Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (26)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1388)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (1794)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2399)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1917)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (161)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1671)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (233)

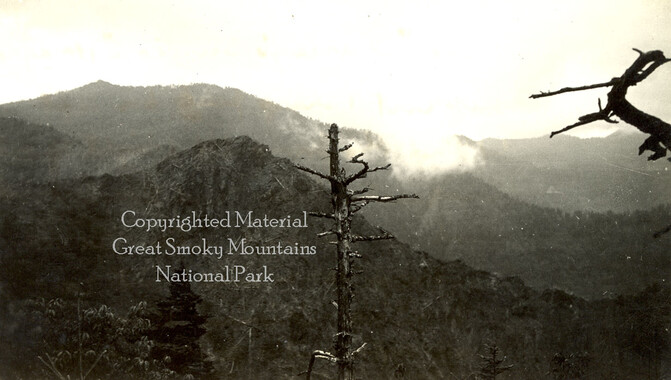

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (510)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3522)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4692)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (25)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (12)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (211)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (981)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2113)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (247)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (73)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (184)

- Envelopes (73)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

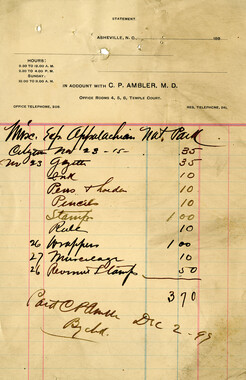

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (812)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (619)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (5835)

- Newsletters (1285)

- Newspapers (2)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (7)

- Portraits (1960)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (151)

- Publications (documents) (2237)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (15)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Vitreographs (129)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

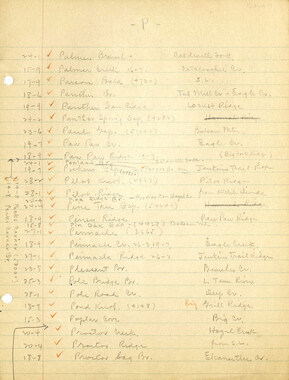

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (282)

- Cataloochee History Project (65)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1407)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1744)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (167)

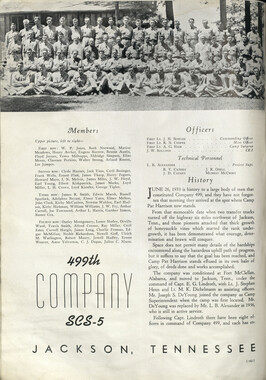

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (110)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (1830)

- Dams (103)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1058)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (38)

- Landscape photography (10)

- Logging (103)

- Maps (84)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

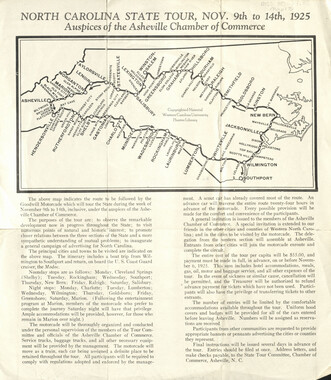

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (71)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (245)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

