Western Carolina University (21)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- George Masa Collection (135)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2901)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (422)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6798)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (153)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1463)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

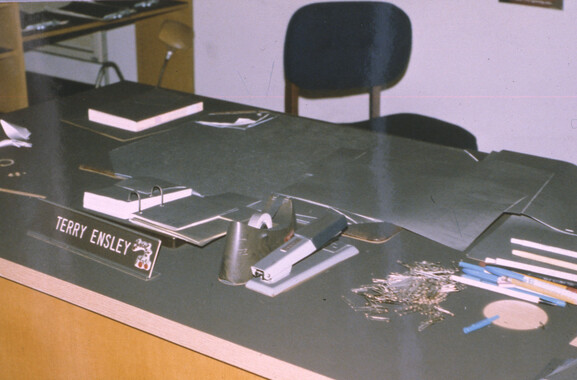

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

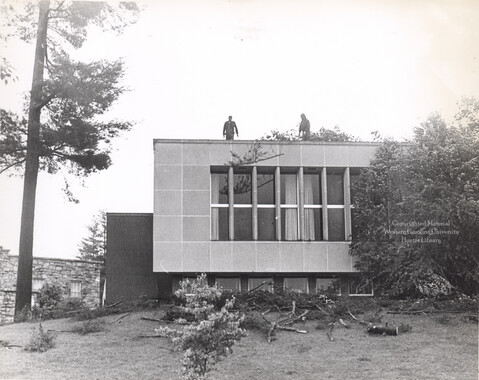

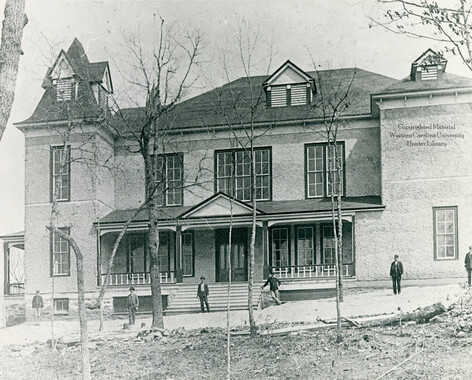

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (2008)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2693)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1936)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (195)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1672)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (556)

- Graham County (N.C.) (236)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (519)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3569)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4913)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (35)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (13)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (215)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (982)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2182)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (86)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (3)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (185)

- Envelopes (73)

- Exhibitions (events) (1)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

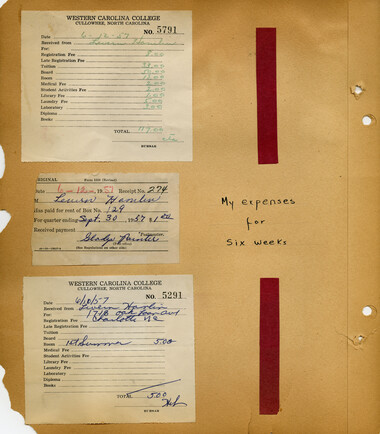

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (815)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (6090)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Notebooks (8)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (5)

- Portraits (4568)

- Postcards (329)

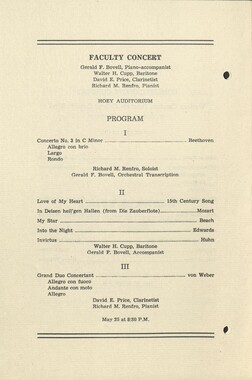

- Programs (documents) (181)

- Publications (documents) (2443)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Relief Prints (26)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (1)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (18)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (462)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1482)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1923)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (190)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (111)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (2012)

- Dams (107)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1195)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (45)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (119)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (72)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

