Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (19)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- 1700s (1)

- 1860s (1)

- 1890s (1)

- 1900s (2)

- 1920s (2)

- 1930s (5)

- 1940s (12)

- 1950s (19)

- 1960s (35)

- 1970s (31)

- 1980s (16)

- 1990s (10)

- 2000s (20)

- 2010s (24)

- 2020s (4)

- 1600s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 1910s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (15)

- Asheville (N.C.) (11)

- Avery County (N.C.) (1)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (55)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (17)

- Clay County (N.C.) (2)

- Graham County (N.C.) (15)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (40)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (5)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (131)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (1)

- Macon County (N.C.) (17)

- Madison County (N.C.) (4)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (1)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (5)

- Polk County (N.C.) (3)

- Qualla Boundary (6)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (1)

- Swain County (N.C.) (30)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (1)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (3)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Interviews (314)

- Manuscripts (documents) (3)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (4)

- Sound Recordings (308)

- Transcripts (216)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newsletters (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Publications (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- African Americans (97)

- Artisans (5)

- Cherokee pottery (1)

- Cherokee women (1)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (4)

- Education (3)

- Floods (13)

- Folk music (3)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Hunting (1)

- Mines and mineral resources (2)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (2)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (2)

- Storytelling (3)

- World War, 1939-1945 (3)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Sound (308)

- StillImage (4)

- Text (219)

- MovingImage (0)

