Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (24)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- 1700s (1)

- 1860s (1)

- 1890s (1)

- 1900s (2)

- 1920s (2)

- 1930s (5)

- 1940s (12)

- 1950s (19)

- 1960s (35)

- 1970s (31)

- 1980s (16)

- 1990s (10)

- 2000s (20)

- 2010s (24)

- 2020s (4)

- 1600s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 1910s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (15)

- Asheville (N.C.) (11)

- Avery County (N.C.) (1)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (55)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (17)

- Clay County (N.C.) (2)

- Graham County (N.C.) (15)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (40)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (5)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (131)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (1)

- Macon County (N.C.) (17)

- Madison County (N.C.) (4)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (1)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (5)

- Polk County (N.C.) (3)

- Qualla Boundary (6)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (1)

- Swain County (N.C.) (30)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (1)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (3)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Interviews (314)

- Manuscripts (documents) (3)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (4)

- Sound Recordings (308)

- Transcripts (216)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newsletters (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Publications (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- African Americans (97)

- Artisans (5)

- Cherokee pottery (1)

- Cherokee women (1)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (4)

- Education (3)

- Floods (13)

- Folk music (3)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Hunting (1)

- Mines and mineral resources (2)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (2)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (2)

- Storytelling (3)

- World War, 1939-1945 (3)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Sound (308)

- StillImage (4)

- Text (219)

- MovingImage (0)

