Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (292)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2766)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- 1950s (1)

- 1960s (1)

- 1970s (4)

- 1980s (50)

- 1990s (10)

- 2000s (12)

- 2010s (19)

- 2020s (30)

- 1600s (0)

- 1700s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1860s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 1890s (0)

- 1900s (0)

- 1910s (0)

- 1920s (0)

- 1930s (0)

- 1940s (0)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (84)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Asheville (N.C.) (0)

- Avery County (N.C.) (0)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (0)

- Clay County (N.C.) (0)

- Graham County (N.C.) (0)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (0)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (0)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Macon County (N.C.) (0)

- Madison County (N.C.) (0)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (0)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (0)

- Polk County (N.C.) (0)

- Qualla Boundary (0)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (0)

- Swain County (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (0)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (0)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (46)

- Interviews (25)

- Photographs (23)

- Sound Recordings (21)

- Transcripts (24)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (4)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Bibliographies (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Manuscripts (documents) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newsletters (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Personal Narratives (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Publications (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (23)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (0)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (44)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- African Americans (0)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Artisans (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Cherokee pottery (0)

- Cherokee women (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Education (0)

- Floods (0)

- Folk music (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Hunting (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- Mines and mineral resources (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- School integration -- Southern States (0)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- Slavery (0)

- Sports (0)

- Storytelling (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- World War, 1939-1945 (0)

