Western Carolina University (21)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- George Masa Collection (137)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (3080)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (422)

- Horace Kephart (973)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (89)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (318)

- Picturing Appalachia (6617)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (153)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1463)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (67)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (2008)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (3032)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1945)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (195)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1680)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (556)

- Graham County (N.C.) (238)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (525)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3573)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4925)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (35)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (13)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (421)

- Madison County (N.C.) (216)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (135)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (982)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (78)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2185)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (86)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (192)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (3)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Digital Moving Image Formats (2)

- Drawings (visual Works) (185)

- Envelopes (101)

- Exhibitions (events) (1)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (823)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1045)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (6090)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Notebooks (8)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (194)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12977)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (6)

- Portraits (4568)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (181)

- Publications (documents) (2444)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Relief Prints (26)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (1)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (802)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (18)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (329)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (462)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1482)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (36)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1923)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (190)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (111)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (2012)

- Dams (108)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (63)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1198)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (47)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (122)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (9)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (72)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

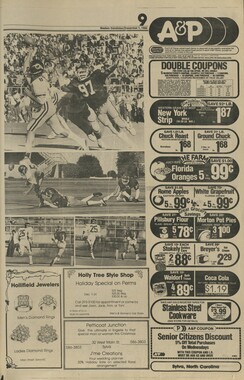

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

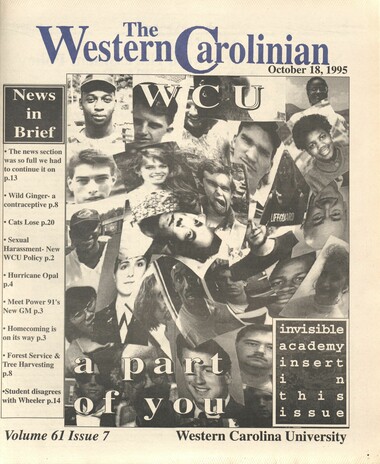

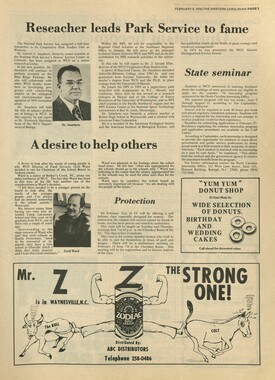

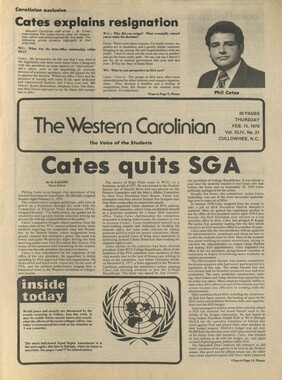

Western Carolinian Volume 61 Number 07 (08)

