Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (24)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1388)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (1794)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2393)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1886)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (161)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1664)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (233)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (478)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3522)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4692)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (25)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (12)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (211)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (981)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2113)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (247)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (68)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (184)

- Envelopes (73)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (811)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (619)

- Maps (documents) (159)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (5835)

- Newsletters (1285)

- Newspapers (2)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (12975)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (5)

- Portraits (1663)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (151)

- Publications (documents) (2237)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (1)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (15)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Vitreographs (129)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (282)

- Cataloochee History Project (65)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1407)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1744)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (167)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (110)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (1830)

- Dams (103)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (61)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (917)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (154)

- Hunting (38)

- Landscape photography (10)

- Logging (103)

- Maps (84)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (71)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (245)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

Interview with William Ritter

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

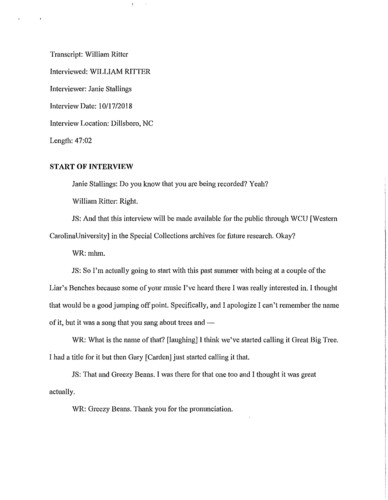

Transcript: William Ritter Interviewed: WILLIAM RITTER Interviewer: Janie Stallings Interview Date: 10/17/2018 Interview Location: Dillsboro, NC Length: 47:02 START OF INTERVIEW Janie Stallings: Do you know that you are being recorded? Yeah? William Ritter: Right. JS: And that this interview will be made available for the public tlu·ough WCU [Western CarolinaUniversity] in the Special Collections archives for future research. Okay? WR: mhm. JS: So I'm actually going to start with this past summer with being at a couple of the Liar's Benches because some of your music I've heard there I was really interested in. I thought that would be a good jumping off point. Specifically, and I apologize I can't remember the name of it, but it was a song that you sang about trees and - WR: What is the name of that? [laughing] I think we've started calling it Great Big Tree. I had a title for it but then Gary [Carden] just started calling it that. JS: That and Greezy Beans. I was there for that one too and I thought it was great actually. WR: Greezy Beans. Thank you for the pronunciation. William Ritter 2 JS: Yeah, you're welcome. I wrote it down and was like "I got to make sure I pronounce it right." Can you tell me about those songs a little bit. Why you decided to write them. What they mean to you, that kind of thing. WR: So the first one. The one. The Great Big Tree One. I actually wrote for Gray Carden's play Outlander, which is about Kephart and he's a really interesting character that had a really important role, maybe the most important role, in getting the Great Smoky Mountain National Park founded. And he wrote, very famously, about mountain people. But anyways, Gary wrote a play about him and I was involved in the first production of it just as a musician. I chad a few bid parts and that was in Parkway Playhouse in Burnsville. But then in another production in Asheville, in it was a reader's theatre I think they call it. Basically, instead of doing a whole big production with a lot of rehearsals everyone needs to memorize blah, blah, blah. It's just very stripped down. People hold the scripts and they do a couple of rehearsals and then they just go do it. And I was asked ifl would do the music, Gary obviously must have requested that I would be the person who did the music, so I did a lot of music in between the different scenes, and they use a lot of traditional stuff for most of that but one part I basically wrote a tune. The director had basically opened it up, said "If you want to write anything, that would be great. We can do some traditional stuff." So that one just kind of came to me and it's in a part in the play where Horace Kephart is talking about how the lumber barons had essentially come through southern Appalachia. One of the most famous Lumber baron was named William Ritter. Not