Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2683)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (15)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

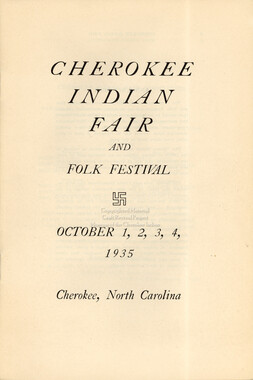

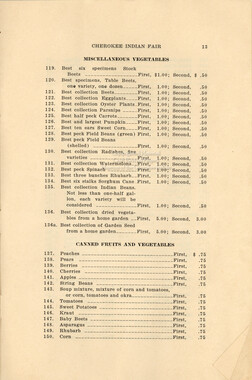

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (1)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (65)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (12)

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association (0)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (0)

- Berry, Walter (0)

- Brasstown Carvers (0)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (0)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (0)

- Champion Fibre Company (0)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Crowe, Amanda (0)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (0)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (0)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (0)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (0)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (0)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (0)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (0)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (0)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (0)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (0)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (0)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (0)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (0)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (0)

- North Carolina Park Commission (0)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (0)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (0)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (0)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (0)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (0)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (0)

- Stearns, I. K. (0)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (0)

- USFS (0)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (0)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (0)

- Western Carolina College (0)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (0)

- Western Carolina University (0)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (0)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (0)

- Williams, Isadora (0)

- 1800s (2)

- 1890s (6)

- 1900s (7)

- 1910s (1)

- 1920s (3)

- 1930s (13)

- 1940s (37)

- 1950s (12)

- 1960s (7)

- 1970s (38)

- 1980s (11)

- 1990s (2)

- 2000s (3)

- 2010s (38)

- 1600s (0)

- 1700s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1860s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 2020s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (256)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (2)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (1)

- Qualla Boundary (285)

- Asheville (N.C.) (0)

- Avery County (N.C.) (0)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (0)

- Clay County (N.C.) (0)

- Graham County (N.C.) (0)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (0)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (0)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Macon County (N.C.) (0)

- Madison County (N.C.) (0)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (0)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (0)

- Polk County (N.C.) (0)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (0)

- Swain County (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (0)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (0)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (3)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (3)

- Interviews (12)

- Newsletters (1)

- Photographs (208)

- Poetry (2)

- Publications (documents) (46)

- Sound Recordings (22)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (12)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Manuscripts (documents) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Personal Narratives (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Transcripts (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Horace Kephart Collection (1)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (0)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- Artisans (125)

- Cherokee art (18)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (27)

- Cherokee women (140)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (1)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (1)

- Storytelling (5)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (1)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (14)

- African Americans (0)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Education (0)

- Floods (0)

- Folk music (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Hunting (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- Mines and mineral resources (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- School integration -- Southern States (0)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- Slavery (0)

- Sports (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- World War, 1939-1945 (0)