National Parks Bulletin

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

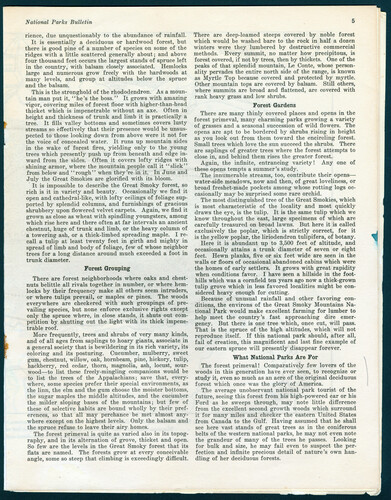

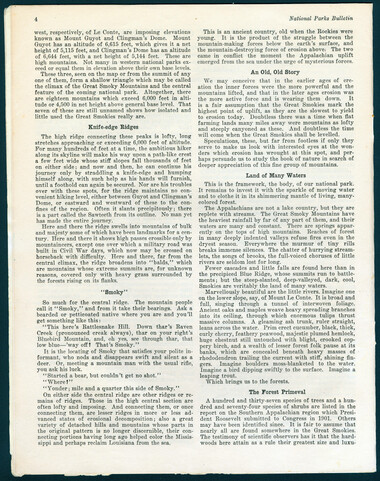

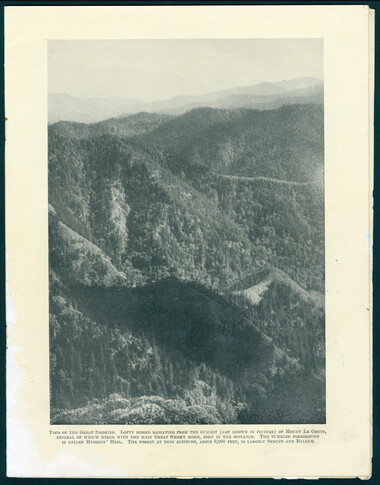

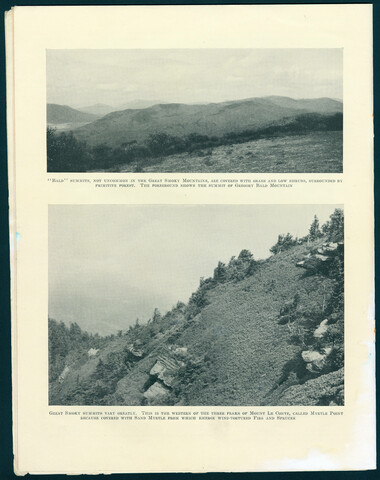

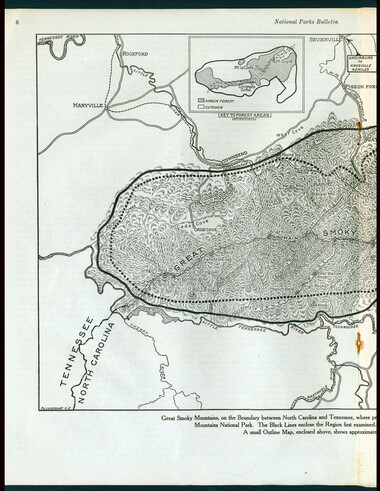

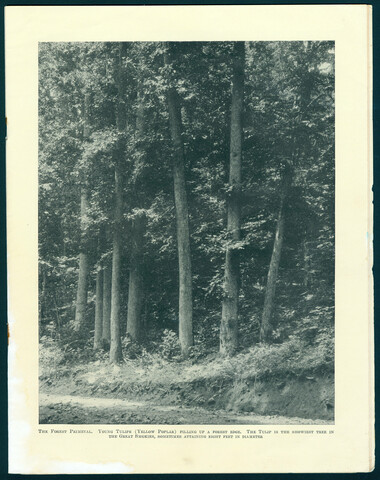

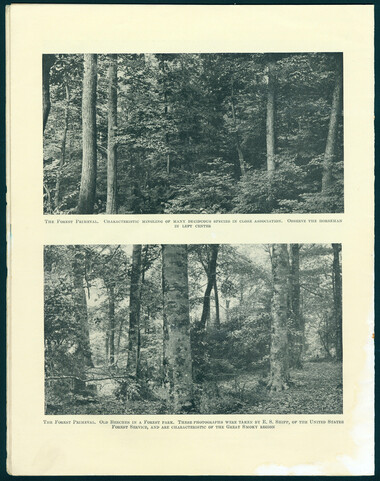

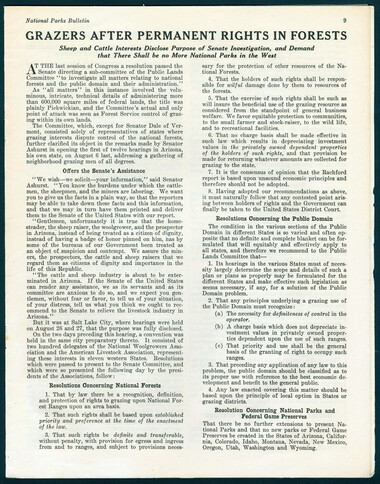

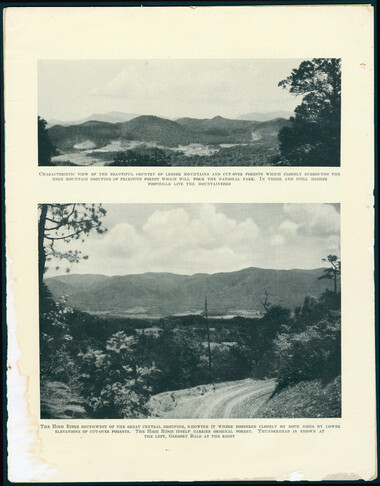

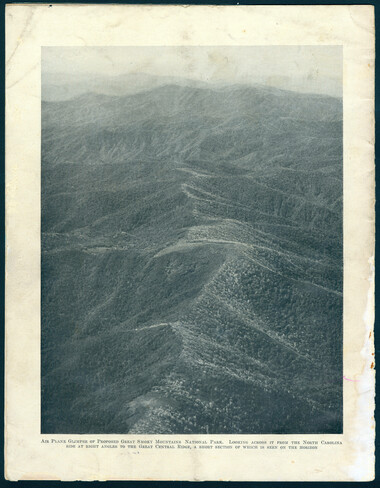

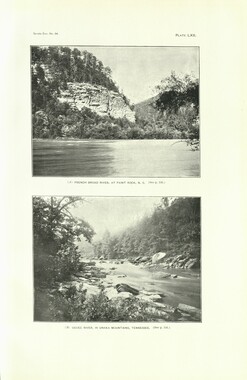

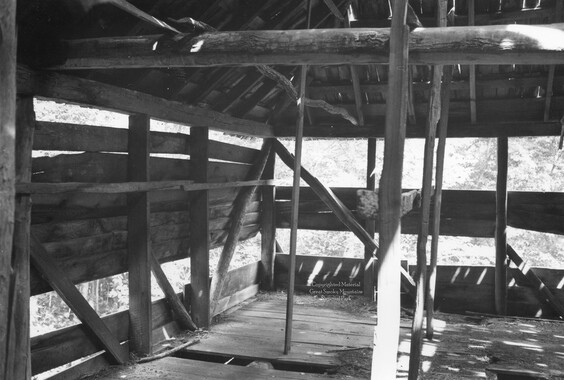

National Parks Bulletin rience, due unquestionably to the abundance of rainfall. It is essentially a deciduous or hardwood forest, but there is good pine of a number of species on some of the ridges with a little scattered generally about; and above four thousand feet occurs the largest stands of spruce left in the country, with balsam closely associated. Hemlocks large and numerous grow freely with the hardwoods at many levels, and group at altitudes below the spruce and the balsam. This is the stronghold of the rhododendron. As a mountain man put it, " he's the boss.'' It grows with amazing vigor, covering miles of forest floor with higher-than-head thicket which is impenetrable without an axe. Often in height and thickness of trunk and limb it is practically a tree. It fills valley bottoms and sometimes covers lusty streams so effectively that their presence would be unsuspected to those looking down from above were it not for the voice of concealed water. It runs up mountain sides in the wake of forest fires, yielding only to the young trees which presently push up from beneath and edge inward from the sides. Often it covers lofty ridges with shining armor, where the mountain people call it "slick" from below and "rough" when they're in it. In June and July the Great Smokies are glorified with its bloom. It is impossible to describe the Great Smoky forest, so rich is it in variety and beauty. Occasionally we find it open and cathedral-like, with lofty ceilings of foliage supported by splendid columns, and furnishings of gracious shrubbery upon flowered velvet carpets. Again, we find it grown as close as wheat with spindling youngsters, among wThich rise here and there often at far intervals an ancient chestnut, huge of trunk and limb, or the heavy column of a towering ash, or a thick-limbed spreading maple. I recall a tulip at least twenty feet in girth and mighty in spread of limb and body of foliage, few of whose neighbor trees for a long distance around much exceeded a foot in trunk diameter. Forest Grouping There