related, but came through and forested the mountains here. It's amazing how much they've recovered in someways, but they were pretty much stripped down, totally denoted. So that's about. .. Gary appreciated it partly because there's lines in there about. .. It's not necessarily that the mountain people were happy to William Ritter 3 have to do that. There's a line about it. It's just kind of bitter sweet, a lot about that tree's been there since since that person's grandfather's time but they had to basically cut it down because they couldn't afford their taxes otherwise or basically financial reasons they had to do something they didn't really want to do. But anyways, so that's how that song came about. Greezy Beans was kind of a separate thing. I don't even remember when I wrote it. It's just kind of a funny song. Oh no, I remember exactly! I was asked to perform at a seed library opening in Boone, at the library. It was really clever, they took the old card catalogues like the libraries used to have and they just, cause a lot oflibraries have those laying around cause it's all digital now, they don't need those. They took and they made it so you could put seed packets in them and come check out seeds to plant in the garden and bring back. It's really cool. Anyways, they asked me to come perform a song for the opening, my friend Dave Walker in Boone. And then the day came around and I had no song. I was going to just sing something like "Inch By Inch, Row By Row" an old Pete Seeger song but I never learned it and I was like, "I don't know what I'm going to do." I was driving on my way to Boone from Winston-Salem and Greezy Beans came to me and I wrote it down on a sheet of paper while keeping my eyes on the road. [mimicked driving] And when I got there I performed it. I probably wrote it in about thirty minutes. JS: I remember that evening, everybody seemed to love that song. WR: Oh yeah, when I sang it at Liar's Bench. I performed it some partly because a big part of what I do is seed saving. That's one of my main big things. I have a freezer that has a couple hundred different seeds. Mostly southern Appalachian traditional seeds that people have passed down from family not things that I got from a catalog. Stuff that you really have to get passed to you. Some people call them pass along seeds versus the term heirloom. I don't like the William Ritter 4 term heirloom because if your grandmother gives you a loom that's been in your family: that's an heirloom. If you take it to the antique shop and you sell it: that is not an heirloom. So when selling these "heirloom" seeds like in a catalog or on the internet, not saying that's not great, I'm glad that they're keeping them in circulation and from going extinct. But on the other hand, there's something in between the person who has the seeds and the ones that get them traditionally wouldn't have been there. I think it's really important when you can be like, "oh yeah, I got that from my neighbor" or "yeah, I got that from my friend such-and-such." Or even, "yeah, I got this from this old man that I met at the farmer's market." It's a completely different thing to me than "yeah, well that looked cool. There's a cool picture on the internet and the seeds come from traditionally grown in Maine and I now grow them in North Carolina." It's just not the same. So anyways, I wrote that song and instigated that a little bit. Mostly just about Greezy Beans which are a famous Appalachian bean. The thing that makes them Greezy is that they are shiny; the pods are very shiny so it looks like they have grease on them. So I like to sing that song as a part of my seed saving program. I know of got into seed saving through music originally. Music was every much something that I didn't grow up with music in my family. It's not like I inherited some kind of awesome fiddle tradition. I wish! I grew up in Mitchell County, it's very rural county in Western North Carolina and my parents were actually artists and they were both from up north. Damn Yankees is the term for people who move and stay. I didn't think much of it when I was growing up. I was pretty ready to not be in the mountains. In a lot of ways I think I was kind of ready to get out. But by the time I was in the late stages of high school I really liked being in the mountains. I started to really identify as a mountain person even though I hadn't when I was younger. I was more begrudgingly; I felt like I should go live in an urban William Ritter 5 place somewhere and then by the time I came down here to go to school I realized. I became very homesick and the music kind of connects to a culture that I was somewhat a part of. As much as I could be without having been part of the kinship network in terms of my blood relations. I was related to anyone there but. I grew up there so I was from there and I'm not from anywhere else. I might not have the same accent necessarily or anything but as I started into undergrad here I really got homesick like I said. That's where I start this whole Odyssey of really learning old time fiddle, old time music, and I eventually started meeting a lot of old time musicians, old timers and leaming from them directly. That became this really special, rich thing that in many ways is more important than the music I loved itself. The cmmection with people was this really rich thing and so later on when I wanted to start a garden I wanted to get some seeds. But I was like, "I'm not going to get these from a catalog! I'm going to find