Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2683)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (15)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1295)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (1794)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2393)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1886)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (147)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1664)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (233)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (478)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3522)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4692)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (21)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (9)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (211)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (981)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2017)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (247)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (68)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (184)

- Envelopes (73)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (811)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (619)

- Maps (documents) (159)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (5651)

- Newsletters (1285)

- Newspapers (2)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (12982)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (5)

- Portraits (1654)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (151)

- Publications (documents) (2237)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (1)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (15)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Vitreographs (129)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (198)

- Cataloochee History Project (65)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1314)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1744)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (388)

- Appalachian Trail (32)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (166)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (110)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (1830)

- Dams (94)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (60)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (905)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (154)

- Hunting (38)

- Landscape photography (10)

- Logging (103)

- Maps (84)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (69)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (245)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

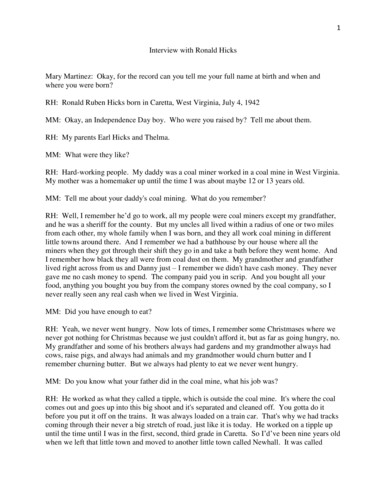

Interview with Ronald Hicks

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

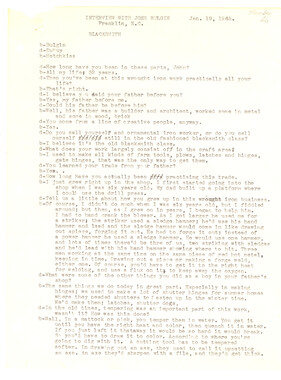

1 Interview with Ronald Hicks Mary Martinez: Okay, for the record can you tell me your full name at birth and when and where you were born? RH: Ronald Ruben Hicks born in Caretta, West Virginia, July 4, 1942 MM: Okay, an Independence Day boy. Who were you raised by? Tell me about them. RH: My parents Earl Hicks and Thelma. MM: What were they like? RH: Hard-working people. My daddy was a coal miner worked in a coal mine in West Virginia. My mother was a homemaker up until the time I was about maybe 12 or 13 years old. MM: Tell me about your daddy's coal mining. What do you remember? RH: Well, I remember he’d go to work, all my people were coal miners except my grandfather, and he was a sheriff for the county. But my uncles all lived within a radius of one or two miles from each other, my whole family when I was born, and they all work coal mining in different little towns around there. And I remember we had a bathhouse by our house where all the miners when they got through their shift they go in and take a bath before they went home. And I remember how black they all were from coal dust on them. My grandmother and grandfather lived right across from us and Danny just – I remember we didn't have cash money. They never gave me no cash money to spend. The company paid you in scrip. And you bought all your food, anything you bought you buy from the company stores owned by the coal company, so I never really seen any real cash when we lived in West Virginia. MM: Did you have enough to eat? RH: Yeah, we never went hungry. Now lots of times, I remember some Christmases where we never got nothing for Christmas because we just couldn't afford it, but as far as going hungry, no. My grandfather and some of his brothers always had gardens and my grandmother always had cows, raise pigs, and always had animals and my grandmother would churn butter and I remember churning butter. But we always had plenty to eat we never went hungry. MM: Do you know what your father did in the coal mine, what his job was? RH: He worked as what they called a tipple, which is outside the coal mine. It's where the coal comes out and goes up into this big shoot and it's separated and cleaned off. You gotta do it before you put it off on the trains. It was always loaded on a train car. That's why we had tracks coming through their never a big stretch of road, just like it is today. He worked on a tipple up until the time until I was in the first, second, third grade in Caretta. So I’d’ve been nine years old when we left that little town and moved to another little town called Newhall. It was called 2 Newhall. And Daddy went to work for a mine