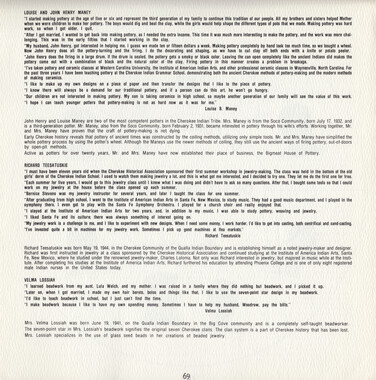

Tom Belt: Cherokee Language Teacher

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 1 START OF TOM BELT INTERVIEW David Brewin: We’re sitting here this morning with Tom Belt and we’re going to be talking about language and how important that is for any kind of for your tribal traditions and everything. Tell me a little bit about yourself, did you always speak Cherokee? Tom Belt: I grew up in a household that spoke Cherokee, Cherokee as a first language. We, my parents could speak English, but they only spoke English when they had to. We, I can’t remember a time when we didn’t speak Cherokee continuously in the home from one to another. My parents were both full bloods. My father was born in 1901 and I was born in 1951 which of course makes him 51 years old when I was born. My mother was 10 years younger, but having been born in that time in 1901 in Oklahoma it was 7 years, or 6 years before Oklahoma statehood so my father was actually born 6 years before Oklahoma was a state. In fact he was born in the old Cherokee Nation. Was a citizen of the Cherokee Nation. So both of my parents came from a time in which Cherokee, the integrity of the culture and the language of Cherokees was pretty much intact. Times were changing but to a great degree much of what had been Cherokee culture after removal was still intact even up until that day. In fact was pretty much intact all the way up til 1950’s, 60’s. So coming into that generation of in the 1950’s and growing up in the 1960’s, of course we of that generation most of us could speak Cherokee, most of us had been raised in those kinds of homes where Cherokee was the first language. I didn’t really learn Cherokee until I started public school. Of course we can’t remember those kinds of things clearly, but it seemed as though at some point or another that became, my knowledge of English became clearer and clearer. Probably around 4th grade or something like that. DB: Was Cherokee part of your school, were you allowed to speak Cherokee in school? TB: I grew up I mean, okay, I’m assuming you’re going to edit this is it alright to start, back up. DB: Oh yeah. TB: I began school in Muscogee, Oklahoma. My parents and my family lived in Muscogee about 1957 and stayed in Muscogee, Oklahoma for about 8 years. We moved out to my father’s on my father’s property out north of Tahlequah, Oklahoma, which is about from Muscogee it’s about 40 miles, 20 miles north of Tahlequah. But growing up in Muscogee and coming into school age that at the age of 6 or 7 the schools there were public school and there wasn’t any component or time allowed for language learning in those days. We were too busy learning English as all kids in public schools in this country do. But it wasn’t this or out. And in fact as I recall by the time I got into the 4th, 5th and 6th grade the school actually encouraged me to participate of certain kind of activities, such as giving an opening prayer. Maybe even in certain kinds of programs that they would have they would encourage me to maybe tell a Cherokee story and tell it in Cherokee. And in their own way they were I suppose very enthralled by the idea that they had a Native American child in their school system that could also speak their own Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 2 language, but they really had no way of using that for any… I don’t think they really had a way of knowing how to use that for educational purposes or anything like that. It was more like a novelty if you had anybody in your group that speaks another language sometimes you ask them to say things or give names for stuff. And that’s all that really [know to do]. It was encouraged as part of their showcasing that they had a child that could speak another language. But it wasn’t something that they tried to facilitate. Or… it was just clearly a novelty. DB: When did you come to the realization that this is a really important tradition to keep going? TB: After I graduated from high school. And up until I graduated from high school, as I said in those years there were… the culture and the language where I come from in those communities, in some 36 communities in Northeastern Oklahoma that comprise what is the old boundaries of the Cherokee Nation. In 36 communities across 14 counties, the level of language use, the level of Cherokee language use was still high. A lot of people still lived within cultural boundaries. By that I mean that they pretty much were traditional Cherokee people. They lived that way, they thought way, they interacted with one another in that manner. So the idea of their being any kind of necessary thought to maintaining the language and culture wasn’t really a part of what I thought about and of course during those adolescent and post adolescent, I mean post adolescent years also there were so many other things to be involved with that you don’t give much about those kind of intrinsic social cultural consideration. You really don’t think about things like that much. It wasn’t until after high school, and it wasn’t until really I guess about the age of 19 or 20 when you reach that, when the cognitive part of your mind begins to kick in. But I began to think about certain kinds of things. Certain kinds of things that pertain to our identity. To who I was, and immediately then I began to look around me to see what I had that validated all of those things. And it wasn’t until then that I began to really understand the importance of culture. And I also began to understand that it was depleting, that it was diminishing. That it wasn’t exactly like I thought in that there was always going to be Cherokee people, that there are always going to be Cherokee people and was always going to be a language. I began to look around and see that what was happening was… a change was happening and people were beginning to lose those values and people were beginning to change. And not be as intrinsically Cherokee as they had once been. And whether that was due to that age period which becomes… comes into those kinds of things as you begin to mature, or whether or not it was part of what we called the 60’s. During that consciousness raising era. But I never, but either way it did begin to occur to me at that time. And I began to see that those things that I had been taught, those ways that I had been taught to look at the world, the way in which I had been taught to view the world, wasn’t exactly what a lot of my relatives, a lot of people my age were thinking about or talking about or were doing. They were involved and we were all becoming more and more involved in things that only pertain to us. The need for money, the need to be accepted in a larger societies than in…the need to be accepted in larger societies more societies than those that we had been raised in. The never ending thought that there was someplace else to go to, somewhere further away. And even to the extent that some people were saying we have to change, we have to become something else, we have to Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 3 start doing things in a different way. And as I began to realize that that is how people were thinking and that’s what was happening back home in Cherokee [inaudible] I saw that what we were looking at, what people were looking at and trying to achieve wasn’t valuable as what we’d been taught as a way that we had been taught to look at the world. And so much of the knowledge about things, the knowledge of interpersonal relationships, relationships, kinfolk [systems], the considerations for the environment that we lived in, our connection with that. In other words the time we spent together fishing the times we spent together doing things that people didn’t want to do anymore. Like for example there were always family gatherings going on. If it wasn’t family gatherings, then we had community gatherings. If it wasn't that it was just 4 or 5 people that got together along the way with their families and decided to go to the river and catch fish, or gig fish, spear fish as we called it, I mean gig fish as we call it back home, have a fish fry on the banks of the lake, or the banks of the river or creek. Getting together to go to hunt crawdads. The seasonal activities that people participated in together as a group. All of these things were beginning to go away and weren’t happening as much. All of these things that had been so much a part of our lives, so much a part of the way in which we did things, were coming to an end. And it was being replaced by people just simply going about their own lives and not having, having as little contact as possible with people. Just the every day contact. The meeting with people, going to and from work. The continued contact with one’s family of course was always a part, but that’s all, it just began to be interpersonal relationships with your own immediate family. And what I saw was, there wasn’t as much happiness anymore. There wasn’t as much tribalism, connections were being lost. The way in which our people used to visit one another. The way in which our people used to go and visit and maybe spend the night with someone, even thought they just lived a half mile away. People getting together as I said doing seasonal things. Picking berries, being in the woods doing things. All of that was beginning to slowly fade away. And it was being replaced by very, very let me think of the right word, it was it was being replaced by some kind of exclusive an