somebody!" Like I had with music that knows this music that knows this music and I'm going to learn it that way, learn it from them and be cormected to this whole history ands this people in a really grounded way and then a few later I had a hundreds of seeds. JS: What instruments do you play? I know you play guitar. WR: My primary instrument is fiddle. Fiddle, but I joking say I play string-ed things. Fiddle, guitar, and banjo, mandolin. I can fake other stringed instruments cause in some ways they're all kind of similar, but all the kind of classic music instruments. Well, I can play a dulcimer. Anyone can play a dulcimer. Basically those. JS: Do you see music, you work in music, as work itself? WR: I think I should be paid for it. [laughter] It certainly feels like work when I'm not enjoying it which happens sometimes. It's weird, I think the primary motivator, I love the music William Ritter 6 so it's not really hard to get me to share it. If anything it's not monetary reasons that stop me from sharing. Often times it's ifi don't feel it'll be appreciated I'm very hesitant to share it. It's some thing that is so dear to me it really it's like a core part of who I feel like I am as a person and something I just cherish. I just don't want to do it in front of people who just won't understand it. I'm happy to maybe help them get it, do things that maybe- The joke with old time music is, "Old time music: better than it sounds." [laughter] So you kind of have to help people, work with them if it's their first experience they just like, "that just sounds kind of bad." But if you give the whole historical context around it and kind of community context and can help them understand what they are listening to it really enriches their experience. In terms of "do I feel like it's work?" That really depends on what I'm doing and how much I'm enjoying it. I do tend to want to be paid primarily because I feel like there's a lot of people that for them that is their primary income. They're literally trying to make a job out of playing music and ifi go around places and play for free I am undermining them. It drives me crazy. When people that are retired or have a pretty uncomfortable revenue sti·eam play for free. It's like, "oh, I just love doing it." Well, you're setting a precedent for someone that's actually trying to do this full time. You're really undermining them by being like, "I'll play for free." I'm not saying have to charge a lot of money but you should receive something. It's really messed up that there's certain, particularly art forms, that people have worked on to be good at and might have spent years of their life if you counted their practice hours, or their working in hours, and for any other skill you'd be compensated for that. It's really messed up that you wouldn't be. If you're a plumber and you have ten years experience plumbing you should get paid pretty well. You would expect to be compensated and no one would be surprised. It's like the old saying, "oh, well, I can't give you anything but it would be great exposure." People die of exposure all the time. William Ritter 7 It was a diner or Innovation that was like, "yeah, you can come play for free." Which I would maybe do if it was a jam. I would want beer, at least except being paid beer. There's an expectation that you would just come do it for free. So I want to say, "okay, well hey, Innovation," as an example. They pay their people that come play for them, I just want to say that. If they wanted me to play for free. In my mind I might be like, "oh okay. Well I'm having a party and you should come to my house and give away free beer, and it'll be great exposure. I can't pay you, but it'll be great exposure." That's kind of what it's like to ask someone to play for free. Whether I necessarily conceive of it as work, per say, is yes and no. But I do think I should be paid for whatever this is that I'm doing. JS: How you do view it [performing music] in you're life? I feel like we've already gotten to this a little bit. WR: How do I view it as part of my life? I definitely feel like it's so much a part of my identity. Iflet's say, for example, I lost like a bunch of fingers in a horrific accident and wouldn't really be able to play. I would figure out a way to play, somehow. That would be really hard for me. I would feel like a part of my identity was taken from me. JS: Where do you draw inspiration for what you write, what you play? WR: You know, some people can probably that question a lot more directly, maybe they're more conscious in what they know, what they're pulling from. It's a really organic process for me. When I sit down to write a song I feel the inspiration come on. It's has something with ADD I'm pretty sure. It's like when you get in those hyper focused modes and you have this [hand gesturing], "I can relate to this," eureka kind of thing. You get all this energy and go forward sometimes it falls flat on its face and you crumble it up and you throw it in the trash. But other times you've got something and of course that's all influence though I'm not William Ritter 8 thinking of it at the time. I'm not saying, "oh well, this music is really inspired by"- I don't write a song that's Hank Williams-esque. I don't necessarily do that. It's more since I listen to just to old time music and then when I try to listen to modern music I listen to stuff from the fifties. Or Gilliam Welch or someone like that. Some slightly more contemporary musicians: Tim O'Brien is actually probably