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

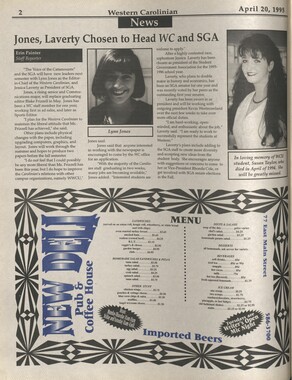

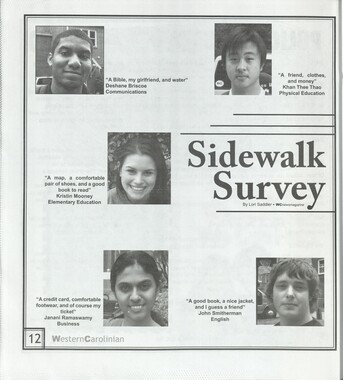

riO.19.95 invisible academy 19 Philip Daughtry's Celtic Blood Celtic Blood is an anthological look at the poetry of Philip Daughtry, a native of the Geordie region of Northern England. Daughtry was the male of a set of fraternal ins born during an air raid outside the town of Newcastle, in 1942. Even though he's a native of the U.K., his grandmother as Thomasina James-a relation of out- aw brothers Frank and Jesse. In 1957, Daughtry crossed the ocean to live on the Crcc Indian Reservation in Canada. In 1961, he came to New York, stayed briefly and meandered his way west to chase the phantoms of his renegade kindred, in blood and in spirit. The trek west was the beginning of a bold poetic venture; and from the beginning I want to say that this book is solid proof that it has been a fruitful one. Thomas Rain Crowe, the publisher of Celtic Blood, mentions that he has seen '[Daughtry] change his voice/colors from urban outlaw, to backcountry eco-activist, to Gaelic Bard, to Hollywood screenwriter, to cowboy poet." The five sections of this book reflect many facets of Daughtry's ancestry, social concerns, spirituality, and most importantly—his lyric visions. I have detailed my favorite selection from each Part to show you the dynamics of this collection. Section one, "Early Poems (1968- 1973)" is short & succinct. "Brazil '68" takes a big stab at everybody in Bhopal, India's favorite company: the attribution reads Gracias al (thanks to) Union Car- de chemical Company. It details a protest of "little people" against this mammoth corporation. The bard explains: "...we marched twenty mjieS) tWenty miles tQ these pipes 0ulm8 *e river/ and no-one is here. No- one to hear us... but iron and steel hum in . ^ver/ while the government does noth- In8- A classic example of the constant "swimming upstream" feeling I share with Daughtry when I consider fighting the megaconglomerate bullies of the world (i.e. Union Carbide, Sony, the Vatican, etc., etc.). Of all the lines in the second section, "The Stray Moon (1975)," those from "Mulch" gripped me the most. Daughtry proclaims boldly: " there is no leaving/ no quitting this Earth... one day/ (you will be grapes) loodi Philip Daughtry gathered for new wine." "Mulch" puts a fresh and interesting spin on the "fi/G ONE" In the middle of "Kid Nigredo (1978)," the third section, is the poem "Oil." This poem takes a more personal look at the world than my two previous examples. In a nutshell, this poem, as represented through lines like "The wife lies/ on her back/ lives open/ to their nightly drilling... he slaves/ hypnotized/ by their own blood pumping/ pumping/ pumping" is a metaphor for the 'bump "n' grind.' You have to speak metaphorically on this subject or you're the most rotten schmuck in the community. This poem is a pearl in the stomach of a country too hung up on the triviality of se mantics. "Celtic Blood (1980-1988)" is the name of part four. All of these poems are written in Daughtry's native Geordie dialect. I know there are many of you out there that are interested in Celtic culture and heritage, and these selections are sure to transport you to wartime and postwar North England when the British government "coerced" the Geordies into feeding the war and rebuilding efforts with coal (the North of England is laden with it). My favorite Geordie selection is "Wiccae." a scathing look at the old practice of burning outcasts and nonconformists at the stake in a passionately Christian (and hypocritical) way. An excerpt: "...(the righteous) dragged our wyrd lasses oot / an threw them on a fire... aye, even used Jesus' cross/ for flames... Ye can still see the ashes... wounding the clearest streams." My favorite piece from whole book is "The Man Who Saw God," from the final section, entitled "Crouching Over the Kill (1984- 1994)." I read this poem for the first time the day after my grandmother's funeral in July. Through some "coincidence" I opened the book to this page; I had only browsed the front of the book before. My grandmother was of 100% Celtic heritage and was proud to tell everybody the story of her Dad coming from Ireland. At 18 he had worked on a fishing boat to save the money (about $50) for the voyage. I remember her sitting on the porch in her rocker and quietly singing Irish folk ballads like "I'll Take You Home Kathleen," "Danny Boy," or 'The Irish Blessing." Daughtry's profound words helped me come to grips with my loss of Celtic Blood. Celtic Blood is available at the WCU bookstore, City Lights Books in Sylva, and Malaprop's Bookstore in Asheville; or you can order it directly from the publisher. Write to: New Native Press, PO Box 661, Cullowhee, NC 28723. —James Gray Anne