Western Carolina University (8)

View all

- Cherokee Traditions (38)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (1)

- Journeys Through Jackson (37)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (5)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (24)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (4)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (3)

- Western Carolina University Publications (83)

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (0)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (0)

- Craft Revival (0)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (0)

- Horace Kephart (0)

- Picturing Appalachia (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (0)

- Travel Western North Carolina (0)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (0)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (0)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (0)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (0)

University of North Carolina Asheville (0)

View all

- Faces of Asheville (0)

- Forestry in Western North Carolina (0)

- Grove Park Inn Photograph Collection (0)

- Isaiah Rice Photograph Collection (0)

- Morse Family Chimney Rock Park Collection (0)

- Picturing Asheville and Western North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Western Carolina University (83)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (12)

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association (0)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (0)

- Berry, Walter (0)

- Brasstown Carvers (0)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (0)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (0)

- Champion Fibre Company (0)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (0)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Crowe, Amanda (0)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (0)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (0)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (0)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (0)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (0)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (0)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (0)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (0)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (0)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (0)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (0)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (0)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (0)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (0)

- North Carolina Park Commission (0)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (0)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (0)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Roberts, Vivienne (0)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (0)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (0)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (0)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (0)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (0)

- Stearns, I. K. (0)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (0)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (0)

- USFS (0)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (0)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (0)

- Western Carolina College (0)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (0)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (0)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (0)

- Williams, Isadora (0)

- 1700s (1)

- 1860s (1)

- 1900s (1)

- 1920s (1)

- 1940s (3)

- 1950s (9)

- 1960s (14)

- 1970s (18)

- 1980s (20)

- 1990s (20)

- 2000s (32)

- 2010s (214)

- 2020s (21)

- 1600s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 1890s (0)

- 1910s (0)

- 1930s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (15)

- Asheville (N.C.) (2)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (4)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (155)

- Macon County (N.C.) (2)

- Qualla Boundary (38)

- Swain County (N.C.) (1)

- Avery County (N.C.) (0)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (0)

- Clay County (N.C.) (0)

- Graham County (N.C.) (0)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (0)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (0)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Madison County (N.C.) (0)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (0)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (0)

- Polk County (N.C.) (0)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (0)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (0)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (1)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (3)

- Interviews (62)

- Maps (documents) (1)

- Newsletters (120)

- Periodicals (37)

- Photographs (6)

- Publications (documents) (1)

- Sound Recordings (70)

- Specimens (4)

- Transcripts (48)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (16)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Manuscripts (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Personal Narratives (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Map Collection (1)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (83)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (24)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (15)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- African Americans (2)

- Cherokee art (9)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (3)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (1)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (1)

- Education (1)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (1)

- Gender nonconformity (3)

- Maps (1)

- Storytelling (2)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Artisans (0)

- Cherokee women (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Floods (0)

- Folk music (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Hunting (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Mines and mineral resources (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- School integration -- Southern States (0)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- Slavery (0)

- Sports (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- World War, 1939-1945 (0)