Interview with Dawn Neatherly, transcript

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

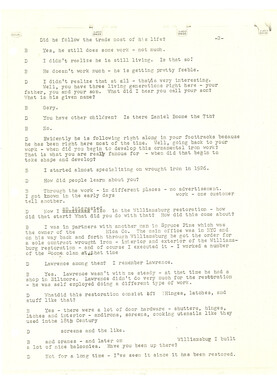

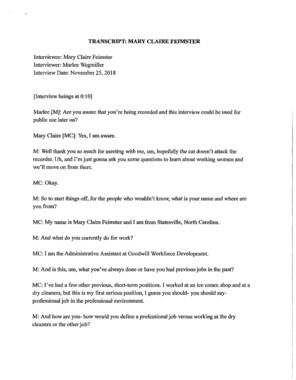

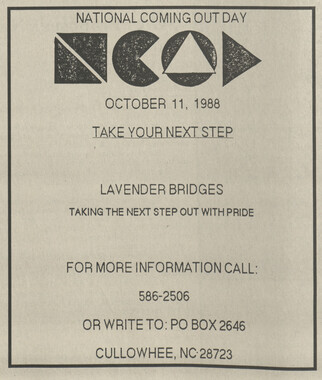

Sarah Steiner: Today's date is February 25th, 2021. My name is Sarah Steiner. I'm speaking with Dawn Neatherly, who was born in 1962 in Orlando, Florida in the United States. Dawn's preferred pronouns are she, her. Dawn has been living in Webster, North Carolina for the last three years. Today we're speaking in Cullowhee, North Carolina. Thank you so much for chatting with us today. I want to start off by just telling us a little bit about who you are and where you're from and your story. Dawn Neatherly: Okay. I'm an air force brat. My dad was a 30 year career military man. He retired when I was eight and we moved back to Morganton, North Carolina, which is where I grew up. Morganton was where my mother's family was from. So we had lots of family there. One of the things that I remember from very early on when we came back to Morganton, I had a second cousin, an older cousin. She was in her 20s probably at that time who was gay. My parents being military, we were just very ... There was a certain liberalness to everybody's thought process. I don't remember a time in my life when I didn't know that there were some women who liked guys, and there were some women who liked girls and vice versa. It was just sort of a common awareness to me. I didn't have any real sense that there was anything wrong or unacceptable socially or anything. My cousin had two very good friends that she played sports with, and my dad and I would go and watch them play basketball and watch them play softball. They were ... One was of Native American descent, dark hair, dark eyes, olive skin. The other one was a classic blue-eyed blonde. I thought they were the dark and light of perfection. I mean, I always thought they were just beautiful and gorgeous to look. They were very classically athletic dykey. I mean, they weren't pretty by normal standards I guess, but I always thought they were both just gorgeous. I can remember being six, seven, eight years old and saying that to my mother and my mother would be like, "Well, whatever your taste is." Kind of thing. I didn't think much about it. I don't remember ever having any sense that there was anything odd or different. So I didn't really have a coming out per se. One of my dear friends in high school, her older sister who was considering probably older, she was in her late 20s, early 30s was very political. She had lived in California and she'd lived in New York city, and she was very involved in the women's movement. She'd been very involved in the gay rights beginnings in the '70s in New York. Very educated, very academic and she was just brilliant. The sister was also gay. My friend kind of stumbled into a relationship doing summer stock with someone that was a woman. When she came back from summer stock, she told the two of ... We were a threesome of people that hung out together. She told the other two of us that she was dating this woman. Of course she told her sister. Her sister's name was Lisette. Lisette was like, "Hey, this is not about sex. This is about culture. You need to read this, you need to listen to this. You need to know this bit of history. You need to know that bit of history. If you're going to identify as being part of this community, you're not going to do it just because of who you're sleeping with." Lisette was just throwing books at her and music and telling stories and embodying all this history into my friend. The other one girl that was part of our little group of people was someone that I had just always thought was gorgeous and loved being around. Then after Jan had come out to us, Susan, and I just got to talking about it and it was like, we realized we both sort of had that same sense of attraction and it just sort of went from there. There wasn't any of those kind of horror stories that people tell or self-doubt or concern. I honestly didn't know that it was a big deal. I really didn't. By the time I came to college, because this all happened when I was a junior, by the time I came to college, I had been dating the same woman for a couple of years. I had had the benefit of everything Lisette had given to Jan. I knew all kinds of history, all kinds of cultural icons, all kinds of music and books. Which is why I grabbed a couple of these CDs when I was heading over here, because in the late '70s, there was a real rise in what was called women's music. Two of the really big stars where Cris Williamson and Meg Christian. Lisette of course turned us on to their music and gave us albums and I had turned them up to CDs now. I was reading Rita Mae Brown and I was reading Sappho and I was up to date on the Stonewall stuff. I mean, I just had all the ... I was some kind of a nerdy academic person anyway, but I had all this cultural stuff. When I showed up at Western, in my freshman year, which was the fall of 1980, I had left a girlfriend at home because she was a year younger. But I showed up with this stack of record albums and books and all this stuff in my brain and realized that there wasn't this academically obvious community of gay women that I guess I thought were just going to appear magically. Because the way Lisette talked, it was like academics and all this, you were just going to be able to walk down the street and go, "That must be where the lesbians are." It wasn't like that at all. That was really weird. SS: You came to college here? DN: Yes. SS: At Western. DN: I went to college at Western. SS: Yeah. DN: I had done summer camp here for years, and so it was a nice transition to come here. Having done summer camp, I knew the campus, I knew my way around. I was comfortable. I had all this other stuff going on in my mind. It didn't take a lot of sitting in the cafeteria or walking around on campus to see that there was a really strong lesbian presence on this campus. Most of them were your more athletic jock dyke type women, but it was evident. It was just kind of a matter of how do you make that connection. Because once I got here just by hearing people, making comments and things that were said in the dorms, I was exposed for the first time to people that were incredibly negative about sexuality. That were insulting and used slang and accused people of things and I'd never encountered that. That was really different. SS: How frequently did that come up when you were here? What years was that? DN: I came in the fall of 1980 and graduated in the spring of '84. Then I came back in fall of '86 and graduated in the spring of '89 with my masters. To answer your question about frequency, before I made