Western Carolina University (21)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- George Masa Collection (137)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (3080)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (422)

- Horace Kephart (998)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (89)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (318)

- Picturing Appalachia (6617)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (153)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1463)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (91)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (2008)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (3032)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1945)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (195)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1680)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (556)

- Graham County (N.C.) (238)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (535)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3573)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4925)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (35)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (13)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (421)

- Madison County (N.C.) (216)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (135)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (982)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (78)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2185)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (86)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (193)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (3)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Digital Moving Image Formats (2)

- Drawings (visual Works) (185)

- Envelopes (115)

- Exhibitions (events) (1)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (823)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1070)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (6090)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Notebooks (8)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (194)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12977)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (6)

- Portraits (4568)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (181)

- Publications (documents) (2444)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Relief Prints (26)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (1)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (802)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (18)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (329)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (462)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1482)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (36)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1923)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (190)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (111)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (2012)

- Dams (108)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (63)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1198)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (47)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (122)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (9)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (72)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (174)

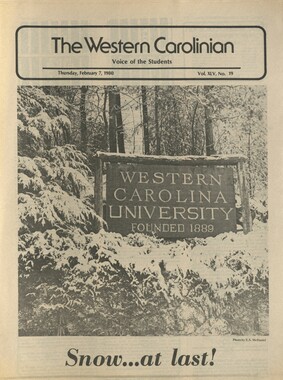

Western Carolinian Volume 68 Number 09

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

we news@email .wcu.edu By Joel Achenbach | The Washington Post. Ricin in the mail, airline flights canceled due to possible terror plots, something hideous called a prion lurking out there among the mad cows. A kid in Washington goes to school and leaves with a fatal gunshot wound. An I1-year-old girl in Florida is led away by a strange man and winds up murdered. These are just a few of the _ grim stories from the past few days, | some of them deeply disturbing and | tragic, others more in the category | of unnerving, or simply bewildering. They all drive home the feeling that life is a risky business. Just when you absorb one type of danger, someone invents a new one--SARS or avian flu or something enigmatic called nanotechnology, And yet even if the news offers constant affirmation to the paranoid, the hot political story involves weapons of mass destruction that increasingly appear to be nonexistent. A new government investigation will try to discover how we were almost all wrong about Iraq's arsenal, in the words of former CIA weapons hunter David Kay. Thus a fair question to ask around the water cooler is. how dangerous is our world? The risk analysts assure us that there are no simple answers here. The only certainty is that risk analysis is a booming industry, even though daily life for most people is measurably safer than it used to be. Life expectancy in the United States is nearing double what it was just a hundred. years ago, says David Ropeik, co-author of RISK!: A Practical Guide for Deciding What's Really Safe and Whats Really Dangerous in the World Around You. Just since 1960, infant mortality has gone down roughly a third. Polios gone. Measles largely gone. Smallpox gone, Ropeik says. The major scourges, major threats, are gone. But we dont care, because our job is not to think about what used to threaten us, our job as primates is to get to tomorrow. This is the evolutionary biology viewpoint: We may be genetically predisposed to find things to worry about. The idea is, were all in a competition for survival, and the vigilant are more likely to pass along their genes. The really sound sleepers sometimes get eaten by a lion. Robin Cantor, former president of the Society for Risk Analysis, puts American worries into perspective: At annual meetings of her society, scholars from developing