Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (26)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- 1700s (1)

- 1860s (1)

- 1890s (1)

- 1900s (2)

- 1920s (2)

- 1930s (5)

- 1940s (12)

- 1950s (19)

- 1960s (35)

- 1970s (31)

- 1980s (16)

- 1990s (10)

- 2000s (20)

- 2010s (24)

- 2020s (4)

- 1600s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 1910s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (15)

- Asheville (N.C.) (11)

- Avery County (N.C.) (1)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (55)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (17)

- Clay County (N.C.) (2)

- Graham County (N.C.) (15)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (40)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (5)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (131)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (1)

- Macon County (N.C.) (17)

- Madison County (N.C.) (4)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (1)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (5)

- Polk County (N.C.) (3)

- Qualla Boundary (6)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (1)

- Swain County (N.C.) (30)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (1)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (3)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Interviews (314)

- Manuscripts (documents) (3)

- Personal Narratives (8)

- Photographs (4)

- Sound Recordings (308)

- Transcripts (216)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Bibliographies (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newsletters (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Publications (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- African Americans (97)

- Artisans (5)

- Cherokee pottery (1)

- Cherokee women (1)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (4)

- Education (3)

- Floods (13)

- Folk music (3)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Hunting (1)

- Mines and mineral resources (2)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (2)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (2)

- Storytelling (3)

- World War, 1939-1945 (3)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Sound (308)

- StillImage (4)

- Text (219)

- MovingImage (0)