are forest neighborhoods where oaks and chestnuts belittle all rivals together in number, or where hemlocks by their frequency make all others seem intruders, or where tulips prevail, or maples or pines. The woods everywhere are checkered with such groupings of prevailing species, but none enforce exclusive rights except only, the spruce where, in close stands, it shuts out competition by shutting out the light with its thick impenetrable roof. More frequently, trees and shrubs of very many kinds, and of all ages from saplings to hoary giants, associate in a general society that is bewildering in its rich variety, its coloring and its posturing. Cucumber, mulberry, sweet gum, chestnut, willow, oak, hornbeam, pine, hickory, tulip, haekberry, red cedar, thorn, magnolia, ash, locust, sour- wood—to list these freely-mingling companions would be to list the trees of the Appalachians; save that, everywhere, some species prefer their special environments, as the linn, the elm and the gum choose the moister bottoms, the sugar maples the middle altitudes, and the cucumber the milder sloping bases of the mountains; but few of these of selective habits are bound wholly by their preferences, so that all may perchance be met almost anywhere except on the highest levels. Only the balsam and the spruce refuse to leave their airy homes. The forest primeval is quite as varied also in its topography, and in its alternation of grove, thicket and open. So few are the levels in the Great Smoky forest that its flats are named. The forests grow at every conceivable angle, some so steep that climbing is exceedingly difficult. There are deep-loamed steeps covered by noble forest which would be washed bare to the rock in half a dozen winters were they lumbered by destructive commercial methods. Every summit, no matter how precipitous, is forest covered, if not by trees, then by thickets. One of the peaks of that splendid mountain, Le Conte, whose personality pervades the entire north side of the range, is known as Myrtle Top because covered and protected by myrtle. Other mountain tops are covered by balsam. Still others, where summits are broad and flattened, are covered with rank heavy grass and low shrubs. Forest Gardens There are many thinly covered places and opens in the forest primeval, many charming parks growing a variety of grasses and a seasonal succession of wild flowers. The opens are apt to be bordered by shrubs rising in height as you look out from them toward the encircling forest. Small trees which love the sun succeed the shrubs. There are saplings of greater trees where the forest attempts to close