Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (24)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6772)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (1)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (65)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (12)

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association (0)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (0)

- Berry, Walter (0)

- Brasstown Carvers (0)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (0)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (0)

- Champion Fibre Company (0)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Crowe, Amanda (0)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (0)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (0)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (0)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (0)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (0)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (0)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (0)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (0)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (0)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (0)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (0)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (0)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (0)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (0)

- North Carolina Park Commission (0)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (0)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (0)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (0)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (0)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (0)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (0)

- Stearns, I. K. (0)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (0)

- USFS (0)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (0)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (0)

- Western Carolina College (0)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (0)

- Western Carolina University (0)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (0)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (0)

- Williams, Isadora (0)

- 1800s (2)

- 1890s (6)

- 1900s (7)

- 1910s (1)

- 1920s (3)

- 1930s (13)

- 1940s (37)

- 1950s (12)

- 1960s (7)

- 1970s (38)

- 1980s (11)

- 1990s (2)

- 2000s (3)

- 2010s (38)

- 1600s (0)

- 1700s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1860s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 2020s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (256)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (2)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (1)

- Qualla Boundary (285)

- Asheville (N.C.) (0)

- Avery County (N.C.) (0)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (0)

- Clay County (N.C.) (0)

- Graham County (N.C.) (0)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (0)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (0)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Macon County (N.C.) (0)

- Madison County (N.C.) (0)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (0)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (0)

- Polk County (N.C.) (0)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (0)

- Swain County (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (0)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (0)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (3)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (3)

- Interviews (12)

- Newsletters (1)

- Photographs (208)

- Poetry (2)

- Publications (documents) (46)

- Sound Recordings (22)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (12)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Manuscripts (documents) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Personal Narratives (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Transcripts (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

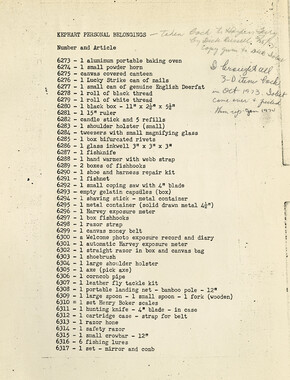

- Horace Kephart Collection (1)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

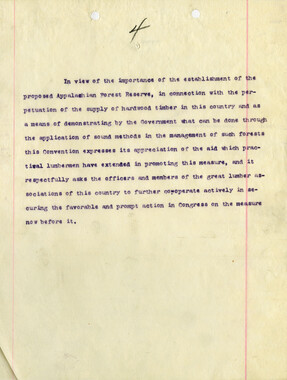

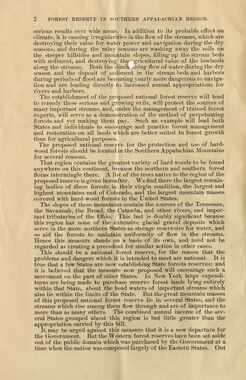

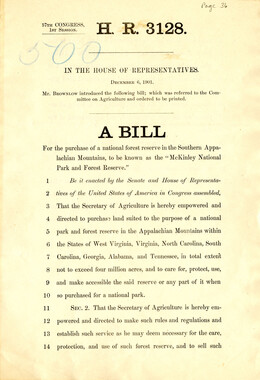

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (0)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- Artisans (125)

- Cherokee art (18)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (27)

- Cherokee women (140)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (1)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (1)

- Storytelling (5)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (1)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (14)

- African Americans (0)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Education (0)

- Floods (0)

- Folk music (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Hunting (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- Mines and mineral resources (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- School integration -- Southern States (0)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- Slavery (0)

- Sports (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- World War, 1939-1945 (0)