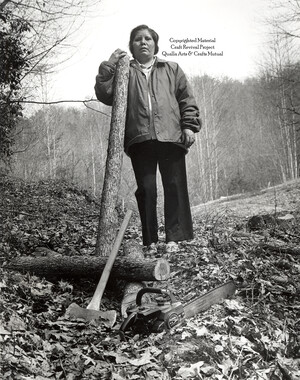

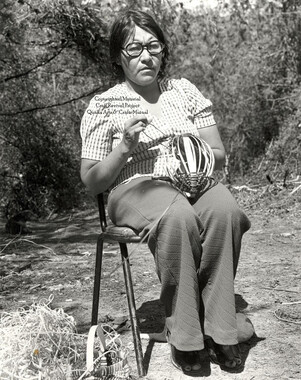

Joel Queen: Cherokee Artist and Potter

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

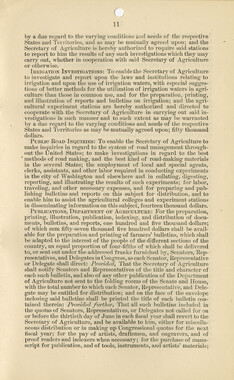

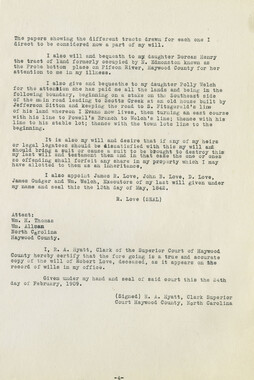

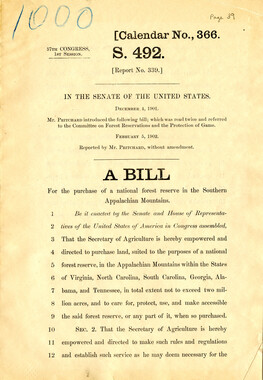

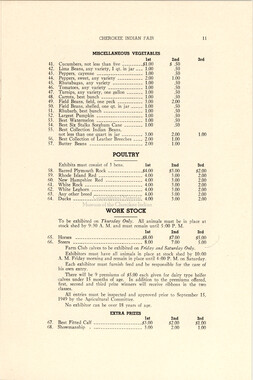

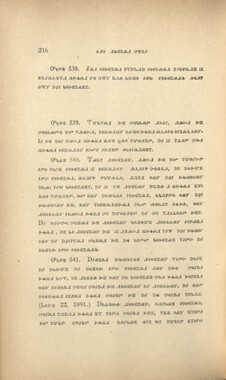

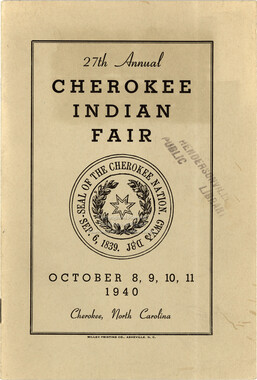

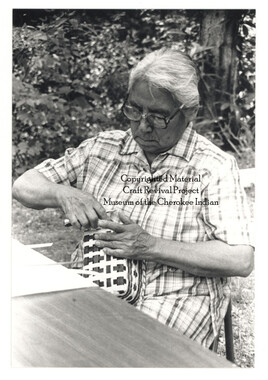

Joel Queen Transcript Summer, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 1 START OF JOEL QUEEN David Brewin: So Joel is a real well known potter. Joel how did you get into pottery? Joel Queen: It’s been a very storied tradition, I originally didn’t start out in pottery, I originally started out as a basket maker. My grandmother Martha Bard she taught me how to make place mats and small baskets when I was about five years old. And I quit making them. After she showed me how to do it I didn’t have any interest in it. Then I got into first grade. Eileen Stanpard taught me how to do bead work on a loom, I thought that was pretty interesting. And I was always hyperactive so I was jumping from one thing to another always continually going and going and going. Well Dee Smith taught me how to play around in paint a little bit and play around in clay a little bit and I really didn’t start taking off in as you would say a professional field until I got into high school. And I had Patricia Kimbrell’s class. She used to be an art teacher that Cherokee had before they went and made the pro Indian movement where all teachers that taught art had to be of Cherokee decent. Well she had more of an influence on me than anybody else. She taught me how to throw pots on a wheel. She taught me how to slab build pots, she also taught me how to work leather, she taught me how to paint oil and watercolor both. She taught me how to do silversmithing. She taught me how to cut my own gem stones down. I can just keep naming off a list of what this lady helped me with. And in the meantime I also started running a printing press for the high school down in the graphics department. And I kind of put my artwork to the side at the time. And I went to work at the boys’ club running the big four colored offsets. But [inaudible] my printing days, I loved to print books, especially hand made books. But after being in the commercial field you don’t really want to go back to doing that again. And that was a love that was lost. But I started working at the Indian village about the age of 18, 19 in between college courses and I picked up a pocket knife and I started whittling around and I started carving things out like making little miniature corn pounders and carved my first pipe when I was there. It just accelerated from there. I knew that my family was potters on the Bigmeat sides, but I never had really any intention of going in to it. And me and [inaudible] Standing [inaudible] was talking one day when I was down at the boys’ club and he goes you know if a man was to take about five years and sit down and learn how to master clay he could actually write his own ticket because nobody around here is producing a good quality pot. It’s all the Indian village stuff. It’s all Bigmeat stuff and I don’t have nothing against the Bigmeat family, the Bigmeats, they are my family, but they also, they threw on the wheel a lot so they were making the pots and just mass producing them. Nobody was sitting down and making a large quality pottery that was different, and that’s what I done. I sat down and I started experimenting. The first two pots that were made was made with me and Louise Maney or Louise Bigmeat. John Henry threw them, I polished them and him and Louise fired them and then I went back and designed them. I still have that first pot in the gallery today. I’ve got it back from them. The second pot I’ve done with them, somebody stole out of their gallery and that was a shame because if I ever find it I know what it looks like. It’s etched in my memory. So nobody is going to Joel Queen Transcript Summer, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 2 get away with putting that on a market without me seeing it and finding out that it was stolen. It’s just been a constant evolution of working. You have to be prolific at it. You can’t just do it one day then stop and expect to be at the same place the next day. You have to continue working with it, working with it and working with it. And I work in a lot of different mediums too, so if I get bored at one thing then I’ll jump to something else and plus it’s allowed me to continue to sell on a market too. If pottery slows down then I can always go back to stonework and if stone work slowed down then I could go to making pipes or some sort of other work. That will continue to allow me to bring income