Western Carolina University (11)

View all

- Cherokee Traditions (3)

- Craft Revival (10)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (31)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (8)

- Journeys Through Jackson (48)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (4)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (20)

- Picturing Appalachia (4)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (38)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (10)

- Western Carolina University Publications (195)

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (0)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (0)

- Horace Kephart (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (0)

- Travel Western North Carolina (0)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (0)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (0)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (0)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (0)

University of North Carolina Asheville (0)

View all

- Faces of Asheville (0)

- Forestry in Western North Carolina (0)

- Grove Park Inn Photograph Collection (0)

- Isaiah Rice Photograph Collection (0)

- Morse Family Chimney Rock Park Collection (0)

- Picturing Asheville and Western North Carolina (0)

- North Carolina Park Commission (30)

- Western Carolina University (195)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (6)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (17)

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association (0)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (0)

- Berry, Walter (0)

- Brasstown Carvers (0)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (0)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (0)

- Champion Fibre Company (0)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (0)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (0)

- Cherokee Language Program (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Crowe, Amanda (0)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (0)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (0)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (0)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (0)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (0)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (0)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (0)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (0)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (0)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (0)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (0)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (0)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (0)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (0)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (0)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (0)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Roberts, Vivienne (0)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (0)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (0)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (0)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (0)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (0)

- Stearns, I. K. (0)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (0)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (0)

- USFS (0)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (0)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (0)

- Western Carolina College (0)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (0)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (0)

- Williams, Isadora (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (11)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (4)

- Graham County (N.C.) (1)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (33)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (288)

- Macon County (N.C.) (12)

- Qualla Boundary (9)

- Swain County (N.C.) (1)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (1)

- Avery County (N.C.) (0)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (0)

- Clay County (N.C.) (0)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (0)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Madison County (N.C.) (0)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (0)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (0)

- Polk County (N.C.) (0)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (0)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (14)

- Crafts (art Genres) (5)

- Interviews (43)

- Land Surveys (29)

- Letters (correspondence) (3)

- Manuscripts (documents) (16)

- Maps (documents) (9)

- Newsletters (167)

- Periodicals (48)

- Photographs (47)

- Portraits (16)

- Publications (documents) (97)

- Slides (photographs) (3)

- Sound Recordings (35)

- Specimens (38)

- Transcripts (35)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (10)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Personal Narratives (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (2)

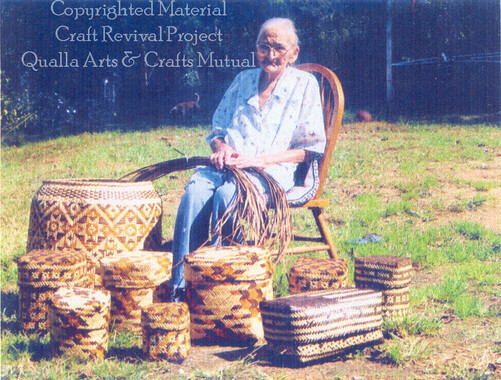

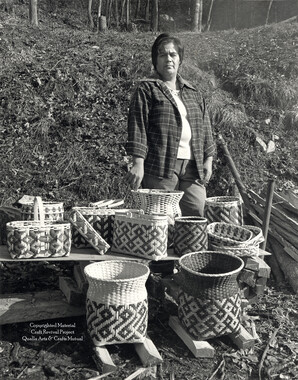

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (2)

- Sara Madison Collection (7)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (119)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (14)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (12)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (76)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (0)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- Artisans (1)

- Cherokee art (1)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (2)

- Cherokee women (1)

- Church buildings (1)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (76)

- Maps (5)

- Paper industry (1)

- School integration -- Southern States (1)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (1)

- African Americans (0)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Cherokee pottery (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Education (0)

- Floods (0)

- Folk music (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Hunting (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Mines and mineral resources (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (0)

- Slavery (0)

- Sports (0)

- Storytelling (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- World War, 1939-1945 (0)

