers. MM: Younger or older? WG: Older. I’m the baby. MM: You’re the baby? WG: I’m the accident. MM: Were you much younger than them? WG: About four years. MM: Four years? And were you treated like the baby? Did your mama favor you? WG: No, she favored the middle brother. MM: Really? Nobody ever favors the middle kid.3 WG: Yeah. Skeeter, my oldest brother, was Dad’s favorite. (2:46:7), Jimmy was Mom’s favorite— MM: And who’s favorite were you? WG: I was the accident. MM: Did you know your grandparents? WG: Yes. MM: Tell me about them. WG: My granddaddy and my grandmother—my original, biological grandmother passed away way back when my mom and dad was little. They are from Macon County, and he married Granny and they moved out here when Mom, I mean Dad, and my aunt and uncle were little punks, little kids. They moved out here to Ridgecrest, and then that's where we've been ever since. My great-grandmother was a full-blooded Cherokee Indian. MM: Really? WG: And then on my mom’s side, I never did know her parents. I knew my grandfather, her dad for a little while, but I was a little kid when he died so I don't remember him too well. MM: Are you in touch with that side of the family at all? WG: No. MM: Did you have other family close by besides your grandparents? WG: I had my uncle. My aunt lived in Franklin, so those were the closest relatives I know of that I ever had any contact with. My uncle built this house where the Dribbles are. MM: Oh really, no kidding, wow. Would you describe yourself as a close family? WG: Not really. MM: Not really. Are you closest to any-- What member of the family are you the closest to? If any at all. WG: (Silence) MM: Sorry.4 WG: We’re not in real close contact. I mean, we’re not feuding or anything, just not the type that we get together often. MM: Yeah. What was the house like that you grew up in? WG: Exactly like the Dribble’s house. Dad and Tom Clyde built that and then they built my dad's house when I was about two years old on the valley called Gray Rock Valley up there. MM: So it was a two-bedroom, one bath? WG: Three-bedroom, one bath, living room, kitchen. And we had a porch on the outside and of course he enclosed and made that the dining room. MM: Oh okay, okay. And what kind of chores-- I'm kind of exploring the work that people did as part of the Smithsonian exhibit, so I'm looking to see what people did as a child, doing chores, and first jobs, and then later jobs, and how that affected their ideas of work. So what can you tell me any chores that you and your brothers— WG: When we first come up, we didn't have a ranch, but we had a cow, a milk cow; we had to milk the cows. We had some hogs that we butchered every year. We took care of the hogs. Had a plot of ground that we were responsible for hoeing and all that, and plowing. And when I was a real little pup, so my grandfather lived below us, and we build our house up here on about four acres or five acres or whatever it was. My grandad, I never knew what he worked at before he retired, but always know him he was out there in the garden doing something with the plow horse. And I remember the first tractor we got was a steel wheel; it had steel spikes on it. You had to crank it, two-cylinder, that thing whup you too boy. MM: How old were you when you had to work the tractor do you think? WG: Usually my older brothers did because they was-- I was a little wormy thing growing up, so I guess about 10 or 11 is when I got big enough where I could handle it a little bit. MM: And how old were you when you first started doing chores like milking the cow, and helping with the hogs and garden? Do you remember? WG: Oh, probably about six or seven. MM: Six or seven? And how did you feel about doing that work? WG: It was just one of those things; it had to be done. MM: It was just part of life. WG: Had to be done. It was delegated out. And then when I got into school, we wasn't doing so much garden work or anything, but my job to come home as housework.5 MM: Oh really? And what did you have to do? WG: I had to clean the kitchen up, clean the house and stuff like that. MM: ‘Cause your mother was working. WG: Yes, she was working. She was working shifts, night shifts at the time, and Dad was working day shift, and my brothers they were doing other chores, so that left me to do— MM: So do you do housework today? WG: I do. MM: You do? So it kind of continued? I mean you ended up being a really neat person maybe, or? WG: I’m OCD. MM: Oh, are you? Good thing you don’t come to my house. Wish I had a little of that in my house. So you keep things very clean and that kind of started when you are young, and it just continued? WG: And she’s (indicating his wife Genella) just like me. We worked out fine on that one. MM: Tell me about your first paying job? WG: Worked at Camp Crest Ridge when I was 14 years old, for girls. My job was to carry those stinking steamer trunks up on the hill. A lot of them weighed more than I did. MM: So this was a summer camp for girls. Christian summer camp? WG: Yep. MM: And they brought big steamer trunks for the summer? WG: Big. They was big old trunks. MM: No kidding. WG: I knowed that they was a