Interview with Calvin Carter

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

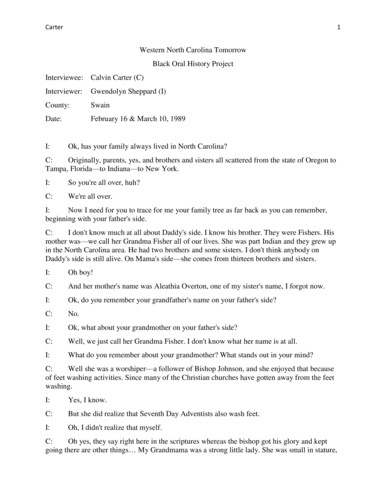

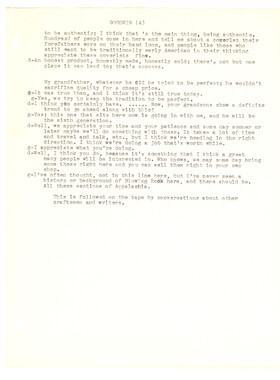

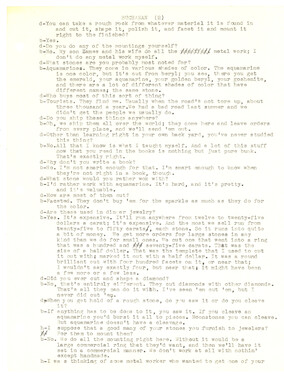

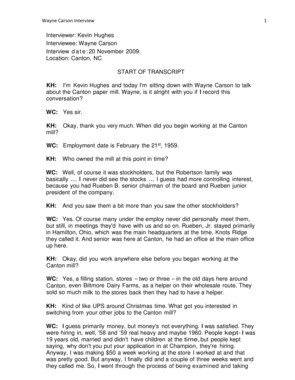

Carter 1 Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project Interviewee: Calvin Carter (C) Interviewer: Gwendolyn Sheppard (I) County: Swain Date: February 16 & March 10, 1989 I: Ok, has your family always lived in North Carolina? C: Originally, parents, yes, and brothers and sisters all scattered from the state of Oregon to Tampa, Florida—to Indiana—to New York. I: So you're all over, huh? C: We're all over. I: Now I need for you to trace for me your family tree as far back as you can remember, beginning with your father's side. C: I don't know much at all about Daddy's side. I know his brother. They were Fishers. His mother was—we call her Grandma Fisher all of our lives. She was part Indian and they grew up in the North Carolina area. He had two brothers and some sisters. I don't think anybody on Daddy's side is still alive. On Mama's side—she comes from thirteen brothers and sisters. I: Oh boy! C: And her mother's name was Aleathia Overton, one of my sister's name, I forgot now. I: Ok, do you remember your grandfather's name on your father's side? C: No. I: Ok, what about your grandmother on your father's side? C: Well, we just call her Grandma Fisher. I don't know what her name is at all. I: What do you remember about your grandmother? What stands out in your mind? C: Well she was a worshiper—a follower of Bishop Johnson, and she enjoyed that because of feet washing activities. Since many of the Christian churches have gotten away from the feet washing. I: Yes, I know. C: But she did realize that Seventh Day Adventists also wash feet. I: Oh, I didn't realize that myself. C: Oh yes, they say right here in the scriptures whereas the bishop got his glory and kept going there are other things… My Grandmama was a strong little lady. She was small in stature, Carter 2 she was strong, and she walked all the time until she became ill and she must have died in the late sixties because Daddy was murdered and she was alive in that time. So she and her daughter stayed together in Wilson. Her daughter Aunt Addie was a insurance lady. That's about all I remember about Grandma. She's very sketchy. She didn't live with us. I: Did you see her very often as a child? C: Not that much because she didn't live with us. In Wilson we lived geographically ten miles apart and that can be a long distance. So we didn't really… We see her once in a while and that's all. I: Did she ever tell you anything about her parents or any of the other relatives? C: I know very little. Now on Mama's side, Grandma stayed with us during the summer months and she would go and visit her other children in Philadelphia during the winter months. So we knew a lot more about Grandma. I: Ok, tell me about Grandma Aleathia. C: That one had thirteen sons and daughters. She outlived her husband and nine of her children. I think she was 97 when she died, and of those 97 years, she had only been bedridden for four. She fell and broke her hip when she was about 93 years old and just couldn't recover at that late age. And the thing about Grandmama that was so good other than being my constant protector—I’m number twelve of thirteen brothers and sisters. I: Oh, so you're one of the babies! C: One of the babies. So I was there and Grandmama was there and she taught me about sewing. She could make quilts, blouses, skirts and pants. And if a button came off Grandmama was there to take care of this. Mama didn't have anything to worry about when it come to that. And cooking, rolls, baking—Oh Lord… I: So did she teach you how to cook and sew? C: I caught many of my habits after Grandma although in Wilson I still had four of my sisters home when I grew up in the house and two others out of the house, but in the same location. With all the sisters around we had plenty of female companions to teach us these housekeeping skills since the high schools were prejudiced against guys going into home economics. So this Grandmama was the anchor of the family. That's life. She many a times sat us down. She was very fair complexion—long hair—high cheek bones. I: Is she the one you said was part Indian? C: Right. Well, she carne about through some freed persons. In North Carolina, in Edenton, North Carolina where she come from—her daddy was a Dutchman or something like that, and they were free blacks. Grandmama Fisher had ties of slavery on her side, but on Mama's side Grandma Aleathia, there was no slavery at all attached from where we could understand. One of my nieces has started a history tree, a family tree, and I don't know how far she got before she stopped. But that part of the clan was never slaves in Carolina. So being fair skinned and tall in stature and she has some Indian features but she was the anchor of the family. As I said they owned property in Edenton, and it seems like a lot of blacks in that part of the state owned property in the Overton’s family and the Fisher's family, but some reason they sold it out—sold Carter 3 out—there are still remnants of the family in Edenton, North Carolina. Being number twelve, I was too far away from all of these cousins. We had too many. I: I can imagine with the amount of children and then cousins and all. C: And nephews and they got babies of their own. I: I guess the Carter Family Reunion is really a reunion. C: It's a clan, it really is. I recall at Daddy's funeral, we were in church, and on the way out, and there were people still in the processional line in their cars trying to get to the church. That was one of the longest. Maybe at the age of eleven you see everything as big, but to me the people still coming in as we were going out, and the service was over. But that was good. Grandmama was the anchor of the family. They tell me she couldn't read, but she could count money. I: Oh, so she was good with numbers. C: She was excellent with money, and she always hid candy and always had it ready when you needed it. I: Sounds like a good grandma! C: And she chastise you—buddy when she got on to you—she got you. But Mama—after a while she would call Mama off. "That's enough Frank, that's enough.” Boy I was happy about that "that's enough" sound. I: You must have been a mischievous little boy? C: Very mischievous, but I was Grandma's favorite. I: Now we were talking about Grandma Aleathia. When you were little do you recall her ever sitting you down and talking about her parents and all the relatives? C: I don't remember any names, but she had the grace about herself of being a lady. I cannot