Kathi Littlejohn: Cherokee Storyteller

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

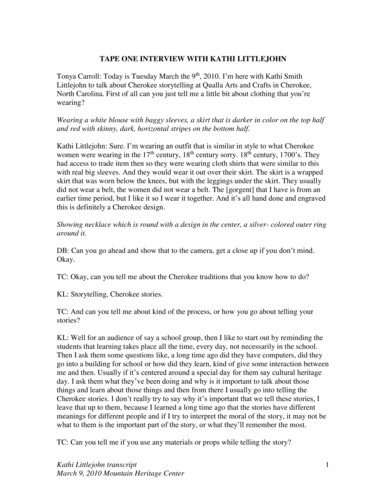

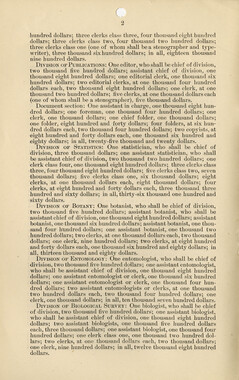

Kathi Littlejohn transcript March 9, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 1 TAPE ONE INTERVIEW WITH KATHI LITTLEJOHN Tonya Carroll: Today is Tuesday March the 9th, 2010. I’m here with Kathi Smith Littlejohn to talk about Cherokee storytelling at Qualla Arts and Crafts in Cherokee, North Carolina. First of all can you just tell me a little bit about clothing that you’re wearing? Wearing a white blouse with baggy sleeves, a skirt that is darker in color on the top half and red with skinny, dark, horizontal stripes on the bottom half. Kathi Littlejohn: Sure. I’m wearing an outfit that is similar in style to what Cherokee women were wearing in the 17th century, 18th century sorry. 18th century, 1700’s. They had access to trade item then so they were wearing cloth shirts that were similar to this with real big sleeves. And they would wear it out over their skirt. The skirt is a wrapped skirt that was worn below the knees, but with the leggings under the skirt. They usually did not wear a belt, the women did not wear a belt. The [gorgent] that I have is from an earlier time period, but I like it so I wear it together. And it’s all hand done and engraved this is definitely a Cherokee design. Showing necklace which is round with a design in the center, a silver- colored outer ring around it. DB: Can you go ahead and show that to the camera, get a close up if you don’t mind. Okay. TC: Okay, can you tell me about the Cherokee traditions that you know how to do? KL: Storytelling, Cherokee stories. TC: And can you tell me about kind of the process, or how you go about telling your stories? KL: Well for an audience of say a school group, then I like to start out by reminding the students that learning takes place all the time, every day, not necessarily in the school. Then I ask them some questions like, a long time ago did they have computers, did they go into a building for school or how did they learn, kind of give some interaction between me and then. Usually if it’s centered around a special day for them say cultural heritage day. I ask them what they’ve been doing and why is it important to talk about those things and learn about those things and then from there I usually go into telling the Cherokee stories. I don’t really try to say why it’s important that we tell these stories, I leave that up to them, because I learned a long time ago that the stories have different meanings for different people and if I try to interpret the moral of the story, it may not be what to them is the important part of the story, or what they’ll remember the most. TC: Can you tell me if you use any materials or props while telling the story? Kathi Littlejohn transcript March 9, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 2 KL: It depends, I usually do not. I’ve found that the stories and people’s imaginations are enough. But if it’s a large class or if there’s several classes put together I usually have a longer time with them. So that they don’t get so restless, it depends on the age group too, I usually take some things and we talk about things. Like I try to take another skirt and some leggings and I call up some of the students and have them try them on and put them on, we talk about them and some things. They like to touch things. So they’re not necessarily a part of the stories, but sometime I take kind of show and tell items so that they can feel them and hold them. TC: Have the stories that you tell always been told by the Cherokee? KL: Yes, yes, since time began. TC: Can you kind of say that with a question in it? KL: No! What? TC: When they edit, my question is not going to be on there, so if you just say yes, then. KL: Oh TC: And the question was have the stores you tell always been told by the Cherokee? KL: Yes, the stories that I tell are all Cherokee stories and there is no way to say oh this story was being told in 1920, because the stories are old, they’ve been telling these, Cherokee people have told these stories since time began. TC: How did you learn the art of storytelling? KL: I think it’s just a way of expression that I’ve picked up from my mother and from older people that I worked with. Not so much the storytelling, but the way of expressing yourself, myself, not yourself, myself. I think I learned from their enthusiasm and the way that they could describe something. I think I picked that up from them. TC: You talked about how you learned how to express yourself by the older people that you worked with, and where did you work and who were those people? KL: I worked at the Oconaluftee Indian Village, when I was 14 until I was 19, I worked there every summer. And I was hired as a tour guide. In between tours on slow days, especially during bad weather, then we would sit around and tell stories and they would tell me different stories of when they were younger, and funny stories about their life, or stories that they have heard when they were children. TC: Why did you become interested in telling