Western Carolina University (21)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (291)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- George Masa Collection (137)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (3182)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (422)

- Horace Kephart (998)

- Journeys Through Jackson (159)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (90)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (318)

- Picturing Appalachia (6617)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (153)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (738)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2491)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1463)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (91)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (2008)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (3032)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1945)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (200)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1680)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (556)

- Graham County (N.C.) (247)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (535)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3573)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4926)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (61)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (21)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (14)

- Macon County (N.C.) (421)

- Madison County (N.C.) (216)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (135)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (982)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (78)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2187)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (270)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (86)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Bibliographies (1)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (193)

- Copybooks (instructional Materials) (3)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Digital Moving Image Formats (2)

- Drawings (visual Works) (185)

- Envelopes (115)

- Exhibitions (events) (1)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (823)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1070)

- Manuscripts (documents) (618)

- Maps (documents) (177)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (6192)

- Newsletters (1290)

- Newspapers (2)

- Notebooks (8)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (194)

- Personal Narratives (10)

- Photographs (12977)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (6)

- Portraits (4573)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (181)

- Publications (documents) (2444)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Relief Prints (26)

- Sayings (literary Genre) (1)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (2)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Songs (musical Compositions) (2)

- Sound Recordings (802)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (18)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (329)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (564)

- Cataloochee History Project (64)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1482)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (36)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1923)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (390)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (190)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (114)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (2012)

- Dams (115)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (63)

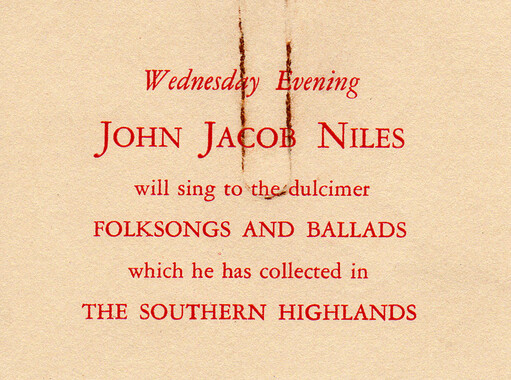

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (1198)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (181)

- Hunting (47)

- Landscape photography (25)

- Logging (122)

- Maps (83)

- Mines and mineral resources (9)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (72)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (243)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (174)