exclusiveness. Just you and one person maybe just with you and your family. But the rest of your time was being spent going about the business of whatever it was that you thought was important to your life, work, not paying attention to any other thing. And then also with it I began to notice that the younger children, the one’s who were, as I was 19, the ones who were 10, the ones who were 15 didn’t speak much Cherokee anymore. It was getting rarer and rarer, and finally in the middle 70’s sometime about the middle 70’s I began to realize that all of the young children, all of the young children when you attended a Cherokee event, church or ceremonial most of the children didn’t speak Cherokee anymore. And in a very short, it all occurred in a very short period of time. Just 5 years before, just 7 years before that, 8 years before that you could go to one of those activities and virtually all the children spoke Cherokee running around chasing each other. And so I was beginning to see by the time I was 25 I clearly began to see the loss of everything that was intrinsically Cherokee. And I began to, then I began to understand that one of the most important way, one of the ways it was more conducive to loss of culture than any other thing in this society, whether it was media, the economy or the political climate, what was doing more damage to our culture than anything else was the loss of language. I’ve said many times that language is simply the way in which a people interpret the world, any people, anywhere on the face of the earth. Language is the way in which all things interpret the world, it’s Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 4 the way birds interpret the world. It’s the way that any living thing that communicates with one of its own kind interprets the situation currently about them. And also in human beings is the way in which we access the past. Thereby creating, thereby creating a way in which we can look at how we are going to do things in the future. That’s all language really is. But it is essential and the very most important part of maintaining a culture, any culture than any kind of artifact, or any other thing could ever produce. In other words baskets, pottery, artisan work, is a skill, a skill that’s acquired by memory and its meaning is whatever the creator of that wants it to be. It doesn’t carry on… a basket doesn’t carry on things like child rearing practices. It doesn’t carry on the vast knowledge of biodiversity with it. It doesn’t carry on a connection with people in so much as it only connects people who recognize that artifact or that thing. Language does all of those things. Language puts into perspective, where you’ve been, how many of you have been there and a sense of how long ago it was, the time it was. And gives you a perspective on how to look at things in order to adjudicate them in order to analyze them to put to the best use the way in which you’re going to continue to do stuff. If you can’t interpret things that way, then you have to borrow somebody else’s interpretation. And when you borrow someone else’s interpretation, then you become like them. You are no longer unique because you don’t have a unique way of interpreting the world. You simply begin to look at the world through the eyes and with the ears of that language that you communicate with. Things that are not talked about in Cherokee, things that are not described that way intrinsically are only an interpretations from another culture. People try very, very hard to interpret those things in English, but anybody will tell you that if you talk about those things in Cherokee it takes on a whole different meaning. The very essence of the word sometimes carry another kind of interpretation. Encoded in a language are all the things that ever happened to that people all the ways of looking at the world and sometimes teaches us how we [inaudible] to look at the world . No I’ll take that back. You can edit that out, and also teaches us then how we ought to look at the world. And therefore gives us a way to be something. It gives us a sense and a paradigm to continue on a culture that has been around for millennia upon millennia. To maybe thing about things that’s never been thought that isn't as accepted. What is considered folklore and what is considered wonderful superstitions of a culture may in fact be a kind of a science that that predominate language , the culture that produces a predominate language hasn’t quite wrapped it’s mind around yet. After all these people have millennia upon millennia to hone their understanding of the world around them. And the way in which that’s discussed is all encoded in the language. And about the age of 25 I began to see a great loss of not just a language and certain kinds of artifacts, but a whole way of life, and a whole way of looking at the world. Maybe an important factor in the survival of all of us. And it wasn’t too long after that that I began to understand the importance of all languages. And all cultures, the great myriad of cultures the great diversity of cultures of the word are in fact the great… are in fact the treasure of the world. It’s garnered information. It’s garnered wisdom, its collective wisdom from the very beginnings of man. And the loss of one of those languages is key, may be a key factor in understanding a part of the world, it may be that might be the key to solving a lot of problems. But certainly it substantiates the right of a people to exist on the face of the earth. Language I believe is one of the many important factors in establishing the great birthright of all human beings. And clearly has something to do with the purpose of human beings and Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 5 the understanding of this world, of this creation of this particular environment that we live in and without it I think we are diminished. DB: What do you think is the biggest difference between English and Cherokee? TB: Well English is a language of nouns. The identification of things. Most indigenous languages including Cherokee [inaudible] are languages built of verbs, built of a kinetic understanding of how things work, as opposed to just what things are. We… we have… there are there are some noted scholars that have worked on the Cherokee language and if their understanding if the linguistic rules apply in such a way so they think they do and if in fact words do play that way, they say that a verb in the Cherokee language could be gosh, I’m losing my thought pattern now. Okay they say that a verb in Cherokee can be conjugated 20,000 times, one word. For example dancing, or walking, if you can consider those words being conjugated that one separate that one single worked being conjugated 20,000 different ways, you begin to understand that they way in which things are analyzed the way a meaning of walking the meaning of dancing is far, far more profound and far, far more varied than we can even begin to put into words in [inaudible] English. With the use of one word, at some point along that line of conjugation, somewhere along around the ten thousandth word you understand that dancing is some kind of intrinsic part of physical, social, psychological, spiritual it’s and it’s part, it has all those components with it. Because certainly if there is a word to describe those things, then it means that the people who say those words, look at it that way. And it becomes very important. If I tell you for example we are going to go eat shortly. Unless I’m more clear about it, you really do not know who I’m talking about when I say we. It could be you and I, it could be myself and some other people, it could be me and someone else. It could be all of us and not you. It could be you and me and some other people and nobody else. It could be all those things, you really do not have a clear idea of who we are. But in Cherokee I say we are going to go eat shortly, you may not know the names of everyone, or you may not know exactly who I’m talking about but you know which group I’m talking about and who I’m talking about in the way in which I say that. I can say we’re going to go eat and mean you and I. I can say we’re going to go eat and mean me and a whole bunch of other people and not you. I can say and you will understand it. And I can use a word, using that same word I can conjugate it and to make it mean that you and I and no one else, you and me and someone else and nobody else. Me and a whole bunch of other people and not you. On and on and on. So that in just the exclamation of that one word, you have a clear idea of who I’m talking about. So it brings to mind that in Cherokee, it appears as though the language was honed to make it precise, absolutely precise. And then on top of which there are ways to tell you to let you know in a way in which I use that word whether or not that will happen quickly, or that will happen maybe later on, or maybe 28 days from now. All of that in one word depending on how I use that. Depending on how I turn it, depending on how I use tonal expression all of that will give you that information. And with English then it becomes more black and white and as you can tell by that short presentation begins to become a long drawn out explanatory thing. Clearly Cherokee was meant to get to the point as quickly as possible in the most significant way and in the most integral way to convey not only just the thought but to convey information that would help you in deciding how you’re going to react to