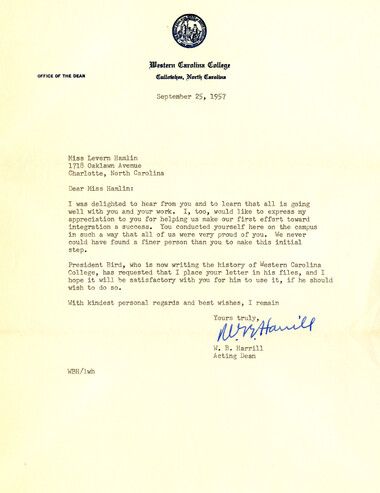

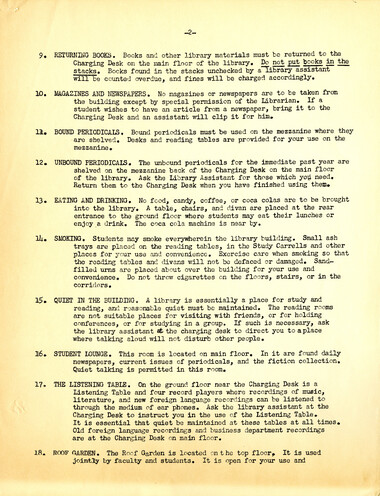

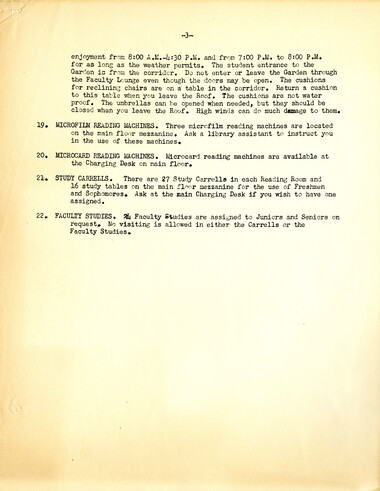

Levern Hamlin scrapbook

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

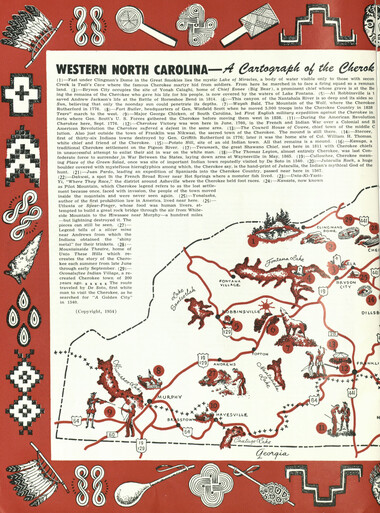

he frail of Tears The Road 17,000 Cherokee Indians plodded into exile more than a hundred years ago winds 1,200 miles through the heartland of America from North Carolina to Oklahoma. Today it is a road of hope and promise, but in 1838 it was a road of misery and heartache, sickness and death. To students of history it is known as "The Trail of Tears." A proud nation, uprooted and dispossessed, traveled it for six long, bitter months in 1838-39. Sickness broke out at every mile. One person out of every four died on the forced march. The humiliation and suffering which the Cherokee experienced on that sorrowful march have no parallel in American history. To recapture that black, forgotten page, the Cherokee Historical Association in May 1951 sent an expedition out over the old trail. Four Cherokee tribal leaders headed the group that made the trip through North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas to Oklahoma. The story of that march into exile a hundred years ago and its cause forms one of the darkest chapters in the history of American empire building. The Cherokee were forced on to that tragic trail after years of trying to hold out against white encroachment upon their lands, years which were filled with deceit and greed and strewn with broken treaties. Their downfall was inevitable with the coming of the first white man, Hernando De Soto in 1540, but it was not until 1815 with the discovery of gold on their land that their doom was sealed. With that discovery their enemies moved quickly to rout them from the coveted land. A treaty was signed in 1817, approved by President Thomas Jefferson, providing for removal of the Cherokee to the West. Rage swept the majority of Cherokee chieftains when they learned of the pact, signed by a minority group, which would have paid each man the handsome sum of forty-two dollars. "The agreement is not the voice of our people," they cried. "It is a fraudulent breach of trust." They declared that the majority of the Cherokee desired to remain in the land of their birth. But the die had been cast and was not to be broken. Finally, after years of bickering and fighting, it was agreed the Cherokee should be paid $5,000,000 for their lands. General Win- field Scott was named to force the removal. The general, commanding 7,000 troops, moved into the Cherokee country in May. 1838, and began disarming the Cherokee. Stockades were built under Scott's orders at various points in North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee and Alabama. Into them were herded the Chreokee. From the stockade garrisons, squads of troops were sent to search out with rifle and bayonet every small cabin hidden away in the coves or by the sides of mountains streams. They had orders to seize and bring in as prisoners all occupants, however or wherever they might be found. Cherokee men—the young and the old, the