Western Carolina University (21)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- George Masa Collection (137)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2900)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (422)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (85)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6797)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (153)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- 1700s (1)

- 1860s (1)

- 1890s (1)

- 1900s (2)

- 1920s (2)

- 1930s (5)

- 1940s (12)

- 1950s (19)

- 1960s (35)

- 1970s (31)

- 1980s (16)

- 1990s (10)

- 2000s (20)

- 2010s (24)

- 2020s (4)

- 1600s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 1910s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (19)

- Asheville (N.C.) (11)

- Avery County (N.C.) (1)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (55)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (17)

- Clay County (N.C.) (2)

- Graham County (N.C.) (15)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (40)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (5)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (132)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (1)

- Macon County (N.C.) (17)

- Madison County (N.C.) (4)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (1)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (5)

- Polk County (N.C.) (3)

- Qualla Boundary (6)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (1)

- Swain County (N.C.) (30)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (1)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (3)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Interviews (314)

- Manuscripts (documents) (3)

- Personal Narratives (8)

- Photographs (4)

- Portraits (2)

- Sound Recordings (308)

- Transcripts (216)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Bibliographies (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (0)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Exhibitions (events) (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newsletters (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Notebooks (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Publications (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Relief Prints (0)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- African Americans (97)

- Artisans (5)

- Cherokee pottery (1)

- Cherokee women (1)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (4)

- Education (3)

- Floods (13)

- Folk music (3)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Hunting (1)

- Logging (2)

- Mines and mineral resources (2)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (2)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (2)

- Storytelling (3)

- World War, 1939-1945 (3)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Maps (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Sound (308)

- StillImage (4)

- Text (219)

- MovingImage (0)

