Western Carolina University (20)

View all

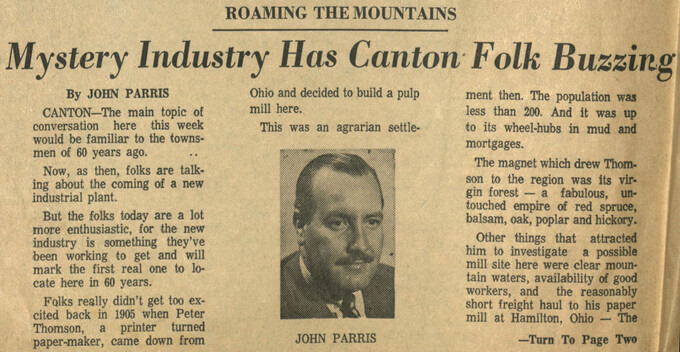

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2683)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (15)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Champion Fibre Company (5)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (23)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (17)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Stearns, I. K. (2)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (45)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (55)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (72)

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (0)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (0)

- Brasstown Carvers (0)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (0)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (0)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (0)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (0)

- Cherokee Language Program (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Crowe, Amanda (0)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (0)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (0)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (0)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (0)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (0)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (0)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (0)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (0)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (0)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (0)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (0)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (0)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Roberts, Vivienne (0)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (0)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (0)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (0)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (0)

- USFS (0)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (0)

- Western Carolina College (0)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (0)

- Western Carolina University (0)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (0)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (0)

- Williams, Isadora (0)

- 1810s (1)

- 1840s (1)

- 1850s (2)

- 1860s (3)

- 1870s (4)

- 1880s (7)

- 1890s (64)

- 1900s (294)

- 1910s (227)

- 1920s (461)

- 1930s (1501)

- 1940s (82)

- 1950s (15)

- 1960s (13)

- 1970s (47)

- 1980s (14)

- 1990s (17)

- 2000s (31)

- 2010s (1)

- 1600s (0)

- 1700s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 2020s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (80)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1)

- Avery County (N.C.) (6)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (145)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (204)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (10)

- Clay County (N.C.) (3)

- Graham County (N.C.) (108)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (416)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (263)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (13)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (58)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (17)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (8)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (25)

- Madison County (N.C.) (14)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (5)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (7)

- Polk County (N.C.) (2)

- Qualla Boundary (22)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (16)

- Swain County (N.C.) (513)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (36)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (2)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (34)

- Aerial Views (3)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (4)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (77)

- Drawings (visual Works) (174)

- Envelopes (2)

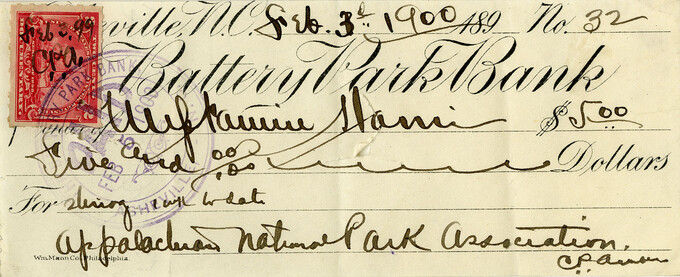

- Financial Records (9)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (34)

- Guidebooks (1)

- Interviews (11)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (219)

- Manuscripts (documents) (91)

- Maps (documents) (69)

- Memorandums (14)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (20)

- Negatives (photographs) (198)

- Newsletters (12)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Photographs (1657)

- Portraits (37)

- Postcards (15)

- Publications (documents) (107)

- Scrapbooks (3)

- Sound Recordings (7)

- Speeches (documents) (11)

- Transcripts (46)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Personal Narratives (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (198)

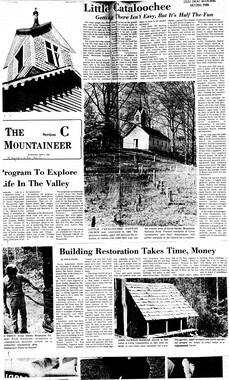

- Cataloochee History Project (65)