countries often deliver papers about malnutrition, starvation, floods and disease. Scholars in more affluent countries focus on more exotic, low-probability threats. Rather than starvation, We're actually faced by the risk of obesity. she says. According to the Harvard Center for Risk Analysis, the annual odds of dying of heart disease are 1 in 397 (a crude figure, reached by dividing the population by the number of heart disease deaths; obviously the risk is far lower for young people). The odds of dying of cancer are 1 in S11. From a car accident: 1 in 6,745. From homicide: | in 15,440. From bioterrorism: 1 in 56,424,800. We obsess incredibly about things that are relatively minor, especially things that involve long polysyllabic names, says Gregg Easterbrook, author of The Progress Paradox: How Life Gets Better While People Feel Worse. The average person is much more likely to be killed by Twinkies than by weapons of mass destruction. There are discernible patterns to the way we analyze risk. We are particularly worried about risks involving things beyond our immediate control. The reason people dont fear Twinkies is that they feel fully in control of the fattening pastry. A person makes a risk-benefit analysis: might make you fat and eventually kill you, but in the meantime. tastes good. Another risk analysis truism: Man-made risks worry us more than natural ones. We're afraid of man-made radiation from nuclear power, from cell phones, from microwave ovens, from overhead power lines, more than the sun, says Ropeik. That solar radiation takes an estimated 9,800 lives a year from melanoma, and it causes 1.3 million cases of skia,cancer. Another of director of thatilary risks. West Nile vire Likewise, the ric ious pattern: New risks worry us more than old ones: James Hammitt. Center for Risk Analysis, says we've learned to live with the old 0 longer triggers many headlines. even though its still around. k on the Capitol this past we k may have been a big story, but if didnt generate a great deal of chatter on cable news talk shows, perhaps because this sort of thing has happened before, with anthrax. There are something like 40,000 people killed in motor vehicle accidents in the U.S. in a year, so 9/11 was something like one months road toll. But 9/11 had a much greater effect on our perception of risk, Hammitt says. He adds that this makes sense. Theres a historical database about car accidents, and thus thats a risk that can be understood and predicted. Never before in the history of mankind had a group taken over an airliner and used it as a missile. He says, What's different about terrorism is that theres an intelligent adversary thats really trying to get us, to harm us. Most of these other things are accidents. The new commission investigating the flawed intelligence about Iraqi weapons will have to re-analyze the earlier risk analysis, and sort through not only who knew what, but how credible each piece of information was, how plausible each scenario, how coherent the overall assessment. The commission may wonder: In looking so hard for WMD in Iraq, did intelligence agencies and the Bush administration fall victim to a believing is seeing phenomenon? We tend to find what we are predisposed to find. In psychology its called selective perception, says Ropeik. People also tend to underestimate risks. Some say that whats remarkable about humans is not their hand-wringing, but their complacency. Dennis Mileti, former head of the Natural Hazards Center at the University of Colorado, points out that countless San Franciscans live in homes built on top of debris from the catastrophic 1906 earthquake. Many failed to take basic precautions to secure their homes on their foundations prior to the Loma Prieta earthquake that caused billions of dollars in damage in 1989, he said. The human beings who lived in the Marina District atop the rubble of the 1906 earthquake didnt think that earthquakes happen in San Francisco, Mileti says. Human beings prefer believing that theyre safe, he argues. They delegate the problem of low-probability, high-consequence risks to their government. This seems to make senseuntil the government fails to keep lead out of the drinking water, or provide adequate safeguards against guns in schools, or keep the beef industry from putting downer cattle in the food supply. i A recent book argues that people should pay more attention to highly improbable but potentially ultra-catastrophic events, Martin Rees, an astronomer at Cambridge University, and author of Our Final Hour. a book with the shrieking subtitle A Scientist's Warning: How Terror, Error and Environmental Disaster Threaten Humankinds Future in This Centuryon Earth and Beyond, has argued that theres roughly a 50-50 chance that civilization will suffer some kind of massive calamity in the next century. | think that civilization is going to be vulnerable to various threats. he says. We're in general far too worried about small risks. A small risk, for example, would be potential carcinogens in food. A big risk would be a high-energy physics experiment gone awry. or terrorists manufacturing viruses, or even the resurgence of the threat of nuclear war. If people want to worry, he says, they should worry about the consequences of living in a more interconnected world where individuals are much more empowered by technology than they ever were in the past, where a small group or even an individual has access to the kind of power that was the prerogative of nation-states in previous centuries, Could a lone madman destroy the world? A James Bond villain sort of person? Rees answers, I think it is rather unlikely. Frankly we were hoping fora simple no. 2004 WASHINGTON POS WAAL AAD A ey AAA wy

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

The Western Carolinian is Western Carolina University's student-run newspaper. The paper was published as the Cullowhee Yodel from 1924 to 1931 before changing its name to The Western Carolinian in 1933.

-