that connection to the community here, it was just kind of your common things. If a girl wasn't particularly feminine, somebody would call her a dyke. If a guy was ... People would talk about how the whole theater department was full of queers. Just those kinds of things. It was very broad, very negative, not particularly violently negative, but just negative. You just would hear it. Then once I touched base into the community, you heard it more because we were kind of hiding in plain sight sort of thing. I remember, it was probably spring of my sophomore year, I think ... Yeah. Spring of my sophomore year. I had been connected with the community since fairly early into the year before. I lived in Scott. I had come out of Scott and crossed the street that used to be there. I was walking down, headed to the walking trail that's still there around down in the hollow down there. I was headed to walk. In shorts and T-shirts, no big deal. I was headed to go walking and a pickup truck came up the road from the entrance with a whole bunch of obviously drunk guys piled in the back of the pickup truck. Windows down and whatever, and somebody yelled something about, "That's one of those damn dykes." Somebody else yelled something about, F-in’queer something. Then they threw a couple of glass beer bottles at me. Now they were coming from campus, they were going down. They were by me. Because they were on the right hand side, they were right next to where I was walking. I'm just kind of startled and obviously it's like, that's glass beer bottles. That's kind of scary. They went down to the turn below the track and turned around and started back. I was terrified. I went running into Walker because it was the closest place I could get to, and went to a friend's room. Because I didn't know what they were going to do. That's probably the only time I really felt violently scared on campus. Generally, we pretty much got left alone. But I do remember that very clearly. It was the awareness, something that I kind of noticed and I hope it's not still true, but I know it was true in the early '80s. If people knew that you were a gay woman and you were any resemblance of attractive, you would deal with guys that thought they were either trying to convince you they were going to convert you or these guys that I wasn't sure they weren't going to just drag me in the truck and rape me to convert me. That didn't happen if you were ... I use this phrase because it's easiest description. If you were the really classic diesel dyke that didn't even hardly look like you were female, you wouldn't get bothered with that kind of behavior. You might get called names, but there wouldn't be somebody threatening to cure you. That was kind of weird. I noticed that we all migrated to a real androgynous look. It was like as much as you could get to that point, it felt safer. If you could get more androgynous or more masculine looking. Which I know looking at me now is hysterical, it's like, "How could you get close to that?" But if you look at that picture, I mean, you could do it. It was quite doable. SS: Sure. Yeah. How long did that persist for you, post-graduation or just while you were here? DN: Well, it kind of has to tie in to answer that to a more political sense. In the late '70s, in the early '80s or into the '80s, really, the gay community, there was no room to be bisexual anywhere. If you were bisexual in the straight community, you were just experimenting or you're silly, or that's just a phase or God knows what. If you tried to be bisexual in the gay community, you were a fence-sitter. You were trying to have your cake and eat it too. You weren't willing to take the risks of admitting to what your sexuality was. You just could not be bisexual. You just could ... I think ... That's how I self-identify. I self-identify as bisexual. But in the early '80s on campus, you couldn't. I mean, if you wanted to be part of the lesbian community, it was all or nothing. I lived in that space for two years. My sophomore year, I happened to meet a guy that I thought was attractive and agreed to go out with him and very quickly was ostracized. You're not welcome. You're a traitor, whatever. At that point, I sort of was like, "Well, screw that. Then I can be as feminine as I wanna to be. If you're going to throw me out anyway, then I don't have to worry about keeping this androgyny thing in play." I was more balanced in that I think. But I think I've never been particularly girly. I don't find that ... Maybe because the women that I was attracted to early were all athletic and all the women that I knew in college and women that I dated later in life, somewhere in there, I associate really feminine with weak. It's an unfortunate thing and I know it's not fair. I try very hard not to do it when I look at other people, but I still feel that way about myself. I will be professional. I will be casual. But I don't particularly have any desire to be femme. SS: Sure. What did you study while you were a student here? DN: I have an undergraduate degree in philosophy with a minor in Poli Sci. SS: Yeah. What about the graduate degree? DN: Mental health counseling. SS: Yeah. DN: Yeah. SS: Okay. You mentioned before we were recording maybe some extracurricular activities too, was that you or your friends, I'm thinking of sports or really anything? DN: Well, I've always been one of those people that I was lucky to walk and chew gum without falling down. I was just never athletic, but I love sports. My daddy started carrying me to basketball games when I was three. I grew up going to watch sports with my dad and loved sports. I was the dedicated fan. But it was a very common ... In the early '80s, the women's volleyball team played in Breese Gym. Breese Gym at that time had half a set of bleachers and the other half was offices and a gym floor, and that was it. It might've maybe 100 people could be seated in it. If it was a home volleyball game night, if you wanted to find the majority of the lesbians on campus, you could just go to Breese. We were all there. Everybody went to watch the games. Everybody went to the basketball games. The basketball games were a lot more mixed because the women's basketball team played right before the men did in Reid then. You would have people coming in. The crowds would get more mixed. It was less open. When we were at volleyball games, it almost was as comfortable as being at the bar. It was just a room full of lesbians watching a ball game full of lesbians, being coached by lesbians, very much so. Then softball, they played softball on one of the old intermural fields. They didn't have a dedicated field yet, and it was the same way. I would say 85 to 80 ... No. 85% of the women who played in the