Cherokee stories? Kathi Littlejohn transcript March 9, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 3 KL: Well I guess like most people who start doing traditions you just never wake up one day and say I think I’m going to make a basket, or I think I’m going to start telling Cherokee stories. What happened to me was I was taking a class and it was in children’s literacy. And our teacher gave us an assignment that we had to learn how to use flannel board, and flannel board characters, we had to make them. And then we had to tell the class our story and use the flannel board figures. So I chose a Cherokee story that I knew and cut out the figures and made them and to my surprise after I was through, the other people in my class, who were teachers in different schools, different educational settings, asked me to come and tell stories in their classroom. I never once thought to do that on my own. So once I started going to their classrooms I began learning a lot more stories, and didn’t ever use the flannel board but just started telling stories, and that’s how I started. TC: About how old were you when that happened? KL: I was in my 20’s. Probably mid 20’s. TC: When you were trying to learn more Cherokee stories, did you ask a person to teach you? KL: No, I didn’t. I started trying to find stories that were written. I even got a grant that allowed me to go to Washington D.C. and I got some of the Cherokee stories out of the Smithsonian archives. Then I tried to find them in different books. I never asked anybody because at that time there was only one person that I knew of that was actually telling Cherokee stories and I listened to her, Mrs. Chiltosky, but I never asked her to teach or where did she get the stories from. I just started trying to gather them on my own. And after awhile, although I got a lot of stories that way. People started coming up to me after I finished telling the stories, or sometimes not even telling stories and asking me did I know this story. Or they would just start telling me that their grandfather had told them this story, and I tried to write those down and gather them that way. TC: Do you remember when you were in school, did you learn or hear any Cherokee stories then? KL: No, no I never did. TC: I kind of have an idea, but how long have you been telling Cherokee stories? KL: More than 20 years. TC: Have you or are you passing the tradition of Cherokee storytelling to the younger generation? KL: I am, but not in a way that I have a person or a group of people that I routinely meet with and give them home work or give them assignments, or we work on something together. The way that I have is classes that have heard me tell stories, take the stories Kathi Littlejohn transcript March 9, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 4 and they turn them into art projects and I’ve seen a lot of those. Classes that have heard me, they’ll go back to their classroom and their teacher will say now everyone write Mrs. Littlejohn a thank you. And a lot of them will illustrate their favorite story that they heard me tell and put that in the thank you card, which is really nice. Lots of times I’ve heard of different other projects that students have done. That they’ve done a play, or they’ve invited me to come see a play. They’ve even performed before the show up at the drama and they’ll do Cherokee legends. They invited me to come to the youth center when the casino hotel was being built because the youth center children got to illustrate a legend using tile. And they chose two different legends. So I got to participate in that. So a group of children learned those two legends for that project. So it’s a lot of different ways that I know that I’ve helped pass that along. And the Miss Cherokees, the different girls that are running for the different royalty titles will call me and ask for help with a particular legend because they want to use that. They want to showcase their speaking ability and their talent portion of the competition or the pageants that they want to do a Cherokee legend. So I think that’s another way that I’ve helped pass it on. TC: Do you have any tapes or cd’s of you telling your stories? KL: I have two tapes, there are two tapes that have been published that are now really out of date because nobody has cassette tape players anymore. They all have cd’s and dvd’s and flash drives and things like that. So I’m in the process of getting a cd finished. I’ve had a number of stories recorded so we’re in the process of getting that developed. TC: How have you noticed Cherokee storytelling change over time? KL: More people know them, more people use them in their art, the other day someone asked me if I could give them some copies of some stories because they wanted to make little figures, little dolls to sell based on the characters in the stories. So I see people using them more in their artwork and I see more I guess that’s all. Well I see teachers and students use them more in school. TC: Earlier when you said when you first started in researching and learning the Cherokee stories you knew only one other person that was actually telling the