that. And in fact we have, we Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 6 have… we have a way of conjugating words in our language we as I said that can talk about I can behave if I tell you that I did something then that, in the word that I use you would be able to discern whether or not that was just in the immediate past, or whether that was sometimes back, or whether or not it was a longer time back. And even to the case… and I could even change it around to give you the impression that it might happen, that I might have done it and that I might not have done it. Used more clearly in describing what somebody else did for example let’s call it a report in a sense, in that I can tell you that so and so did something and that was immediate or sometime in the past. And then I can also use a term describing the same action that tells you that it’s that it tells you that I do not have personal, I do not have personal information, I haven’t the personal knowledge of that. In other words if I tell you you were dancing then I might use the word [Cherokee word] and that means you were dancing. [Cherokee word] You were dancing around. [Cherokee word – all three are very similar in sound] All from the same word, that means you were dancing but I have no personal knowledge of it, it might be just something somebody told me. And so it’s just, that’s just 4 conjugation of the 20,000 ways. In other words the language is very precise. And the great responsibility of that language then was in the way in which you used it and the words in which you chose. And it helped people to decide many things. It helped people to decide what they were going to do about the act that you just referred to or how they were going to react to what you had just reported or what you just said. But it also indicated who you were. And what you knew. And whether or not simple things like whether or not you could be trusted or not. Whether or not you actually had knowledge of these things or whether or not you had the kind of integrity to be talking of these kinds of things. All in a simple verbal delivery. So you can see what we say, or what we mean by the statement that language is in fact the core part of our culture that indicates almost virtually everything. And without it then we have to borrow somebody else’s way. There’s a statement and I keep forgetting who it was that said it because I’m just going to have to look it up, but the statement goes, English doesn’t follow other languages, excuse me English doesn’t borrow from other languages, it follows other languages down dark ally ways, hits them over the head and goes through their pockets for spare vocabulary. A language born of that kind of quality or a language born and honed for the purposes simply of presenting that isn’t quite as old and isn’t quite as to me doesn’t have as much integrity as a language that’s been honed over millennia to use explicit concepts on its own. To explain explicit concepts within the boundaries of its own language. And I think that in the past, I think the world is becoming aware of this. The days of thinking that cultures and languages are subordinate to dominate culture I think is slowly fading away as time goes along. With the instituting for example, the United Nations and having interpreters for every language that’s spoken there clearly says that language is important and things have to be said in a certain kind of way. It doesn’t call for all nations to assemble and speak one language. I think that as time goes along if there is enough time for the human species on the face of this earth that the importance of language will become more and more apparent and will be taken into consideration, in all considerations about life in general. DB: When you were talking about the way the language is used and everything and the variations and whatnot, is the syllabary able to accurately portray some of these different conjugations and everything? Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 7 TB: The instituting of a syllabary or written way of representing our language by Sequoyah was never intended to be the actual way in which we converse. The syllabary was never intended to interpret the language or to be used as a tool in order to access the language for understanding. In other words, Sequoyah invented the syllabary specifically for people who spoke Cherokee. There’s no grammar. In the beginning I’m not even for sure they used a period at the end of sentences, I think they just drew a line. It is a representation of the sounds of our language and only those who can, who have knowledge of the sounds of our language in other words, only speakers can use the syllabary to any kind of degree that would be useful. Anyone can learn the syllabary, I’ve met many non-Cherokees, non speakers, people who really haven’t been around Cherokee people much or hardly any in their lifetime who know the syllabary completely. And if you can produce the sound, they can write the symbol for it, but they actually have no knowledge of what that means, it’s just sound. Learning the syllabary is not that hard of a thing to do if you just resolve it to [rote] memory. The syllabary then was only important to those people who spoke Cherokee and those people who could use it correctly. It was on a on a surface level, the syllabary allowed us to record things, to write about certain kind of things, and maybe even to pass around the information. That could be utilized in a way that might be able, that might be conducive to finding out what kinds of words people use a 100 years ago. If we find manuscripts if we find writings from that time period it’s very, very helpful in finding out the language modem that was used. The way in which people spoke. Dialectical tones for example. All these things, words not in use. But beyond that it always has been and will always continue to be simply a way that one may pass along the information currently that may be of some importance to what’s going on now. But at the same time now it has become a great cultural property and it was a way that you can pass along information if you so desire. And so very quickly too certain kinds of writing became very sacred. And only used in certain kinds of, you know used for certain kinds of things. And of course then that means that that kind of use of the syllabary isn’t opened to the public isn’t opened to everyone, so once again it is in fact away of a way of actually accessing verbal language. So it leads back to the same thing. It was never a, it was never… well to be honest with you, writing in Cherokee has never achieved sacred level. They only interpret certain things that were sacred, but the writings themselves were not. Because it took someone who also could interpret that. But the great achievement of the syllabary was that we could access information from one another, we could pass along information to one another, and certainly assisted the way in which things were thought about and kept part of that alive too. But it was never intended as a tool to learn how to use the language or a way of getting into the minds of [inaudible] because the things that were written were never really truly about the way Cherokee people thought anyway. They were just current information or the interpretation of things, like for example the interpretation of the New Testament is just a transliteration of the New Testament itself. It’s usage in linguistic anthropology is in the words themselves to find out if there were words that, in linguistic anthropological term the great importance of those transliterations and those translations and stuff is simply in accessing words that we don’t use anymore. Because we could certainly just read the New Testament in English or in another language and get everything that that said too. So it wasn’t all that important. Only in the way in which it Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 8 was important to the concept of Christianity. But not so much important to the idea of Cherokee culture. So the syllabary has been a wonderful tool in making certain kinds of literacy possible, but it hasn’t been as much of what people think it has been. But it is certainly a great tool. DB: What is the state of Cherokee language today? TB: I believe the Cherokee in linguistic terms has been categorized as a being morbid, of being in a morbid state, which basically means that it is dying. Among the 14,000 enrolled members of the eastern band less than 290 speak. In the 14 counties of northeastern Okalahoma that comprise both that is the Cherokee Nation and the United Kituwha band, among those two groups of people there are estimates of there being 6,000 speakers left. The numbers of Cherokees there as far as enrolment or members of those tribes and stuff is extremely arbitrary. Depending on who is doing the analysis of it and stuff. It is said that there are 250,000 members of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. I’m not for sure if there ever has been that many Cherokee. I’m certain there are 250,000 people who claim to be Cherokee, but I would put the number more about 30,000, 35,000 maybe Cherokees and 6,000 or so that speak it. So proportionately in North Carolina and in Oklahoma I think the language loss is at about the same level. With the instituting of immersion schools both here and there we now have the number of those enrolled in those immersion schools as the only number of people who are replacing loss of speakers every