Interview with Norma Kimzey

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

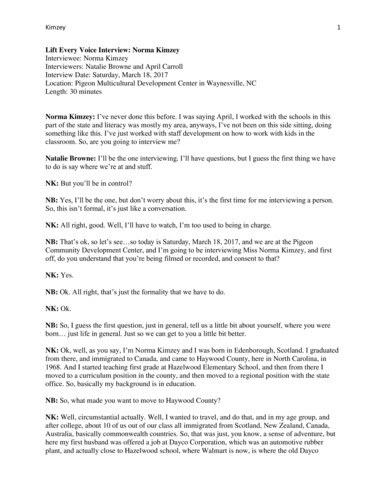

Kimzey 1 Lift Every Voice Interview: Norma Kimzey Interviewee: Norma Kimzey Interviewers: Natalie Browne and April Carroll Interview Date: Saturday, March 18, 2017 Location: Pigeon Multicultural Development Center in Waynesville, NC Length: 30 minutes Norma Kimzey: I’ve never done this before. I was saying April, I worked with the schools in this part of the state and literacy was mostly my area, anyways, I’ve not been on this side sitting, doing something like this. I’ve just worked with staff development on how to work with kids in the classroom. So, are you going to interview me? Natalie Browne: I’ll be the one interviewing. I’ll have questions, but I guess the first thing we have to do is say where we’re at and stuff. NK: But you’ll be in control? NB: Yes, I’ll be the one, but don’t worry about this, it’s the first time for me interviewing a person. So, this isn’t formal, it’s just like a conversation. NK: All right, good. Well, I’ll have to watch, I’m too used to being in charge. NB: That’s ok, so let’s see…so today is Saturday, March 18, 2017, and we are at the Pigeon Community Development Center, and I’m going to be interviewing Miss Norma Kimzey, and first off, do you understand that you’re being filmed or recorded, and consent to that? NK: Yes. NB: Ok. All right, that’s just the formality that we have to do. NK: Ok. NB: So, I guess the first question, just in general, tell us a little bit about yourself, where you were born… just life in general. Just so we can get to you a little bit better. NK: Ok, well, as you say, I’m Norma Kimzey and I was born in Edenborough, Scotland. I graduated from there, and immigrated to Canada, and came to Haywood County, here in North Carolina, in 1968. And I started teaching first grade at Hazelwood Elementary School, and then from there I moved to a curriculum position in the county, and then moved to a regional position with the state office. So, basically my background is in education. NB: So, what made you want to move to Haywood County? NK: Well, circumstantial actually. Well, I wanted to travel, and do that, and in my age group, and after college, about 10 of us out of our class all immigrated from Scotland, New Zealand, Canada, Australia, basically commonwealth countries. So, that was just, you know, a sense of adventure, but here my first husband was offered a job at Dayco Corporation, which was an automotive rubber plant, and actually close to Hazelwood school, where Walmart is now, is where the old Dayco Kimzey 2 Corporation was. So, that was a plant that probably had about, maybe, 2,000 workers. And my first husband was a chemist. So, that caused us to move to North Carolina. And another reason for doing it was from the cold, cold winters in Canada to a beautiful western North Carolina. I love four seasons. NB: So very true. So, you’ve been all over the place then. So, you taught first grade at Hazelwood Elementary, and I understand that you knew Ms. Osborne. Did you know her from teaching there, or did you know her previously? NK: I just knew her from teaching there. NB: Ok. NK: And, ok, I had first grade, and when I came, this was 1968. So, a year before that, Haywood County schools consolidated. That was the word that was used, in fact, when I interviewed, I asked why was it called Haywood County consolidated schools, and it was explained to me that the schools had integrated. And now I might just preface the next part by saying, when I grew up in Edinburgh, and went to university there, Edenborough medical school had loads of students from Ghana, Nigeria, and just really from all different parts of the world, so I’d always just been exposed to different people. So, when I came to North Carolina, came to Haywood County, everybody in the school was white, and everybody in the school was white, except for Ms. Osborne. And she taught second grade. So, it was, I just wanted to, you know, see how is this. What has caused this? Well, really what happened was one school, in fact, here where we are right now, Pigeon Street School, was for African-American children. And so, when it closed in 1967, and when Tuscola and Pisgah high schools were built, so that high school kids went to either of the two high schools. But the people who had come from this school, for Haywood County, for all the children in this part of the county they were assigned to the school for their district. Which for this school typically was Central Elementary, not Hazelwood School. So, Ms. Osborne must have been assigned to Hazelwood School. So, my connection to her, and we had gone to a Martin Luther King, we go each year to Martin Luther King breakfast and a march, close to the day of Martin Luther King anniversary day, and I just happened to mention that I had known Ms. Osborne, and saw her as a gracious lady, who was the only black person in a school with five, six hundred kids, and a whole full white faculty. There was no diversity. So, and thinking back on how things were…you want me to go on and tell? NB: Go ahead. NK: We’re talking a long time ago, like 50 years. In first grade, there were five first grades, and sometimes six, and there would have been the same in second grade. And we each had about 30 kids, plus. And so, we were at the old Hazelwood School, what we call the old Hazelwood School now, which is now the Folkmoot Center, on Virginia Avenue in Hazelwood, and we took the kids out to the playground area which is really just a big grassy area out the back of the school. So, first grade I think we were out first, and second grade would come out too, and so, I would just chat to Ms. Osborne, and there was no big deal, you know, but I remember feeling and thinking, how would it be to be the only black person in all of this white environment. And my memories are, she was