stories. Are there more people that are doing that now? KL: There are more people who are telling stories, I wish there was lots more. I can think of, from that one person, I guess I can think of probably five, six, including myself. That’s not to say that Cherokee stories aren’t told in the home setting by lots and lots of people, but in a more organized with an audience and then the public, I can think of five or six. TC: Can you describe to me how you felt the first time that you heard somebody telling a Cherokee story? KL: Oh I was fascinated I loved that. How I felt? Kathi Littlejohn transcript March 9, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 5 TC: I mean tell me like, do you remember where you were, who you were with, who was telling the story, what story it was? KL: I don’t remember what story it was, but I remember it was being at the Village, and I can remember the lady that was telling the story. She was really funny, so I’m sure that she was telling a really funny story, and it just made an impression on me. TC: How did you feel the first time that you told Cherokee stories in front of an audience? KL: How did I feel, I was really nervous. [laugh] I was afraid that someone would say, well that’s not right that’s not the way the story goes. [laugh] But I was and I was proud, I was really proud that I was able to bring them to life. TC: Why is it important to keep Cherokee storytelling alive? KL: Well I’ve thought about that a lot because storytelling is not as common as it used to be. And I think sometimes why am I doing this. Or why is it important that more people learn to tell stories. And I guess it’s the best way that I can make it understood is something that someone else said. I wish I could tell you who that person was, but it goes like this. When the legends die, the dreams end and when the dreams end, there is no more greatness. So to me that sums it up. We have to keep them alive. TC: Can you, tell me a little about the importance or the meaning behind, originally why the Cherokees would have these stories? KL: A lot of tribes had storytellers and storytelling as a really sacred story or legend and even with rules like once they begin they can’t stop until the story is finished no matter how long it takes. Or that you don’t tell them unless it’s wintertime, so there are rules like that. What was the question? TC: Originally why did the Cherokee have these stories? KL: Or that they could only tell them at certain times of the year, different seasons. The Cherokee have always been able to tell the stories at any time and anyone could tell them because they…we use them more as teaching lessons in every day life. If someone was behaving badly they were jealous or greedy or selfish or lazy then someone would say, or remind them of the story of say the possum or the rabbit who had done the same thing. And everyone would understand that they were saying don’t be like that character, don’t be like the rabbit, start acting better. TC: Did the Cherokee use stories maybe to keep track and you know of historic events or other, besides just the lesson telling like the different games? Kathi Littlejohn transcript March 9, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 6 KL: Yes. There are several legends that are around the game which lets me know, or I think I know that that game was really important, that it was a major part of everyone’s lives. TC: When did you realize, or have you realized that you are a Cherokee tradition bearer because you tell the Cherokee stories? KL: I never thought of myself that way. I don’t think of myself that way. But I realize or I’m beginning to realize that in all the 20 years that I’ve been telling stories, there’s only been 3 or 4 other people. They were telling stories about the same amount of time, there’s not very many new storytellers, or I should say, younger storytellers that are beginning to pick this up and also do that. I guess that’s when I realized that I am a tradition keeper and that perhaps instead of telling them, telling the stories, I need to put more energy into fostering a relationship with someone else that can pick up the tradition and go with it. TC: How did it make you feel that people in the Cherokee community consider you a tradition bearer? KL: Very proud. I’m very proud of that. It’s a real honor to me to be at Food Lion, or the ballgame or the post office and children come up to me and say, I know you, I remember when you came and told us the legend of so and so and they’ll talk about that. That makes me very proud. TC: Are you worried that Cherokee storytelling might be dying down? KL: Yes, I’m very worried, and I’ve been thinking a lot of the best way to create some type of structure or foundation, or avenue, whatever you want to call it will reach out to people who may not even think of themselves as a storyteller. Because I never did but to really encourage people and have them come take part in learning. I think that’s incredibly important. TC: What is your favorite Cherokee story to tell? KL: I don't have a favorite, they are all my favorites, but the one that I get the most request for is Spearfinger I