Western Carolina University (21)

View all

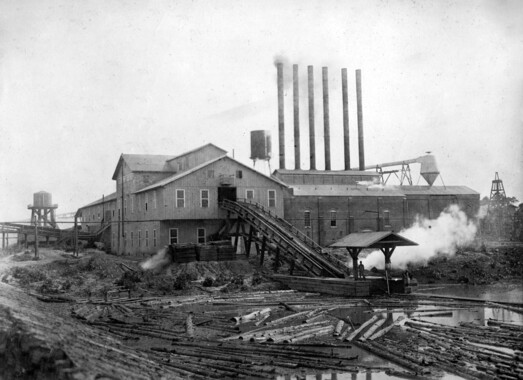

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- George Masa Collection (135)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2901)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (422)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6798)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (153)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1463)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (2008)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2924)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1941)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (195)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1672)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (556)

- Graham County (N.C.) (236)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (525)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3569)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4913)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (35)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (13)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (215)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (135)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (982)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2182)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (86)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (3)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (185)

- Envelopes (73)

- Exhibitions (events) (1)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (815)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (6090)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Notebooks (8)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12976)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (5)

- Portraits (4568)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (181)

- Publications (documents) (2443)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Relief Prints (26)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (1)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (18)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (462)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1482)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1923)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (190)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (111)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (2012)

- Dams (107)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1196)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (45)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (119)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (72)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