in, and behind them rises the greater forest. Again, the infinite, entrancing variety! Any one of these opens tempts a summer's study. The innumerable streams, too, contribute their opens— water-side meadows, now and then, of great loveliness, or broad freshet-made pockets among whose rotting logs occasionally may be surprised some rare orchid. The most distinguished tree of the Great Smokies, which is most characteristic of the locality and most quickly draws the eye, is the tulip. It is the same tulip which we know throughout the east, large specimens of which are carefully treasured on broad lawns. But here it is called exclusively the poplar, which is strictly correct, for it is the yellow poplar, the liriodendron tulipifera, of botany. Here it is abundant up to 3,500 feet of altitude, and occasionally attains a trunk diameter of seven or eight feet. Hewn planks, five or six feet wide are seen in the walls or floors of occasional abandoned cabins which were the homes of early settlers. It grows with great rapidity when conditions favor. I have seen a hillside in the foothills which was a cornfield ten years ago now a thick-grown tulip grove which in less favored localities might be considered heavy enough for cutting. Because of unusual rainfall and other favoring conditions, the environs of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park would make excellent farming for lumber to help meet the country's fast approaching dire emergency. But there is one tree which, once cut, will pass. That is the spruce of the high altitudes, which will not reproduce itself. If this national park should, after all, fail of creation, this magnificent and last fine example of our eastern spruce will presently disappear forever. What National Parks Are For The forest primeval! Comparatively few lovers of the woods in this generation have ever seen, to recognize or study it, even so much as an acre of the original deciduous forest which once was the glory of America. The average unobservant national park tourist of the future, seeing this forest from his high-powered car or his Ford as he sweeps through, may note little difference from the excellent second growth woods which surround it for many miles and checker the eastern United States from Canada to the Gulf. Having assumed that he shall see here vast stands of great trees as in the coniferous belts of the western national parks, he may not even note the grandeur of many of the trees he passes. Looking for bulk and size, he may fail even to suspect the perfection and infinite precious detail of nature's own handling of her deciduous forests. i