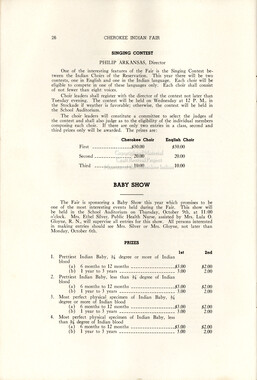

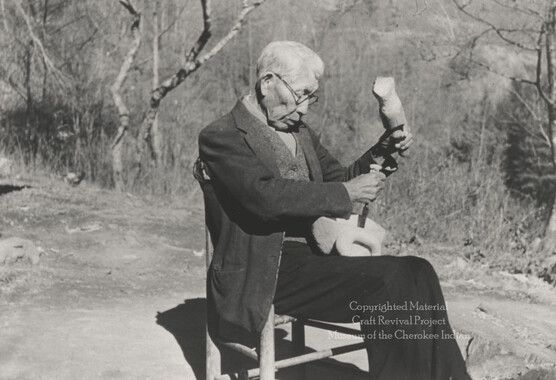

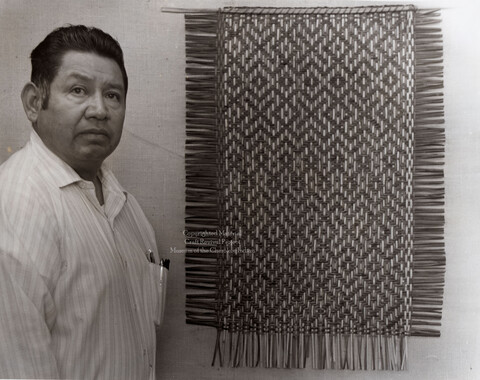

John Ed Walkingstick: Cherokee Bow Maker

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

Transcript of John Walkingstick interview June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 1 START OF JOHN WALKINGSTICK INTERVIEW Tonya Carol: Are you ready? John Walkingstick: We’re ready. TC: My name is Tonya Carol today is June 22nd, 2009 we’re here in Big Cove Cherokee, NC at John Walkingstick’s home to interview him about his bows. Sitting at picnic table with five bows sticks in front of him. Can you describe the process that you use to make the bows naming the materials and how you get them? JW: First of all you want to go out and select you a very straight tree. Once it’s brought down then you take it and let it kind of season out before you start. The first thing you want to do is you want to paint each ends of your material so it will not split. and turn it season it a little bit you can tell when the bark starts loosening up and peel all that away. Sometimes it’s very good to spray this to keep the bugs out of the material too. Then you split it up. Once it is seasoned out and split it to whatever thickness you desire and start from there. Be sure that this front side, we refer to this as the front side, The side that is a flat surface. Be sure you’re very careful with this side. When you start out you want to maintain one grain and stay with that from end to end. Because when this is going to be bending it will not separate. If you have it thisaway, showing the curved side if you bend it against the grain it will separate okay. So you want to be very clean on this side pointing to the flat side of the grain okay. All the grain can be showing on this side. The curved side It’s going to be bending it will not separate okay. Make sure it is very straight. Sometimes it’s not straight, but you have to make it straight. TC: How did you make it straight? JW: Sometimes I making it straight I just cut mine. Sometimes it may have a little turn in it, I straighten it by cutting it or using the draw, drawing, lay it out straight edge. Then I stay with that one edge right there. Measure the width of it. Try to maintain that from one end to the other. To make it then I start here, you notice I got this one marked, so from here about 20 inches in to here about 15 inches in sometimes there’s a certain length, then I start from here I will start tapering it down. See it’s tapered here. About 15 inches from end. So when it bends it’s just a little bit weaker than this is here because it’s narrow. Okay. So always start that way and then she come this way a little bit more I can adjust that too. That way I maintain, try to keep it pretty straight, straight as possible. TC: What types of wood do you use? JW: You can use hickory, white hickory, we use some of that. But here I’ve been using what we call yellow locust. And also you can use some of this what we call, if you can get a hold of it, what we call Osage orange. Which is a very good piece of material too. Transcript of John Walkingstick interview June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 2 TC: How do you get the material? JW: Okay, first you got to go out and select, go out in the woods and select. I would say the best place to locate your material is in the highest point. The highest point on the ridge or whatever you want to call it. That’s what you want to do first. Because when you locate it on top of the ridge it has a tendency to bend every which way the wind blows. It’s going to bend eastward, northward, westward and south. So this tree has been wind shaken all of those directions, okay. So that makes it very flexible in one way, you can bend it any way. Where if you cut it on one side of the hill, the wind is only bending it in one direction okay, maybe two. It all depends on which way the wind comes hits it on that side of the hill. Whether it comes from the south the west or the east, whenever it’s on top of the ridge it has a tendency to be bent in all directions. So the higher you can get your material the better off you will be. TC: Now can you tell me the process you go through to make an arrow? JW: First of all you want to also go out and select your material too. There’s two types of materials that I have here. One is river cane, very small river cane about the size of a pencil I would say, a little bigger. You want to straighten it while it’s in the green stage before you bundle it up like this, showing a bundle of about 20 pieces of river cane make sure it’s straight, then bundle it very tight so when it dries out it will remain straight. Okay it also will use what we called wild rose. Now it’s very light too whenever it’s seasoned out dried out. But it’s very strong too. Those are the two materials that they use more or less. For tailing it we use what we call turkey feathers and for tipping it, arrowheads that have been flaked out. The feather now is tied by using some of this, holding up a spool of sinew. This feather is fastened on. Well I don't have it cut here, but it’s usually tied on this way, okay. Taking two feathers and putting their tips together on the end of an arrow with the quill at the top. It seems that he would tie the tips of the feather to the arrow and bend them down so the quill is now on the bottom. Then when it’s tied down, then it’s bent down, okay, he bends both feathers down so their tips are at the top of the arrow and their quill is at the bottom bent down, then it’s tied down here. Whenever you shot it rotates a little bit. Almost like your modern arrows today. They’re all based on you kind of got a little twist so that they rotate in the air. That allows this point when it’s fastened on it travels with that rotation. Holding arrowhead at tip of arrow and motions forward movement into animal. Whatever it penetrates it will have a tendency to rotate too, so whenever you get to pull it back out it’s very hard to pull back out because most of the time with these high shoulders on it speaking of arrowhead it gets caught and you can pull it back. Best to shove it on through or cut it out. Now I don’t have one here, but there is what we refer to hunting arrowheads. Our arrowheads for hunting would have round shoulders. Pointing to the shoulders of the arrowhead. It would just have round shoulders here at the long piece. So whenever it penetrated, it went in, you could easily pull it back out both ways. So you can withdrawal it very easily so it can be used over once again. Okay. TC: What kind of material are the points made out of? Transcript of John Walkingstick interview June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 3 JW: Flint. Flint, you know we have some pretty good flint, and we have some that’s not so very good, but it can still be used. Most of our flint would have come from Kentucky, Tennessee. Now flint is not native to this area here, it was brought in, it was carried into this area. Now the only flint that may be native to this area maybe a little quartz that’s it. Other than that there’s black and white flint. Which usually have, more or less your black flint would have come from Tennessee and Kentucky. More or less your white flint is coming from further west. TC: Have these materials that you use always been used? JW: These two materials, have as far as I know have been used. I would say the yellow locust has been used probably the longest. I would say because it is native, more native to this area. Hickory could have been used a little later on. When they found out it could have been used. More of them were used, or made from yellow locust. Now most of these in this time were not made in this design that I have here. Because these did not come about until metal tools were introduced. Prior to that it was just a piece of piece of yellow locust probably small sapling. That’s why when he David Brewin said that some of these bows were very hard to pull back at one time. Because they were more round in shape at one time from a young sapling. Once it dried out they just kind of scraped it down to narrow it down so they could get that bow shape in it. Okay. That’s what made them so very strong at one time. They were more or less wrapped to make them a little stronger too. These only came about after metal was introduced. TC: About how long does the whole process take to make a