strong and the weak— were seized in their fields, along the trails, on their doorsteps, beside their hearths. Indian women were jerked from their wheels, their looms, even from their beds. Children were seized at play. Families at dinner were startled by the sudden gleam of bayonets in the doorway and rose up to be driven with blows and oaths along the weary miles of trail that led to the stockades. A lawless rabble followed quick upon the heels of the soldiers. This rabble came so quickly that in many cases the Indians were barely on the march before their homes were blazing under the torch. Cattle were driven off, homes ransacked. By the end of May, 17,000 Cherokee had been herded into stockades across the Cherokee Nation. Meanwhile, some 4,000 of the imprisoned Cherokee began the long westward trek by boat and raft from Chattanooga down the Tennessee to the Ohio and thence to the Mississippi. Many lives were lost, and the Cherokee chieftains pleaded for permission to lead the remainder overland to the new home. And so the great migration began, the tragic exodus of a once proud nation. The route they took was north and west, running through a region where game still abounded, game they would need as food. There were men and women so old and gnarled they seemed more like mummies. There were newborn babies and unborn babies who chose just this moment to come into the world. There were the blind and the dying consumptives who had to be carried on litters. And there were idiots. As they picked up their few belongings they looked about, gazed toward the high peaks of the Great Smokies, toward the mountains that had sheltered them. Then they moved on, heads down. They were organized into detachments of a thousand each. There were more than six hundred wagons, five thousand horses, and a hundred or so oxen. The procession crossed to the north side of the Hiwassee at a ferry above Gunstocker Creek, then moved down along the river and northwest across Tennessee, through Athens, Pikesville, Mc- Minnville, Murfreesboro. The sick, the old, and the smaller children, with blankets, cooking pots and other belongings, rode the wagons and carts. The others trailed along on foot or on horseback. All the groups were routed through Nashville where contractors furnished them with supplies. They passed by the home of Andrew Jackson, the man who had betrayed them, but some of the Cherokee who had helped win the Battle of Horseshoe Bend for him stopped by to pay their respects to an old soldier. They were so beaten and sick at heart they did not even think of killing the man who had given the order for their removal. As the Cherokee plodded west the rains came and with them came cold weather. The roads, cut up by thousands of horses, cattle, and people, hundreds of wagons and carts, became an appalling morass through which travel was made with great difficulty and distress. There was death every day, and new sickness almost every mile. The venerable Chief White Path, who had been a great warrior, succumbed to sickness, infirmity, and hardships of the forced journey near Hopkinsville, Kentucky. He was buried