day. So they have at least 30 young children here that are learning the language. I’m not for sure exact the enrollment of the immersion school in Oklahoma, but it is a little bit higher. Therein then technically would be would lie the members in those numbers are then are the only wait a minute, in those numbers are the only hope for the future of Cherokee language. In those 25, 30 students we have here and how every many in those language programs because aside from those children that might be learning in their home which is very, very few there and almost non-existent here, those are the only ones. And so if there is to be a rebirth of the language if the language is to be revitalized, if the language is to come into use again, we’re looking at many years of language learning and with methods not yet put into place. In other words there’s going to have to be new ways of teaching it. That we have may not even thought of yet. But certainly the most important concept at the bottom of it is always going to be whether people feel as though it is still needed and that is an important factor. And I believe that both in Oklahoma and here the belief and the concept and the idea that the language is important is gaining foothold. By people who are some 2, 3, 4, generations removed from it. They are beginning to understand that this is the important thing that all may be lost. Culturally speaking, identity speaking if the language doesn’t continue. So little by little, day by day, little steps are taken are being taken to ensure that the language survives and the tribal [inaudible] themselves are taking it to hand as much as they possibly can at this point. But certainly that’s going to have to be the way in which it occurs. It’s going to have to be a community concept. As much as it’s always been among Cherokee people. Ideas that come from the outside never work, have never worked. And unless it comes from the Indian community itself and so ideas that are going to work, things that are going to happen have to come from within the community itself. So every language has the idea of maintaining a language, the foothold of language learning has in our Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 9 community getting stronger and stronger now how that plays out now that pans out we can only wait and see. But we can cross our fingers and we can hope it will turn out for the best somewhere down the line. Language will become more important component of our daily lives. It’s the only way in which our culture will survive. DB: Anything else you’d like to add? TB: I can’t think of anything else. DB: I’ve got a question that I’ve always wondered you know. You read things for the 1880’s 1890’s translations of what our leaders said in response to probably our trying to steal their lands and whatnot and treaties and everything seem so flowery and I always used to think that was some kind of a Victorian thing. From what you’re saying it’s a very descriptive language. TB: There’s an account of I just heard somebody one of my collogues was talking about a journal that had been written by someone, that they’d read I’m not sure where it came from or who it was, but in describing having attended a council meeting at Chota and one of the head men getting up to speak in council in Cherokee. And of course he wrote that he didn’t understand a word that he said and he spoke for almost an hour. But he said the way in which he spoke, and the way in which he presented the ideas that he was talking about were done in such a manner that even I without knowing the language understood clearly that this was an important thing and gave all due respect to the speaker for that whole period without knowing what he was saying. So that the presentation of it and the way that he spoke, the say that this man spoke clearly indicated that his knowledge, his mastery of the language was such that when they spoke they commanded great respect and carried themselves and presented it in such a way that bespeaks of great orators throughout history and even in Europe as far back that’s the idea that this man got from that. And of course was absolutely correct. They had great command of the language. Language was an important thing. Language has always been an important thing. If you were going to a Cherokee town probably in the 1700’s and the 1600’s in any Cherokee town in what is the Cherokee domain the historical Cherokee domain the Cherokee Nation or the people, probably in that town you would find a great diversity of language. In other words, somebody there spoke Shawnee, somebody spoke Creek, someone spoke Catawba, there was there are people in those towns and the language of many nations, of many tribes were present and in those towns. Probably no matter how small the town was. In accessing information, needed information about things going on currently, from all over the southeast everyone had to be up on everything and the only way that you could understand and be up on everything is to understand what people are saying and what they are talking about and the only way you can do that is to understand what they’re talking about in their own languages. I think they clearly understood that a long time ago. So if you came into Cherokee county you would understand that they were probably multilingual there. The common language was of course Cherokee, the way things were done were Cherokee, but if you had to find someone, if you came in from a different tribe and had to have someone interpret for you, it wouldn’t be hard to find somebody. It says that they understood the importance of linguistic diversity. The Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 10 importance of not having everyone speak Cherokee or that you had to understand everyone, because in it you were giving respect to everyone’s nature and everyone’s interpretation of the world. And it would help you to understand yours better. We were never against information, we were never against wisdom from anybody. [laugh] But in order to access that you have to understand how they look at it, their interpretation. After all it is their knowledge it is their wisdom. And the only way to know those kinds of things, or the only way to appreciate those kind of things is to understand how they look at it. Otherwise you’re just looking at it from your own perspective and you’ve lost it. So even in that period of time down into all the way until… until now, I think most Cherokee those who speak Cherokee, the speakers of our tribes I think if you were to talk to them they would also talk about the importance of everyone’s languages and I think they would... so I think that they still understand that and it is still a part of our culture to appreciate all languages, to appreciate them. But not necessarily use them to interpret what your world is about but just to learn from it. END OF TOM BELT INTERVIEW START OF TONYA CARROLL AND TOM BELT INTERVIEW David Brewin: What we’ve been doing here, about learning from these people learning from your elders. Tonya Carroll: I’m a little confused about what I’m supposed to talk about, are we talking about the interviews we’ve been doing. Or what I know about the language. DB: I just wanted to know what you thought about the traditions of being Cherokee and passing, because you and I have done a lot of traditions and actually I guess I’m asking you has it impacted you in any way? TC: What we’ve been doing? DB: mhmm TC: Well I’ve grown up in Cherokee and know all of the people that we interviewed and a lot more that carry on the traditions, so what they’ve been saying in these interviews I’ve heard all my life. So being able to document it and have it recorded for future generations is important but it hasn’t been necessary for me just because I’ve been around all of them before and the importance of keeping the traditions alive has always been expressed to me. DB: Well then how long have you known Tom Belt? Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 11 TC: I’ve known Mr. Belt since I was probably about 7 or 8. I attended Cherokee elementary school as a child and my first Cherokee language teacher was Marie Junaluska and she left the school and Myrtle Driver and Mr. Belt came in as our new Cherokee language teachers. And he’s just always been a teacher to me since I was 7 and I even took Cherokee language courses with him and college student at Western Carolina University. DB: When did you come to Cherokee Tom? When did you come to Cherokee? Tom Belt: I came to Cherokee in 1991, June of 1991. I came to visit an old friend of mine a person I had gone to school with. I had gone to school at the University of Colorado with some 20 years before. And I came to visit and I had a round trip ticket and never used the other end of it and just stayed and have been here ever since. Been now I guess 19 years. I taught at the elementary school for 7 years and then did a brief and then I worked at the local [unity] center for another 7 years and then went back to teaching at Western Carolina University about 3 years ago. Why do you think, Tonya then, I mean…luckily he’s going to edit all of this. So you say you grew up knowing the people and knowing about these things, but your understanding of these things had to come from someplace else. What’s the way, what are the ways in which you can understand about… What are the ways that you came to understanding about Cherokee culture and what Cherokee culture means to you [inaudible]? TC: As long as I