there and I was in the fifth and sixth grade there and we lived in what we call second bottom. There was first bottom, second bottom, and third bottom. And first bottom was when you first come in the little bitty town. Across the little creek was first bottom. I had cousins that lived over there. And the second bottom is where we lived. I had uncles that lived in there with us. And third bottom was where the Blacks lived. You know that's where they stay there. And he worked there for two years. MM: On the tipple still? RH: No, he worked in a coal mine; there wasn't no tipple there. Coal was just brought out and loaded on the cars. And I remember a big tunnel. I had a little dog there; his name was Sport. First little dog I ever had, mean little devil. He hated Blacks. They come down and teased him through the fence. Somehow, he got out of the yard. My school set up on a hill, and I guess he followed me to school and he went across the bridge and a car hit him and killed him. They come and told me about it and I really didn’t believe it. And until I went out there and I went and told my daddy and he went out and got them and we took him and buried him in the front yard. And we were playing on some…Friends of mine in a house at my uncle’s house and we were jumping up and down like kids do and I fell and hit the corner of a table on my head. But the school there was nice, it was up on a hill. I walked to school all first second and third grade. Got a railroad track going to school and it was not probably two miles. It's a funny thing to remember your first, second, and third grade teachers. After that, you don't remember any teachers at all; I don't. But I guess that's how perceptive you are seven or eight years old; how fast your mind is. I can remember that. And my fifth and sixth grade teachers, I can't remember their names. MM: Interesting. Did you have brothers or sisters? RH: Yeah, one brother and one sister. My sister was born after I had already left home. There's about 19 years difference between me and her. And my brother; he's five years younger than me. MM: So you are the oldest? RH: Yes I was the oldest. And after – the coal mines started shutting down when I was about in the sixth grade, when I was about 11 or 12 years old. So they were letting go, a lot of layoffs. So my daddy went in the Air Force. He went in the Air Force. MM: Oh really, how old was your daddy then? Do you remember? RH: Well, he was 19 when I was born. 19, 20, about 30 I guess, 31. MM: So he was still young enough? RH: Yeah. And he joined the Air Force. And so we had to go to basic training naturally. And so he went to training and we stayed with my grandma and grandpa. By that time my grandfather had bought three homes in a little place called Rift. R-I-F-T, Rift. And they bought 3 three homes there and they lived in one and rented the other two out. So we stayed with them until my daddy got orders for his duty station which was in Alaska. MM: Wow? So y'all moved to Alaska? RH: We moved to Alaska, yeah. We took, me and my mother and my brother we took a bus, Greyhound bus all the way from West Virginia to Seattle, Washington. All the way across country. And in Seattle, Washington we got on the boat. And took the ship up to Juneau, Alaska. And they gave us a bus down to Anchorage. Allison Air Force Base. Elmendorf. There are two of them up there. So we stayed there for two years. MM: So what was it like? What do you remember about Alaska? RH: I remember loving it. It was cold, but it was a different kind a cold, it was a dry cold. It can be 40 below zero and you won't – it was cold, but it wasn't freezing where you had the humidity. And it was I remember it was kind of like trying to make a snowball out of Tide, it was so powdery. The snow's not wet like it was around here. But would it pack up. And I remember Danny had to use a headboard heater in his car to keep the water from freezing.. But I remember I like the hunting and fishing up there. Really nice. The schools were nice. That's where I took my driver’s ed in 1957. It was up there. MM: Okay, let's go back to your childhood a little bit. You talked about your dad and what he did. What kind of a father was he? Did you grow up in a strict household? RH: He was an excellent father. Of course, he didn't have time to be the kind of father that people think you should be, you know take the kids to baseball games, teach them all this stuff. He worked all the time. He was a coal miner. He had to make a living, and my mother…But he was a good father up until the time he went into the military. As far as I can remember my father might have taken a drink or so back when he was younger, far as I can remember back. As far as him being violent or something like that, no. He was a good father. And my mother she was a good mother. She was a very protective mother. My grandmother my grandparents they were the same way. I was the oldest and the first grandson of the family. My daddy had 11 brothers and one sister. It was it was a big family, a big family. MM: What did your mother do as a homemaker? What kind of chores do you remember her doing? RH: The house. The house had to be spotless. I mean that's what I remember about my mother the house we lived in, it was always spotless. There was never anything out of place. Mother was an excellent cook. And she was just a good mother all the way around. MM: Tell me about the early chores you remember having to do and kind of your work history as a child and teenager. RH: I can't