just very gracious. So, of the thing that I wanted to bring up about it all though, is when we would go to the lunchroom, the first graders went in first, we had no kindergarten back then, and so we would have our class line up and so on. And what I noticed there were fewer kids in Ms. Osborne’s class. And of course, we were all, what we called loaded with 30 plus kids. And one day, I just thought, well, I wonder what’s happening with that? And one day we were all out on the playground, and these first Kimzey 3 graders that I had they say everything and anything to you, and this little boy came up to me and he said, “My daddy said I’m not going in that lady’s class next year.” And I thought, that’s why she doesn’t have a full load of class kids. And there was no parent request for teachers at the school. We had a great principal, Mr. Evans, Robert Evans, very fair, very caring about kids, did bus duty every morning, greeted the kids to school. And, I think that just shocked me. And it was right in front of my face that we had parents in our whole school that didn’t want their children taught by a black teacher. So, at that time I was like 26, 27, I came home and talked to my husband about it. And, I think back, I talked to the principal about it, and he told me, and I think he was so wise, he said things, and see, I was an outsider, big time outsider. I think what he helped me understand, he said, “Things like this is going to take time.” And he said, you know, “I’m aware of it. I’m working on it.” And I said, “Oh I don’t doubt that.” Well, he worked behind the scenes. But, the next year, I taught for three years, first grade, and without getting into specifics of families, I had a doctor’s son, and a dentist’s son, and another doctor’s daughter, and what I noticed the next year is there was a higher number of kids in Ms. Osborne’s class. And there was, what I would call a good mix of children from economic backgrounds. And so, you know, it wasn’t just, and this sounds so, I don’t mean to degrade people, but often if families have too many things to worry about, they’re not thinking about who the teacher is then these kids tend to get put wherever. But I felt like Mr. Evans really worked at trying to get some equality in the school. And you know, I just think back to it, we’ve come a long way where I really feel in Haywood County, now, that’s not even an issue. NB: So, you don’t feel like Haywood County, now, you feel like that over time that’s kind of… NK: As far as school and children. Now, I’m not saying there’s not, there’s not prejudice. There certainly still is. And I’m sure you’ll talk to other people. You know, right now in 2017. But we’ve come a long way from, I think people saying, “My child’s not going to be taught by a black person,” and if they think it, they’re not going to say it. But, I think that things are much, much more equal nowadays. NB: So, you say that they couldn’t select which teacher they wanted to go to. So, if they don’t want their students to go to the second grade, where did the students go? NK: Well, they…I don’t know. NB: You don’t? NK: You know, so many kids were bussed to school, and then others were brought to the school, so at that time I don’t remember any other schools, you know, it was certainly way before charter schools or any other concept. And western North Carolina, we didn’t have private schools, which in eastern North Carolina there were many more private schools that were basically set up as white academies. But we didn’t have that in Haywood County. But I think now, I’m guessing this, I would guess our principal, if somebody came and said, “I don’t want my child in Ms. Osborne’s classroom,” I would venture to say, he should say, “OK,” or handle it like well, “I wish you would give it a go or give it a try.” But clearly that first year, that wasn’t, things were going on that I don’t know, I shouldn’t speculate I guess, but I think people could say no, but you couldn’t say who you would get. You know, so, follow me, in terms of choosing. NB: Yes. Kimzey 4 NK: Yes, like you could choose not to, but you couldn’t choose who you did want. And that was to keep people not thinking there were favorites and teachers and who was better than whoever, you know. NB: Exactly. NK: It gets complicated. NB: Now, did Ms. Osborne ever say anything, or, I mean, did she ever show any sort of sign about her feelings towards this or? NK: No. And I didn’t bring it up. NB: Right. NK: And we just, you know, it was just mostly chatting on the playground or in faculty meetings sit together. But, what I did notice with her, those kids, they loved her. I mean, they go off in first, second grade level, I think they’re still like that, they hug. You know, they were just a really good feeling with her, with the kids that she did have. NB: So, she, Ms. Osborne taught before the schools were integrated, right? NK: Yes, she was at the end of her career, toward the end of her career. Yes, because I know she was there the three years I was there at Hazelwood, but I would say, and you’ll have to check with others on her age, she was probably in her fifties or so, when I knew her. NB: Gotcha. NK: I don’t know how long she had taught here at Pigeon Street. NB: So, she taught at Pigeon Street? NK: I’m pretty sure she did, yes. Yes, because I think Annie McAdams, I think she had Ms. Osborne. We were talking about this at the breakfast, the Martin Luther King Day. So, you might, you might check with her. NB: OK, I definitely will have to go and ask her about that. So, I guess I’m asking more something about you. You say that you came from Scotland, where it is a lot more diverse compared to here. Was there one thing that when you came to Haywood County that was shocking to you, that, like the diversity differences. You have like, any memories? Just in general or, anything? NK: Well, I think my perception had been movies, American