Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

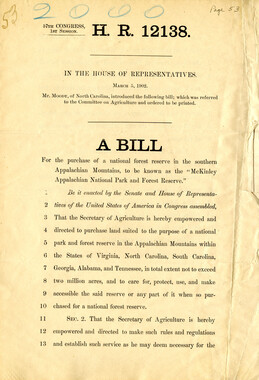

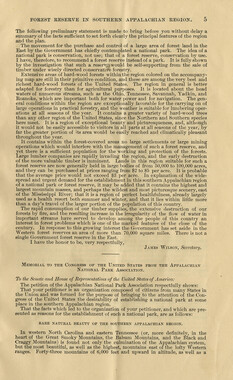

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

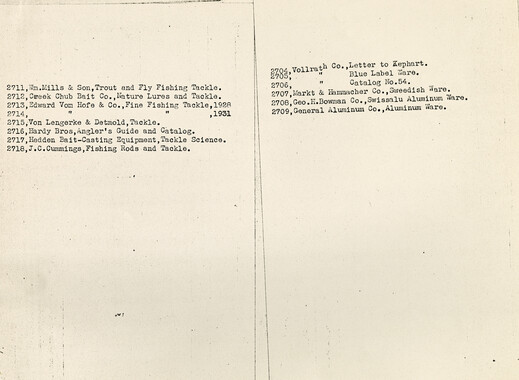

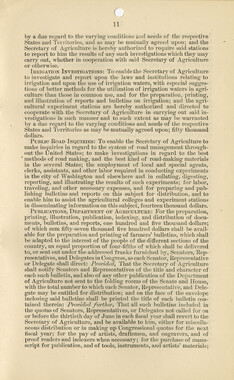

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (19)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

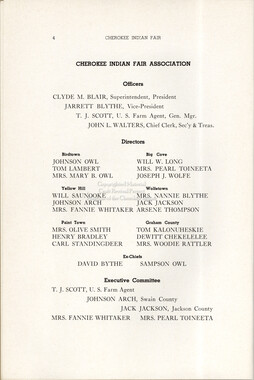

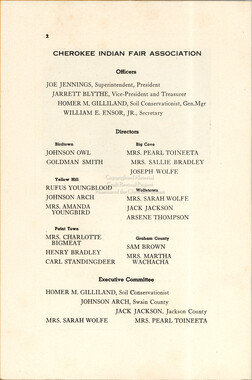

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (1)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (65)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (12)

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association (0)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (0)

- Berry, Walter (0)

- Brasstown Carvers (0)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (0)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (0)

- Champion Fibre Company (0)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Crowe, Amanda (0)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (0)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (0)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (0)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (0)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (0)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (0)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (0)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (0)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (0)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (0)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (0)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (0)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (0)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (0)

- North Carolina Park Commission (0)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (0)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (0)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (0)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (0)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (0)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (0)

- Stearns, I. K. (0)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (0)

- USFS (0)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (0)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (0)

- Western Carolina College (0)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (0)

- Western Carolina University (0)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (0)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (0)

- Williams, Isadora (0)

- 1800s (2)

- 1890s (6)

- 1900s (7)

- 1910s (1)

- 1920s (3)

- 1930s (13)

- 1940s (37)

- 1950s (12)

- 1960s (7)

- 1970s (38)

- 1980s (11)

- 1990s (2)

- 2000s (3)

- 2010s (38)

- 1600s (0)

- 1700s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1860s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 2020s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (256)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (2)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (1)

- Qualla Boundary (285)

- Asheville (N.C.) (0)

- Avery County (N.C.) (0)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (0)

- Clay County (N.C.) (0)

- Graham County (N.C.) (0)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (0)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (0)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Macon County (N.C.) (0)

- Madison County (N.C.) (0)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (0)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (0)

- Polk County (N.C.) (0)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (0)

- Swain County (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (0)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (0)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (3)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (3)

- Interviews (12)

- Newsletters (1)

- Photographs (208)

- Poetry (2)

- Publications (documents) (46)

- Sound Recordings (22)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (12)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Manuscripts (documents) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Personal Narratives (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Transcripts (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

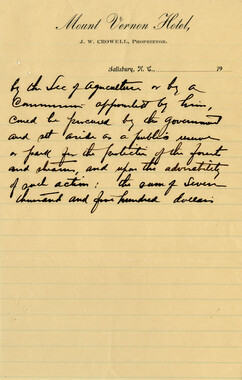

- Horace Kephart Collection (1)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (0)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- Artisans (125)

- Cherokee art (18)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (27)

- Cherokee women (140)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (1)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (1)

- Storytelling (5)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (1)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (14)

- African Americans (0)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Education (0)

- Floods (0)

- Folk music (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Hunting (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- Mines and mineral resources (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- School integration -- Southern States (0)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- Slavery (0)

- Sports (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- World War, 1939-1945 (0)

