Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

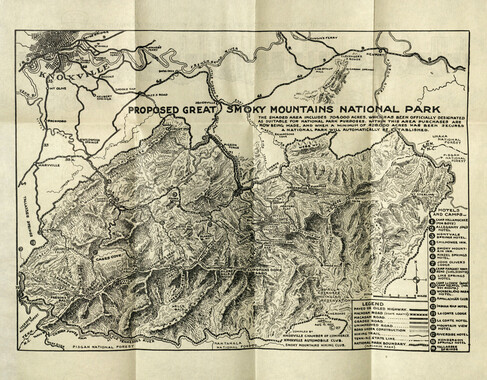

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2683)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (15)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1295)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (1794)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2393)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1886)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (147)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1664)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (233)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (478)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3522)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4692)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (21)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (9)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (211)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (981)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2017)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (247)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

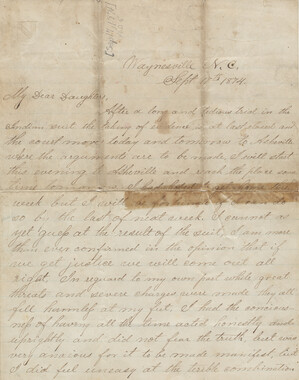

- Waynesville (N.C.) (68)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (184)

- Envelopes (73)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (811)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (619)

- Maps (documents) (159)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (5651)

- Newsletters (1285)

- Newspapers (2)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (12982)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (5)

- Portraits (1654)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (151)

- Publications (documents) (2237)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (1)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (15)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Vitreographs (129)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (198)

- Cataloochee History Project (65)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1314)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1744)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (388)

- Appalachian Trail (32)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (166)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (110)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (1830)

- Dams (94)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (60)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (905)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (154)

- Hunting (38)

- Landscape photography (10)

- Logging (103)

- Maps (84)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (69)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (245)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

Social Development of Cataloochee

-

This 12-page manuscript, titled “The Social Development of Cataloochee” was written by Sam Easterby and George Richardson. The history was collected as part of the Cataloochee History Project that collected photographs, stories, and oral histories about families who lived in the Cataloochee Valley. Today’s Cataloochee Valley is within the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. While, in general, the Great Smoky Mountains region was sparsely populated, the Cataloochee Valley remained an exception. By 1900, the population of Cataloochee had grown to 1,000 residents living in hundreds of log and frame homes.