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

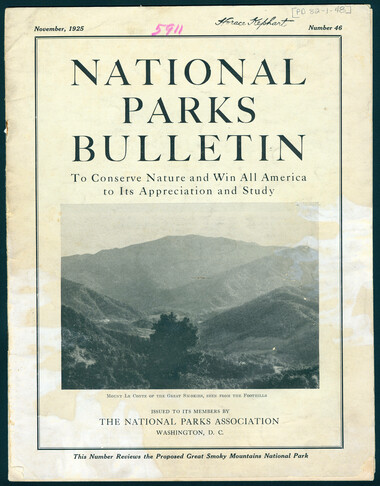

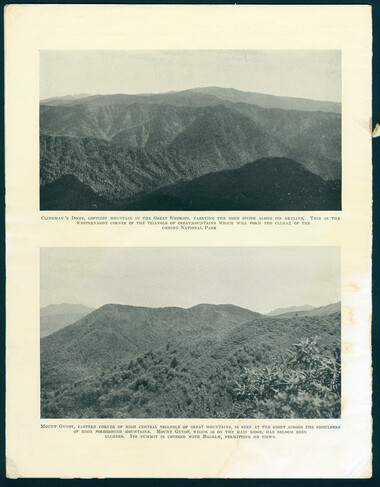

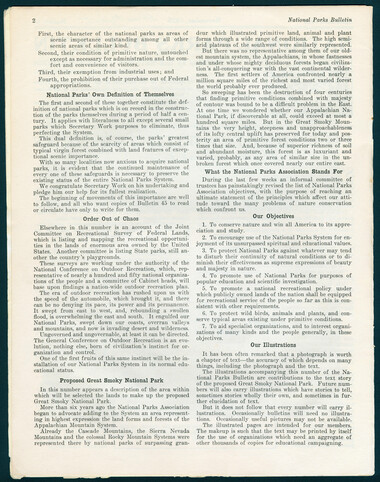

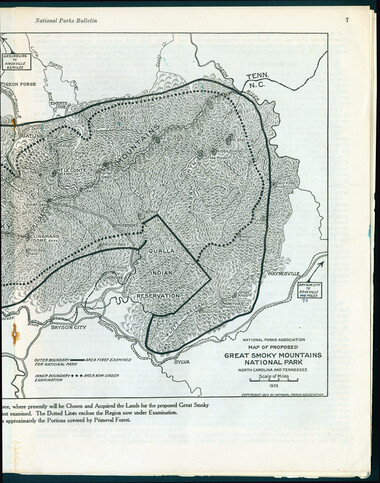

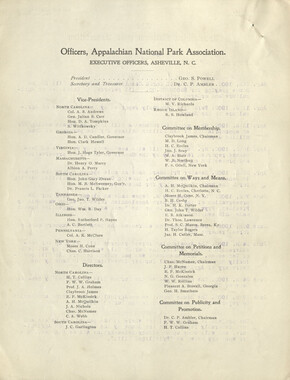

The subtitle of National Parks Bulletin (No. 46), edited by Robert Sterling Yard, reads: “To Conserve Nature and Win All America to its Appreciation and Study” and includes a cover caption indicating its focus on the “Proposed Great Smoky Mountains National Park.” This subtitle and the contents cover issues of conservation, including the “Importance of Government Protection” and a statement “In Support of Secretary Work’s Policy.” With titles sounding defensive, the brochure later reveals that sheep and cattle interests demand “no more national parks.” The bulletin also outlines the purposes of the National Parks Association, a membership organization located in Washington DC.

-