Sylvester Crowe: Cherokee Bow Maker

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

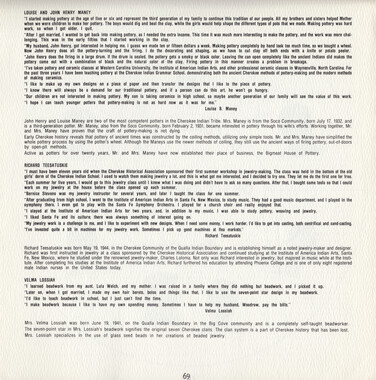

Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 1 START OF TAPE ONE SYLVESTER CROWE INTERVIEW Tonya Carroll: Today is Monday March 1st, 2010 I’m here with Mr. Sylvester Crowe and we are going to talk about some Cherokee traditions. Can you tell me a little about when you were born and where you are from and just growing up in general? Sylvester Crowe: Yes, I was born at the head of [Big Witch] it was at that time it was a real remote area. We didn’t have much a lot of contact with the outside world. We basically was one family that lived in that area. We had no churches up there at that time. But even though we had no churches we still believed, our parents believed somewhat in the sort of Christian traditions. We would they’d all work hard all week and then on the weekends we’d get to have time off. On Sunday we’d get to go fishing if we got our work up. If we didn’t we stayed home, but we didn’t have to work. But before WII in the late 30’s the… they would get together all the older people and they would have different games they would play. For a long time they all played marbles. And they at that time we got glass marbles. So mostly we used glass marbles, some of them still use clay, but we didn’t have a lot of clay in that area so we didn’t use… have a lot of clay to make marbles. But then, later on we got to about the same time they was getting to make… shoot bow and arrow. They they were just, I’d like to talk about how the bow and arrow was made, and I’d like to tell you a little something about the yellow locust. It was a very hard wood, and it’s very strong. They… we used yellow locust to make wedges, when they cut trees they could use them, we didn’t have metal wedges so we’d use the yellow locust. We also made the darts for blow guns out of yellow locust, the shaft of it. And of course used for bow and arrows, we used yellow locust for stakes to go in the ground to put our fence posts, as fence posts. If you wanted a real quick hot fire you could use yellow locust and burn it, it would make, back then they said “burn a biscuit.” So yellow locust was a very important wood to us. And to that I’d like to move on from the yellow locust to the use of the bow with it. To my understanding at this period of time there was no bows made out of anything but yellow locust. They would find the yellow locust. It had a very poor root system so they fell. So finding yellow locust wasn’t very hard because there was a lot of it in that area. The… they could choose a locust that they needed by just looking at the locust whether it would make a good bow. They had a very good eye for it. They would take the locust, and take it home and by that time we was introduced to metal tools. So they used a lot of metal tools to make the bows. Had their [draw] knives, of course we had an ax and saw. We had some metal wedges. If we didn’t we could use these wedges made out of locust. Cause you’d get softer wood for a maul and it wouldn’t tear up your locust wedge so fast. So later they would start on weekends, I don’t know whether it was Saturday or Sunday and they would shoot bow and arrow, they did it for recreation and just target practice. It was time of relief from the working all week hard. That was a relief out for them. They could practice some of the traditional bow and arrow shooting, just a working with the bow and arrow, making them, making the arrows. They made the arrows out of hickory, they’d split hickory, make the shafts out of it and sometimes they would also use Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 2 sourwood sprouts of course the sourwood sprout they couldn’t sharpen the ends of them so they would use yellow locust. To the best of my memory they’d use the yellow locust and put a point on the shaft of the sourwood. And they put the feathers on by that time, they was putting three feathers instead of two feathers. We didn’t have no mountain cane or river cane in that area so that just wasn’t an option for us to make the shaft for the arrows out of. TC: Okay. Can you tell me a little bit about how you learned to make the bows and arrows, who taught you? SC: Yes, I watched my father or my daddy how he made them. Of course I think a lot of your crafts runs… your parents do it, you do it. I think you inherit the gift of making crafts from your parents. At one time it was necessary to be a craftsman. Whether it was to make a sled or a to pull behind the horse, or to make [pv] handles or ax handles, or anything that you needed you needed to be a craftsman at that time whether it was to make the shingles for your house, for a roof, whatever the necessary things that you needed people was a natural craftsman to make all that stuff. So I think we’ve inherited a lot of our ability to do crafts this day and time. We have explored other type, making other types of things except what was necessarily needed. They could hew logs for a house and it looked like it had been cut and milled. They were just handed down from necessary needs to perform different duties around the home. TC: Can you tell me a little bit about your parent’s and their names and where they were from? SC: Could you repeat that? TC: Could you tell me about your parents their names and where they were from and their parents. SC: My mother came out of the Wilnoty family, she was a Wilnoty. To my understanding, the Wilnoty’s came from down around Murphy, Tennessee, just before the removal or during the removal they settled in on a place called [Rock’s] Creek now. Brought his whole family with him and from… had homesteaded then. And from there, from that point on down to now the still Wilnoty family still exists. It wasn’t pronounced Wilnoty at the time, it was I can’t pronounce the Wilnoty name, but anyway, it was an Indian name at the time. But he brought his whole family. He was like 100 years old when they moved in up there and his wife was around 90. So they made that trip from down there to [Rocks] Creek sometimes before or during the removal. They didn’t want to go west. My daddy’s people was Crowe’s. As far as I can trace him back they was came out of Nick Bottoms down Birdtown. They was actually Nick’s to begin with. Second generation I could find changed to Crowe and by that time he moved to Wolftown. So from the removal from Birdtown to Wolftown one of them became a council member. Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 3 Was name… And then another, later on one of the uncles became chief. The Crowe’s have been in existence in that area since 1700’s. TC: To your knowledge did any other Cherokee communities participate in the bow and arrow target shooting? SC: Not in our area. It was mostly just a community gathering. But I do know that a section of Big Cove at one time they also practiced bow and arrow. They even shot for competition up in that area at one time. Around the area that is known now as [m…] fields and then on up in the Big Cove area. They shot. Different communities practiced different traditions. Big Cove really held on to a lot of the traditional dances. More so then… At one time Paint Town had some traditional dances. I know Wolftown held onto Indian Ball, Cherokee Stickball. Up where we lived I don’t know if it was as much traditional or just something to do on the weekends where everybody, the older people meeting like I say, at one time they’d play marbles and another time they’d be shooting bow and arrow. Everybody had chop block so they’d get around chop blocks at night and [build up gnat smoke] and sit around and talk into the late night [about] bow and arrows. Then when they’d start home they’d have a little, they had a bottle and they had kerosene in it with a rag stuffed down tin it and they lit that rag and that was their light that they used for a light to go home with. Or to get out because at that time there were still a lot of rattle snakes around in that area and you didn’t want to get out at night without some kind