Interview with Willie Proctor

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

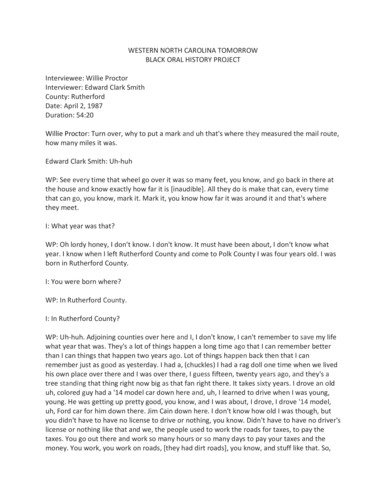

WESTERN NORTH CAROLINA TOMORROW BLACK ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Interviewee: Willie Proctor Interviewer: Edward Clark Smith County: Rutherford Date: April 2, 1987 Duration: 54:20 Willie Proctor: Turn over, why to put a mark and uh that's where they measured the mail route, how many miles it was. Edward Clark Smith: Uh-huh WP: See every time that wheel go over it was so many feet, you know, and go back in there at the house and know exactly how far it is [inaudible]. All they do is make that can, every time that can go, you know, mark it. Mark it, you know how far it was around it and that's where they meet. I: What year was that? WP: Oh lordy honey, I don't know. I don't know. It must have been about, I don't know what year. I know when I left Rutherford County and come to Polk County I was four years old. I was born in Rutherford County. I: You were born where? WP: In Rutherford County. I: In Rutherford County? WP: Uh-huh. Adjoining counties over here and I, I don't know, I can't remember to save my life what year that was. They's a lot of things happen a long time ago that I can remember better than I can things that happen two years ago. Lot of things happen back then that I can remember just as good as yesterday. I had a, (chuckles) I had a rag doll one time when we lived his own place over there and I was over there, I guess fifteen, twenty years ago, and they's a tree standing that thing right now big as that fan right there. It takes sixty years. I drove an old uh, colored guy had a '14 model car down here and, uh, I learned to drive when I was young, young. He was getting up pretty good, you know, and I was about, I drove, I drove '14 model, uh, Ford car for him down there. Jim Cain down here. I don't know how old I was though, but you didn't have to have no license to drive or nothing, you know. Didn't have to have no driver's license or nothing like that and we, the people used to work the roads for taxes, to pay the taxes. You go out there and work so many hours or so many days to pay your taxes and the money. You work, you work on roads, [they had dirt roads], you know, and stuff like that. So, it's uh, they's so many things that happen a long time ago that, uh, I don't know, people, uh, in fact I guess that I'd have to say that, see I raised twelve children and, well I raised my wife's daughter and niece and, I don't know, they's about sixteen in my house at one time. We never did, never did think nothing about going hungry or nothing like that now because I kept two good milk cows, and I killed two or three hogs ever year. We had a yard full of chickens. Only thing we had to buy was a little sugar and a little coffee and then I got to raise my own wheat and have my flour ground. And we lived like if I want to go walk to Tryon right now, get out here and walk to Tryon quick as you would go walk to your car because you had no other way of goin' unless you go in a wagon or a buggy one, yessir. I've left [Grover's] over yonder at 11 o'clock at night and walk home, right over here, yeah. I walked five miles over yonder on the road over here I bought a little old piece of land here and I walked five mile be over there at 4 o'clock in the mornin' build a fire. Get the mules out and go to work and go to the South Carolina line and I done that for a long time. I done all kind of hard work and work wont hurt you, I can tell you that, it would done killed me. Now my wife here now is my second wife and she working ever day at her job and we still livin'. I guess I'm the only black man ever lived in this country didn't have to go to Welfare for nothing, helping hand or nothing like that. I made my own way. My daddy died when I was two years old and my mother raised us. Ever picture you see, you know, she raised five of us. We… Mildred Proctor: It's gunna to get cold. WP: Well, I I'm just about I may eat a little cheese, I've just about done all I'm gonna do anyhow. I'm gonna eat some of this cheese here. [inaudible] Uh no, down there, my old man I was telling you about? It's about four miles down there to the church down there where he's buried at and it's on the tomb rock how old he was, what year he was born in, and what year he died in, and if you want that record I can ride with you down there and show it to you. I: Mr. Proctor, what do you know about your grandparents? Do you remember anything about your grandparents? Who were they? WP: Well, my grandmother was a Dickey and, uh, that's about the only thing Lou Dickey that was my grandmother's name, she was a Dickey and her name was Lou. I: Lou Dickey? WP: Lou Dickey. But now as for grandmothers, grandparents, I mean daddy's, I don't know 'em. Nothing about him, he died, but my daddy died when I was two years old I know that. I heard my mother talk about that many time but, when I think about my grandparents, all I know is what my [inaudible] well, she [inaudible] thirty some years, I guess. Yeah, was thirty some year. I: Your grandmother did? WP: Yeah uh-huh. I: Where was she from? WP: She was from Rutherford County on Bills Creek. I: She was born in Rutherford County? WP: In Rutherford County on Bills Creek. Now you want to talk about that and, uh, I: What did she do for a living? WP: Uh, well the only thing she ever done, one time we stayed and helped, we had to walk about four mile each way and she washed over here old fellow [inaudible] over there I: She washed clothes? WP: Uh-huh washed clothes for him and I'd draw the water when I was big enough to draw water for her and that's the only work that that she ever done, and my mother, she's worked in fields and stuff like that. I: What was your mother’s name? WP: Mamie. She was a Proctor and she married a Payne. She was married twice. My daddy was a Proctor and, uh, she married a Payne the second time and they separated after about three, four, or five year and, uh, I: Let's see, do you remember what year your mother was born? WP: No, I don't. No, I don't. I believe she was 85 when she died and she's been dead about twenty year now. Let's see, I got a record there somewhere. 