Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (24)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Champion Fibre Company (5)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (23)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (17)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Stearns, I. K. (2)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (45)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (55)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (72)

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (0)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (0)

- Brasstown Carvers (0)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (0)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (0)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (0)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (0)

- Cherokee Language Program (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Crowe, Amanda (0)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (0)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (0)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (0)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (0)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (0)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (0)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (0)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (0)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (0)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (0)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (0)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (0)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Roberts, Vivienne (0)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (0)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (0)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (0)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (0)

- USFS (0)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (0)

- Western Carolina College (0)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (0)

- Western Carolina University (0)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (0)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (0)

- Williams, Isadora (0)

- 1810s (1)

- 1840s (1)

- 1850s (2)

- 1860s (3)

- 1870s (4)

- 1880s (7)

- 1890s (64)

- 1900s (294)

- 1910s (227)

- 1920s (461)

- 1930s (1585)

- 1940s (82)

- 1950s (15)

- 1960s (13)

- 1970s (47)

- 1980s (14)

- 1990s (17)

- 2000s (31)

- 2010s (1)

- 1600s (0)

- 1700s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 2020s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (80)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1)

- Avery County (N.C.) (6)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (159)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (204)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (10)

- Clay County (N.C.) (3)

- Graham County (N.C.) (108)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (416)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (263)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (13)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (58)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (21)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (11)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (25)

- Madison County (N.C.) (14)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (5)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (7)

- Polk County (N.C.) (2)

- Qualla Boundary (22)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (16)

- Swain County (N.C.) (516)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (36)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (2)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (34)

- Aerial Views (3)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (4)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (77)

- Drawings (visual Works) (174)

- Envelopes (2)

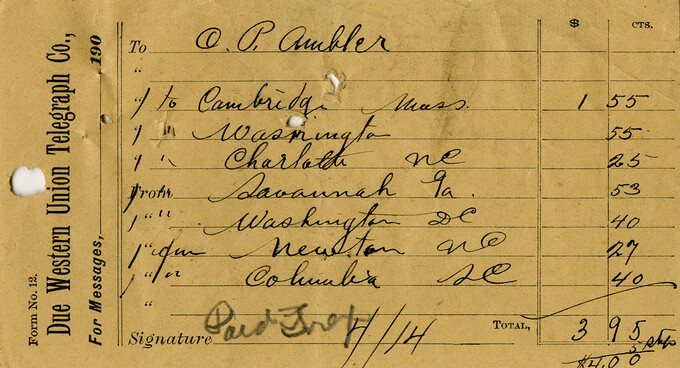

- Financial Records (9)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (34)

- Guidebooks (1)

- Interviews (11)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (219)

- Manuscripts (documents) (91)

- Maps (documents) (69)

- Memorandums (14)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (20)

- Negatives (photographs) (282)

- Newsletters (12)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Photographs (1657)

- Portraits (39)

- Postcards (15)

- Publications (documents) (107)

- Scrapbooks (3)

- Sound Recordings (7)

- Speeches (documents) (11)

- Transcripts (46)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Personal Narratives (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (282)

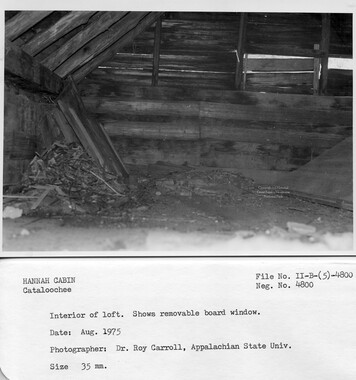

- Cataloochee History Project (65)

- George Masa Collection (89)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (126)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Jim Thompson Collection (44)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Map Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (10)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (107)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (0)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Appalachian Trail (22)

- Church buildings (9)

