Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (292)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2766)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1388)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (1794)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2569)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1923)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (161)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1672)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (233)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (519)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3524)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4694)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (25)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (12)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (212)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (981)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2115)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (84)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (184)

- Envelopes (73)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (815)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (5835)

- Newsletters (1285)

- Newspapers (2)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

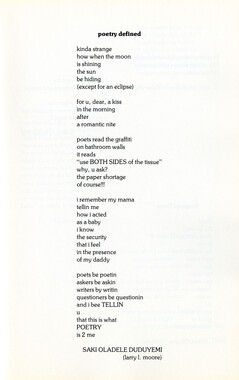

- Poetry (6)

- Portraits (4533)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (151)

- Publications (documents) (2236)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (15)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Vitreographs (129)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (282)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1407)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1744)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

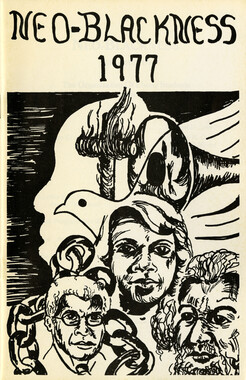

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (170)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (110)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (1830)

- Dams (107)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1184)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (38)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (118)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (71)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (244)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

Levern Hamlin scrapbook

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

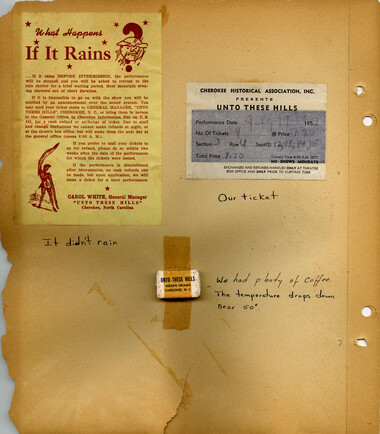

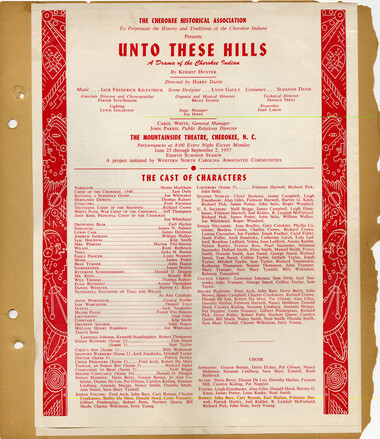

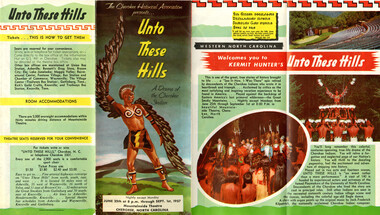

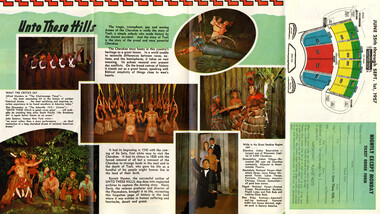

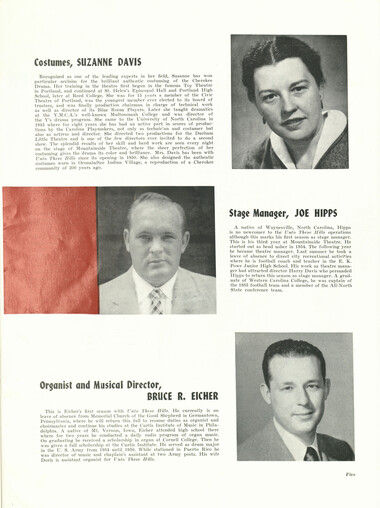

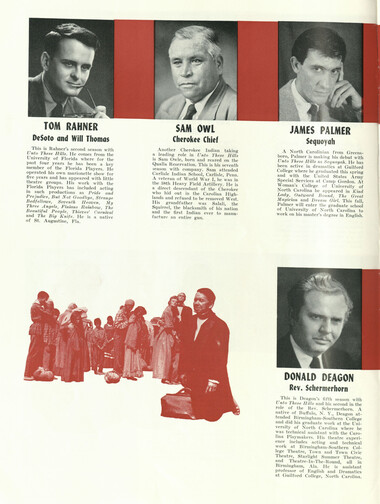

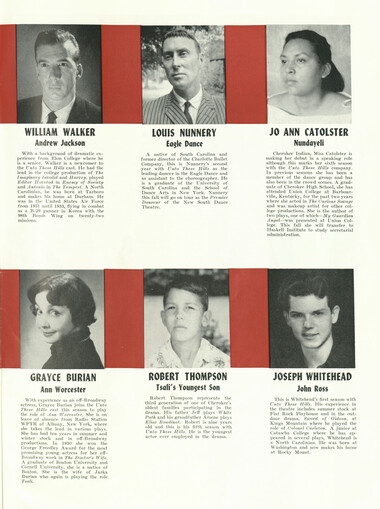

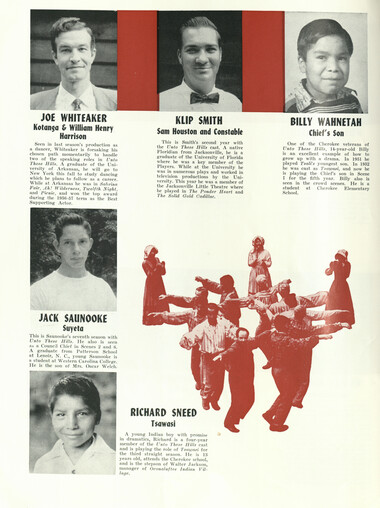

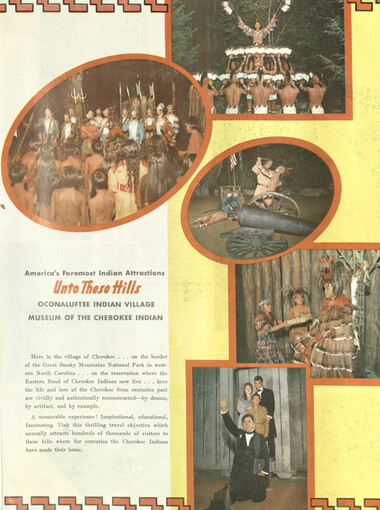

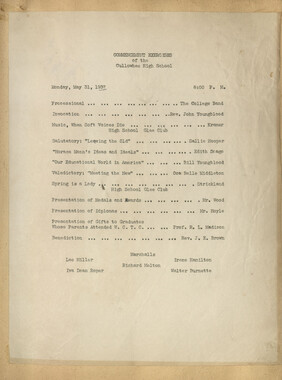

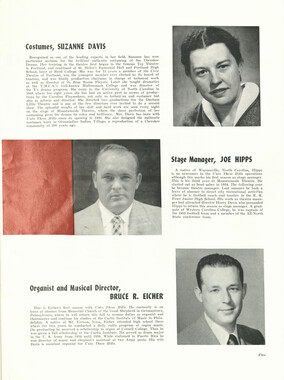