Interview with Zenophon Cook

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

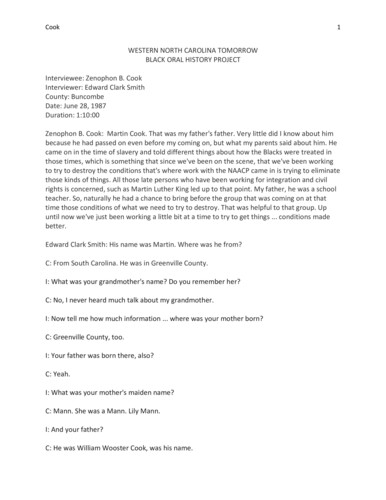

Cook 1 WESTERN NORTH CAROLINA TOMORROW BLACK ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Interviewee: Zenophon B. Cook Interviewer: Edward Clark Smith County: Buncombe Date: June 28, 1987 Duration: 1:10:00 Zenophon B. Cook: Martin Cook. That was my father's father. Very little did I know about him because he had passed on even before my coming on, but what my parents said about him. He came on in the time of slavery and told different things about how the Blacks were treated in those times, which is something that since we've been on the scene, that we've been working to try to destroy the conditions that's where work with the NAACP came in is trying to eliminate those kinds of things. All those late persons who have been working for integration and civil rights is concerned, such as Martin Luther King led up to that point. My father, he was a school teacher. So, naturally he had a chance to bring before the group that was coming on at that time those conditions of what we need to try to destroy. That was helpful to that group. Up until now we've just been working a little bit at a time to try to get things ... conditions made better. Edward Clark Smith: His name was Martin. Where was he from? C: From South Carolina. He was in Greenville County. I: What was your grandmother's name? Do you remember her? C: No, I never heard much talk about my grandmother. I: Now tell me how much information ... where was your mother born? C: Greenville County, too. I: Your father was born there, also? C: Yeah. I: What was your mother's maiden name? C: Mann. She was a Mann. Lily Mann. I: And your father? C: He was William Wooster Cook, was his name. Cook 2 I: How did they earn a living? C: Farming. I: Did they own their land or did they sharecrop? C: Yeah. My father owned his home. I think my grandfather rented his land. I know he did. But my father, it went out from him. There were nine brothers. They all went out to get their own homes. There was only one in the family that, he never was interested in owning a home. I: Now both your mother and father were from Greenville County. Do you know how they met? Have you ever heard any stories about how they met each other? Did they meet in Greenville County? C: Oh yeah, it was in Greenville County. I: They married there. c: Oh yeah, they married. I: That's where you were born? C: Yeah. I: How many children were born to your mother and father? C: Two. My sister and myself. I: And what was your sister's name? C: My sister's name was Tarquenous. My name is Zenophon. I: That sounds Greek. C: That is Greek. I: When did they first move to Asheville or to Buncombe County? C: See my father never was in no county. He lived in the past in South Carolina. I left home when I was in my teens and came here to Asheville. Went to work in Battery Park Hotel. I: Was that why you came, was to get work? Cook 3 C: Well yeah. I just grew up and wanted to get away from home. I wanted to get out and get gone. Decided to come here and go to work. I left home and had to go to work, so I came here to the hotel. I: How old were you? C: I was 16 when I came here to Asheville. Went to work at Old Battery Park Hotel. I: Going back, did you go to school? C: Oh yeah. I went to school in Landrum in the country and then when I left Landrum I went to Allen University in Columbia. When I left for school, the season was out and in the spring of the year I came back home. I: What was South Carolina like as you recall growing up? Did you have good schools that you recall going to? How long did you go to school? C: Oh yeah. The school terms then were times when you weren't needed on the farm. When the farmer needed you, you quit school and went to get your crops ready. I: Then how many months out of the year did you go? C: You usually have to come out in the middle of May, not later, and boys that were large enough to help on the farm had to be on the farm. I: So, did you go about three months? C: That's it. I: Of your brothers and sisters, how many children were connected to your mother and father? Did your grandmother and grandfather have other children? C: Let's see, how many were there? Well, as I said there were 9 boys and I think it was 3 girls. I: So, there were 13? C: There must have been 15. No, there were 12. I: What was Asheville like when you first came to Asheville? C: Well, it was awfully hilly, a whole lot different from what it is now. It was awful hilly and the streets mostly were stone, granite-laid, streetcars, the traffic was run with streetcars, trolley cars over here, and the streets were very narrow, of course. Some of them are still narrow now, but much narrower then. Lots of changes have been made, and as I say, it was awful hilly and, Cook 4 of course, a lot of Jim Crow (laws) and white water and black water. You'd see those signs of where you were supposed to drink and where you weren't supposed to drink. Of course, it was just about lots of places you couldn't go at all unless you was a servant. You wasn't allowed. I tell you, you wasn't allowed to go in. I: What was your first job at the hotel? C: Bellman. I: What year was that? C: It was 1918. I: What was the pay like? C: Pay? I: What was a good tip? C: You'd get ... that was the main thing in it was you'd get tips. A bellman then you'd get, maybe hand you 50 cents. That was a pretty good tip, 50 cents. But all under that was ten, fifteen, sometimes it wouldn't be but a dime; but 50 cents was a pretty good tip in those times. I: What was entailed? What did you do? You didn't have elevators and stuff. C: Yeah, that's what I did. I run the elevator and, of course, you had to carry these folks up on the elevator and their baggage and put them out to a different room where they would go to and they would give you a tip like I say whatever it is, 50 cents, or a quarter or 15 cents. That was it. Then at midnight, at least 11:00, all