-

-

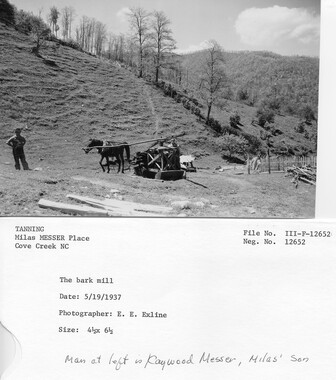

CAT~~fl · . ·, Corl I ''---·~-· ,... _~ .. - -- ~_..:..__.,_,_:, _,......,...Ji...:~- ... .... _c:;.:.,. ' - - - -- ~-- -- ·-·_,;·.,-.. _,,., ____ ,_ .. ~. __ .,. ,.., __ . The Social Development of Cataloochee by Sam Easterby · George Richardson LI BRARY _GREAT SM Of<Y MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK I I This paper will deal with the social development of Cata-loochee from the time of the earliest settlers until the turn of the twentieth century. Special emphasis will be placed upon the opinions held by the people of Cataloochee towards organized religion and education, and whether these opinions were typical to the mountains or not. Why then did people first come into Cataloochee in par-ticular and into the mountains in gener~l? There were a variety of reasons: (1) By the 1830's the Indian tribes of the East had been neutralized to a significant degree. Therefore, many acres of land were now open for white settlement; (2) The land was very cheap, even for that day and time. A good size farm could be purchase~ for less than one hundred dollars; (3) Most of the people that moved into the remote valleys of the mountains were from the lower classes. There was a political conflict between them and the land-holding aristocrats of the Tidewater region, who dominated the political scene; (4) The people in general were running away from "civilization" and all the social institutions that it entails: law and order, courts, education, etc.; and (5) There was really no reason not to move west. The opportunity ; to better one's standard of living was there - jdst waiting for anyone bold enough to sever existing ties with 11 Civilization." Besides the doctrine of Manifest Destiny was beginning to exert l 2 its influence upon the American mind - the lc:ind was open - it was new, it was free and it was "God's 'dill" that it be settled. The first permanent settler that moved into the Cataloochee Valley and began carving out an existence there was probably as fiercely independent as any American who ever lived. This pioneer learned by hard necessity to rely upon himself for his own livelihood. For the most part he was alone - on the fringes of "civilization." The first settler was a many-sided man. He was the maker, the baker and the candlestick manufacturer in his lone community. He planted his corn, cultivated it, harvested it, shucked it, shelled it, and ground it into meal for family use. He bred his cattle, slaughtered as was his need, tanned the hides, and made shoes for himself and his household. He was his own hired man, his merchant, his miller, his shoemaker, his butcher, his tanner, his banker, his teacher, and of times his preacher. He was the provider and protector. He actually was the law - not only in the management of affairs within the home - but also in the relation of the home to the world outside, if there was any. 1 But one day this pioneer touched elbows with a farmer on his right, another on his left, and still another in front and at his back. This was the beginning of the Cataloochee community. By the end of the Civil War the following families had settled in the valley of Cataloochee: the Woodys, Hannahs, Suttons, Caldwells, Messers and the Nolands. It was not long before a certain &mount of inter-depend-ence began to emerge in the people. The first settlers were 3 totally self-reliant because they had no choice. But when people began to move into the valley in greater numbers, inter-dependence ' was the natural result. A good example of this is the skill of the Messer family in handicrafts, i.e., blacksmithing, carpentry, etc. W.G.B. Messer built the beautiful steeple for the Little Cataloochee Baptist Church, and Charles Messer built a four-room addition to the Steve ~oody place. The families of Cataloochee also depended upon each other for trade. Even in the early part of the twentieth century it was still at least a two-day trip to the nearest market town. Thus, the families would barter with each other for the articles that were needed. 2 Social gatherings such as "music making," "quiltin'," "corn-shuckin'," and livestock round-ups served as outlets for the emotions as 'Vlell as serving a practical need, as work and fun were often combined in the same event. The livestock of the farmers in Cataloochee was allowed to roam freely throughout the mountain slopes of the area, feed-ing on wild chestnuts and acorns. Each farmer, of course, had his own particular brand for identification purposes. Before slaughtering, the animal had to be fattened on corn, so a general round-up was necessary. The menfolk would search the mountain sides for livestock, while the children fished for trout in the valley streams. In the evening, while '---.../ eating ample quanti ties of fresh trout, the farmers would ex-change accounts of the livestock they had seen that day. Usually, 4 these 11 round-ups 11 would last several days. Quilting was another example of combining work with fun. The womenfolk would gather together for a day, and exchange patterns and gossip. Corn-shucking was yet another example of an enjoyable social event or gathering that had a practical purpose. The young adults were the ones that usually got involved in this. Whoever found a red ear of corn could kiss the person of his choice. So you can see that their attitude towards shucking corn was probably one of enthusiasm. Not all social gatherings revolved around work, however. Music-making was done purely for fun. Sam Sutton, who has been blind most of his life, used to play the banjo. He states - and with considerable pride - that he used to be able to play the banjo all night long and never play the same tune twice. So the mountain people were not as serious and stoical as some would have them be - they had their fun too. It is unclear to us as to when the first organized public school carne into existence in the Ca taloochee area. It \vas probably in the late 1860's or 1870's. So how was the problem of educating the people of the area approached before this time? The people of Cataloochee were too poor and too far removed from "civilizatiori " to send their children to the schools of the lay readers, so the apprenticeship system sprang into existence. This system was established by law and was supported in part by taxation. 5 The apprenticeship system called for the appointment of overseers of the poor. At first, these overseers had to raise by taxation, or otherwise, sums of money with \¥hich to buy hemp, or flax, or wool to be used in teaching the children a trade. Boys were apprenticed until they were twenty-four years old, and girls until they were twenty-one, or until they got married. Later the overseers were charged by law to teach these children the Bible and the truths of the Christian religion. They were also obligated to teach the ''rudiments of learningn - that is the Three R's. 3 Even though the people of Haywood County passed a bill in 1839 creating public schools, or "free schools," this new development in education was s lovl to re<::.ch Ca ta loochee. When the "free schools" did finally reach Cataloochee, they were usually one-room affairs constructed from logs and hand sawed lumber. Nost time there was a large fireplace at one end where hickory logs were used for heat. At the school on Caldwell Fork, "Blind Sam Sutton" used to have the responsibility of going tb the school early in the morning and starting the fire in the fireplace. These schools only covered the elementary years, first through eighth grades, and students were classified according to age and previous schooling. School lasted for only five months at a time, and since the months of school revolved around the cycle of the crops, a boy or girl might be twenty-one before his education wa s c omp l ete d . Friday was a big day at the school. Spelling bees were held Friday mornings with public speaking, or "speech-makin'" coming after. Students had to memorize verse from a book, or write their own, and recite to the whole class. Besides the three R"s, other subjects that were touched upon were history and literature. The school masters were usually paid with produce grown on the mountain farm. The teachers were generally "untrained" 6 in our sense of the word. Glen Palmer who taught at Indian Creek School only possessed a high school education. 