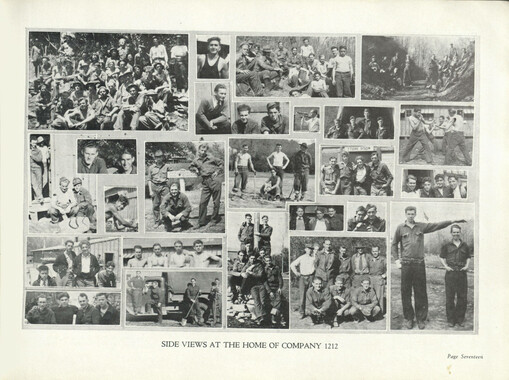

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (91)

- Dams (21)

- Floods (1)

- Forest conservation (11)

- Forests and forestry (42)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (64)

- Hunting (2)

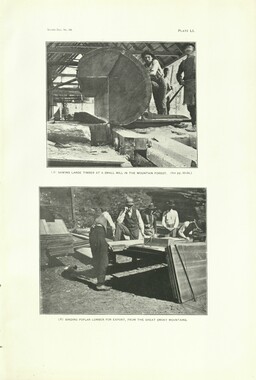

- Logging (25)

- Maps (74)

- North Carolina -- Maps (5)

- Postcards (15)

- Railroad trains (8)

- Sports (4)

- Storytelling (2)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (39)

- African Americans (0)

- Artisans (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Cherokee pottery (0)

- Cherokee women (0)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (0)

- Dance (0)

- Education (0)

- Folk music (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Mines and mineral resources (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- School integration -- Southern States (0)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- Slavery (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- World War, 1939-1945 (0)

- Sound (7)

- StillImage (2172)

- Text (655)

- MovingImage (0)