those that wanted to that was going to be on duty until the next morning all went into the dining room and gave them something to eat. Those folks that were on duty. Of course, that meant the White folks. I: You all couldn't eat? C: Huh? I: Black people couldn't eat? C: No, not in there. The only Blacks that ever got to eat anything were those who worked in the dining room and the kitchen. I: So, what as your weekly salary? C: You would get about $15.00 or $16.00. Cook 5 I: And that was a good salary. Now, going back to talk about school. You said Allen University. C: Uh-huh. I: Do you remember about what year you were going? C: Yeah, I went to Allen in 1916, '17, '18. I went there in the 8th grade and I left there, went there three times. I: What did you study? C: I went there in the 8th grade and after the third term was over, I decided this in the classroom. We had a chance to go after school was out and in the city, we could get a job for a few hours so long as you're back at the campus before dark. So, I taken up with the man who at one time was the governor of the State of South Carolina, Coleman Blease. I had taken a job up at his house, private home cleaning up and then finish and go back to camp, and they had learned to like me and I had learned to like them, so then as I decided this at the end of school. The professor was talking with us and I found out about salaries and I found out what they were getting. So having read and studied some about what could be made with other jobs outside, I found out that I could make much more money without me trying to teach. That was in 1918. See, I run right with the years. In 1917 I was 17, in 1918 I was 18. I'm 87 now and this is 1987. In '88 I'll be 88. So, I found out I can make more on the outside than staying in there going to school and becoming a teacher. That's when I decided to go to Cincinnati and go to Ray's automobile school, which I did, I came back home, stayed awhile, and left home and came over here. I: So you went to Cincinnati to Ray’s Auto school. What were you going there to learn? C: Automotive mechanical work. At that time, Ray's had the best automobile school there was in the country. I left Allen and then came home and stayed a while, and then I came over to Asheville and I stayed here until about the last of March, and I left here and went on to Cincinnati and went to Ray's Auto school. I found out when my principal in school was talking that I could make much more money than what he was making. I told him, "I don't think I want to stay in going to school if that's all I'm going to make, that you're making," so that's the reason why I left down there. I: What were they making? C: I forget what he said they was making, but it wasn't interesting. The price he quoted to me as him teaching in Chicago, I wouldn't want to put in all these years to finish up to not make any more money than that. The first job that I got after I went to Ray's School, I was making more in two weeks than the professor was making in a whole month. I went out and my first job was over $40 a week, back in them times because my qualifications for mechanical work with the Cook 6 cars. So I told my principal in school, "I'm not going to stay if I have to finish my way all the way through school to make what you're making." He said, "Well, somebody's got to do it." I won't disagree with that, but it would be someone that wanted to do that. I: So, Ray's found your job. C: That's the reason why I went there. I said I'm not objectionable to someone doing that and has to do. That is fine, but let someone do that that wants to do that. I: How long did you drive? C: 33 years. I: So, Ray's taught you to be a mechanic and a chauffeur had to be a mechanic, too. C: That’s right. I: That's how you got hired. C: To get a good salary, you had to be able to meet certain qualifications with mechanical work with your car. They would put you on a certain salary. I: So, you did a lot of traveling? C: Oh yeah. I did so much of that I got tired of it with them, but since I made all them dimes. I: That was in the '20s, right? C: That was from the '20s up until the '30s. Since then, I've done a lot of traveling myself. I: What's the difference in traveling that you've done since then? C: I've been to California twice on my own traveling. I've been to Portland, Oregon, on my own traveling. I've been to St. Paul, Minnesota, on my own traveling. I've been to New Orleans six or seven times, I guess, on my own traveling. And I'm not through yet. I: But I'm talking about when you were traveling and driving for people, you know you had to take the car, and they went on the train or something. How did the driver fare on the road like that? C: Well, you see there were places where you fared pretty well because you would ordinarily be dressed in your uniform and that uniform in the eyes of the Whites which you had to come in contact with, they would know good and well you weren't on your own. You wouldn't be driving that big Cadillac car, limousine, and they would know the money man had to be behind Cook 7 you. That put you through lots of places where you wouldn't have gotten through because there were some would give you the nose snub because they wouldn't like it no how. You didn't have it easy at all times, but, of course, you could get through as long as you had that equipment and get along all right. I: Did you ever have any bad times? C: No, I didn't have no real bad times. The worst time I had as right here in Asheville once. My boss man was in the store, and that's why I was stopped there, and he was in the store and I knew that’s where he was gunna be, and I was supposed to pick him up there. And, of course, the madam was in the back of the car and the lady that was going to give me the trouble, she hadn't noticed that. But anyway, I was pulled in, fixing to back in to park, and she was wanting to park too. And she saw me, and to keep me from getting the parking space, she run the nose of her car in that way