of light because the possibility you’d step on a rattle snake was pretty good. TC: While you were growing up you said in the 1930’s? SC: I was born in the middle 30’s. TC: At that time I now that they were having the Cherokee fair. Can you tell me a little bit about that? SC: Yeah, the… at one time, we’ll go back a little further than the fair, at one time they would let all the children out of school, like boarding school at a certain time in the fall of the year and they’d go and help get the crops up. The crops are very important to survival during the winter. Later on they when the fair got to growing big and developed to pretty good size enterprise they let their children out during the whole week of the fair. So at that time you could only go to the fair one day a week, but you’d come down early and you’d stay all day and your parents would bring you a basket with food in it. Maybe if you get lucky you’d have fried chicken or a sandwich of some kind. And you’d stay at the fair all day. Dinnertime we’d meet either down at the stands or go up to around the back side there was a little branch up there, we’d go up along side that branch and eat our dinner or eat or there was a little ridge up there and had apple trees up there and we’d go up there sometimes. Or just at the head of the stands where people sit and watch… just up there and sit down and eat. But it was a very unique experience I guess you’d say to go to the fair. We didn’t know what cotton candy was or we never got popcorn or hamburgers or whatever you could see down there. Ice cream, that was one day event of the year. They’d give us a dollar most of the time, if we could get a dollar and it would last you the Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 4 whole day. You’d start figuring out by dinner time how you were going to save your dollar, what was rest of your dollar the rest of the day. But the festival was… at that time too everybody, the communities participated very well in the community tables. Everybody brought a little something down to exhibit in the fair. My mother greatest thing was she always put honey in the jar, or can that was one of the things she always bought. Another thing she carved and she always put her… she carved a set of pigs, a mom and papa pig and the babies. And she always put them on exhibit. And that way we got a free pass to get in. TC: So while the kids were going out and trying to spend their dollar, what would the parents do? SC: Well sometimes you’d get away from your parents, if you were a little older you’d get away from your parents and you could run around the festival by yourself, but you always remembered you only had a dollar and that had to last you all day. TC: What kind of activities other than the different types of foods would they have at the fair. SC: They had a very big carnival. It covered this whole [bottom] at the time. They had a bunch of side shows, of course children couldn’t go to them. But they had rides for the adults and for the children. And at that time the people lined up to get on the Ferris wheel was adults it wasn’t children. The children had their children rides, but the adults also joined in on the rides. So if you wanted to get in line you had to get in with the adults because there was more [laugh] adults in line than children. TC: Did they have like stickball and dances at the fair? SC: Yeah, they had… at that time the communities played each other in stickball. Down at Big Cove, Wolftown, Paint Town, Birdtown. I guess that was all the communities. But they, two would play early in the week and they would keep on and then the two that ended up at the end of the week would play each other for the championship. And like I say Wolftown had more of a traditional Indian ball or stickball and they… I can’t never remember at the time that they got beat, but they… that was our big… of course they had some awful tough battle out there from time to time. Yeah, there was Cherokee stickball and then they had their traditional Cherokee dances and some… they had I can’t remember much other than the stickball and Cherokee dancing they had out there that they had on the stage. TC: Did you play stickball? SC: Yes, when I was small, was small, I played at Soco. The schools played each other too. We had three day schools and one boarding school and we played each other. TC: So which school did you go to? Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 5 SC: I went to Soco. Soco Day school after… it went to the 6th grade, after 6th grade I went to Cherokee school. That time it was a boarding school, plus a day school. What I mean by day school, you went during the day and went home at night. The boarding school they stayed there at the boarding school. During the whole year. We had other students from other tribes come in and join in the boarding school because they didn’t have a school system on their own reservation so they came here. TC: Did they teach any Cherokee traditions or crafts in the school? SC: Sadly they didn’t. It was mostly your ABC’s at the time or reading writing and arithmetic. Basically all they taught. TC: You said that your mom she was a carver? SC: Yeah. TC: Who did she learn from? SC: She was a great craftsman, but I don’t know that she ever did any before she started helping raise a family. A lot of crafts were done out of necessary. We’re able to take them and sell them, get a couple of dollars, but she basically learnt from my daddy. Or she took it up [inaudible]. My daddy carved to start with like he made the bows and anything he wanted to make with hands. So she picked it up from him and became a great craftsman. TC: So what Cherokee crafts do you make? SC: Well at one time even when I was, before I was probably 5th or 6th grade we used to make different things, carvings. We used to take laurel and we could bore a hole through the… and make a tie, a bolo tie for like boy scouts used with an Indian face on it. Then we would I tried to carve some pigs, but I carved a horse from time to time, or a dog, but then after I got into school Amanda Crowe started a wood carving class about the time of the entering of the boarding school and the closing of the Dairy Barn. So that was a great time for me to change from working at the Dairy Barn and out in the fields to going to wood carving class. So I got a lot of influence from my mother plus a whole lot of influence from Amanda Crowe. I do big work and I also did little hand crafts whatever I felt like doing. TC: Are you related to Amanda Crowe? SC: Way off I guess. Not anything close. TC: Whenever you would do some wood carving can you tell me the process that you’d use, would you go in the woods and get your wood? Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 6 SC: Well a lot of time we did. But some of our big sculpting work we did at Amanda’s was able to buy some of the wood. But there was still a lot of wild cherry on the ground and sometimes we could go get some of that by sawing it and bringing a block out. Taking it and carving it. And sometimes somebody would bring a big log in and sell it to the school and you could get some of that. When we’d made a piece and sold it then we could get give the money back for the wood that was used. TC: Did you have a pattern that you used? SC: No, we just and a lot of the small stuff we used a pattern, but our sculpturing we just took a piece of wood and looked at it and seen what we wanted to make out of it. But like I say Amanda was a good leader and she would help us to show us what a piece of wood could develop or you could make out of the wood. TC: Back then, was it pretty common for women to be carvers? SC: Not as much as it is, well no, it wasn’t very common. Most of the women did basketry and woodwork, I mean beading and stuff of that nature. It wasn’t as much common for a woman to do carvings. Since you’ve mentioned it I don’t remember. Right off hand there probably was, but I don’t remember a lot, besides Amanda and my mother, women that really did great work or did a lot of it. TC: When Amanda started teaching those classes were girls allowed to be in the classes? SC: Yeah, oh yeah, some girls came, but I don’t remember any of them that ever… in my time, there may have been after I got out of school, there may have been some of them that came on and did some good work. But I’m sure they was capable of doing it, whether they was interested in it or not I don’t know. TC: Okay, did they have any other classes, did they have basket classes that girls could take or? SC: Yeah, they had weaving and basketry and I think they may had some pottery too, I’m not for sure. TC: Over the years what all different types of woods have you used and what did you use them for to make your carvings? SC: Our basic wood was wild cherry, [that’s what most people around here use] or either black walnut. Later years we started using [inaudible] buckeye. In the earlier days the buckeye was used mostly for masks, the people that made masks I never made mask so I didn’t have much use for it. I didn’t use buckeye very much in carvings. But through the years the wild cherry got scarce and other type of wood they start reverting to, using buckeye and [bass wood or lynn] and then buckeye or white walnut to carve. Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 7 TC: Say you were going to make something that you commonly made, how long would it take you the whole process from going and getting the wood and letting it dry out? SC: Right now about all I make just earrings, I make stickball earrings. My total time that I put in, I can’t do it all at one time, I’ve got to go in 3 or 4 hours to make earrings that I sell a set for 15 dollars, I may have 5 hours invested in those earrings. But like time I may put 15, 20 minutes for one thing 30 minutes for another, 1 hour for another. The drying time, letting it… it takes a long time. You can’t never get… if you went on hourly wages, you couldn’t set it for what your hourly wages. Even the bigger carvings, by the time you go to the woods and either go buy it or go gather your material to use, letting it dry. It takes a lot of time especially in your basketry, probably take more time for that then it does getting wood to carve with. TC: I’ve heard people talk about when they go and get their wood that they have to leave it sitting to let it age. SC: Yeah. TC: Can you explain that to me why they have to do that? SC: Yeah, the wood needs to be totally dry before you start. If you don’t you run into the problem of it cracking or busting, or splitting. So if you let it dry most of the time the ends are still cracked, you can to cut them off and go ahead and get your. And that way when it dries you can put sealer on it, get it made you put sealer on it and it helps prevents it from cracking later on. Yeah, the... in order to keep it from busting or splitting you’ve got to have it cured. TC: So say I went and I decided I wanted to make something and I cut down the tree. How long would I have to wait before I could start my carving? SC: Gosh you’d have to let it sit, really if you cut a tree down you’d let it sit for a year at least before it seasoned out. So try to find wood that has already been seasoned or either in anticipation of doing some carvings you gather your wood in advanced you have it stored and then you go back and choose whatever you’re going to make out of what you’re going to make. But it would take at least a year for it to cure out good. The harder your wood, the longer it takes to cure. Buckeye or [paloni] it don’t take as long to cure out as say walnut or wild cherry. The softer wood the less time you’d have invested in it curing out. TC: Do you know why that is? SC: The grain is not as tight, so your moisture and your sap and the breakdown in your wood in the curing can escape a lot faster than the harder wood. TC: Okay. Why did you become interested in learning how to carve? Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 8 SC: Well my mother did it and I was fascinated in what she made and I tried to make something. And then by the time I got in high school I started working with Amanda. I could make my own money for spending money out of it. And once in awhile I would sell a big piece and get more money than just spending money so I could put a little money in the bank, in savings. So by the time I got out of high school I could have enough money to buy me a car or whatever I needed. So it was a [venture] I guess to create a way of living or a better way of living. TC: Okay. Did you ask your mother to teach you or did you just kind of watch her. SC: I just watched her and she would encourage me and show me where I was doing wrong, going wrong. It wasn't… back in them days if you needed help everybody would flee to you and help you. [Everyone] you didn’t’ have to ask. They seen your need anything whether it was your garden needed hoeing or your crops need hoeing, or you needed a cup of flour or something. If they seen you needed help. So in that type of environment when you would start to do something, if you wasn’t doing it right or you didn’t understand, you didn’t have to ask for help to your parents or your uncles or aunts or grandpa. They’d automatically fly in and help you and encourage you. It stemmed back from that was the way of life to survive for a lot of the Cherokee people in the earlier days. It was a common bond to help each other to survive, I think it came from that. TC: What kind of knives were popular to use for carving? SC: We had we could get a hold of pocket knives or the big chisels, the bigger work, we didn’t have much of that until we got out of… got into school. But at home Dad made a lot of his knives out of he’d get an old file and he could make something to work with. Either we’d get a pocket knife from time to time from someone. And at that time all the pocket knife was had good metal so you could carve with them. TC: So about how long would you say that you’ve been making wood carvings? SC: About all of my life. Some type or another. I never was great carver, just did it for a pastime I guess. [In the last years]. There’s a lot better carvers than I am on the reservation, I’m on the bottom of the totem pole to that round. [laugh] TC: Have you taught anybody to carve? SC: I’ve tried to help my boys and both of them can carve. Yeah, I’ve tried to help them all I could. TC: How have you noticed wood carving change from when you were growing up to the way it is now? SC: From when? Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 9 TC: From when you were growing up? SC: It’s become more commercialized. People seem some of the people seem just depending on the carving for a way of life. For I guess [how you’d say it]. Back then you carved in your spare time in order to, I guess it was a way of life then, but it was to add to what you could dig out in the mountainside or cutting logs or whatever. You couldn't make a living off of just carving. You had to raise a big crop, you had to [do a lot of canning work], did a lot of logging, cut [inaudible], tan bark, [inaudible] wood, and the carving at that time were just to add to and fill in the gaps if you couldn’t get… it was the combined effort of all the resources around you to make a living for you and your children. So carving was at that time was a… I guess you’d say a way of subsidizing the other stuff that you worked with to supply necessary needs for the children and the family. TC: So when you were growing up and selling crafts just to supplement the family income who would buy them from you? SC: Momma could bring carvings to… some of the craft shops downtown, there is one in particular, Miss Wilson they had a shop down and a lot of people sold to her. There was other craft shops that bought from. Later on in the 50’s I guess it was, early 50’s they started selling the local people had the information [hut] down here and they would people would stop in and they would take people out into… touristers out into the community that did crafts and they would buy from us from time to time. Some of them, I think that was beginning of some of the people started