movies, and not all of Scotland, that is totally different now because so many people have migrated there from Pakistan, and India, and other countries, as well as African countries. So, it was Edenborough where I lived and went to college where the diversity was, you know, because it was the student population, not young students, but graduate students, you know, who were there for medical degrees and so on. So, coming to this country, I had always thought that America was as diverse as I saw in the movies, or saw, I guess, your people over there thinking everything is like New York or Miami. So, I was surprised how white Haywood County was, and so few African-Americans here. Kimzey 5 NB: Yeah, I mean that’s good. Thank you, and so, I know Ms. Osborne was the only African-American teacher at Pigeon…I’m sorry, at Hazelwood, did you know any other…were there other African-American teachers, that, you know, in other schools after the consolidation, integration, or? NK: The only other person I knew, and this was when we’d have like, a meeting of all levels. And Mr. Eggleston was African-American, and I think he, you know, I mean it was so obvious to see two or three teachers in the whole system. NB: Wow. NK: But Mr. Eggleston was secondary, you know, high school level. April Carroll: What about students, what happened to all the students that were at the Pigeon Street, that were consolidated, where did they go? NK: Yes, they went to Central Elementary. But see it was, it was something like, I don’t know if it was even one percent of the population, so we’d be talking about, you know, 20 kids, 30 kids. But they were not at Hazelwood. AC: Were they perceived the same way as Ms. Osborne, were there were people in the community like, “my children are not going to…” NK: I would, I would imagine because this was in the era of George Wallace, in Alabama, was standing there as governor, you know, stopping people. This is, you know, the era of Ruby Bridges, you know, where people didn’t want a child in a white school. So I don’t know, you may want to talk to Pat Bryson. She has retired from Central School now, and is African-American. She is the next generation down, you know, she’s a bit younger than me. But she would be able to give a perception of Central School, more. NB: Ok, and I believe her full name is Pat or Patricia? NK: Patricia. NB: I believe we actually are interviewing her. NK: Ok, good. NB: Later on, I think in April. NK: OK. NB: We have her on the list to be interviewed. NK: Well, she, she retired and she asked, she might still sub and do some work. I met her a while back, and she was still doing some work in schools. But she taught a long time at Central Elementary. But not way back in ’68, you know when the first group of children were integrated. See, I’m just talking at one elementary school where they would go to, in this part. The other children in eastern Haywood, I would say…would have gone to North Canton School. But North Canton was Kimzey 6 not built then, it was Beaver Dam, and it was Penn Avenue. So, that’s more than likely from the Dutch Cove community in Canton, they would go to Penn Avenue and I just wasn’t aware. You know, I just wasn’t part of all that. NB: And I don’t know if you know this or not, you know, or were aware, of like, were there any differences between, after the schools were integrated, like the quality of them before, like before integration, the African-American schools versus, after, did you know anything about that or aware of anything about that, you probably weren’t here yet. NK: No, but I know Ann can talk about the differences because she’s shared that with me. That, you know, that they didn’t have the children at this school did not have the textbooks, and the materials. They got in hand-me-downs in materials. But, now I do know Mr. Evans made sure Ms. Osborne had everything that everybody else had. He has passed on, but you know, I just think back on there was a good many…some good folks back in the days when they knew how to make a difference, you know, in quiet ways. NB: And did Mr. Evans, did he stay at Hazelwood, or do you know? NK: Yes, he retired from Hazelwood, and he taught at Crabtree. And it was a secondary school, and he taught what people would call shop. So, he, he really knew how to work. And so, you know, Crabtree, I live there now, and he would, we would talk standing out there in the bus duty, and he’d tell me about it, he said, “I had all the farm boys,” you know, and he said they just wanted to know how to fix tractors and things, you know, so it was a big shift for him to come from that background. But, see that was a K-12 school, Crabtree School was, all the schools, you know, back…but that’s a whole other project isn’t it, the schools of Haywood County. But he came as principal, or maybe, or he probably came when the consolidation…I hadn’t thought of that, because see, when they built Tuscola high school, that caused all of the small schools to have all their high school kids come to either Pisgah or to Tuscola. NB: OK. NK: So, you know, Waynesville Middle School…Waynesville Junior High, that used to be Waynesville High School. It was the high school there. NB: OK. NK: And on that campus where the football field is, down on Brown Avenue. NB: And you said, is it Mr. Engelstine or Eggleston? NK: Yes. NB: Did you know what he possibly taught, or what he did? NK: No, I’m not sure. But he was the same era as Ms. Osborne because I know the scholarship for young people, as part of the Martin Luther King project, is named for Osborne/Eggleston Scholarship. NB: OK. Kimzey 7 NK: So, I’m sure you can, you know, again, you could talk to people of Anne’s generation…she would know better. NB: Ok, so…I believe that’s about all the questions, we have one more. AC: We have one more question and this is just something that we’re kind of investigating, behind the scenes