remember to this day of ever seeing her wearing pants. I: Really! C: No. And yet I don't know what denomination she attended, if she went to church. I don't recall her going to church with us on Sunday. I used to go to the Methodist church. In our house we had to go to some church. It didn't care which one but you had to go somewhere and have God in you. And I remember her always praying two times a day—in morning and at night. And we had a wooden floor, and that lady knelt on the floor every day the Lord gave her breath. So she sat us down, and she told us about right and wrong—me and my brother—my brother Charles and I. He's the baby, the thirteenth. So we were a mischievous bunch that she had to deal with—that she had to raise. She was our doctor, our medicine man, our everything, and she would just tell us, "You're not doing right." She was encouraging me to better because I didn't like school. I don't particularly—well most of my peers went to kindergarten church schools. So when I hit the first grade, I was already behind in some of the skills since they had already learned. I didn't like to go to school. But Grandmama was always there. But those culinary arts things that she told us to be sufficient for yourself. Those are the things that I can always put Carter 4 Grandmama with. I don't ever see her worrying about anything. She had thirteen sons and daughters. She knew where she was going to be, what time of the year she was going places; she rode the buses, she rode the trains by herself from Philadelphia to North Carolina, and there was no inner fear in her mind. This lady was unique in herself. She was a beautiful person. I: Sounds like a great lady. Ok, what did your grandparents do for a living? C: They owned property in Edenton. The store or anything like that, property. I: Did they rent this property out? I don't know if he owned but I know they owned C: When they came to Wilson, there was six of us born in Wilson. The other ones were born in Edenton. So Barbara—I don't know. I'm 41—about two years apart. So somebody up there about 48 years old was born in Wilson. So I think they sold the property cause her granddaddy must have died and she came along with her daughter to Wilson, and the other daughters went to Philadelphia. I don't know how that worked out. I: Can you think of anything else you would like to tell me about your grandparents? C: Well both of them, Grandma Fisher and Grandma Aleathia, had a pride about themselves and about womanhood never erased. I like that. They made people respect them. I: Ok, now let's talk about your parents. C: Let's take my dad. I: Ok. C: Cause I don't know much about Daddy at all. Daddy was about 5’10", 190 pounds maybe, muscular, high cheek bone, my complexion, brown maybe tan, sharp dresser. He used to work on the railroad. Cause that's how he and Mama got up with each other. He was working on the railroad, and the railroad came behind their house in Edenton and she brought him some water and all this stuff and a courtship developed. I: Love at first sight. C: Love at first sight. I remember about Daddy. He was a very quiet man. Some fathers raised their voice, curse. Boy, when they are home you know they are home. Daddy could be home, and if you didn't smell his cigar or his pipe you may not have known he was home. He would get a paper, and he would sit down and he would be quiet. I don't recall too many conversations that he and I ever had together. The main conversation I had was about a bicycle. He bought me a bicycle for Christmas, and when he was working at the warehouse he used to ride it to work, and I would walk to school that day. And other times when I was in fifth grade I started riding my bicycle to school. So Daddy and I shared bicycles, but I had to prove to him that I was ready for that. He had a old bicycle on the back porch steps he never used, and I took it out, I got it ready, and I rode it and I repaired it, and then he saw that I was able to take care of something. When Christmas came I got a brand new bicycle. I: Great! Was that your favorite Christmas? C: That was my favorite. That's right. I got that bicycle and I kept that bicycle a long time. After I got out of Winston Salem State, four years of college, I still had it when I moved to Carter 5 Yonkers, New York, I still had it. And then one of my nephews asked to borrow it while he was working at night and didn't want to walk. "Sure you can borrow it, but take care of it cause I'm going to pass it down,” was my reply. I don't know where it is now. I: That's a shame. What did your dad do for a living? C: He was a chauffeur, and he worked in a tobacco market. Now as a chauffeur, I don't know how he did it, but he drove. Cause we never owned a car in our family, but he got his license and he drove this white person around in the off seasons. We didn't live on the farm. He worked the tobacco markets. Wilson was the loose-leaf tobacco center of the world at that time. Boy, we had more tobacco coming through there than anything else. We were the capital center of the world for exporting tobacco, cane, and cigarettes. So he would work there, and when the tobacco markets closed he would become a chauffeur. That's why I didn’t see much of him because he was off driving. Gone somewhere—the only time I saw Daddy was on Sundays and Saturday he would give Mama money for groceries. He would go. Sunday he'd be home reading the paper. I don't ever remember any major conversation that he and I ever had. I: He was that quiet, huh? C: That quiet a dude. I respected him. I know he whipped me one time. Mama did most of the beating in the family. Daddy would talk to you, whip you, talk to you, whip you, talk to you, so everybody preferred Mama to go ahead and beat you and get it out of the way. I opened my sister's letter. I don't know why, I couldn't read no way, but I opened it and she told Daddy and he whipped me real good. I don't remember him ever whipping me again. I know I never opened anybody else's mail. I: That's one whipping you remember, huh. C: I remember that. I always felt he liked my younger brother more than me. I think I was somewhat jealous of him. Because Charles had the long pretty hair, named after Ezra Charles, the prize fighter. Ezra Charles was a champion and this guy's too cute to be a fighter so he just knew he was gonna be a lover. He thought he was a lover, too. So he and Daddy—there was a picture—one Christmas he was sitting on Daddy's lap holding a football and Daddy's sitting there with a cigar. I saw that picture and I asked myself, where was I? Why wasn't I sitting on Daddy's lap on the other knee? But I got over it, and if—I don't know much about Daddy at all. Charles know even