near the Nashville road and a monument of wood painted to resemble marble was erected to his memory. A tall pole with a flag of white linen flying at the top was erected at his grave to note the spot for his countrymen who were following. The Cherokee crossed the Ohio at a ferry near the mouth of the Cumberland. The folks of Tennessee and Kentucky and Illinois saw them plodding along, heads down, sickness in their hearts and souls. A traveler from Maine encountered a party led by the Rev. Jesse Bushyhead. What he saw was reproduced several weeks later in the New York Observer. "On Tuesday evening," he reported, "we fell in with a detactment of the poor Cherokee Indians . . . about eleven hundred of them— sixty wagons, six hundred horses, and perhaps forty pairs of oxen We found them in the forest camped for the night by the s'.de of the road . . . under a severe fall of rain, accompanied by heavy wind. With their canvas for a shield from the inclemency of the weather, and the cold wet ground for a resting place, after the fatigue of the day, they spent the night. . . . "We learned from the inhabitants on the road where the Indians passed that they buried fourteen or fifteen at every stopping place, and they made a journey of ten miles per day only on the average. . . . "When I read in the President's Message that he was happy to inform the Senate that the Cherokee were peaceably and without reluctance removed—and remember that it was on the third day of December when not one of the detachments had reached their destination; and that a large majority had not made even half their journey when he made the declaration, I thought I wished the President could have been there that very day in Kentucky with myself, and have seen the comfort and willingness with which the Cherokee were making their journey." The Cherokee moved through Southern Illinois, past Golconda, Vienna, Anna and Ware, until they reached the Mississippi River opposite Cape Girardeau, Missouri. It was hard, fast winter now. And their crossing was delayed by the passing ice which endangered the boats that were to ferry them. For days they were compelled to remain beside the frozen river. Hundreds were sick or dying, penned up in the wagons or stretched out upon the ground. They only had a blanket overhead to keep out the January blast. The crossing at last was made in two divisions. One was effected at Cape Girardeau. The other made at Green's Ferry, a short distance below. Safely on the other side, the homeless trudged on. They crossed Missouri, past Farmington, Rolla, Lebanon, Springfield, Monett. through a corner of Arkansas and entered Indian Territory, a confused, disillusioned people who only had a great expanse of country upon which to lay their tired and weary bodies. It was strange and unfamiliar country. The mountains of home were a thousand miles and forever away. The Cherokee had come to the end of their trail into exile in March, 1839. The journey had taken six months and in the hardest part of the year. More than 4,000 had died along the trail, to be buried in unmarked graves in strange and alien soil. Thirty-four