Theatre of the People HARRY DAVIS The "theatre of the people"—drama in the open air—actually was born almost 3,000 years ago. It had its conception in the great amphitheatres of ancient Greece, was nurtured in the Rome of the Caesars, and came of age during the lusky Elizabethan era of England. And then it died. But now, some 400 years later and a continent removed, the "theatre of the people" is coming alive again. It is being revived through the outdoor historical drama right here in America whose history is young. And this summer, a half million persons will sit in open-air theatres and watch the re-creation of history, much of it on the very spot where it was lived and written. Strangely enough, revival of the "theatre of the people" began in North Carolina and was instituted by a North Carolinian and produced on the very spot where the first English colony in the New World was founded. It began with the premiere of Paul Green's now-famous outdoor play, The Lost Colony, at Manteo, on Roanoke Island, N. C. In the wake of this trail-breaking play, more than a dozen other dramas, based on American history have followed, principally in the Southeast, of which Green authored six. The summer of 1950 saw the opening of Unto These Hills, a drama concerned with the impact of white settlers on the ancient civilization of the Cherokee Indians. Presented in the breath-taking sweep of Mountainside Theatre, located in the heart of the Qualla Reservation and with the immemorial peaks of the Great Smokies for a backdrop, this production, like The Lost Colony, has special significance. Written by a hitherto unknown young playwright, it marked the emergence of a new talent in the field of the historcial play, Kermit Hunter. Presented first on July 1, 1950, Unto These Hills has so far broken all attendance records for such plays, piling up a total audience count of more than 1,000,000 persons. The success of Mr. Hunter's first venture into this specialized field of playwrighting has led to his authorship of a number of other historical plays, among them Forever This Land, Horn in the West, Voice m the Wind and 'Chucky Jack. The outdoor historical drama, like the standard commercial play, must pay for itself at the box-office, and must have the fundamental theatrical quality of being, first of all, a good show. But there are many differences between the historical drama of this type and the usual indoor show, a most obvious one being that of subject matter. The Broadway play may treat of almost any conceivable theme, but the topic of the outdoor historical drama is invariably connected with actual events and personalities of the past. Another important feature of the historical play is its direct, indigenous relation to the locale in which it is staged. In nearly all instances the dramatized story, rooted in historical fact, is presented on or near the site where the real story took place. This imparts a valuable spiritual quality into the performance, since it becomes a sort of pilgrimage to holy ground. The historical matter, of course, must have a genuine and important connection with the here and now. Its overtones, its symbols, must speak the spiritual language of the present-day spectator. Inevitably the outdoor historical drama is a drama of patriotism, but its patriotism must be positive and affirmative in the finest sense; it must be a thoughtful patriotism and not a childish flag4vaving in the pep-rally tradition. Though regional in its flavor, the dramatic story must be universal in its appeal. The dry fact that George Washington once slept somewhere is un important to most of us, unless perchance he slept at Valley Forge, at Yorktown or at some other place intrinsically related to American destiny. And American destiny is not limited to yesterday, it is also a thing of today and of tomorrow. In overwhelming