don’t care how many times they hear it, that is everyone’s favorite. I can walk into a classroom, I won’t even take my coat off and the students are saying Spearfinger, Spearfinger tell Spearfinger. So I guess that’s everyone’s favorite. But mine, are all of them. TC: Do you have any information that you would like to add? KL: No. [laugh] TC: Do you make any other Cherokee crafts or carry on other Cherokee traditions? Kathi Littlejohn transcript March 9, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 7 KL: No. I can’t say that I can make anything else. I’m trying to learn feather cape making. I just recently took a class in that. Where that goes I don’t know, I don’t know if I’ll be able to make anything or not. I think what I, and I’ve said before that I’ve been trying to think of ways to focus my energy and time and efforts into developing a way that people can learn the stories and become storytellers. So instead of learning to make something I’m struggling to find ways to perpetuate the storytelling. TC: So if I came to you and I said Kathi I want to learn how to tell Cherokee stories, what would you tell me? KL: I would tell you that I will spend as much time with you as you can. I will tell you that I will meet with you anytime, anywhere, and I will try to give you all of the resources that I have and I would have you just start telling. Even if you don’t know all of it, even if you think you should be more experienced, just start telling. I would encourage you to do that. I would take you with me to my next storytelling even and I would encourage you to tell a story at that event. I would do anything I could to get you to stay interested and to learn as much as you could. TC: If somebody came up to you and said, story Cherokee storytelling all it is, is just memorizing a story and just repeating it, what would you tell them? KL: Well I would try to think of a nice way to tell them that they were really wrong. [laugh] I would invite them to go with me to a students’ classroom, no matter how old and watch their faces when they listen. Because it’s not just the story, it’s their imagination, they can see it, they can feel it and it’s you can see it on their faces. It’s not just memorizing. TC: I don’t know if you've thought about it, but do you know we’re going to ask you to share some of your storytelling with us, have you thought of the one that you want to tell. KL: Sure. I yes I have, I thought of the games, the ones about games, that was interesting to me, I never stopped to think which stories had to do with games, so I thought I would tell two of those. TC: Okay, should she just go ahead David Brewin: I don’t know, I think we ought to change tapes. I just wanted to ask you something I used to be a storyteller myself. KL: Oh did you really? DB: And I told Jack tales. KL: Yes Kathi Littlejohn transcript March 9, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 8 DB: And do you find that you know regardless of what culture you’re telling it whether they are Cherokee or non Cherokee that the stores kind of transcend whatever, whoever you are. KL: Yes, I find that, I find that, and what’s been a real surprise to me is how similar some of the stories are, or how people own the stories. There was a class at Western and they invited me to come up and they asked me in particular to tell a creation story. They had gotten a book and it was of an African story on how the world was made, so they put all their creation stories together, and everybody had the exact same response, that they all wanted to tell each other, that’s not the way the world was made, this is how the world was made and I thought that was really interesting that even if it was the book of Genesis or the one from Africa about a spider creating the world, that every one of them thought theirs was really the way that the world was made. Including me. [laugh] DB: I was I don’t know if you ever got this reaction, I used to go to go the schools, and they used to say here’s Mr. Brewin he’s going to tell stories and they’d say, stories ewww and then you’d tell the stories and I couldn’t get out of there. KL: You could not be quiet they wanted you to go on, more and more and more and more. DB: Which I find encouraging because people just spend, you think kids just spend all their time looking at TV, but they really want to use their imaginations. KL: They really do, they really do. And I’ve never, I’ve had teachers march in kids and say you sit right here, they had just acted up in the hall. Or they’ll say things like now you better watch out for so and so, they’re having a really bad day, if he gets out of hand you just signal me, but once you start telling those stories I have never had any, even high school they have never acted up because they just get so absorbed into this story. So you’re right. DB: It’s kind of a new experience for them to actually just use their imagination. KL: That’s kind of sad isn’t it, it’s really sad. DB: Do you have anything else you want to add to this Tonya? TC: No just hear the stories. DB: Well I’m going to change tapes, try to get a different. Tell you what Tonya, if you’d sit down, well