Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (292)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2766)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1388)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (1794)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2569)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1923)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (161)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1672)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (233)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (519)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3524)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4694)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (25)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (12)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (212)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (981)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2115)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (84)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (184)

- Envelopes (73)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (815)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (5835)

- Newsletters (1285)

- Newspapers (2)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (6)

- Portraits (4533)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (151)

- Publications (documents) (2236)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (15)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Vitreographs (129)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (282)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1407)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1744)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (170)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (110)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (1830)

- Dams (107)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1184)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (38)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (118)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (71)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (244)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

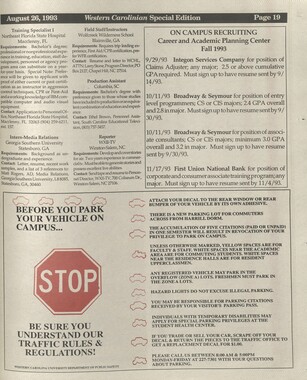

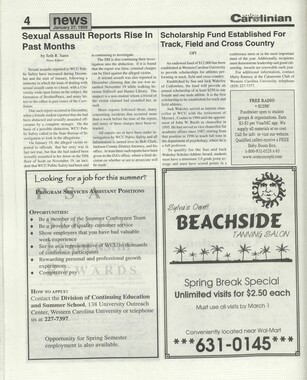

Western Carolinian Volume 29 Number 19 (20)