proportion the audiences who see these outdoor plays are made up of family tourist groups, a somewhat diiferent audience from that found in the indoor metropolitan theatre. Some are experienced theatre patrons, many are not. Children are present in all age ranges, including babies in their mother's arms. The holiday spirit is predominant, and one wonders, sitting among them, if the crowd in the great open-air theatres of ancient Greece and Rome, even the lusty Elizabethan audience, might not have been very much akin in spirit to this people's audience of our Atomic Age. The likeness to the classic Greek theatre may be carried even further, for here, too, the people are watching a re-enactment of their own past; here, too, the legendary heroes, the forefathers, the founders of the nation, striving mightly with great forces, and showing us first-hand their monumental labors, their enduring faith, their sore trials and their triumphant vision of the future. In theatre of this kind the common brotherhood of man becomes a most palpable reality. Much of the success of these plays must be credited to the dedicated and unselfish contributions of money, time, energy and knowledge given to them by community and civic leaders. Most of them are true community projects, presented by a non-profit corporation, with its top authority resting in an elected Board of Trustees composed of distinguished leaders in the community. The cost of opening a show of this kind will run well into the neighborhood of $200,000, and the weekly operating payroll for a season of three months will average from $5,000 to $10,000. In almost every case the funds to float the initial production must be raised through civic contributions, bolstered occasionally by grants from the State. The State of North Carolina has been especially generous in assisting its historical dramas, since it recognizes quite honestly their great advertising value as high-quality area attractions. In keeping with the regional flavor of these plays, the acting company is usually drawn from local sources. Experienced non-professional actors from schools and commuinty theatres are generally hired for the more difficult roles, and supporting actors and dancers are engaged largely from native residents. Salaries are moderate, but the pay scale compares favorably with the average of most summer stock companies. Unlike the summer stock practice, the emphasis is always on the group, rather than the individual, and hence the capable amateur actor is ordinarily preferred to the Broadway or Hollywood star, regardless of salary considerations. The professional actor, through no fault of his own, is frequently a problem-child, if not a dismal failure, in this type of theatre. His insistent emphasis on individual personality and talent are out of tune with the group spirit, and his subtle shadings of voice and bodily movement are likely to go for naught in the great sweep of the outdoor theatre, where bigness and simplicity are needed. The slickness and versatility so rightly admired on the Broadway stage and the Hollywood screen are not usually suited to the rugged honesty of the pioneer character, which suffuses most of the historical plays. The Carolina Playmakers of the University of North Carolina have been directly associated with the staging of many of the outdoor historical shows. The fact that this type of drama Thirty-nine