let me just turn this off. END OF TAPE ONE KATHI LITTLEJOHN INTERVIEW Kathi Littlejohn transcript March 9, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 9 START OF TAPE TWO KATHI LITTLEJOHN INTERVIEW Kathi Littlejohn: Many years ago there was a Cherokee village near here, and there was a group of boys that loved to play Chunky. Now Chunky was a traditional Cherokee game that boys and girls played and it was a lot of fun, and it’s a game of skill as well as a game of guessing and estimating. For they would take a round rock a smooth rock and they would roll it and then they would throw pointed sticks at where they thought the rock would fall over. The one closest to that would win the game. And this particular group of boys played it all day long. They played it from the time they got up until the time it was too dark to see. And after awhile it got to where they wouldn’t help anyone do anything. Their mother’s would say, no don’t play today, I need you to help me do this. No I don’t want you to do that I need you to do this. No you played yesterday, come and help me do this. And they wouldn’t do it. They disobeyed them and they played all day long they would go in at night and they were so hungry. They played so much they didn’t even eat. They were starving. So at the end of the day, in the dark, they would demand that they would have supper. They wanted something to eat right then. Well the mom’s got to thinking about this and they didn’t like the way that they were behaving. So they all got together and that night when the boys came rushing in, they were so hungry and they wanted to eat. They said here, here’s your supper and they gave them a bowl of rocks. And when the boys said what is this. They said you want to play with rocks so much, that’s your super, you can eat those rocks. Oh the boys were so mad, they were so upset, they ran out into the middle of the village and they joined hands and they started to dance and they danced so fast they started rising in the air. Well this scared everyone and they started grabbing at them and trying to stop them from dancing and they were going so fast that they got all the way above their heads And finally the tallest man reached up and managed to grab one of the boys by the foot and jerked him and when he jerked him so hard he was swallowed up by the earth. And the other six kept going all the way up into the sky until they became part of the stars. Even today when you look up you’ll see a circle of six, and in English they call that the Pleiades but in Cherokee it’s the six dancing boys. Now the seventh boys that was covered into the dirt, his family cried so much over where he was buried that their tears watered the grave and a little tree started to grow. And it grew real tall and real straight and even today the pine trees have a point like no other tree, because the little boy is still pointing skyward to his friends where they’re dancing. DB: Great story. KL: [laugh] So you want another one? DB: Oh yeah. KL: Oh I know, cause you are going to have it here. Kathi Littlejohn transcript March 9, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 10 There was once a Cherokee girl named Mailee and every day Mailee’s job was to go and gather all the water for the day that her family would use. They gave Mailee a tightly woven basket, just as tight as they could weave it together and she would hurry down and fill the basket and hurry back before it leaked out the bottom, for as tightly they could weave water would always come out the bottom. So as you can imagine this took Mailee all day because there was water to bath with, to drink, to cook with and she would go down to the creek and go back with the water. Well the boys of the village liked Mailee and they wanted her to like them. So they began to go along the path with her and try to get her to pay attention to them. Every day they would jump in front of her and they would make funny faces and they would tease her and Mailee just went straight down, got the water, straight back. Every day the boys would say, no today’s the day she’s gunna talk to me, she’s not talking to you, and they would hang upside down in the tree or whatever, throw rocks and Mailee never looked at them, she went straight to the water, got it and went straight back with her basket. One by one the boys go tired of this and they went on to do other things. But the mud dauber, the little mud dauber, he watched the boys and he really liked Mailey too and he wanted her to pay attention to him. So he began to follow her down to the water and he’d fly around her head and he’d buzz and one day she swatted at him. Awww this… she likes me she noticed me and he’d just buzz more, bzzzz bzzz bzzz. She really got mad and she walked over and she grabbed his little mud dauber house and threw it into the fire and said there, now you leave me alone. The mud dauber was really sad because she was right he had to leave her alone because he had to make another house for winter was coming, he needed a warm place to stay. The next day as she walked to the creek with her basket she glanced in the fire and instead of destroying the house, the