- George Masa Collection (89)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (126)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Jim Thompson Collection (44)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Map Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (10)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (107)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (0)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Appalachian Trail (19)

- Church buildings (9)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (91)

- Dams (20)

- Floods (1)

- Forest conservation (11)

- Forests and forestry (42)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (64)

- Hunting (2)

- Logging (25)

- Maps (74)

- North Carolina -- Maps (5)

- Postcards (15)

- Railroad trains (8)

- Sports (4)

- Storytelling (2)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (39)

- African Americans (0)

- Artisans (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Cherokee pottery (0)

- Cherokee women (0)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (0)

- Dance (0)

- Education (0)

- Folk music (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Mines and mineral resources (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- School integration -- Southern States (0)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- Slavery (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- World War, 1939-1945 (0)

- Sound (7)

- StillImage (2088)

- Text (655)

- MovingImage (0)

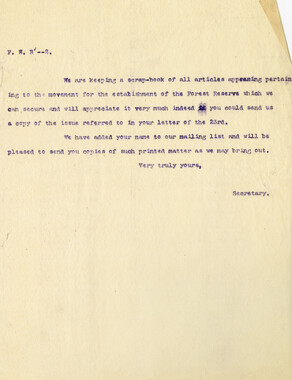

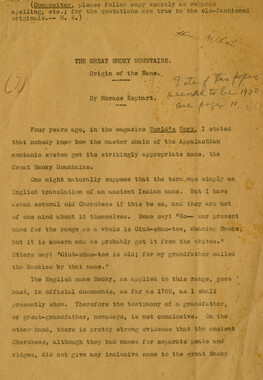

Kephart writes of odd names in the Smoky Mountains

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

KEPHART WRITES x A JL. TAINS Every. Mountain, Creek, Branch, Cove.and "Lead" Has Name Known Only .To Few Adventurers This Is ths first of a series of Sunday articles, written especially for The X'lmes by Horace Kephart, of Bryson City, noted author and authority on the Great Smoky Mountains, on subjects of great Interest relating to the Great Smokies. This story on "Odd Names in the Smoky Mountains" will be followed next Sunday by "Panthers In the Great Smoky Mountains" and the following Sunday by "The Language of the Cherokees."-—Editor. !X. By HORACE KEPHART WHEN I first came into the Carolina mountains I had no guide but an old "tope sheet" atlas of the TJ. S. Geological Survey. In poring over those maps my eyes were caught and held by many queer names that amused or puzzled me. I could grasp the significance yK.-.,„.-,.. of Standing Indian, as applied to a mountain—the term was picturesque and dignified—but what quirk of Imagination, what ribald streak of humor, had dubbed a fine summit of the Blue Ridge with such a name as Chunky Gal? Nor was my wonder much abated when I learned, from the Indians, that Chunky Gal is the white mountaineer's delicate way of interpreting the original Cherokee name, which means Pregnant Woman. On the way up Shooting Creek to the Chunky Gal, one goes parallel with Drowning Creek and passes Lick- log Branch, Jack Rabbit Mountain, Fleaback Mountain, Hothouse Branch, Pounding Creek, Burnt Cabin and Thumping Creek, all in the course of ten miles. As I had never seen or heard of a Horace Kephart "bald" mountain, in the sense of a heavily wooded dome topped by an unaccountable open meadow of wild bluegrass, such names on the map as Parson Bald and Warrior Ba'.d (properly Wayah, meaning wolf) caused me to break out laughing. I thought they were inversions of Bald Parson and Bald Warrior. But when I came upon Burning-town Bald and Wlne- spring Bald I was quite confused. What, in the name of sanity, could such names mean? Jitter, when I went to live far back in the wilderness, not in the Blue Ridge but in the Great Smoky Mountains, where no map showed accurately the features or the names of that rugged country, I had