less, but I felt that he preferred Charles. I do know that one time Daddy and Mama—Mama was telling us how Daddy broke her from following him. She didn't know where he was going always either. So Mama being inquisitive, decided to follow him. He left the house, she left the house. Daddy walked her all over Wilson. He walked her up a hill. She got to the house and I don't know what the conversation was. I have never seen my parents argue. Never. Daddy wouldn't talk. Mama would be fussing. She'll fuss at the kids, she'll fuss at this, she'll do that. Daddy would say, "Eva, that's enough." That conversation ended. But I've never seen them fussing, never. They shared the same bed, they shared the same house, they shared the same love, and I could never see—I never saw them argue. He outdone me. I: Did you say he was murdered? C: He was walking to work in 1957 I think it was. He was walking to work and a car came off the road and hit him and drug him for about a quarter of a mile, and in that dragging time, the Carter 6 car went off the road, back on the road, off the road, back on the road, stop, pulled my daddy's body off into a ditch and drove off. I: Did you ever find out who did it? C: At that time, the only good nigger was a dead nigger, and we knew it. My mama always thought that in his chauffeuring, that he may have heard something, or saw something that somebody didn't want him to know. Mama died with that thought in her mind. But soon after he died, some of the people he used to chauffeur died of natural causes. So I mean they appeared to be in good health and all of a sudden, left and right, people started dying. That he knew. So Mama had her own superstitions and she felt that the police account for Northerner… Let’s see, 301 runs from Florida to New York and through Wilson, so…I don't like to reminisce sometimes, it's too hard. The police told us that it was a Northerner because of the glass they dug out of Daddy's body came from a car that was not normally part of the environment that we lived. Therefore, their tracing of it, which they only did for one week. To my knowledge the police only looked for one week for the murderers of my Daddy. Now somebody told me that Grandma Fisher, Daddy's mother, had gone and told them to stop looking. I don't know if that's true or not, but they only looked for one week. I know that's true. The person was never brought to justice because we were black. If we had been white, they would still have been looking, and somebody would have been found. I: Was that the worst thing that you recall happening to your family because you were black? C: Well basically, yes. See the Carter family will be thirteen. We're smart. I have some of the foxiest sisters in Wilson. That's right. This is something I grew up with. They were beautiful people. My mother was a beautiful lady. Alright, somewhat tall, heavy set, and she just bore beautiful kids. I used to feel I was the black sheep of the family because I didn't have that long pretty hair. I had those little bee-bee shots and all that stuff. I always kept it cut close, always. And like I said, Charles, he had that long pretty hair see. Fairer complexion than mine. So I was the black sheep. And my sister Madeline, we called her Rabbit, she thought she was the black sheep of the family, but we were smart individuals. Most of us had come through the same high school and elementary school so we knew that Carters could read, write, and do arithmetic and there was just some smart people that didn't have much. We were always clean. To the best of my knowledge, we upheld the family reputation of being decent people. And people didn't mess with us. We weren't fighters. You know I mean nine sisters, my brother in Korea, the other brother when I was in elementary school he graduated from high school in 1954. I didn't know nothing about him. My two oldest brothers I didn't know nothing about. Anyway, so that was probably the worst thing that ever happened to us. We're a close-knit family and now nobody had ever died in our family. Somebody was taken away from us and it was taken away. It's not natural. It's taken away! That was hard. Yeah, that was the hardest thing I experienced in the family until I got to be a senior in high school and I thought the next hardest thing would have been my impregnating this young lady that I was dating. Because to my knowledge none of my brothers would never have done anything like that. To my knowledge, my father had never fathered a child out of wedlock, to my knowledge. And none of my brothers and sisters have ever told me of anything like that and nobody has ever claimed. So I thought here the black sheep again. Now I let him down. If he had been alive, I would have let him down. But Mama was strong, and Mama says "What you gonna do?" I say, "Well, I'm going to school because I Carter 7 don't want to go to Vietnam and I got to get a job and I need a education." Now we're drawing social security and I couldn't get married. If you get married while on social security it stops. I: Oh, I didn't realize that. C: That's right. Conditions from as long as you're in school-high school, or higher education and not married until you're twenty-two, you can draw. So I said that once the baby is born I'll be in college and all this stuff and I would take care of the child with my social security money. Mama didn't have any qualms with that because she knew I was sincere about what I was saying and that's what I did for the first three years of the guy's life. We took care of him with social security. So those were the two blackest times I think in my family recall. Daddy's murder and my having a child. Later I heard that my oldest brother had preceded me. I: So you weren't the black sheep. C: I was not the black sheep in that form anyway. He had preceded me in a lot of things. I: Let's talk about your mother. C: Ok. Well Mrs. Eva Overton Carter, queen of the family. It was—let's see, James would be sixteen years old this year, this month. So sixteen years ago, May 23, Mama died and the doctor says it was a blood clot. It's something broken loose by having so many kids. I was going home for my birthday to bring James home because she had seen them up in New York in February and I was going down for me--uh, high school reunion and birthday time and that was my birthday present-Mama dying. Ok. Eva Overton Carter. I called her the queen of the family because nobody bucked that lady. You may not like what she says, you may not like what she did, but it would never come out of your mouth. Maybe down the road, in a tree a mile away from the house, you can let it out but not at 409 E. Nash Street. You would not do it then. She knew she was the queen