bow? JW: Okay, yeah, the old way or the original way? TC: Well both. JW: Okay, the older way would have probably taken a pretty good while because they didn’t have the knife to whittle it down. It was more or less the scraping method that was used by some of the flint that was flaked off. Good piece of flint and you can flake it off and it is sharp as a knife. You can even take piece of glass and scrape very, you can scrape it. Scraping bow with an arrowhead. Flint will scrape that. There was a scraping process that was used to taper it down because they didn’t have the knife to whittle so it was a longer process. But once the metal knife was introduced you could make one bow within a day. Now that’s after it is seasoned out. There’s a long process to season it out. You get it and let it season out first before you make the bow. TC: How long do you let it season? JW: Well I’d say about six months. It’s kind of a slow process if you don’t have a dry kiln [laugh] to place it in. okay. But once you get it dried out, you get it down to where you want it with the tools we have today you can make a bow. Now that’s just one bow, not 2 or 3 of them, one bow probably within a day, well let’s just say a day and a half probably. Transcript of John Walkingstick interview June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 4 TC: What about the arrows, how long? JW: Arrows, now once you get it in to straight here all I do is cut them off to the length that I want. Now more than 32 inches. No more than 32 inches. So it’s going to be probably here. Making a holding back a bow motion. That’s all you you’re going to have when you bend that back. You’re going to pull that back to here. You don’t want to go back here, you want to stay here. With the tip of the arrow still touching the bow frame. About 32 inches. Then you’re going to cut them all off. See that’s pretty straight right now, it was straightened dried out that way. But I usually take the river cane, I usually I don’t worry about this end here The end with the arrowhead as much as I do this end the end with the feathers. This is the most important end. I will cut it off here, pointing just above a joint maybe a half inch or an inch above the joint right there so that this will not split. Then I’ll if I’m going to shoot it I will wrap it off with some of this sinew. Picks up a spool of sinew I’ll wrap it off that’ll keep it cause of the poundage on some of these bows here whenever you let go it’s going to split that. So I’ll wrap it off sometimes, have to keep in reinforced so it won’t split. But you want to make sure, you want to cut it off here above one of these joints, then make your little notch in there and it won’t split. Okay. TC: And what end would that one be for? JW: This would be for where you place the feathers. [Fletching] will be on this end. Arrowhead will be on the larger end. That maintains the balance. TC: So how long does it take you to get all that straightened out and dried out? JW: Okay, I can straighten that out within a day. This river cane that’s about 2 dozen. It’s about 2 dozen right there. I can straighten them out within a day’s time and then wrap them up and let them dry that way. Be sure that they wrapped up pretty tight. Because they’ll even get loose whenever they dry out they kind of shrink just a little bit. Same way with this, this will kind of shrink a little bit too the wild rose. These have been cut about six months, pretty close. I’d day at least 4 anyway. I keep them up there in that building where they don’t get wet, it’s very hot in there too so that helps a little bit too. You always want to cut everything a little bit longer than what you need. Even your material for your bow. It needs to be cut longer than what you need because you’re going to get a few splits on the end. So you can do away with that once it’s it won’t split over there in the barn, but if you cut it exactly what you want and it splits then sometimes when you make this you’re going to have a split in your bow. So you have to shorten up on your bow. Always cut longer than what you need. And that way you have so much to play with. TC: And how long would you say that it would take you to make a point for one of them? JW: One of these points, okay. We’re going to have flint, we’ve got flint, you can make one of these in about 15, 20 minutes. Transcript of John Walkingstick interview June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 5 TC: How did you learn how to make the bows and arrows? JW: Well I don’t… I would say… how did I learn is that what you said? Okay. Well I just learned by doing myself, wasn’t anyone taught me. I always figured I could do it. Now I seen, I seen a little bit, but not that much. But I had seen some handmade bows by some of the older gentlemen one time and I figured if he could do it I could do it, so I just practiced, practiced and practiced. When I make a bow it has to be, it has to suit me more than it does the person I’m selling it to. Because this is part of me okay, this is a reflection of me in each one of these bows. It has to satisfy me more than it does the person that I’m selling it to. I want that person to be pleased with what I make for them. Quality is very important to me. Cause it shows who I am. TC: Now, why did you want to make bows? JW: Well nobody else seemed to be making them. Everybody makes everything else. They make everything else, everything that is real easy to make. But bows is a little bit harder and nobody really seemed to want to get involved in that because… They like to work with white hickory sometimes because you don’t have to, you don’t have to you don’t have to maintain this as much tapping the bow with the white hickory as you do with this. Okay. This one right here is going might need a little bit of work on it yet but I’m not really interested in that one. Talking of a bow in front of him. I just use this kind of for demonstration. But this does have kind of a bad place right here. I may have to wrap it off about right there. Just to reinforce it here and maybe right there. So that when it bends it will not separate. Wherever this is pointing to a grain that is very curved if I bend it that way it’s going to separate here. It’ll either separate here or here or there. Pointing to various spots with a larger grain Or here or here, or probably here. If you bend it this way. Toward you with the grain side facing u. On back side see I try to maintain a certain… you don't have the grain on this side. You’re not going against the grain okay. TC: Whenever you reinforce it what material do you use? JW: I use what we call artificial sinew. That’s what I got on it here. Cause it’s got weak places in those places where I had to wrap it off. I can feel those whenever I bend it I can feel those places. TC: Do you know what that sinew is made out of? JW: Well at one time the sinew would have probably been made out of what we call Wild Indian Hemp. There’s three or four different types of hemp out there. Sometimes some people seem to think of marijuana, marijuana is one type of hemp too. But that, it wasn’t really what the Cherokee used at one time when they refer to as Indian Hemp. Indian Hemp grows in low places, along some of these bottom lands. You can tell when you get a piece of hemp weed, you can’t seem to break it you have to cut it. Transcript of John Walkingstick interview June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 6 TC: Okay. How long have you been making your bows? JW: I would say probably I would say at least 25 years. It’s something that I just learned on my own. I’ve always took pride in making a bow. Like I said it’s got to satisfy me before I can put it up for sale. I don’t like to sell something that’s going to come apart. TC: Have you taught anybody else to make bows? JW: No, no no one seems to be interested. A lot of young people would like to make a bow, but there's too much work in it. They want everything, they want you to go out there and get the material. That’s one thing I hate too, because people want to learn, they want to learn a lot of the hand crafts, but a lot of them are not willing to go out and search for the material to make it. They want it all handed to them so they can just pick up a knife and whittle one out. They don’t want to go out there and hunt the material to make the bows. That’s the same way you’ve seen baskets too. They don’t want to go out and hunt the basket