and jumped out of it. That just meant that I couldn't back in and hit the car because there wasn't nobody in it, the car was standing still. So when she did that I hit the ground. I saw an officer coming up the street, I saw what she was going to do. There was an officer standing up the street. She saw him as she passed down. She was going to tell the officer to go over and get the boy, so I hit the ground. I said to the officer, "You see the positions of the cars? Do you see what she's trying to keep me from doing?" I said, "No, she wants you to make me move my car because I'm Black." I said, "I'm not going to move it. " By that time my boss man was coming out of the store. He said, "What's going on here? I said, "This officer here wants to make me move my car to let this woman get in here and I don't intend to do it." And my boss man said, "What's he asking? What's going on?" He said, "I think this is a smart talking Negro. He don't know." He said, "He's my driver. He stopped here for me." I said, "If you lay that Billy down I'll whup you or you'll whup me." I said, "That will take care of that." The boy grabbed me by the arms said you know you come on. He stopped me from [inaudible]. That was over here in Asheville. That was the toughest battle I had. But I didn't care. I was a mean little sucker then, but I didn't care. I said, "If you lay that Billy down, I'll whup you or you'll whup me right here on the street." No, I had on my uniform and everything, but I didn't care nothing about it then, because that's what he meant to do. Then three days after that I was back in town almost in the same place, couldn't get a parking place. This ole cop come over, I said, "Don't come grinning at me." Well you know he was in the wrong, and after he found out who I was, you see, he wanted to make up. I said no, don't come grinning at me. I: So you did that for 30 years. C: 33. I: Did you enjoy that? C: I enjoyed it because I was young. I didn't mind. Except I got tired of it. Then I had another one not quite that bad on Fifth Street. I was trying to get another parking space. This guy he wanted to make me move after I got my car in there. Wanted to know if I was going to move it. Go move it for what? I said, "Get out of your car." So I hit the ground. He drove on off. I was about Cook 8 to get in another one once, and the wife was in the car and she said she was glad when I stopped because she saw what it was leading up to. I was a mean buddy, I didn't mind it, see. [inaudible]. I: Had to show you. C: Yeah, you had to show me something. I was a man, and I knew it. I was a good man and knew that, so I was from [inaudible]. I: You were a bellman in a hotel. Now that was before you decided to go to the automobile school. I: What brought you off the road? C: Well, I got tired of it. I got tired of being away from home a lot, and I quit and went to doing janitorial work. I just got tired of it, but since I got to doing on my own, I love it now. I can't get enough of it. I: Now, when did you first get married? C: In February, 1923. My first wedding day. I: Who did you marry? C: A girl by the name of Anna Bruce. I: What were weddings like? C: Well, this was done in Cincinnati. I went to work there and had connected with a male course at the First Baptist Church there on the corner of Lincoln and Arm's Place. So, I had been there, I went to school, and I got a pin. A gold medal pin for attendance on time for the first year. Then the second year, if you do it, a wreath goes around that pin. Ingot that pin. I still wear it. I treasure it. And so I had made a big hit there you see, and a church wedding then wouldn't have to be lots of times you have all those candles and all those flowers. Back then you didn't have to do all that. Back then you had a big wedding when you had the minister and the family group and other groups from the church you wanted there. If you had them there, you had a big wedding. That was a church wedding. And then, too, the girl that I was getting married to, she won the first prize out of a contest of 25 women, a beauty contest. I: So, she was a pretty lady. C: Yeah. I: And you all lived in Cincinnati. Cook 9 C: Yeah, lived in Cincinnati. Then I came here, brought her here in '25, in June, and at that time I went to work at a creamery house, Southern Dairy. It was on the corner of Clingman Avenue and Patton Avenue, and I went to work there and stayed here for. I didn't stay on that job, but I stayed in town for four years, and this second house after I had been here for four years and she got a job. She had never been South before, and I stayed to find out whether she was going to be satisfied, and then after the four years was up which we wound up living in a second house down here. I had been living in Asheville, and I moved out here, and she seemed to be satisfied and happy here. And I said, "Well, if you're satisfied, then I don't intend to pay rent. I'm gonna close up and go back and save up money enough because I can make more money up North than I can here and build," and she went along with that all right until I started selling the furniture - she didn't want to get rid of it. I said, "Listen, no need to put stuff in storage when we don't know whether we're coming back cause I'm not coming back until I get enough money to pay for whatever we have, because I don't want an installment plan down here because I could pay half of it and then lose it. I don't want to be no loser. I want to make enough money to pay for it. So, I called the man I bought the stuff from which was name of Green Furniture on College Street. After we decided what we were going to do, I called him and told him what I had in mind, what I wanted to do and I said I would like for you to come out and give me a price on my stuff because I bought it from you and I want you to buy it back. He said "when do you want me to come out?" I said, "Anytime that suits you. He told me when he would come out, and after he told me he was coming I went around