of the house. She knew she had the support of her husband, because the times that Daddy beat me and he got anybody, if she say "Daddy"—she called him William—“he been bad and I'm tired of it and you deal with him", he dealt with it; I guarantee you. She didn't say that too many times because she enjoyed it sometimes. I have some of the fondest memories of my Mom because we talked. She knew I needed help. I was eleven when Daddy died—got killed. Growing into manhood—my childhood stopped when he died, Wilson is a seasonal town. We had to pull tobacco, crop tobacco. That was the main way that we could make some money. Picking cotton, I had some sisters who can pick cotton, they could pick hundreds, three and four hundreds. And we are talking about 3.50 here a hundred now—$3.50 a hundred pounds! My sister would come home maybe with five, ten, fifteen dollars from a day of picking cotton. I would come home with maybe twenty-five or thirty-cents. Cause I never would get in the hundred and the man that we picked cotton for would buy you your lunch and all that stuff. He'd deduct that and there weren't nothing left. So he said, "I see you here tomorrow". I said, "Yo." Mother. I used to call her Mama. I don't ever, ever remember calling her Eva or Daddy, William. It was Mama and Daddy. I said, "Mama, I never bucked you gal." And I could talk to her like that because she was my friend. I said, "But when it's time to pick cotton, don't wake me up". I said, "Mama, I just don't have it, I don't have it." We used to have to get up at three o'clock in the morning to catch that cotton truck, get to the field, and as the moon was going down or the sun was coming up, we would be in the field picking cotton because the cotton was heaviest when it was wet. So you do all the picking while it was wet, while the dew was on it in the dark. Snakes, bugs, all sorts of that, I just didn't have the right motivation. No. No way. Mama saw Carter 8 that I was for real so she didn't force that on me. But I turned into a man when I was eleven, doing a man's job for a man's wages, and that's when Daddy was killed. So Mama saw I needed help and as a friend she told me that "You got to love everybody. You can't go around hating white people because all white people didn't do this to your daddy. All white people are not bad. You have to remember that we are Carters". Plus I like to cook, see. And Mama liked to eat. Yes, Lord she liked to eat. And could sing—oh. I: Is that where you got your musical talent? C: It came from Mama. I never heard Daddy sing a note in my life, but Mama was always singing. And my other sisters, the same thing. We never owned a piano or instrument of any nature. I understand my brother could blow the trumpet-Bill. But I never heard, or never saw it either. But Mama and I, we were friends. We could talk. We talked about growing up. She often kept at me about my attitude. I was a mean little boy. I was nice, but I was mean too. If you messed with me I'd fight you. If you don't mess with me, I'd be your friend. But if you mess with me I'm gonna fight you. I: I see you have that mean streak in you. C: I have. I have. I: Mothers know. C: Amen. It either came on her side or Daddy. It came from one of them or both of them. Cause I was a mean person, but I knew where to be mean and when to be mean, you see. I'd go to church. I'm a church-going boy, but you get out there on the streets and do wrong, I'll shoot it. Some of the times we had with Mama, she liked to tease my sisters. I had three sisters in college at the same time when I was coming through high school. I: How did your mother manage that? C: It was hard. My social security money, Charles's social security money, her social security money went to school. My sisters in school got scholarships. Once they got there, they didn't sit on themselves. They did good. Anyway, one of the sisters would come home, Clementine. And Mama would just talk about their old ugly boyfriends. Mama would get on Clem and it would just make her cry. I said, "Why'd you do that?" It's fun! Mama said it was fun to get them. Now I don't know why Clem was just the one that she would pick on. And Gloria Jean, my baby sister, would put too much lipstick on. Mama said, "Go in there and wash that mess off your mouth. Your mouth look a cow's behind!" Shoot it to ya, go ahead there Mama. No, Mama was a treasurer of her church. She was a Methodist. She had a lot of friends most of which were a part of her church. She was a part of the Eastern Star. Daddy was a Mason, Elk's one. All three of my other brothers are Masons. I'm the only one on the outside. And she worked in that export factory in Wilson as long as I knew that she worked. Now after I got out of school and Charles went into the Marines, Mama stopped working. She started living and enjoying her family. I: That's great. C: She visited the people in Ohio and stayed out there with my sister. It's hard to reminisce sometime and I didn't realize how hard it would be because I'm living in the present and most of my present of course have to be built upon the past. And I don't know. I miss them. Carter 9 I: Tell me about some of the happier moments. What was Christmas like for instance in your family? C: One of the biggest Christmases we ever had was when Daddy died. Daddy was murdered in December and it was before Christmas and it snowed that Christmas. So everybody made sure that everybody else had a good Christmas. We wanted to make sure that Pete and I was called Pete—and Charles and Gloria Jean and Clem make sure everybody had a big Christmas because Daddy was gone. We had good times at Christmas. The regular routine, Santa Claus get the cake and the coca cola and all that prepared, sneaking down the stairs trying to see, trying to catch anta Claus. Raised in a two-story house. I don't even recall ever having to share my bed with anybody. I: Oh, that wonderful. With as many children that were in your house! C: Thirteen, but you know they're gone by the time twelve get here. I: They were never all there at the same time, huh? C: Right. So, I'd share rooms. We was to sneak down. We had a lot of good times. The preacher would come on Sundays as usual and eat his big old meal and I'd get kicked under the table for reaching for the chicken before he did. Yes, typical southern raising. And I say typical at that time because everybody was doing it the same way. I: It was tradition, huh? C: Truly. A Sunday was the day that you ate the best. You dressed the best. Sunday meant something. You know you had to go to church, but if you go downtown to the movies or anything else, it was after the church. So, everybody in the community knew. Everybody in the community would participate