Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (19)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- Allanstand Cottage Industries (62)

- Appalachian National Park Association (53)

- Bennett, Kelly, 1890-1974 (1295)

- Berry, Walter (76)

- Brasstown Carvers (40)

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943 (26)

- Cathey, Joseph, 1803-1874 (1)

- Champion Fibre Company (233)

- Champion Paper and Fibre Company (297)

- Cherokee Indian Fair Association (16)

- Cherokee Language Program (22)

- Crowe, Amanda (40)

- Edmonston, Thomas Benton, 1842-1907 (7)

- Ensley, A. L. (Abraham Lincoln), 1865-1948 (275)

- Fromer, Irving Rhodes, 1913-1994 (70)

- George Butz (BFS 1907) (46)

- Goodrich, Frances Louisa (120)

- Grant, George Alexander, 1891-1964 (96)

- Heard, Marian Gladys (60)

- Kephart, Calvin, 1883-1969 (15)

- Kephart, Horace, 1862-1931 (313)

- Kephart, Laura, 1862-1954 (39)

- Laney, Gideon Thomas, 1889-1976 (439)

- Masa, George, 1881-1933 (61)

- McElhinney, William Julian, 1896-1953 (44)

- Niggli, Josephina, 1910-1983 (10)

- North Carolina Park Commission (105)

- Osborne, Kezia Stradley (9)

- Owens, Samuel Robert, 1918-1995 (11)

- Penland Weavers and Potters (36)

- Roberts, Vivienne (15)

- Roth, Albert, 1890-1974 (142)

- Schenck, Carl Alwin, 1868-1955 (1)

- Sherrill's Photography Studio (2565)

- Southern Highland Handicraft Guild (127)

- Southern Highlanders, Inc. (71)

- Stalcup, Jesse Bryson (46)

- Stearns, I. K. (213)

- Thompson, James Edward, 1880-1976 (226)

- United States. Indian Arts and Crafts Board (130)

- USFS (683)

- Vance, Zebulon Baird, 1830-1894 (1)

- Weaver, Zebulon, 1872-1948 (58)

- Western Carolina College (230)

- Western Carolina Teachers College (282)

- Western Carolina University (1794)

- Western Carolina University. Mountain Heritage Center (18)

- Whitman, Walt, 1819-1892 (10)

- Wilburn, Hiram Coleman, 1880-1967 (73)

- Williams, Isadora (3)

- Cain, Doreyl Ammons (0)

- Crittenden, Lorraine (0)

- Rhodes, Judy (0)

- Smith, Edward Clark (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (2393)

- Asheville (N.C.) (1886)

- Avery County (N.C.) (26)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (161)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (1664)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (283)

- Clay County (N.C.) (555)

- Graham County (N.C.) (233)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (478)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (3522)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (70)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (4692)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (25)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (12)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (10)

- Macon County (N.C.) (420)

- Madison County (N.C.) (211)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (39)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (132)

- Polk County (N.C.) (35)

- Qualla Boundary (981)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (76)

- Swain County (N.C.) (2020)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (247)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (12)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (68)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (72)

- Aerial Photographs (3)

- Aerial Views (60)

- Albums (books) (4)

- Articles (1)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (228)

- Biography (general Genre) (2)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (38)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (191)

- Crafts (art Genres) (622)

- Depictions (visual Works) (21)

- Design Drawings (1)

- Drawings (visual Works) (184)

- Envelopes (73)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (1)

- Fiction (general Genre) (4)

- Financial Records (12)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (67)

- Glass Plate Negatives (381)

- Guidebooks (2)

- Internegatives (10)

- Interviews (811)

- Land Surveys (102)

- Letters (correspondence) (1013)

- Manuscripts (documents) (619)

- Maps (documents) (159)

- Memorandums (25)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (59)

- Negatives (photographs) (5735)

- Newsletters (1285)

- Newspapers (2)

- Occupation Currency (1)

- Paintings (visual Works) (1)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (1)

- Periodicals (193)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (12982)

- Plans (maps) (1)

- Poetry (5)

- Portraits (1657)

- Postcards (329)

- Programs (documents) (151)

- Publications (documents) (2237)

- Questionnaires (65)

- Scrapbooks (282)

- Sheet Music (1)

- Slides (photographs) (402)

- Sound Recordings (796)

- Specimens (92)

- Speeches (documents) (15)

- Tintypes (photographs) (8)

- Transcripts (322)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (23)

- Vitreographs (129)

- Text Messages (0)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (275)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (7)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (336)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (2)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (20)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (7)

- Blumer Collection (5)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (20)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (2110)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (282)

