Western Carolina University (21)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- George Masa Collection (137)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2900)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (422)

- Horace Kephart (973)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (316)

- Picturing Appalachia (6797)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (153)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1463)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (67)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

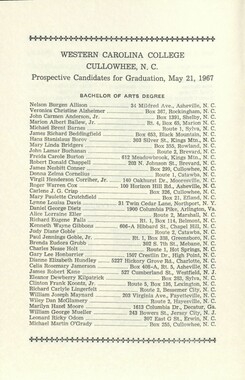

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (2008)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2959)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1944)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (195)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1680)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (556)

- Graham County (N.C.) (238)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (525)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3573)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4919)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (35)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (13)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (421)

- Madison County (N.C.) (216)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (135)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (982)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (78)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2185)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (86)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (192)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (3)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Digital Moving Image Formats (2)

- Drawings (visual Works) (185)

- Envelopes (101)

- Exhibitions (events) (1)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

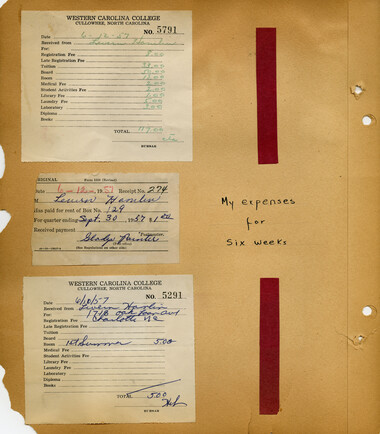

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (817)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1045)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (6090)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Notebooks (8)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (6)

- Portraits (4568)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (181)

- Publications (documents) (2444)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Relief Prints (26)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (1)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (18)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (324)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (462)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1482)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1923)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (190)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (111)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (2012)

- Dams (108)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (63)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1197)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (46)

- Landscape photography (25)

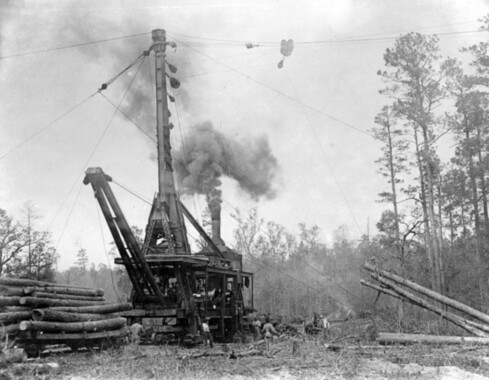

- Logging (119)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (9)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (72)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