from room to room and priced the stuff what I paid and what I ought to get and put it all down in a book. So, when he came, I wasn't there. I was on the job, so the wife showed it to him and he said, "Do you know when your husband want to do this," She said, "I don't know, but the sooner the better." So, he said, "When he comes in tell him I'm ready, come on over to see me." So, I came home that afternoon and she told me what he said. And the next day I went over to see him. He said, "What do you want for it?" and I told him. He said, "When do you want me to come out and get it?" He didn't even change the words. He paid me just what I had priced it for and he sent out to get it. I: How did they deliver stuff like that? C: On a truck, just like they do now. Just load the truck and bring it out. I had everything on the list but the swing and I had the swing on the porch and I left that out. When he come, I said, "Listen that swing was not included, but put it on the truck and take it on and I will tell Mr. Green about it when I get over there. He can just add that to his check." So, then I went on back up North and I stayed then until I was able to pay cash for this little shack. No encumbrance or anything. When the carpenters left here, they had all belonged to them. And I felt free. Then I went out and tried and get a job. Do you know what the first job I was able to land was? $6 a week, that's over on top of the hill there. Now it’s called Appalachian Hall. And I was driving a brand-new Chevrolet car. So, that wasn't paying me to operate that. I worked there about two weeks and the man that was there doing the same work that I was doing before I did it, he came back there and told the manager he wanted his job back, and the man came to me and told me what the man said because I still had my temper. I said he want the job back, he can have it. I'm not making but $6 a week. I said if he can make it with that today. Wait, wait he Cook 10 don't want to start. I won't have it next week no how, and I put on my coat and went out and got in my car. When I got, the car cranked up he came running out. He said, "I'm sorry you feel" I said, "Sorry nothing, hire your man." I came on home. My wife said, "What you doing here this time of day?" I said, "I done quit." She said, "What you gonna do now?" "I'm gonna pack up my things and I'm going over to Fox and Crouts and get me some lumber and make me some shutters and close up the back of these doors." I said, "I'm leaving here." so I left here and went to Pittsburgh. I was there 3 days and I got a job. So, I stayed on that job 3 weeks and got a chance of a better job. I notified the lady and she blew her top. I said, "Now, I'm sorry but you can pay me what I'm gonna get and I'll stay on since if you are so well satisfied and all that, but if you can't pay it, I came here for a job and I didn't come here for a [reputation]. I gave you that and you accepted it but if you can't pay me the money," I'm sorry but it's no responsibility of mine but I got to have the money so I give up and went on to a better job. I: When did you come back to stay? C: I came back here in May of 1933, I came back to stay then and I went to work. There wasn't no jobs worthwhile. I went over to Sears and Roebuck. I knew I could make a living. I knew enough things to do to make a living whether I was employed by any one job or not. I went to Sears & Roebuck, bought myself a brand-new lawnmower, bought myself a lawn chair, everything to take care of the lawn. Put it in the back of my car and I went around from place to place. It was spring of the year, and I went to Grove Park and made solicitation to take care of lawns, cleaning out windows, waxing floors. See all that was in my line. so I did that for two years. Then I began to get offers, and wouldn’t hire for nobody because I was making more money than anybody would pay me. Then after two years one of the places where I was taking care of doing that same kind of work, waxing floors, washing windows, the man's name was Richard Riley, a retired Yankee, decided to buy some property on Cumberland Avenue. These two-great big old brick apartments, they're over there now, with a huge cottage on the front. New York brokers had that property all under mortgage, and I had seen it advertised, and I was already working for him. I said, "You know, this is a sure thing," and he called me in his house one day. He said he had a bid in on his property and he says, "I know I'm going to get it because I'm gonna pay cash for it, and I know they want the money. I'm gonna need a man to take charge of that for me." He said, "The two years that you've been here with me I see you knew what I need and I want you to consider taking it. " Well I studied, I said, "Well, I want to talk with my wife about it first because we've been talking about ... I've been kind of thinking about going on the road again. I'll see what she says and I can let you know in a couple of days." He says, "All right, you do that, becauseI'm expecting this deal to go through. So, I came home that evening. She said, "If you want to try it, we can try it and we can go back anytime." I told her I thought I would try it, so when the deal went through, he called me and told me when and where he wanted me to meet him to talk with the realtor, the man he was dealing with. So, I told him all right. When I met him there, it was a man that knew me quite well, which was old man James Dillard. He was a big realtor down there at that time. He said, "Hello Cook!" He said, "Was this the man you wanted." Riley said, "Yeah this was the man I wanted to get." "Well, you've got a good man. said, "He's all right." He says, "We'll go down." So, they were going to carry me down and show me the buildings. So they carried me on down and showed me Cook 11 buildings and everything was all right. I: What did you have to do? C: Well, I had to ... see each one of those apartments, one sits in one block and the other sits in the next block. And each