my favorite musician. All that stuff definitely, just from me ingesting it so much, has-just like if you're eating potatoes all of the time a percentage of you're proteins are potatoes. It's the same way with all of the music, I've ingested so much of a certain genre so when I write music it's very much in within those geme frameworks in terms of techniques; things that I use, but I'm not super conscious of where I draw from. JS: When people hear your music what do you think that they think? What do you want them to take away from it? WR: Well, I do want them to enjoy it. If it's a funny song I definitely want them to laugh, but on the subtext, I want them to have a deeper understanding of mountain culture. I want you to think about something that you didn't think about before or didn't know about before. Maybe you just didn't about Greezy beans and that made you. You have this song that's educated you about Greezy beans in a fmmy way. That's something that I, definitely a subtext that I feel somewhat kind of like an ambassador for Appalachian culture whether I have the right to be or not. I always try to not necessarily shed a positive light, but just to make people have a deeper understanding. Help them have a more critical understanding. For example, this railroad, all of the places that it moves through like a big section ofrock where they blasted away a section of the mountain. That was done almost assuredly by slave labor. Slave labor well after the emancipation, so that would mostly be chain gang work and to be a black person in the 1870s you'd get on a chain gang for literally doing nothing. Just for making eye contact, for example, William Ritter 9 to someone you shouldn't make eye contact with could get you on a chain gang, breaking up rocks. That very famous, it's not necessarily famous anymore, there was a great tragedy just down the river right there at the Cowee tunnel where nineteen, actually more than that. Basically a bunch of convicts were chained together, they were one a raft, and they were moving the raft off the river. There wasn't a trestle yet and they were building the Co wee tunnel and it was Christmas Day, I think maybe 1901, and they, for whatever reason, some said that there was some water and ice on the boat and they were kind of uncomfortable about it clearly cause ice water on you're feet is terrible. They were probably barefooted and, for whatever reason, the raft capsized and you imagine going into a freezing cold river chained together with other people. They probably can't swim, even if you could swim it probably wouldn't help you very much. I think the water was supposed to be higher than the snow. Anyways, nineteen men died that day. It made the news because nineteen men died, but men died all down this railroad if they got so Sarcoidosis, or if they tried to run away, or if they just- They buried them there on the side of the railroad and there's this whole old history. That's something that's a really dark history, built I feel like it's important that when people come into the Appalachian landscape that they know things like that. That they should have a deeper understanding of what's around them. I'm definitely not trying to, I want to shed a lot of positive light, but I think I mostly want to help people have a more complex understanding of what's around them when they come here. For some probably people that's probably more than they want to know, "that's really sad. I came here to have a drink and enjoy music." [laughter] JS: Sorry, I'm trying to figure out the best way to ask a couple things. Do you see a difference in performing for people who are also from this area versus- WR: I know where you're going William Ritter 10 JS: What are your thoughts on that? WR: So, on a slightly sidetrack from that, in someways I guess it's similar to talking to people. Let's say in this experience right here I'll have a different kind of coded language than I would ifi was down in Bryson farms supply right here, talking to Kevin and Armando and everybody down there. I would probably have a much thicker accent come on. Sometimes that's intentional of me and I hate that. A lot of times it's not and Sarah, my wife, will make a lot of fim at me when I get on the phone and with some old timer fi'iends of mine and she grins and "hahaha." There's definitely code switching and that happens with music too. When I perform, with a real mountain crowd I'll play a lot more bluegrass. I'll pull out some stuffi think might really resonate with, but if I was in more of a Floridian type of crowd I might do a different set of music. I might talk a little more about the history. I might try to do a little more Appalachian, not evangelism in terms of a religious sense, but in terms of trying to deepen their understanding of the region as a place where they should get to know people and not live in gated communities. [laughter] Then sometimes there's a tension when I'm in a place where I feels like there's both and I think sometimes I'm trying to figure out how- JS: Which crowd do you- WR: Yeah, and part of that's very natural but some of it's also deliberate and I can't help it. I have a lot of anxieties about being someone that's- Anxiety is not necessarily the right word, but as someone who grew up in the mountains but is not from here. I am, I was born in Spruce Pine Hospital, I never lived anywhere else. I lived in Winston-Salem for a year and that's the only time I've ever not lived in mountains somewhere in Western North Carolina. Whether