Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (292)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2766)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1388)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

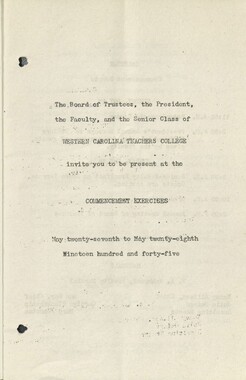

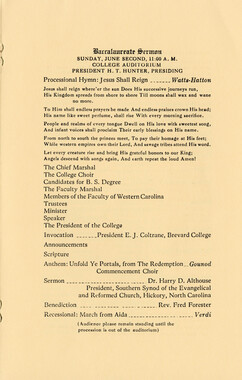

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (1794)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2569)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1923)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (161)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1672)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (233)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (519)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3524)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4694)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (25)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (12)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (212)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (981)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2115)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (84)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (184)

- Envelopes (73)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

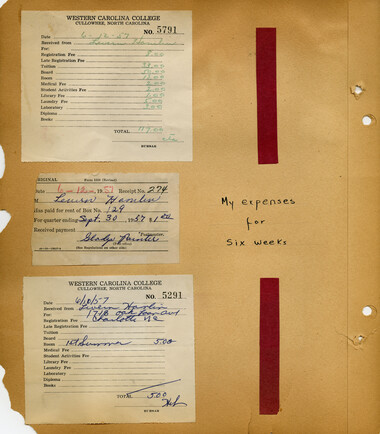

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (815)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (5835)

- Newsletters (1285)

- Newspapers (2)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (6)

- Portraits (4533)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (151)

- Publications (documents) (2236)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (15)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Vitreographs (129)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (282)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

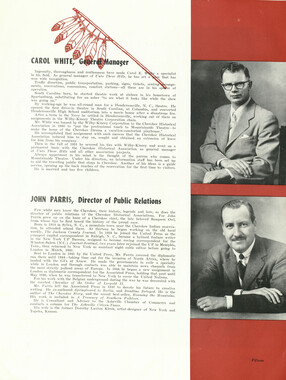

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1407)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1744)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (170)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (110)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (1830)

- Dams (107)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1184)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (38)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (118)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (71)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (244)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