1890… I: So she first, she married a Proctor first? WP: Right, right. My daddy was a Proctor. I: Okay, now, was your mother born in Rutherford County? WP: Yeah, I'm satisfied she was 'cause Bills Creek… When I knowed anything, we was livin' in Rutherford County and Bills Creek's in Rutherford County, Bills Creek is, and when I knowed anything we livin' in Polk County. No, we livin' in Rutherford County, right at the line, that's right. And we moved from there over into Polk County, that's right, and she must have been born in, uh well, Lou Dickey come from Rutherford County, I know that. I: And what about your dad, where did he come from? WP: My daddy? I don't know, he died when I was two years old and I know that. I: What did he die from? WP: Huh? I: What did he die from? WP: Uh I don't believe I ever heard. I know he was a young man. I don't know how old he was though. He run a blacksmith shop. I: And what was his name? WP: Charlie Proctor. I: Charlie Proctor? WP: Charlie Proctor. I: And he ran a blacksmith shop? WP: Yeah. Yeah, he run a blacksmith shop over there at the county line, right on the line. I remember hearing my grandmother talking about that. I don't didn't know much about, see she… this man was bought over at Mill Spring he in later years bought her sister. I: Now tell me about that. Who was that? That was, uh WP: Lewis's, I believe. I: And who did they buy? WP: They bought, uh Lou Miller, I mean Lou Dickey and, let me see now just a minute, Miller yeah, uh well, she had to be a Dickey too, Lucindy, Lucindy Dickey and Lou Dickey, they's sisters. Now what happened, uh, they had a big old rail fence around the house and the man owned both and when, the Yankee's would ride come in here and free the black folks why they, come in there with them horses and jumped over them rail fences round the house, about eight or ten of 'em, and went in the house and got that old man out and took him over and like to beat him to death and they run off and laid over in the cotton fields somewhere at night, rest of the night, and just huddle down together in the field over there. And, uh, they got through with that old man, they took him back near the smokehouse after they had done beat him to death nearly and took his, uh, all of I: Now, who was he? Was he the owner? WP: He was the owner. I don't know who he was now a bit more than you do. I don't know whether he was a Lewis or who he was but, anyway, they didn't kill him but they give him a good whipping. And now the sad part of the whole thing, uh, the man that own 'em, he was real good to 'em but when they come in there and say you got to get out of this house now, you got to go, you ain't got nowhere to go. She said they ate [broad leaves and salad] I heard her say that. They was about passed death. See what people didn't give 'em and he, uh them Yankees was so nasty they they place of whipping 'em and lettin' 'em go they took and all the meat and stuff they wanted, you know, maybe nothing handicapped there, you know, nothing to eat you know, hardly, and now his make his grandmother hear her talking about when they got down to where they had to eat [broad leaves and salad] they had to survive some way, they had to do the best they could and, you see, they had to get out of them houses. They wouldn't tum 'em loose and they come down there and force 'em out. When they come in there with them big old horses and jump over them rail fences they had, most all of them big folks had rail fences around the house, you know, and them big old horses pay a bit more attention than run up there and jump over them fences around that house and go in there and get that man out of there, they didn't bother nobody but the head of the house. They didn't bother his wife or kids or nothing else. I: What happened after that? WP: Uh, they had to get out and go, uh I: And is that how they came up in this part of the country? WP: Well my mother, I mean my grandmother and them was sold up here at Mill Spring. I don't whether she continued on living in Rutherford County or Polk County or where she continued at. I don't know that, but, they had to get out of that man's house but now where they went to, I don't know. But, see all the black people they white people where they owned was Moore's down there they owned they had forty some right down the road down here. They had Moore's down there had forty some of colored slaves. But now she said them people that come from Tennessee and Virginia come in here in them old covered wagons with a big pair of horses hooked to the wagon, and they had a cover over 'em and they'd buy a load of black folks and some of 'em from Tennessee and some Virginia and they leave out and they never know where they went to or who the people was and know a thing in the God blessed world. And see by that man buying her sister up at Mill Spring, that was a lot of help to her. She knowed where her sister was at, but, I don't know whether she had any more brothers or anything. I don't remember anything about it knowing nothing about it. Yeah, she had another sister named Ann. Her people lives over at Spindale. Ann Davis, that was her sister, she married a Davis. I don't know who she was. I guess she was a Dickey too, but that's all them old people's dead anyway, but I know two of the grandchildren over at Spindale but I wish the only thing that I could of kept a, well in fact, I had a house got burnt and, uh, I had a lot a records of everything that happened long time ago. People that got drowned and people got killed and, uh, all different things and I wouldn't a took nothing in the world for that and I could place a lot of things but that book I wouldn't a sold for no price because everything that happened I'd all us had a rule of it, I'd just come and put it down, you know, and days, you know, like that in it and I'd keep up with a lot of things and a lot of people want to know a lot of things and I could, uh, you know I had a record of it. But, as far as knowin' too much about my grandparents, very little I know about 'em and, uh, this old, uh, this old lady, what I tell you about my grandmother's sister, her husband is one is, uh, a hundred and eighteen years old now that I was tellin' you about. Yeah, that's right. Her husband, old man Sam we'd go down there and get him and, uh, bring him up to stay up at our house four and five weeks at a time and he'd sit there, we didn't have no stove had fireplace make your coffee and your bread. Now something