pain to haul up that hill. MM: Well did you get over being scrawny by then? Did you have to do it by yourself? WG: I actually didn't get over scrawniness ‘till I got drafted in the military. When we got married, I weighed 135 pounds and she weighed 98 pounds.6 MM: Oh my goodness, wow. Okay, so your first job was at the summer camp hauling those— WG: And then I worked during summer at Ridgecrest too. After that, my next job I worked the summer I worked with my dad in maintenance and stuff at Ridgecrest. Then when I graduated from high school, I went to work at Pine Valley in Old Fort; we were dating then. MM: What is Pine Valley? WG: It’s a furniture—makes Ethan Allen furniture. We were dating so when we got married, she worked at Bekin's second shift, so I quit there and went to Beacon, work and there I got a whole raise to a $1.90 an hour. MM: How did you guys meet? WG: High school. I will not say what I said when I first seen her, but I still remember what she had on. She had on a lavender shirt, purple skirt. Me and the buddies setting against the wall. That’s the only redhead I’d-- MM: Really? WG: So it took about six months to get a date with her. MM: She was hard to get. WG: She was. And I’d asked her out for prom. I remember I’m going to take her out before to get to know her. If that had been our first date, it’d been our last one. MM: Why? What happened? WG: I’s stupid. But I’d already asked her out for prom; that was my word, you know. So we went how to prom and had a good time, and we went on from there. MM: She loosened up a little, huh? WG: (Genella laughs). Yeah. Not a whole lot. (Laughter). So we got married July 3, ’71. I got my draft notice in December of ’71, so I joined, like an idiot, the Army because I wanted to be a police. I joined the Army military police instead of getting drafted, come to find out I could've got the same thing. I went to the (ap? 11:07) station. I went to Fort Jackson for basic. While I’m in basic training, passed that no more draftees will be sent overseas, only volunteers. I said (11:18) crap. MM: Because you wanted to go overseas? WG: No, no more draftees would be sent over. That's the reason I volunteered, so I could get what I wanted.7 MM: Oh, okay. WG: And maybe avoid Vietnam. But if I waited and got drafted, I would have avoided Vietnam and had a year less service. MM: Who knew, right? WG: Right. So they cancelled the war on me and then I stayed at Fort Bragg for two and a half years, so I didn't even get to get out of state when I was in the military. MM: Did you enjoy your work? Were you with the military police there? WG: It was okay. MM: Not that great? WG: Yeah. It’d been a whole lot better if I've used my head instead of being a dummy. I'd like to go back and change a few things that would've made the military a lot more fun. MM: Yeah, but you were young. WG: Young and dumb. MM: Why did you want to go into police work in the first place? WG: I don’t know; just like police work. The respect; people had respect for police officers. MM: And did you kind of feel that from when you were a kid or-- do you remember the first time you thought, “Gee, I’d like to do police work?” WG: I never really thought about it. When I was a kid, I didn't think about doing anything really. MM: But you just kind of gravitated towards that and when you decided to sign up you thought that would be the way to go? WG: See, I wanted to be on the Highway Patrol or the state troopers. MM: So then what happened when after you got out of the military? How long were you in the military? WG: Three years. I got out in July, ’75. Went to work at Beacon's Manufacturing for a little while, back to work ‘cause that's where I was working before I went in the military. Went to work for UNCA campus police in ’76 or ’75 or something like that. I was working shifts, four shifts, and they was anywhere from 4:00 to 8:00 in the morning. Never day shift. And Wendy 8 was little, still in diapers and I said, “Nah, I want to see my young’un every once in a while.” So I quit doing that. Done several other jobs. MM: Like what? WG: I went to work for, we went back to Pine Valley; I drove a truck for National Welders, delivering oxygen and acetylene. Worked at Beacon’s. There for a while I was working at beacons from seven in the morning until three in the evenings, and then I go to (13:48) from 3:30 in the evenings to midnight. MM: Why did you work so much? WG: ‘Cause I was in debt. MM: To support your family? WG: Yeah. MM: That’s a lot of work. WG: She worked at Beacon. We had a lady that was taking care of Wendy; she was a big influence, a good influence on the young’un too. Then I moved to Florida like an idiot. MM: But you didn’t like Florida? Why? WG: Her brother talked me into coming down there to seek my fame and fortune. So we went down there, and I went to work for a steel fabrication plant down there. Gosh, the phosphate mines went to hell in a handbag, so I got laid off. I was out of work for a while. I went to work for Tampa Oxygen and Welding, called me back to steel fabrication; I went back, and got laid off again. Then I worked for (14:43) aluminum extrusion plant down there until