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

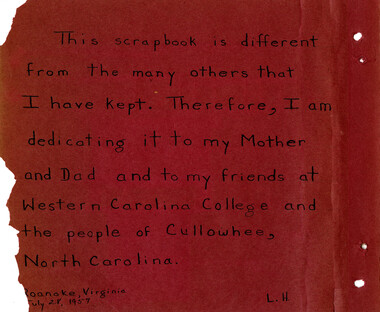

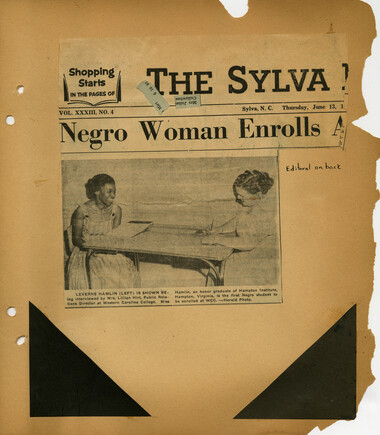

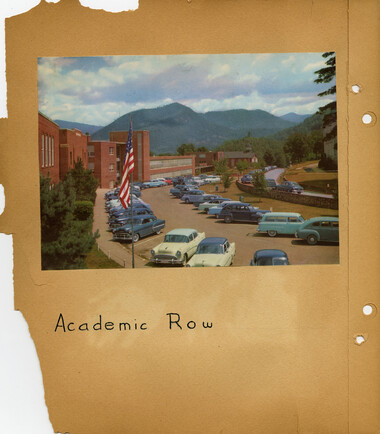

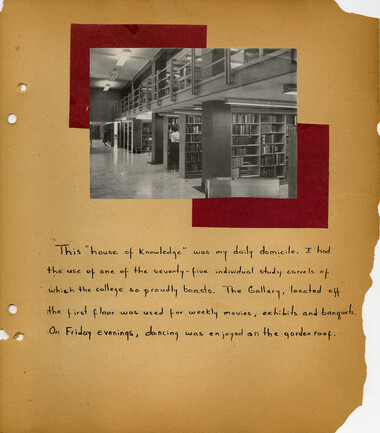

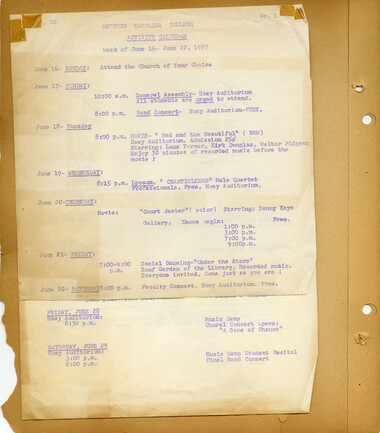

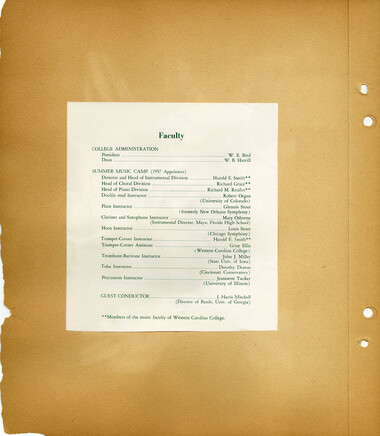

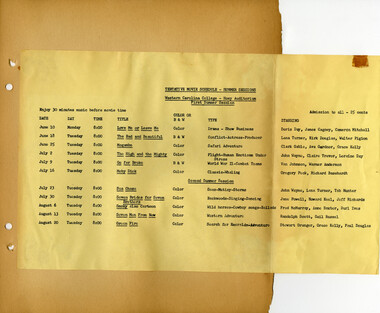

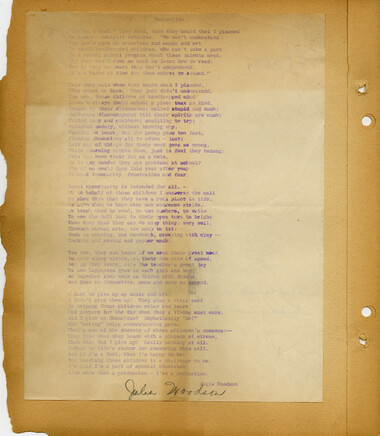

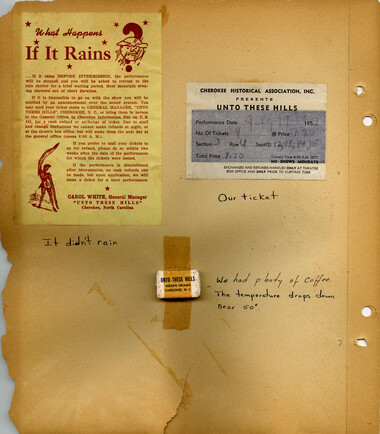

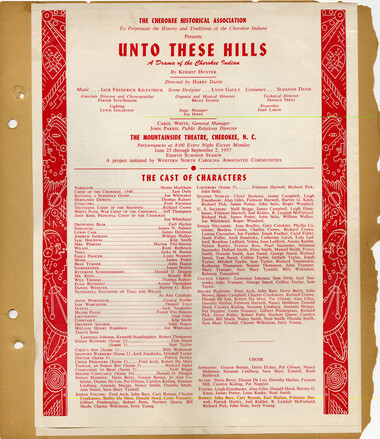

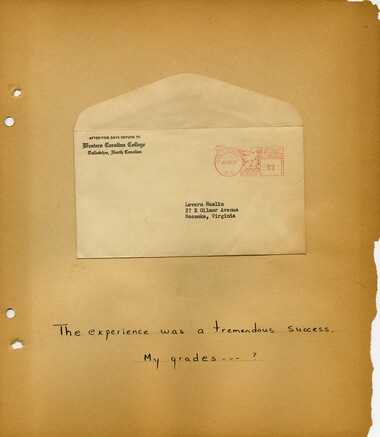

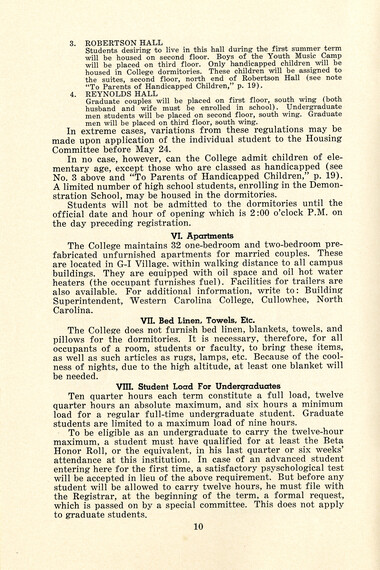