one way or the other. But it's not like that anymore. I: Was this a close-knit community? C: I think so, because a section of town was sectioned off. Everything on the right-hand side of the railroad track was black. So the white folks lived on the left-hand side and the few whites that was on the right-hand side didn't realize they was supposed to be white. They was surrounded with all just black, understand? So, they had a personality conflict, and I never went to a integrated school. I graduated in 1965, and the school systems were still not integrated. They were still segregated. I don't know any outstanding thing that the family did because we were just peace-loving people, you know. We didn't do anything. We didn't have any racers. My sisters and brothers were outstanding in athletics. Levi was the captain of the football team. I played football and got a scholarship. That was the only way I could afford to go to college. Having helped Mama put three sisters in school, I knew what kind of burden that was on her. I was not going to do the same so I told her, "If I get a scholarship, I'll go to college." "If I don't get a scholarship, I'll join the Air Force." I got the scholarship. Amen, so I'll go to college. But going back to Mama—but we would talk about anything, anything I wanted to talk about she would talk about and we would laugh. We would have fun together. And when I see my sons and daughters now with their mother laughing and having fun I know that they are gonna look back like I am today and they're gonna remember those. We had a good time. We had a good time. So it's not that much in the Carter clan other than we would work. Nobody was in trouble with the law. Another thing, we had no smoking, no drinking in the family. It was not found. Daddy was Carter 10 the only person with a cigar or a pipe. Mama did not indulge in any kind--smokes or nothing. Neither did Grandmama. Grandmama would make some home-made wine. I suppose everybody would make that. I: Oh yeah, for church? C: For church, for seasoning and all that stuff. We never indulged in anything like that. I: You mentioned earlier that your, was it Grandma, was it Aleathia. You mentioned something about being a medicine man also. Did she delve any with medical herbs and that type of thing? C: Yeah, I had athlete's feet. I got it in swimming pools and swimming holes and it was itching so bad I said, "Mama, I need you girl—help me out." She put together a potion. I don't know. I know it had sardine oil in it, and I can't remember nothing else, and to this day I don't have athlete's feet in that particular place because of her potion. If you got sick—you know I played football—I'd come home with a injury or a sprain or something—it was Grandmama who came in ministered. Mama didn't know nothing, right. It was Grandmama who did that, alright. Mama nor Grandmama never went to a football game in their life. They didn't like violence. They knew I wanted to do it, and my brother Levi wanted to do it and they let us go. But any kind of headache, toothache, any kind of pain, Grandmama had the remedy. I: How did she learn this? C: I don't know. I: Was that something that maybe was handed down maybe from her mother? C: Truly, cause I don't know too much at all about her mother and father, but they picked those things up. And now she cured my athlete feet and I have the foot still to witness the fact that it's been cured. I: Now that's something hard to cure. C: I'll hear that. She could have marketed it. But she cured it. That's a fact. She was a doctor. She was everything. She's not supposed to know how to read either. I: So your family probably didn't have to go to the hospital very much; did you? C: I don't know of anybody that ever went to the hospital. I was born in the house. Charles was born in the house. All my brothers and sisters was born in the house. Dr. Cowan, that was his name, our family doctor. He would come to the house. We never went to no hospital. My mama. I told you before, never was sick. Out of thirteen sons and daughters, she saw all of them in the grave except four and never had been to the hospital a day in her life. I: Were blacks allowed to go to the hospital in Wilson? C: There was a black hospital. I: Oh, there was a black hospital. C: There was a black hospital and white hospital. They named it Mercy Hospital. They tell me you need a lot of mercy to get in that place, boy. Carter 11 I: Get in and get out alive! C: Amen. Right. There had to be some mercy from somewhere. But we never went into a hospital. That's… I: What historic event do you remember most in your life time? Like for instance the civil Rights Movement, or the Vietnam War… C: I like the civil rights because that was my age bracket. I came through that time. I was part of the protest marches. I took part in these things. In Wilson, the white only, the blacks here… time the 60s, I was in Winston Salem. I graduated in 1969 so dudes from A&T and the sit-in marches. I got mad because it didn't take place in Winston Salem first, alright. We came back to Wilson during my sophomore, junior year and we organized a voter registration. We got some blacks on the city commission and stuff that had not been there before. At least in a long time because it had a background where we found where blacks used to be in those positions, but some time lapsed in there and white took over. So I was very active in that. Also during the 60s when I was very militant also, see. Daddy had been murdered and I had not forgiven. I just kept up with some of the things I suppose. I really was discouraged when I learned that Malcom X had been murdered and I didn't have a chance to meet the man. I felt deprived because I never met Malcom X and I don't know nothing about Moslems. They're strange people. So even in blacks you know you have strange people that you don't want to mess with. But I didn't know his contribution because we're in the south and that's north. So the civil rights movement… was never jailed. We had peaceful demonstrations. But in my heart I wanted somebody to come up to me so I could just [get] them. I was mean. I: I think I would have been too if I had been grown during that time. Right now I regret not being able to remember any of this. I was a little kid at the time and it was just all a blur. I don't remember anything. C: Like I said, we were not a rich family by no certain imagination. People thought you had something because they never see you asking for nothing, all right. We ain't had nothing. So I didn't frequent any fast foods place. We didn't have fast foods place like McDonalds, but going to Woolworth and sitting down--we didn't do that. My family… didn't do that. The guys who got