depending more carvings and the sculpture work for sales to make a living on than they did before that period of time started. TC: Can you recognize your own work if you saw it? SC: Yeah. TC: Is there a certain aspect of it that makes you know that it is yours or can you explain that? SC: No, not really, not a… I guess you’ve just see in your own mind what you’re… you’ve got the picture in your mind what you make and you take a picture to mentally. And once you see it again, it’s just like looking at a photograph of [yourself]. TC: Can you tell me you know the first time you finished your first carving on your own how that made you feel? SC: Yeah the first time…it probably wasn’t my first carving, but I had carved a horse. And Mom, I showed my mother and she was very proud of it, she said that I need a little extra money, can I take it and sell it. And that was one of the greatest moments or achievements of my sculpturing or carving. She looked at a piece of work, but she was a Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 10 perfectionist, and looked at a piece of my work and ask if she could sell it with hers it was one of the greatest moments of my sculpting life. TC: Can you explain the importance of keeping woodcarving going for the Cherokee people? SC: I think that with all the… due to the commercial carvings that we do now, the way that we do it is a more of a commercial type of way of life. I think it still relates back to days that people did it for ceremonies. They would in earlier days they would make masks for dances or I think we should look back as those relate it back to those days when people did it for a way of life. Different than the way of life is now. But in the general sense it is the same way. They did all the masks and carvings for the ceremonies and the dances it was… it was a way of keeping everybody together in one common goal and today we do it for to keep supply necessary need for our families. TC: Since you know how to do Cherokee woodcarving do you feel obligated to pass it on? SC: Well as I said awhile ago I’m not one of the best. And I think they have better teachers that can encourage it and I think it should be encouraged. But we have much better teachers than I am. So yes I think it should be handed down and taught, if nothing else as a tradition. [inaudible] some of the traditional parts of our life. The more things that we can keep together and is focused on, the more our Cherokee people can stay together. I think not only wood carving but language and a lot of the other traditions. We need better knowledge of looking at our past so we can improve our future. TC: Can you speak the language? SC: No, very little. [Don’t even know] goodbye, I can’t say good bye. [laugh] TC: Did your parents speak the language? SC: My father would understand it, but he wouldn’t speak it. He understands it pretty much but he didn’t speak it. my mother didn’t understand it or speak it. My grandpa and my grandmother on my daddy’s side spoke it and understood it. My grandfather on my mother’s side spoke it, but my grandmother on my mother’s side, [inaudible] she didn’t understand it. TC: Was there a reason that they didn’t pass the language down? SC: At one time, back during the boarding school days, era, they prohibited the children to speak the Cherokee language. Those that spoke Cherokee in school had a very rough time due to that. I think a lot of them didn’t teach their children because they didn’t want the same hardships put on their children. Some of the people that wanted to hold onto the language, even though the hardships they thought they might endure through the years, they felt it was worth it to go ahead and teach their children the language. Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 11 TC: Besides carving and making the stickball earrings, do you make any other crafts? SC: No not really, I make a bow from time to time, if I have a few hours, just to pass time, if I see a piece of wood or I get wanting to make one, I’ll try it. TC: So carving that is something that you enjoy doing? SC: Yeah, I enjoy carving if I do it as a pastime, I can’t sit down and just carve stuff to sell. I’ve got to be and want to do it, I’ve got to see something that I want to build or make or carve. And really interested in doing it then I can do it. As far as just settin’ down and [doing it a lot] I don’t do that TC: You talked a little bit at the beginning about how people would get together and play marbles. Can you talk about that a little more, like how they set the game up or? SC: They had place out in the yard there where they would… at this particular home and it was flat you know we was in a mountain area so it was hard to find flat. And they had it cleaned real well, no grass, just some dirt. They played what is known now as [rolly hole] and they’d dig, let’s see 1, 2, 3, 4, about 5 holes and they’d have to shoot marbles in the hole and if you missed somebody went in they could shoot your marble and knock it off. They had different games like that that they play, they had one that they’d called drop box, they’d drill holes in a box and you’d have to drop your marble into that box. If you missed they got your marbles, if it went in the box you got two marbles. So there was different games that they played. Some of them they’d… what they called [lay out] you’d put your marble out in front of you maybe 4 or 5 foot and they’d tried to take a marble and hit it. If they hit your marble they got your marble, if they missed or you picked up and shoot at their marble. Try to hit theirs. So that was another game that they played. They had several games, what they call bulls eye, they played that one and then they had they’d draw a big circle everybody would put a marble in there and you’d shoot from the outer side of it and try to knock the marble out. When you shot and knocked a marble out you’d get the marble. And if you stayed inside the ring you’d shoot again. Several games like that they played TC: The parents were the ones that would play the marbles? SC: Yeah, mostly older people. TC: So what would the kids do? SC: They’d be watching. Find other activities to get into. But that, when I was just a child it was mostly adults that played the games. Children didn’t participate with them. TC: Do you remember if they would bet on it or gamble on how the game would end up? Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 12 SC: No, I never did. And I don’t remember them doing it it was more for fun at that time. There was not much gambling done as far as the… on the game itself. TC: Well I think that’s all I have. Do you have something else that you want to talk about? David Brewin: I have a question I’d like, you were talking about those bow and arrow competitions SC: Yes. DB: And were their prizes for the winner? SC: No there wasn’t no prizes, whoever did the best they would they’d make their own darts and whoever got nowadays I guess you call it a bulls eye and whoever could get more arrows in it to the center. It was more just competition in itself, no betting and no prizes involved. DB: So how would you set up something you said the different townships would sometimes get together and have a competition how would you set that up? SC: It was just automatically every weekend, if it was pretty weather like I say they’d work all week and I don’t know if it was Saturday afternoons or Sundays, we didn’t go to church then, there wasn't a church in our area. It could have been Saturday afternoon or Sunday evenings they’d meet and they just, every weekend thing during pretty weather they’d do it. TC: Like was there a certain person’s house that everybody would go to? SC: Yeah, they, sometimes they’d be at our house, sometimes my grandpas and then another home on down the road. The other home down the road mostly they would play marbles, but they also shoot bow and arrow down there. TC: Do you remember if they had like a competition at the fair? SC: They had bow and arrow competition but none of them ever participated in it, it was mostly just