material, they just want to pick up the spools and start weaving the basket. There’s a lot of work in to going out there and getting that material and getting it ready before they even start. That’s why the price is so high. That’s why the price is so high for one of my bows, there’s a lot that goes into making a bow. Everybody thinks you just pick up a piece of material and whittle you out a bow and it’s made. No it’s not. The material has to be selected. You have to go out and select your material, make sure it’s what you want. Make it as clean a piece of wood as you can get. It’s very hard to find a piece of wood that does not have what we call sap knots. May look good on the outside, but that sap knot, very small knot on the outside, but that knot goes all the way to the heart of the tree. It kind of weakens up too unless it’s pretty thick. TC: Have you noticed any changes in making the bows from when you first started making them to now, maybe how other people might make them, the length, the material, anything like that? JW: Well one thing that’s really happened as I’ve seen. The material is not as good as it once was. There’s not as much good yellow locust out there. Most all of the old locust has been stripped away from our mountainsides here. There’s not much, well you see some locust growing right there, but that’s not very good locust. The reason it’s not very good is because it’s what we refer to as [field] locust. It’s just a sprout has come off on a old stump. That’s what we refer to as [field] locust. He went in, our forefathers went in a clear-cut this land. Cleared it off. Wherever they cut down a locust tree, they didn’t dig up the stump, they left a little bit of root there and an old sprout came up off of that we refer to as [field] locust, but it’s not very good. You want to go out and find one that’s well you can almost tell by the bark on it on the tree. If it has real rough bark it’s called first growth. It’s never been off of an old stump or something. But now if it has that flakey bark like that has up there, that right there, the little old tree standing right there. If it has that flaky bark that’s [field] locust that’s not very good. The grain in it runs [real hard] even trying to split that it’s very hard to split. If it’s good locust it’s very good. But if it’s the kind that binds together and you have a hard time then it’s not very good. Transcript of John Walkingstick interview June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 7 TC: Have you ever used one of your bows to hunt with or know anybody that has? JW: Yeah, I know a couple of people that’s went on hunting trips, but I haven’t heard anything about it. I even sold the game warden a bow, he’s taken it out west to one of the Indians out there, he wanted one of my bows to use for hunting. I don’t know whether he did or not. TC: Now, you were talking about the pounds behind the bow, can you explain that a little more? JW: Okay, one of these you saw it a little while ago. That’s pretty close to 50 pound pull, right. You want a pretty strong bow, but any bow will kill. It doesn’t have to be 50 or 60 pounds, if you hit the animal just right it’s going to penetrate and it’s going to kill. Shock kills quicker than anything. The Indian never made any long shots, like you see long shots being made today. He never made no shots 100 yards or even 50 yards. All of his shots were only about 20 or 30 feet away sometimes. So when he shot these… an Indian whenever he hunted, he always waited for the game to come to him. He tried to kill the scent he bathed in some of these old herbs to kill the human scent. So when it was in the woods the animal didn’t even know he was around. He knew, went out tried to locate what the animal traveled or used a lot, so he laid in ambush for the animal to come by. So when he came by very close, the animal didn’t even know he was there. And when he shot it sometimes the animal dropped right there because shock kills quicker than anything. Now if the animal knows you are around the adrenaline in the animal will start pumping and the heart beat increases to starts pumping the blood much faster. When you shoot that animal you may have to track it a mile before you find it. Because he’s harder to kill once he’s frightened, but if he doesn’t know you’re around and you shoot him, shock will kill him quicker than anything. Okay. TC: Can you describe the first time, how you felt the first time you made your first bow? JW: Well the first bow I ever made I was very proud of it. [laugh] The first one I ever made. But every time I make a bow I want to improve on it every time I make it. So every one is a little different than the next one in quality and all of that. It’s like you know if you make a basket and your first one is not as good then your second one or your third one you’re going to make. So each time you make one you want to improve on it just a little more. So bowing is the same way. TC: Do you remember what you did with your first bow? JW: Well it’s always been very hard for me to keep a bow. Every time I get a bow someone wants it and sometimes I’m kind of a little reluctant to make a price because when I make a price most of them don’t back down they just buy it so it’s very hard for me to keep one. [laugh] I’m wanting to keep one of these, but you know if somebody comes along and offers me a pretty good price I’ll probably sell it to him. But I’ve got one at the co-op right now that I’m probably going to keep or exchange one of these for it. Transcript of John Walkingstick interview June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 8 TC: How did you feel the first time somebody offered you money for your bow? JW: Well… well I thought it was very exciting for me to be able to make a bow that somebody wanted to buy. They didn’t really want to buy it for hunting or anything like that. The first one I ever made they more for less wanted it for decoration. Now I make them for both ways. If you’re going to buy one of my bows you know you can use it for either way. I try to make it that good you can either hang it up for decoration or if you want to shoot it you can shoot it. So I’m very proud of my bows. TC: Is there a way that you can recognize your own work when you see it? JW: Yes, by the quality. There’s just, well everybody… you see my bows, if you saw [a bow] one of these touching bow, but can’t see exactly what he is touching you’d probably know it was mine. No two people make a bow or anything the same way. That’s you saw, you know baskets, you’ve seen the lady artists that make baskets, you can tell who’s made that basket without even signing it. Because of the quality that goes into it. That’s the way it is with bows. A person makes a mask, whenever he makes a mask he uses the facial features in them. That person’s reflection will be in that mask. Because that’s the face he sees all the time. He don’t see any other, he just sees that one face so whenever he carves out a face his features will be in there. You’ve seen all these masks hanging in some of these galleries and all this. You can almost tell who carved them. For instance you take the Medicine Man, you know the mask that’s hanging in there, you ever been in there? You’ve seen the facial feature in them masks you can just about tell who carved them. TC: Can you explain the importance behind knowing how to make the bows? Why do you think it’s important to keep making them? JW: Well it’s something that’s it’s a dying art. It was almost like the river cane baskets until we started teaching the classes. Now we’ve got quite a few basket makers that are making the river cane baskets. You know there was only about two people left that could do that. Most of the elderly women had past away. I think me and Stan [Two Nine] maybe Robert Queen are about the only ones that really make bows anymore. Some people make some but there’s not quality in them. TC: Well how does it make you feel that there’s only a few people left that can make them? JW: Well I feel very sad about it, because something they’re losing, losing all of this. I think there should be classes given on how to make a bow. TC: If they did want to teach a class, would you be the teacher? JW: Well, I’d like to be. Transcript of John Walkingstick interview June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 9 TC: I guess you’d have to be, huh, one of the only ones that make them. Okay well do you