jobs during the year sweeping out the drug stores and stuff like that—well we thought of them as being queer, all right. We weren't going to clean up nobody's house and like that. Even a little bit of money—how much money is worth that much time. Well, I wouldn't do it. So we marched and we had confrontations with the clan and nobody got hurt but we were scheduling marches and they were scheduling marches. I: So, was this in Wilson? C: In Wilson. I didn't do nothing in Winston Salem. I came back—like I said, we got everything integrated during my time. And my peers there in the high school—we had the biggest graduation class. We had some folks that were up to date on things. We had winning of 4-A championship football, won the 4-A basketball the year before and they should have won it again in 65—should have but they cheated. They really did cheat. But my group of people were doers. That's the class that I came through. The young people, they are reaping the results of my labor, and that makes me angry because they don't appreciate nothing. I: They don't realize the struggle that you had to go through to get where you are today. Carter 12 C: No, they don't. As I said, we had a segregated school system. We, in my understanding, did not want integration. We wanted equality, but we didn't want integration. We loved our high school, and now it's a elementary school and so many of them have been closed down completely. We respected the teachers even though they had their flaws, all right. What we wanted was equality. If they got a new book at Fike, we wanted a new book at Dardin. I: That's only fair. C: That's all we thought. Now they built us a—the white administration built us a gymnasium, a new auditorium and a new cafeteria. But outside of the city limits, they built Fike a brand new high school, a brand new gym, their own stadium and didn't even have winning season. But they were white. Talking about bussing, we'd been bused all of our lives everywhere except us—the Carters. We lived a little bit past the city limits. City school buses would come past us everyday, couldn't ride it, couldn't ride it because it was too close to town. So in my time the 60s will always be the most memorable. In college was where I thank God he did allow me to go to college. I played football, and I joined the choir. That's where I met Dr. Dillard and he helped us to see parts of the world that I'd never seen. There was he and the Winston Salem State College Choir, I think it was in 1967 that we went overseas representing America in a black musical festival. We were the only blacks there. It was in a place called [Mayson], France—the eastern province there. We were there for a week and we toured Europe for the next twelve or thirteen days. It was about twenty-two days altogether that we stayed there. We went to France, went to Italy, went to Geneva, Switzerland. And there I had to rub shoulders with whites. I didn't like to rub shoulders with whites. I: Was that the first time you really had to interact with the whites? C: The first time I really had to and music is a universal language that break through racial barriers and that's where traveling from one event to the other, riding those trains that you see in James Bond movies—and they do stink—oh God, all over the place, have mercy. But I was sitting there beside a girl from East Germany, the one that's not communized and they was—she was telling me about their plights and at the musical festival we learned about the French Canadian problems with segregation and how they tried to compare it to our problems in America and I really started rubbing shoulders to get to know that—to believe that maybe Mama was right—that they are not all the same. So when I came back from Europe, I came back with a new determination to be better, to be a Christian. I involved myself—there was a Good News Singing. The Good News was a Christian movement for young people. They would go from activity to activity singing about Christ and brotherhood. The 60s were terrible days for white America too. They had to all of a sudden justify why these signs still remained for such a long time to their children. And their children didn't understand it either, you know. But we accepted it to be right because it is, but now we are questioning that and their own kids are questioning that so white America had some rough times in the 60s. Somebody ought to tell us the truth about that. They had some rough times. I met a Canadian over there and I said, "Well, Mama I met this girl and I want to bring her home" and Mama said, "Don't bring her here." The first time, the first time I'd ever known my mama to say not to bring somebody home. I: Did you think that was because she was Canadian? C: I thought it was because she was white, but there are black Canadians too over there. But I said, "What!" She said, "Don't bring her here." I said, "Why, didn't you always tell me to love Carter 13 everybody and treat everybody equal?" She said, "Yeah, but don't bring her here." And I let it lay right there and I never did bring her home either. But the 60s, I was in D.C.—I was in Baltimore, Maryland—oh no, no, no—we were in Wilmington, Delaware the day when Dr. King got shot. I: Oh, what do you remember about that day? C: We were giving a concert in Delaware and that intermission of the concert somebody brought us the news that Dr. King had just got shot. Now my wife was raised in Asheville. She don't really appreciate Dr. King. She didn't until lately because she didn't understand him. She didn't understand the purpose, the movement and how he got the notoriety that he had and I tried my association with her to just help her understand the type of pressure this man was under and yet did not succumb to violence. And I would have succumbed to violence. I: I would have too. I know myself. I would have been just like you. C: I would have been dead a long time ago. Anyway so after intermission they told us Dr. King was dead and we sang the second half and dedicated that to him. The next day the last concert stop was in Washington D.C. and they burned down almost half of Washington D.C. The day after King was dead, I forget the date, the year and all of that stuff—it has got to be 1967, 1968. But we had to cancel that concert because it was risky for the bus driver there and people were not going to come out and Dr. Dillard says no way. Get on the bus and go home. But we came back later and gave the concert. I was there in D.C. I saw a riot for the first time in my life, I saw people looting. I: In Delaware? C: No, in D.C. You see we gave a concert at night in Delaware?? I was thinking also it was in the 60s that President Kennedy got shot. I was sitting in