my dad passed away, and we come home for the funeral and I told us we’re not going to be down there in that situation again and come back home. So we came back home— MM: That was in what year? WG: ’84. What did I do when I come back? I think I went back to work at Pine Valley at the time. Then I worked for (15:12) Propane. Worked there for 12 years. I got up to service manager or whatever. Job come open with state, so I got back into police work. So then I retired from the Highway Patrol. Now I work part-time for the Black Mountain Police. MM: Did you enjoy working for the state police? WG: Yes. MM: Liked it?9 WG: Yeah. MM: What did you like about it? WG: I don't know, just a job. Of course, I was in the federal section of it where I done all the hazardous material and stuff like that. If there was a big truck with hazmat on it, I’d go do it. It was just interesting; I liked it. MM: Why did you retire? WG: Seven years ago from the Highway Patrol. MM: And why? WG: Age. MM: Age, they made you retire? WG: See, you can’t work past 62. MM: Oh, okay, because it’s law enforcement, right? WG: And with the state, you can’t work past 62. I retired at 58, and then I went to work at O’Reilly’s for a little while, and now I went to work at Black Mountain part-time. MM: How did you feel about retiring? WG: Scary. MM: Yeah. And are you happy working with the Black Mountain Police Department? WG: (Nods yes.) MM: So you kind of got to continue what you always wanted to do. WG: Right now, I've got one of the best police jobs you can have. MM: Why? WG: I work 15 hours a week. I go through primary school and see all my kids; I go to the elementary schools and sell all my kids and say hi. I go help them on calls if need be; I'll let them tussle or whatever, but if there's paperwork or somebody needs to ride the county’s (16:55), the full-time guys take care of that; I don't have to do that. MM: That’s great.10 WG: So, I've got it made. MM: That’s great. Do you have a philosophy of work, do you think? WG: Yeah, if you’re going to--- I told one time, If you work for a man and he pays you a dollar an hour, you better make him a dollar and a half an hour ‘cause if you don’t, he don’t need you.” You do a good job. Don’t do something unless you do it to the best of your ability, no matter what it is. MM: And where do you think that came from? When did you feel like you adopted that philosophy or work? Did you always have it, or do you think you got to that as you got older, or? WG: I’ve always been a hard worker; lazy hard worker. (MM laughs) MM: Do you have kids other than Wendy? No? What did you tell her about work? Genella? How would you like to be interviewed after Buster? I think that would be great. GG: I could join in. WG: ‘Cause she was a big influence on Wendy ‘cause I was—She was the one that did a lot of influencing for her. I was the disciplinarian. MM: Okay, we’ll talk about that in a minute, but Genella, could you then tell me the name you were born with and when and where you were born. Genella Gray: I was born in Mission Hospital in Asheville. My full name is Patricia Genella Lewis. MM: And they called you Genella? Why did they call you Genella? GG: I was named actually after, I don't know if you know Carl Ricker, who owned a lot of Asheville actually now. But his mother’s name was Genella, spelled G-E-N-E-L-L-A which is different. Most people want to spell it with a J. G-nella is I guess what it is. I was named after her. That’s her name, Genella Ricker. My mom and dad went to church with her at the time I was born. MM: Okay, we'll go back to your history in a minute, but let's talk about Wendy right now. So, how did you raise her with regards to work and chores and that kind of thing? GG: Well, she was always raised up to have to do chores. When I would leave for work, when she was old enough, I'd leave her a list of stuff to do like put the dishes in the dishwasher, or wash the dishes, or make your bed. Didn't always work. I think what she would do was I would get home around 4:30 and about 2:30 she would start. MM: Make sure it gets done before mom gets home. 11 GG: Yeah, yeah, so mainly before Daddy got home because she wasn't afraid of me. But she's never had a lot of what you call, I guess, chore chores other than those few little things like washing the dishes or making her bed or something like that. But she actually started a pay job fairly early. She was like 15 and she worked up here, they call it the “Blue Cone,” the little ice cream place. That was her first job when she was 15, and she worked there until she got old enough and she went to work at Ingles. WG: After school she wanted a car, and I said, “No, I’ll not buy you a car. If you want one, you have to work and pay for it.” I said, “I’ll help you with the insurance, but you buy your own stuff.” So she did. GG: And she had very good (20:37). She had a very good work ethic. MM: Has she always had a very good work ethic? GG: She does; she really does. She'll go when she is not able and stuff like that. MM: That’s wonderful. Do you think most people have that today or do you see a difference in the kids? GG: Not anymore. WG: I see a