Levern Hamlin scrapbook

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

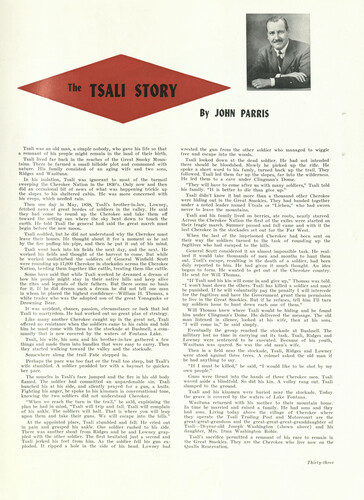

By JOHN PARRIS Tsali was an old man, a simple nobody, who gave his life so that a remnant of his people might remain in the land of their birth. Tsali lived far back in the reaches of the Great Smoky Mountains. There he farmed a small hillside plot and communed with nature. His family consisted of an aging wife and two sons, Ridges and Wasituna. In his isolation, Tsali was ignorant to most of the turmoil sweeping the Cherokee Nation in the 1830's. Only now and then did an occasional bit of news of what was happening trickle up the slopes to his sheltered cabin. He was more concerned with his crops, which needed rain. Then one day in May, 1838, Tsali's brother-in-law, Lowney, fetched news of great hordes of soldiers in the valley. He said they had come to round up the Cherokee and take them off toward the setting sun where the sky bent down to touch the earth. He told Tsali the general had said the great march must begin before the new moon. Tsali nodded, but he did not understand why the Cherokee must leave their homes. He thought about it for a moment as he sat by the fire puffing his pipe, and then he put it out of his mind. Tsali went back into his fields the next day, and the next. He worked his fields and thought of the harvest to come. But while he worked undisturbed the soldiers of General Winfield Scott were rounding up 17,000 Cherokee in stockades across the Cherokee Nation, herding them together like cattle, treating them like cattle. Some have said that while Tsali worked he dreamed a dream of how his people might stay in their native hills and keep alive the rites and legends of their fathers. But there seems no basis for it. If he did dream such a dream he did not tell one man in whom he placed the highest confidence—William H. Thomas, a white trader who was the adopted son of the great Yonaguska or Drowning Bear. It was accident, chance, passion, circumstance or luck that led Tsali to martyrdom. He had worked out no great plan of strategy. Like many another Cherokee caught up in the great net, Tsali offered no resistance when the soldiers came to his cabin and told him he must come with them to the stockade at Bushnell, a community that is now covered by the waters of Fontana Lake. Tsali, his wife, his sons and his brother-in-law gathered a few tilings and made them into bundles that were easy to carry. Then they started walking toward the valley and the stockade. Somewhere along the trail Fate stepped in. Perhaps the pace was too fast or the trail too steep, but Tsali's wife stumbled. A soldier prodded her with a bayonet to quicken her pace. The muscles in Tsali's face jumped and the fire in his old body flamed. The soldier had committed an unpardonable sin. Tsali bunched his at his side, and silently prayed for a gun, a knife. Fighting his anger, he spoke to his kinsmen in conversational tone, knowing the two soldiers did not understand Cherokee. "When we reach the turn in the trail," he said, explaining the plan he had in mind, "Tsali will trip and fall. Tsali will complain of his ankle. The soldiers will halt. That is where you will leap upon them and take their guns. We will escape into the hills." At the appointed place, Tsali stumbled and fell. He cried out in pain and grasped his ankle. One soldier rushed to his side. There was another shout from Ridges and he and Lowney grappled with the other soldier. The first hesitated just a second and Tsali jerked his feet from him. As the soldier fell his gun exploded. It ripped a hole in the side of his head. Lowney had wrested the gun from the other soldier who managed to wiggle free and escape into the woods. Tsali looked down at the dead soldier. He had not intended there should be bloodshed. Slowly he picked up the rifle. He spoke a short word to his famly, turned back up the trail. They followed. Tsali led them far up the slopes, far into the wilderness. He led them to a cave under Clingman's Dome. "They will have to come after us with many soldiers," Tsali told his family. "It is better to die than give up." Tsali didn't know it but more than a thousand other Cherokee were hiding out in the Great Smokies. They had banded together under a noted leader named Utsala or "Lichen," who had sworn never to leave the mountains. Tsali and his family lived on berries, ate roots, nearly starved Across the Cherokee Nation the first of the exiles were started on their tragic march. Summer passed and fall came and with it the last Cherokee in the stockades set out for the Far West. When the last of the imprisoned Cherokee had been sent on their way the soldiers turned to the task of rounding up the fugitives who had escaped to the hills. General Scott considered it an almost impossible task. He realized it would take thousands of men and months to hunt them out. Tsali's escape, resulting in the death of a soldier, had been duly reported to him. He had given it much thought. An idea began to form. He wanted to get out of the Cherokee country. He sent for Will Thomas. "If Tsali and his kin will come in and give up," Thomas was told. "I won't hunt down the others. Tsali has killed a soldier and must be punished. If he will voluntarily pay the penalty I will intercede for the fugitives and have the Government grant them permission to live in the Great Smokies. But if he refuses, tell him I'll turn my soldiers loose to hunt down each one of them." Will Thomas knew where Tsali would be hiding and he found him under Clingman's Dome. He delivered the message. The old man listened in silence, looked at his wife, then at his sons. "I will come in," he said simply. Eventually the group reached the stockade at Bushnell. The military lost no time in carrying out its task. Tsali, Ridges and Lowney were sentenced to be executed. Because of his youth, Wasituna was spared. So was the old man's wife. Then in a field near the stockade, Tsali, Ridges and Lowney were stood against three trees. A colonel asked the old man if he had anything to say. "If I must be killed," he said, "I would like to be shot by my own people." Guns were thrust into the hands of three Cherokee men. Tsali waved aside a blindfold. So did his kin. A volley rang out. Tsali slumped to the ground. Tsali and his kinsmen were buried near the stockade. Today the grave is covered by the waters of Lake Fontana. Wasituna returned with his mother to their mountain home. In time he married and raised a family. He had sons and they had sons. Living today above the village of Cherokee where they operate the Tsali Trading Post and Motorcourt are the great-great-grandson and the great-great-great-granddaughter of Tsali—73-year-old Joseph Washington (shown above) and his daughter, Mrs. Irma Washington Robie. Tsali's sacrifice permitted a remnant of his race to remain in the Great Smokies. They are the Cherokee who live now on the Qualla Reservation. Thirty-three