three major sports, volleyball, basketball and softball were gay. Then Western always has had a really, really strong intramurals program. In the intramurals program, there were a couple of women's intramurals teams that it was a rarity for a straight woman to join that team. If there was a straight woman on that team, it was because she was really good at whatever they were playing in that particular league and somebody recruited her. The two teams that I remember from the '80s that had a large lesbian population were the Lucky Losers and the Turkey Squats. Fun names. You had that connection. But I think going to sports or participating in sports was certainly defining in some ways. But I think the thing that really defined the community was the social aspect. There was a gay bar in Asheville called the Cabaret. It was right across the four lane from the Civic Center on Cherry Street. I don't know what's there now, but that was the active bar at that time. Thursday night was ladies night. There would be anywhere from 15 to 25 or 30 people from Cullowhee. We would carpool. You'd be calling around, starting at lunch on Thursday with who's driving tonight? Who's going to go? It was still very ... You dressed up to go out. The look at that time was either pleated slacks or jeans, and cowboy boots with cutaway heels, and button up shirts, blazers, neckties a lot. You dressed. I mean, you dressed up to go out. If you're going to the nightclub, you dressed. Every Thursday, there'd be this humongous group of us that would drive to Asheville. You get there 9:30, and they shut down at 1:00 or 2:00. Then you drive back to Western and attempt to go to class on Fridays. Most of us didn't have morning classes because of it. Then Friday evenings would end up being something very personal. You'd get together with a bunch of people in their dorm room and sit around, or you might go to somebody's apartment. But it was very laid back. Then Saturday night, everybody went back to the bar. Saturday nights was just an open Saturday night. That was one of the rare times when you would see the male gay population at Western. Because I look back and they were horrendously closeted on campus. I think, in all the time I was here, I might have known a handful of gay men. Now, I might've seen more at the bar that I recognized from being on campus. But if you walked up and spoke to them, they would walk away from you. I always got the impression that it was a lot more dangerous and a lot scarier to be a gay man on this campus then. We were just kind of all having a good time running around, looking like little cute menswear dressed dykes, having a great time and not really thinking about it so much. I think we were dangerous to them, because it was that guilt by association thing. If you're even a hint that you might be a gay male and they see you hanging out with all the jock dyke, so we didn't interact. Very, very rarely interacted. If we would see them on Saturday nights at the bar, most of them wouldn't speak to us. We would be like, "I know you and you know me, but we're not going to talk about this." Even though we were inside a gay bar. That was really different. SS: Yeah. Interesting. What happened when you left Western? DN: When I left Western. SS: Yeah. DN: Well, like I had said, I was dating a guy for about a year and a half, well, yeah, my junior and senior year. Then right toward the end of my senior year, he had already graduated and that was kind of going downhill. I encountered this woman that was just amazing, so fascinating. She was younger. The community was switching. Into the mid '80s, it was becoming more evident you were seeing more people that were more androgynous than dykey. You saw lipstick lesbians, quite a bit of them even. I met this woman that was just amazing and fascinating. We ended up seeing each other for awhile. Then I went to law school for a year and a half. You don't date in law school. You're lucky if you eat in law school. The graduate school is just such a horror, and I hated it, left. Quit in the middle of the semester. Got up the next morning and called a woman who was the Dean of students here at that time. She was a great mentor of mine and said, "I just quit. Now, what the hell am I going to do?" She was like, "Well, the first thing you're going to do is get in the car and come home and then we'll talk about it." I drove back up to here and sat down with her and we talked about what I was interested in. She said, "I'm going to send you over to the counseling department." I was like, "I'm not crazy." She said, "No, I'm not sending you to the counseling center. I'm sending you to talk to the people that do the master's degree." She said, "You love to solve problems. You're very orally ... You want to talk, you like to communicate. The things that made you think you could be a lawyer will make you a good therapist." I got into the counseling program here and kind of connected back into the community, which had changed for the better. It was more open. It was a little more relaxed. Then when I graduated, somewhere in there, I had started a relationship and it ended up lasting about 12 years. When I graduated and left Western, I left with my partner and we moved down to the middle part of the state. Like I said, we were together for about 12 years. Then from that, I actually ran up on another one of those men that want to convert you and actually ended up getting assaulted this time. It may seem really weird, but in my own mind, this made sense. I look back on it now and it's like, "I don't know where that came from." But having been sexually assaulted, I was like, "I'm going to become Donna Reed. I'm going to marry the nice guy that I knew back in high school, and I'm going to do the church thing and the social thing. I'm going to be Donna Reed. Nobody can hurt me if I'm Donna Reed." I got married to a guy I had known since I was in high school and he'd always known I was bi. So it wasn't a big deal in that sense. We got married. It lasted about nine years. But long enough for me to get healed enough to realize that I married him because I was trying to run away and hide in a '50s sitcom. From there, I just kind of moved on in different aspects of my life. About seven, eight years ago, met my current husband who had much the same kind of life that I had had in that he was bisexual. He had, had spent a lot of time experimenting and playing and kind of feeling out his whole sensual sexual identity. He was a history geek like I am. We met at a Renaissance festival. Just a wonderful kind loving man who is very comfortable with a very strong woman. I mean, he will tell you our home is a matriarchy and that's just the way it works. Then when I retired from being a mental