make any other Cherokee crafts? JW: I make a blow gun, I make the darts. TC: Can you tell me a little bit about how you do that? JW: Okay, making blow guns, first you want to go out and get river cane first, make sure you get some good river cane, always can, if you’d like me to I’ll go get one of the blow guns if you want to. TC: Alright let’s do it. JW: We’ll take a little break here. TC: You’re all about business. JW: First thing you want to do… ready? First thing you want to do is go out and select you a very good piece of river cane, make sure it joints, the further the joints are apart, the better it is. Okay. The better. Kind of let it dry out just a little bit, or you can straighten it while it’s still in the green stage. Get it straight, then lay it up and let it dry out a little bit. Then you may have to work on it a little more, don’t be in too big a hurry. Just straighten, take your time, straighten it. You straighten it by holding it over an open flame, heat it, as soon as it gets hot enough it will look like an oily [substance] will flare up on it, that means it’s hot enough, the glaze, [look like a] glaze, then it’s hot enough. Do not ream it out, knock this out until you get it straight. Why, it’s because each one of these joints holds that heat when you heat it up it gets warmer on the inside, then it will maintain your heat much longer. If you knock the end out when you heating it all your heat is escaping. But once you get it straight then you can knock it out. TC: What do you use to knock it out? JW: Well you just use a rough piece of well you can use a piece of metal. Before they had metal they would take a small piece of river cane probably take an arrowhead on it, punch it out, Taking a small piece of river cane and putting in the end of the blow gun he is working on and moving it in and out. You can punch, these are very thin pointing to the joint on the river cane. Placed a little arrowhead on the end and just punched it out. Then they just kind of twisted it too. Making twisting motion with the smaller piece of river cane. Use it like a drill bit or something wringing it out. They pull it out and have you another one piece of river cane just a little bigger, arrowhead on it. You can get it cleaned out good on the inside. Length of a blow gun I guess, regular length would probably be 7 to 8 feet long. It’s pretty hard to find a piece of river cane like that in this area right here, okay, around down on the Tuckasegee river, down the Kituwha ground. Hard to find a piece of it. It’s a little bit too high. A lot of people don’t realize, I know they got some river cane down here at the Western Carolina building down here, little log cabin. I don’t think it’s going to get much bigger than what it is because it’s just a little bit too high. Transcript of John Walkingstick interview June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 10 River cane does not grow above the 2000 foot elevation okay. Now you may get a little bit of short stuff, but what we refer to as mountain cane. Okay. Do you notice up along the flea market up along the highway, even around Cullowhee, river cane doesn’t get very big cause it’s just little bit too high. It’s just right around the 2000 foot elevation in that area. So you get any higher than that you’re not going to see any. It just won’t grow above it. It may grow up into the small stuff, doesn’t grow above the 2000. I hate to see what’s happening to a lot of our river cane right now. I seem to see a lot of it dying out. I don’t know what’s causing that, maybe the high waters or something, seems to be dying out along the riverbanks. You’ve probably noticed that too. They’re going to have to figure out to be able to save what little bit we have. Then there’s a lot of construction going on too, where they’re taking bulldozers and just bulldozing out river cane. There’s not as much as there once was. This probably came from down in Andrews there’s a piece of river cane. TC: Can you tell me about the darts that go with the blowgun? JW: Darts, the shaft is made from yellow locust. Or you can use hickory, doesn’t matter, either one works pretty good. Holding dart for blow gun. It is skinny with a sharpened point at one end. It is about 9 inches long with a tail of Scottish thistle about 6 inches long. Find you a good piece of, thicker the grain, thicker the grain on the locust the better off you are. If the grain is pretty thick you can get one of these out of it Holding up a dart. You can probably get 3 or 4 darts out of a piece there, piece about that long. Split it down real small, then you just keep splitting it down you get whatever you need. Harden the ends of it, it’s heat hardened, just hold it over the flame, don’t want to sharpen heat harden it. And its tail, is down it’s Scottish thistle. Now that grows, that might be, see that white leaves thing turned up right there. TC: By that tree? JW: Yeah. TC: mhmm. JW: That’s Scottish thistle. It’s just that big right now. It won’t start blooming until the later part of August, purple flower. Drive along the highways you’ll see all that at that time. Soon as that bloom turns white, then it will turn from pink to white to brown. Soon as it turns brown then you gather it and store it in that green stage and let it dry out. That’s what is used to tail this. TC: So how do you get the thistle on the wood part? JW: Okay, we take that, take that well you want me to get some thistle show you what it’s doing? TC: Sure. Transcript of John Walkingstick interview June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 11 JW: You want to cut it off right now. Has a long piece of wood with thistle all along it. Small clumps of thistle side by side. He chooses one clump to work with. He is carefully taking off the woody strands (the pod) to get to the downy part (the bloom) of the thistle. Once I remove that bloom… well you go out and gather it first and store it like this. Try to keep it this way on a stick all tightly together cause if you don’t it bursts comes apart, starts flying around. When you get ready to use it just remove it, remove that thing. Once he gets the woody strands off the top of the downy part he holds the downy part in his fingertips and pulls it out removing it completely from the bloom. Okay, next you want to do this. He squeezes it in between his thumb and forefinger and rubs his finger back and forth across the top of it removing the seeds. This is the seed chair okay. He scrapes out the seeds with his finger pretty hard. Once it’s done that way then I can control it. Removes wayward strands of down. I have string tied to the end of this, the shaft hold one end of the string in my mouth, start right here, as I rotate it the shaft I’ll pick it up. I’ll push it that way then I do that I’ll just rotate it. You gotta pick it up, pick that up. Picks up the downy part of the thistle by rotating the shaft between his fingertips. Okay. Understand that. Okay. Do it like I did it right there. Then you have control of it. That’s how that. TC: So about how many of those? JW: About two, two of these. And after you do that you can take one of these take a good sharp stick, we refer to this as combing it out. He is taking the sharp end of another dart and starting at the top of the thistle, he is combing through it to the bottom. After you get it all combed out, all the little [extras] you have on it, you take it He is rolling the shaft back and forth between his palms pretty quickly. End of it here. Points to the top of the thistle. Take you a piece of river cane, shove it down in there Placing sharp end first into the end of the blow gun. I would be using a blow gun like I’m using right now. Pushes the dart so that the thistle is flush with the end of the river cane. And hold that the end with the thistle over a flame and you burn it off. That one I’ll have to burn the rest of it. Okay. Puts mouth up to blow gun and blows two darts into ground. David Brewin: Could you do another one, you do one more I’ve got it wider now, just put… JW: Blows one more into the ground. TC: Well two more actually. What’s the difference, what types of animals would you hunt with the bow, and what types would you hunt with the blow gun? JW: Okay, with the blowgun, first with the blowgun, you’re only going to hunt rabbits and squirrels and maybe a little few grouse. That’s what the blow gun was primarily used for. Cause those are the easiest to kill. You can