it was Boone or here, I've always lived- Thank God I'm moving to Lenoir! It's still in the mountains. [laughter] There's, like I've said before, a kind of anxiety around where am I really William Ritter 11 from cause I can't be as from a place as the people who an go back seven generations in a way. My parents being from off makes me talk a little bit different and have a different experience even though I went to a little baptist church. I had lot of very Appalachian experiences but I'll never be able to go all the way in. On the other hand, I'll never be able to be not a mountain person. I couldn't not be it either, so I kind of have a foot in both worlds, which I think is a good thing for trying to create community and breaching gaps between people that are different. That is something that means a lot to me. I don't know if it's because I grew up in the most Republican county in the state, but I am definitely not a Republican but I also think I have a different understanding for why people have those perspectives. I am always trying to create enriched community. Community is breaking down more and more and more, and it's like a buzz word. People just "ughh community," but there was a time when you weren't all necessarily cautious about community because it was just something you need to sustain us and communities were kind of more insular just cause you were smaller. You couldn't bus[26:59?] new people in your community and you had all these rich networks and it was vibrant, like an ecosystem's vibrant. Now it's very diluted and people move around a lot and so I think there's a lot of separation. Then there's, in contemporary times, I think Facebooks is mostly to blame for serious political divisions somewhat on socioeconomic and racial divides. I always feel like I'm in a good position to build community. I like meeting people and I like trying to bring people together that share skill sets but maybe have different perspectives. That matter's to me a lot. JS: I have a couple things going off from that. Being someone who is from the mountains but kind of also isn't, which I kind of get. I'm from the Chattanooga area and so we're technically part of Appalachia but a lot of people are like, "you're not really- WR: Oh yeah, oh yeah. You're urban Appalachia. JS: I from the Georgia side where it's like we're in the valley. WR: So you're on the other side of the river? William Ritter 12 JS: Yeah, I'm on the other side of the state line and so they're like, "luum."[Laughter] So have you ever run into obstacles because of that? Working with the community in that way. WR: I don't know that I have. I've been pretty fortunate. It's possible that I have and I'm ignorant that I was. I don't think that I have directly fallen to or had that get in my way. I think there have been times where, in a way, I felt, I don't think it was necessarily fair I even feel this way that I've been overlooked sometimes. In terms of what I might be able to offer as a traditional musician because I have a Master's degree and I really don't feel like it was that affluent of an upbringing but in some ways it was. Compared to a lot of people in this world it was, I think affluency is interesting to gage. My parents stayed together and we're financially secure. We never went on vacation or anything, we never had money for stufflike that. On the other hand, there were a lot of things, these are all things a lot of other people don't have and that is it's own level of affluency. If that answers your question. JS: Definitely. I'm going to circle back around to when you were talking about performing for different communities or audiences. Do you ever feel that there are different reactions between the two? Or do they take in the music a different way? Do have different kinds of conversations with different audiences? WR: Yeah, oh for sure. For sure. Though it's a tricky thing with music, any kind of performances, especially in theater, you'll have a crowd one night. Let's say you have a full house and for whate'ver reason they don't find the jokes in the play funny and, as a performer, people try to push it harder. Say the punch line in a way that's like how can you miss this? Then, it's like [cricket chirping 31 :06]. That certainly happens to a degree and it's always hard to gage William Ritter 13 how an audience will respond. I play at this place called Cataloochee Ranch, which I've played at for years and I love it. A lot oftimes I have really good experiences, but sometimes the audience, I feel like, as much as I try they're not going to get it. They're going to be like, "why are you singing in that weird way that you're singing? This is just kind of weird, I'd really rather listen to this other kind of music." I've had situations where I've played for people and I felt like their musical concept was so iPod or iPad based that they didn't necessarily see the humanity in me or the music. The thing that really bothers me is if I'm singing at a wedding or whatever it is and someone will just start talking; making an announcement and we're still playing a song. Why wouldn't you wait til we were done and be like, "I'm going to make an announcement." Otherwise I feel like you're going to turn me downlike a radio or stop in the middle of a song. That makes me feel that they don't get it in a way. Sometimes I'll play for a group, I primarily play as an old time musician and I'm not sure if you're familiar with the kind of division between old time music and bluegrass. But anyways, old