remember anything that was really put on me to do. I don't remember why but I remember I like to help my mother. I’d do the dishes. I’d help her clean the house. And she 4 taught me how to cook. And stuff like that, and my daddy, like I say never had time to teach me nothing. I remember playing marbles. Out in the yard it was all dirt, our yard was all dirt, we had no grass. And I remember riding the sleds down but as far as chores go no about the only chores I can remember really having to do was more or less keeping my room clean and helping mother. MM: Did you say your grandparents had a garden and hogs and stuff. Did you help? RH: They always had a garden a pretty good size garden. Because my grandfather owned quite a bit of land. As I say he was the sheriff of Macdale County and so his brother, my uncle let my great uncle he always worked the garden always. And they raise corn, peas, cucumbers, tomatoes MM: So you got to eat from that garden? RH: Oh yeah in the summertime because grandma canned a lot. She used to can stuff we ate during the winter. And smoked meat and I can remember grandpa smoking meat in the smokehouse. And we kill a pig and we’d take it out and hang the hams all up and smoke them. And then go in there with a knife and cut you a slab of it off. Back then we had two smoke houses. And so we ate; we ate good. We always had chickens, always had eggs.. So you were a lot better off than a lot of your coalminer – RH: Yeah, because we were family. We were up big family. And the family took care of each other. I mean we had little squabbles and stop. My grandmother was Indian. A certain amount. My great-grandmother what's full-blooded Cherokee.. My grandmother you could tell it from her temper. She could be just as nice but if you tried to cross her or do something she thought you shouldn't be doing you heard about it. MM: Do you remember the story of how you and wasn't your great-grandmother that was full-blooded— RH: Yeah, my great-grandmother. MM: Do you remember the story of how they met RH: No there's not too much about my grandfather back that I can remember. When I was born I had three grandfathers. In grandma's and a great-grandfather and my grandfather on my mother side was a Grindstaff, a German, and my grandfather my mother's father was Irish and blank, but as far as going back to my great-grandmother I see pictures of her. I saw pictures of her and you could tell, lifecare, but I never matter MM: How did you think your parents thought about work? Your mother and father. Sort of their philosophy of work. How they tried to teach you about work. What did they think about work? 5 RH: They always taught me if you want something you got to work for it. Nobody owes you nothing all my families hard-working people. All of them.. They never took anything from anybody. None of them were ever in jail. There just good hard-working people. I mean there was never any bad apples I guess you would call them. As far as I can remember in my family. I had uncles killed in mind explosions. I had to kill in mine explosions. My grandfather, my mother's father, died of black lung. Black lung he was a coalminer. They were coal miners. No, my whole family was just hard-working people. When the coal mines closed up they all moved to Michigan, Ohio to find other jobs. Since then, I may have seen them once every five or six years. I haven’t seen any of them people for 20 years. MM: Really? Do you think there will ever be a reunion? RH: No. We've had a couple of reunions and the people from Michigan and places like that don't ever come. MM: No. Kind of lost touch. That's too bad. What was your first paying job? RH: When I was in high school, I worked with my uncle in a construction company. My mother's uncle; he's my great uncle. And he owned a construction company into Haswell, Virginia. They built homes. I worked for him for one summer. MM: And what was that like? RH: I loved it. It was hard work. MM: What did you do? RH: I helped him, construction work. I brang you know if somebody said, I need some nails, I they say we need some boards, I was a laborer a helper is what I done. But he was teaching me how to be a carpenter. And my mother's stepfather Mr. Miller he painted them. But after Summer's past, I went back to school and of course I didn't have a job when I was in school but then I got out of high school and that's another long story. MM: That's okay I want to hear about your work history. RH: But let's go back to my daddy. As far as I can remember he never drank anything ‘till he got in the military. When we all moved to Alaska, it seemed like things just completely changed around. He started drinking. In the military – he started-- he get not physically violent with mother but verbally. Started accusing her of things. And all that stuff. Me and my brother heard all this, and then he would use me and my brother as leverage to get mother to go by him liquor. Because she wouldn't do it. But then he'd start on me and my brother and she do it just to get them off us. And that went on over in Alaska and then we got transferred to Louisiana, down in Lake Charles, and it got worse, progressively got worse. And then we went through hurricane Audrey down there and then we got transferred back to Alaska, but Fairbanks this time. Then it really, really got – and then everything just went to pieces. He started drinking more and more 6 and he’d wake up where he didn’t go to work. And so finally, the military just finally—I guess they had enough of