almost kill them [inaudible] they may not even see you and if you hit them they will flip over right there. With a bow, probably deer, bear, probably be used. TC: Did they ever maybe poison the tips of any of them? Transcript of John Walkingstick interview June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 12 JW: No, no poison was ever used. Cause they believed that it contaminated the meat somewhat. All the meat was used for food. TC: How long does it take you to make your darts and your blowgun? JW: Well if I got a piece of river cane I could make a blowgun probably in a day. Darts are now, it takes quite awhile just to carve out the shafts, so it takes a pretty good while. Maybe take you a half a day to a day to make maybe a dozen darts. Also you got to have this too. Lifts up the long stick of dried out thistle. Okay. TC: Now you told me that to make the bows you used yellow locust and white hickory JW: Yes. TC: And you use the same things to make that darts, why do you use those woods? JW: Because they are very strong flexible wood. Okay, they can be bent quite a bit before they break. Hickory is just a little bit better because it can be bent a little more. TC: Is there anything else you want to tell us about this? JW: No, hopefully I told you plenty. [laugh] TC: Okay. I think that’ll do it. JW: Think it’s alright. END OF JOHN WALKINGSTICK INTERVIEW John Walkingstick transcript June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 1 ` START OF WALKINGSTICK DEMONSTRATION INTERVIEW David Brewin: We’re over here at Seem to be at John Walkingstick’s workshop. John Walkingstick: This is how I put some of my river cane, straighten it and just tape it up Showing bundles of river cane with duct tape around it in three places. DB: Now do you just keep it like that to make sure it stays straight? JW: While it dries out. Because you can straighten it when it is green lay I up, seems like it will get crooked again. But if you take it and wrap like that and let it dry it will just about stay that way. Here is some of that rose. Showing a bundle of rose bundled in the same way. The bundles have about a dozen sticks in them and stand about 3 feet tall. DB: Oh wow yeah. Which one takes the most work the rose or the river cane? JW: The rose. DB: Why is that. JW: Well it’s not on the same, like you can get river cane almost the same, all of the same size, you don’t have to shape it up or, see some of this is some of this is a little larger than the other. Shoeing the rose bundle from the ends. Not all of them are the same size, but are close. DB: Yeah, let me get that. So how many bows do you work on at a time when you’re working on them? JW: Well I try to get at lest 4 or 5 or 6 how many pieces of wood I got. I get them down to see I don’t have strings on all of these, pointing to some unfinished bows standing against the wall. They are about as tall as him if not taller. I get them down to a certain point. Every phase that takes place, I do them all at the same time, that way then when I string them up, most of the time I’ll bend them before I even get them straight, or finished out make sure they bend. DB: Now when you get the bent out how do you do that to hold it, do you just string it up. John Walkingstick transcript June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 2 JW: Yeah I sting it up so it’s…what I’m more or less doing… taking string and it is tied around the bow, he pulls with effort to get it to the top, then pushes the bottom string down with his foot. . DB: Boy they’re strong. JW: I may string it up three or four times to get it all DB: That’s a heck of a bow there now. Holding up bow that he just put string on. It has a handle notched out in the center and curves downward on either side and then back up to where the string meets the ends (shallow W shape). JW: What I’m more interested in is making sure they’re all bending the same. I may string it three or four times before I finish it out. DB: Is that one about done now? JW: Yeah, this one. Pretty strong too. Pulls string out slightly from bow. DB: I could tell that. Where do you mostly sell these? JW: I sell them, I hate to say it but you know you have the biggest problem with the gift shops they don’t want to pay you what you have in it. They more or less want you to give it to them. But there’s a lot of work that goes into this. You have to go out. You just don’t take the first tree you see. DB: Yeah, I love that story when you told me about having to go up on the ridge, getting it where it blows. JW: Right. If I get any here, I’ll go very high, to the highest point, along the ridge here, take my locust from that part there because it’s been shaken all different directions. DB: Do you think… people probably don’t even think about the fact that you have to go out back in the woods to find the right. JW: No, they don’t they don’t take that under consideration. Like I said you don’t take the first tree you see. You want a more mature tree than the young one. DB: How big a tree do you cut? JW: At least afoot in diameter. You want one at least that and then you want to take it, you may do pretty good out of that foot diameter you get around six bows. That’s what you’d like too, but sometimes you’re not going to do it. John Walkingstick transcript June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 3 DB: So the next thing after you got that log back down is you’d have to split it out is that what you do? JW: Right, whenever I split it out. I got a piece right here. This is not a very good piece, but I’m going to just show it to you. Holding a piece of wood taller than himself. DB: Yeah. JW: See I cut them and then I cut them down to almost DB: That is a lot of work. JW: Right. You get it sometimes you got to take sometimes you got to work with it, you may have cracks out here, splits out here a little bit. Pointing to the outer edge of large piece of wood. Sometimes you may have split out here and you got to take it down until you get rid of the splint, the split in the wood. DB: Right how about these knots, can you work with knots. JW: You don’t want the knots. That’s why I said that this is not a very good piece of wood, it’s just an extra piece I had over. DB: But it does show the size of the piece of wood you have to work with. JW: Right. And you want to take this off right here. You may take an inch thickness off of this, but you want to pick you out one of these grains. See the grain 6:55 both looking at grain. DB: Yeah, so that’s what you want to work to is to that grain. JW: The best thing for you to do is to get you something that you can see that grain real well and mark that one grain, just stay with that one grain, mark it all the way up over the end of it here pointing to top of wood. See now that has crack in it too sometimes, split in it. looking at top. DB: Oh yeah. JW: You can see the grain here. Come up this way and then you got to pick that one out. Following one skinny piece of grain up to the top and over the top. Stay with that with one grain over here and back down. Just mark it off. So that’s going to be your outline. That split you got to split in the piece of wood though and it don’t disappear you may have to go a little deeper. DB: Now you taught yourself how to do this pretty much though didn’t you? JW: Right. John Walkingstick transcript June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 4 DB: That’s JW: You want you want to stay with one grain. Picking up bow, See now I stayed with one grain, see what it looks like on the back side of this one, see what it looks like on the back side. Showing the grain on the bow going straight up the bow. DB: That’s really nice. JW: See now you can see the grain in this one. See how it stays with the grain, see it come up and DB: Yeah, that’s a good piece. That’s neat. JW: That’s why I have that grip right there because everything changed in the middle. The same way grain is still the same in this one. Shows how at the notched out handle the grain is the same line all the way. You don’t want this you don’t want this the grain showing on this side. The front side. DB: Why would that be? JW: Okay, if I bend it back this way it’s going to separate here. Okay, see if you bend this back right there. Take this motioning bending the bow in the opposite direction than it should so he is showing that if you bend the bow with the grain on the outer curve it will separate and break. and bend it