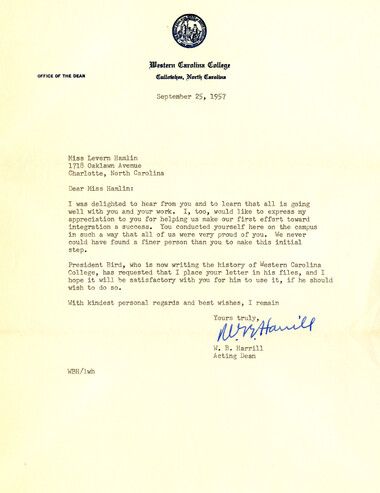

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

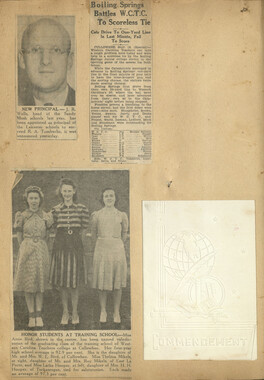

Levern Hamlin scrapbook

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

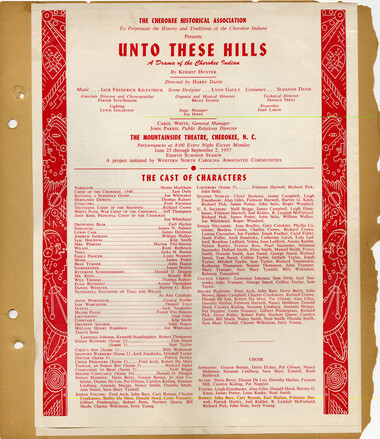

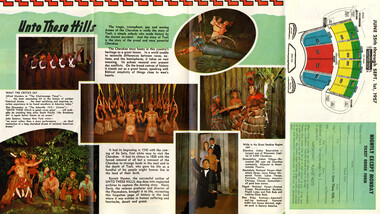

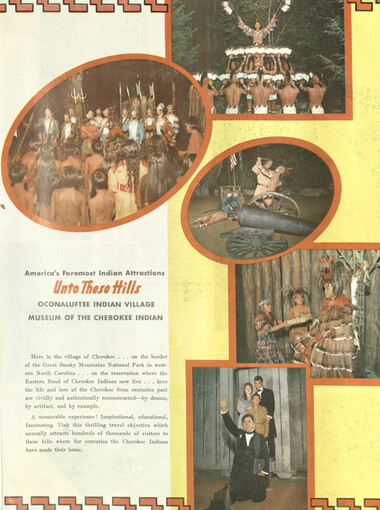

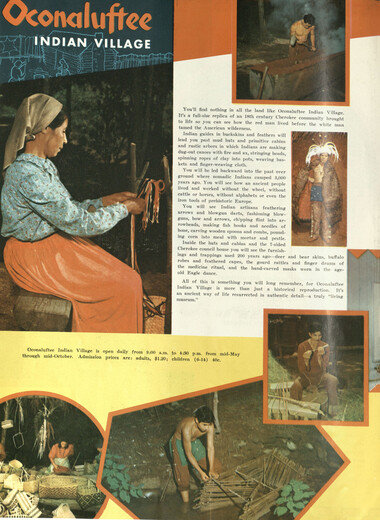

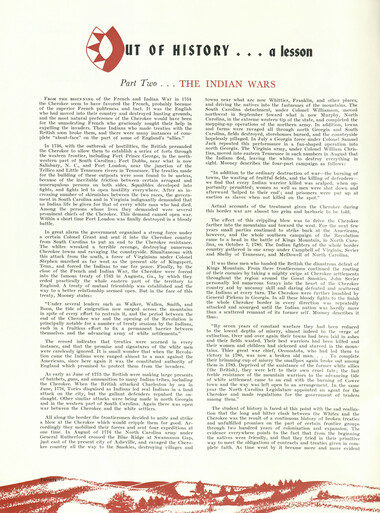

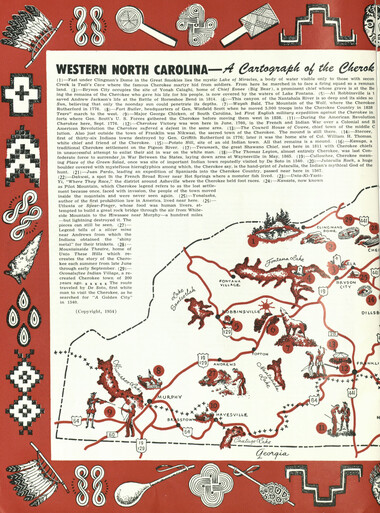

UT OF HISTORY ♦ ♦ ♦ a lesson that the westward tide of expansion was not concerned with treaties and pledges, that border settlers outside the actual domain of civil government along the coasts made their own laws and pursued their own course. In primitive defense of their homeland the Indians fought back, finally embittered and angered to the point of open war in reckless and foolhardy abandon. Thus the long history of struggle and hatred had its basic roots in a selfish and overriding desire for gain on the part of a few, and in the stubborn refusal of certain classes to deal honestly and fairly with these primitive people whose sole desire was to keep their homes in peace. But with the close of the wars in 1783 a new era was about to begin. Part Three . . .THE REMOVAL TO THE WEST A great change seems to have come over the remnant of the Cherokee nation during the twenty-five or thirty years following the Revolution. Although a few influential leaders had taken up the cause of American Independence, the vast majority of the nation had fought against the Americans as being the people who were encroaching upon their lands in the Alleghanies. By the end of the Revolution the Cherokee had lost their hunting grounds in West Virginia and Virginia. They had been driven out of South Carolina. Their lands, once embracing nearly 50,000 square miles, has been reduced to a few hundred miles of north mountainous western corner of North Carolina, a portion of north Georgia, and a small eastern corner of Tennessee, and even then there were no actual boundaries. A new generation had grown up from the scattered survivors of the war. Daily contact with white settlers along the borders had served to give them some knowledge of the ways and attitudes of the white man. Missionaries had penetrated their country and had succeeded in spreading a doctrine of peace and brotherhood, establishing churches, setting up a few schools. Gradually the old order had changed, and a new view had emerged. Under a wiser group of leaders the Cherokee began to find that peace, even at the price of gradually losing all they had, was perhaps better than open war and the eventual loss of everything by force—a bitter and desperate choice. Many of the old generation were gradually drifting westward. The years following the Revolution showed a continuous stream of wanderers moving toward the Mississippi and beyond, where settlements were carved out of the wilderness. Never instinctively a warring nation except in self-defense, the Cherokee had begun to realize that their course for the past hundred years not only had been fruitless as far as physical gain was concerned but also had shaken and confused their thinking to such an intent that they had greater difficulty than ever adjusting to the changing life and times. They were turning again to agriculture, to the development of fields and farms. From the white men they learned farming methods vastly superior to the primitive system of their ancestors. They began to cultivate the valleys of north Georgia and eastern Tennessee into small farms, and in North Carolina they planted steep sides of the Great Smokies. At this point the Cherokee were again ripe for a new era. One wonders what would have happened if by some means the whites could have learned to accept them as useful citizens, if the Cherokee bad been able to make clear their desires to become a part of the confusing new trend of life on the American continent. But the seeds of hate, planted for 200 years in all parts of the country, had grown into a harvest of weeds which could not be conquered. Shortly after 1810 the great Cherokee genius, Sequoyah, produced one of the most remarkable inventions of modern times— a Cherokee alphabet. It was a strange mixture of symbols representing the various