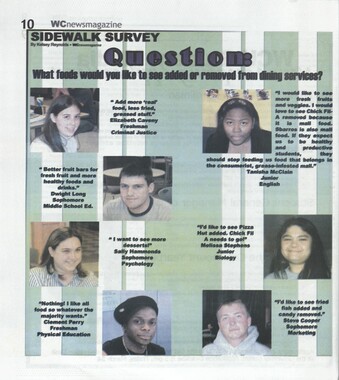

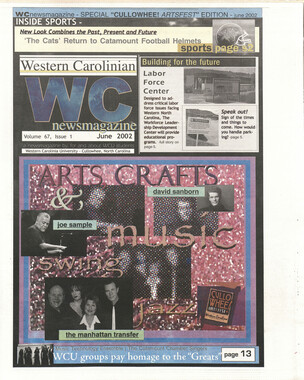

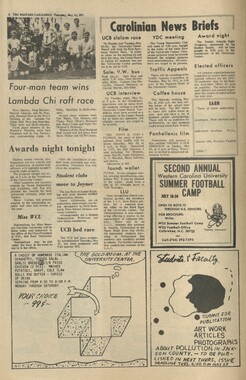

Western Carolinian Volume 44 Number 34

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

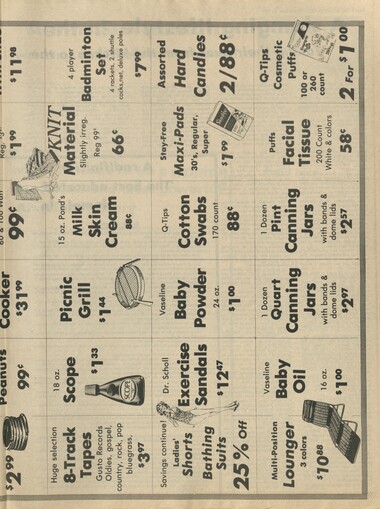

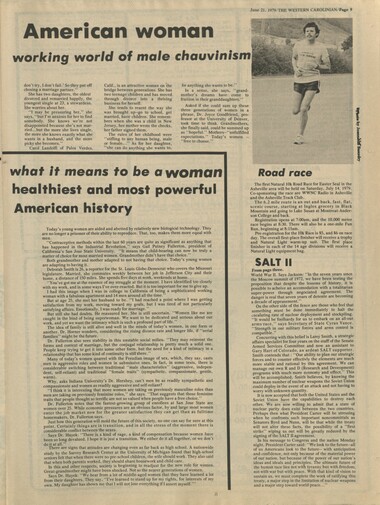

Page 8/THE WESTERN CAROLINIAN/June 21. 1979 A changing lifestyle in the Taking their lives from the kitchen to the From page 1. they worry as well-that their offspring may miss what they consider the joys of home and family. Tressa Eichenbaum of Austin, Texas, is 62, a child of the Depression and an older kind of bringing up. The rules were different in her young days. "My parents were strict disciplin- aries," she says. "They expected me to mind, to be courteous, honest, dependable, to tell the truth and observe whatever hours were my curfew." Grandmothers and mothers were brought up to orientate themselves around family first, then to move into the world. Their daughters are saying, "But I'm not going to wait. Why should I?" That, says Dr. Huyek of the Illinois Institute of Technology, leads to the quandary: "The mothers sometimes feel that the daughters haven't paid their species dues yet, parenting and taking care of the next generation." The differences, the similarities, both run deeper than that. To chart how far womanhood has come in the last 60 years, The Associated Press commissioned a demographic profile of the three generations. They speak en chorale of some of the threads and themes of female life today. Today's brave new woman is, after all, rooted in her mother and grandmother, the worlds they came from. Only 60 years ago, grandmother's world was remarkably primitive. She had one chance in 205 of dying in childbirth and one chance in 20 her baby would die. She could only expect to live 62 years at birth, and her husband considerably less. "In that era there were many family enterprises," says Dr. Gail Putney Fullerton, president of San Jose State University and a student of female lifestyles. "Many women would not show on the records as employed persons. They were unpaid family workers, perhaps a mom-and-pop grocery store, or maybe she ran the cafe and he pumped the gas at the diner at the bend in the road." Contraception was primative, too. Childbearing was often delayed for economic reasons. Combined with infant mortality, the result was that grandmother's generation produced only 2.2 children per women, barely over the replacement rate, and one of the lowest in American history, until now. Mrs. Lee Durham is 70, a retired teacher living with her retired husband in Overland Park, Kansas. She was 30 when she had her first child. She worked. "During the Depression I was teaching and my husband often couldn't find work," she remembers. "We had to wait five years to marry because we couldn't afford it." She made $135 a month and had a car. She quit when they were married. They had three children, and for 20 years she raised her family. Then she went back to teaching. She tries to understand a woman's world today: "I think by the time a young woman reaches 20, if her parents have given her a good moral foundation, she should be able to make a decision about living together and other things. Parents just have to accept thatr" But the ambivalence creeps in. She worries about who get hurt when young living arrangements split up. She still believes in permanence. "If they just live together, they're only fooling themselves..." The 60 years between Mrs. Durham and today's young woman is marked by a very large difference of opinion on divorce. In Mrs. Durham's day, a woman stood only a 15 percent chance of divorcing or being divorced. And even then it was largely a phenomenon of the upper classes. The poor could not afford divorce. Divorce also carried a painful stigma. It could ruin a man's career, and it was often the end of a woman's hope of happiness. "The norm of the turn of the century was the double standard," Dr. Fullerton explains, "permitting men to remarry where women did not, and permitting a successful man, if he were discreet, to have affairs..." That changed in mother's day, although the divorce rate rose marginally to one in five marriages, a notion of what was to come. If the Depression was the watershed for grandmother's life, World War II was the watershed for mother. In only one generation, life changed greatly, but in ways not easily measurable at the time. Mother's ^chances of surviving| childbirth were 18 times better than the woman who bore her. Further, there was only one chance in 35 her newborn would perish. In mother's day the labor force had increased to 67 million, and unemployment was very low. With the men off to war, about one-third of the women worked. In the postwar recovery, mother inherited the dream themes of her own mother. But oddly, men still did the singing-from "Just Molly and me, and baby makes three, we're happy in my blue heaven," to "Someday we'll build a little home for two, or three or four or more, in loveland, for me and my gal." It all looked so idyllic. But other great changes were afoot. This statistical woman, bearing children in the 1940's and '50's was more mobile than her mother. Only 70 percent of her number remained in the state where they were born. The nation was flux, yet most people still lived in family settings. Family and togetherness. If there were catchwords for this generation, they would describe it best. "Twenty years ago most American women started their child-bearing at 19 and they had their last child before they were 30," explains Dr. Fullerton. Having children, fulfilling domestic dreams born of foxholes, long absences, five years out of the nation's life, was