high school that morning in a English class and I was sad. I had just done a Monroe Doctrine paper on the blockage of the missiles from Cuba and how we used that document to [interrupted by the telephone ringing. Could not make out last word], but I wanted to tell you about Kennedy. Kennedy meant something in the black community. Again, it was because of his stand for civil rights. He didn't have a chance to do nothing for civil rights, but he took a stand. It was Humphrey and the Johnson administration that got these things through. But Kennedy did take a stand, and we needed to see that. That's why he was loved—because he took a stand and that's all I can give to him. But Abraham Lincoln took a stand. It wasn't for black America. I: No, it wasn't. C: But the 60s definitely were the most challenging time. I got out of school and went back to home to work teaching business education in public schools and innovative ideas. But very hard to find an opening for business education teachers because people didn't leave their jobs. They did not leave. They stayed there and they worked until they had to retire. So I went north. Since I had family north and I was used to visiting north anyway and I got a job and got started on my life in New York. I do think we will have to come back. I: Ok, that's fine. [Part 2 of Interview – March 10, 1989] I: Mr. Carter, how long have you lived in Buncombe County? Carter 14 C: Ok, I think we go back as far as 1974, 73-74. I was married in 1971 and we lived in New York for over three years and came back to North Carolina [because] my employment was terminated and I was seeking job while on vacation. I: So it was work that brought you here? C: Yes. I: Ok. Since you’ve been here, have you noticed any cultural difference in the black community in this part of the state versus black communities in the eastern part of the state? C: N.C., I always say is very distinctively outlined. The east is very much different from the west. The blacks in the west when I first came here I didn’t know where they were. Riding the highways traveling from Winston-Salem to Asheville, I did rarely only saw one or two persons past Statesville of my racial content. I thought “oh where am I going?” So when I got to Asheville I saw even less. And this was on a Friday and normally we are out in the street. Of course I didn’t go to the area of Asheville where many people may have been but I still didn’t see them. In the east people to be more aware socially, politically, involved with community, schools. In the west, they seem to be more individualized, family-oriented, a little more church involvement. But the blacks are not as active up here and that accounts for what I believe the slowness of the project – integration, equal rights, employment, all qualified folks. The Founding Fathers of these little townships make sure they keep big business out and blacks limited. That’s my observation. I don’t know, when I was visiting Asheville, it was only because of a courtship so I didn’t really get around to talk to many people. But after living in Asheville, working for the people, many of the blacks in Asheville, the young people either graduated from high school and/or technical school. After securing their degree they know there is no opportunity for blacks—are next to nill—for progressive blacks. Seems like the only people who are getting ahead are those who are coming into the area either by federal or state or private employment. So there’s not a lot of hope for work and opportunities for a man. On the ladies’ side, I’m not sure how a lady. I: Tell me about your choir. C: That’s one of my happier moments. We are a small choral, we go as far as 23 maximum population. When I first came to Asheville as a married person and a member of the Seventh-Day Adventist Church, I found a lot of young people—13, 14, 15 years old—and those persons had nothing to do. You know we don’t go to socials, we don’t dance, there is no ball games or basketball games on Friday night. So I always loved music. Being a member of the university choir at Winston-Salem State University. Dr. Dillard instilled in us the love of music and to share with somebody else. When I came to Asheville and found all these young people w nothing to do, I said to my wife that we have to get a choir going so we had rehearsals three nights a week, two hours a night. She’s the pianist, I am the task master. I just keep everybody’s hearts afraid and trembling and minds motivated to the point where they can believe that they can do it. So we taught from Baroque, Bach, all the way down to Negro spirituals. The most enjoyable part of it, 90% of it is done acapella. So when you have a choir come up doing a Bach contada, the little bet [Lahana?] Christ laid def stop [inaudible]. When you’re doing the acapella, oh boy, a lot of folks sit up and take notice. I did it acapella because I needed my wife to sing the alto line but we learned the song with piano, of course but we performed it acapella and that started to get us into public notoriety. We performed at high schools, churches, on the radio. The music of the church Carter 15 is not swing gospel. Now I want you to understand there is a difference. We believe that through the senses God has given man powers to control some of the things that’s happened. Satan has taken advantage of some of the same senses and have overcome worship with style with pleasure-seeking, with everything else and confusing the minds of the people into making them believe this is it. When we came into the area in 1970, gospel was really getting off. And the big choirs, the James Cleveland choirs, they were just getting off. Asheville was loaded. So we didn’t want to do gospel, we wanted to maintain the Negro spiritual because it is there in the spirituals that black America finds its roots. So we did everything, we did Latin, German, English, of course and spirituals. The choir is still functioning—we sing twice a month at church. Now the church has grown and we got another choir so we don’t have to sing every Sabbath and we have a repertoire of I don’t know how many songs. We try not to do the same two songs every five or six months. So every Sabbath we have to sing two different songs. So that’s why I have to be the task master.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Calvin Carter is interviewed by Gwendolyn Sheppard on February 16 and March 10, 1989 as a part of the Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project. Carter discussed having Indian in his bloodline, how his parents met at the railroads, getting spanked as a child (preferring his mom to do it because she finished quicker), the importance of music to his life, and more.

-