sounds of the language, the only written language of any American Indian tribe. The new system spread quickly through the nation, and within a few months all the Cherokee were able to read and write in their own language. By 1827 the Cherokee council voted to establish a newspaper. As Mooney reports, "Early the next year the press and types arrived in New Echota (Ga.) and the first number of the Cherokee Phoenix, printed in both languages appeared on February 21, 1828. The first printers were two white men, Isaac N. Harris and John F. Wheeler, with John Candy, a half-breed apprentice. Elias Boudinot, an educated Cherokee, was the editor, and Reverend S. A. Worcester was the guiding spirit who brought order out of chaos and set the work in motion." In the early 1800's the Chreokee perfected their national government for the first time, modeling it after the American Constitution, and replete with a democratic system of procedure. And as final proof that the Cherokee had at last abondoned the old way of war, they flatly refused to listen when Tecumseh visited the southern nations in 1811 and tried to organize a vast Indian union from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico and fight the white man. The die had been cast on the side of peace, and one cannot but feel that here, at this strategic point in American history, the whole course of the future settlement of the west might have been different if enough farsighted men had studied the altered charter and the sincere efforts of the Cherokee. When the British struck again in 1812, the Cherokee had vowed to have no part whatever. But when they found that their traditional enemies, the Creeks, had sided with British and were causing disruption in the south, they quickly sent a whole regiment of volunteers to join Andrew Jackson and repel the enemy at the famous Battle of Horseshoe Bend, Ala., in 1814, where Junaluska personally saved the life of General Jackson. Again the stage was ripe for peace and for the reception of the peaceful Cherokee into the American scheme. It is within this portion of the Cherokee history that the drama at the Mountainside Theatre is concerned, the desparte efforts of the remaining 20,000 of the Cherokee nation to keep their homes in the mountains and become a part of the American government. Meanwhile numerous treaties and purchases were arranged during the years between 1810 and 1835, and always the Cherokee were squeezed farther and farther into the hills, away from the rich fields and fertile valleys, and as always they were met with broken promises and treachery. Only Christian patience, and the courageous determination of men like Junaluska and John Ross held the people in check. The discovery of gold in Georgia in 1828, with its great flood of land-grabbers, made conditions even more intolerable. A long series of parleys began in Washington as Cherokee sympathizers tried desparately to plead their cause, and throughout all this the Indians retained an amazing degree of patience and humility. Finally, in 1835, a handful of malcontents were flattered into signing a treaty which ceded the entire Cherokee country to the federal government for less than fifty cents an acre in return for lands in Oklahoma. The Cherokee Nation was stunned when Congress actually ratified the ridiculous treaty and for three more years they argued frantically, aided by such men as Daniel Webster, John C. Calhoun, Henry Clay, Stephen Wise, Sam Houston, and a host of other leaders in every walk of life, but to no avail. The shifting political scene of the 1830's made almost a joke of the cry of the Cherokee. In 1«38 General Winfield Scott was ordered to move the Chreokee to the west. Th story of that mass exodus, one of the most dismal pages in American history and one little known, is enough to startle and shame the modern reader. These people, now highly civilized and intelligent, an honest and since part of the life of this region, publishing their own newspaper, conducting their own schools, and according to actual records the most law-abiding and peaceful residents of the whole mountain area, were herded into stockades for weeks, then marched overland nearly a thousand miles, almost completely despoiled of property, homes, and possessions. "*»*!!$