difference in the kids, especially-- I go to the schools. I see stuff going on in schools now that would have taken my skin off the walls if Daddy had come down to the school for those things. I just can’t believe it. One kid the police is having to deal with in primary and elementary school, and Mom come down, and “If you’ll be good, I’ll take you for some ice cream.” She’s rewarding his behavior, instead of if my mom or dad had to come to school. He’d a busted my hind end all over that place in front of everybody. MM: So you were raised with pretty strict rules of disciplinary? WG: I was raised up, “Yes, sir; no, sir; yes, ma’am, no ma’am,” stuff like that. Polite, manners. We wasn’t the bestest of kids; I got in trouble, Jesus Christ, did I get in trouble. I earned every whipping I got. Should have got some more that I didn’t get. Wendy did too. She got frailed a few times coming up. MM: But she turned out really well. WG: Yeah, she used to be bad to pitch fits. And one day I was going to AB Tech, taking a psychology class at night. So every time go to bed, she just pitches fits. All there crying, carrying on a tantrum, and it was kind of hard for me to do, but done that one night and she started beating a wall with her favorite doll. So I got up, ‘cause I was mad, thank God I caught myself ‘cause I started to grab her. So I grabbed that doll and said, “You want to tear up something?” And I broke that doll in a million pieces. And she only had one. We was poor, and 12 she only had one little box of toys. I locked her toys up for two weeks. She never pitched another fit. I don't know if she's seen in my eyes that I've crossed a line, or what— MM: But she never pitched another fit, wow. WG: But that scared me worse than it did her, I think, ‘cause if I’d a got a hold of her— MM: Oh, I remember those times being really mad at my kids. So, do you feel like you, Genella, have the same-- Did you handle discipline the same way? Or? GG: I don't remember my mom or dad ever spanking me, ‘cause I was precious. (Laughter). But now, my mother would get after my brother, I remember her taken the broom and chasing him, and stuff like that. But I can't ever recall getting a spanking. But I don't know, I had this fear, I don't know if it was fear or respect or what it was of my mama, my daddy too, but my mom was the one that put the fear of God in you, so I guess I was just too afraid to misbehave. MM: Did they give you work and chores when you were little? GG: Oh yeah, my mama was a true believer in kids doing their—I was the oldest of my six brothers and sisters. I say that, but my daddy had been married before, and my mom have been married before and they each had two children by those marriages, and then they got married and I was the oldest of the six that mama and daddy had then. So I did a lot of babysitting the younger ones all my life, pretty much raising them, that's why I had the one child once we got married because I raised six of them. But I remember Mama, I had to do a lot of cooking, a lot of housework, but we also, even being girls, she made us get out and help with the mowing of the yard, and there was no such thing as “you get paid for that.” That was just your responsibility to do it; you didn't get any allowance or any of that kind of stuff. MM: What did your parents do? GG: Mama worked at Beacon Manufacturing. She’d worked before that, I can’t remember where it was, but what I can remember she worked at Beacon Manufacturing. She retired as a supervisor down there on the cutting floor, where they cut and bagged all the blankets. And my dad, during the war he worked at the Naval—he wasn't in the military, but he got the Naval Station up in Maryland; he worked up there. And then, what I remember as a little girl him working was called Boling Chair Company, Georgia Pacific now, in Azalea. They made furniture and like that and then when he retired, he retired from an asphalt company out in Enka-Candler. He worked there as a night watchman in his later years, then he passed away of lung cancer when he was sixty-four. MM: Oh, young. GG: Yeah. MM: What was your house like?13 GG: It was just a typical house, three bedroom, one bath. MM: Kind of like Buster’s? GG: Yes. We all had to, there was a room with just the girls and a room with the boys because there was two bedrooms and lots of kids, nobody ever got their own bed, nobody ever got their own bedroom. Then we did move when I was a teenager to down here Swain City and, but still had to share a bedroom with one of my sisters. MM: And how old were you when you started having to do chores? Do you remember? GG: Oh my gosh, all my life—little, six, seven? Somewhere in there. MM: And how did you feel about work, chores? You didn’t think about it one way or the other? GG: That was just—Everybody did their work, and that was just the— MM: And what was your first paying job? GG: My first paying job? Well, I babysat. I would do some babysitting for the neighbors and stuff like that, and I did get paid for that. But my actual my first paying paying job out in public was Beacon Manufacturing. MM: And how old were you? GG: I must have been 18, because you had