can remember, every Sunday I would go with my family, with my parents up to the Big Cove community that’s where my dad’s family is from. And we would eat a big Sunday that my great-great grandmother would cook. Her name was Ella Pheasant Sequoyah, and we would go up there and the whole family would come up and she cooked bean bread and fried chicken and greens or cabbage, whatever from out of her garden. And she had chickens and she’d kill the chickens herself and we would all go up there to eat and she prepared the whole meal for I’d say about 10 to 15 people every Sunday on her woodstove in her she had two bedrooms and a small living room and the kitchen. And we’d all go up there and I would play in the creek with my cousins and they would all sit around and she could speak Cherokee and so I could hear a little bit from her. And that’s just something I can remember we would do every Sunday and that kind of stressed the importance of family to me. And on my mom’s side of the family her father’s Cherokee and he always stressed the importance of language to her. He’s not a fluent Cherokee speaker, but he is a gospel singer and his gospel singing group would sing a lot of their songs in Cherokee and she said every night when they ate dinner that he would make them say some of the words in Cherokee before they were able to get their food. So I guess it was always just instilled in my parents those important things. And in school I was always interested in taking the Cherokee language classes and a lot of the times I would win the Cherokee language award at the end of the year. There was a traditional dance group that I was a participant in and we would maybe travel sometimes Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 12 doing the different social dances, the bear dance. I guess it was just always around me and I was always part of it and I had fun doing that. I didn’t really realize that I was learning all the different things to do with the culture it was just every day things for me. And when I was 15 I got a job as a tour guide at the Oconaluftee Indian Village. And I had always wanted to work up there. We would take field trips from school and go up there and I just really loved it and loved being up there and I started working up there. And I quickly learned that it wasn’t just a job up there that you became a part of the family. And there was a lot of Cherokee elders up there that kind of took me and they would always bring me food and I just really liked going and visiting with them and sitting with them and just talking to them. And I liked to… none of my friends that are my age ever really acted like that and were interested in sitting with these older people and talking to them. And I don’t know why I found that interesting, I guess I’m just kind of have an old soul. I always enjoyed being around it and I always enjoyed learning about the language and I took the language classes and it’s just something that I was always interested in. And my family played a big role in encouraging me to learn more about these things. And now I went on to Western and got a minor in Cherokee studies and I’m working in Cherokee and still I’m around people that participate in traditions and culture and I love it. Tom Belt: So it seems as though then all things pertain to Cherokee, a great deal of things that pertain to Cherokee culture have always sort of kind of been around you and always kind of interacted with that. Something that you’ve always been around as you said. Tell me something tell me, and I’m not, and you can answer it any way that you want to, but eventually you have to get down to the heart of matters in [something] and the things we know about, our culture the things we do the people we know, [and stuff like that] [inaudible], but we don’t speak very much sometimes, or don’t have the opportunity to speak about what all that means to us. And to make that into a question might be that you might have… that could be answerable in the best possible way, I would ask you then, in all in of your lifetime, having been around it, and having participated in those kinds of things and doing those kinds of things, one would have to ask then, what made you want to do that, what is it that down at the core of it. What is it that it all means to you? I mean because people would ask well I can understand wanting good grades to get by in those classes I can understand you wanting to have a job locally, wanting to be a part of things in your own community, but beyond that, deeper than that for someone to have as much connection and kept that connection with things even to working with the job you have right now is indicative of your involvement in that. What is it to you, what do you think it is inside for you that or that you saw that is important enough that it becomes so much a part of your life? TC: Well it wasn’t until I guess about 3 or 4 years ago that I really started thinking about that. I guess when you’re around it so much you don’t really think about why, it’s just the way it is. But we had Bo Taylor come to our class, I don’t know if you remember when he talked and he asked up what does it mean to be Cherokee? And it just seems like a simple question and I should have had an answer for him right then, because I am Cherokee and I grew up here and it is important but I didn’t. I thought, what does it mean to be Cherokee and he wanted an answer right then and I probably rattled something off Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 13 about having a language and a culture that is different. But ever since then it comes to me sometimes and I really think about it, and it’s a feeling that I get whenever I’m around people that know the culture and know the language and it's really hard to describe, but it’s just like knowing that there’s a place that I can call home that I’m always comfortable, that most people know me, and they just accept me whether I do great things or do horrible things, they accept me for who I am. And we are unique and we are different, but it’s hard to explain to someone how we’re different or how that feelings different from someone else because it’s just a feeling of being comfortable and you can be yourself and just be happy with each other. And it sounds like everybody could have that, but I’ve just found, I went to the public high school, and I’ve been away from Cherokee and a lot of people don’t have that. They don’t have that community of people that look out for them and help them and have those special things that make them different, but they can all relate to one another. And I don’t know when or I can’t think when a time when I realized that or recognized that, like I said I don’t know why I’m interested in it, but when I go to the speakers meetings, or when I’m around people that are just talking, I just get this feeling and it just makes me happy that we can do this. Does that make sense? TB: The chief of the Cherokee Nation now Chad Smith is talking about the importance of language the importance of the Cherokee language and in a statement he said something to the effect of he’d never known a time when two Cherokee speakers got together or when any group of Cherokee speakers got together when they came into a room or they met each other on the street they almost, almost perfectly, almost every time that he could remember experiencing or seeing that they didn’t within a few minutes, within a few seconds begin to smile and laugh. And he said he’d come across many people speak many languages when they meet they didn’t always do that, they may have smiled and extended courtesies and such [in any other language] But it seemed like the Cherokee every time they met no matter what the situation was within seconds they would be laughter which indicates happiness. And he said it seemed impossible to think that a language that does that automatically would be something that people would want to lose. Language is not only brings with it all the things, but also induces happiness. A language that makes you feel happy. Is that the kind of feeling that you were just being around your own culture, is that what you’re saying, just being around it, just participating in it creates that kind of feeling? TC: It does, just being around people that can speak the language and hearing it, even if I don’t understand what they’re saying, they are so happy to be able to talk to one another and that makes me happy. When I would go to the speakers’ meetings, they just have such a good time. They are always laughing and cutting up and most of the time I don’t understand really every single word that they say, but it is just so happy, and they are so happy it makes you happy and then when I do understand something it I just get so excited that I actually understood and could get the joke. TB: Renissa Walker once said that she had a dream, the director of the program that facilitates the immersion school. Said she had a dream one night that she could speak that there and her mother were speaking in Cherokee and of course her mother is a fluent Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 14 speaker here, but she is not. And she said she in this dream she was they were carrying on a conversation and they were going about daily business, going about stuff and she could speak Cherokee with her mom. And she said when she woke up she of course realized that she couldn’t do that. And of course she said she immediately just burst into tears. In reality she wasn’t able