health counselor, he was like, "What do you want to do?" I was like, "I want to go home. I want to get back to Jackson County. I want to go home." So that's how we ended up back here. SS: Where were you practicing? You said- DN: I worked for the state. I worked in the prison system and in the public school system. SS: Really? DN: Yeah. SS: Anything you'd like to share about that? DN: It goes off in a whole different direction than my sexuality conversations, but yeah. I spent 10 years working at the only youth facility for males in North Carolina. At that time, you could be adjudicated as an adult at 15 if the crime was severe enough. We had every felon aged 15 to right before 21 in one facility. Most of them were there for being feloniously stupid. You had a few. There were a few guys that they would come in the door and you would look at them and go, "Can we just go ahead and ship them to Central Prison in Raleigh because that's where they're going to end up?" But most of them were just dumb kids. Most of them had quit school, through their life in with gangs or with just stupidity. What we tried to do was give them a sense that, you are still young enough that you could have a second chance. You could go back to your education. You could find a way to turn your life around and move forward. In that aspect, it was a wonderful experience. The part that was really hard, the whole state of North Carolina, majority of our population were persons of color. Weren't a whole lot of white boys. You could look at the records and easily see two young men who committed almost exactly the same crimes in almost exactly the same manner, and they didn't have the same sentences. That was insightful to realize that. I had always been ... My interest when I was working with the public schools was at risk kids, people with learning disabilities, poverty, broken homes, gangs. All the things that impacted young people and messed with their ability to get where they needed to be educationally. I was always very ... When I took the job at the prison, I was like, "This is the ultimate at-risk youth." They were already incarcerated for it. I kind of expected some of what I learned from it, but it was telling to see how much race plays into it. Then to talk with the people who worked at women's prison and discover how much gender plays into it too. A teenage girl with a first offense, a felonious B&E, was probably going to get a slap on the wrist. A guy, especially a Black guy, was going to do jail time. That was an interesting experience. I enjoyed it. I would have stayed there even longer, but the people who were in power in the state at that time ... Well, first they did a good thing. They passed a law that said you cannot be adjudicated as an adult until you're 18. You have to be treated as a minor, no matter what the crime was. That was a good thing. But then they decided since they changed that law and everybody that was going to get adjudicated was at least 18 years old, you didn't need a separate youth facility anymore. They could go into regular pop. So they closed our prison. SS: I see. DN: We fought. God, we fought. But it was a conservative Republican government in the state and they wanted to say they were saving money. That was what looked good, not what they were doing for people's lives, in my opinion. I retired a little early, 25 years instead of 30. We moved back to the mountains. SS: That was about three years ago, you said? DN: We actually originally went to Cherokee County. We were in Murphy for a couple of years. When I said we were going to ... When we decided to come back to the mountains, I was looking for something to do because I really wasn't ready to retire after 25 years. I was offered a position developing a day treatment program for high school students in Cherokee County with the public school system. It's a wonderful program. I had great time developing it, getting the program written and getting it planned and getting it up and in gear and had some good successes with it. But I mean, they hired me to set it up. Once it was set up, I was kind of like, "Okay, I'm ..." I really wanted to be here. My husband got an offer from Lowe's to come to Sylva to drive for them because he was a truck driver. He was like, "You'll have to leave your job." I'm like, "I've done what they hired me to do. Anybody can run it now. Let's go. I want to be back in Jackson County. I want to be as close to campus as I can get. Let's go." Came back here. I think I stayed home being retired for six months, maybe a little bit longer, and I was bored out of my mind. I was looking for something to do. I saw an ad in the paper that, the non-profit that I'm now the executive director of was looking for a full-time professional executive director. It's an anti-poverty initiative called the Circles of Jackson County. I interviewed for the job and got it, and that's where I've been for these past three years. SS: Yeah. Tell us a little bit more about Circles. DN: Circles is based on a national plan that was developed by our founder, who's out in Utah. That combines the idea of people pulling themselves up by their bootstraps and people making use of the benefits available to them. We're not a crisis program. We work with the working poor. The analogy that I always use when I'm talking about it to people is, we don't pull people out that are drowning. We work with the people who've gotten close enough to shore, that their head is above water, but they're still standing in the mud in a nasty pond. We want to get them out of the pond. The way it works, is they come into our program, they do a 15 week, one day, a week training component that addresses psychological, sociological, environmental, geographic and racial issues related to poverty. How you get in the position you're in and how you do have responsibility for some of your own thought processes and things that go with it. Not in a blame sense, but just in an understanding of where you're at. Then at the end of that 15 weeks, we match them with two or more allies who are middle-class or they are people who have gotten out of poverty. Middle-class is just the safest way to put it. They're very specifically in highly trained, so they understand all the poverty issues and what goes with it. For the next 18 months, that client and those two allies meet at least once a week. They develop goals, they do planning, they address issues. What we try to get across to our clients is, nobody's asking you to go cold turkey, drop every benefit you're getting. What we want you to understand is, it's a system and you can make a plan that will let you work your way out of that system. A lot of people don't know this, but all of the different government benefits