them, they put him out. Out of the Air Force. MM: Did he get a dishonorable discharge? RH: I don't know whether he got a dishonorable or general. I know it wasn't an honorable discharge, I know that ‘cause he was in the Navy during World War II and you got an honorable discharge out of the Navy. And then when things got really, really bad, he got put out, and we had to move back to West Virginia. So we moved in with my mother's mother and father. MM: And your father was there also? RH: Yeah, but it just got – my grandfather wouldn't put up with it. He was older and couldn't do nothing about it. I remember one time him and my mother got into it, and I ran to my uncle’s house, my mother's brother, the only brother she had, Uncle Clarence, and got him. And he came back and boy, he put a beating on daddy and they put him out of the house, he and my grandpa put him out of the house. And I don't know where he went after that. And I was just, well I guess, weeks away from graduating from high school. So I got out of high school and went straight in the Navy. To get away from that. MM: Why did you pick the Navy? RH: Well, I was going to go in the Air Force ‘cause my daddy went in the Air Force, but then my daddy talked me out of it. He told me that he wouldn’t sign the paper; I was 17, and I couldn't sign the paper. I couldn’t. If I wanted to, I’d had to wait until I was 18 to go in. So I said fine and I went in the Navy. MM: And what was that like? What was the Navy like? RH: The Navy? I enjoyed it. I enjoyed my military, you know. I had a good time; I seen a lot of things. I was on a ship most of the time for four years. And my duty was good; I had staff duty. I was a radio yeoman. Yeah, I went to Europe twice, and I was in Cuba during the blockade. MM: How did you like Cuba? RH: We didn't get to see much of Cuba; we seen Guantánamo Bay. That's about all we seen. We couldn't get out; we couldn’t leave the base. MM: Interesting, very interesting. You were in the Navy four years? Why did you get out? RH: In between, while I was in the Navy, I got married, which I shouldn't have ever done. My friend, Roy, and I wanted to do some traveling, but he got married. So I met Gail in Alaska. Her brother, his name was Chuck, me and him were friends, so I met her and went in the Navy and wrote her while she was in-- they lived in Fayetteville, North Carolina, ‘cause her daddy was 7 Army. And so I wrote her, and just started going down there, and visiting her, and just finally got married. I don't know why. But I had two good sons out of it. MM: So, how long were you married to Gail? RH: Oh, probably nine years. MM: So nine years, and then you guys got a divorce? RH: Then I met—me and her, I go to work, and come home and the kids would be nasty diapers, Ronnie Lee, and she’d be sitting there watching soap operas. MM: So she didn’t have a good work ethic? RH: No. She didn’t have one, and she was a registered nurse. She just didn't want to work. All she wanted to do was just sit there in the house, smoke cigarettes. And so finally, I just had my fill of it, so I left. And as time went on, we had Steven and Ronnie, and it got so she would go out to the bars and leave the kids in the car. so finally, I found out about all of this, and I took her to court, and got Ronnie Lee, and then finally got Steven. And that's when I met Jane. I met her at miniature golf in Fayetteville, putt-putt, and it was in ’72, yeah. And me and her started dating, and I married her, and she raised my two boys. And as far as they’re concerned, she's their mother. MM: How old were the boys when you and Jane got married? RH: Let's see, I think Ronnie Lee was about nine or 10 and Steven was five or six. MM: So she essentially raised them with you? RH: Yeah, she raised them. MM: So going back to after you got out of the Navy, what job did you get? RH: I went to work, after I got out of the Navy, for Cole Dairy, delivering milk door to door in Fort Bragg. That was a military base, Army base. And there were some strange women out there, believe me. (Laughter). You’ve heard the story about the milkman? MM: Yeah, it was all true, huh? RH: (Nods). Anyway, I worked there awhile, and then I went, as I said, things started going dad between me and Gail for a long time, so I left and went to Virginia, and went to work for Virginia Power and Light Company back there. Then I went to work for Caltech Industries and I worked up there for a while. MM: What did you do for Caltech industries and Virginia Power? 8 RH: We wound coils and then she came up there and stayed for a while, but it still wasn't working, so she left and went back to Fayetteville. And then I finally got tired of Virginia, so I left and moved to Southern Pines, North Carolina. And I worked for an iron company, making irons. They had a big company over there. And I buffed irons. The bottom of the iron, I re-shined. And I worked at a golf course there for a while, hooking up golf courses at night, carts at night, putting a charge on them. And then I moved back to Fayetteville, no I didn't, I went to work for Bright Hampton Marine Houses because I went to school for some horticulture. So I went to work for Bright Hampton for about two years. MM: And what did you do there? RH: Just helped in the greenhouse; we raised a lot of plants. And I would load them on the truck and take them around to florists consultant to florists. And I did that for a while. where I met Bert and Ralph Richardson. And Ralph was a pastor. And he was a preacher, but he worked