Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (292)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2766)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1388)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (1794)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2569)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1923)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (161)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1672)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (233)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (519)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3524)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4694)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (25)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (12)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (212)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (981)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2115)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (84)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (184)

- Envelopes (73)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (815)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (5835)

- Newsletters (1285)

- Newspapers (2)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (6)

- Portraits (4533)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (151)

- Publications (documents) (2236)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (15)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Vitreographs (129)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (282)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1407)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1744)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (170)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (110)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (1830)

- Dams (107)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

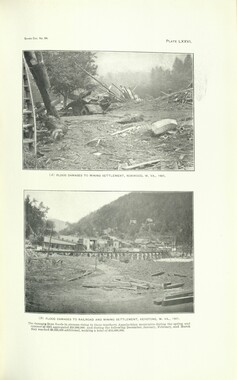

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1184)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (38)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (118)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (71)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (244)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

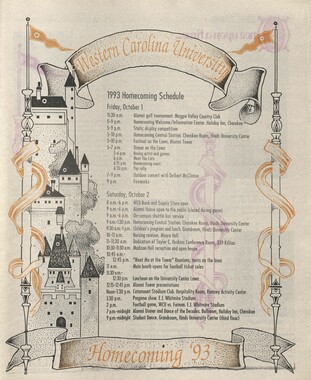

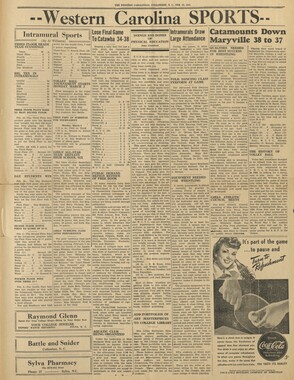

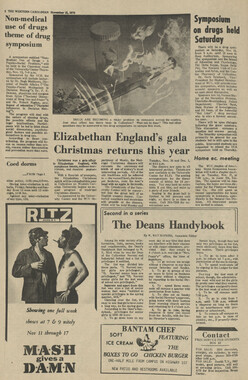

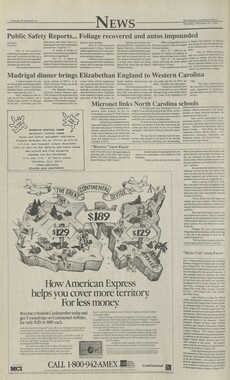

Western Carolinian Volume 67 Number 08

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

ewsma azine national news september 18-24, 2002 Special, Coverage: "America" part three Washington Post survey reveals ways we, as a nation, have changed Most Americans say 9/11 Affected Way They Think By Richard Morin and Claudia Deane I The Washington Post "Everything's changed" became the American mantra immediately after Sept. 11. "Nothing's changed," came the echo back a few months later. But although the imprint of Sept. 1 1 on the public is largely fading, a year later it remains clearly visible in many of the ways Americans think about their country, their leaders and themselves, according to a Washington Post survey. Public support for the military, which surged after the terrorist attacks, has not wavered in the intervening months and may even be increasing. Feelings of patriotism and national pride remain strong. Most surprising, America still basks in the rosy glow fueled by the heroism and everyday acts of selflessness and charitable giving that followed Sept. 11. About 6 in 10 Americans say that most of the time people ' 'try to be helpful," a view shared by fewer than half of those questioned in a survey conducted a year before the attacks. Americans are also significantly more likely to say that people are "fair" than they were before Sept. 11—an unexpected renewal of faith in humanity that has largely persisted over the past 12 months. "This crisis brought out the best in America—and made it better," said Amitai Etzioni, former president of the American Sociological Association and a professor at George Washington University. But the survey also found that many attitudes that changed dramatically in the immediate aftermath of Sept. 1 1 have largely changed back. President Bush's job approval rating, which soared to record heights, has lost much of that increase and continues a steady decline. The public's trust in the federal government doubled to its highest point in nearly four decades, but now is not much higher than it was two years ago. An overwhelming majority of Americans said the country was headed in the right direction in the days after the attack. Today, a small majority believe the country is "pretty seriously off on the wrong track," according to the poll. Even Americans' sense that the country was permanently changed by Sept. 11 appears to be slowly eroding. Eight in 10—83 percent—believe the attacks "changed this country in a lasting way," down from 91 percent in December. Six in 10 said Sept. 11 had permanently changed their personal lives. Half of those whose lives had been affected said the changes were for the better. But the other half said those changes were for the worse—nearly double the proportion who had expressed that view 10 months ago. "I was flying before. I haven't flown since," said Anatoly Savich, 28, a furniture- maker who lives in Syracuse, N.Y., and is a native of Ukraine. "Before, we lived not worrying about anything. But now, I have fear of going to another country, even my home country. By a 2 to 1 margin, those who said their lives had been altered said it mainly affected the way they thought about things, and not how they lived. "I just think how it makes you realize that you do have to appreciate the things you have in the right now, because you don't know how long you will have them and when it will be changed," said Anne Imhoff, 54, a bookkeeper from Fort Thomas, Ky. A total of 1,003 randomly selected adults was interviewed Sept. 3 to 6 for this survey. Margin of sampling error is plus or minus 3 percentage points. The survey was designed to see how Sept. 1 1 continues to affect Americans' thinking about their country and its institutions. It included many questions first asked in Post polls conducted immediately after Sept.. 1 1, as well as selected questions from other major surveys. Immediately after the attacks, America seemed to change its mind. Bush—elected with fewer than half the votes cast 10 months