one of the apartments they have six units. Three apartments . . . the hallway goes straight through the building and apartments on each side. What the janitor had to do there was do the stairway in the back, haul the garbage cans, set on each landing, each stairway in the back. You had to empty those from the third floor down. You had to empty them once a day. The front hall stairways were the same thing. Only it was inside, enclosed. And then in the evenings just before dark you had to put the lights on. Up and down the stairs and the same thing at the back, up and down the stairs. That occurred at each one of the buildings. And then you were free for the rest of the day. So, what I would do would dispense with that, you see I was the house man. I would go to work and finish my work and be through by at least 9:30, not later than 10:00 in the morning. I would be through the rest of the day and all those folks who were able to hire somebody I would go in the house and work the rest of that day, so I stayed there 11 years doing that, see, and after those 11 years were up, I got arthritis. That's what the doctor said it was anyway. I got to where I had to use a crutch. So he told me I had to give that up and so when I notified the lady she was out in the Rockies. So, I had to get in touch with her and let her know. That upset her a whole lot. I had been there just like her husband told her before he passed that you take care of him and I know he's gonna take care of you. I was collecting all the rent and banking all the money, and she didn't have nothing to worry about. I was having all the repairs I couldn't do or didn't do. A tenant would move out and work had to be done. Either I would get somebody to come in or repaint if I wasn't going to do it. She was just having a good time. After she found out she was going to have to give me up, then she said, "You go ahead and make arrangements for getting someone broke in and I will see you when I get home." Well, she came home and she came on over to see me. She said, "You're going to have to go, I'm going to sell this stuff. I wouldn't risk nobody else like I risked you." They would take advantage of me. They wouldn't do like you do, so I'm going to sell it. And I said, "Well I'm gonna have to go." I was on crutches then but I was driving back and forth just instructing the other fellow, anyway I was using crutches. I had to stick with them too because if I got far away from them I had a time getting back to where they were. So, however, I give it up. She sold her stuff and I gave it up and came on home. I was here less than three weeks and the man called me up and said he wanted me to do some work for him. "I'm not working now," I said. "Well, I've been informed about all of that." He says he told about you too, I want to come out and talk to you. You're in a position to do all I want done. I just want somebody to drive. I said, "Well, if that's all you want you can come on out and see me." I was sitting on the porch right out there. He sat down and talked with me. Dr. Givens. He owned 600 acres right here. I know, if you look, you will see Givens Estate right out here. And he owned all that land in there then and he said he just wanted somebody to drive. So, I told him I would try it. So, I did. And he's passed on and since he passed, his wife has passed, and all that's been willed to some kind of home, and that's what they've got out there now. That's that part of it. So, I'm still around here kicking. Cook 12 I: When did you first ... it sounds like you did a lot of going back and forth up North, … when did you first settle into this community? C: I started regularly with NAACP in 1935 or '36 when I started working with them. I: What made you see the need to do that? C: At that time, you see, there was a struggle followed by some of my traveling experiences led me to see into a lot of privileges that we were being denied of. And this organization that's what it was working for - equal rights for everybody. I: In your travels, you could see C: I just thought, well now it's for me to render the service that I can render to help this organization along. Mr. Steward I: And this was in 1935? C: Yeah, Mr. Steward, well this was earlier than that. Mr. Steward was a member of Nazareth and he was a great worker with NAACP and he asked me about it. He said I think you ought to go join. And they worked out here at Hickory Nut Gap. James Clark McClure. I know you've heard about him. He had been there for years. And they got after me too. He was treasurer at that time, so soon after I got in, then the group saw it necessary that they wanted me to be the treasurer. That's why I was elected treasurer. In other words, the group as it began to get larger and larger, I think. I: How many members were in it when you started? C: When I started, wasn't over 25. As it began to get larger, they began to think in terms, they were thinking that things wasn't operating like they should, financial-wise, so that's why we wanted to make changes. Mr. W. C. Allen, who was an undertaker here at that time. They elected me as treasurer and they didn't have money in the bank. I said, "I want the money put in the bank." I said, "I want it to be signed by the president and secretary and the money has got to be deposited." I started in with a bank account. Up until that time they hadn't had no bank account at all. I: Who were some of the other people - you said there were 25 at the beginning. C: Mr. Steward, Mr. W. C. Allen, Mrs. L. B. Michael, and Mr. W. R. Saxton, Mr. Luther Thomas, Mr. and Mrs. John Shorter, Eugene Smith, J. R. Swindle, Leonore Reed, Mrs. Frances Owens those were the main ones that really had a hand in it, ongoing. I: What were some of the focuses, what were some of the things that they wanted to accomplish? Cook 13 C: Well, one of the main issues, the first thing they started up, one that I had a hand in, was trying to get Black policemen. See, there wasn't any Black cops at all, wasn't nothing