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

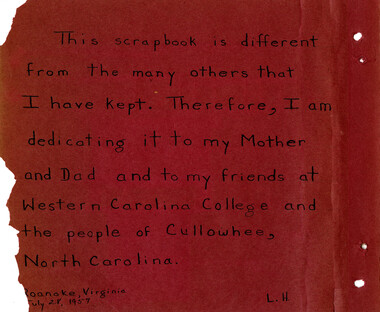

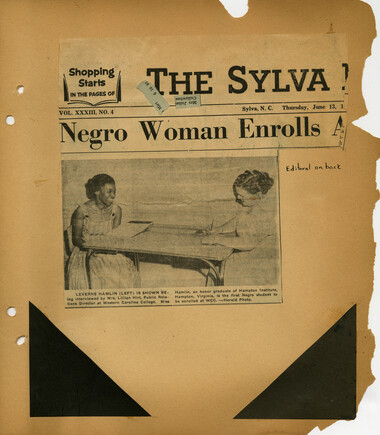

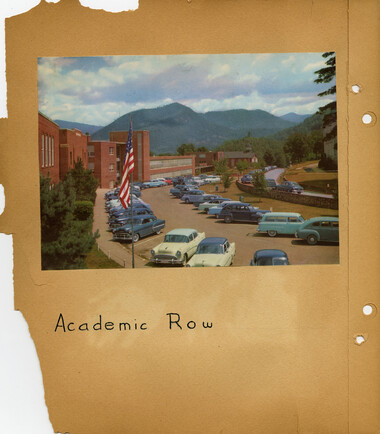

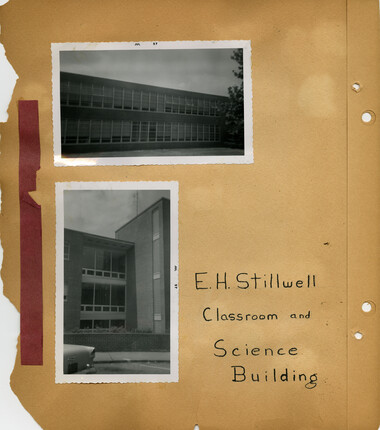

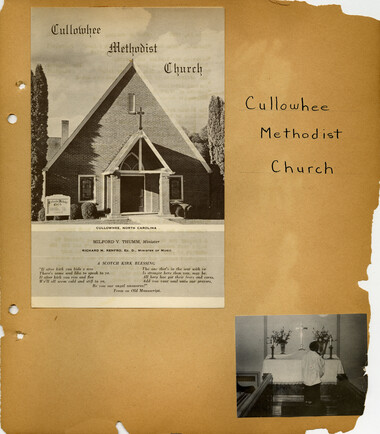

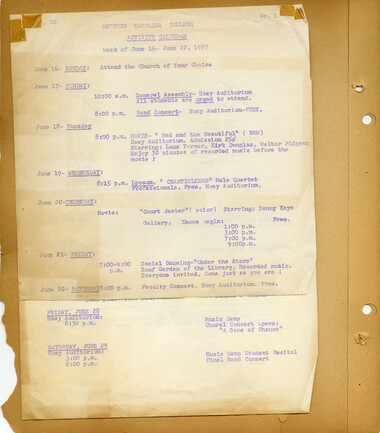

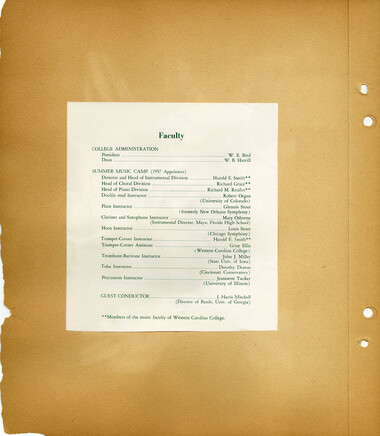

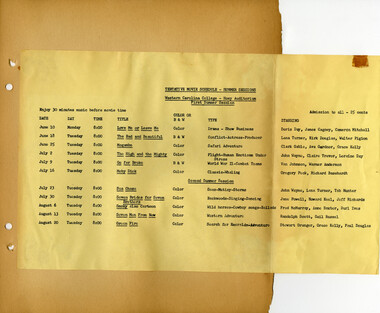

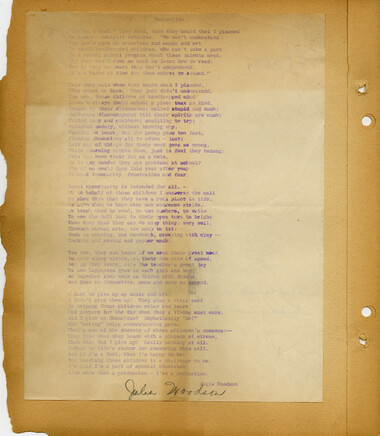

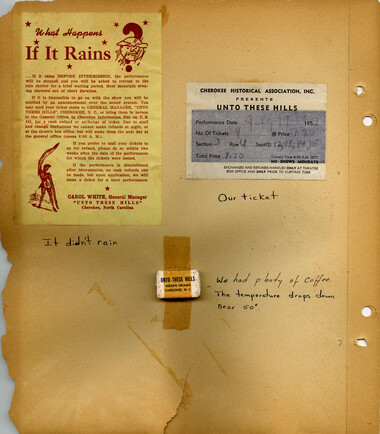