for putt-putt golf. And so he got me on in the warehouse for putt-putt golf. And I worked there for years. I worked there from ’75 up to about—no, earlier than that. I went to work there in the 60s, probably ’68 or ’69, and I worked there all the way up to ’81. MM: Wow, that was a long time. RH: Yeah, I become warehouse manager there, and worked for Don Clayton, who was the original founder of putt-putt golf. And then we worked there – and then in ’81, me and Jane decided to start our own miniature golf, so we left that company, and moved to Jacksonville and bought a miniature golf place in Jacksonville, North Carolina. And opened it up; it did great. ‘Cause that's about the same time, we open that up, which was in ‘81, that videogames were starting to get popular. So we built a building, and put 25 big video games in it, in the building. And we had pizza, hot dogs, and of course, miniature golf, putt-putt. And it just took off. And we done really good. Bought a home in the country club. We paid cash for her Cadillac. MM: Wow; you did really well. RH: We did really well. Yeah. And then Ronnie and Steven graduated down there. Of course, when Steven graduated, he went straight into the Navy when he graduated. He didn’t want to go to college. I said, “Okay.” Ronnie Lee also. MM: Also went in the Navy? RH: Yeah, also went in the Navy, yeah. And of course, they both learned a trade that they know right now, that they are working with right now. MM: And what are they like as workers? What is their kind of work ethic? RH: Steven’s always been a good worker because they worked for us in the putt-putt also, the kids did. And Ronnie Lee has always needed somebody to push him. He was married twice. And none of that ever worked out. Moved to California. I don't know what went on out there; I didn't see him for about five or six years. But then he come back here, and he met this girl he's 9 married to now, and they had a baby, and I've just seen him switch all the way around. He completely changed. MM: For the better? RH: Yeah, but he got Danielle. If it wasn't for her, he wouldn't have nothing. He's just one of them kind of people. But that little baby made a world of difference in his life. And Steven has got-- he married a girl. And when me and Jane moved from Jacksonville up here in ’91, back then during the Iraqi war, the Marines left Jacksonville, so our business got really, really bad. We sold out. At that time I had a bar, but we sold all that and moved up to Hickory, where we live now. And I went into the bar business, which was a bad idea, but a good thing came out of it. Steven met Alice. At that time, Alice was running with a crowd that me and Jane didn't agree with. And we tried our best to break them up. But Steven wouldn’t have none of that. Anyway, he finally married her. They got married and had-- and at that time she had a girl, so Steven adopted her, and she lives in Florida and she's a schoolteacher. And they just had had my great-grandchild. MM: Congratulations. That’s great. RH: And then they had Danny and Stephanie. And Danny works the same places that he does right now. And Stephanie is in college. They were in Florida. Moved back up here. And they live in Greensboro now. MM: That’s great. How long were you in the bar business? RH: Long enough to get cut and fed up with it. Cut-- MM: Oh my goodness. Like with a bottle or something? RH: Yeah, a guy came up behind me with a knife. MM: Oh, good grief! RH: And I got hit with a beer bottle. MM: Oh my gosh, so how many years did you do that? RH: Oh, about a year and a half. MM: So a short time; you knew enough to get out. RH: Yeah, ‘cause me and Jane were having trouble over it. And finally she left, and she went to Connecticut. And so I finally got tired of the bar business and sold it. I went to work for a furniture company, a supervisor any furniture company. MM: So was that your last job, the furniture company? 10 RH: Yeah, it was the last job I had before I retired ‘cause Jane came back in 2000. And me and her got remarried. And she was a real hard-working person too. She's like Pat, she was a hard-working person always. So we opened up a restaurant business in Hickory, and I opened up a bar, which she didn't like it again. So when she came back, I sold the bar. Got rid of it. And she opened up that restaurant. She didn't like that ‘cause we couldn't find good help. So we kept it for about two years. Meanwhile, I was working at the furniture company full-time because I was a supervisor there, and so she was more or less stuck with the restaurant on her own. So finally, me and her decided to sell it, so we sold it. And she went back to school and become a manicurist. She always loved doing here and manicures and stuff like that. And she opened up her own shop. But I was still working at the furniture company. I worked there, all about 12 years. And then she got sick in 2009. She got lung cancer. And in 2009, I took an early retirement, because where I was working, people were taking an early retirement anyway because business was bad back then. So I took my early retirement; I took care of her until she died. And I met that one in there. MM: There you go. RH: That’s the best thing that's happened to me since then. MM: Was what is your favorite job, Ron? Of all your jobs? RH: I think putt-putt what is my favorite job. MM: Working for somebody else or having your own putt-putt? RH: Working for somebody else if I look back on it because being self-employed involves a whole lot of