you couldn't believe, you can take a pile of ashes right here now in a fireplace and take and rake 'em ashes back, you know, and make you up a pancake and take it and put it in them ashes and cover it up with ashes and then you can take it out and blow it a little bit and you better get all them ashes off, and that bread is just as sweet as it can be and you can eat it right like that. Don't even have to put it in a pan or nothing (chuckles). I: What did you call it? WP: Well, we called it at that time, uh, I: Ash cake? WP: Ash cake, right! Ash cake, yeah! Yeah that's what it was and it was sweet. It had a good taste to it. But now all houses long then, when used back in [inaudible] they'd never know to put it in the fireplace. They had to have something on the side and the back and stuff like that and then they used, a lot of 'em didn't have no stove, and they make their coffee on there and put the pan on there and fry eggs and stuff like that, you see. I: Right on the fireplace? WP: Yessir. Yessiree! Just rake the coals out of there and set the pan down on it and, oh, we cooked that for years. The first house I lived in over yonder, I can take you over there now and show you they ain't no [seal] in it. See, we built the fire on top of the stove and, uh, and cooked. Cooked, uh, well get up about 2 o'clock and start cooking us something to eat, you know. I had to walk five mile and, uh, they find smoke goin' all over everwhere, big, black smoke and they ain't no seal in it at all. I can take you over there and show you that house, right over here. I: What was life like for you when you started out? Just you and your dad and your mom. You and your mom. Did you have other brothers and sisters? WP: Yeah, I've got, uh, two more brothers and, uh, two sisters. I: What were their names? WP: My oldest brother named Floyd Proctor and, uh, the other brother was a Payne. He was Lawrence C. Payne and my oldest sister was a Proctor. Her name, but of course she's dead and, Lawrence C. was my half-brother, He's Lawrence C. Payne. I: Did you just have one sister? WP: I had two sisters Essie, Essie Payne, that was Lawrence C. Payne's sister. I: When did you start to school? WP: Well, uh, the first school I went to was the Zion Grove in Rutherford County, it was about four miles, I guess, to the school house in Rutherford County. I must have been around five or six years old, about six I imagine, five or something. The thing that's so much different then than it is now, is it was hard to keep within. The next school I went to walked a way over yonder to right up here. See, we only had school four months and my mother had nobody to help her. We had to gather corn and pick cotton and anything we could do to help make a livin', you see. And so actually, I guess actually altogether, I wouldn't be able to go in school two months out of a year. Well, they had four months of school and we had the… Well, my mother she worked around here and yonder for like I say she worked about 10 or 12 hours for about 25 cents a day and the least I reckon I worked for was a dollar because that was about 12 hours a day. We didn't have no it was sun-to-sun, a dollar a day. And when Rutherford County had a hospital open up over there they was five black women went over there from here and they get 12 dollars a week and that was big money then and they had to work six days a week for 12 dollars and then they had to pay their ride backward and forward which gas was about 12 or 13 cents a gallon and somebody had an old car and they took all of 'em back and forwards to work, you know. And they had to pay their ride bill out of that and they eat out of that and that where they gettin' 12 dollars and that was good money then. That'll make you a many a hard days 12 hours for one dollar. I: How old were you when you started working full time? WP: Well, let's see. First thing come here from [New York] and bought that place over yonder and that's the first job as such. I pulled fodder and corn and stuff like that but, you know, but that wasn't no full job you see that was just something you had something this week to do and next week somewhat else but, now, I worked for a lady setting out trees over here, uh, I must have been about I guess seventeen or eighteen years old when I first went to work for her. I: During that period of time, do you remember anything that had an impact on your life, like a flood or-- WP: Yeah, the 1916 flood. That was year my brother was born in. Everything got washed away. All up and down the road, lord a mercy, I went down here and looked at it and they's an old barn and an old thing that was goin' down the river. 1916, I mean that was a rough time in this country. I: How old were you about that time? WP: Well, let's see…. let me see now I don't remember that I don't know what year that was he was born in 1916 and I don't know what his birthday, must have been July, I believe it was July. I know me and my brother had what you called a four inch club. We had a corn, two acres [four each] going in, but we had two acres. I had a acre and he had a acre and we had to brought in some good sheep manure and cow manure and tore it out of the sacks and spread it in there as a fertilizer. We had no fertilizer then, you know, and let's see, I don't know I don't know exactly how old I was to save my life. I: Just come close. WP: I must have been about fifteen or sixteen years old. I: About fifteen or sixteen? WP: Yeah, something like that. I: What was the flood like? I mean, did it destroy people's stuff? WP: Everything, on the river. Bridges, fields, corn, everything. I: Did it get your corn? WP: No, we had, uh, four each. We had two acres. Me and my brother had two acres that was up land, they wasn't no bottom land and we made enough corn see to do us, which a lot of people had them big bottom land and lost everything they had, watermelon and everything, corn and cane patches and everything, mules and hogs and everything got washed away. I: So it took animals? WP: Yeah, oh yeah. A lot of animals got destroyed. Lord, yes, in them barns they couldn't get 'em out and they in the pasture they couldn't get 'em out the water rose up over the water got about eighteen, nineteen foot deep in some places. I: Well, how did you all live? Did... you all weren't in the flood? WP: No. No, no, we weren't in it. My