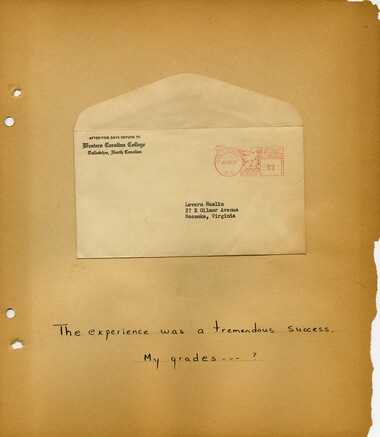

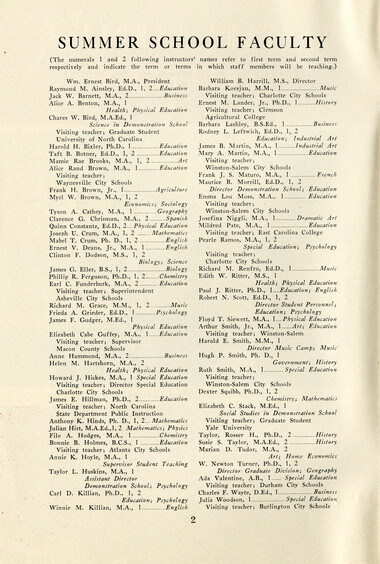

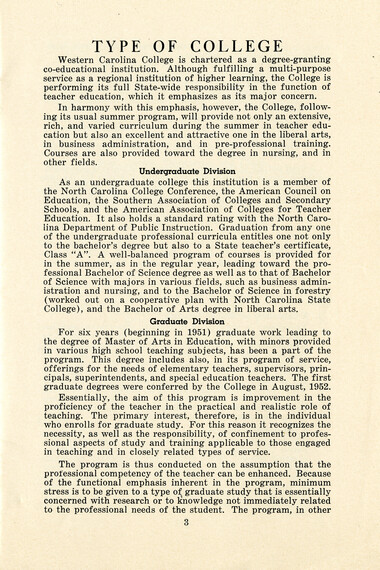

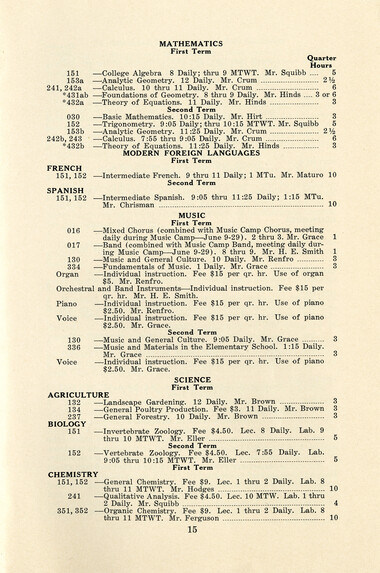

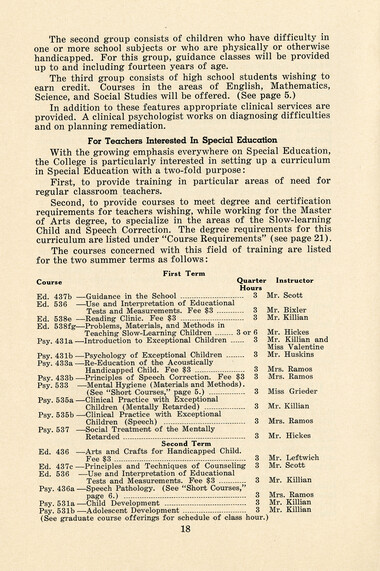

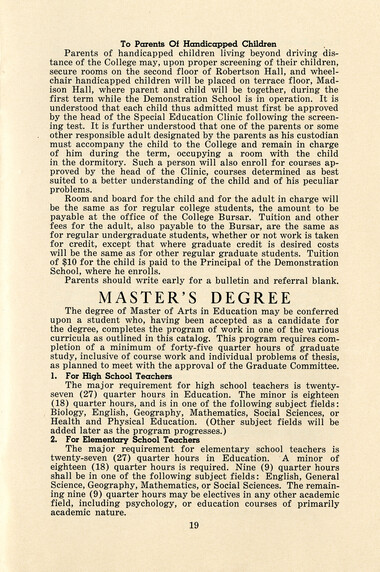

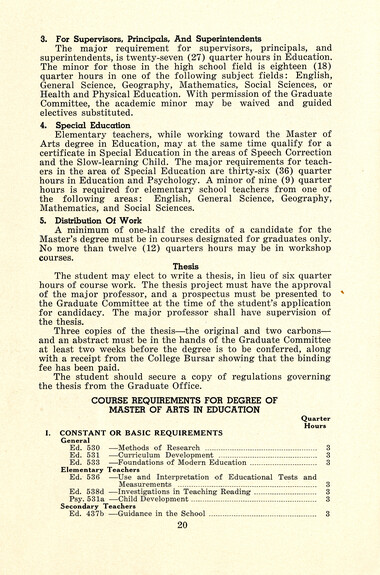

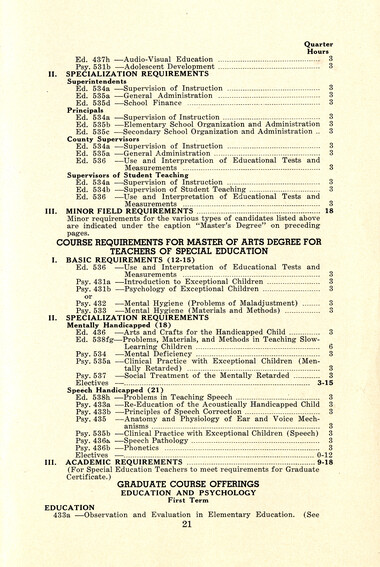

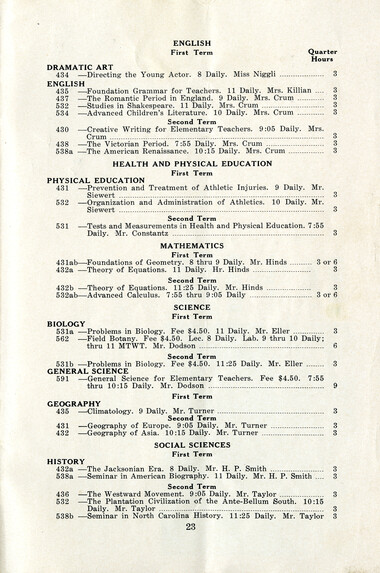

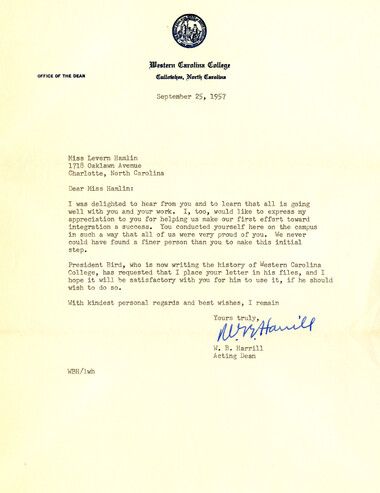

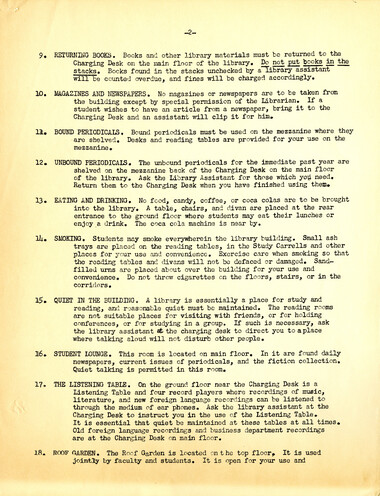