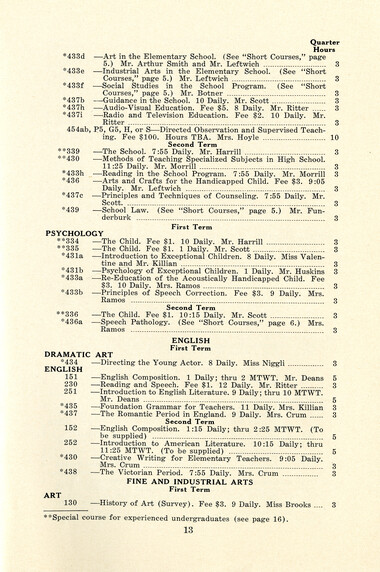

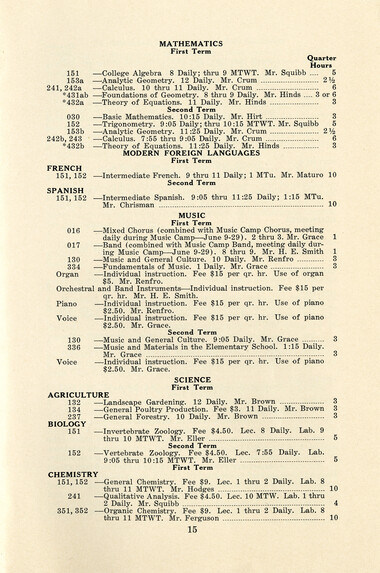

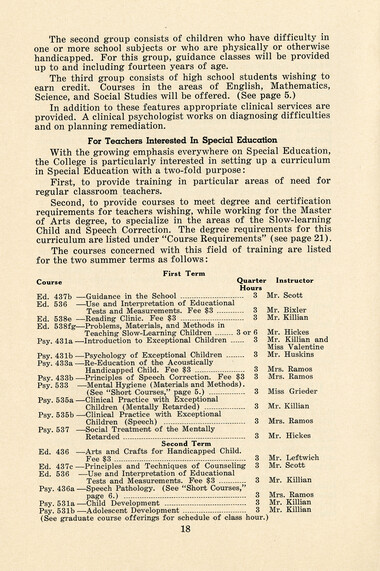

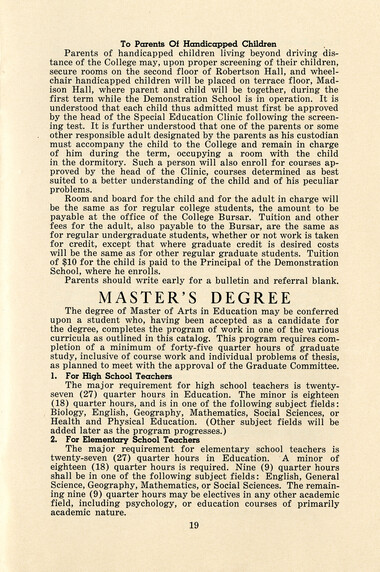

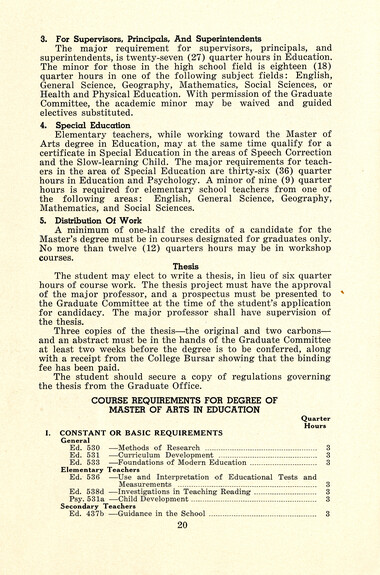

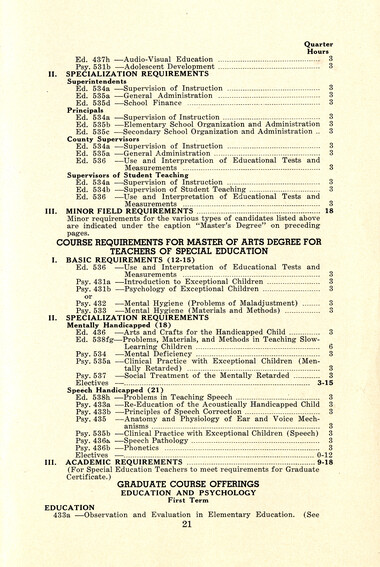

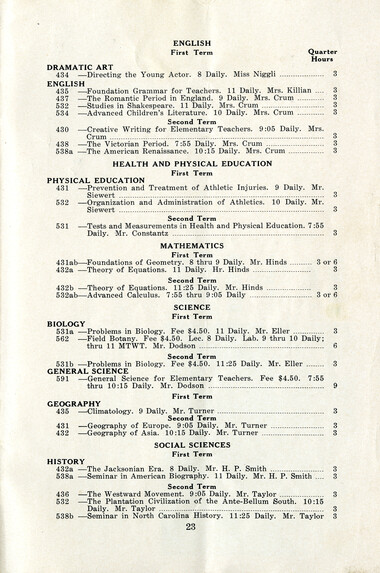

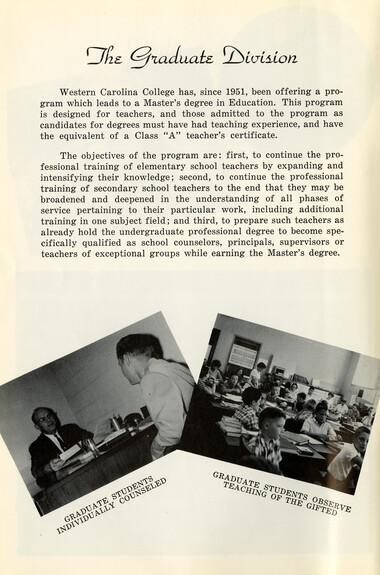

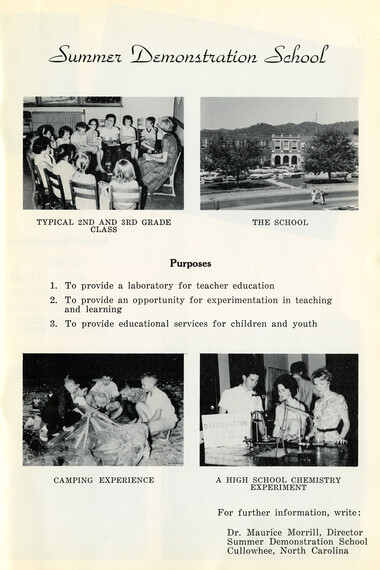

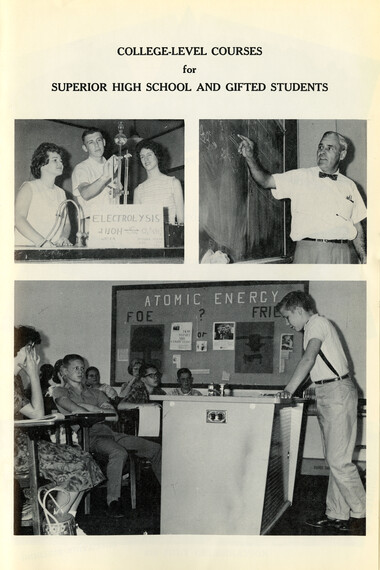

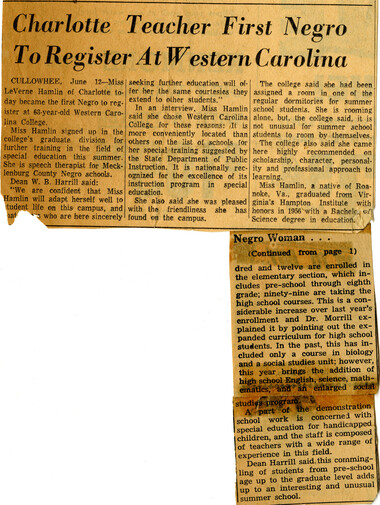

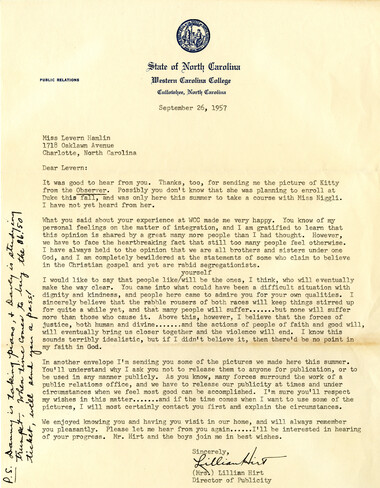

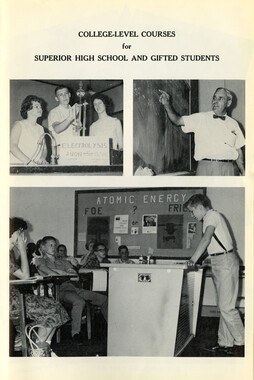