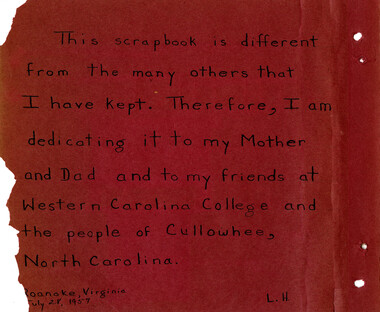

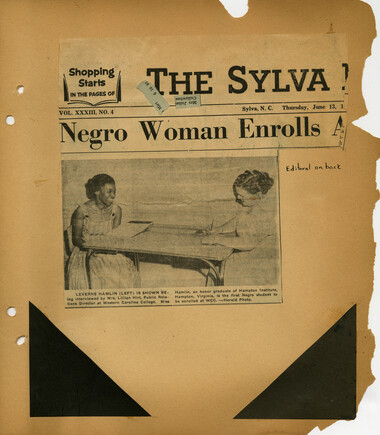

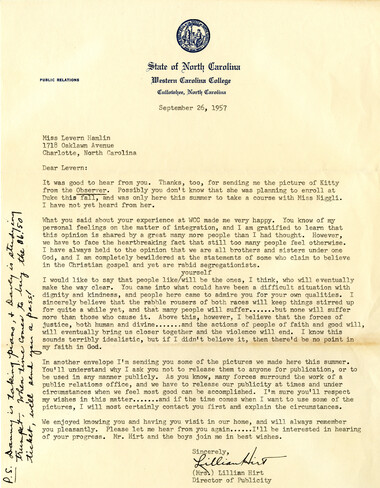

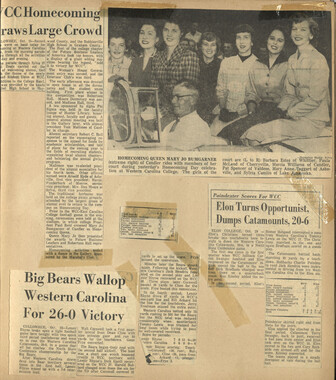

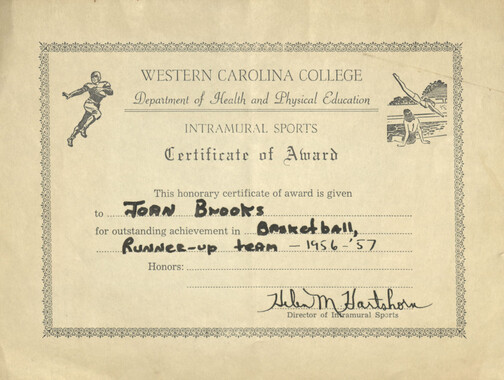

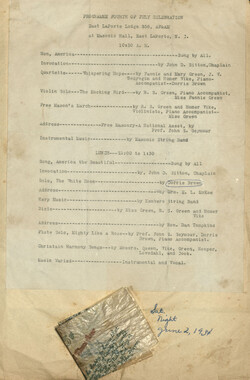

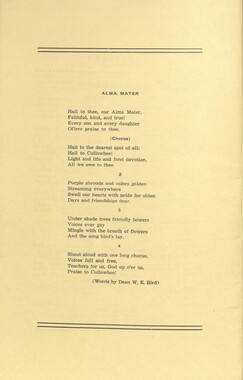

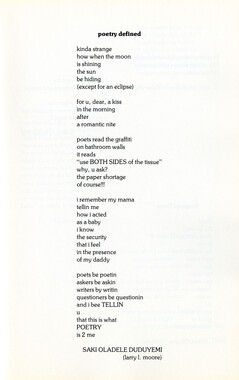

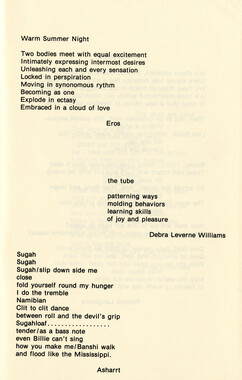

Levern Hamlin scrapbook

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

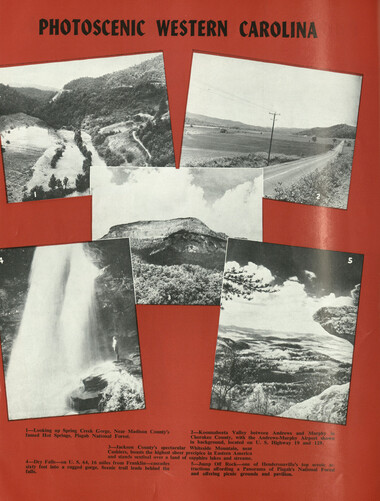

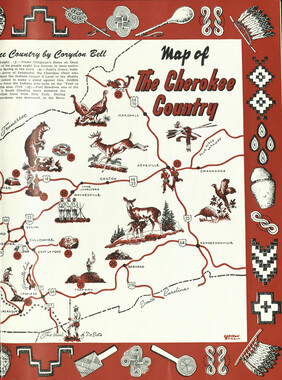

Alexander says some are more than 600 years old. Hemlocks—seven feet through—stand sentinel beside the spruce. Birch forms a canopy below tips of the hemlocks and then rhododendron—25 feet tall—makes an impenetrable jungle. It is possible to walk on top of the shrubs in spots but impossible to walk through the wilderness and difficult to crawl. The sun never shines on some of the ground. Twelve hours away is Washington. And yet here in the 20th century is a partly unexplored region where 6,000-foot peaks poke their noses through clouds and shield birds and animals that never saw man. The mountains hide the jungle's virgin beauty from all but the adventurous. One spot of the wilderness changes colors like a chameleon during seasons. Anemones turn the fastness into a glittering white carpet in the spring and then violets and trilliums sprinkle the carpet with clusters of blue and yellow. Azalea comes next and rhododendron and laurel convert the landscape into a mad confusion of mauve, purple, pink and white. Then there are asters, daises and more than 100 other flowers. Animals that scientists say live nowhere else south of Canada hide in the crags. Bear and deer roam the forests in peace. There is a heavy stillness about the jungle that makes men talk in whispers. It's just like nature made it, and Uncle Sam intends to keep it that way. . . . The foregoing was written some twenty years ago while I was a roving reporter for The Associated Press. Since then, scientists and explorers have tapped many of the mountains' mysteries and charted much of their fastnesses. Yet, the beauty remains unspoiled. Lying astride the North Carolina-Tennessee border, the Great Smokies form the greatest mountain mass east of the Black Hills of South Dakota. Scientists say it is one of the oldest land areas on earth. The Great Smokies, for thirty-six consecutive miles in the park, are more than 5,000 feet in altitude. Sixteen of the peaks are more than 6,000 feet high. Wiley Oakley, "the Roamin' Man of the Mountains," says the peaks are so tall they have to fold over at night to keep from bumping the stars. These are the mountains that balked empire builders for two hundred years. They stood apart as a high, far-off land of mystery bathed in