4 There were several factors of the Cataloochee environment that would have seemingly produced a general attitude of casual indifference towards education. The school terms, and the resulting attendance depended upon weather and crop conditions. The essence of life in the Cataloochee area, and in the mountains in general, was farming. The children, in this sense, became an important labor force when planting and harvesting time came around. Some of the children lived quite a distance from the school, and the state of the roads, bridges and foot logs was such as to prevent regular attendance. Moreover, many of the parents of these children were extremely limited in their formal education. 5 But the attitude of the people towards education was more serious than the above conditions would lead one to believe. A case in point is how the Indian Creek School came to be established. One of the schools in Big Cataloochee was apparently 7 in poor condition so some leading men o£ the area "Turkey George" Palmer, "Uncle" Steve ~voody and one other - decided to ' '-.___./ go to the county seat at Waynesville and secure approval for a new school. Officials in Waynesville, howev~r, turned down the proposal due to a shortage of funds - even though the three men had offered to supply lumber and labor if the county would just furnish the nails. Thereafter, "Turkey George" et al decided to force the county to take issue with the problem; so one night after sharing a toast or two of moonshine, the three men burned down the school. Haywood County responded as expected, and built the Indian Creek School, which still stands today. For the 1931-1932 school term, just as the Park was moving 1n, the school in Little Cataloochee had fifteen students with one teacher; the Indian Creek School in Big Cataloochee had thirty-seven students with two teachers; and there was no school on Caldwell Fork at all. A lot for the first church in Cataloochee was donated by Julia Pdlmer in 1858 to George Palmer, Y. Bennett and Levi Cald-well. This became the Palmer Chapel as it was commonly known. We have reason to believe that people of Cataloochee, prior to this time, merely met in someone's cabin or out in the open spaces for religious gatherings. In 1889 Little Cataloochee Baptist Church was erected. There were no "preachers-in-residence'' at these churches; circuit-riders would come through the area once or twice a month. 8 Church services were not merely religious in nature, at least not from the peoples' point of view. They were also social gatherings - a place where people could mix with friends and neighbors and talk awhile. During these services there was a good deal of running in and out of the church by the men and boys. They would congregate outside and whittle, gossip, drive bargains, and debate among themselves some point of dogma. Big Creek and Caldwell Fork Valley ~ettlements, that were adjacent to Little and Big Cataloochee respectively, had no churches at all. Wlyce McGaha, who grew up on Big Creek, but later moved to Little Cataloochee, did not hear a preacher until he was twenty-one years old. In Big Creek the people reverted to the time before churches were built; someone's home was used as a meeting place, and after the children were "put on the go, 11 the grown-ups \vould sit around and informally discuss religion. 6 The people of Cataloochee usually respected the Sabbath. There was no hunting or firing of guns that day; even moonshining was stopped for Sunday. The people were simple and conservative in their approach to religion, but they were not the 11 firebreathers11 that many people believed them to be. Johnathan Woody, who grew up on Big Cataloochee and who later became the President of the First National Bank in Waynesville, would have us believe that the people of Cataloochee were "very strict religious." ) 9 Furthermore, he contends that there v1as a general lack of moonshining in the area because of the religious convictions of the people. He is failing to see that if there is a connection between moonshing and the religious beliefs of the people, it is only a very slight one, and that moonshining was indulged in primarily for economic reasons. If a man had a large family and most of them were, and if he could get four to five times more money per bushel of corn by distilling it - then why shouldn't he make his own liquor. In general, the attitudes toward religion and education, whether organized or not, were tempered-by external forces: the isolation of the community and the econo~ic realities of mountain life. True - the education of these mountain people was limited whether they attended the "free schools" or not. That they v1ere able to adapt their lives to the contours of their environment is a type of education not often considered. Were the people of Cataloochee in the 1920's as fiercely independent as their predecessors? Not at all. Inter-dependence for economic and social reasons had been a reality for quite some time, and the tide of urbanization was beginning to move in, i.e., the Sears a nd Roebuck catalog. But these people had learned their lessons well from their pioneer ancestors; that to survive in the mountains, you must adapt to the realities of your environment. l Footnotes 1. W. C. Allen, The Annals of Haywood County .-(1935), p. 195. 2. John C. Campbell, The Southern Highlander and nis Horne-land (University Press of Kentucky, 1921), p. 268. 3. Horace Kephart, Our Southern Highlanders (Macmillan Co., 1921), p. 262. 4. Henry McGilbert Mason, "The Memoir of a Southern Appala-chian Mountaineer," unpublished. 5. Wylce McGaha, Interview, (Maggie Valley, N.C., April 12, 1973). 6. W. Clark Medford, The Middle History of Haywood County {Miller Printing Co., 1968), pp. 59-60. 10 .l '-/ Bibliography Allen, W. c. The Annals of Haywood County, 1935. Campbell, John C. Tne Southern Highlander and his Homeland. w (Lexington, Ky.: Un1versity Press of Kentucky), 1921. Kephart, Horace. Our Southern Highlanders. millan Co.), 1921. (New York: Mac- !1ason, Henry McGi lbert. "The Memoir c f a Southern Appalachian." Unpublished. McGaha, \'Vylce. Interview (Maggie Valley, N.C.), April 12, 1973. Medford, Clark. The Middle History of Haywood County. ville, N.C.: Miller Printing Co~, 1968. (Waynes- Sutton, Sam. Interview (Maggie Valley, N.C.), April 18, 1973. Woody, Johnathan. Interview (\'laynesville, N.C.), March 10, 1973. 11