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

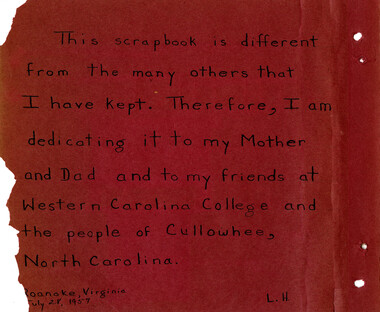

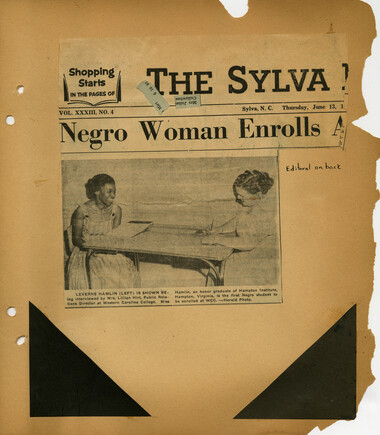

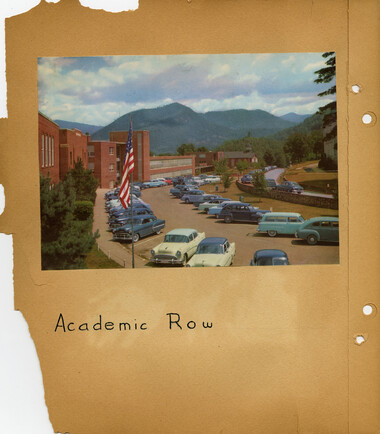

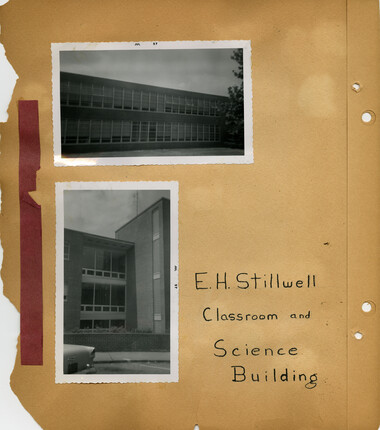

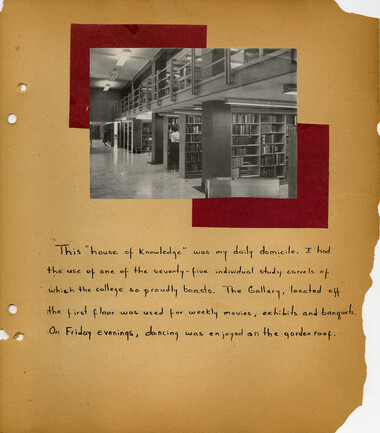

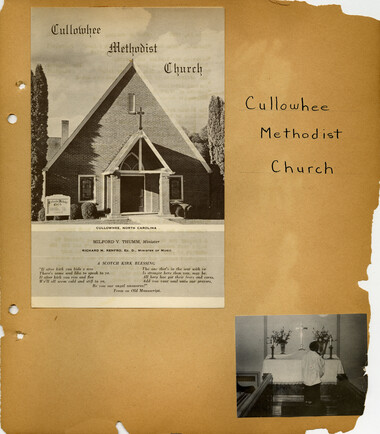

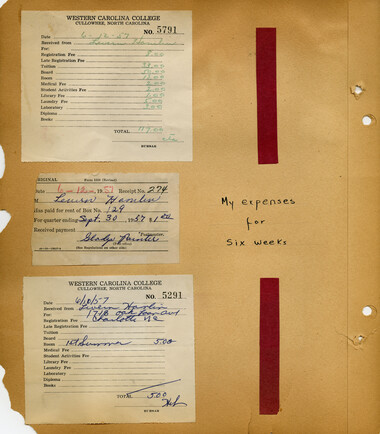

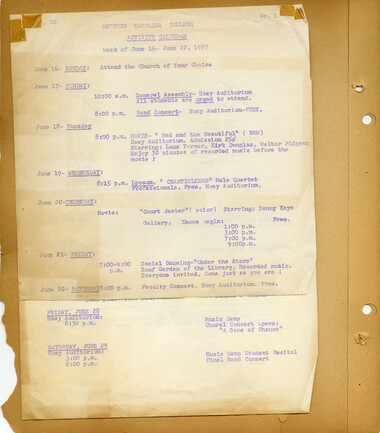

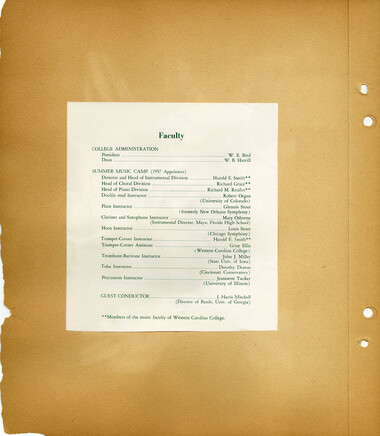

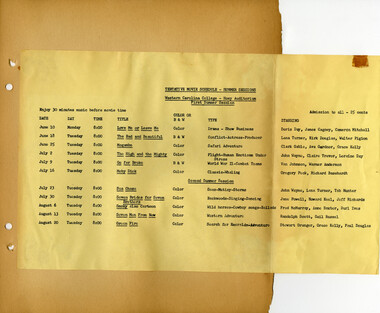