purple, smoky haze. The Cherokee gave them their picturesque name, and there are some who say when the haze is thick that The Great Chief Above is smoking His pipe of peace. A modern transmountain highway knifes through the heart of the 461,000-acre domain and 675 miles of trails lead to the summits, and to the depths of the forest. There are established camp grounds in the Park, and the Appalachian (Maine-to-Georgia) Trail traverses much of the area, providing lean-to-shelters. Six hundred miles of trout stream are open to fishing under Park regulations. In addition to preserving the works of nature through the Park, the government also is attempting to preserve the lore of the Great Smokies. Even in the beginning, the government realized that the Park presented an opportunity to preserve frontier conditions of a century ago. Several typical mountain communities remained intact within the Park boundaries and they were considered valuable outdoor exhibits in a proposed "museum of mountain culture." With these as a basis, officials set out to erect the museum. The project has been slow in developing but it is expected to be completed within a few years. Already large collections of household goods, tools, farm equipment, weapons—chiefly primitive and hand- wrought—have been assembled. Many of them are on display at the Pioneer Museum just above the village of Cherokee. Only recently a pioneer mountain homestead has been relocated on the grounds of Pioneer Museum which is open to the public. Several deserted log cabins have been moved to the banks of the Mingus Creek, a few miles above the museum. This is to be one of the pioneer colonies in the park. The customs of the mountaineer, with his squirrel gun for "feudin' and his primitive methods of weaving, tanning, blacksmithing and cobbing, virtually unchanged in 150 years, will be collected and preserved. When the educational program of the park is inaugurated there will be folk festivals to acquaint visitors with the customs of the mountains. The arts and crafts already are being protected and encouraged. Families in and near the park are plying the handicrafts trades handed down from colonial days. The products are offered for sale to park visitors. These products include homespun, bedspreads, hooked rugs and wood carvings. The National Park Service realizes the great asset afforded the park by the presence of the rough-hewn cabin, the picturesque highlander, and the folk-songs and ballads brought by the pioneers from England and Scotland. One of the purposes of establishing the park was to preserve the colorful and typical features of mountain life, and the government now is well along with its program to keep this region just as it was in the past. .^A L i .^|^^j|g^^£^,7. <*? ■^tSsS ^JvlR/ a#5 3£to*;fo'&^^^