both a national and personal priority. "Mothers, born of Depression mothers, were very often only children," Dr. Fullerton adds. "They had the feeling that while they grew up alone, they wanted their children to have the companionship of brothers and sisters." But those dreams were not transferable. The very trend from small families to large families was to have its contrary reverberations when the baby-boom children grew up. There were also other seeds planted by mother's generation. The stigma against divorce lessened. Children became the focus of much of the nation's life. Dr. Spock ruled the land with a lenient hand. Mothers gave their children affluence and personal freedom, not always with the constraints that they themselves grew up with. Working mothers were no longer considered unusual. World War II did that. Nancy Fields is 50 and lives in Kansas. The path was clear when she came of age: "We knew we'd get married and our husband would bring home the paycheck. When a young man graduated from college he knew a job would be waiting. I never really thought of learning a marketable skill. My parents thought. I should be a well-rounded person, which would help in any husbands climb up any ladder.'' She sees today's young as "book- smart but not world-wise. There's a great inability among youth to see the long range. They postpone making decisions. The idea is 'if I A redefinition of 'The best educated, female in By JOHN BARBOUR AP Newsfeataie Writer Today's young American woman, in her 20s and 30s, her child-bearing years, is redefining just what it means to be a woman. She is, of course, the best educated, the healthiest, the most socially powerful female in American history. Thirty-three million strong, she is also the most active lobby of America's largest majority-women. More than any of her predecessors, she is free to choose the goals of her life-marriage, children, career-and the timing, the depth of fidelity to each. But all of that freedom-and some consider it less freedom than mandate-costs in deep and personal ways. No one woman can speak for all women, but through a series of interviews with experts and young women at this stage in life, strong themes emerge. And with the average educational level reaching into the college years, the freedom to choose tends to minimize the differences in social and economic levels. A special demographic study of three generations of American women—commissioned by The Associated Press-charts just how much things have changed from grandmother's day to this demanding new world today's young woman has inherited. Most things are "up" in her life. She has something better than a high school education, an advance of more than four years, 15 more than grandmother. If she becomes pregnant, she has only a one in 7,000 chance of dying in childbirth; her grandmother had one chance in 205. Her newborn has only one chance in 70 Of dying at birth, compared to one in 20 in grandmother's time. These are not random statistics. They reflect and influence the way she lives, the way she decides who and what she will be. She is marrying later, postponing babies. -Sometimes postponing marriage to the point of not marrying at all. There is another statistic in her life. A young woman in her 20s, marrying today, has a 40 percent chance of divorcing or being divorced. All of which diminishes the urgency of marriage. These young women, themselves the children of the baby boom, with the greatest numerical potential of producing children in American history, have produced the lowest fertility rate in that history—only 1.8 births per woman, less even than the 2.2 children produced by her Depression-fatigued grandmother. Aided and abetted by the Equal Employment Opportunity law, she is a sought-after member of the labor force, and she is advanced in positions of responsibility much faster than her grandmother could dream of. With 97.5 million workers, women constitute 41 percent of the labor force, and 61 percent of those are women in their childbearing years. More than half of the women with young children work. All of these forces conspire to change the lighting on womanhood, the concept of what a woman is—in male and female eyes. "Any period of rapid social change results in considerable confusion and distress on the part of people who are used to having rules set out for them," says Dr. Marjorie Hershey of Indiana University, who instructs women on new female roles. "It's very scary. Yet I also appreciate the feelings of many older women caught in between..." Today's women face a far different world than did the young women of only 20 years ago, says Dr. Matina Horner, president of Radcliffe College. "With that comes considerably more stress and conflict... You find many more young women today knowing they must have a career, and searching for something that would be satisfying and fulfilling." That means more than just a job as a way-station on the road to marriage. In some cases it means a job that carries the same emotional weight as marriage. "The young women today that I talk with want it all," says Dr. Margaret Huyek, a psychologist studying women at Illinois Institute of Technology. "They do not want so much to renounce what their mothers did. They want to add what their fathers did. They really have the sense that they don't have to choose between the two. Somehow they can do everything, and do it all between the ages of 20 and 40.". But can they?

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

The Western Carolinian is Western Carolina University's student-run newspaper. The paper was published as the Cullowhee Yodel from 1924 to 1931 before changing its name to The Western Carolinian in 1933.

-