Rice's New Devil Lestat's a wanted vampire. Yes, you've read that line before, but this time, it's serious. In Memnoch the Devil, Anne Rice's latest vampire adventure, Lestat is caught in a web so distorted that even a spider dares not claim it; a decision that will inevitably seal his fate. Rice allows her favorite lover and nightcrawler to be a pawn piece in the chess game of existence between God and the Devil. With terrific cameo appearances by Louis, Armand, Maharet, and the newly-transformed fledgling vampire David Talbot (of Taiamasca fame) the novel opens and we find Lestat de Lioncourt on a two-year prowl for a victim for which he's gained an affection. This victim, an avid extortionist of fine art and holy relics, has such great value to Lestat that he can barely stand to suppress his desire to feed upon him... yet, he does. What causes this curious craving in Lestat for this mortal that has lasted two years? Maybe it's the eerie footfalls he hears every time he gets near this victim until one day the owner announces, "I am the Devil. I am winning the battle...and I need you!" Anne Rice, the "dedicated scholar of the New Age" (as she deems herself), gives a gutsy attempt to challenge the very limitations of our existing world. She treads where no author dares to stray. A tale she claims that possessed her, she firmly found the trip exciting and critics agree with her outlook regarding Memnoch the Devil as the "magnum opus" of her entire book collection. The novel takes the fight between good and evil a ladder up from Stephen King's more earth-bound epic, The Stand, yet she seems to give a solution for every piece written by devoted authors who've questioned existence, like Milton and his Paradise collections. —Natasha Tyson John Ashberyfs And The Stars Were Shining John Ashbery is one of the most impor- Jt American poets of the latter half of this Ne^v He haS °ften been associated with the with K°rlC Scn°o1' having much in common but h bizarre WIt and rampaging imagery, (h ne has never been actually classified with group. He is the only poet ever to win all Pup tbe natlons major prizes—the nzer, the National Book Award and the same"3' B°°k Crit'CS Circle Award—in the im ° year His poetry is dark, brooding, often witr,enelrable"and stuffed bey°nd the seams b00|tlr?ny" With the Publication of his latest nex h the Stars Were Shinin8> a new an~ wav "S been built on his ever-dynamic, al- J*var>t garde," poetic style. "Us book is shows fully Ashbery's un dying allegiance to the aesthetic, however twisted his take on it may be. These poems are about understanding the fleeting and chaotic world in the way only Ashbery can do it. His genius is in his conciliatory tone. It is always so open ended. The book itself ends with, "It was as if all of it had never happened,/my shoelaces were untied, and-am I forgetting anything." He is ever elusive, constantly veering away from closure. In fact, it is hard to say this book is really about anyth.ng in particular because it is almost imposs.ble to say that the poems have a main theme. As soon as one decides what the point of a particular poem is the contradictions to that decision immediately arise. If this book can have an emphas.s, it would be its all-inclusiveness—the interconnectedness of lives, as he says in the title poem, "like a woman's stocking, that you lay flat and it becomes a unit of your life and... ... of so many others lives as well." You will find much of Ashbery's classic been-through-the-blender lyricism, but here it is not as evident as in some of the denser books (Flow Chart, Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror). Here the reader finds moments, in fact entire poems, where the syntax is not as jagged: "The stars were still out in the field, and the child prostitutes plied their trade, the only happy ones, having learned how happiness sticks and will not risk being traded in for a song or a balloon." This book is a great book, and Ashbery a great poet, not only because the poems are innovative and desperately escape all categorization and expectation, but more because they are able to grasp a human condition of persistence in an unending, chaotic world. Ashbery has been able to communicate in this, his latest book, without ever saying. There is no point of understanding in these poems; but the reader, having completed this book, is emotionally altered. The poet has achieved the ability to forge a link to the minds and emotions of his audience by eliciting a mood rather than a direct explication of ideas. —Jimmy McLachlan

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

The Western Carolinian is Western Carolina University's student-run newspaper. The paper was published as the Cullowhee Yodel from 1924 to 1931 before changing its name to The Western Carolinian in 1933.

-