brother was born at that time, in that year, but we were about a mile and a half or two miles from the river. We didn't have nothing on the river at all ourself and the government, they give a lot of people this millet they called it, and sent feed in here from different places to help people save the some of 'em had livestock and nothing for 'em to eat, you know, kind of like they did here you know back when the drought come, but, uh, now you couldn't you could get on a train here in Tryon and go to Cincinnati, Ohio, anywhere you when you got to Cincinnati, Ohio, why you could get up back here and go up and sit down anywhere you wanted to on the car in the train but you didn't get nowhere but in the back till you get to the Mason Dixon Line and you cross that Ohio River and sit down on the street car. I went there in 1925 and stayed five months, in 1925, and, (chuckles) you could tell the people from Georgia and Alabama and Florida and down in here you could tell 'em just as good when they get on the street car up there or something or another to ride, and see 'em settin' over the side the corner all drawed up. When them old guys raised up there, had been mechanic, he sit down by one of them white gals left, she move over and might not. These men down here, he stand up 'fore he'd set down beside of 'em now (laughs) cause he wasn't used to (laughs) he wasn't used to that stuff (laughs). Thought somebody would kill him, you know, lord a mercy. I: How were things between races when you were growing up? How did they get along? WP: Well, uh, uh, I tell you about myself. I always got along myself with the white people, in fact, I worked in a store over here five years right after I got married. And I met… all our business was chickens and eggs and feed and beans and com and cotton and different things and nobody had any money much but they had eggs and chickens and stuff like that. But, uh, I got along real good. I had one little thing happen to me. They's one boy lived across the river over there, he died, ain't been too long ago, white boy, and he would meet me coming from the store or somewhere around and he would walk up and shake me, you know, and mess with me, you know, like that you know. I told momma one day, I said "Momma that boy, that Howard boy over yonder, he just, every time I see him he mess with me and I'm gonna knock the soup out of him." He says his momma says: "Boy, what you talkin' about, don't you talk about hitting that white boy they'll kill you boy they'll kill you, I tell you, don't you think about hitting that white boy" and went on so. I believe it was on Saturday, I met him way out there on the curb, he come up and grabbed me. I laid it on him and I mean I gave him a good one (laughs) nobody pulled me off of him but I was scared though and I really give him a whipping but momma she never did know she never did know in her life she never did know that I hit that boy. Why she'd have got on me in a minute for whipping, hitting that white boy (laughs). But, I'll tell you the truth, they's so much different in time now. I was in Charlotte the first time I went in a cafe to sit down where I could sit down and, uh, eat a meal in a cafe, a white cafe, had to go to little old windows and I had my boys sit in up here at town I had two boys and a niece and some of my grandsons come in from Buffalo, New York, and he had a little old girl about four years old and he bought her some ice cream or something, and he walked out on the street and left her sittin' on the stool, right up here in town, and he come back and his girl was gone. He didn't know what what - this is a quote: "Where's my daughter at?" Someone says: "She's over there behind the door in there and I couldn't serve no black in there." He come on down here and got with my son, the two of 'em, niece, and two or three more and they all went on back up there, son-in-law, they all went back up there and set down in the place and ordered something. They wouldn't serve 'em and they called the cops, you know. My boy knowed the old cop and when he come in he called "Hey, Ken, how you doin" (laughs) made 'em look at 'em. Wasn't too many years after that till they had to open the door, but, it was a time. I want you to know, it was a time. But now what I was gonna tell you now, this man that sheriff up here now in Polk County sheriff Carwell, they's, uh, five of us one night ridin' around in a car, I was the only black in there, went to a drive-in over here in Rutherford and, uh, they ain't suppose no black go in there. So they start to tum off to go in there and I told 'em "Uh-huh boys, I can't go in there" and they says "Oh, yeah, you can too said you can go in there if we go" and they went on the ticket agent looked and looked and never said nothing, go on in anyhow. Well, the same night we went out next to Shelby to a big fish camp down there and no blacks allowed in there either. He got out and "Come on, Will" and I said "No, I ain't goin' in there, man. You get me hurt. I ain't goin' in that place." "Oh, yeah, you goin' in there if we, if we eat share what's up here right now." He says: "If we eat you gonna eat or we don't nobody eat." Went on in there and they treated me just a nice as they did anybody, nobody never said a word, and over here at that store that was one that little old white guy he's the only one I reckon I had any...... well, I had a gun snapped on me one time over there. What happened, one Sunday I was going to see my first wife, before I married her, one Sunday evening, she lived about half a mile. It was on Sunday and I was in my shirt sleeves, and I carried a pistol for ten years. A little lemon squeeze pistol. I carried it for ten years, when I put my pants on I put my gun in my pocket, that's how often I carried it. Well, on this particular Sunday, Sunday evenin', I was walking right up to see my wife, another boy walking along there with me, we went by a little old store right there and they's three white guys, they's throwing rocks in the store, tearing up the showcases, glasses out of the store .... I: Whose store was it? WP: It was, uh, this man run the store up here, John Edwards, his daddy and his boy run the store up here and his daddy's store at that time. I: Well, why were they tearing up the store? WP: They's mad at the daddy about something, I don't know