time music is sort of like pre-bluegrass music I guess you could say. It's a little more tune based. *32:56-33:15: Interviewer and Interviewee determined to pause the interview to relocate due to increase in background noise caused by a weekly trivia night event. JS: Interestingly enough, my next question was looking at your thoughts on Appalachian stereotypes, which we kind of got at a little bit and the thought of outsiders. I'm just curious as to your thoughts on it. I know it's a big one. WR: It is a big one. It's very layered. There's a lot of nuance to how I feel about that, and also another part of that backdrop is I'm not just someone who grew up in the mountains. I was born in the mountains, but was also born of outsiders. I also have a Master's degree in Appalachian studies so I was very indoctrinated in a whole academic culture that, in many ways, William Ritter 14 sprung out of people trying to fight back against Appalachian stereotypes. That's very much still at the center of it; how we are breaking down stereotypes. I think they're nothing like they used to be. I really think that those stereotypes, and maybe I'm a little bit- I almost very rarely run into people saying demeaning things about mountain people. Like someone from Florida being like, "oh, you know, mountain people blah blah blah." I rarely hear that and it's not good when I hear that cause it makes me really mad. [laughter] I don't hear that as much, more I hear about people when thinking about the mountains they're like, "oh they're so beautiful." A lot of that kind of stuff, or a lot of positive things like, "oh I just love the mountain culture. Just the pace of life there is so nice. Just not like the rat race." [laughter] The stereotype thing, I think we've com such a long way and I don't think people put on caricatures like they used to and I don't think people are ashamed of being form the mountains as much anymore. It's such a different thing than it seems, how I perceive it, reading about how people were received as being mountain people in the past. A lot of that's really changed. That's not to say I don't occasionally have someone maybe say something that I'mlike, "that's just not fair to say." For example, there's a square dance caller that I did some shows with and he's a good caller and does a lot of really good storytelling. Anyways, he's telling a story and I felt like it kind of verged on a caricature of mountain people or hitting on themes that I felt like were really over blown like the moonshining and stuff. I personally know moonshiners, it's something I feel a lot of those things get overblown. On the other hand, I feel like there's a whole- in Appalachian studies they've gone so hard on the antistereotype train that they literally have made a stereotype of anti-stereotyping, that's very meta. One of the terms they used a very lot was, "oh the myth of this Appalachian thing." The myth of this, the myth of that. They're busting up these myths, but then people I think misconstrued that. William Ritter 15 Its saying like, "oh that's a generalization," is what I wish they would say. I wish they'd say, "that's like, people are taking that generalization and making assumptions about people as a whole." That's not really fair, not everyone does that. That's a generalization when you do that, when you think everyone ... what's a really cliche example? Everybody's got like three dogs living under their porch. That's a total generalization. On the other hand, I know a lot people that have three dogs. In Jackson county it used to be a status symbol, how many dogs used to run out from under someone' s porch when they came to great you. I think the fighting stereotype can go really far and I get frustrated when people say, "oh, well that's a myth." And I'm like, "don't tell me it's a myth. I grew up with it! I know what I'm talking about. Don't tell me what is and what is not Appalachia." You're aloud to say that's a generalization and you're aloud to say that's not always true, or everyone thinks that, but there's exceptions is totally different than saying that's a myth. I personally knew that myth thank you very much. That's just not fair to say that. On the other hand, saint that Appalachia is this rural experience is not always true. There's Chattanooga, there's Asheville, there's Birmingham, there's all these, Charleston, there's urban Appalachian places. Their Appalachian, a lot of the culture came from rural areas that moved to urban centers. There's urban Appalachia in Detroit. There's urban Appalachia in in D.C. it's kind of diffused somewhat, kind of become part of the melting pot, Cincinnati. It's there and it's not fair to diminish that in any was as being less Appalachian. I think that's just ridiculous. JS: Kind of going off of that. Liar's Bench that goes on at the university. What are your thoughts in general? What is Liar's Bench to you? What is its role in the community? WR: One thing that I really appreciate about Liar's Bench is that it's free to people that want to come every week. There's not any kind of price point. I appreciate that it's like going to church in a kind of way. It's like, "pay what you feel." It's like putting a tithe, you're supporting William Ritter 16 it on whatever you feel comfortable supporting it. I appreciate that aspect of Liar's Bench a lot. I think it's apart of its appeal. People are like, "oh you can go a thing for free," and then when you decide you want to maybe give some money to it you can, but it's not like