into the family. And yeah, it does get difficult and it gets to the point to where I just want to stop. Almost to the point to where nobody appreciates it anymore. They see all this that’s been going on. And they say well Joel is going to continue to do it, why should we have to learn it. I’m only one person and there is a lot to learn out there and I’ll never quit learning. And if somebody says that they are the best at what they do, they’re lying to you, because there is always somebody out there better. Somebody else out there that’s spent just a little bit more time, perfecting the techniques just a little bit more than you. So whenever they say I’m the best at this, I’m the best at that, don’t let ‘em kid you they’re not. Because there’s always somebody better. I found that out. I like competing, I like traveling, I like showing my work across the United States. The co-op has been a good source, or an income source and they’re doing a really good job, but they forgot one thing. They forgot that there’s more out there than just traditional work. There is a whole realm of abstract and there’s a whole realm of basically modern work that is not being showed because they won’t have that in their shop. They won’t have that other aspect of what is going on. And for a culture to evolve you have to be able to evolve along with the art work and they’ve not done that. They want to stick with their baskets, they want to stick with their pots and up until 5 years ago I couldn’t even show a nude on reservation. And I remember [inaudible] Cruise telling me one time that I couldn’t show a stone carving because it was of a naked lady during the fall festival. She said I think that’s pushing the edge just a little bit too much. Well a couple of years later there was one that actually made it in there, but it wasn't what she thought it was. It looked like something else, but if a person was knew what they are looking at it was a naked lady. So eventually that wall was broken down. But the co-op is missing out on a lot of modern art that could be selling. People love collecting traditional Cherokee art, but they also love collecting new stuff. This is my daughter’s work. I don’t think anybody around here would understand it, but I could take it out west and hell it would sell in a heart beat. But you’re having to walk that fine line here, how far can I push Cherokee art before they say it’s gone too far. And that line should never have been drawn in the ground to begin with. DB: Why do you think there’s a difference between the western tribes and their view of taking things out more to the limit than here? JQ: Well after WWII you have the Avant Garde movement out of Europe that were expecting all this. And they took the western artists and kind of babysitted them I would Joel Queen Transcript Summer, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 3 say into the modern world and accepted difference, and accepted change. While preserving the past, they also allowed for the future to evolve. And that’s something that has not happened here. There is a lot of modern designs that I could produce that people just wouldn't accept here. And there’s different ways to produce wood pieces that don’t have to be a bear or don’t have to be a squirrel or don’t have to be a fox. It could just be a square block of wood that’s finished really nicely. It’s all according to how you look at it. Everything around you is art, it just depends on who is looking at it. And with the western people and the way they’ve done it, they’ve allowed for that exposure for that growth to take place. Where here, very few of us are pushing that for that growth to take place. They would rather see and Indian village style pot that they could buy for $14 than they would rather see a nice, shiny, black pot that sells for $14,000. And there’s a big difference. And but at the same time, it takes all kinds. You can’t just say, well you need to bring your style of work up, you need to do this you need to do that. Some people are just happy with getting by. I’m not happy with getting by. I wanted to leave my mark on this earth a long time ago. And through my art work I’ve done that and I’m going to continue to do that. And whether they like some of the stuff I produce that is completely up to them and if they don’t then I’m not the one being left behind. I’m not going to hold anything back, especially when it comes to teaching my kids. If they want to do something that is completely different then fine. I’m not going to stick to them and make them say you have to learn to do traditional Cherokee pottery, because in all reality I’m the only true traditional potter that there is. I’m the only one that digs the clay, I’m the only one that pit fires it, I’m the only one that claw stamps it and everything else, but yet I’m not a traditional potter. So