back on that it’s going to separate, that’s why you stay with this one grain on this side because everything is going to be bent against that. DB: How did you figure all this out? JW: [laugh] Well it took some time. DB: But you really, there was no other older Cherokees around here that you go to and say how did you make bows? JW: No, I… I had seen I had seen a couple bows made, I didn’t see the person sitting there making it, but I had seen quite a few homemade bows. Everybody’s bow is different, there’s not two bows that are alike. It’s like an artist. Take someone who paints a picture, another artist can come along and his picture is not going to be exactly like the previous one you know. Whatever he learns it’s all his. Sometimes we look at when you paint a picture of a face, if you ever become an artist and you paint a picture of faces, all these faces in all of your figures will resemble your face, why because that’s the face you always see. DB: Yeah, that’s true. We interviewed somebody else that talked about that they used to have when he was a boy, he’s about your age I guess, they’d have these archery contests like on Saturdays or Sundays do you remember anything like that? John Walkingstick transcript June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 5 JW: Well probably by the time I come along they were just having them at the Indian fair, they had archery there about every day. DB: Okay JW: At the Indian fair. These older Indians, these old Indian chiefs, most of them standing along the streets. They also had targets you know sets up too. They get up there on the street and have a place fixed out between two buildings, like the buildings running toward the river. Have an old target set up down there and they’d stand there at the edge of the street demonstrating you know. DB: When I was a boy I did it when we came to Cherokee. JW: That’s what you saw probably. DB: Street chiefs out there that had their blow guns and the bow and arrow out there. JW: Yeah, demonstrating. DB: I got a picture of me, I can’t remember his first name he was a Lambert he was the longest running chief. JW: Henry Lambert. DB: Henry Lambert. I had my picture done with him. And just before he died, I took my youngest daughter over and got a picture of her. JW: Me and him are about the same age. But he well he wasn’t a chief all his life, he used to be police chief an all that. But when he got too old about the time to retire, he couldn’t satisfy everybody so he quit or retired [inaudible] then he started chiefing. He did pretty well. DB: Look like you could make pretty good money doing that tactually. JW: Get used to it, you got to work the system. DB: I’d rather do it like you do. You don’t get the tips, but. JW: That’s the reason you stay with that one grain. Cause you want that, see you don’t have none of that on this side. DB: Now the Osage orange, is it the same consideration JW: Same consideration. Any wood you get, I don’t care what kind of wood you gunna get. If you’re going to bend it you don’t want to bend away from this. I guess that would John Walkingstick transcript June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 6 be what you would probably say, away from this the grain side if you bend it back toward me it would be away from that the grain. It’s going to separate. DB: Okay, let me get another close up of that. JW: It will separate right there. If you bend this back toward me. DB: That makes sense now. JW: It’s going to separate. DB: Otherwise it’s compressing and pushing together. JW: Right, so when you bend this way it doesn't do that. That’s why you kind of leave a couple of solid pieces all the way through. DB: How about making arrows, what is the process of making an arrow? JW: First you got to go out and get you some mountain river cane, mountain cane I guess you would call it. Sometimes have you ever studied about any of this? Holding bundle of mountain cane in his hand. DB: No, JW: Sometimes, I know I’ve heard some people… to my experience you know like all the river cane up where you live in Cullowhee, I consider that mountain cane. DB: Like up on Caney fork up in there. JW: Right that’s all mountain cane to me. You know you get even river cane big enough to make a blow gun, you’re gunna have to go down around Murphy or Andrews or down in around Toccoa, Georgia to get river cane big enough to make a blow gun. DB: Is that because it’s a little warmer down there so it has a better growing season? JW: I guess it is. Now river cane doesn’t grow above the 2000 foot elevation. DB: Okay, never knew that above 2000 right? JW: Right you notice out here at Gateway, river cane growing there. And then you come this way, you don’t see none. You go all the way up here through here in Big Cove you’re not going to see noee, too high, you’re about 2,500 feet right here in this area here. Now they got a little bit growing down there by this little Western Carolina building in front of the children’s home, youth center. And that cane is not going get much bigger than that because it’s too high. They may think it’s going to get [laugh] a little bigger, but it is just too high for it. John Walkingstick transcript June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 7 DB: I was interested, tell me about how you harvest the cane, as opposed to other people the way they do it. JW: I go out and locate. I didn’t get this, by anyway, when I go out and gather it, I want to gather something that doesn’t have these, doesn’t have these sprouts on it. You want to get something that doesn’t have sprouts on it. DB: It’s cause it has that little groove in there right. JW: This too whenever… you’d like to get one that is smooth all the way, you can find it in there. This probably come from the outside of the cane break. All of that you see, along the road from here to Sylva, you’re going to see branches on it all the away up. Now you got to go inside of that. DB: So when you get in the middle where the cane is? JW: Right right. See how I got bamboo sprouting up here. Pointing camera to bamboo stand. DB: Yeah. JW: Okay, so if anything comes up it’s going to start branching out, you see a couple of them right over there branching out in the other side of this tree over there. DB: Yeah. JW: Sprouting out because of sunlight. Now you take some if you take one on the inside of. Now you tell them that’s bamboo in there, don’t tell them that’s river cane. DB: Oh no, we know that’s bamboo. But you really can’t use bamboo, you couldn’t make a blow gun out of bamboo could you? JW: Some people say they got, some people will say we got river cane at my place, I believe that’s what it is they’ll say. I’ll say are you sure you do? They say, well I think so, how will I tell the difference. See that bamboo, okay the branches, how are the branches on there tell me what you see which way the branches are going straight out. Looking at a stand of bamboo, the branches are coming straight out from stalk of plant. DB: Yeah that’s right yeah JW: River cane, you take out river cane those branches. DB: River cane goes right up more up the stalk and bamboo goes out like that. John Walkingstick transcript June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 8 JW: Right branches near the tree. See how them branches are on it, just go straight out, that’s what makes it so bushy. DB: Yeah, JW: That river cane will stay just as close to that. I think it’s due to the root span. See this river cane has just a very small root span. Do you ever notice it will be rounded off here on the bottom. DB: I’ll have to check that the next time I look at some. JW: Okay, pull one up or dig one up. You’re going to have roots goes right around the bottom, they won’t be much further than that. That’s the reason the branches don’t go much further they stay very close. DB: That would make it fall over yeah. JW: These roots have the long root span, see, like that tree right there see that walnut tree right there, this little tree right here, the root span is as far as those limbs extend. DB: So wherever you see the limbs that’s where the roots would be. JW: Right as far as they extend out there. That’s the root span that far. DB: Now you told me something the other day that’s really interesting when you cut it off it’s [saved] for somebody, can you explain that. JW: Okay when you’re cutting the river can always go in and… do you want me to do one for you so you can see how it’s done. DB: If you don’t care. JW: You got it off. Break in tape JW: While we looking around see how this see how that little piece of bamboo is right there see that little one right there, if you was going to make an arrow shaft that’s what you want. Showing small piece of bamboo So you cut this old bamboo. DB: Let me get back behind you. JW: You want to be sure you cut below the surface. Chopping at bamboo near the ground with an ax. Cause if you don’t where I cut that off there will be a bunch of sticks sticking up right there. See that right there. And you don’t want that. When you cut that John Walkingstick transcript June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 9 off you want to leave a bunch of sticks, but if you cut if off below the ground you won’t have that. DB: Right. JW: I can’t even tell where you cut it actually. Pointing camera to the ground. DB: Right. JW: See how them limbs, bamboo. If this had been river cane all these branches would be running right up real close. Bend in the branches. DB: You told me something interesting the other day before I forget it I want to make sure that I did ask you that today. You told me Cherokees have no word for good bye. JW: No. DB: Why not? JW: Cause all of us felt like if we didn’t see you tomorrow or the next day that we were going to see you in the life hereafter. So they believed in the life hereafter. That’s the reason good bye never entered the vocabulary. That’s the reason no Indian across the United States ever had a word for good bye. Cause they all felt like if they didn’t see you tomorrow or the next day they going to see you in the life hereafter. DB: So what did you tell somebody in Cherokee? JW: You would say [Cherokee words] that means I’ll see you later, I’ll see you in the morning. DB: I like that. Do you speak Cherokee fluently? JW: No, I wish I did. My father spoke fluent Cherokee. DB: I guess when you came along people were trying to say you shouldn’t learn it. JW: Okay, but anyway, see my dad went to school when there was boarding schools here and they were forbidden to speak the Cherokee language at that time. In the early early 1920’s in that area there. They were forbidden to speak the Cherokee language. So rather than have me go through that and suffer what they had suffered, because if they spoke it they were severely punished. So rather than have me go through that they taught me English. So I would have to go through what they went through. DB: I looked in the village the other day those little 5 and 6 year old kids speaking Cherokee. John Walkingstick transcript June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 10 JW: Yeah. Yeah, they can speak very fluent in the Cherokee language, but we have the immersion classes teaching them. That’s the best place to go where the children just learning to speak. DB: That’s the way you would have learned as a child. JW: Right that’s where you learn everything. Your first six years of life is the most important time in your life, that’s your learning period. Once you get 6 you’re already set in your ways, pretty hard to change that. [laugh] DB: Of course, you and I are still learning. JW: I learn every day, there’s not a day doesn’t go by that I don’t learn something. It’s a new experience every day. Sometimes just to get up. DB: This brings back, when did you start making bows? JW: I guess I would say, in the late round about the 70’s I guess. DB: Haven’t really been doing it…. JW: But I always made little ol’ bows out of little ol’ sticks or something tied the string on it. After I saw big bows to be handmade I said I believe I’ll try to do this. DB: How about the flint knapping, did you teach yourself that too? JW: No, I learnt this from some elderly gentleman in the Indian Village. Probably seen a postcard with a person on it that was flinting. Flinting that’s me. DB: Oh really. JW: Early 50’s, I mean late 50’s ’58, ’59. DB: That’s neat. JW: Did that there in learned… remember ol’ Haze Laucy DB: I knew Haze well. JW: You knew him? I learned to make darts from him. DB: I knew Haze is a real character. JW: Blow guns and darts I learned from Haze. Haze is a character all right. DB: You know how he learned to speak English don’t you? John Walkingstick transcript June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 11 JW: No I don’t. DB: In the penitentiary. JW: Yeah, he spent time there. DB: I gave Tonya a recording I did of him years ago he talked about you know people there aren’t real men around I think anymore. He talked about he’d leave here and walk to Cosby, Tennessee, get there at breakfast make liquor all day and sometimes he’d walks back home. JW: Okay, right here at the head of Big Cove, but what we call Three Forks, back in [inaudible] Three Forks, back at Tri Corner Knob, drop off about 20 miles, it’ll be Cosby. The only problem they had was after they got the liquor they’d start back up and once they got to Tri Corner Knob, an old cabin right there, a shack, they stopped right there and most of them got drunk, some of them froze to death right there. DB: Wow. JW: Too drunk they couldn’t build a fire. DB: He had some great stories. JW: He spent a lot of time in Cosby too, Haze did, spent a lot of time in Tennessee running off liquor. DB: That’s how he put food on the table for his family for a pretty good while it sounds like. Then he got caught and I think he spent three years in Atlanta, and that's where he really learned to speak English he said. JW: Other than that he’s a good old person DB: He’s a wonderful man. JW: Yeah, he was. DB: I have fond memories. JW: He’s help you in any way he could teach you something. DB: Yeah, he really would. Yeah he was trying to teach me Cherokee but he’d say the words… JW: Then laugh at you John Walkingstick transcript June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 12 DB: Yeah, and it would leave me about as soon, he’d go around and point out what a dogwood was. I wish he was still around, I’d love to get some video of him. JW: He’s a good old person. I liked old Haze. Me and him was real close when I worked with him. DB: Oh really was that at the Village where you were working with him? JW: Yes. I DB: I bet he was hoot. He used to come to Mountain Heritage Day like you did. He’d sit out there and they had a pathway down there and he’d be shooting his blow gun, right in front of people. People would be walking by and all of a sudden a blow gun dart go right by their knees out there. JW: Remember Sim Jessan, DB: No I don’t that’s not a familiar name to me. JW: He used to be in Woodcarving, he carved a lot of those masks. DB: The only woodcarver I knew until Davy was G.B. Chiltosky. JW: Yeah. DB: Medicine man. JW: Right. DB: Probably not many of them left anymore is there. JW: No, well there’s a few of them try, but they just don’t go at it the right way. None of them has let’s say, none of them has the power [laugh] as they once had at one time. DB: I guess that had to be a special gift. JW: Well at one time everything was translated through the Cherokee language and that’s what makes it so hard for a lot of our people today because most of them don’t speak fluent Cherokee language. So some things can not be translated into English, they can only be translated through the Cherokee language. When you translate it to English then it looses all it’s you might refer to it as flavor, looses all that meaning whatever. So that’s the reason a lot of us want to get back to speaking the Cherokee language cause we’re missing out on a lot of things that we don’t understand. DB: That’s your culture is all tied up in your language. John Walkingstick transcript June 26, 2009 Mountain Heritage Center 13 JW: Right. Right. DB: Yeah, I’m seeing that more and more, just how that language is, it’s so descriptive the language. English is not. JW: Right DB: English like my wife and I were talking English is a language of commerce, if it’s something to do business with. JW: That’s all it is good for. DB: Cherokee’s are not capitalist. JW: No. END OF WALKINGSTICK DEMONSTRATION INTERVIEW

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

In this video interview, Cherokee artist John Ed Walkingstick demonstrates how he makes the most of what he has in life and takes only what he needs for his carving. His careful selection of materials for ceremonial pipes and bow making are rooted in Cherokee tradition. The transcript provided is an unedited version of the video.

-