to learn everything, from the ground up, by my own exploring and from the lips of the few pioneers who had ventured there. The settlements, such as they were, extended in a fringe of scattered cabins along the southern border of the Smokies, and along their northern border in Tennessee. The great mass of the Smokies was quite uninhabited, as most of it still is today. Often, in that wilderness, while, going on my lone exploring trips, I met no human being for several days, nor saw any sign of man save here and there a foot-trail left by wandering hunters or fishermen, or herdsmen who came into the high ranges, now and then, to look after their half-wild cattle and razorbacks. Vividly Descriptive And still, every creek and branch and "lead" and gap, west of Cling- man Dome, had a name by which it was known to the few adventurers who quested the woods. • And such names! Vividly descriptive, if one understood the backwoods lin^o; often unintellible if he did not. Whimsical names. Sometimes profane or indecent' names—but with good cause, as one realized when he tried to bore his way through the laurel "slicks" or found himself trapped in a gulch where the only way out was by edging along cliiis and perilously sliding down the slippery, precipitous courses of mountain torrents. To be caught there in fog, that is to say, in clouds, when one could not see a tree ten feet away, was a dismal predicament indeed; or when steady rain set in and the drench bushes rubbed the water right through the duxbak, leather, or any other material that one could wear in mountain climbing. No wonder we have such names in the Smokies as Ripshin and the "Harricane," the Devil's Den and Huggin's Hell, the Defeat and Desolation branches of Bone Valley, the Rough Arm and the Slowdown, Tear Breeches and Long Hungry Ridge. Aye, worse names, that mav not be put in print until some stripling of the intelligentsia comes from a big city and whoops over his discovery of some new and bizarre specimen of smut. Names there are, in plenty, that express the raw virility of the backwoodsman, his Uteral-mlndedness, his whimsical humor that makes a sport of hardship and privation. Picturts, showing in a word or two, the features of places, or celebrating some incident of the rough life of the woods, or recalling some person who one time was somehow identified with a given place. On the watersheds of Twenty Mils and Eagle Creek are Judy Branch and Genes Camp Branch, Big Tommy and Little Tommy, the Shuck- stack, Big Swag Ridge, Proctor's Sang Branch (ginseng), Lawson Sant-lot Branch (once a cattle cored). Painter (panther) Branch, Bear Pen (a log trap), Coon-town Branch, Pawpaw and Soapstona, Pinnacle Creek. In Hazel Creek Country In the Hazel Creek country we have Blockhouse and Thunderhead mountains. Brier Knob. Indian Camp, Woolly Ridge, the chestnut Bald, the Raven's Den, Owl Cove, Old House Branch, Slick Rock. When one turns up from Bone Valley to the Locust Gap he comes to the Nigh Long Big Slats Branch, then to the Main Long Big Fiats Branch, beyond which, as a head stream, is the Fur Long Big Flats Branch.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

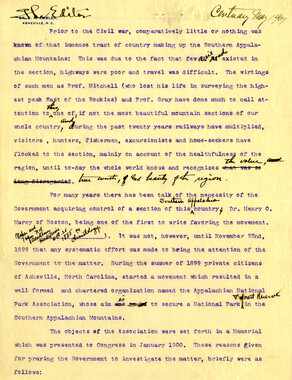

This undated article is by Horace Kephart (1862-1931), a noted naturalist, woodsman, journalist, and author. In 1904, he left his work as a librarian in St. Louis and permanently moved to western North Carolina. His popular book, “Camping and Woodcraft” was first published 1906; the 1916/1917 edition is considered a standard manual for campers after almost a century of use. Living and working in a cabin on Hazel Creek in Swain County, Kephart began to document life in the Great Smoky Mountains, producing “Our Southern Highlanders” in 1913. Throughout his life, Kephart wrote many articles supporting the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

-

.jpg)