what it was but, anyhow, they's three of 'em and, uh, I just walked on, me and this boy walked on, and got right even one of 'em threw at rock at me and I dodged the rock. And so another one come out with a big old gun about that long, snapped it on me. Now I'm walking off sideways, feeling my gun, every time I moved I feel my gun. I carried it ten years. Every time I moved I feel my gun in there. This other boy run, run on down behind the house down there. I didn't run. I just walked on off. I felt my gun and decided I didn't have it and just walked on off. Well, uh, this lady in the house, that white lady, he throwed a rock up there and hit her on the breast and knocked her backwards in the floor and she saw what was going on. Well that night the law come down to my house and talked to me about it and my mother about it and asked what happened and I said "Now I don't want nothing to do with it,” in fact, I says “the man that snapped the gun on me I don't know who he was a bit more than nothing.” I don't know who he was or nothing, and I says I don't want nothing to do with it. I live here and I don't want nothing to do with it." He says "Well, one thing about it, Miss Edwards uh, she done give us the name and say you gonna have to attend court." I said "Well, I'd rather not have." He says "Well, I can't help what you'd rather not have nothing to do with it." Well, I don't know what, boys when I got to court I just told the jury just exactly what happened. They said "Well, what happened?" I said "Well, just started walking along the road there bothering nobody and I said I know they wasn't mad at me about nothing 'cause I hadn't never, some of 'em I hadn't never seen, they's one of 'em that snapped the gun on me, I never had saw him before in my life. I says he didn't have no right to be mad at me 'cause I hadn't done nothing to 'em and hadn't had a hard word with 'em or nothing." That old jury said "Well, a man walking along the road tending to his own business and not bothering nobody, and a man pulled out a gun and try to kill him." And he done emptied the gun in that house or probably I'd a been dead and so, uh, the jury said "Well, I'll give him eleven to thirteen year hard labor." All right then, the boy that throwed the rock now he got from nine to eleven year. Well they's one boy along eighteen years old, he didn't do nothing but he was along and they give him three years and a half in the chain gang. Now that's what they done with 'em, right up here at Columbus. I didn't want to swear again the man. I didn't know the man and he couldn't be mad at me about nothing and that's what I told the judge I says "I didn't want if you turn him loose it will be all right with me because he's just one of them old drunk fools" is what I called it but that judge didn't look at it that way. I: About how old were you then? WP: Well, let's see, I was about twenty years old, nineteen, I was nineteen years old. I: Were you working full time for somebody then, when you were twenty years old? WP: No, I work at the saw mill for [Shay Horton, backwards and forwards, Shay] Horton. Worked a few days for him and, uh, that lady that set out trees about three or four days a week there and this white lady took me to Tryon to the hospital and had my tonsils taken out and they had to keep me all night and she paid thirty-five dollars to get my tonsils taken out. It'd be five hundred dollars today, I guarantee you if you pay it now, it'd be five hundred dollars to get your tonsils taken out. I: Well, did black people and white people go to the same hospital? WP: We go to the same hospital but we didn't go to the same room. You had, uh, the black had in Rutherford hospital they had a place way off down here for 'em but in Tryon they had 'em in the basement. No, they didn't have 'em together, they didn't have 'em together at all. I: Did you go to school with whites? WP: No, no, no. First time I knowed whites could go to school was 1925. No, it was way on later, way on later. Old fellow down at Thompson, he's a school teacher up here at Tryon, and Charlie Carson come down there one Sunday to see me and tryin' to take up money to try to get a lawyer, get it where the black could go to school here. And I give 'em fifteen dollars out there on it and, uh, they got a lawyer out of Asheville, fellow Gudger, he's a judge now, he knowed me ever since then. And they just opened the door after they found out the fellow they opened the door. If we hadn't a put no pressure on 'em, we wouldn't a went, that's what would a happened. I tell you if it hadn't been for Martin Luther King, they's a lot of things done happen in this world if it hadn't a been for somebody like that stepped out there. Sit out there on the porch one night down in Atlanta and the old colored lady there knowed Martin Luther King and know where he's buried at, knowed all the history and everything. She sat there about, oh, I sat there about two hours and half or three hours one night talking to her because we was blocked in and couldn't leave no way, and it was awful how the man was done down there and the way people treated 'em down there. And you know, of course I guess you do know too, you know a lot of the black people that didn't go along with Martin Luther King and him tryin' to do everything he could in all his power even to help all the black race and they's some of 'em said "Aw, he's just gone too far with it, gone too far with it." Just like down here, this man in Spartanburg, can't call nobody's name half the time, what's his, uh, Roan, Red Roan, you read about him or hear of him I know, well I know him well, you know, he used to be a pastor at Tryon and, they's a lot of people he talked people that's supposed to be intelligent people and they said "Well, he's going too far with it" and what he's trying to do is get our equal rights, what you supposed to have whatever you can handle let you have it. Don't be because of the color of your skin. You don't have to pick certain things you can do 'cause you're black. Lady called me the other night, eleven o'clock, and, I got a home up here, different [shade] up here in Polk County, and I'm the man that got 'em on there. I's the man put [‘em all on] on there, first black [baby] they ever had in Polk County, I put 'em on there. I'm the man that done it and something come up that's