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

Friday, April 3, 1964 Page 3 Limelight By BILL SHAWN SMITH Five movies have been nominated for an Academy Award as "Best Picture" of 1963. Only one will win. That one is Tom Jones! Tom Jones was made in England; in fact, Tom Jones was made all over England. He is a rowdy, lusty lad with a flashing smile, and, when he ventures near a lassie, Mother Nature shows her stuff. The film opens at the birth of Tom, whom everyone thinks is the bastard son of a squire's servant. The goodly squire banishes the misled girl and takes the child to be one of his own. Tom grows into a more than healthy young man with a defin. ite eye for the young ladies. But, alas, the squire has a real son. The real son is . . . well how show we say? ... a prude and very jealous of Tom. When Tom isn't rolling in the hay with the peasant girls he is persuing the buxom, blonde daughter of another local squire. The particular miss feels the same way about Tom, but Tom is, for all his charm, a bastard. Thus, blondic is engaged to the stuff- shirt fop, the real son of Tom's squire. Eventually, Tom is driven from the squire's house and travels to London, via a few taverns and a few more ladies. One of the ladies, turns out to be the girl whom the squire ban ished as being Tom's mother. Tom is prevented from a romp in the inn with her only in the nick of time. Also on the path is blondie. She runs away in order to prevent marriage with sweetie-pie. In London, Tom suddenly finds himself being kept by one of the town's leading society matrons. The plot thickens. Tom lands in jail, is about to be hanged when a good old Key- ston cop chase saves the day. Tom proves to be, in reality, the true and legal nephew of the squire who reared him. Now that Tom is legal, he is free to marry his true love. Albert Finney as Tom is great! He smiles, and the screen comes alive. Finney plays Tom without complexities; he is just a hell- raising, woman loving, honest, charming bastard. Finney's performance should read an Oscar for him as "Best Actor." He certainly is ! ! English director, Tony Richardson has pieced together a cinema masterpiece of that long lost ingredient, entertainment and fun. There is no overbearing moral, and Richardson doesn't try to make one. Tom Jones is a movie you'll want to see over and over again. Tom Jones is definitely the very "Best Movie" of 1963. Candid Campus by Jerry Chamber* Among the most pressing dilemmas facing the American college student is the question of ethics and morality. According to most critics of this generation, morality is disappearing, fast becoming a "thing of the past." If this is the case, why then, should students trouble themselves with social mores? Sights And Insights By Don Yarbrough Fortunately, this is not the case; no nation can survive without some sort of ethical system. The moral structure is not disappearing, It is only changing with the times. Even morality is subject to the law of change, though some people continually refuse to admit It. We are caught up in the twentieth century, even here In the mountains of Western North Carolina. A great part of the conflict in the mind of the student is generated by the intensely materialistic philosophy that confronts him everywhere. Everything is placed on a monetary plane and the idea seems to be "Do anything you can to get ahead, but don't get caught doing it." This is drilled into our heads from the time we are old enough to assimilate and digest ideas. The drilling is done by adults and by the communications media — radio, television, and movies — both subtly and directly. Success, not happiness, is the important thing in life. As a result, many students- are prone to follow courses of study which seem to offer the most lucrative rewards in salary and social prestige, rather than studying something he is greatly interested in. This generation promises to be the most bored and dissatisfied generation in the history of mankind. As upper classmen we often take a backward glance at those days in the Freshman dorm. Remember when you got together with those guys, several in one room, and you proceeded to solve all the problems of the world? Almost invariably the talks began with the subject of drinking, went from there to sex, and ended on religion? There was always that fellow who had never questioned any of his beliefs before, and there was always the fellow who had it all figured out. He boldly proclaimed he was an atheist, and everybody sat up with momentous fascination. It caused you to take a little closer look at things, and most of all, yourself. You might also recall that you never really resolved anything; you merely brought to the surface the fact that you don't quite know it all. I remember those bull sessions quite well, and I still engage in them occasionally. You know you'll never prove anything, only complicate matters. But somehow all the old questions still pop up: What is man? Why is man? Who is God? What is life all about? Frequently you think you used to be able to give better answers then than you can now. However that may be, these age-old questions are what keep us moving, keep us living. The thing that used to frustrate me to no end was paradox. Just when I thought I had the answer to some big philosophical question, I suddenly found myself up against a brick wall. There was not even a temporary answer anywhere in sight. For example, after the bases for religions had been expertly ruled out (their logical structures were all a little shaky), I discovered there were few answers to anything, really, and I no longer had any real thing on which to lean. "Faith without reason is dead," I used to say; I saw no reason in anything, and it seemed there was no point in living. To be caught in the "horns of a dilemma" or faced with the paradoxical was just too much for me to bear. I had to have an answer! Consequently, I would go off into periods of depression. It's a terrible feeling when nothing fits, nothing makes sense, and you know that submission to faith is a comfortable, easy way out, but that such a method would not totally satisfy you. Well, in 1964 the same old questions are still with me. I find that many of my old philosopher-pals have just plain given up the quest, or they've settled down into some sort of system which seems to satisfy all their previous self-controversy. Man has to have a belief in order; he has