it’s all kinds of things that are going on here. You could buy a bag of Lizella from Georgia and bring it up here and make a pot and fire it in a kiln and say yeah, it’s a traditional pot. And in no way, form or shape is it a traditional pot. Because you didn’t dig the clay, you didn’t pit fire it, you put it in a big long kiln with a roof, or a chimney sticking out of it and heat it up slowly, you didn’t claw stamp it, you may have incised it a little bit, but you still stuck it inside of a wood kiln. And there is nobody around here doing a true, tradition pit fire besides me. And I don’t give a damn who knows it, I don’t care who I piss off about it. So that’s the bottom line, if you’re going to holler tradition then show me tradition. DB: This brings an interesting thing, because the whole series of interviews we have been doing have been traditional craft people and keeping the tradition alive, passing on generations. You’re just as much a traditionalist and according to you even more so than most. Are you passing this down? JQ: If they want to learn. What they want to learn I will teach them I’m not going to ram it down their throat, some people just aren’t meant to play in clay, some people aren’t meant to be a stone carver, but as far as if you’re going to be a traditionalist, then be a traditionalist, don’t half ass be one. Don’t tell me that you’re a traditionalist and buy your clay somewhere else. Or you use a Japanese style kiln to fire it. If you’re going to be a traditionalist and you can say this is a truly traditional Cherokee pot, then I want to see it pit fired and there ain't nobody around here capable of doing that if there is there’s very few of them. And the price on a true pit fired pot is up there. The bigger they get the harder they are to fire. And the Indian village has a little square kiln sitting out back there Joel Queen Transcript Summer, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 4 that they fire out of. Several other people have little kilns that they fire out of wood fired kilns. None of them have actually sat down and built a pit fire and say this is a true traditional pit fired pot. DB: Out there by your studio is that where you pit is? JQ: I have different things. I have 55 pound barrels that I’ve used to produce the blackware with, but to do a traditional pot, I’ll have to dig a pit and line it and burn it out and dry it and everything else. Usually with a true pit you need to keep it covered because the moisture is going to soak back up and it’s going to cause problems. Usually we line it with broken shards and stuff like that, but most of the time nobody wants to pay for a true traditional pot. Cost wise because there ain’t no telling how many you’re going to lose to get one out and you have to be careful with the wind blowing the wrong way you have to be careful with the clay body that you’re using. If the pot is too thin it’ll crack if it is too thick it’ll crack. If the rim is not supported by the [fold down] it'll crack. There’s just a lot of things that will go wrong. So when you see me slap a thousand dollar price on a pit fired piece that is this big around 6 or 7 inches it’s because I’ve actually took in that pot from beginning to end and built a true, traditional pot out of it that is capable of holding water and cooking your lunch in. And it’s just, I don’t know if you’re going to be quote unquote this traditionalist then be a traditionalist. Don’t half ass do it, don’t cheat one way and then say it’s going to be something else. It would be better just to say I’m a Cherokee potter and leave it at that then to say I’m a traditional Cherokee potter. Because that word traditional has got a lot of meaning behind it. A lot more than what they give it credit for. And that’s my biggest problem and I guess that’s why people consider me such an asshole about it. If you want to do it do it the right way, if not just tell them, look I am a Cherokee potter, I am not a traditionalist, but I am a Cherokee potter. I mean I don't consider myself a traditionalist. I do too many different styles. I mean I’ll fire from cone 10’s to Japanese style raku to the reduction style of blackware, to the traditional pit fired stuff. It’s just a matter of what I’m in the mood for. But if you want to say that you’re a traditionalist, just don’t half way be there. DB: You see any change like moving toward your philosophy of it, you can be traditional, but you can move forward too? JQ: I would like to see more change, it’s not moving fast enough for me. We’re being left behind and it feels like I’ve carried a lot of weight on my shoulder for the past ten years to get Cherokee art work where it’s at. Nobody here is going to Santa Fe and done what I’ve done to put Cherokee art back on the map. And oh sure they’re fine and dandy, they’re happy with you when you