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

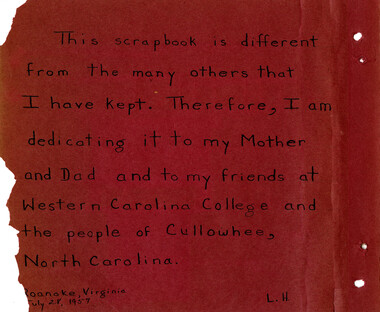

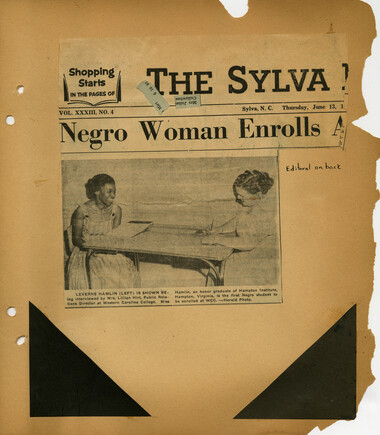

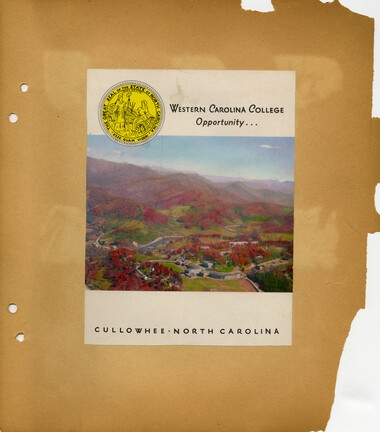

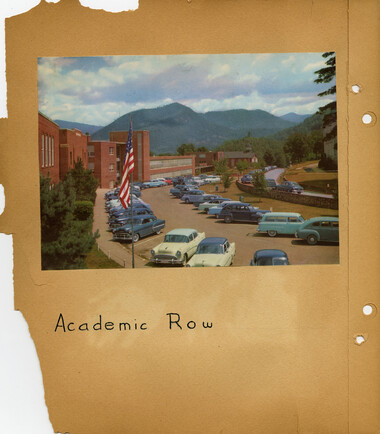

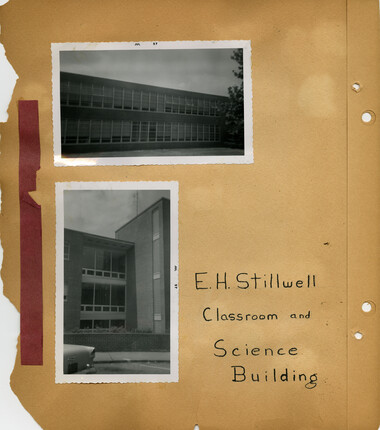

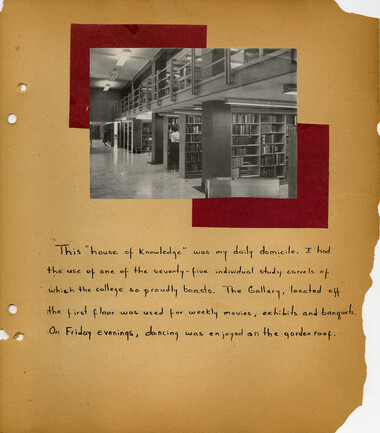

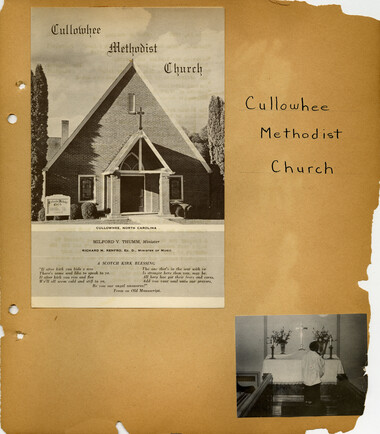

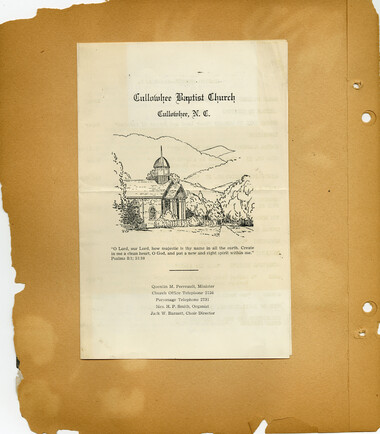

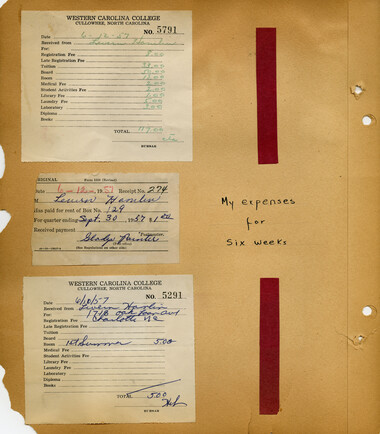

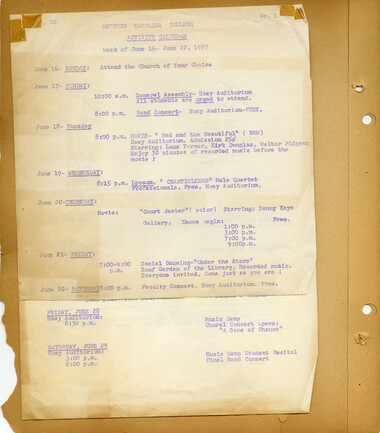

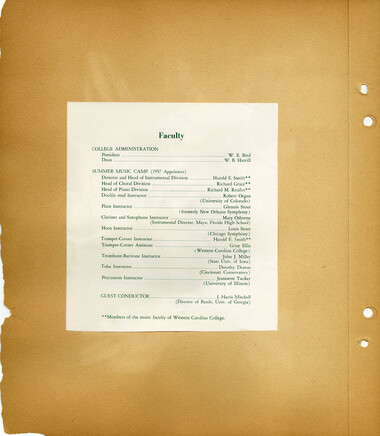