house was in there just as perfect as it was when she threw it in. It was darker, but it was really hard and she picked it up and she thought, hmmm I thought I got rid of this. She walked down to the creek and threw it in the water. She got her basket of water and hurried back home. The next morning when she went down there was that house still in the water. And she picked it up, there wasn’t a crack in it. She couldn’t believe it. She went back and showed everyone and they thought about this and they began to experiment and make things, bowls and pots and then put them in the fire, get them good and hard and then they would scoop up water and that’s how the Cherokee people got the idea to make pottery, from Mailee and the mud dauber. DB: Oh what a great story. KL: Thank you. DB: Would you tell me my favorite? KL: Which one’s that? DB: I thought you'd guess. KL: Spearfinger. [laugh] Kathi Littlejohn transcript March 9, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 11 DB: Yes. [laugh] KL: [laugh] I should have known. I should have known. What time is it because I’ve got to get back to work. DB: Five after 1. You don’t have I don’t want to put you into. KL: I could tell it pretty fast I guess. Let’s see. There are monsters in the world and a long time ago, the most horrible monster of all was Spearfinger. Not only was she scary because she was so tall and strong, but she had a rock like skin that nothing could go through, nothing, not an arrow, not anything, nothing would penetrate her skin. People believed that you couldn’t kill her. But the scariest thing about Spearfinger was that she was a shape changer. You could go out and go fishing with your grandpa, Spearfinger would sneak up behind him and spear in his liver and pull it out and eat it bloody and raw and then she would become just like your grandfather and call you over. Everybody was afraid of Spearfinger. And one day not far from here a Cherokee village got word that Spearfinger was coming their way and they were panicked. Do we run, do we hide, what do we do. And they decided that the best defense was to try to trap her and maybe then all of everybody try to kill her. So they started digging, everybody, everybody went out and got big baskets and dug the dirt. They were going to make a big pit all the way around the village and then they hoped to camouflage it. Everybody was helping. One little boy was trying so hard, he’d pick up a big basket of dirt and drop it. Or he’d stumble over something and get in somebody’s way and finally his father said you’re in the way just get over there, if you can’t do better than that, just get out of the way. And that hurt his feeling so much, he just wanted to help. He went over and sat there and thought I just wanted to help look nobody’s fussing at that little boy. He was so upset that he didn’t begin to notice first that there was a bird that was caught in a vine and when he did without thinking he just let it go and helped it and was surprised when instead of flying away the bird began to talk. And said we birds know how to kill Spearfinger because we’re so small she doesn't fool with us and we watch her we know the best way to kill her is to shoot her through her heart. He said, well she doesn’t have a heart nobody knows where to kill her, or how to kill her, that’s why we’re doing this. They said no, we know, and the bird whispered the secret to him. He was so excited that he ran out and he was trying to get everybody’s attention and they heard her, she was coming, she was stomping and screaming with hunger and she was ravenously hungry and she got closer and closer and oh she stunk, the stench of her was awful. Dead, decaying flesh, blood, dried blood all over her razor sharp teeth and her finger, her long spear finger was caked with blood. She was waving it in the air and screaming and they were so scared. She fell into the pit and for a moment they were paralyzed because she started clawing her way out and at last they rushed to the edge and they threw everything they could at her. She would just catch it in the air and throw it back and she was getting closer and closer to the edge of the pit. And they started throwing spears and shooting bows and arrows and it just bounced off of her skin. She was laughing. She was almost going to get out to the top. And he ran over and told the best bowman that they had and he saw where the bird had said her heart was, for it was at the tip of her Spearfinger. It Kathi Littlejohn transcript March 9, 2010 Mountain Heritage Center 12 was tiny, tiny, smaller than a pea. And he drew back and took aim and shot her right through the heart and she died, and the little boy was a hero. DB: Thank you. KL: You’re welcome. [laugh] Well thank you both, TC: Thank you for coming. KL: You’re welcome. I hope it... END OF TAPE TWO KATHI LITTLEJOHN INTERVIEW

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

In this video, Kathi Littlejohn, Cherokee storyteller, transports listeners into tradition through a story of “Spearfinger.” Littlejohn’s stories pass on the heritage of the Cherokee people. The transcript provided is an unedited version of the video.

-