do it, but that’s it, there’s no respect out of it. There’s no … I guess there’s really no gratitude in it. They’re just like, oh he done something really nice for us, okay let’s do something else. But yet, I really don’t know how to put this into words, they are looking so forward to the future they forgot where they came from. And when you forget the past, you’re doomed to repeat it and that sounds so cliché but it is happening again. Honestly it is happening again. DB: Why? Joel Queen Transcript Summer, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 5 JQ: $640 million for a casino in the middle of a bad economy. Tell me we’re not going to lose our ass. There is nothing if the Pequots are laying people off and they’ve got the world’s largest casino something is the matter. And it wasn’t the time to build a casino that large. I think our casino is laying people off from what I understand. I don’t think it is going to… I don’t think it’s going to be the big windfall that they were predicting. Business wise I think it was a bad decision. If it works more power to them, but in all reality every bit of my business sense is saying that it’s not going to make it. I mean hell I’m having a hard time making it out here on the side of the road and I don’t have half the overhead they have. So. DB: So you’ve seen the change in your business because of this economy? JQ: Yeah, I thought we was going to make it through this, but I’m beginning to have my doubts. I am very, very seriously beginning to have my doubts on that. And I mean we’ve dropped the prices, we’ve done everything we possibly can besides actually give it away. I don’t know, I just don’t, I don’t see how unless something changes here within the next 6 months, there’s going to be a lot of people folding. Luckily I’m one of those that have a job that can follow money into different areas. I’m not going to lose my property over it, I mean hell at some point in time the property is going to go back up. I don’t know how long this job is going to last. But it’s going to do a lot of new things, it’ll I think we’ll make it work. DB: Now this, we’ll get more pictures of this school we’re at right now. Do you teach all the classes here? JQ: Uh, right now I’m teaching about 90% of them. This is the summer, summer courses are in independent study. The students come in with a proposal, tell me what they want to do and then they fulfill it as they go along. Not only do we teach traditional Cherokee stuff, stone carving, basket making, two and three dimensional design, art history, but we also allow them the freedom to express themselves in the more contemporary art worlds. They don’t have to just set here and carve stone all day, like the lady sitting back there, she’s making body cast out of papier-mâché and she’s wanting to do a wall of [them] that was her project for the summer. Amelia is wanting to build small sculptures to where she can go to the art market and set up in OACA booth and sell her work. So it’s a good opportunity to work, and it’s a good opportunity to share with what I know with these people and allow them to expand their horizons with what they want to do, because there’s not been any female stone carvers since Amanda Crowe died and I’ve got three of them coming out now. And this is their second semester of working in stone. So they’re taking off they’re doing fine. There are really a lot of good artists on the reservation that just need a chance to open up. DB: Do you feel that this place around right now might be the opportunity for your vision and goals and moving the art into the 21st century? Joel Queen Transcript Summer, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 6 JQ: I hope so. I hope so. I can’t have a nude model class here, they’ve already made that very clear. It has the opportunity to open up a lot of people’s eyes to let them see what actually can be done with Cherokee art. Cherokee art just don’t have to be a basket. It can be basically anything. It can be a body painting. It can be basically a light show. It just don’t have to be something that is functional, or something or another that you have to split the basket, or split the cane to make a basket. Don’t get me wrong, I love river cane baskets, and I love everything that they mean, but has the design of the river cane basket changed in 500 years, it’s still the same thing. It’s… I would rather them be able to move, learn, learn what they are supposed to, learn the basic foundations and then expand upon it is what I’m trying to get to their heads, is what I’m trying to get them to do is the expanding part of it. I don’t want to hinder them in any way saying no you can’t do that, this is the way it’s supposed to be done. Because once you stop learning and once you stop learning from your students you might as well get out of the business. Because