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

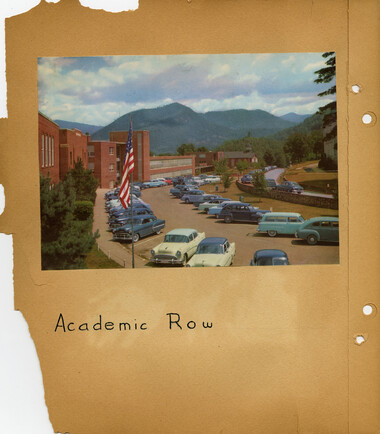

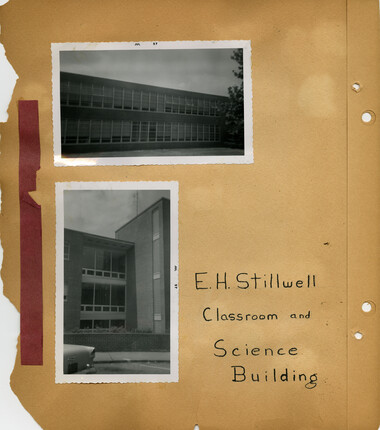

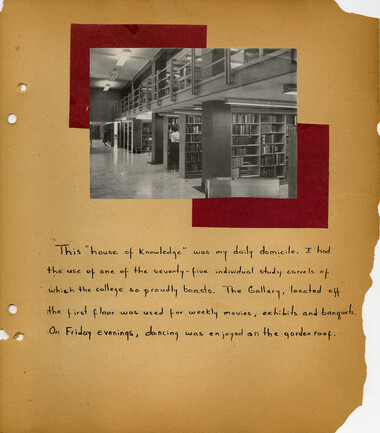

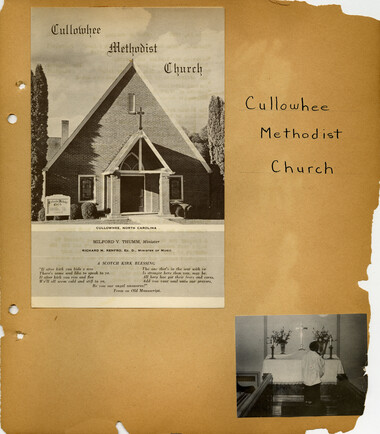

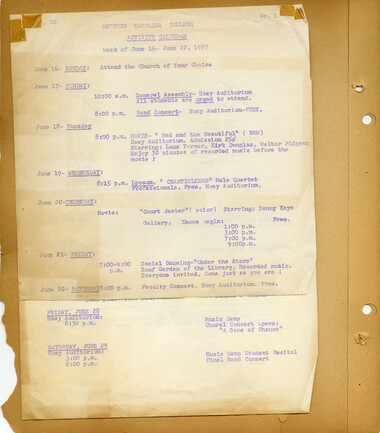

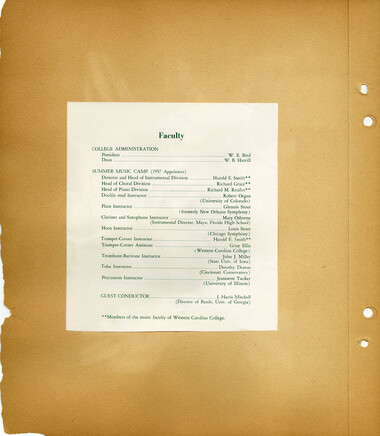

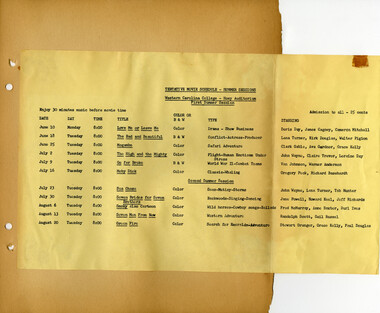

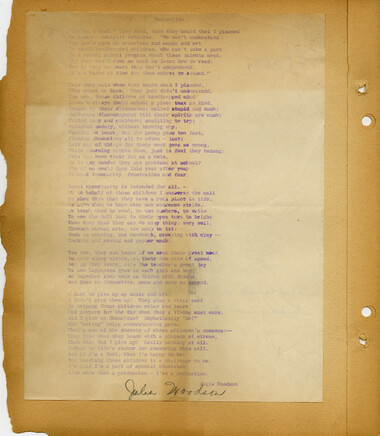

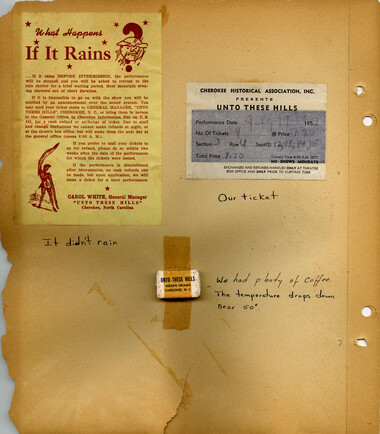

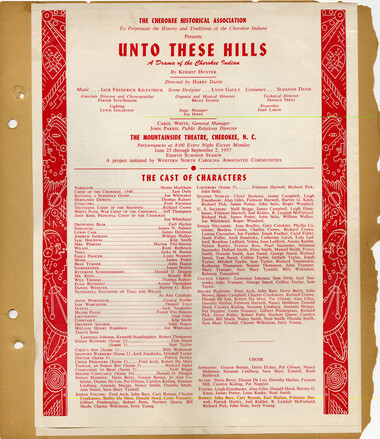

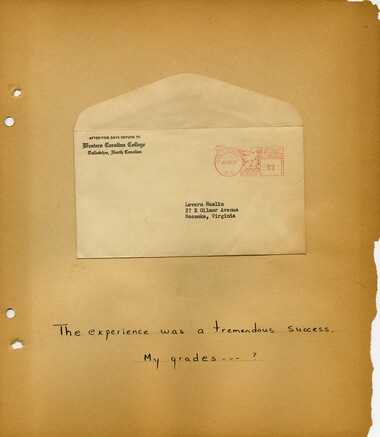