to be 18 to work there. And it was night shift; it was a little office where you counted how many blankets got cut and that type thing. MM: A lot of people around here work there. GG: Um hm. WG: That was the biggest employer. They started, they built that plant in 1923 or somewhere like that. It was a big employer for the valley here for many years. MM: And when did they finally close it? Do you remember? WG: It was in the seventies or eighties. Must have been the eighties. GG: Must have been. MM: Put a lot of people out of work. GG: It had to have been because I went back to work there for a little while after your dad died. After we come back from Florida, I worked there for just a little while, and then that’s when I got the opportunity to go work for the town of Black Mountain and worked there 30 years.14 MM: You worked for the town of Black Mountain 30 years? Wow, Genella, that’s amazing. GG: I retired from there in 2013. MM: Did you like it there? GG: I did. I always enjoyed my job. I started out in the water department, then I got transferred to accounts payable and payroll. Then when I retired, I retired as the HR coordinator. MM: And you enjoyed it. And how did you feel about retirement? GG: I liked retirement. I still like retirement. I went back, for about two years I went back part-time but I recently quit, and I don't do anything now. MM: But that makes you happy? GG: It does. Well mainly I take care of my granddaughter and do stuff for my family and things like that. MM: So did you work full time throughout your married life? GG: I did. Well, except for three years while Buster was in the military. He didn't want me to work and down in Fayetteville we have the one vehicle, and Wendy was little. WG: I was in Fayettenam, so I didn't want her working. MM: You were in Vietnam? WG: Fayetteville. We always called it Fayettenam because it was just a little Vietnam down there; it was a bad place. GG: Every week just about you heard about somebody getting murdered or— WG: I was the military police and one time I was driving for the Provost Marshal, a colonel, and I got to talking to a girl that worked at headquarters. Come into work one day and she was gone. She had contracted somebody to kill her husband and put him out to the drop zones. So, dang. So, I didn't want her, of course – I was a bit of a hellion when I was in the military too. I liked to indulge in too much adult beverage every once in a while. We lived in a 10 x 40 trailer, and that was her world, and I never thought because I was always working or doing something, and that was where she stayed at. Every once in a while, we go off to Rose’s or someplace ’cause we didn't have a lot of money so there wasn't much we could go out and do. But if I had been married to me in my military years, I have left my sorry self. MM: So what was it like for you during those three years?15 GG: It was very boring sitting in there with a baby. I was close enough to my parents, but we didn’t get, we couldn't afford to come home but maybe once a month where they get to see me and my brothers and sisters and all that, so it was a hard time. MM: So it sounds like you both enjoyed your jobs; you enjoyed working. GG: Yes. MM: So you had a family and you had the work also. How about Wendy? Does she work? GG: She does; she’s a nurse. WG: And then my son-in-law, he’s a state trooper. He’s now a sergeant with the highway patrol. So he followed in my footsteps. (Laughter). MM: Genella, do you have a philosophy of work? GG: Well I don't know that I've ever had a philosophy of work. MM: Well, how do you feel? When you go to work, what do you think? GG: Pretty much like Buster. You know, I just do the best job I can do. I always try to get along with people. Sometimes that's hard, when you're out working with the public and stuff, but I attempted to treat people the way I wanted to be treated. MM: Do you notice a difference with the work ethic with people younger? GG: It’s different definitely. We’ve got people with what I saw with the town, you earn so much sick time, and that sick time would go toward your retirement if you had it. The kids coming along this day and time, they get five hours of sick time, there going to burn five hours of sick time whether they're sick or not, they're going to use that time. They don't think about it as anything that I should be there, I have responsibility for that job. It's more like what does that job owe me versus what can I do. WG: And that's one of the bad attitudes I've noticed, it's not, I love my job, I love the people I work for, I'm dedicated to them, people I work with, do what I can help you out, and vice versa you help me out. It's now what can I screw you out of. And it is bad. You got on my bad side, I'm going to tell on you. Too much childish garbage going on anymore. There's no work ethic. MM: How’s Wendy raising her daughter with regards to work? Can you see it? WG: I don't see the chores like we used to do. Of course, it's not our place— MM: Yes, it’s not your place, exactly.16 WG: I would like to—If she does something-- she’s a good young’un, God bless ‘em, I'm thankful for that, if she does something, it’s “You clean your room up, we’re going to give you a dollar.” “No, it’s your room, you clean it up and I aint’ giving you nothing.” GG: If it’s really bad, I’ll say, “Let’s do this,” and it’s, “What am I going to get paid Mamaw?” “Well, you’re not going to get paid nothing.” WG: That’s one thing that I was always, we were taught coming up, you will clean your room; you will do your chores. The consequences of your not doing your stuff is you got your ass busted. If you do stuff, good job, goes the next thing. If it wasn't a good job, usually you didn't want to come home and didn’t get your hind end busted, so I’m good to go. (Laughter). MM: So you knew when you’d done a good job ‘cause you didn't get beat. WG: My family was never was one so much to praise the good stuff. And that's the way I am, regrettably with Wendy. When she’d screw up, I’d chastise that but when she done something good, I’d say, “That’s what you’re supposed to do.” I try to do it now, “Good girl.” I try to praise the good stuff, and also chastise the bad stuff. But not as bad as I did with Wendy. She's mine, but her mama and daddy needs to raise her. MM: It's a different era now. GG: It is. MM: I did not raise my kids with-- thankfully they have a really good work ethic, but it wasn't because of anything that I did. Unfortunately, I don't know why, they were working so hard at school, I didn't think they should have to – I coddled them, and I really regret it now, especially now as I sit and listen to you about how you were raised, and how you raise your daughter. I wish I done that more. You know you wish you could go back and do things different in the military; I wish I could kind of go back and do things a little differently with parenting. WG: 20/20 hindsight is always there. But I know that discipline as far—I didn't know this until Wendy got married, but she (referring to Genella) threatened me with her all the time, “You wait until your daddy comes home.” MM: You didn’t have to discipline, you just threatened her with Daddy. Well, this was great. I really appreciate this. 17 WG: My car payment’s a $124. a month, and utilities –and I think I was bringing home about $300 a month. GG: So no grocery money. WG: So single guys that was in the barracks, they was going to go to town and partake, and they let me hold their meal ticket. We had a full-order kitchen and a short-order kitchen. So I’d go to the short-order kitchen and get a hoagie and that was our supper. MM: Wow. GG: That was something, and I think back now, and I say, “Gosh, I’m so blessed now.” MM: Yeah, well you came through hard times and look what a lovely life you have now. GG: You talking about that, it was hard times that made us stronger, whereas there's kids nowdays, they think… GG: They’ve never had to sell blood to buy milk to feed your young kid. I had a box of tools I take to the pawn shop every month, they give me $10 for that box of tools, and I’d get paid and I go get that box of tools back. I had to sell my 19 – loved that car, a 1971 Mach 1 Mustang, same one in “Diamonds are Forever.” Every time I see that movie, tears come to my eyes. But I had to sell my car, ‘cause that's $124, that’s half my paycheck every month. So, I had to sell it, and we just drove beaters and stuff. MM: How long were you poor do you think? WG: All my life. MM: Really? WG: My mom, she also said I had champagne taste on a beer budget. I always liked the finer stuff. So, if you want something nice, you gotta work your butt off to get it. GG: In our forties, when he was working highway patrol, and I was doing pretty good with the town, things got better. MM: But when you were young with Wendy, you were poor for many years? GG: Yeah, that's why she didn't have near what her daughter has. I think they buy her too much. WG: I told her when she got pregnant, I said, “Don’t buy her every toy that's made. Christmas and birthdays, if she earns something, good. Did she listen to me? Nah. Every damn toy they make (laughter). They’ve already hauled off, I know, three or four bags, big black garbage bags full of toys to get rid of stuff.18 MM: Why do you think we do that? GG: I don’t know. MM: You didn't feel the need to do that. I mean, you couldn't have done it, but it sounds like even if you had had the money, you wouldn't have done that. WG: When I was growing up, I got, I remember when I was eight years old, I got a Strombecker slot car set, played the whiz out of that thing all my years, but when I got done with it, it was taken apart and put back in the box the same way it come out of the box. When we got married, I gave it to her brother. It was in the exact same box, exactly the same way when it was first opened. Within a week, it was destroyed. MM: That must have broke your heart. WG: Yeah, ‘cause that's probably worth some money now; I'd still play with it if I had it (laughter). I loved that thing. Like stuff now, I keep it in a box; I keep the box that it come in, and when I'm done using it, I put it back in the box same as it was. GG: I think that comes just from being raised hard. MM: You knew the value of something; you knew how hard you had to work to get it. GG: Nowadays it’s a disposable world. WG: This is the only toy I'm going to get for a while; I'm going to take care of it. Nowadays, every time someone farts, “Here’s some new toy.” You don't learn to take care of-- you only get one or two, you'll take care of this, ‘cause that's all I'm going to get to play with. Now, they got a whole room full of stuff. That's one of the problems with kids these days. Too much of a disposable world. People don't want to take care of stuff. I've got a little game, a little solitaire game I play. I've taken it apart and repaired it three times. It cost $10, but… We got a hot tub out there we've been thinking about getting rid of; we’ve had it for 20-some years, but it still works. I hate to throw it away if it still works. MM: Do you not use it anymore? WG: Every once in a while. We don't use it as much as we used to, but you are heating water for 102° all year long, and you can turn it down in the summertime, but I'm sitting there thinking I need to get rid of that. I want to build me an outdoor kitchen, but it still working, and I can't get rid of it if it still works. MM: So you're going to build an outdoor kitchen? GG: That’s our dream.19 WG: Because I like to cook outside. I've got a little stove set up and I do spaghetti sauce. I make a big pot. I’ll cook it up, and I'll make a batch of it, I call it a triple batch, a big old pot full of it and we freeze it and come home some evening and say, “I’m tired,” let's follow it and cook some noodles. GG: Yeah, real often he'll make that or— WG: Chili. MM: So you said you did housework as a child, did you also cook? WG: Some. MM: So when did you do this cooking thing? WG: I don’t know. GG: More been in the recent years. WG: She done most of it. She’s an excellent cook, why should I interfere with her cooking? MM (to GG): Did your mom teach you to cook or did you teach yourself to cook? GG: I think I learned more from his mama than I did from my mama. With six kids running around, she didn't have the time. Seriously, I had to do most of the cooking, and it wasn't good cooking, it was fast, and you’ve got to feed six kids. WG: You had to stretch your food out too. GG: Yeah, I had fun with my little hamburgers. WG: When we first got married, she made little dog ball hamburgers. And I’d say, “Damn, woman, get some meat in these burgers. GG: Yeah, you had to feed a bunch of people at my house. MM: Yeah, that's funny. My husband had the same thing. He grew up poor, and when he first started making sandwiches for me, you'd get the tiniest bit of peanut butter, just a dusting of peanut butter or one tiny slice of a thin ham. And I’d say, “Honey, put some stuff on the sandwiches!” WG: When I come up, we killed our own– butchered cows or hogs and everything, so we pretty much had meat. My uncle could take (7:22)—he could take a hatchet and take care of a hog better than some of these guys can with these band saws. MM: No kidding!20 WG: I remember every fall, we’d butcher a hog, and my job—I still got the hog rifle in there— MM: What’s a hog rifle? WG: It’s just a little single shot .22. MM: And you called it a hog rifle ‘cause it’s to kill hogs? WG: Yes, we’d shoot them in between the eyes with it, and then you'd slit their throat, so they’d drain, you wanted to get the blood running. And we had a big 55-gallon barrel with a fire under it, boiling water, and we’d dip him in the water, scrape him, and do all that stuff, and he’d butcher it. I was a little kid, so my job was to help the womens render the lard, and we’d sit up there, and I’d get grease on me and everything. MM: How do you render lard? WG: They’d cut it up and then they’d boil it down, and I just remember having to help them cut it up to do that. Churn butter, done that. I hated that. MM: Why did you hate it? ‘Cause it was hard? WG: Well, you’d sit there, and it would splash up in your face. (MM laughs) But when I was a kid, I didn't realize, that this was good stuff. We’ve still got the butter press in there. MM: No kidding! WG: It’s up there on the shelf in there. MM: I don’t see it. Oh, that blue thing? GG: You never had to do butter or nothing? MM: No, we were raised in the suburbs. WG: You set it on a plug and press the butter in it and you put a stamp on it. MM: Oh, how pretty! That’s so neat. (To GG) Do you do that? GG: I did when I was a kid; I'd churn butter. WG: But I look back on it now, that was damn good eating. As a kid I would take fresh churned butter and Karo syrup and mix it up and put it on a biscuit. I couldn't do it now; it's too rich. But then it was good. And pop, we only got sodas every once in a while, I enjoyed them on a hot day. We drink them things real quick and it'd bring tears to your eyes, the carbonation. Those were good days then. Paul Harris’ store as you start up the mountain going eastbound on to the right over there, I don't know what it is now, there's a little yellow building, that used to be the 21 local grocery store, Paul Harris’ store. He had one of those big Coca-Cola machines, had the water baths with the water running in it. Go over there and get, he had slices of rolled baloney, and you’d get slices of baloney and take