several of my students have showed me shortcuts and I’m a firm believer that there is no right way of doing anything as long as you come out in the end with same product and that’s basically the way I feel. The Indian village, I mean especially when they come to Cherokee pottery, they’ve produced a lot of good potters over the years, but they’ve also destroyed the market. I mean you have somebody sitting there making pots all day long and they’re only getting 6 and 7 dollars a piece for them. And then Clarence White turning them over for 12, 14 dollars. I haven’t made a 14 dollar pot since I started. I mean once, I got to sit down and figuring out what was in this, why should I make a pot for 14 dollars and it be this big around and me not make anything off of it. It’s taken a long time to break that mold. What I used to call Village pottery, there was some very good potters up there, Cora Wanita was one of the best, I actually own one of her pots, but she probably only got paid 6 dollars for it. And it was a damn shame that the historical association was allowed to get away with what they done. And yeah, the historical association helped preserve some of the arts, but at the same time they helped hold the arts back. They really, honestly hurt what Cherokee art really was supposed to be. And I’ve got one of the books around here somewhere, Arts and Crafts of the Cherokee. This is all Indian Village. That looks like my grandma’s baskets, but I think that’s Amanda, she probably got 6 dollars apiece for those pots. It’s literally ridiculous. Let me step outside and get this voicemail. But take a look at that, that’s what pisses me off. I mean it’s the what they were allowed to get by with it was ridiculous and I mean sure they got paid by the hour to sit there and yeah, they didn’t have to work all the time, but just to watch them to produce that work and them not get paid nothing for it, yeah, that really irritated me. To give you an idea, I’ve done a dough bowl for Clarence White, I carved him a… a dough bowl is in the shape of a turtle. It never even went to market, it went to his house and it’s sitting on his shelf the last time I seen it. I guess it’s still there his wife sold it all or something another. But it was it was ridiculous. Yeah, I’m controversial in my views sometimes, but I don’t care. DB: Well isn’t this what it takes to get things… JQ: Yeah, stir things up. And it’s sad that it has to be that way, but if you don’t, if you don’t learn then you get left behind. That’s the sad part of it, because we have a lot of talented people out there. Simply because their hands are being tied, saying no your work Joel Queen Transcript Summer, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 7 is not selling you have to do this. They quit doing what they truly love doing they actually that has been taken away from them. There is no reason why we couldn’t compete with the rest of the world, and we’ve just never been able to do it because we’ve been held back so long. Maybe this school will break it out and do good, I don’t know. I hope so anyway. DB: Well it seems like Darin is sort of picking up, he’s not afraid to try some new things. JQ: Turn it off. [inaudible] part came easy, that wasn’t the hard part. Breaking the molds down, what I thought was art and what was being accepted as art was the hard part I had to basically reinvent myself. I had to do things that I didn’t consider art. But once they were finished I could see the point why I had to do it. So and through Western Carolina, that allowed me to open my eyes up, it really did allow me to open my eyes up with what was going on and what was going on outside of here and yeah, it was an experience and it looks at… art has always came easy to me. Some people call it craft, some people call it art, we always had a big controversy over art had no place in business. Art has everything to do with business, because if you can’t sell it what is the use of making it and if you can’t make a living at it who is going to see it. There are a few people out there who do art simply for the sake of art, that don’t do anything with it besides give it away, but at the same time I mean I’ve got a family to feed, I have to be able to produce something that sells and I have to keep an eye on what the market is going and how things are going to be able to keep up with it. And if I can’t keep up with it then I’m falling behind. And once I added the teaching aspect to it, it made my job that much harder to be able to teach and to be able to do art at the same time. I’ve really slowed down a lot, that’s affected me, it’s not been the easiest thing in the world to do. But it’s getting there slowly. Just like today, when we get through I’m going to go set a banking account up and all kinds of stuff to be able to get everything done that needs to