but White cops. So, we took that issue and for three years Mrs. L. B. Michael, Mr. Luther Thomas, W. R. Saxton, we met City Council every Thursday. That's when they met, on Thursday, to see what we could do about getting some Black policemen. So, after the period of the second year, two or three of them started getting cold feet and wanted to give up, thought we wasn't going to get them. So, I told them this, "No, let's don't give up." I said, "as of now they haven't told us one time that they wasn't going to give em to us. Let's keep on knocking," and I said, "after a while…” I: What were you all doing? C: Well, we would just relate to them what we felt the necessity of some Black officers. I said, "they haven't told us now that we weren't going to get them." I said, "just keep on trying. If they give us a denial, then that would-be time to stop. After while they're going to get tired of us and they'll break down and give them to us." So, that's what happened, they got tired of seeing us. I said, "they'll get tired and they'll give them to us." So, that's what happened. First ones that were appointed was a fellow that lived in West Asheville. We got a fellow, Horne, was the first one and then the next one after Horne came a fellow a Flemmings guy. And then after they got on, poor fellow he's gone to the Lord too. Dr. Hendricks, he put a piece in the paper and the indication of that led up, what he was saying, that the folk was just good enough to give them to us because we needed them, but you see, it wasn't that. He didn't give us any credit and hadn't give us any credit for what we've done for three years we've been making that sacrifice but that was all left out and then our group wanted to put in a complaint about everybody. I said, "No, we're not gonna make no rebuttal." I said we got what we wanted. We made that accomplishment and they want to put it in the paper that it was the goodness of them to give them to us. We've got them. They're there, and that was what we wanted and so that was it. I've made several statements since then in the NAACP meetings that that's what happened. Not too many months ago we had a group down there that when we got ready to put in this suit that we've got now, I said "they don't even know why they're there. But they're there." It came from sacrifice they don’t know anything about. We had a group down there not long ago of city employees that's before we got ready to put this through here. I: To work back then, when I asked you what Asheville was like. I know it was segregated, but what kind of effect did that have on you personally? How did that make you feel? C: Well, having known about it, one thing about it, having gone other places and seen things you know are not going to work, if you know how you're going to feel about it, you won't go into it. In other words, if, for example, there's a door and I know I'm not supposed to go in, I'm going to go in anyhow because I know the trouble it will create. I know my temper, so I stay out of it to avoid trouble and you just try to eliminate those things that you know are going to cause frictions. Cook 14 I: But you have been places and seen it done different so you had indications that it could be better here. C: Absolutely. I: Has the NAACP changed any over the years? C: Well, no, it has just gotten to the point now where it knows it's in position to do things it one time couldn't do. Of course, it feels more that the laws has changed and gone in our direction, and to let us know we're entitled to do more and stay within the laws, than what a lot of them wants us to do. Like it is now, there's lots going on now that the majority may be against it but the law said you couldn't do anything about it. So, it's just one of those kinds of things and that's been brought about by the NAACP and other organizations just like Martin Luther King has done, broken the barriers down and we know those things has happened and we go along with it. But there's a lot of folks still don't want it. You know where you got money to sit down and get a meal, you can get it, but a lot of them don't want it but you can go get it anyway and you won't be violating the law. The law says you can do it. You can order you a seat in a plane or a train or any place you want to if you've got the money. I: There was the time when you had the money and couldn't do that. C: That's right. No matter how much money you had. I: Now taking you back, when you were little and did you go to church? C: Oh yeah. I've always gone to church. Everywhere I've ever been. I: Has the church changed any? Are the customs still the same in your church or are they different? C: They're just about the same because the thing about the customs in the church, people as a rule have a tendency to follow the trend and they might lean toward that trend whether it's in harmony with what you would like to have or not. There are a lot of things that go on in churches now that 30 years ago it wouldn't be. It's in my church the same way. We have things that go on there ... I: Give me an example. C: Well, they have been a time at my church when certain things that go on in the pulpit now wouldn't be thought of in the pulpit back 40 years ago. You take the last two, pastor we got now, conditions are worse and the pastor before him when he first came it was different from what it was when he left. He stayed there 26 years though. The pastor that was there when I joined in 1925 which was in August, those rules and regulations, they weren't allowed to govern the church and the church's routine. There's none of that in effect now. There's none of it. It's Cook 15 all different. You had to have certain qualifications to step up in the pulpit. You weren't allowed. You didn't do it. All you got to do now is just go up there. It's just follow the trend. You take some of these men, I don't know if all of them do it, I can only talk for my church. You can go out down east. You can have a big crap game and somebody see you with