Western Carolina University (21)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- George Masa Collection (137)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (3080)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (422)

- Horace Kephart (973)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (89)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (318)

- Picturing Appalachia (6617)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (153)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1463)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (67)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

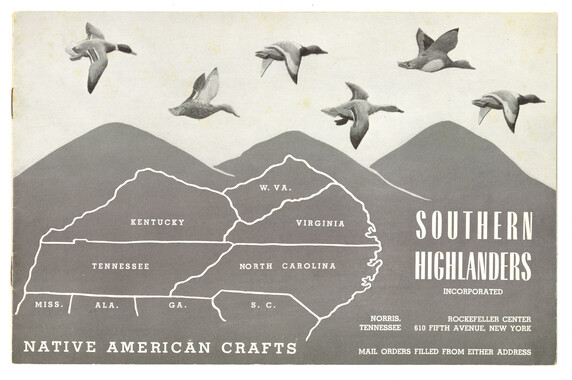

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (2008)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (3032)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1945)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (195)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1680)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (556)

- Graham County (N.C.) (238)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (525)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3573)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4925)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (35)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (13)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (421)

- Madison County (N.C.) (216)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (135)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (982)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (78)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2185)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (86)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (192)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (3)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Digital Moving Image Formats (2)

- Drawings (visual Works) (185)

- Envelopes (101)

- Exhibitions (events) (1)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (823)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1045)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (6090)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Notebooks (8)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (194)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12977)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (6)

- Portraits (4568)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (181)

- Publications (documents) (2444)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Relief Prints (26)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (1)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (802)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (18)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (329)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (462)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1482)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (36)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1923)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (190)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (111)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (2012)

- Dams (108)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (63)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1198)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (47)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (122)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (9)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (72)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

Western Carolinian Volume 68 Number 04

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

NEW MONTHLY FEATURE: Miniature Provides Emotional Link to the Fallen Towers By Benjamin Forgey I The Washington Post In 1962, when he was being considered for one of the biggest architectural jobs of the 20th century—designing the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan—Minoru Yamasaki composed a letter to the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. "If we should be so fortunate as to receive the commission," Yamasaki wrote, "we would build a large scale model of the entire neighborhood surrounding your complex in sufficient detail to enable you and us to understand exactly how various schemes would relate to the surrounding area." Yamasaki got the job and, as it turned out, he and colleagues in his Michigan studio built more than a hundred models of the project, testing different design ideas. Only one of those models still exists. Painstakingly restored, it went on view Thursday in a darkened chamber at the American Architectural Foundation's Octagon Museum. The sight is quite striking. The visitor turns a corner at the second-floor landing of the Octagon's elegant 18th- century stairwell, enters the room on the right and comes face to face with the spotlighted twin towers—stark white forms on a pedestal in a plexiglass box. The shrinelike setting is at once odd and oddly appropriate. It is strange to see an architectural model treated almost like a religious icon. Yet it feels right in the aftermath of the trade center's awful destruction two years ago. In the only slightly exaggerated words of Ronald Bogle, president of the American Architectural Foundation, the model before your eyes is "all that remains of the World Trade Center site in its original form." From the beginning, this model was intended to knock socks off. It was created toward the end of the design process, after Yamasaki and his team had made all the key decisions about the shape and form of the office towers, the four lower buildings in the complex and the great plaza on which they all would stand. Known as a presentation model, this probably was the largest and last of the three-dimensional versions of the project the Yamasaki folks turned out. The Port Authority later commissioned another, similarly detailed model for display in the lobby of one of the towers, but, of course, it was lost in tons of rubble on Sept. 11, 2001. The other Yamasaki models, explains Octagon Museum Director Sherry Birk, were primarily for study and were dismantled or lost over the years. The main purposes of the large Yamasaki model was to wow potential tenants or calm opponents at various public hearings. To aid in these missions, the architects enlisted photographer Balthazar Korab to make a series of staged photos showing how the buildings would look, in the "real" setting of Lower Manhattan. Forty of Korab's astonishingly realistic photographs also are on view; their enchanting deceptions are particularly remarkable given their origin in pre-digital days. But the exhibition's stunning focus remains the big model. Built on a scale of one inch to 16 feet, it is splendidly detailed. Little cars in bright 1960s colors travel the streets. Bright little people walk the sidewalks and stroll across the plaza. The twin towers are seven feet tall, and they seem delicate in a way that the real buildings never did except from a great distance. This reminds you that, in fact, the enormous towers always looked best from a distance: They were mighty landmarks that sparkled when seen from Brooklyn in the morning sun, and shimmered softly above the Hoboken ridge when glimpsed at dusk from the Jersey side. It was the width and depth«of !hose Aluminum-sheathedwerticals„that engaged the sum Üp.aoÅéÅfiGse endless 18-inch•wQie columns were not so enticing. PULL„OUT SECT}ON MUSEUM WTC: The only remaining architectural model of the twin towers is "all that remains of the World Trade Center site in its original form," says an official at Washington's Octagon Museum, where the model is on display. Photo by Marvin Joseph 0 2003 WASHINGTON POST The buildings' great height and minimalist shapes also appeared to best advantage from far away. Making two of the same was one of Yamasaki's best and most important choices—the relationship of the great rectangles changed constantly as one moved about the city. Walking slowly around the model, you can re-create something of this dynamic effect. What you cannot re-create is the experience of being in the five-acre plaza. It looks neat and pretty in model form, but in actuality it was too big and almost scaleless. Yamasaki compared it to the Piazza San Marco in Venice, but it didn't turn out that way and, looking at the model, you can see why. Built on a platform, the whole complex was separated from its immediate urban neighborhood. Examining the model carefully, then, is a useful as well as a moving exercise: There are mistakes we don't want to make again, in rebuilding the place. (Fortunately, architect Daniel Libeskind's competition-winning proposal is a pretty good start.) Yet the most interesting thing about the model is its sense of confidence and even serenity. Yamasaki and the others didn't know they were making some big planning mistakes, for they were working within a flawed urban redevelopment system that had been operating in American cities for more than two decades. And they certainly did not foresee that the towers would become deadly targets. Rather, they saw themselves doing what needed doing, only on a bigger and better scale than before. This model was an important cultural artifact even before Sept. 11, 2001, but the events of that day have raised its value immeasurably. Credit is due the Octagon Museum for saving it, in the first place, by seeking out the Yamasaki firm in the early 1990s. A public-private coalition—including the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the American Architectural Foundation, Save America's Treasures and Alcoa (maker of the original aluminum alloy)—made possible the first-rate restoration of the mode(.e , 0 2003 WASHINGTON post

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

The Western Carolinian is Western Carolina University's student-run newspaper. The paper was published as the Cullowhee Yodel from 1924 to 1931 before changing its name to The Western Carolinian in 1933.

-