for… their own little own community to associate with each other. TC: Have you noticed a change in how the communities associate with each other? SC: Yeah, I have a big change. At that time everybody knew each other and was willing to help each other and nowadays, today, it’s a faster way of life with cars and the trucks, and going here and there we don’t have much contact with our neighbors. Not unless we contact them out away from home somewhere, at a ball games, community club or work or something of that nature. And in the earlier days the people depended on each other. So there was one reason for more contact with each other is neighbors. They would about Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 13 every community had a work crew or they’d go to people’s houses if you got sick or you was getting behind on something they’d send out messengers and they’d all come around your house. And they’d cut your wood, or hoe your corn, potatoes, your garden, whatever you needed to do. As a volunteer and work if it came around. DB: And one other thing I was curious abut was the boarding schools, how many students were in your school that you went to? SC: The boarding school? DB: Yeah. SC: Well it went from 1st grade to the 12th grade, when I was there. My mother and daddy it went from the 1st grade to the 8th grade I think. But there was probably 30 students in each class that would be from boarding school, it was also a day school, so there wasn’t that many I don’t know, there wasn’t a real whole bunch of them, but there was quite a few too. DB: So they’d be bringing in other tribes SC: Yeah, other tribes were the boarders. DB: What other tribes? SC: There’d be some from Mississippi, some from Florida, some from Virginia. TC: Did you play on any of the sport teams they had at school SC: Yeah, I played football and baseball. I played basket ball, but not on the high school team, we’d just get a bunch of boys down there and during recess or whatever. Then we played softball a lot. We played a lot of different sports. TC: Was there a boxing? SC: Not in my time. Before I think there was a man who did have a boxing team and then a little after I got out of school they got a boxing team but it wasn’t related to the school, it was related to the individuals. TC: I think you might have grown up around where my grandpa grew up. His name was Phillip Smith. SC: Yeah TC: Did he grow up there around you? Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 14 SC: He was about a mile and a half, two miles from us and he was one of the neighbors. Since you mentioned him I’ll tell you a story about his dad, Phillip’s daddy. TC: Okay SC: My mother was home when Daddy was off in logging camp or somewheres. She might have just run him off for a week, I don’t know. But anyway he wasn’t there. One of my brothers cut my fingers off. My mom, of course it was getting late and by the time she got the neighbors to come up and watch the children and got me ready to take me to the hospital, didn’t have no vehicles up there to ride so she had to carry me. When she went down by Norris Smith, which is Phillips daddy, went by his house he was going out to the barn to milk the cow. He was hollering after where she was agoing, she told him what happened. At that time people didn’t leave home at night just going somewhere down the road like that, so he just hollered back at the family and told them he was going to help my mother carry me to a hospital so him and her carried me to the hospital and at that time [inaudible] road was about ten miles. So they carried him to the Cherokee hospital. I always remember… I didn’t remember it, but I can remember them telling me about what happened. TC: How long would it take you to walk from your house down into town? SC: [inaudible] road was it’d take probably and hour and a half to two hours according to how hard you wanted to walk or run. When you was a small, young ones we would run all the way down if we was coming out for something. We would stop and walk by the houses, everybody had dogs and you run to the house about time the dog would chase you so we would stop and walk by the houses. Other times we would run. It didn’t take quite as long that way. [inaudible] children that was going out. But we didn’t get to come out very often, maybe once or twice a summer in the beginning. Other times we came out a little [inaudible] or [inaudible] with our parents. DB: One more question. Did you raise any meat type animals like a hog or anything like that when you were coming up? SC: Hogs, chickens, if you was fortunate enough to have a cow. The hogs and the chickens was necessary, that was some of the things you had to have to. The chickens not so much for the eggs, but for the meat. The hog, you had to raise the hog to have meat during the wintertime. Everybody killed a hog. Put it in… cured it outside, no electricity. We’d wait until it got cold and cure a hog and keep it cured outside. With salt and other mixtures they would mixed together. DB: Did you ever smoke it after you salted it? SC: Do what? DB: Did you smoke the meat after you salted it. Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 15 SC: No no we did smoke no meat, there maybe some people that did, but we didn’t. It was just salt cured meat. DB: How about hunting did y’all do any hunting for meat? SC: Yeah, I had an uncle that was a very good hunter, my mother’s brother. And he could kill 1, 2 maybe 3 bears a year. And I remember my mother canning it. She’d divide it out and everybody would have bear meat in cans or jars for the winter. If you could kill a groundhog you’d have a feast then. Groundhog was a very good prize to dig up and catch. We’d particularly go groundhog hunting, go squirrel hinting and you’d take 1 or 2 maybe 5 shells with you hunting. You didn’t waste none, you didn’t shoot one until you got a squirrel in your sites or it was something that you could eat. We’d also kill what we called [bloomers]. They was smaller than a grey squirrel. But if I could kill 2 or 3 of them I could take them home and clean them my mother would make squirrel dumplings with them. It wasn't very big to eat, but they made good dumplings. Yes, hunting was a very important part of our life too. DB: Now, when you all were hunting bear were you using dogs to hunt them? SC: No, I’ll leave that for another time. I’m not especially crazy about hunting with dogs. TC: So did when you guys were hunting what were the women doing? SC: They stayed home. The women always had more work at home than they could ever get done. If it wasn’t taking flour sacks and making clothes or working on quilts for the bed, preparing meals. They prepared three big meals a day. So the women’s work was never done. She had very little time to relax. Most families had big children, big families, and it was basically up to the mothers to raise children inside the house. Darn their socks, make them clothes, make sure they had their washed behind the ears, something [inaudible] eat. Women at that times had more work than you could ever get done. TC: Let’s set up so you can talk about the bows and then I think what time is it? DB: It’s about 20 to 11 I’m going to change tapes. SC: I need to go to the bathroom anyway, and find my coffee what did you do with my coffee? TC: I don’t know I think it’s sitting. END OF TAPE ONE SYLVESTER CROWE INTERVIEW START OF TAPE TWO SYLVESTER CROWE INTEREVIEW Tonya Carroll: Explain what you have over there on the table, and what you brought in. Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 16 Sylvester Crowe: Yeah, I would like first some carvings that my mother did. As a small child coming up she always carved these. She could do other carvings, but everybody that she sold them to wanted her to make these because it’s unique and nobody else carved them. It took a lot of time and effort. You’d go to the woods and get the timber and Dad would have to take a hatchet or ax and trim it down to the width that she wanted it and then she’d take a little coping saw and saw them out. It took a very long time to saw them out and prepare the wood and get it to that shape. Showing small wooden carved pig about 4 inches long. Shiny with great amount of detail. TC: What kind of wood is that one? SC: Now this is cherry, it’s a real light colored cherry, but it is cherry, now here is a darker type of cherry and she also did this. Showing baby pig laying down about 2 inches long. It also is shiny and done in great detail with one back leg sticking out behind it. It’s a little pig went with the mother pig. This is the mother pig, pointing I guess to the first pig shown off camera. She also made the male pig the same size. And they were in a set. She had five of these pointing to the small pig. I don’t have but four of them and they wasn’t made for the same set, right here is one she made and it stands straight. Showing an even smaller pig, maybe 2 inches long. Standing up. It’s made out of curly maple, which was a very hard wood but she found the wood and it’s pretty so she made little pigs out of them. She also made a whole family of pigs out of them. Right here’s a different. Now this is kneeling down like it's a nursing. Showing small pig also about 2 inches long. Pig’s front legs are bent at the knee and his nose is touching the ground. (All baby pigs as seen sitting on the table appear to be at most a quarter of the size of the mom). She made I think it was five pigs per set plus a mom and papa pig. That’s when she would take other carvings she did to sell them they would always was her to bring the pigs. Cause that’s… she was known as the one who did the carvings of the pig. Like I say nobody else there at the tribe would make them. That was some of mother’s work she did. Now I’ve got some bows here that this bow here I was fortunate enough to get a hold of this, this bow. Showing dark colored bow about 2 yards long. (Or as long as the couch that Tonya is sitting on). Has a handle carved out in the middle. Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 17 It was made primarily for a hunting bow. It was never used, but that is what it was made for. It’s made out of yellow locust, I think I spoke a little bit about yellow locust before and the… to my understanding from what I was told, the Cherokees always used yellow locust they never used anything but yellow locust to make their bows out of. This was made some time in the early 30’s. And it’s still, probably still be shootable today if somebody was going to take a chance on shooting it, which I wouldn’t do because of age. David Brewin: What’s the string made out of? SC: This string is made out of sinew. I believe they call it. Close up shot of string. Braided and tied around the end of bow. But back at that time they would use rawhide, if they couldn’t get a hold of a good string they’d use rawhide to braid it. Braid three pieces of rawhide together and then sometime on a heavy bow they would take three pieced already weaved together and weave three more pieces together and made it stronger, make one string. Light colored bow, bent more than the last one, also handle in the middle, not quite as notched out. Same length as the last one. This is one of the bows. Right here is a bow… to my understanding I made this one here lately by using yellow locust. I soaked this in water for some time and then I bent it to the shape I wanted it. I got a metal building I put it in the summer, I put under the metal roof, pretty close and I had it bent in the shape I wanted and let it season out that way, so it’s kept its shape. Ordinarily it would straighten out. And to my understanding the way they explain the bows, this is sort of similar to the way the bows were originally made. Except this groove here would have been straight, they wouldn’t have been cut this groove out. Pointing to about the middle of the bow where it is notched out slightly, but visibly. Now there’s different theories and different stories about that, but to my understanding the way they told me is that’s the way the bows was made. They didn’t have the hand grip like I have today. DB: Why is yellow locust such a good bow wood? SC: The yellow locust is very tight grain. And it was very flexible, you could use it for like I say for wedges, you could use it for darts for your blow guns, your bow and arrow you could use for stakes to put in the ground. You could use it for sled runners, they’d build a sled to pull behind the horses, they’d use it for the runners on that. It’s very hard and it lasted very long. And it very seldom ever if you… certain conditions it never would rot. Right here’s another bow that my daddy made. Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 18 Showing darker colored bow also with a handle notched out in middle. Also about 2 yards long or longer. Later on in the years it was also made sometime in the middle to late 30’s maybe 40’s. He also made this one. He never used it he just made it. But it was designed similar to the hunting bow would be one that they just shot for practice, or just for having a community gathering, just to shoot to have something to do. And if you notice this bow is long, he was tall man, so he made the longer bow in order to fit his arms and his height. He would make the bows primarily to the size of the individual. The taller man would have a longer bow than the shorter man. Showing bow, slightly bent, dark color. Handle is wrapped with something in the center. One side rounded, one side flat. Here’s one of the bows that the actually, it was made in the early 30’s and he targeted practiced with this. It was what it was made for. It was made in a different style, it was round with a flat back. Why he changed styles I don’t know. But he actually made this during the earlier days before the WWII and a little after WWII. They gathered up there to shoot bow and arrow. And this is a bow that the used to shoot in target practice. There was no competition, except among themself, there was no betting, just for a friendly afternoon date to have some games and associate with each other. That was his that he used when he target practiced. Showing bow dark color with two curves on either side of the center of bow. No handle in the center. Right here is a bow that he made for my mother, why he put this… I know why he put this in here, Pointing to the fact that the bow is high in the center and dips down on either side, making a shallow W look. He said that it didn't take as much to pull it back, but you got more velocity out of it than you would if it was just straight. Whether this is true or he actually got more velocity out of it [inaudible] I don’t know. I never tried to shoot it, it hadn’t been shot in years, so I wasn’t… but they are all made out of yellow locust. Yellow locust is a very strong, flexible wood it can be used for a lot of different things. They made the arrows a lot of them made the arrow that they did at that time, they would split hickory and make the shaft out of hickory. Showing arrow, ½ inch thick about 2 or 2 ½ feet long with point appearing to be made by shaving off end, but has sinew wrapped around base of tip. Three (two light and one dark) feathers are attached to the other end. The feathers are cut in half and glued from the hollow shaft of feather onto the shaft of arrow. There is also sinew wrapped at the base and top of feathers. They were very good craftsman they could make a very good arrow. We didn’t have mountain cane or bamboo to use. By that time they started putting 3 feathers on the arrows. Some time they could just sharpen the end of a stick made out of the shaft make Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 19 out of hickory and use it for target practice, if they could get a hold of a metal target point they’d put them on it. But most of the time they couldn’t or didn’t. DB: Did you have a way of hardening that locust tip? SC: Not so much of the hickory, but when they use this one here is made out of the sourwood sprout. They could put a tip on it with the yellow locust and with the yellow locust they could hold it over wood and they’d turn it, I mean over a fire and