- Cataloochee History Project (65)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (4)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (5)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (1)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (112)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (1)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (4)

- Frank Fry Collection (95)

- George Masa Collection (173)

- Gideon Laney Collection (452)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (2)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (28)

- Historic Photographs Collection (236)

- Horace Kephart Collection (861)

- Humbard Collection (33)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (1)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (4)

- Isadora Williams Collection (4)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (47)

- Jim Thompson Collection (224)

- John B. Battle Collection (7)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (80)

- John Parris Collection (6)

- Judaculla Rock project (2)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (1314)

- Love Family Papers (11)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (3)

- Map Collection (12)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (34)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (4)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (44)

- Pauline Hood Collection (7)

- Pre-Guild Collection (2)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (12)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (681)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (1)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (94)

- Sara Madison Collection (144)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (2558)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (616)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (374)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (510)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (16)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (32)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (1744)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (2)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (109)

- African Americans (388)

- Appalachian Trail (35)

- Artisans (521)

- Cherokee art (84)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (10)

- Cherokee language (21)

- Cherokee pottery (101)

- Cherokee women (208)

- Church buildings (166)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (110)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (1830)

- Dams (95)

- Dance (1023)

- Education (222)

- Floods (60)

- Folk music (1015)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (2)

- Forest conservation (220)

- Forests and forestry (917)

- Gender nonconformity (4)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (154)

- Hunting (38)

- Landscape photography (10)

- Logging (103)

- Maps (84)

- Mines and mineral resources (8)

- North Carolina -- Maps (18)

- Paper industry (38)

- Postcards (255)

- Pottery (135)

- Railroad trains (69)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (3)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (452)

- Storytelling (245)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (66)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (280)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (328)

- World War, 1939-1945 (173)