stress. Involves a whole lot of financial responsibilities and worries then you would have if you work for somebody else. You know you got employees to worry about. You got taxes to worry about. You got a whole lot more things to worry about. Even though you make good money, it's still a lot more stress. Yeah, I liked, I'd say I liked working for Don Clayton, was the best time I ever had because Don was a good man, and he took care of you. And if you needed something, he was the type of man that me and Jane bought a house in Fayetteville, and we had a housewarming party and of course, Don came over. In the house was hot. So he called me in his office the next morning, and he said—(getting emotional) he was this kind of man, he said, “I want you to go and have central air put in your house. MM: And he paid for it? RH: Mmm hmm. MM: Wow, what a guy, yeah, what a guy. RH: He was like a father to me; he really was. And Jane too. But he was a good man. An excellent, excellent man. 11 MM: Okay, my last question to you. Is do you notice anything different about people's attitudes towards work today as compared to yours and your family’s? RH: I just don't see people today having pride in the work they do or having pride in themselves because they take care of themselves. You know, they can go to work and come home at night and say, “I did this.” I see young people today; I see a bunch of people feel like they're privileged, that this country owes them something. And that the generation before them owes them something. It’s just totally different than when I was coming up, the way I was taught, the way I taught my kids. I was always taught if you want something, work for it; my kids were taught the same way. Chores to do when you come up, either cleaning the yard or cut the grass or whatever. I mean, they weren’t perfect kids, but they never got in no trouble. Neither one of them smoke; they don't drink. They go to church and they raised my grandkids the same way. Nowadays, I seen kids standing up and talking back to their parents, telling their parents, “No, I ain’t going to do this,” and, “I ain’t going to do that,” to me it's just wrong. Totally wrong. But parents have nobody to blame but themselves the way I look at it. MM: Is there anything else you would like to add? RH: Well, what I've had is ups and downs, I've had a lot of disappointments in my life, had a lot of things go on in my life that I would change, but I know I can go back and change them. I lost my brother in a gun accident which was my fault, but I live with it. And you try to see a kid that maybe you can say, “Well, look, if you keep following this road, this is what's going to happen, even though they’re going to look at you like you're stupid. But maybe one of them won’t. Maybe one of them will say, “Well, maybe that old man knows something I don’t.” And I try to help people as much as I can. I don't judge people. I don’t, as far as I can tell, I don't have any racist prejudice toward anybody. If they’re a hard-working people, then they earn my respect. But my mother is totally different. She's totally racist when it comes to the Blacks or any other—she calls them Americans. “What’s an American mother?” “White!” “Really, mother.” That’s just the way she is. That’s why I don’t take too many people around her, because I know how she is. MM: Was she always that way? RH: No, ‘cause my grandmother, her mother and daddy, were never that way. You know, they were good people and they would help. They didn’t care what color you were. If you were in needs, and they could help you, they would help you. And I don’t know where my mother got it from. She must have got it from – self-taught, I guess. She just growed to hate people. And sometimes it's not even Blacks; sometimes it's whites. Sometimes it’s anybody. She’s just not a sociable person. I think my daddy had a lot to do with it, with her attitude towards things. ‘Cause after they divorce, and she had to work. She worked two jobs, probably all her life from the time she was probably 35 to 40 all the way up to about six years ago, and she's 94 now. MM: Wow, that's a long time. RH: And she always worked hard. And my sister is one of them privileged people. She thinks mother owes her everything. And she steals from my mother. She used to; she can't no more 12 because I put a stop to all that. But she's no help to me at all. You know, taking care of mother. And she was raised by my grandmother because my mother was working all the time. So my grandmother more or less raised her. And she always got anything and everything she wanted. And I'm glad I wasn't raised that way. MM: Looks like there is a big difference in the way you were raised. If you get everything you want, or if you have to work for what you get, it turns out a different kind of person. Interesting. RH: --one day. She taught her kids the same way. the kids are exact the same way as her. MM: Well, thank you very much, Ron. This has been very interesting, and I really appreciate it.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Ronald Hicks discusses growing up in West Virginia and Alaska, and how work ethics have changed since he was young. He talks about his family, different work experiences from owning a putt putt company to being in the Navy, and the different places that he has lived. This interview was conducted to supplement the traveling Smithsonian Institution exhibit “The Way We Worked,” which was hosted by WCU’s Mountain Heritage Center during the fall 2018 semester.

-