they’d turn it and it’d turn golden brown. They did that before they mounted it onto the shaft. And this is good for target practice. It was not to use of hunting. And I don’t know of any other community ever used this type of arrow. But that’s what they came up with at that time to use for arrows, because it was plentiful they didn't have no other, like I say, they didn’t have the cane or bamboo to make the arrows out of. DB: Can you tell me a little bit about how you would make an arrow, just go through the process. SC: When you made one out of hickory, you’ve got a fairly young hickory, when you cut it, they could tell before they cut it whether it would split straight or not. They did have that gift of knowing one tree from the other, what was good for what. They would take the split the wood into small, square piece by using a knife or a draw knife they would whittle it down to a small shaft about the size of this here. Pointing to the same arrow described earlier. Then they by that time they had got a hold of glue plus string they could put the arrows on. It wasn’t necessarily sinew or any other kind of material to tie the arrow on. Some of them still made the little glue and some of them was able to get a hold of glue to glue the arrows on, the feathers on. They would use chicken feathers, or bird feathers, or grouse feathers, whatever kind of feathers they could get a hold of they would use for the feathers. DB: Why is one feather dark and the other ones are white? SC: This one, they used the lighter feathers for the 2 feathers that went against the bow to keep the string from hitting the feathers from hitting the string. The dark feather usually put on the outside if they had different colored feathers, so they’d know to put the… I imagine in the earlier days, they had to shoot fast or repeat the shots very fast. The darker feather was to they wouldn’t be putting the arrow in the wrong way, shooting it from the wrong side. TC: What did the feathers help it do? SC: The feathers helped it go straight. If you didn’t have the feathers on it the back end may try to pass up the front end or it would keep a straight profile to the target, intended target that it was to hit. If it went straight it would penetrate better but if it was a coming this way it would not penetrate. So it kept a straight line that the arrow would follow. The size of your feathers depended too on the weight of the shaft. If you had a heavier shaft it Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 20 took bigger feathers, longer feathers, if you've got a light shaft the feathers didn’t need to be near as big. This one here is made out of turkey wings. Showing another arrow, but with turkey wings. Feathers are again split in half with their hollow shaft touching the arrow shaft. There is sinew wrapped around the base and tip of feathers. I was fortunate to get a hold of some turkey wings. I don’t remember them using any turkey wing feathers at home at this time, but in the earlier days I understand they did use turkey feathers. This one don’t have the difference in markings the dark feather on the outside and light feathers on the inside. This is made more for show now than it is for actual use. A lot of people don’t know the difference in why the feathers was different colored. TC: Is that made out of hickory? SC: This one, now I don’t have any made out of hickory because I’m not that good of [sculpturing]. I couldn’t make a shaft like they did then. But this is made out of sourwood. DB: When you all used to have those competitions, would everybody make their own arrows and bows was that a requirement? SC: Yeah, basically so, they made their own bows and most of them made their own arrows. I don’t ever remember seeing any store bought arrows being used at that time. One individual may make more arrows than did somebody else and he would share with other people his arrows. DB: What was the target you all were using? SC: They would take straw or hay or something of that nature and make a target to shoot at and they would use some type of paper with paint and some kind of coloring on the paper for the bulls eye. They didn’t have, you’d either get one or two points for hitting the bulls eye or ten points, it just had the bulls eye on it. Basically see who could put more arrows into the bulls eye. TC: About how far away would you be when you shot it? SC: Anywhere from 30 to 50 yards. TC: Did the men shoot against other men or did they shoot against the women too? Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 21 SC: You know I don’t… the men just shot against each other. There wasn’t that many women that shot. My mother shot some. But more just as… not in competition against the men she just would shoot to be participating I guess. TC: Would you have like a big dinner, or eat at home and then go? SC: I don’t remember the dinners and I don’t remember the… I remember them staying late up at night so they must have had some kind of a meal to eat. I know in a couple of cases my mom bringing a black tea kettle out with coffee and it was sitting in that in the fire keeping warm the men could have coffee to drink while they were sitting talking out there. And then I always used snuff or some kind of chewing tobacco. I don’t remember too many of them smoking cigarettes, but it was mostly use of tobacco, cigarettes, I mean chewing tobacco or snuff. TC: Is there anything else that you want to talk to us about? SC: Not that I know of at this time except I appreciate you coming, enjoyed it. TC: I did too, it was good talking to you, I learned a lot. SC: I hope I haven’t led too many people too far astray. But like I say, every community had different [cultures] that they tried to that they kept up with or they participate in. Whether our community came out of these days or out of culture or pastime, or after a hard week’s work they needed something to do to calm themself down and get ready for next week. But soon after WWII when the cars became more available and jobs become more available than work on the mountainside and the farms things like this got away from us. But I do appreciate being able to see and to be a young ‘un and some of this stuff that was still practiced in our communities. It’s a treasure to hold on to and I wished we all could have gone through something like this. Maybe a little earlier in your lifetime, can tell our children or my grandchildren a little bit something about it. We was fortunate enough to see an airplane cross every once in awhile. We’d all run out of the house and go see if we could see the airplane. That was a great excitement so a modern day thing. Been coming slow till after WWII and then they dumped on us all hard and heavy. We had to change lifestyles in a hurry. Come from every day working from day to day to the hustle and bustle of running and [inaudible] more modern world than it was then. I’m just glad that I was able to see a little bit of it. TC: Well I want to thank you for coming, and thank you for coming today, we called you and gave you short notice, we appreciate you being able to come. I’ll let you fill out your paper, you can read it but it’s just saying that we have permission to use the interview. And what we’re going to do with it is make a movie and play it in here. And when we get it ready it might take us a little while to edit, we’ll give you a copy. And I’ll help you carry these back out. DB: Thank you very much. Sylvester Crowe transcript March 1, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 22 END OF TAPE TWO SYLVESTER CROWE INTERVIEW

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

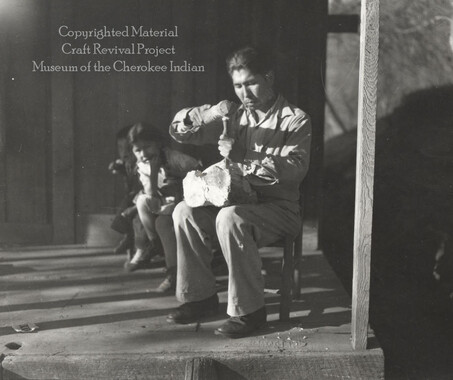

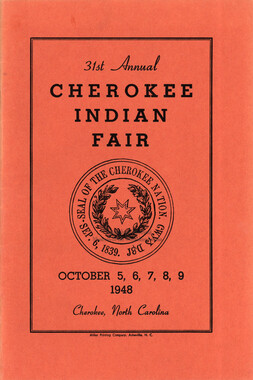

In this video interview, Cherokee carver Sylvester Crowe recalls from his childhood bow and arrow shooting as a social activity for the community, rather than for hunting as it was for his ancestors. He carves his bows and arrows primarily out of yellow locust and adds three feathers on each arrow. The transcript provided is an unedited version of the video.

-