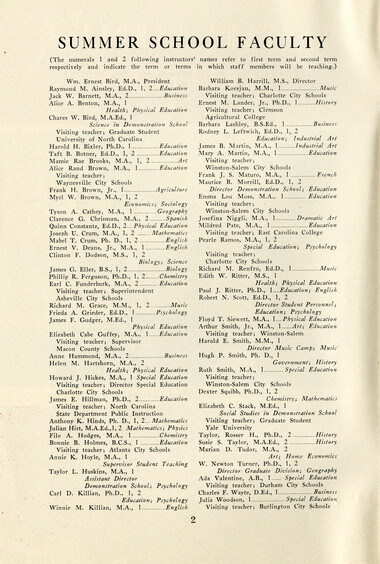

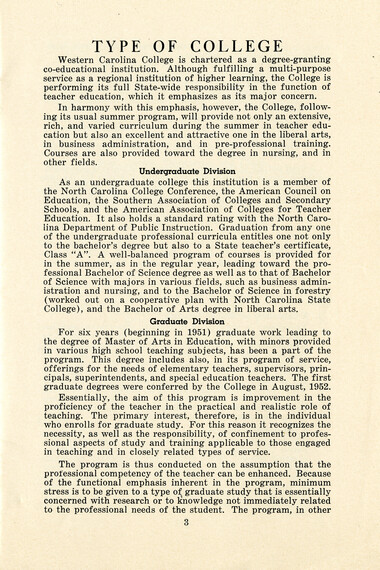

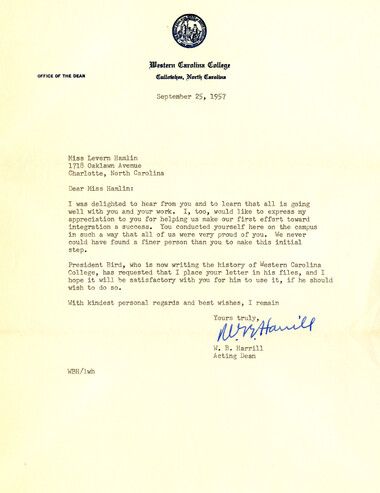

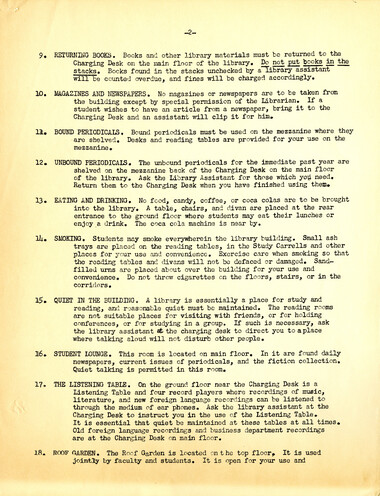

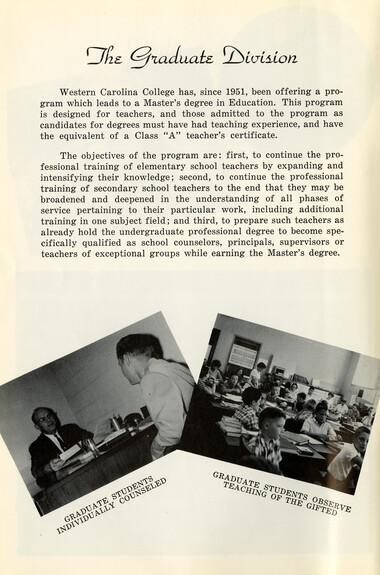

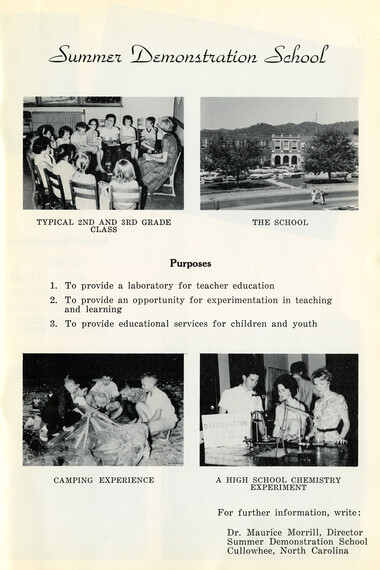

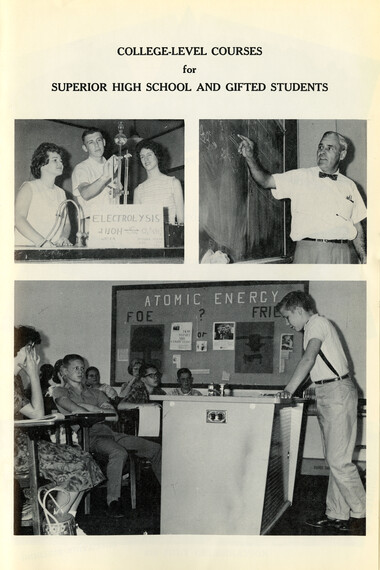

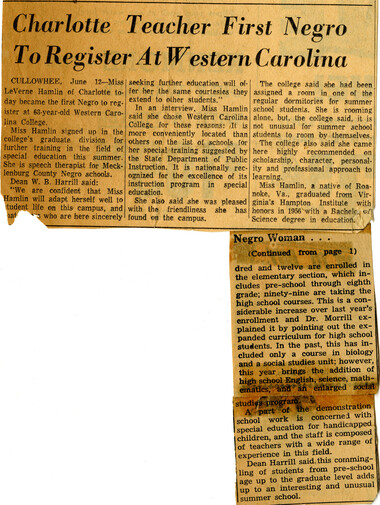

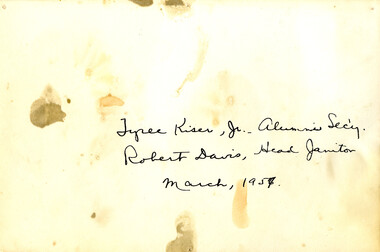

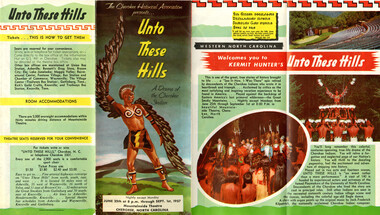

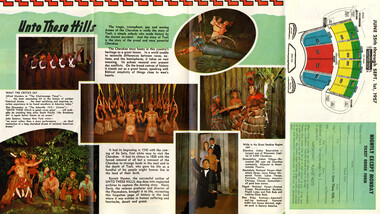

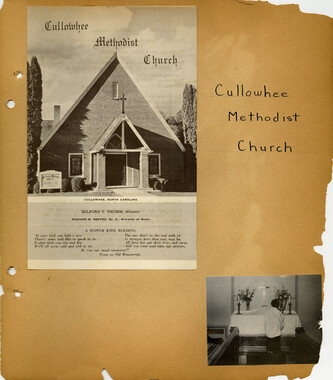

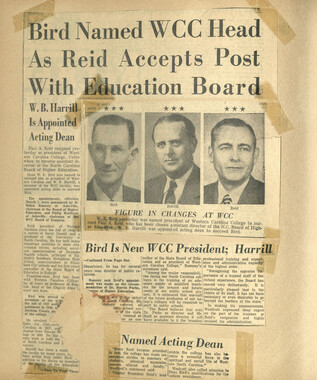