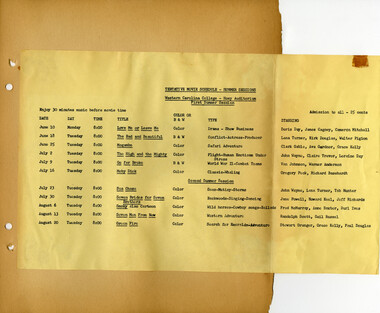

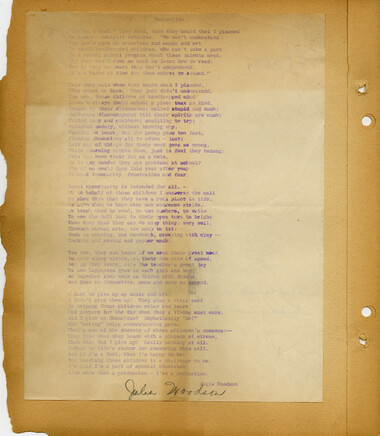

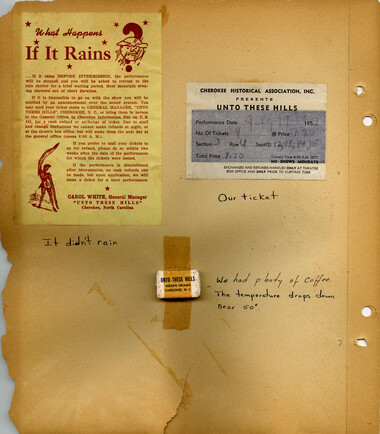

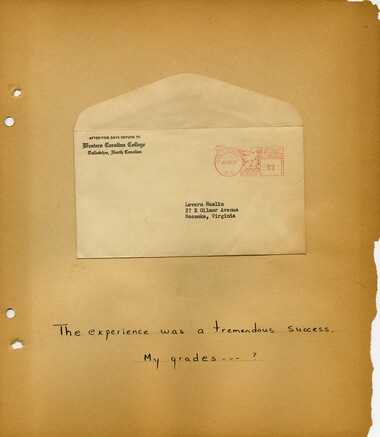

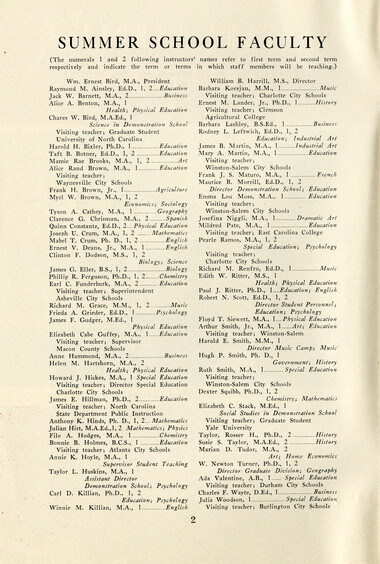

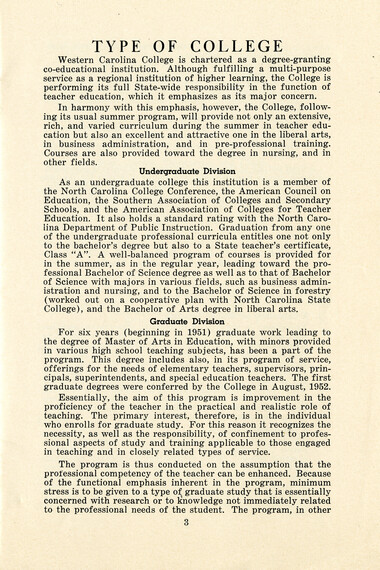

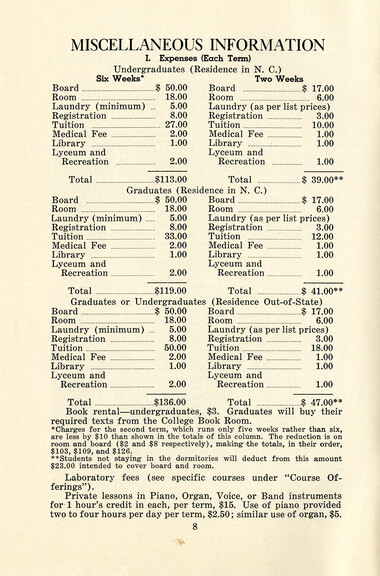

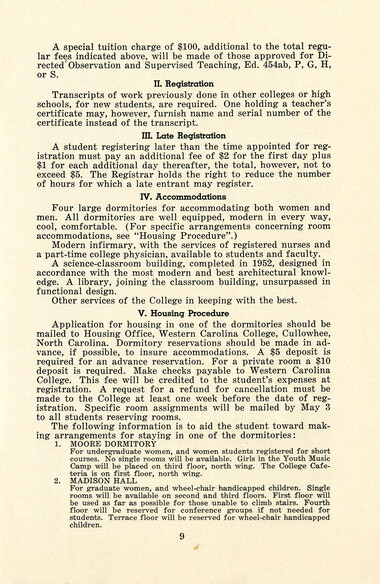

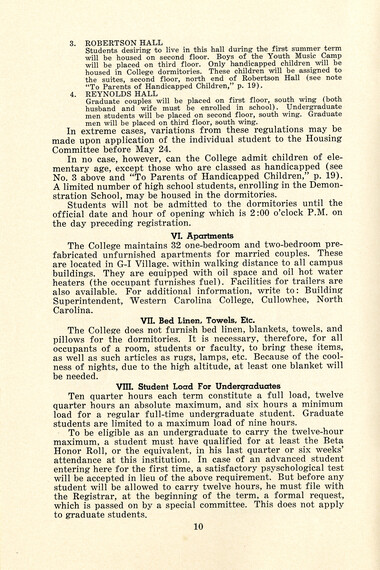

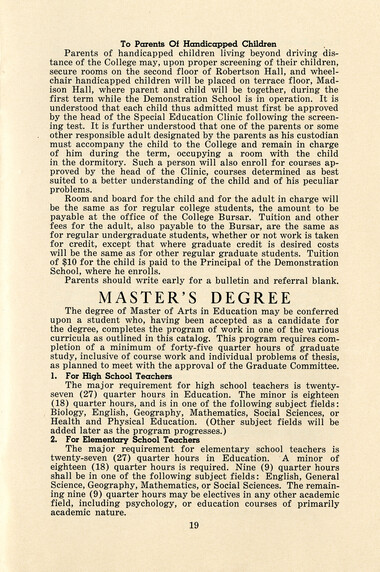

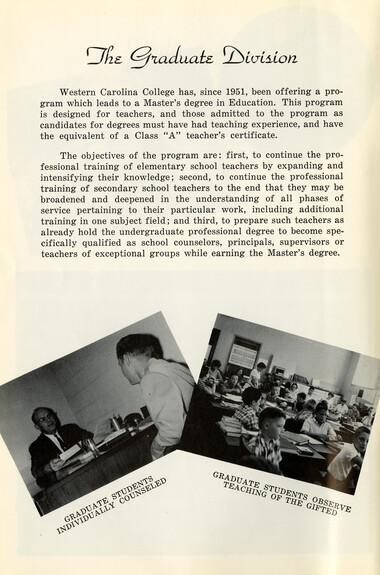

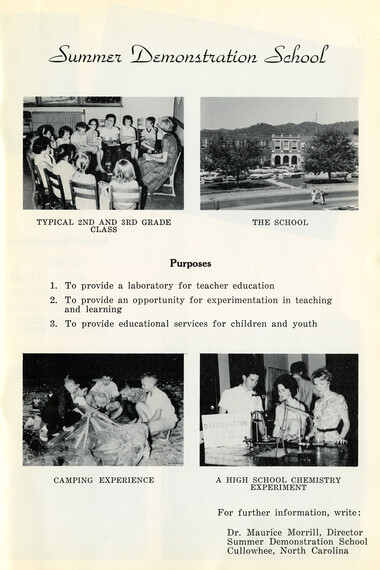