earlier—became instantly and almost universally popular. His job approval rating soared from 55 percentin early September to 92 percent one month later as Americans rallied behind their president. The proportion of Americans who said they trusted the federal government doubled from 30 percent in 2000 to 64 percent in late September—a level of confidence not seen since the early days of the Vietnam War. Confidence in the military and the presidency bumped up. Surveys showed that Americans were feeling more patriotic, more charitable, more religious and more committed to their families and one another. The size and breadth of these changes "put Sept. 11 in a class by itself" in terms of its effect on public thinking, said Tom Smith, dean of American trend-watchers and director of the General Social Survey at the University of Chicago's National Opinion Research Center (NORC). The attacks on New York and Washington paled in comparison to such "transforming eras" as the Depression and World War Il as an agent of social change, but "if we put it up against a single incident, one domestic disturbance or single foreign policy crisis, it has no equal," Smith said. Today, one year after America changed its mind about so many things, the country appears to have changed its mind back on some matters—but not all. Bush's job approval rating has declined every month since October. Currently, 69 percent of the public approves of the job Bush is doing —23 points below its October high of 92 percent and 14 points higher than in a Post-ABC News survey conducted a week before the terrorist attacks. The rally 'round Bush that began immediately after the attacks created a halo effect that drove up his job rating even in areas far removed from terrorism and national security, such as education policy and Social Security. Today, those spillover spikes mostly have vanished, the poll found. Even opinion on the president's handling of the war on terrorism is in slow retreat. Today, 70 percent approve of the way Bush is managing the war—13 percentage points down from July and 22 points down from October's high. More ominously for the White House, support for military action against Iraq has dropped from 78 percent in November to 64 percent today. "1 don't particularly care for all this war talk about Iraq," said Delbert Olson, 78, a retired chemical plant worker from Niles, Ohio. Saddam Hussein "will probably be in a bunker so far below they'll never kill him, so I don't think it's worthwhile. Why should we lose our boys?" The majority of Americans continue to say that the government is doing enough to protect the rights of average citizens, American Muslims and even terrorist suspects. But the poll suggests that concern about civil liberties is slowly growing. One in three say the government is not doing enough to protect the rights of those under investigation for terrorist involvement, up 12 points from November. Four in 10 said they would oppose giving security agencies broader authority if it meant reducing personal privacy, up 18 points from last September. Trust in the federal government, defined broadly, has also eroded. Forty percent of Americans say they trust the federal government—down from 64 percent last September. Confidence in the government's ability to handle economic and social problems also has dropped somewhat from its post-attack highs. "These spikes in a feeling of connection and patriotism are very common after catastrophes—this spike has lasted longer than the spike during the Gulf War," said Robert Putnam, a Harvard political scientist. But Putnam also believes there is a possibility of renewal. ' 'If we remember this in lugubrious terms, that won't help to keep a sense of obligation and community. But if we commemorate the event as having given us a glimpse of our better selves .. it doesn't have to go away, and it could be renewed," he said, though conceding "it won't be an easy task." In fact, some government institutions have retained much, if not all, of the resurgent public confidence that immediately followed the attacks. Confidence and pride in the military increased after Sept. 11 and remains strong. Today, more than 3 in 4 Americans—78 percent—said they had confidence in the military, up from 66 percent before the terrorist attacks. Other recent surveys have shown that support for police and firefighters grew and has not wavered. Smith said he expects confidence in the military and other government agencies with defense and security-related responsibilities to remain strong, at least for the foreseeable future. "As long as the military is actively engaged and shows some success, you'll have this heightened confidence and pride," he said. Patriotism and pride in this country's accomplishments continue to flourish, too, particularly in those areas most directly related to defense and national security. Eight in 10—81 percent—said they were "very proud" of the armed forces. That's up from 47 percent in a survey conducted in 1996 by NORC. Similarly, 7 in 10 said they were "very proud" of America's scientific and technological accomplishments, up from half six years ago. Pride in America's democratic traditions, history and economy also experienced sharp increases and remain much higher than in 1996, though each has dropped in the past year. Some aspects of American life seemingly far removed from defense or security continued to benefit from the wave of patriotic feelings. Although Bush's popularity has waned, Huckleberry Finn and other pillars of American literature and art seem to enjoy continued broad public support: Nearly half of all Americans—46 percent—said they were "very proud" of American literature and art, up from 28 percent in 1996 but a decline from 56 percent in late September. Smith said he expects that particular measure of national pride to continue to fall. ' 'The ones that were the product of the halo effect, the ones less relevant to defense and national security, are all coming down and likely will go away." But then he paused, chuckling at the memory of last year's public opinion rallies. "Heck, if we had asked people then how proud they were of American advertising or something else equally as appalling, it would have been high, too." 0 2002 THE WASHINGTON POST t, i)

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

The Western Carolinian is Western Carolina University's student-run newspaper. The paper was published as the Cullowhee Yodel from 1924 to 1931 before changing its name to The Western Carolinian in 1933.

-