like food stamps and Medicare or Medicaid and HUD and all the other things that you can get, they don't have a universal income limit. They all have different income limits. If you make this much money, you stop being able to get this service. But over here you get ... Like HUD is wonderful. You can pretty much get to a living wage, which is about $15 an hour around here, and still have some HUD benefits to help with housing. Food stamps is the worst, they're gone like that. What we teach too, is that there's a whole community of programs that are not tied to those government regulations. You can take that job that pays enough that you lose your food stamps, because we have the community table, and we have the food banks and we have all these programs. It will carry you over while you get to the next point. We've been very pleased. We've been here six years. We have clients who were in our first cohorts who are ... One of them is on our board of directors now. Two of them are trained mental health professionals working back in the community. A couple of people that own their own businesses now. When COVID hit, not a single one of our active clients backtracked on benefits. They took the COVID benefits that everybody got, but they didn't apply for food stamps, they didn't apply for anything else. They had a plan, they had an emergency savings account that we helped them to establish, and they got through it. I'm very pleased with that. It's neat because it kind of ties back around into that circle. Because I know I told you when we started that I was a little nervous. Because the community and the place and time that I grew up in, your sexuality was something that you hid. It just was, unless you were straight. Being the executive director of a major nonprofit, that's a very, very visible job. It's helping me ... Wanting to do this interview partially was just to work on the mindset of we're in a different time and place now. Whatever my sexuality is, doesn't impact my work. I have been open with clients since I took this job who openly identify and their radar is going to go off on me anyway... They're looking at me like,"Are you in a closet? Are you stupid or you lying?" I'm like, "I'm not lying." It's been a good growth process seeing these people today and seeing where these young people are at now. Working in the nonprofit has been really helpful with that because it helps me to see just how much the world has changed in 40 years. When I was an undergraduate here at Western, I did not know a single person who was out to their parents. I'd say I knew 50 or 60 people on this campus that were part of that community, and no single person that was out to their parents at all. Most of my friends were going into education and they anticipated that they were going to spend their entire career hiding because there was a morals clause in teacher's contracts. We all just kind of thought we were going to spend our lives lying and hiding. I remember the first parade I saw and it was in Asheville. I didn't march in it, but I went and I was just shocked that people could be that open, could be that comfortable. SS: Do you remember when it was? DN: I beg your pardon. SS: Do you remember when it was, roughly? DN: Let me think for a second. I was in grad school. SS: Sure. DN: '88 maybe, right around there. SS: Okay, cool. DN: Right around there. SS: Yeah. DN: Because I actually saw one of my exes was marching and I was just like ... She was more shocked to see me because she was like, "I can't believe you're actually here." It wasn't that ... You're just afraid. You don't know what people are going to say. You don't know what's going to happen. People are still, even as open as the world is, there's still this amazing ... Parents are not always ready or able to see where they're at and what's happening. We knew a young girl while we were working at the Renaissance festival and she was 15 and very interested in the whole festival thing. She had known that she was gay, openly known it back to about 11 or 12. Came out to her mother, the whole world. She's just very public about it. Her mother continued to argue and fight and suggests that she could fix it and that it was a phase and that ... I mean, it was just ... I mean, she didn't kick her out straight, but the psychological damage of being denied by your parent constantly, this young woman was just a mess. She kind of found her way to our little circle of people at the Renaissance festival and just kind of where that matriarchy part of me came from. I was very much ... When you get to also be in costume, you really get to be a matriarch. One of our other friends knew this young woman from working in theater. She brought her one Saturday to festival and brought her down where we were all hanging out and was like, "This is so-and-so and she's really interested in Ren fairs." She had this cobbled together costume that was kind of sad, but she tried. Her friend told us about how her mother was always on her case and she didn't feel like she had any identity. Nobody would accept her for what she was and she was hoping that we would. One of my jobs as the matriarch of that group was, I gave people their names. Then we said, "Bring her back next week. Just bring her back." All of us scavenged all of our closets, put together a full costume that was just perfect. She came back the next week and we drug her off to the nearest clothing booth where we knew the owner and said, "We need to use your dressing room." Shoved her in there and said, "Get dressed." She's like, "What?" We're like, "Just get dressed." She puts all this on and she's just thrilled. We're like, "These are yours. These are gifts. These are from our closet. This is your first full costume." Then everybody ... She's just overwhelmed and people are standing there and she's like, "What?" They're like, "You haven't been named yet. You're going to get named now." I named her Rogue and she loved it. Rogue was perfect for her because she had been a rogue forever. We got to watch this young woman, 16, 17. By the time she was a senior in high school, she wore a tux and took a female date to the prom and was able to do that. The school didn't care and her mother was finally calming down. See, there's always a story. There's a story everywhere you look. There's a story in every young person you see. I think a lot of people believe that because it's so open now and everybody talks about it, and every TV commercial you see either has a gay couple or a mixed race couple in it, that it's simpler somehow. But you still have to deal with the emotional aspects and how your family takes things and the dumb, biased, redneck attitudes that you encounter. But I think ... You asked me about this being a