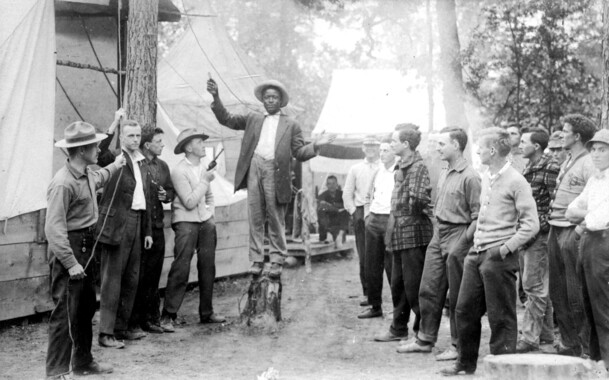

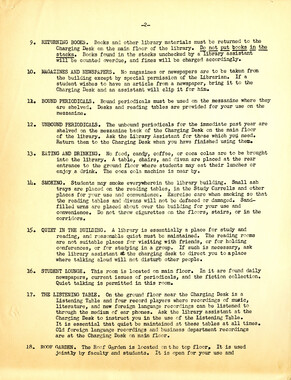

This 42-page scrapbook was put together by Levern Hamlin, a Roanoke, Virginia native who moved to Cullowhee, North Carolina in 1957 to attend Western Carolina College. Levern Hamlin was not only the first African American to attend Western Carolina College but the first African American admitted to a North Carolina state college. As a speech therapist practicing in Charlotte, North Carolina, Hamlin decided to further her training in special education through the college’s graduate division. The scrapbook begins with Hamlin’s account of her arrival at WCC on June 11, 1957 and includes numerous clippings describing the significance of her enrollment. The scrapbook contains entries from her summer semester at WCC extending to July 20th, 1957 when she arrived back at her home in Virginia. Hamlin had previously attained a Bachelor of Science degree in education from Virginia’s Hampton Institute in 1956. Also included are pamphlets and clippings at the end of the scrapbook.

-