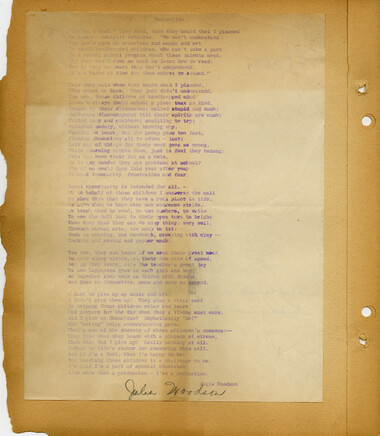

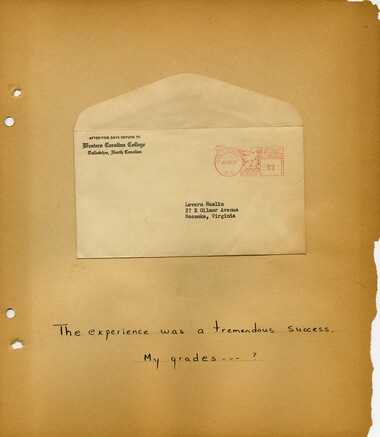

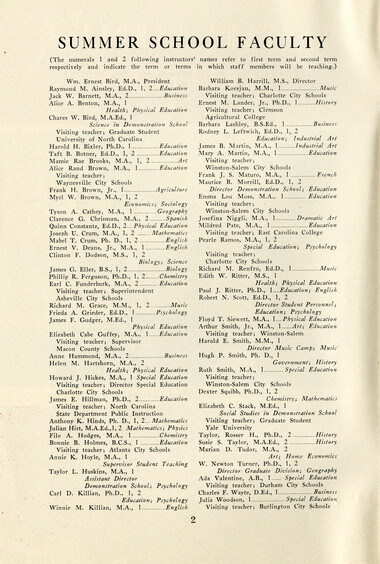

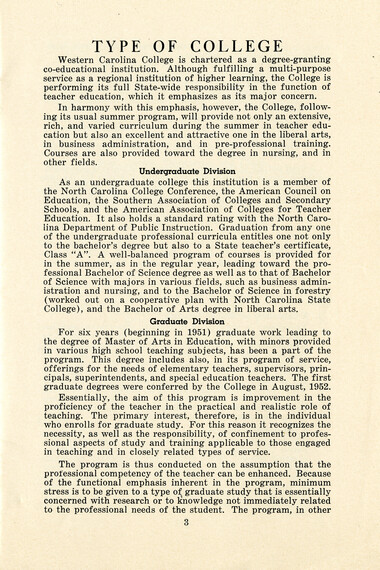

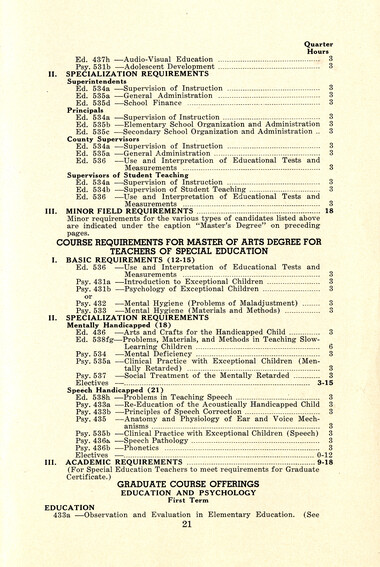

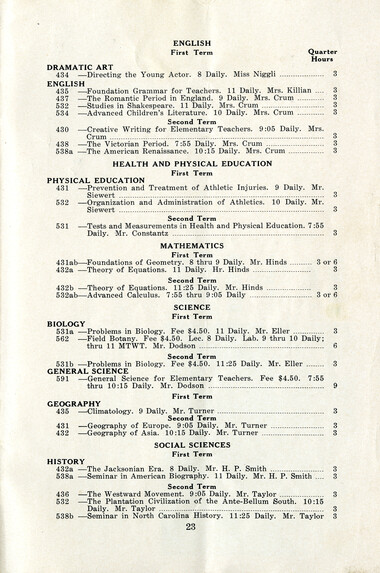

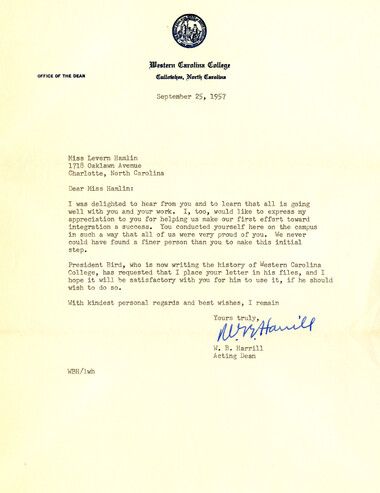

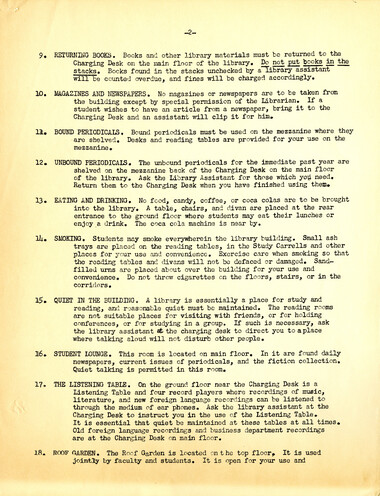

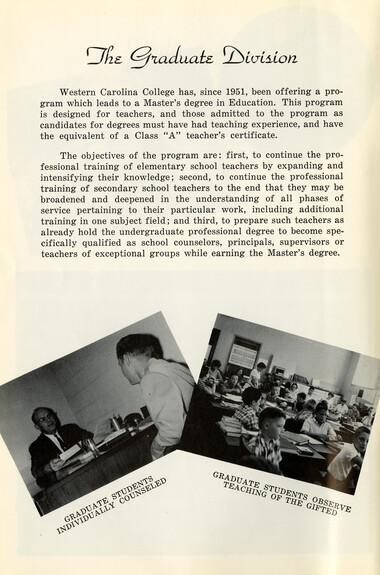

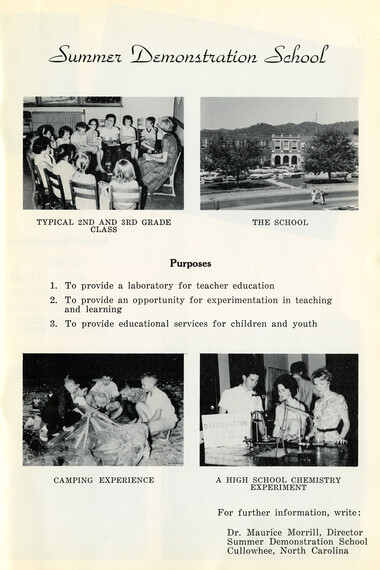

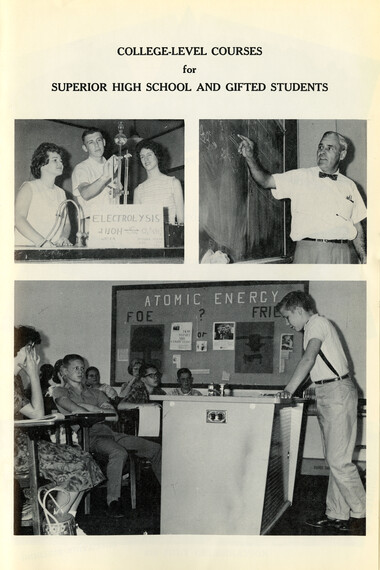