rural community at one time. I was thinking back to the way I was raised, and my parents are first generation down the mountain. They both were Appalachian, born and bred long-term. I don't know so much about being male, but being female and gay in the Appalachians is just not a big deal. That's that strong, independent spinster woman. She looked after her parents until they were dead. Now she's so used to it, she's just going stay on that farm, I mean. I think maybe that's part of why this community that we knew even in the '80s, even though occasionally we were scared, there was a certain, "She's just one of them women." It was a little more comfortable because of it. Western was very regional then. I mean, you might have students from Charlotte, but it was very regional. SS: Okay. You've mentioned a couple of things relating to sort of community and social life. The first one was, when you were here and you said you started dating a guy and sort of were maybe ousted a little bit from your group. Then the Renaissance fair group. Can you talk a little bit more about that? About sort of evolution of social life maybe here in this region and any groups that you may be a part of? DN: Yeah. The aspect of not being able to be bi, it was just the way the community worked. With some people, it was negative. There was a couple when I was here that were the out lesbian couple on campus. They were almost like, not recruiters in the sense of trying to convince people to be gay, but recruiters in the sense that they just wandered around campus and spotted people and brought them into the fold. One of them was very, very angry at me when I started dating this guy. She was very angry because when I had come into this community, I brought something they hadn't had before, because I brought the cultural stuff. That cultural stuff had just not been a part of this community. It was social, it was sexual, but it wasn't really cultural. I brought that in. I think that's part of why I got a lot of anger from ... Because it was like, "You're the one that's preaching history and teaching this and doing that. Then you go off and do something against us." That was tough in that sense. But at the same time, it was almost a ... There were people in that community that thought I was making a mistake because I was dating this guy. Or something had happened to scare me or something. They wanted to save me in much the same way that straight people want to save you from being gay. I showed you the picture of that woman that I said was the most beautiful woman in the world to me. That's literally what I call her to this day. She turns bright red when I do it, but ... Several of the women in the community on campus sent her to see me to try and talk me into the fact that I was making a mistake. Because they all knew that I was just dumbfoundedly overwhelmed with her and would never ask her out. I was terrified of her. But I mean, they literally pulled her aside and said, "You got to go talk to Dawn. She's making a mistake. She'll listen to you. She thinks you're incredible." She was very comfortable. She was like, "I want you to know I was sent here to tell you that you're making a mistake." I'm like, "What? Okay. Whatever." I never lied from high school on. I never lied. Not even lied, I never hid with any man I went out with. If I went out with a man, I told him exactly how I self-identified from the get go. Usually what I got was, "Well, don't tell anybody else that." Like I had said I had herpes or something. He goes, "Don't tell anybody else that." But I understand the reaction of the women's community here. It's hard to be different. The world was getting more and more conservative in that weird time in the early '80s. I had gone out of my way to kind of create an identity for myself as the cultural history person. They felt like I abandoned them, and I get that. It's much easier today. That particular woman that I was telling you that was incredibly angry with me, we're actually friends again. We reconnected on Facebook and we've chatted about that quite a few times and she's like, "You just didn't ..." It was like being bi didn't seem real. It's like, "We didn't believe it." It was like, you couldn't be on a scale. You had to be on one side or the other side. It was just that. It was just kind of where the world was. Yeah. This community, like I said, 60, 80, I don't know, it's a large group of people, we lived together, we ate together. We went out together. We went to ball games together. We were just so close. Today, if I wanted to go to the bar with my friends, I could take my husband and nobody would care. It's just the world's better in that sense. It's much better. As far as the Renaissance fair community, somebody once told me that people who were part of the Renaissance fair community are highly educated carnies. SS: Yeah. I like that. DN: They want to be independent and free and live their lives without all of the social strains and the requirements of a mortgage and all this other stuff. Yet they're very intelligent. They're very much about a financial thing. Or not a financial thing, they're about the history. They're about having a good time with what they're doing. That community is completely open. The only thing that you can't get away with in the Ren fair community is hurting people. Otherwise, they don't care. My first husband is part of the community also. When he and I divorced, one of our friends sat us both down and said, "Look, you have one of two choices. You're either going to be completely civil to each other because you're both part of this community, or one of you is leaving. Because we're not going to have this stuff here. It's not the way it works." Sexuality and gender identity and all that kind of stuff, it's just like, who has time or cares in that community. They just don't. It was a nice natural place for me to sort of end up in that progress of my life. The mountains are a very spiritual place. It's got this immensely strong, strong Celtic vibe because of all the Scots-Irish. There's a lot of magic and a lot of ... It's a place where you can be a strong, independent, powerful, spiritual woman. Now, there's also some redneck jerks that don't like that, I mean, but you can be. I mean, I know an awful lot of wise women in these mountains, in these hills. I know a lot of people that have a strong spirituality and an old religion feel that have a commitment to an image of woman that is strong and powerful and resilient. I think it tied in well to the struggle that all of us as young women were going through to see ourselves sexually and culturally in that 18 to 22 age group. It was just a good place to be in that you could drive down the Little Canada and find the granny