be done for this art market that is going to be set up. DB: When is the art market going to be set up? JQ: It’s the 2nd, 3rd and 4th of July. And it’s designed to show people around here what’s going on outside of here and allow them to compete against some of the best in the world, and if they can win here they can win anywhere. And that’s the point that I’ve been trying to get across to them, is that you need to be able to compete, you need to be able to refine your skills to where you are capable of competing elsewhere. To where you don’t go somewhere and get embarrassed by taking a half way done piece of work out. I’m a firm believer in having to be able to have a completed piece of work to show. Just don’t bring me one that’s half way done and expect to win because it’s not going to happen. But as a whole I’ve had a very good experience with it. Like I’ve said, I’ve taken my beatings and I’ve also given a few. So it’s been very interesting. It’s just I’m right now I’m just tired. I’m really tired, I’m really frustrated with the way things have been going and it’s one of them things that… I have to work through that. It’s just like anything else, you have to be able to work through your own personal problems to get to where you need to be. And I do find enjoyment working with my students and that’s what I’ll show you out here in a second, just come on out. Joel Queen Transcript Summer, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 8 END OF JOEL QUEEN INTERVIEW START OF TOUR OF OCONALUFTEE INSTITUTE FOR CULTURAL ARTS Filming at the Oconaluftee Institute for Cultural Arts OICA. David Brewin: Is she working as a craftsperson now? Joel Queen: She’s actually at Western Carolina working on a bachelor’s degree. Went on into art at Western Carolina. DB: Wow JQ: And you can see this stuff this is all first semester students. They are in the gallery with the students’ artwork. Camera zooms in on a stone carving that is a head with a face on one side and a bear on the other, maybe the person is carrying the bear. DB: Stone carving is really impressive. JQ: They’ve really done good for their first semester, I mean it’s really surprising. DB: So they would just come here and go to art school for a semester and then [inaudible] going on over here. Camera is focused on a stone carving of a bird looking at a nest in a tree. JQ: We offer an associates in art that will transfer to any North Carolina school [through an articulation agreement]. Showing pottery and small wall hanging weavings. A lot of them just want to know that they can do something else. One of the things that Dr. [Grow] was asking me when I took the job he goes can you teach these people how to make a living in two years. I said, “No I can’t.” I said, “I can teach them how to supplement their income in two years, I said but I cannot teach them how to make a living in two years.” So if they want to take two years and expect to make a living out of it they are going to have to really, really work hard. Showing more pottery. DB: Do you have students that are planning on making a living with this? JQ: Amelia is probably the best one we have right now, she is really wanting to push herself to get better to where she could actually probably make a living at it. A couple of the older students, Dianna and her mom could probably make a living at it if they really tried. Joel Queen Transcript Summer, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 9 DB: Do you have any of Amelia’s work in here? JQ: This is Amelia’s right here. Showing the stone carving of the face with bear. This is her piece. This is James, showing stone carving of a bird with tree and nest. See James has got some pretty good ideas he was going to build a bird’s nest into actually a piece of tree and this is her daughter’s Dianna’s. Showing a stone carving of an animal in a crouched position. DB: I like that side of it. JQ: Yeah. But Dianne is also the one that does all the weavings too. She does a lot more than just stone carving. DB: So you’ve actually got a loom here and everything. JQ: Yeah, we have full size looms back here. And this is the largest piece that she done. I actually would like to have this [inaudible] house itself. DB: That is nice. JQ: She can weave faster on a loom than I’ve ever seen anybody do, I mean she can [inaudible]. We have different teachers come in for that. We also had a Ramono Lawsey come in and talk to them about how to make placemats and baskets and stuff like that. You can see over here I’ve taught them how to make pottery and [inaudible]. They’ve really gotten good at that. DB: I’m interested in the blackware, did you bring that back you are one of the biggest proponents of that southwestern blackware. JQ: The Bigmeats were producing blackware and the blackware has been part of the southeastern style of pottery all along, it’s