necessary, I'll walk right out there, I don't care who it is and set up for rights and then they know that I will. I don't get along with them judges, some of them judges. One time they's a judge up there, they's a colored police and his wife lived in the same house another little old girl lived in, one lived downstairs and the other one lived upstairs. Well, they got into it about the kids, you know, and, uh, well, the police wife she told her side of it and this other girl told her side of it. Of course, her being a police wife the jury took side with her, you know, and I just very plainly walked up and told 'em, I said "Now, I'm gonna tell you something," I said, "I been going to court now six years, I don't like what you're doing. It ain't right, I don't care 'cause she's the police's wife, she can tell a lie good as the woman ain't never seen the judge as far as that's concerned." I says, "I can’t deal with this" and they give her six months in jail and I said "No, we ain't gonna do that." I took appeal on it right then. I told her to, she went on and took appeal on it, and then when the big court come up, district court, I mean superior court come up, why they turned her loose. But they were taking advantage of her, you know, and I let 'em know that I didn't like it at all. Wasn't no use me bitin' my tongue 'cause I didn't like it and she's a little old girl and she'd had a kid and wasn't married or nothing but she's still a human being. MP: Jessie Court want to talk to you about Parker, that man they sentenced to 40 years. WP: Oh yeah. Well I’m ready to talk to him anytime. I’d do anything for that man. MP: They said they would drop the charges if you can get Leonard to do it. WP: Well I’ll sit down and talk to him. If I can’t talk to him nobody else can. MP: Lord I know it. How come they count on you so much. WP: Well when the time comes, try to get him in office and then if something ain’t right they know I’m going to try to stand for right. Well, uh, I just settin' here talking. I don't know whether I'm doing the man a bit of good in the world. I just going over a lot of little old things you know that, uh, a lot of little old things that, as I went through life that he'll never be able to go through with, never will, no way. I: What was church like? Is there a difference in the church now? WP: Well, uh, I tell you back yonder then that, uh MP: it sure was a lot of different as far as religion and love. WP: That's right. See what happened, see she's a, she's a minister too, you know. MP: Oh, yes. Way back then when you's commin' along so I can answer that, way back then folks loved each other, but now. WP: I tell you what happened, uh, the Baptist's they had a preacher and he wouldn't more and get started preaching good till he'd be running the Methodist down. Go to another church and he's a Methodist and he's running the Baptist down, you know, making it altogether different. But, today it don't seem to be that kind of a thing. Well I can tell you a little incident that happened down here and I don't like it, and the man's a good speaker too, but, they got one church fell out with the preacher or something and they go about halfway from here to this road up yonder and build another church and name it the same identical name and I don't go along with that. My son, he thinks it's all right and well, the other people all in all formed up but one or two men, two members and I says I don't care if they wasn't but one person in that church belonged to that church right there, they had no business to go right down that door down there and build that church when they had places all over the United States to build churches except that one place go right down there, in hollering distance now, and then when they got ready to bury someone the man could preach a funeral down there but he couldn't come up here and put him in the ground up here. Wasn't allowed up there. Now see I mean, I don't care what it is, it's just right and wrong, it ain't two ways now. You either gonna be right or you gonna be wrong and now that's for sure and I'll say this and I'll still say it, I'll argue I says the man wrong a going right in the, maybe two or three members, I say one, they two or three in this old church in here and they had to overhaul and this old church is in debt. I got a daughter buried there and a son-in-law buried there at this old church and I got a grandkid or two buried there, but, I didn't look at it that way. I looked at it this way, it wasn't right to take the privilege away from these two old people been there all these years now, and go right down there and pull all the church members down there with them and leave them settin' up here on account of what it was. This church down here was a Whitehall Independent Church and this one up here was a Whitehall Methodist Church, or Baptist church or whatever it was, don't make no difference. And the Independent down there Side Two: don't think about nobody but yourself, you in bad shape, now you in bad shape and I'll argue this as long as I live, I don't care who it is, if you're wrong and you admit you're wrong, there's hope for you, but, if you know you're wrong and you claim you're right, they ain't no hope for you 'cause you, you, you ain't got no way of gettin' forgiveness or nothing. You know you're wrong and you want the Lord, you tryin' to fool him or what you tryin' to do. People, I don't know. I call it ignorant my self. I throwed a lot of rocks in my life but now they's one thing about it, I kept my hand in front of me. I don't believe in that, none of this here Bakker stuff they got going down yonder. I don't know whether it's all so or whether it's all a lie or not but anytime you got money, that much money involved, you've got some crooks somewhere. I don't care what it is. What kind of concern it is, you've got some crooks somewhere when you've got that kind of money involved. I ain't got a bit of education, but, I do know one thing, I believe what I believe and I know I've worked all my life and, and, uh, you can't make but so much money workin'. If you don't have some kind of business or something another else beside workin', you can live, make a decent livin' but that's about all. You ain't gonna accumulate a whole lots of something unless you got something else workin' for you. Now what I done, I