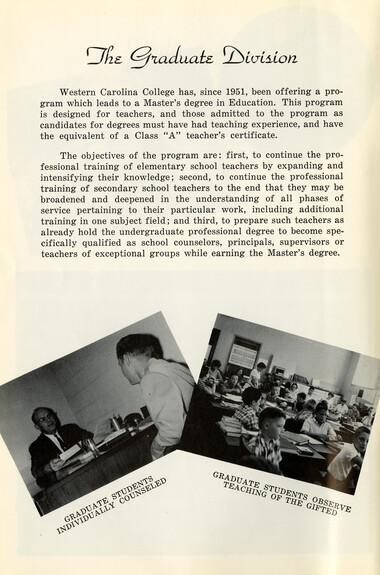

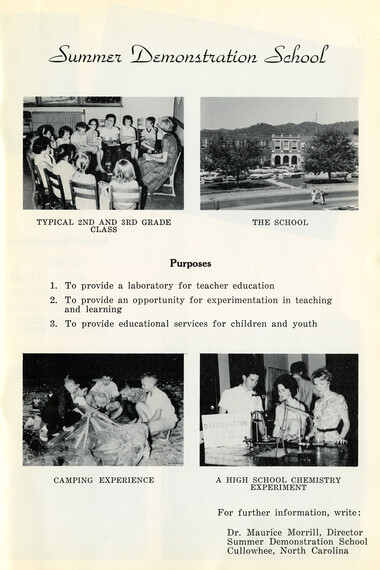

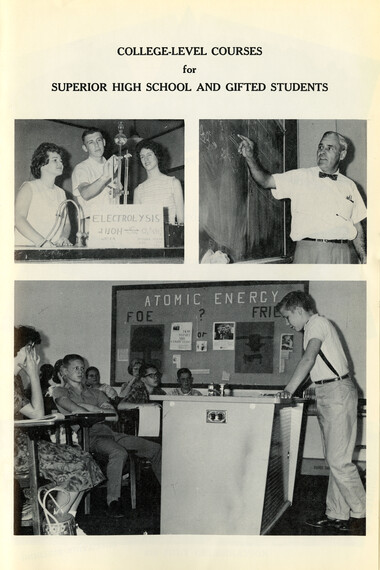

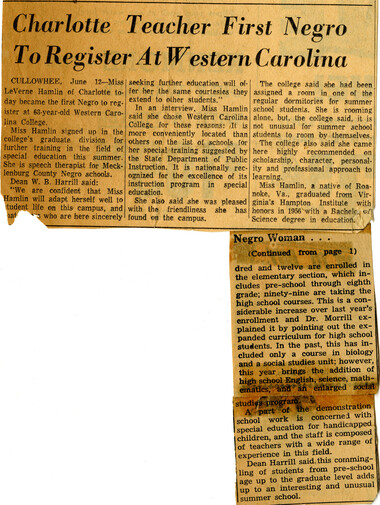

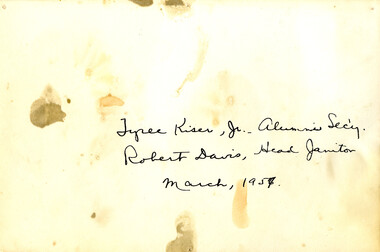

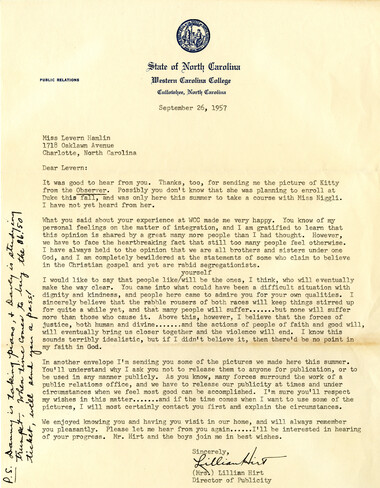

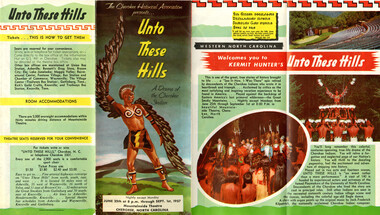

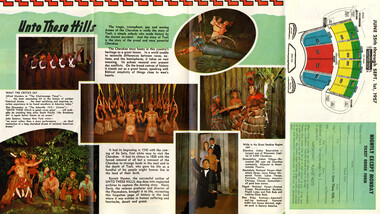

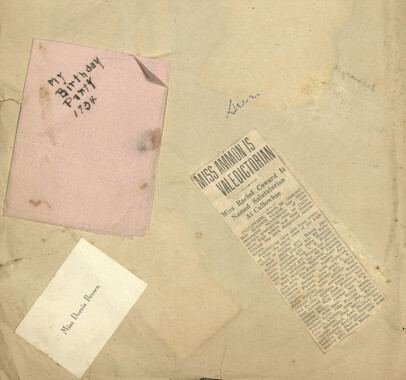

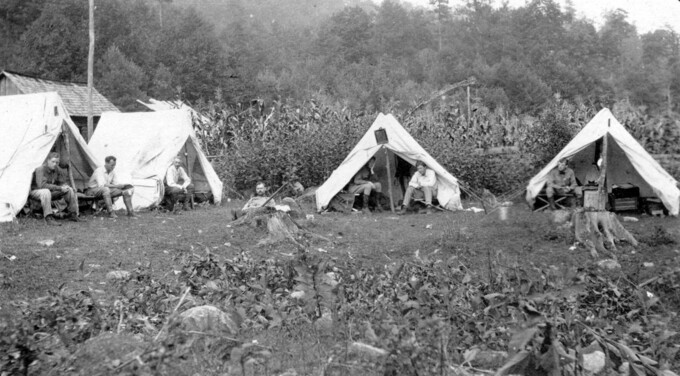

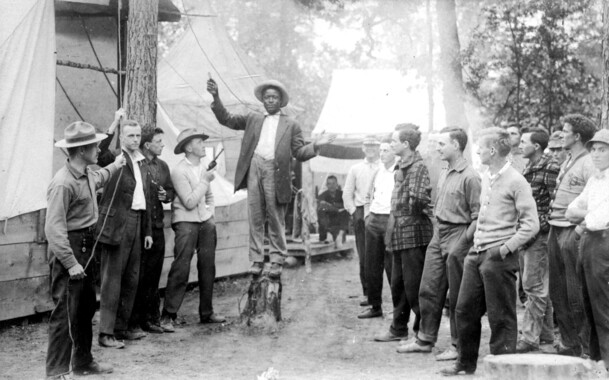