Interview with Morris and Wilma Simpson

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

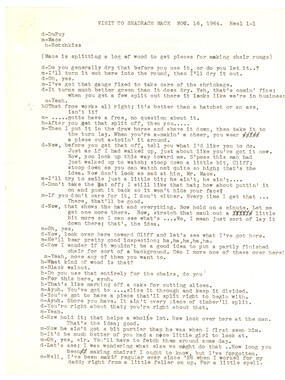

1 Simpson and Simpson WESTERN NORTH CAROLINA TOMORROW BLACK HISTORY PROJECT Interviewee: Morris Simpson (S) and Wilma Simpson (WS) Interviewer: Lorraine Crittenden (I) County: Jackson County Date: May 19, 1986 Length: 56:25 Background information: Morris Simpson born in Asheville, NC - April 8, 1914 to Lake Simpson and Marie Pollard Simpson. Siblings: Katherine Simpson Pea, Annie Lee s. Holmes, Mattie Marie Casey. Deceased, Irene S. Simpkins Louise B. Morris, Thomas Lloyd Simpson, William E. Simpson – deceased. Morris is a Veteran: #22, 271st Air Force Base Unit PFC - 2 years, 10 months, 14 days Lorraine Crittenden: Mr. Simpson, has your family always lived in North Carolina? Morris Simpson: My immediate family has. I: Did your fore parents? S: No, my grandmother, she lived in, she was from Ettowa, Tennessee. I: How did she get to North Carolina? S: She came up from Blue Ridge, Georgia, to work in Bryson City. I: Where did she work in Bryson City? S: She worked for Dr. Bryson, Judge Bryson. I: Would you trace your family history back as far as you can, beginning with your father’s side of the family? S: My grandmother… I: What was her name? S: Mattie Simpson. I: Mattie Simpson. S: Mattie Simpson. I: Was she born and raised in this area? S: McMinn County, Tennessee, Etowah it was. I: Do you remember? Would that be your father on your father’s side? S: Do I remember? No, I’ve never seen him. 2 Simpson and Simpson I: Do you remember his name? S: Yes, his name was Will Coleman. I: So, your grandfather was Will Coleman? Now, where was he born and raised? S: I don’t know. I: Did you ever know him? S: Didn’t, I never did. I: What about your mother’s parents? S: I knew my grandmother and my great-grandmother, I’d seen her. I: What was her name? S: Malinda Pollard. I: Pollard? Now, that’s an uncommon name for this area. Where did she come from? S: Virginia I: Now, was she a slave? S: I don’t know. I: Oh, you only saw her once? S: Once, yeah. I: You didn’t hear your grandmother say? S: No. I: What was your grandmother’s name? S: Katherine Pollard. I: Where was she from? S: She was Katherine Brown Pollard. She was from Jackson County. I: Do you know where she was born in Jackson County? S: No, unless it’s what they call Hog Rock up here. I: Right, I’ve heard that name. S: Yeah. I: Did she always live in Hog Rock? S: No, she left here years ago. I: Where did she go? S: Asheville. 3 Simpson and Simpson I: Asheville. S: Yes, and stayed there for years. I: Okay, I believe you told me her name. S: Katherine Pollard. I: Okay, she went to Asheville. S: Katherine Brown Pollard. I: All right. S: She ran a café over there. I: So that was her main source of income? The café? S: At that time. I: Where was that located? S: It was down around the depot in Asheville. My grandfather, his name was James Pollard, he was a school what is now called Johnson C. Smith. It was another name for it back before that. I: So your grandfather had a college education? S: He went to Johnson C. Smith. What I mean before, the name is changed now, but it was another name, the school. It was the Presbyterian school. My mother went to Presbyterian school in Asheville when she went to school. She didn’t go to the public school. She went to Presbyterian. I: Now, was this high school? S: Huh? I: Was this high school? S: Where she went? I: Right. S: I don’t know how far it went. I don’t, but the Presbyterian school is a private school. I: So, your grandpa was a school teacher and your grandmother ran the café? S: Right. I: Did you hear the older family members say that they were well off? S: No. I: Did they own their own home? S: Well, I doubt it. No, they didn’t own their own home. They didn’t own their home. I: What else do you remember about your grandparents? 4 Simpson and Simpson S: Well, that’s about all other than my grandmother. Just that she was around, you know. She and my aunt. She lived with my aunt, and my other aunt, Annie Bell Pollard. I: And they lived in Asheville? S: Asheville, yes. I: What about your mother and father? S: My mother and father, well, they married at an early age. My daddy was a railroad breakman for the Southern Railway. We never wanted for anything. We got along, you know. We had something to eat like everybody else. Well, during the Depression he was cut off, and of course he worked for the WPA. I: Now, what’s WPA? S: What is that? I: Work Project Administration? S: Work project, it is something like that, yes. I: Was this in Asheville? S: No, this was in Bryson City. I: So, your parents met and married in Asheville? S: Yes, we were all born in Asheville, but Louise. I: So, how many brothers and sisters did you have? S: Eight. I: Eight? S: In all. Seven of us was born in Asheville. I: So, you lived there for several years? S: Yes, I was about thirteen or fourteen years old. I: When you moved to Bryson City? S: Yes, it was during the Depression. I: So, did your father move because he thought that he could get work in Bryson City when he couldn’t in Asheville? S: Probably so, could make it easier there because he was cut off, you know, off the railroad. You know what I mean. There wasn’t nothing running, no transportation, moving the freights or anything. So, no jobs. I: Well, what did he do in Bryson City to earn a living? S: Well, as I say. He worked for the WPA and around and about. Odd jobs until they called him back to the railroad. You know, to go back to work. 5 Simpson and Simpson I: So, what was your mother doing at this time? S: My mother, she worked some, not much. She worked some, you know. I: Did she stay home most of the time? S: Most of the time, yes. I: But during the Depression she did some domestic work? S: Yeah, domestic work. Yes. I: How much education did your parents have? S: Well, I think my dad got to the fourth grade, and I’m sure my mother, she finished grammar school. I: So, both of your parents could read and write? S: Right. I: They attended school in Asheville? S: No, my dad went to school and he got, I guess was in Bryson City. Presbyterian school in Asheville. I: Mr. Simpson would you clarify how your father, Lake Simpson, came to Bryson City? S: He came to Bryson City with some of my grandmother’s friends, brought him up to Bryson City when he was a