done a lot of things that a lot of people didn't never think about doin'. I hauled herbs to Asheville a long time ago. Buy 'em here and make a cent on the pound and haul 'em to Asheville and when my little old boy got big enough to work I went into the building business. I: What kind of herbs did you haul to Asheville? WP: Oh, uh, apricot vines, cherry bark, haw bark and, ginseng, and star root and just all kind of herbs. I: Where did you get the tuff? Where did you get it to haul it? WP: Well, they's people around here that didn't have no jobs or nothing to do. I had one old crippled fella up here that didn't have one leg, he'd get least three or four hundred pounds of apricots every week, vines you know, and dry 'em for me. And he made a little money out of it for living. All right now, my boys got big enough to work they picked a few apples, a few peaches, a few cucumbers or something like that, nothing else. Well, I had a good meat business. I furnished five markets every bit of the meat they had. Tryon, Rutherford, Columbus, they's five markets I furnished 'em all meat. Hogs and beef, calves and everything, but one day I was studyin' about something. Now I got boys here big enough to go doin' something besides pickin' cucumber and apple and stuff like that. Well, I hadn't never made my mind what to try to tart doin' something. Talk about their minds, now an old fella come down here had a daughter lived way out yonder somewhere wanted a house built. I told this old man no, ain't no way I could build a house, lord no. He says "Oh, Will, you can build a house. I’ve been trying I can't get nobody." You know I let that old man talk me into it and the old house settin' up on the road right yonder now, the one I built. I went on and built it and the lady come in and she liked it fine. The roofs steep. I couldn't do nothing about it cause that old man wouldn't let me put it down like it ought to be and you know what I done? I commenced on that old house there. I [inaudible] to build a big old building down there, a block building. I couldn't read a rule. I couldn't cut a rafter. I didn't have a hand saw. I had an old bow saw and (chuckles) I went on and I went in business and I stayed in business thirty-two years. I built a nursing home. I built several big churches. I built about a hundred houses through Tryon. Savings and Loan over here in Tryon and (Chuckles) and our super market you see in Columbus over there on the right hand side as you go in there, I built that building. I built, I built a nursing home in Forest City and then went on and built another one. I stayed in business, I say after I first started, I stayed out of work about, I'll say four weeks from the time I started and most all my work was white, the most of it was white. I had some, you know colored, but what I mean, the white would come around that liked my work and they's one thing about it, I didn't allowed no drinkin' on my job and if I smelled whiskey on you today, you wouldn't be back tomorrow 'cause I didn't have it. I tried to run strictly business you know. And so my daughter in Buffalo, New York, she's talking to a white lady, one lived here and another one lived here, and, uh, told her says "Why don't you try to get your father and mother out of the south, it's awful the way they treat them people down there." She says "I don't know what you talkin' about, says my daddy's been in business down there for the last twelve or fifteen years and says he gets along as good as anybody looked like could get along down there and says I never have heard tell of them having no trouble out of 'em. She says "Well, it ain't what I've been told." She says, "Well, you've been told something wrong" say "if you act like somebody you can get along with them people down there." But, they's just so many things that we bring on our self and then we blame somebody else for it. I had eight girls here and if some of them a few lived around here if I see 'em coming down the road up yonder and I thought they's drinkin', I didn't stop 'em down here in the yard and say "Hey boy, where you goin'?" Uh-huh. You goin' the wrong road, you want to go up that way or down that way, you don't want to come down this a way, I know that. A lot of people like that, you know, I wasn't biggety, it wasn't that, I just had to have rules to go by and had to my family had to be respected, and I couldn't let a bunch of drunks come in here and slobber around here. I couldn't put up with it. So, I guess I got along about as good as the other fella can. I can sit here and tell you a million things and it wouldn't do you a bit of good in the world but now if they's any special thing you want me to do or want me to say, I'll try to get it over with. My wife's gonna whip me about this cheese, directly. (laughs) I: Do you recall any holidays, growing up, that black folk celebrated that other people didn't celebrate, any special day? WP: No. No. Now, uh, Miss [Colerman] told me the other day, wanted to know if I knowed anybody else. Now, I've got a friend up here at Mill Spring, me and him lived together in 1925, and went to Cincinnati, Ohio. He had been up there before that and worked two or three different time but they' five of us young boys got together, around twenty or twenty-one year old, and went up there in 1925 and, they's a lot of colored people have you had anybody contact you about Della Jackson? Well, she's a school teacher and she's about my same age. They mentioned her. I: Yessir. I was trying to find her today. WP: Yeah, well, [inaudible] Mill don't live too far from her and he's another one that they's two people right there that can help you a whole lots on almost anything. Miss Della Jackson's mind is clear.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Willie Proctor is interviewed by Edward Clark Smith on April 2, 1986 as a part of the Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project. He was born in Rutherford County in 1904 and moved to Polk county when he was still young. He recalls his grandmother’s stories about being sold into slavery and details the time she was freed. He raised a large family and talks about working, how he got into the building business, getting by on very little, and church. He recalls the 1916 flood. Proctor shares his experiences before and after the civil rights movement.

-