to do that, unless she learned how to speak the language. One of the things that occurs to me, or one of the things that I know about you as a, whether or not you realize it at this point, or whether or not you’ve thought about it at this point, your connection, your activities, all of your efforts and the things that you’ve done to this point in relation to Cherokee culture in relation to your involvement with stuff, one could tell that you were going to do that even when you were 6 or 7 years old. One could tell. We knew that and we can see children when they are growing up and we can watch them and you’ve always had an interest in that and I’m sure that you never really understood why. But do you think that one could surmise by saying that maybe that’s what culture is, it’s not in being able to describe it, it’s not being able to put it into words, but just knowing that you are just a part it, it’s like the air that you breath, it’s just a part of who you are. And at some point we all do have to come to the point to where we have to think about how we put that into words. But what I’m telling you is that I think you’ve always been a part of it because you’ve always been intrinsically Cherokee even as a little girl. It’s always been a part of your life, you’ve always looked at it as if it is something that is a part of you. And you’ve always have always return home, in our thoughts in the way in which we validate ourselves, always remember who we are to remember what we’re supposed to be. And how important that that is. Because how important that is is in fact how important we are. And I think that’s what you’ve done in your lifetime, I think that you’ve always been a part of that. Why is it important to be that? To you. These are tough questions. Why is that important when you could very easily was out of here and go any place in this country and take on a life the has nothing to do with anything Native American and live the rest of your life that way. Why is it important that you are here, why is it important that you think this is home, why is it important the you be that? TC: There was time when I was in high school when I started thinking about where I wanted to go to college and what I wanted to do, it never was a matter of was I going to college, I was, it was where, what I was going to do and I thought, and I had the grades and everything to go a lot of different places and I made up my mind I was getting away and I was going as far as I could and I wanted to go to Brown up north and I don’t know why, that was just where I wanted to go. And I had my mind made up that’s where I was going and I was going to apply there and when it came down to it and I thought about it, I didn’t want to leave. And I wanted to stay here and I wanted to go somewhere where I could get an education in… that would help me come back to Cherokee and help the community and do good things for them. And I thought with my grades I could go on and get an education and be able to come back and have that education just to help the tribe and the community. And the only place that to offer anything in Cherokee history or culture is Western Carolina University and it was just a minor in Cherokee studies. And I thought that’s it, that’s where I’m going and that’s the only place I applied and luckily I got in, and made it. I didn't declare a major, I had no idea what I wanted my major to be, but I just knew that I wanted that Cherokee studies minor. And I chose nutrition, it came down to where I had to pick and so I just chose nutrition and took a semester of that and I Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 15 then just thought I didn’t want to do that and I ended up in history and I thought, I wanted to come back and work for the Renissa Walker’s program. It had been started and they were doing a lot of really good things in the community with the language and the culture and so I decided to go with history and took some classes in that, took a all of language classes, but the bottom line is I wanted to come back and I wanted to be here and work and help keep the culture and the language alive for our tribe. What was the question? TB: What does it mean to be that to you? I’m posing the same question that Bo Taylor posed to you, after all your consideration looking back what to you think it means to you, not general public, not in an academic sense, or a sociological sense, but just to you Tonya Carroll, what does it mean to you to be Cherokee, what does the concept of that mean to you? TC: Well first the reasons that I… aside from just having a genuine interest and learning about the culture and the language I said earlier growing up none of the people that were my age had that interest, none of them were learning anything from their families about those things. And somewhere along the line I just realized somebody needs to, we need to keep this alive and it’s important for people to die for, people have. And so I thought well, I could do it, I can learn. And that’s what I’ve been doing whenever somebody says well nobody had ever really offered to teach me, but when I worked at the Indian Village I would go around and I would say, to the people making beadwork, I would say can you show me how to do that. Or the people making baskets, and while they were teaching me how to make baskets a lot of them could speak Cherokee and so then I would say what is the word of river cane. And they really appreciated somebody just having that interest and wanting to learn from them. And it seems like somewhere along the line some of them feel like they’re not important anymore, or what they know and their knowledge is not important anymore because they don’t have a degree or that type of education and while that is important, their knowledge that they have is something that I never learned in my Cherokee study classes, is something I could only learn from them. It wasn’t written down anywhere or in any text books that I would read for my classes. I had to learn that from them, stuff that they knew and they learned from their parents and their grandparents and that’s when I thought I need this education from Western and I need to know how to talk and voice my opinion and write papers and be well spoken but I also need their experience and what these elder and what our tradition bearers know because if I don’t learn it from them, nobody is going to know. And I think that’s the most important part for me about being Cherokee. It’s not having my enrollment card that shows my degree of blood or telling people or having the benefits from it, it’s just being able to keep something alive that has been here forever that is special just to our group of people and if I have to be the one to learn that I’m willing to. And I don’t want the credit for it or to be in the front to say hey look what I know. I just want them to know that what they know is important and that there are people that are interested in learning from them. TB: And so they’ll come a time one of these days when you will have to explain to one of us, when you’ll have to explain to one of my grandchildren, or somebody’s grandchild or somebody’s child why they have to do that or why it is important, what are you going to tell them? Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 16 TC: I don’t know, I’m not really sure about that. I haven’t exactly come to terms with I’m going to be the one responsible for all that. But no one I always heard keeping the culture alive is important, learning the language is important, nobody ever had to make me want to, nobody ever had to say Tonya you have to come to Cherokee language class, you have to learn these words, I always just had that interest and had that want. And I see it in kids today, there’s children that I see and they have that want and they have that interest and I’m not really worried about having to explain to them why because they’ll know and they’ll have that feeling and you won’t have to tell them why. And I see those kids, the immersion, at the immersion school and they’re already learning at that young age and I think that’s really great what they are doing up there. And I don’t think we’ll have to worry about telling people. TB: In the case of you in the case of having to tell someone, if you had to what would you tell them? TC: Why they should? TB: Yeah, [what is this all about]? TC: Hmm TB: I heard from my grandmother when I was 17 years old I’m fairly certain no one ever asked my grandmother what she thought Cherokee was, why it was important, I’m sure she was never asked that. I’m sure she never had to explain that. The reason why is because people in those days were just that weren’t they, they were just Cherokee, everything that they knew, that you’ve said, everything that they looked at it was just who they were, they never had to explain it, it’s just who they were. But she told us one day, just a few years before she passed away, someone was asked, someone was talking about don’t you wish things were like they used to be along time ago when you were growing up. And she you could tell she was thinking about it for awhile. And she said the way things were when I was growing up are still here, it’s still the same [road], it’s just that people don’t do certain things anymore like they used to, but it’s all still here. All of the knowledge, all of the ways all of the reasons why people do things like they used to at one time or another, they’re all still here. Because people don’t change, people