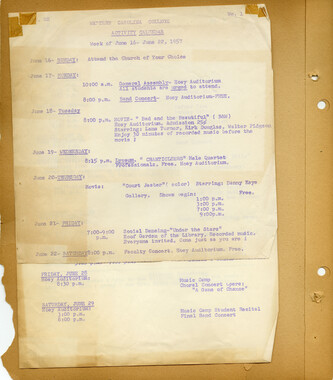

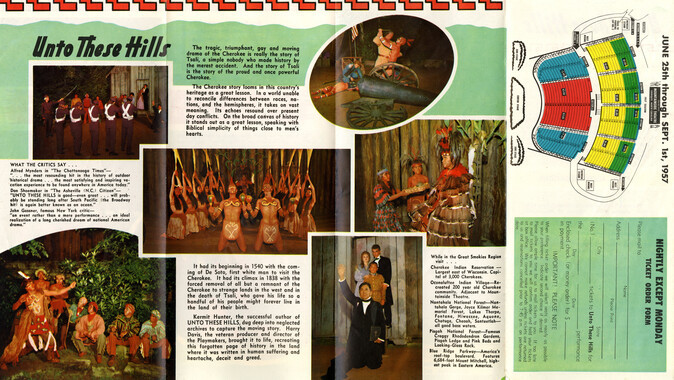

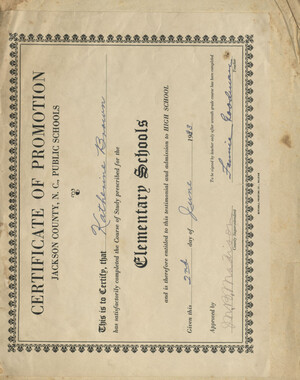

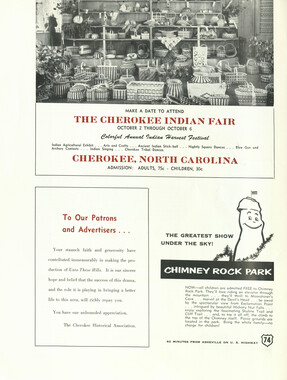

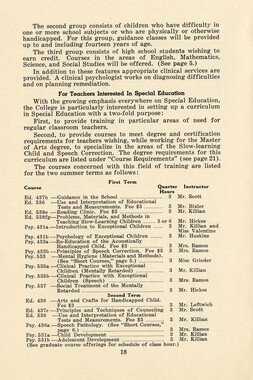

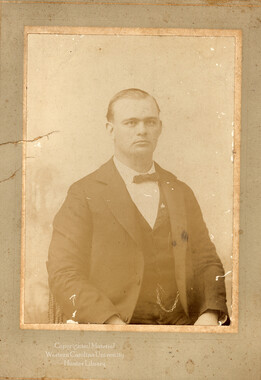

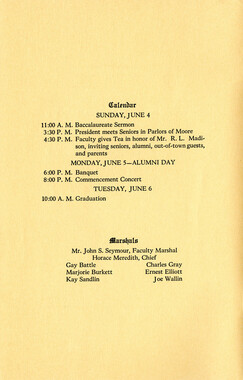

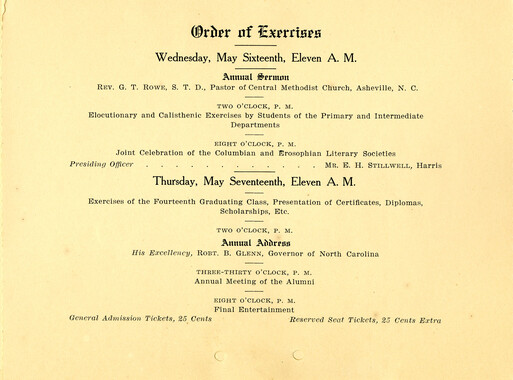

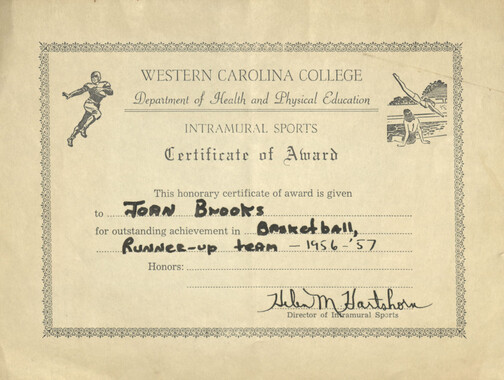

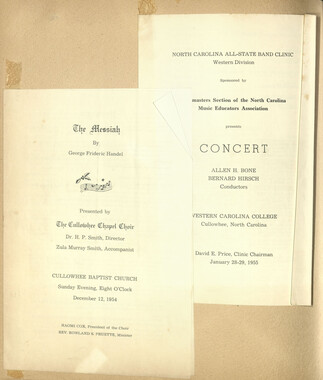

This 42-page scrapbook was put together by Levern Hamlin, a Roanoke, Virginia native who moved to Cullowhee, North Carolina in 1957 to attend Western Carolina College. Levern Hamlin was not only the first African American to attend Western Carolina College but the first African American admitted to a North Carolina state college. As a speech therapist practicing in Charlotte, North Carolina, Hamlin decided to further her training in special education through the college’s graduate division. The scrapbook begins with Hamlin’s account of her arrival at WCC on June 11, 1957 and includes numerous clippings describing the significance of her enrollment. The scrapbook contains entries from her summer semester at WCC extending to July 20th, 1957 when she arrived back at her home in Virginia. Hamlin had previously attained a Bachelor of Science degree in education from Virginia’s Hampton Institute in 1956. Also included are pamphlets and clippings at the end of the scrapbook.

-