it home and fry it up for sandwiches, and it was good. GG: I don’t know if he told you, but he was actually born at home. He wasn’t born in a hospital. MM: I didn’t know that. Really? Tell me about that. WG: If you’re—exit 66, if you're coming out of Ridgecrest, you get on the interstate right up there going towards Black Mountain, about where the entrance ramp connects to the Interstate 40, there's a house, and that's what house I was born in. MM: Why were your born there? GG: Because they couldn't afford to go to the hospital. The two older boys were born in the hospital but by the time Buster come along—I guess he told you, he was a surprise— MM: So who delivered the baby? WG: [I don’t know.] But Mom got sick. GG: She had complications, and she did go to the hospital. WG: I know—I was told I’d stay with some of her friends in Black Mountain ‘cause they used to give me hell too, and talk about the day I used to cry for the moon. I wanted the moon; I'd cry for the moon. Mom was talking about one day before Interstate 40, it was a little two-lane road, and it’s still a different configuration. You used to come up the old mountain, that was the main drag, and one day Mama looked up and cars were stopped, and I was in the middle of the road. And she said, “You’s bound to be a cop.” (Laughter). MM: Wow, that’s crazy. (To GG) So, Genella, you cooked not much good food for the six, and you said Buster’s mother kind of taught you to cook? GG: Yeah, she was just one of them—home-cooked, gravy, biscuits, everything tasted so good. I guess that's what she was raised to cook like that, and so I would just watch her, and everybody loved Mamaw’s cooking. MM: So you kind of picked it up, and then (to WG) your wife became a good cook. WG: Mama, when she was little, was raised a whole lot rougher than I ever was. MM: How? WG: Her mom, she didn't like preachers, ‘cause her (Genella’s) mom when she was little took off with a preacher and abandoned her. I don't remember what my granddaddy did for a living, 22 but he wasn't around so she stayed with family friends in Black Mountain. That's how she got up in this neck of the woods. They’re from South Carolina, her family, the Darnells. So she told me stories many times. I enjoyed talking to her when I was growing up. She told me about when she’d go to the old Coke machine, people wouldn’t drink it, and stick it in the racks, she'd finish it off, and that's the only time she could get a pop, just stuff like that. So she promised herself, I remember her saying that her kids would not be like that. So we didn't have a whole lot, but we had clothes, we had a warm house, food. They took care of us. Beat us, but they took care of us (laughter). But we earned ‘em. Dad was rougher on the older brothers. He kind of slowed down a little bit when I come along as far as the discipline part. MM: Did you have to go find your own switches? WG: Yeah, done that. GG: His dad used the belt. MM: Oh, that’s not good. WG: Yeah, and I think the last time he frailed me— course I earned that one to. GG: My mama was the one you had to go pick your own switches, and you better not come back with no little one. So my brother got spanked and I didn't. MM: ‘Cause you were precious, as I recall. GG: I was. (Laughter). WG: Ask her about her sister, there’s the perfect one (gesturing toward GG). GG: Mostly because I made ‘em mind because I was the oldest. MM: Well, you were the oldest; you had to be responsible for them. Wow, well, you guys had quite a life. You really have. GG: We have. We hung in there. MM: Came up from hard times, you really did. GG: We did. MM: You did well. You should be really proud. WG: Yeah, we used to have some knock-down—some hellacious fights [when Wendy was little], when we first got married, but now our arguments usually last about two minutes, if that. MM: It gets easier, doesn’t it?23 GG: It does; it does. MM: But I’m glad I hung in there because there were many years that (15:14-talking over each other). Yeah, you wouldn’t want to start over. WG: I finally got to [where] I just say sorry, it’s my fault. GG: You should see the raw material I started out with. WG: She said the only reason she didn't leave me was because she didn't want her mama to say I told you so (laughter). ‘Cause nobody thought this [would last]. I had the perfect one and the evil. MM: Opposites attract (laughter). She had a job to do. WG: She’s still working. MM: That’s great GG: Well, it’s been fun, Mary. MM: Me too! END OF AUDIO: HL_HIST474_Martinez_Gray_2018-10-21 END OF INTERVIEW

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

William Irwin (Buster) and Patricia Genella Lewis Gray, a couple from Western North Carolina, discuss how they met and their perspectives on work from different generations. They talk about what each of their parents did for a living, their own jobs through the years, and how their grandparents, parents, and then they themselves instilled work values in their children. This interview was conducted to supplement the traveling Smithsonian Institution exhibit “The Way We Worked,” which was hosted by WCU’s Mountain Heritage Center during the fall 2018 semester.

-