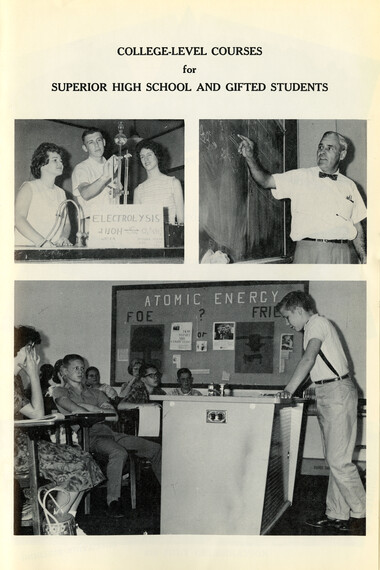

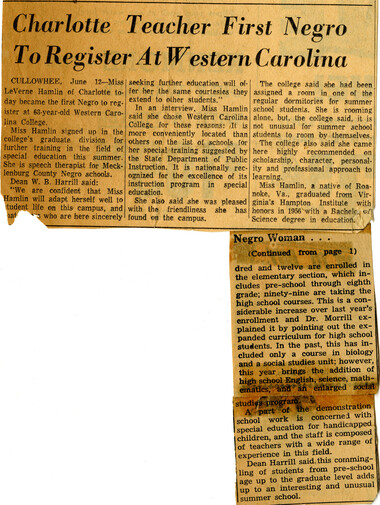

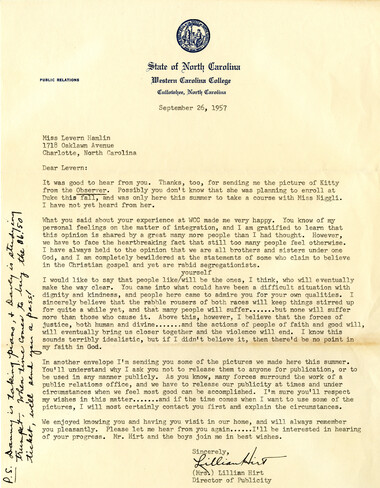

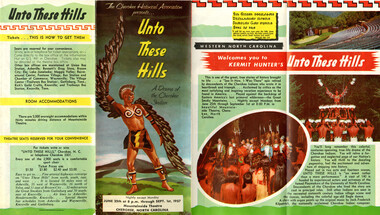

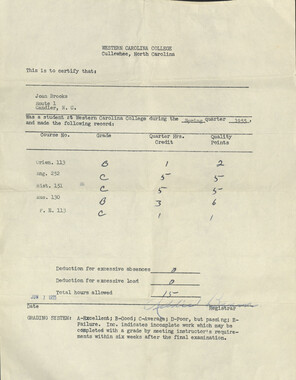

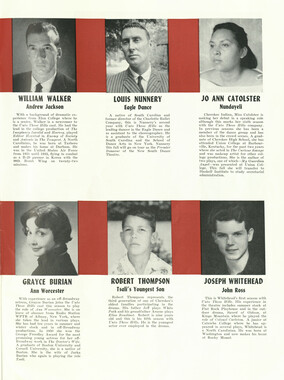

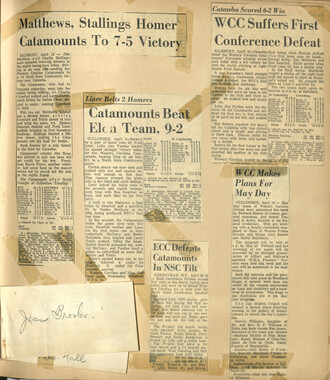

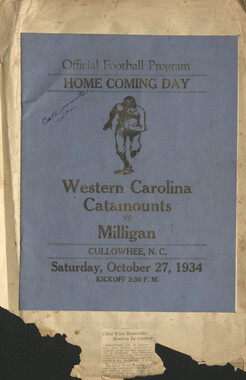

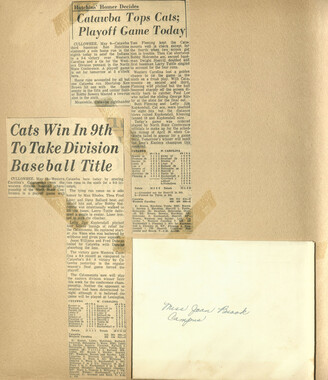

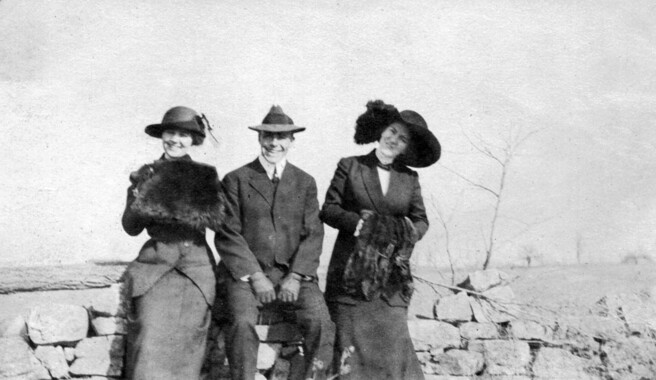

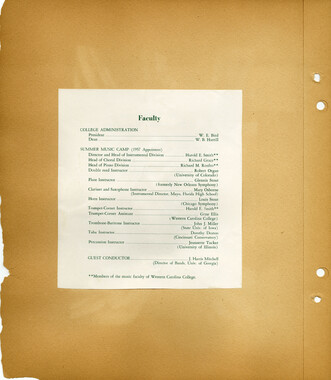

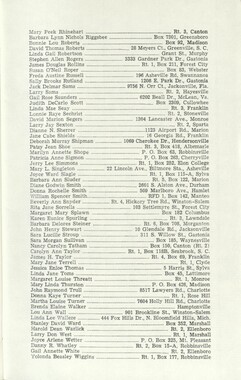

This 42-page scrapbook was put together by Levern Hamlin, a Roanoke, Virginia native who moved to Cullowhee, North Carolina in 1957 to attend Western Carolina College. Levern Hamlin was not only the first African American to attend Western Carolina College but the first African American admitted to a North Carolina state college. As a speech therapist practicing in Charlotte, North Carolina, Hamlin decided to further her training in special education through the college’s graduate division. The scrapbook begins with Hamlin’s account of her arrival at WCC on June 11, 1957 and includes numerous clippings describing the significance of her enrollment. The scrapbook contains entries from her summer semester at WCC extending to July 20th, 1957 when she arrived back at her home in Virginia. Hamlin had previously attained a Bachelor of Science degree in education from Virginia’s Hampton Institute in 1956. Also included are pamphlets and clippings at the end of the scrapbook.

-