Indian Fair in The High Road

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

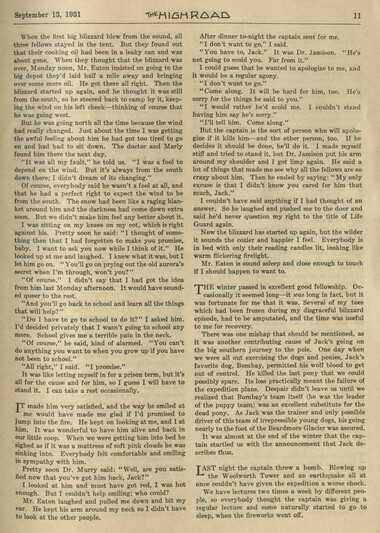

-^HIZjHRAAL^ September 13, 1931 the wedding, and three weeks and a half since the bride and groom had returned from three days in Boston to find Jen harboring the young stranger. "This," Jen had said, closing the oven door, "is Barbara, Ed. Barbara Searles, you know. She came the day you went away. I told her it was too bad she hadn't let you know, or you could have planned to be at home, but, as it was, we've managed to comfort each other, haven't we, Barbara? There, go into the front room and leave your things where they won't get scented up with the cooking. You'll stay to-night with us, won't you?" T TSUALLY Jen was not one with much to say, but that night she had hardly been silent a minute unless some one else was speaking. Ed and Margaret, too, recovering their courage, had talked gallantly. Even Mark Shaw had searched his memory for stories to tell. Only Barbara had been uncommunicative, had sat for hours that night and rode between Ed and Margaret to their new home, the next day, her hands folded and her face cold and secretive. She had remained so ever since. Margaret knew her no better than when she had first met her, and was full of forebodings. It is queer business living on a farm with a stranger. The queerness of it loomed larger and larger between Ed and his wife. Jen noticed it. Even Mark Shaw noticed it. "It seems like Ed and Margaret can't hardly see each other for that Searles girl over there," Mark Shaw said one night at supper. "I know it," Jen answered. "They pay too much attention to her." "She'd get along better if she had more work to do," Mark Shaw observed. He believed in work. "She'll straighten out when she gets her mind made up to it," Jen said. "It's all new to her here, of course. They ought not to pay so much attention, but just go along about their business." TT was not as if Ed and Margaret had not tried to do this, but Barbara Searles was too vivid an element to be overlooked in their quiet lives. She was too strange, too beautiful, and too strong in her proud, silent way to be overlooked even in a farmer's springtime. Her presence filtered through everything. When she was present, they were acutely conscious of it. When she was absent, they talked about her. This was partly due to Barbara's personality, but even more to the fact that they had little else so specific about which to think. Farming, teaching, plans, memories, and wedded love are live coals; Barbara was a flame— silent, sullen, threatening, but still a flame. The day which Ed and Margaret spent at planting, as Jen had suggested, was almost a success. Down under the hill in the north field not even the chimney tops of the house were visible, nor the ridgepole of the barn. Violets grew all along the edges of the plowed field. Birds sang in the marshes. The air was sweet. Margaret walked first, dropping corn, and-Ed followed dropping beans. She could feel him, tall and steady, behind her. Sometimes he spoke. " There goes a blue bird!" After two rows, he set down his pail of beans and began covering what they had planted. Margaret liked the sound of the metal moving the soil. "Tired, puss?" Ed asked her. She smiled and shook her head, but he put his arm around her while they rested for a minute in the sun, and she leaned against him. "0, Ed," Margaret said, "I am happy!" Ed only grinned and did not speak, but he was happier than she. This was life as he liked it—everything simple and in its place; nothing standing apart and looking on. '"THEY ate their lunch in the shade of a big walnut tree on the side hill. There were biscuits with home- cured ham between, hard-boiled eggs, Jen's gingerbread, and lukewarm tea with milk in it but no sugar. When they had finished, Ed lay for a while with his head on Margaret's lap. "Sing me a tune, why don't you?" he asked. "O, I couldn't," Margaret told him. "Somebody might hear." "Say one of your poems, then." "0, I couldn't." He imprisoned her wrists. "Say one!" She said the first lines she could think of, pink from his gentle bullying. "The lark's on the wing, The snail's on the thorn, Morning's at seven; the hillside's dew-pearled. God's in his heaven— All's right with the world!" "I'm not quite sure that's right, Ed!" Margaret had not had much time for memorizing more than rules of grammar and arithmetical formulas. "It's good enough," Ed told her. "I know what it means all right. That's what poetry's written for as much as anything else, ain't it?" "I guess so," Margaret answered shyly. It was good to have Ed ask for and comment on poetry. They walked back to the plowed land and worked there all afternoon. It was a large piece but before sunset more than three quarters of it was seeded down. "I can finish it Monday, if the weather's fine," Ed said. They went up the hill side by side. Ed wheeled the hoe and left-over seed in wooden measures on a barrow ahead of him. The grass was tall enough to brush Margaret's ankles softly as she walked. Carefully they followed the same trail they had taken coming down, not to make two tracks. The sun set in a burst of color, as it had the night before, and would the next night. "O, Ed," Margaret said, becoming aware of windows and doors which lay ahead, "I wish to-day weren't over!" Ed did not answer. He had seen the house sooner than she. '"THEIR pace did not slacken. Margaret kept close to Ed's shoulder, realizing for the first time how tired she was. The sky had turned a quick gray, as spring skies do. [ Continued on page IS ]

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

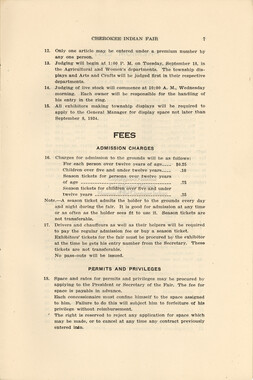

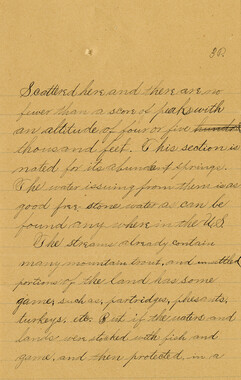

This article titled, “An Indian Fair” was written by Paul Fink and published in The High Road in 1931. The article appears on pages 7, 8, 9, and 14. The narrative begins with a brief history of the Cherokee people and concludes with a description of the annual Cherokee Indian Fair. Paul M. Fink (1892-1980), a hiker and advocate of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, served on the Tennessee Nomenclature Committee. Working with George Masa and others, he was largely responsible for routing the Appalachian Trail through the Great Smokies and nearby mountain ranges.

-