you have to have five dollars to go in the door. It's a variety show, which I think is neat. You can kind of break up some of those generalization I'm talking about, the myths, by having a very traditional storyteller in terms of Gary Carden. He's a performance storyteller, he's definitely got a little bit of Jonesboro in him if that makes any sense. Jonesboros had the national storytelling festival; it's a very high art of storytelling and Gary is one of the best at that. He's really good at it. He's also a great story teller person-To-person, like old style kind of storytelling when I think about it. It can offer both of those things, he could get up, especially when his health was a little better, and tell one of those stories. Get Loyd Arneach to tell a Cherokee story. You could get someone, a local person, to get up and sing an original song that might have nothing to do with Appalachia but they live here so they're Appalachian. In that way, it's this neat kind of fusion of all these different things, which I think is really neat and appealing and I don't think we necessarily have enough of that. I really appreciate for that. Unfortunately the Liar's Bench is kind of not right not, I wish it was. [41:20] JS: You've done several performances on campus for different campus event whether it be Mountain Heritage Day or other kind of things. What are your views on those? What is your purpose? That's probably not phrased the best way, but what do you see those performances specifically with the university? WR: When I went to school at Western I think it was very formative when I could go to Mountain Heritage Day and see all these musicians and performers. That was very formative. I have this hope and dream that I'll play on campus and some kid will be like, "what is this music? William Ritter 17 I love it. I want to do this." Then they'll fall down the rabbit hole and they'lllearn to play old time fiddle. So there's definitely that going on. I definitely have a place in my heart for Western and I love to share Appalachian culture there. Partly because, I remember student orientation and they asked where different kid were from and they were raising their hands and were like, "Charles Mecklenburg area," and I was like, "woah!" Most of the kids there were from Raleigh or Charles Mecklenburg or from places where the most of the population of the state is. There's a lot of people coming up here and I want them to know more about mountain culture than what cliches they know and more about it than great hiking, or great rafting, or good beer. I would like them to know about the culture here if they don't and hope that they fall in love with it. That's definitely a thing is try to help people see that, maybe get into it and perpetuate it, even as an outsider, but make their own way into the culture through the avenue of music, which I think is a great way to learn that kind of music or even tell old stories to make end roads. I think music's always been a great way for cultures to come together. You know, black and whites could play music together, they might not record together, but it was one of the few places it was really super okay to be together and to share something was music. I think that's still true. You can have a. Jewish guy from Brooklyn come down and play old time music with a guy who's eighth generation mountain person. I think that's a really cool thing. JS: Just to get your opinion, I am also going to be interviewing Gary [Carden] and Susan Peppers. I don't know if you know who ... WR: I do know Susan. JS: Yeah, Susan. Is there anything that I should ask them about? I'm going to be asking them some of the same kind of questions. William Ritter 18 WR: I think the questions that you have are really good, open good doors for conversation. Just thinking in the terms of us three, that's an interesting trio because Gary's very much from here, born here, family here. On one hand though, I think in someways he was always a little bit ostracized by his community, which, if you look at the tradition of the "fool" in history. You're valued in your community for what you have to offer but you're also kind of made an outsider as someone who is kind of weird and in touch with something than other than everyone else; and that's just the concept of the fool. I think Gary's fits into that in someways. I don't think that he's a fool I'm just saying that narrative kind of fits and I think that he has some anxieties about his insider/outsider-ness as an unusual, artistic kind of dreamer. A young person in the mountains that had an interest in folklore and drama. Susan, on the other hand, she could tell you more, is an outsider from what I understand. I think she grew up somewhere up north. Everything is up north from here. She also very much identifies, I think, with the music and came to love it and use that as an in-road to be a part of this particular layers of the culture. And me being a person who's born here but my family's from here, so there's three different views. [47:02] END OF INTERVIEW Transcriber: Janie Stallings Date Transcribed: 11/26/2018

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

William Ritter, an Appalachian musician, discusses his experiences performing, songwriting, seed-sharing, and connecting to the community through Appalachian music. This interview was conducted to supplement the traveling Smithsonian Institution exhibit “The Way We Worked,” which was hosted by WCU’s Mountain Heritage Center during the fall 2018 semester.

-