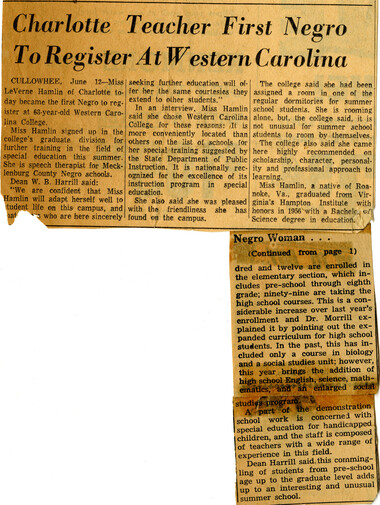

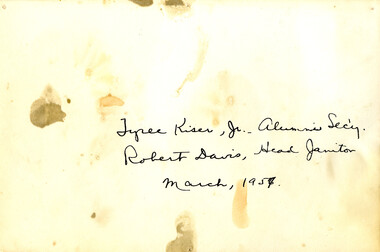

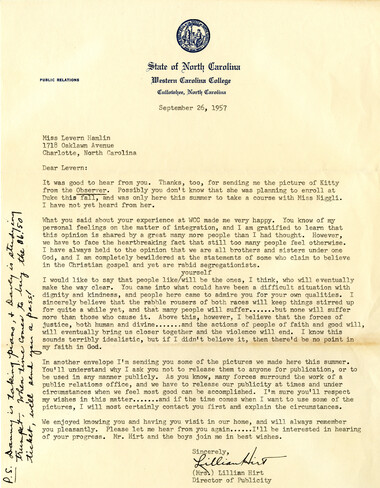

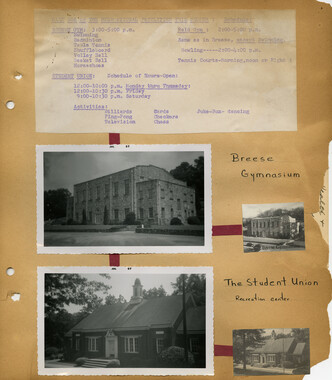

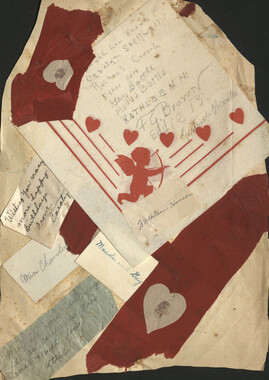

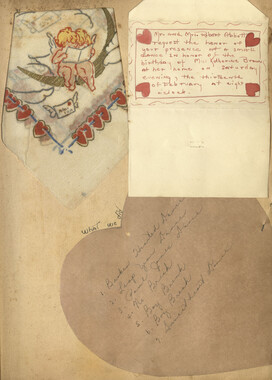

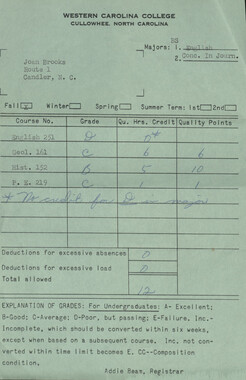

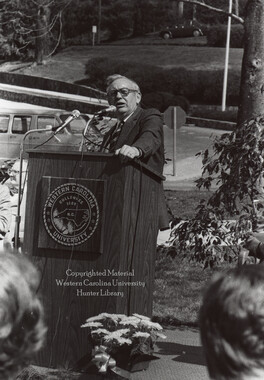

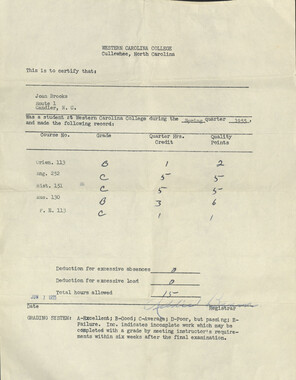

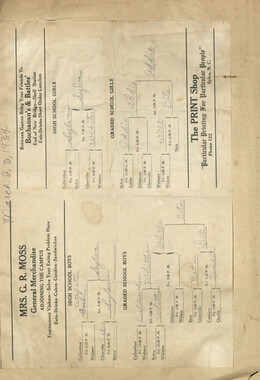

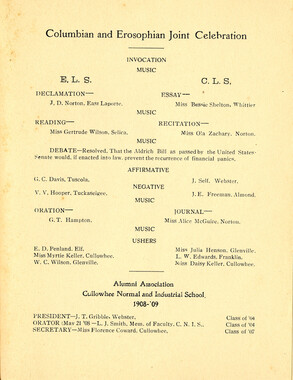

This 42-page scrapbook was put together by Levern Hamlin, a Roanoke, Virginia native who moved to Cullowhee, North Carolina in 1957 to attend Western Carolina College. Levern Hamlin was not only the first African American to attend Western Carolina College but the first African American admitted to a North Carolina state college. As a speech therapist practicing in Charlotte, North Carolina, Hamlin decided to further her training in special education through the college’s graduate division. The scrapbook begins with Hamlin’s account of her arrival at WCC on June 11, 1957 and includes numerous clippings describing the significance of her enrollment. The scrapbook contains entries from her summer semester at WCC extending to July 20th, 1957 when she arrived back at her home in Virginia. Hamlin had previously attained a Bachelor of Science degree in education from Virginia’s Hampton Institute in 1956. Also included are pamphlets and clippings at the end of the scrapbook.

-