it and know you got it. If somebody wants you up in the pulpit you can go up in the pulpit and make an announcement, anything you want to. They have no standards and no records. I sit down in my church a lot of times and see things go on that shouldn't be, but no need to say anything, it don't do no good to talk about it as long as it's all right with the head authorities. I: So, you think it's been a big change? C: Oh yeah. I: Do you remember any holidays or any heritage things, holidays for example, that Black folks celebrate that other races didn't, like I've talked to a lot of people that remember something called June 10th? an Emancipation Day celebrated in Texas. Juneteenth. C: Well, in this area around Asheville here, I haven't heard so much about the emancipation celebration. But you take down in South Carolina, the emancipation celebration used to be a big thing. I: When was, it held? Do you remember what month? C: I don't know what month it was. Was it October or November (speaking to another person in the room), do you remember when they used to celebrate emancipation? That's right, the Fourth of July. Unknown: [inaudible] Unknown: During the 50's and 60's we were involved in that. We used to meet up on Market St. on Tuesday and Wednesday afternoon. There was a group of us that participated. There used to be an A&P or a Winn-Dixie on College St. and we picketed that Winn-Dixie and, I was wondering how the leaders or people involved with NAACP at that particular time felt about it back in the 60's. To get anywhere, we have to go out and show them we can stand up to them and Black power, that's what it is now. We have to do it that way. Forget the nonviolence routine, I just wondered how you felt about that at that particular time? C: Well this branch here, you see we picketed several places here and the last one we picketed was one on Carter right across from the Courthouse here. Mr. McCoy. That’s the last one we picketed. We thought it was necessary, something should be done. And of course, you felt the same way if you take our state president, which was Kelly Alexander at that time. They also went in for that and his son also, he's president now, when it was necessary. They believe in picketing now, when it is necessary. Of course, now they are taking on issues to try out things now before doing that because they're calling all these big companies and these big grocery Cook 16 stores. We have committees to go around and call on them and see, getting their consent about their doing this and their doing that. In order to eliminate that kind of stuff and we have gotten papers signed from different companies, like these chain stores and things like that promising NAACP that they will take on so many employees during the year. We know for your trade, for your business, we got large Black businesses down in our store and you got it in your company. We don't see where you got nothing like equal employment among the races in your store, now we want to know about you taking on some colored cash registers and some colored stockroom men. If you don't, we want to know the reason why and if we send you somebody qualified will you employ them? If you can't do it, we would just as soon picket your place. You take Bi-Lo, they already signed the papers and it’s in our offices with their promise to give so many jobs to Blacks in the Bi-Lo Company throughout different places. The last one they were discussing was Ingles. But they've got some. What they do after they're called on. We send these committees out. You watch it. You see why they haven't signed the papers. You might see different ones in on it along the line. I noticed that they have several Blacks over here at this Ingles on Henderson Road. I: What happened to Black businesses after integration? C: Well, we ain't got no real Black businesses going on here in Asheville of any account. I: But what… the argument as put forth now that the NAACP didn't understand integration, that integration had to be fair or equal, in other words we integrated with them. They didn't integrate with us. In other words, they never came over to our businesses. They never came to our cleaners. They never came to our restaurants. They never came to anything we had. We integrated with them. We went to their restaurants, we went to their stores, we went to their schools. So, it was unfair. Now a lot of people ... you begin to hear this and I hear [Hooks] having a hard time with that question. Unknown 1: Can I answer that question? We don't have nothing to offer the White man. We don't have no businesses of our own and everything we get we have to go to the White man to get it. The White man always got something we want. But, what have we got that they want. But when it comes down to the business, we don't have it. Them that's got it don't care enough about it to keep it up. You have to keep it up. [inaudible] Unknown 2: Doesn’t it come from the home? Unknown 1: That’s what I’m saying, you can’t get the mothers and the fathers to go to no meetings that we have. We had a meeting Thursday night and all of the parents in the community was notified to be there. They won’t come across the street. We need to get up off our lazy, you know what ... Unknown 2: You see what has happened now, the Blacks have gotten more complacent. Cook 17

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Zenophon B. Cook is interviewed by Edward Clark Smith June 28, 1987 as a part of the Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project. Born in 1900, Cook moved to Asheville in his teens to work at the Battery Park Hotel, then went to automotive school in Cincinnati, Ohio and became a chauffeur. He settled in Asheville in the mid-30s and got involved with the local NAACP. One of the first major goals they accomplished was getting a Black police officer hired on to the police force. Cook talks about picketing for equal employment, his feelings on segregation and desegregation, racial inequities, and the church.

-