just nobody refined it. Nobody refined it and took it to the point that it did. I looked at Maria Martinez work and I look at Joseph [inaudible] work and I figured hell if they can do it I can do the same thing. DB: That’s right. JQ: And that’s where it came from was really looking at Joseph [inaudible] work and he was the biggest inspiration I had. DB: As part of your curriculum here, do you do anything with computer drawing stuff. JQ: We’re not set up for it right now. I would like to have a graphics art class here, but southwestern offers that, we don’t’ have it here. That’s something other that kind of holds us back because that’s where are a lot of people are moving toward is the graphic arts. It’s kind of as if we’re almost like a dying breed actually hands on people that tactually Joel Queen Transcript Summer, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 10 work with their hands. More advances they make with technology the less and less you’re going to see this type of stuff. It’s that’s going to be a shame. It really is going to be a shame. DB: I just like to use it from the standpoint of just getting, iron work had a lot of repeating designs and rather than draw every scroll it was handy from that standpoint. Can we look at some of the studios here. JQ: Yeah, let me grab some keys. DB: [inaudible] work here, being a metal worker. JQ: Yeah this is a workshop that that was done, they came in a showed [inaudible]. [inaudible] of course weaving [inaudible] DB: Well is that type of weaving does that have much to do with Cherokee crafts. JQ: Sometimes it did, some there was some traditional weavers that done that. This is the sculpture studio. It was wood carving, but it actually is considered a sculpture. It’s not very big. It’s unfortunately it’s not very big that’s why you see most of the ladies working outside. [inaudible] for some reason that doesn’t surprise me. You may have left hem in the car. We can always bust a window. DB: So they actually do the stone carving in here. JQ: Some of it, most of it is done on the back porch. See [inaudible] working with papier-mâché. We’ve got all the wheels set up, we’ve got them all set up kind of scattered out right now because they were all going hand building. They are going to be on the wheels next semester. So there will be a lot of aggravation. [inaudible] wheels they get kind of aggravated at it. DB: Do you know the Japanese potter Shoji Omota. JQ: Yep he’s [inaudible] over and over and over. These little jug piece tea cups. DB: Oh yeah. JQ: I just throw them all away. Kind of laid back they just sit here and do the work and they work and they work and they talk and they talk and they do some more talking and then they’ll do a little more work and they’ll do some talking and W I think you ought to do Amelia she is the epitome of [inaudible] DB: I have to keep your faces out of it because I didn’t bring enough permission forms. W So what are you filming. Joel Queen Transcript Summer, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 11 JQ: Might be able to work it with a little pocket knife just as easy. Be easy with it. Can always take it off but you can’t put it back on. There you go. Like that. DB: how long have you been working on that one. W hours wise, probably about 3[inaudible] coming and going. DB: Is this going to be your frame shop? JQ: Yeah, frames [inaudible] got a [inaudible] cuter in here. DB: Are you going to do lithographs and stuff like that. JQ: This is going to a letter press. [inaudible] actually print books, Cherokee books. DB: Wow. Oh this is the one I’ve heard about. JQ: Yeah, have [inaudible] print our own letters, be able to print Cherokee. DB: How would you see using that as turning into a sort of 21st century. JQ: It’s all a part of not forgetting where you came from [inaudible] really kind of fascinates me is people are just taking a grab them a piece of paper and just printing it. DB: Right JQ: It’s about [inaudible] set that much type to make two little pages then you have a whole different appreciation for it. that’s one page. DB: That’s a craft that is almost nonexistent now is the typesetter. JQ: Yeah, that’s why when I said that [inaudible] printing business, that’s why I really hated going back to that because [inaudible] kit took all the fun out of it. [inaudible] put that stuff up before you knock something over. DB: Is that your son? JQ: Yeah. DB: Is he a craftsman. JQ: He’s a good woodcarver, he’s going to be a [inaudible] if he don’t [inaudible]. He gets [inaudible] DB: Sounds like his daddy.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

In this video interview, Cherokee artist Joel Queen shares his interest in how art grows as culture grows. He aims to keep Cherokee tradition alive through the work of his hands. The transcript provided is an unedited version of the video.

-