don’t change unless they want to and when they want to and they become something else that’s the only time that everybody becomes different, that’s when the world changes. And she said I don’t think the world is supposed to change like that. She said everyone of you all [who are sitting here or anything that ever happened to me] all the things that happened to my parents, or your grandparents, or your great-grandparents are all in you, because you wouldn’t be here had in not been for those things that they did. So all it really takes is for you to understand those things, for you to know what those things were, for you to remember those things and then you’ll become a part of it forever. So it doesn’t go away it still stays, and new things are going to happen, new things are always happening. New things are always come our way. New things don’t make us new. We’re always going to be the same people, we’re always going to be the same kinds of people. And she said I Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 17 expect that things will always be that way. So the things that happened the things that are going to happen they are all part of you and a part of all of us now. This is our responsibility to live that way. And that didn’t bother me, but I thought about for many years because I really didn’t truly understand what she was talking about. It sounded like so many things, but in fact all she was saying was that the most important thing is not how things were, the most important things is about not about how things are now, the important things who you are and what you are because that will outlast everything else and you have to be somebody, you have to be something otherwise you are nothing. And so being what you are now and the only thing that I could think about what she was talking about is being Cherokee, being a part of that world, having come from that world, the important part of it was to always be that way and not lose your way, because that’s all we have, everything else fleeting, everything else changes. TC: That makes sense. I think it’s always, being Cherokee and growing up with the culture it’s always helped me know who I am. And I know that’s the first thing I would think of if somebody said, who are you I would always think I’m Tonya and I’m Cherokee, I’m from Cherokee and that’s the first thing that I would always say. And it helps me and not realizing it, it helps me live my life and decide what’s right from wrong, the things that I have to do, that’s always I guess what I base all those things around. TB: It keeps you connected. TC: I know I’ve talked to you about this before, but I’ve done a lot of things outside of the Cherokee community here and it’s always been important to me and my mother always told me that I have to represent Cherokee in a good way, in a positive way because when I do leave, unlike so many other people, I’m not just representing me, I’m not just representing myself or even my family, I’m representing thousands of people because when a person meets me and knows where I’m from and that I’m Cherokee they automatically think all of us are like that. And if they have a good impression of me then they’ll have a good impression of Cherokees. If they have a negative impression then somehow it makes them have a negative impression of Cherokee as a whole. TB: So do you think that, do you think that we can agree on something that in the end it’s all about being [inaudible] whatever that is, in other words whatever it is that you know how to do in your lifetime, like for example in knowing how to be a doctor, or knowing how to be a lawyer, of knowing how to be anything, an engineer, is knowing how to do something it’s a skill, it’s a great knowledge, it’s a great thing, but beyond is the most intrinsic thing, it’s not just in knowing how to do stuff, it’s actually the being something so that as long as you are Tonya Carroll, Cherokee, from Cherokee, the next thing could very well be I’m also a doctor, I’m also a lawyer because being that is the first thing and everything else is just stuff you know and stuff you’re good at and things you can do. Kind of like being a good basket maker, being a good farmer, being a good mother, being a good father, all of these things are all really just a part of being Cherokee, even being a doctor, even being a lawyer could be being Cherokee, as long as that’s what you are first, as long as that’s where you come from, as long s that’s who you are. I think that’s what I would pass down to anyone, is that you can do, you can learn how to do many things, you Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 18 can become a craftsman in all of those things, but if you loose that intrinsic connection of being Cherokee than that’s all you are then, you’re just a lawyer, or you’re just a doctor, you’re Tonya Carroll doctor, Tonya Carroll lawyer, but you’re no longer Cherokee anymore, that’s just another part of the thing that you are, it’s like holding a card, you can pull that out, but it really doesn’t mean anything. And life is changing [inaudible] and I think that’s what my grandmother was saying and I think that’s what I would want to pass down the same thing is that [inaudible] And I think a long time ago when you were in about the 4th 5th grade, I think we might have taught you in class that you can be anything you want to be, but you can never give up who you are. I think that probably that’s the important thing, always remember you being, being something is the most important thing. I think that’s what you’re talking about. Is that down deep there’s always going to be that. You didn’t have to prove to anybody, you don’t have to pretend anything, because it’s all inside of you, it’s who you are, and then you go about the business of achieving, doing all the other stuff and learning things and being involved in the world, but with great confidence because you know who you are down deep, you know that’s what you are, that’s where you come from and that’s being Cherokee, that’s the thing that’s not written on the cards, and it’s not on those enrollment cards. TC: You hear about people and see it in movies and read it in books, and know people that their whole life they struggle trying to find who they are. And I’ve always thought I don’t have that problem, I know who I am, I’ve always known who I am and that’s the main thing in being Cherokee that’s who I am. And I don’t know if you remember when we had that Cherokee language class and we had the big conversation about if you if both your parents were Cherokee but you grew up in Choctaw and learned all their culture and their ways, were you Choctaw or were you Cherokee, and we had a man in there that I went round and round with him and finally I said why do you care what I think what you are, what matters is what you know yourself as, who you know you are, it doesn’t matter what I say, or what Mr. Belt says, if you say you’re something and you believe it than you are that. And you don’t have a card or some certificate saying, it's just how you live your life and hopefully you know that’s what I did when I like to… I don’t know. I’d like to think that’s how I live my life. DB: Just one quick question Tonya, do you see many young people that feel like you do now in the tribe or are they becoming more and more? TC: There are, I found a lot especially now with my job at Qualla Arts and Crafts I’ve gone to several meetings, and I’ve gotten to meet a lot of people around my age, some are even a little bit older that have that interest in the culture and that appreciation for keeping it alive and keeping it going. And especially with our new immersion school there’s a lot of people and people my age that have kids that put them in that school, they want that for their children. So it is growing and more people are being are being vocal about it and it’s really great the things the we’re doing in our community now. DB: Now I’ve got to ask you the question that you ask every craftsman in here, what do you feel about the future about the culture and the language? Tom Belt Transcript June 2010, Mountain Heritage Center 19 TC: I feel really good about it. I think we’re taking all the right steps and moving in the right direction to… one thing that always bothered me was people accepted me into it, and people feeling comfortable with teaching me and telling me and that’s really not an issue anymore. I think more people are coming out and doing their part to pass it on because they’re realizing that it’s not up to the young people to learn, they got to meet them half way and be willing to teach them. DB: Anything else? TB: [inaudible] uncomfortable TC: I want to say one thing. It’s really hard to learn Cherokee as a second language and it’s frustrating and you struggle, but having people there that want to teach you and are willing to spend their time, like Mr. Belt and Sally Smoker and Nonni Taylor and all these people that really put forth the effort to help just really inspires the second language learners. It makes them want to learn. It’s hard. END OF TONYA CARROLL AND TOM BELT INTERVIEW

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

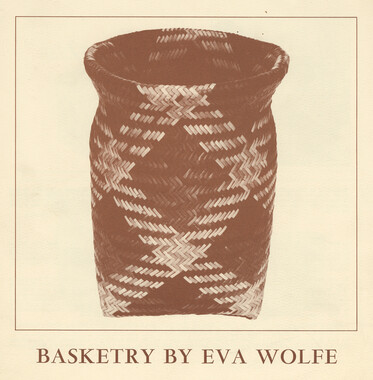

With Cherokee as his first language, Tom Belt’s life work consists of spreading the gift of the Cherokee language. In this video interview, Belt gives background into the development of the Cherokee syllabary created by Sequoyah. The transcript provided is an unedited version of the video.

-