to make ends meet. And if things don't fit, he somehow shoves them into place. He forces his beliefs to agree and balance even if he has to rationalize, lie to himself, or make realities out of illusions. Indeed, admitting that everything ends in paradox (as far as human understanding is concerned) is no easy task. It's an uncomfortable cross to bear (to borrow an old expression); not to have any firm stakes driven in the rgound is sometimes sufficient cause for suicide. But there is a little secret I recently stumbled upon which alleviates some of this pain. Paradox is the spice of life! What a non-sense world this would be if everything made sense! The imbalance keeps the ball rolling. Had we all-Knowledge, we'd be bored stiff. Real joy emanates from what is not known, not what is known. Everywhere he goes the student is reminded that this is a dog-eat-dog world. It makes no difference who you step on on the way "up," just so long as you get there. In a competitive society of this sort, there is little room left for the Christian ethic of love and tolerance. Little wonder that morals are "degenerating"! It is one thing to flout convention openly and an entirely different thing to flout it covertly, as so many of our self-styled moralists do. The people who raise the loudest hue and cry about sin and immorality are usually the ones most guilty of these transgressions. When a student comes to college, he is expected to be adult enough to carry out and meet his own responsibilities, whether they be moral, social, or financial. The student also expects to find an atmosphere in which he can fully develop his own attitudes and ideals, a place to experiment and to find himself. NO ONE can tell the student what to do or what to become or believe. The advice and experience of others cannot be relied upon completely; at one time or another, decisions must be made indepently. The college cannot attempt to guard the individual morals of over 2,000 students and expect to meet with a great amount of success. Ridicule is the first and last argument of fools. — Charles Simmons I now know that wars do not end wars.—Henry Ford Pa: ence is the key of content.—Mahomet COMBO DANCE MAGRUDER FOR PRESIDENT Sponsors "The Shadows" of Waynesville Monday, April 6 — 6:30-9:00 Hunter Gallery On Campus with MaxShulman {Author of Holly Round the Flag, Boys!' ttnd "Barefoot liny With Cheek.") WELL-KNOWN FAMOUS PEOPLE: No. 1 This is the first in a series of 48 million columns examining the careen of men who have significantly altered the world we live in. We l>cgtn today with Max Planck. Max Planck (or The Pearl of the Pacific, as he is often railed) gave to modern physics the law known as Planck's Constant. Many people when they first hear of this law, throw up their hands and exclaim, "Clol'ly whiskers, this is too deep for little old me!" (Incidentally, speaking of whiskers, I cannot help hut mention Personna Stainless Steel Razor Blades. Personna is the blade for people who can't shave after every meal. It shaves you closely, cleanly, and more frequently than any other Stainless steel blade on the market. The makers of Personna have publicly declared -and do here repeat—that if Personna Blades don't (rive you more luxury shaves than any other stainless steel Hade, they will buy yon whatever Mi le you think is better. Could anything be more fair? I, fur one, think not.) fotitd w in But I digress. We were speaking of Planck's Constant, which is not, as many think, difficult to understand. It simply states that matter sometimes behaves like waves, and waves sometimes behave like matter. To give you a homely illustration, pick up your pencil and wave it. Your pencil, you will surely agree, is matter—yet look at the little rascal wave! Or take flags. Or Ann-Margret. Planck's Constant, uncomplicated as it is, nevertheless provided science with the key that unlocked the atom, made space travel possible, and conquered denture slippage. Honors were heaped upon Mr. Planck (or The City of Brotherly Ixrve, aa he is familiarly known as). He was awarded the Nobel Prize, the Little Brown Jug, and Disneyland. But the honor that pleased Mr. Planck most was that plankton were named after him. Plankton, as we know, are the floating colonies of one-celled animals on which fishes feed. Plankton, in their turn, feed upon one-half celled animals called krill (named, incidentally, after Dr. Morris Krill who invented the house cat). Krill, in their turn, feed upon peanut butter sandwiches mostly—or, when they are in season, cheeseburgers. But I digress. Back to Max Planck who, it must be said, showed no indication of his scientific genius as a youngster. In fact, for the first six years of his life he did not speak at all except to pound his spoon on his bowl and shout "More gruel!" Imagine, then, the surprise of his parents when on his seventh birthday little Max suddenly cried, "Papa! Mama! Something is wrong with the Second Law of Thermodynamics!" So astonished were the elder Plancks that they rushed out and dug the Kiel Canal. Meanwhile Max, constructing a crude Petrie dish out of two small pieces of petrie and his gruel bowl, began to experiment with thermodynamics. By dinner time he had discovered Planck's Constant. Hungry but happy, he rushed to Heidelberg \ 'ni versity to announce his findings. He arrived, unfortunately, during the Erich von Stroheim Sesquiceotennial, and everyone was so busy dancing and duelling that young Planck could find nobody to listen to him. The festival, however, ended after two vears and Planck was finally able to report his discovery. Well sir, the rest is history. Einstein gaily cried, "E equals mc squared!" Edison invented Marconi. Eli Whitney invented Georgia Tech, and Michelangelo invented the ceiling. This later became known as the Humboldt Current. # MM UK I Afr. Shulman is, of course, joshing, but the maker* ot Personna Blades are not: if, after trying our blades, you think there's another stainless steel blade that gives you more luxury shaves, return the unused Pereonnas to Box r>00, Staunton, Va., and we'll buy you a pack of any blade uou think is better.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

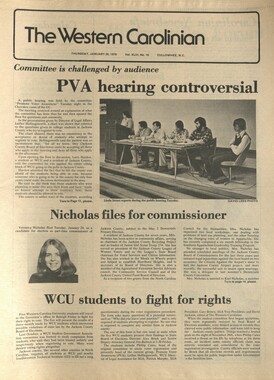

The Western Carolinian is Western Carolina University’s student-run newspaper. The paper was published as the Cullowhee Yodel from 1924 to 1931 before changing its name to The Western Carolinian in 1933.

-