woman that would tell you all about what you needed to do for whatever, and would be like, "I don't care who you're sleeping with." There were these beautiful, beautiful, wise women and tribal leaders in Cherokee. You had that ability to look at a society that had this great respect for a matriarchy. I don't think it was as bad as a lot of people try to make it sound. You just had to embrace the culture a little bit. You would meet the most interesting people, and it's still true on this campus. Even as big as we've gotten, I still meet the most unique people just wandering around here and they're sitting in a ... That classroom that I talked to on Monday, there's this young woman, and it immediately set my radar off. I was like, "This woman is obviously not a traditional sexuality, whatever it may be." She was talking about how she'd grown up in poverty and she had this wonderful opportunity. She knew that she was a unique person and she wanted to share that and give it back to her community and other people. I'm just like, "Wow." It's just I'm an avid, avid Catamount. I have exceptionally purple blood. I believe in what we do here. I believe in everything we do here. The article that was in the paper that made me send you the email, they were talking about Lavender Bridges. I remember that. That was when I was in grad school when that was founded. I remember that and I remember ... What was her name? Was it Sherrill? No. Cris Delgato. That's the woman that founded it. Cris Delgato. She founded Lavender Bridges. Let me tell you about this campus. Do you know where the first meeting place for Lavender Bridges? SS: No. Where? DN: The Catholic student center. The Catholic student center. The first community gay and lesbian organization met in the Catholic community center because the campus priest and the group that were, they were just like, "Not our job to judge you." That was where people met. It was very small. SS: Yeah. Did you attend the meeting? DN: Yeah. I was in grad school then. Well, and also since I was working on a counseling degree, I also co-facilitated the gay and lesbian therapy group on campus through the counseling center. So there was a professional, just sort of general topic open group that ran through the counseling center. I got to co-facilitate that in my second year of grad school. Then my final internship, I got the counseling center internship here on campus. I actually ran the group at that point. In the mid to late '80s, there was already on this campus, a real presence of providing support, of providing information, of being open about the fact that we have students that are in non-traditional, whatever and we need to be aware. Which I don't know what that was like around the rest of the country at that time. I'm not really sure. But I remember thinking, "Don't count us out as being some backwater school here." We have a student organization, we have support groups, we have visibility at the campus group that ... What do they call it now? Valley Ballyhoo. But it wasn't Valley Ballyhoo then. It was a strong presence then. I don't know what happened to Cris. She was stuck around here for a while, but I don't know if she's still in Asheville area or not, but her name is Cris Delgato. I remember that. SS: Anything else you were really hoping to share that I didn't touch on? DN: Gosh, you see, I thought about so many things. I was stories in my head and thinking about the community and the people and the way we did things. It was a safe, comfortable place. Well, no, I know. There's also a very strong faculty presence, even back then. SS: Sure. Yeah. DN: They went out of their way to stay out of our way, which I understood. But everybody knew who they were. It wasn't like ... They were several women. One in the health and PE department, another one surprisingly in home economics. One in administration that you could talk to. I mean, if you were concerned or you were trying to think through the process of what was going to happen. I know a lot of my friends that were going to be teachers spent a lot of time talking to this particular person in the health and PE department about how are we going to spend the rest of our lives hiding, and how do you do that? How did you do this? What do we face? What's it going to be like? There was mentoring there. You just didn't talk about the fact that the room was full of lesbians, if that makes any sense. It was kind of a weird mentoring. We didn't have ... There weren't a lot of ... I don't remember anybody dating a professor or dating a teacher or doing any of that kind of inappropriate stuff. We had one basketball coach and she got involved with one of her players and she was warned. She didn't break it off. The women's athletic director showed up at her house at 5:30 in the morning, yanked the student out of the house and told the coach to pack her bags because her job was gone. She was fired the next ... She was just, poof, gone and nobody talked about it. But what's funny I remember about that, was within the student community, the students were really angry at the student that was dating the coach. Because they were like, "Basically you a dumbass. You knew that wasn't okay. You knew that wasn't appropriate. You created a situation where the AD, who was also a gay woman had to throw you out of another ... You could have created this horrible situation by being dumbbutt." Everybody was very angry at her about it. Very angry. I remember that. But that was more about, we have this good thing here and we have these ... You protected each other, I guess. There's a real connection now. I've reconnected on Facebook with a lot of the people that I knew from back in that time. We're all pushing 60. Most of us are retired, our lives are very different, but there's still that connection. You'll always be part of the community at Western, and that was an important thing. Weirdly enough, even though there's not a gay student alumni association, there might as well be because we're all still very big supporters and all that. SS: Okay. Thank you. DN: Thank you. That was fun. SS: That was great.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Dawn Neatherly talks about growing up in a liberal family and not being aware of issues surrounding sexuality. She attended Western Carolina University from 1980 to 1984 and again from 1986 to 1988 and talks about the lesbian and gay culture during that period, Lavender Bridges, and her own experience being bisexual. She worked for a time in the North Carolina prison system and shares her first-hand experience with gender and racial inequality within the system. Neatherly shares her recent work with Circles of Jackson County helping people to obtain financially security.

-

.jpg)