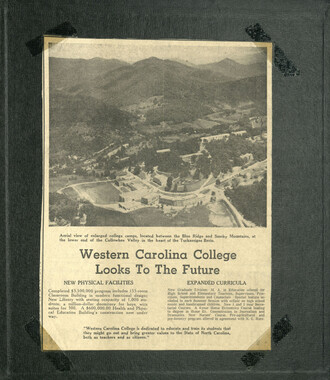

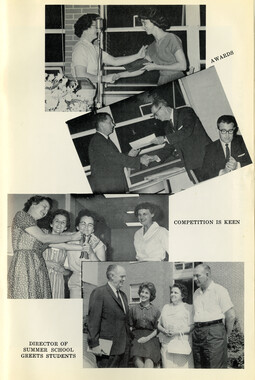

This 42-page scrapbook was put together by Levern Hamlin, a Roanoke, Virginia native who moved to Cullowhee, North Carolina in 1957 to attend Western Carolina College. Levern Hamlin was not only the first African American to attend Western Carolina College but the first African American admitted to a North Carolina state college. As a speech therapist practicing in Charlotte, North Carolina, Hamlin decided to further her training in special education through the college’s graduate division. The scrapbook begins with Hamlin’s account of her arrival at WCC on June 11, 1957 and includes numerous clippings describing the significance of her enrollment. The scrapbook contains entries from her summer semester at WCC extending to July 20th, 1957 when she arrived back at her home in Virginia. Hamlin had previously attained a Bachelor of Science degree in education from Virginia’s Hampton Institute in 1956. Also included are pamphlets and clippings at the end of the scrapbook.

-