on this. But demographically…we’re looking at the demographics of the area, and demographically speaking there were, there was, Reynolds School and this school, that were the African-American schools…and we’re just noticing from then until now, they all integrated into these schools, but now demographically…my daughter goes to Waynesville Middle School. There’s one African-American girl in her entire class, and her sister is in sixth grade, I believe now, they’re the only two African-American children in their entire school. And their parents moved here, they are doctors from Haiti or something. So, we were just wondering demographically, was it so hard integrating into this community that they left, like we were just wondering if you had any insight. NK: I’m just, I’m trying to think…we know…my husband and I are in the NAACP local chapter, well national, but local, and the generation, the people I see who are African-American here now are people like Lynne Forney. And see, Tasha, she’s college age, so, I think it’s just there are no more, and there’s just like three or four families left…Gibbs, Forney, Phil Gibbs. There are no young children in Waynesville. Now, if you go to Canton, there are families there, you know, through the generations. But I think you have to ask someone like Lynne. AC: We just find it fascinating that it went from… NK: Yes. AC: …two schools, to there’s no one…because we moved here, my husband is retired Air Force, so my children are used to… NK: Yes. AC: …diversity and we moved here, they’re like, “Where’s all the different people mom?” They were confused on that I find it fascinating the whole demographic. NK: I would just say [they] moved, but, you know, and of course we always have to watch not to speculate but, Haywood County, and I didn’t really realize…it’s just been so gradual…Haywood County’s lost, since I came, I want to say six or seven industries. There was Unagusta, um…I can’t even name them all, but you know, they employed a good number of people. And when they closed, then what would happen is people just moved, you know. So not necessarily moved to Asheville, but moved, like Dayco had a plant in Ocala, Florida. They had African-Americans working in the plant, as, and, as part…when I was here, but you know, where they moved, you see Dayco closed, what…20 years ago. So, it’s not just like recent times where people have moved, and I just can’t even think of young children. And the families I know that are African-American here, Lynne’s were the last, that is what I would say. They have a son, but I want to say Tuscola school age. He’s, he’s probably a junior, senior in high school. And Tasha is college age. So, I don’t know any other black children, and they, you know. AC: That demographic is just very odd. Kimzey 8 NK: Yes, Yes, so, but I can, I think that’s a good question. I mean obviously, it’s a good question. But, I would think, I keep going back to people like Lynne and Anne McAdams. Phil Gibbs, have you got him on your list? NB: I believe so…I think there’s a Gibbs. If it’s not him it might be his wife. NK: Gibbs is Lynne’s family name, Forney is her, and Forney’s are also in Canton. Her husband’s from the Canton group of Forney’s. NB: So, there may have been other reasons why people left, like economics. NK: Yes. NB: It might not have been just purely due to, that integration of African-Americans. There might be other reasons for that. NK: Right. NB: Is there anything else that we haven’t discussed yet that you’d like to ad, or anything, that it doesn’t necessarily have to be about this…anything you would like us to know? NK: I just think at the, at the time when Haywood consolidated, that was late so to speak, 1968. But I think to build, Haywood County had a good concept of building new schools, and I think what that did, it, it shifted and pushed things along so that all children were getting better facilities. You know, I think a lot of people when it comes to race, they think it can get fixed by everybody has good books, and you know, nice classrooms, which is fine, everybody should. And I think Haywood worked on that. You know, like North Canton was a new school, so they closed the old schools where, and of course they closed Reynolds…way back when they closed this Pigeon Street. But they can, Haywood, the school system continued to work on facilities, you know, which pushed us to more integration at the time. But see, there were so few African-American families in Haywood County to start with. But it didn’t matter if there was two, or three, or one, or twenty. We need equal education for all. NB: Thanks so much for coming out today and sharing your stories. Especially about Ms. Osborne, and just your own personal experience with this, whole integration process, especially from your point of view from someone out, coming in. It’s been a very good point of view, something we probably wouldn’t have gotten from anybody else, so we thank you so much for coming out and doing this. NK: Thank You. END OF INTERVIEW

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Norma Kimzey is a Scottish immigrant who came to Haywood County in 1968. She taught first grade at Hazelwood Elementary School and remembers Ms. Elsie J. Osborne fondly. After the consolidation of the Pigeon Street School, Ms. Osborne was assigned to teaching the second grade at Hazelwood Elementary School where she was the only African American teacher in a school of 500-600 children. Coming from a multicultural atmosphere in Scotland, the primarily white demographics of the segregated South came as a cultural shock to Kimzey. She recalled, "I remember feeling and thinking how would it be to be the only Black person in this all-white environment...there were fewer kids in Ms. Osborne's class, and of course we were all loaded with thirty-plus kids. One day, I just thought 'Well I wonder what's happening with that?’”

-