young man, about ten or eleven years old. I: Now, where was he before he came to Bryson City? S: He was in Ettowah, Tennessee. I: When did your grandfather, your father, Lake, move to Asheville? S: When he got a job with the Southern Railway. He was about fifteen. I: Fifteen? S: Yes, he was a train porter. He was a porter there until about 1916 and he went to breaking. Him and a friend decided that there was more money in the railroad, breaking than it was porting. I: Now did he get to come home each night, or did he? S: Sometimes. He’s running from Asheville to Charlotte or some place. It would take him about two days. About the third day he’d be back. I: Into Bryson? Asheville. S: But when he was on a local, we lived near Bryson city, he’d be home at night, every night. I: So, he did this all his life? S: All his life. 6 Simpson and Simpson I: Wasn’t that considered a pretty good job? S: Good job. Good as you could get at the time. I: Now did your mother and father own their home in Bryson? S: Yes, they did. They owned their home in Bryson. I: Did they also garden for their produce or? S: Some, yes, we had a small garden around the house there. There was eight of us and it took quite a bit of food. [laugh] I: Garden couldn’t have been too small. Did you and your brothers and sisters get a chance for an education? S: No, we didn’t. My sister, Louise, she was the only one that finished high school. I: Where did she go? S: She went to Allen home. I: In Asheville? S: Asheville. Katherine, she went to the ninth or tenth grade. She’s also now working on her GED. I: Is she? S: Just about to finish it. I: OH, that’s wonderful, how old is she? S: She’s sixty something. I: You’re never too old to learn. S: So, that’s it. Well, we went by the white schools to get to a black school. I: Where is this now? S: From Bryson City to Sylva. I: After you finished? S: No, the students after they finished, I said at that time you had to pay to go to school if you went or got to Asheville and get somebody to stay with, you know, and all and go back to school. After you finished the seventh grade in Bryson City, that was it. I: Were many people able to afford to go off to school? S: Some, not very many. Not very many. There’s more that didn’t than that did. I: Did any of your family members get to go off to school? 7 Simpson and Simpson S: Yes, two of them. My oldest sister and my younger sister. I: When your family moved from Bryson to Asheville? S: No, from Asheville to Bryson. I: Oh, I’m getting confused here. Did you move to Bryson after the breakman job? S: Yes. I: He was still working as a breakman? S: Yes. I: Asheville was his home? S: No, Bryson City at that time. I: Did he manage to buy that home in Bryson? S: Yes. I: after he got back to the railroad. S: Yes, after the Depression. Well, I guess it was still a depression, but he did manage to get it started, you know, and then finished it later. I: Well, how did he manage during the Depression with eight children and no job? S: Well, he had a grandmother. I mean a mother that helped him. I: Oh, and she lived in Bryson? S: Yes, mother helped him. I: Do you remember the Depression? S: Yes, I do. I: What do you remember about it was. S: It was very depressing, [laugh] a lot of beans. I: A lot of beans? S: Yes, eating. I: What kind of beans? S: Pinto beans. I: Pinto beans, they are still around today. S: [laugh] That’s why I don’t like them now. I: You had more than your share? S: Yes, well, that’s about all that I know I guess. 8 Simpson and Simpson I: Of the Depression? S: Yes, I know it was rough. I know I went to work once in Daddy’s place. He was getting a check from disability there. Getting two checks. I told my dad to let me go on the WPA and I went and worked a week. Looking at a pair of shoes that I was going to buy and I got a check. It was five dollars. I: You had worked all week. S: I had worked fifty hours. I: Fifty hours? That’s about ten cents an hour? Did you buy the shoes? S: I asked the lady to get the shoes. She said, “What do you want?” Because I knew, you know, and so I said I’ll take mine to dry goods. So, she said you can’t have all of it in dry goods. You’ve got to have half of it. I like to blowed up. I: Why was that? S: Well, you got to take part of it in staple, you know, groceries. I: The money from the WPA? S: Yeah, half of it staples, and half on dry goods. [laugh] I liked to blowed up. I: For fifty hours work and you still didn’t get those shoes? S: Daddy gave me the money. I: Now, you said your father was disabled? S: He had rheumatism and arthritis. I: During the Depression? S: During the time. Yeah, for a while you know. I: So, at that time there was Social Services? S: No, he had insurance, disability, you know, sick insurance. So, he had two checks coming in, so he wasn’t hurting too bad. I remember one time they said they were going to cut my daddy’s check off. Daddy says, “If I can get down here to a lawyer Randolph’s, they’ll start taking my money, not giving me my money.” They started them too. Pretty good chunk. Prudential, I remember. I: Prudential? S: Yes. I: What other historical events do you remember? S: Well, now I can’t think. Well, World War II. I: World War II? 9 Simpson and Simpson S: Yes, I didn’t go into action. I was stationed in Kearney, Nebraska, at the time during the war. I was lucky to stay there, could volunteer to go, but it was segregated, you know how that was. I: No, could you explain that? S: Yes, all blacks at one place and all that over another place. Everybody wasn’t together. No, not in the Army. Just like you in this house and I’m in that house, white and black. I: Did you fight together? S: Oh, they finally got them fighting together. The units, different units, but I wasn’t in the action. You know what I mean. I didn’t go over. I: But you heard about it? S: Yes, I knew about it. They’d attach you to different squadrons, you know. I: If I remember correctly, there were white troops and black troops… S: Right. I: During World War II. S: If you remember like I believe the 92nd a lot of times and the 24th infantry, they’d attach you to another organization, you see. The blacks really didn’t have. The white man, he was already gone to National Guard and he was over you when you got there. Done made lieutenant you see. But the black didn’t have the chance to go at that time. Segregation. I: Those who were in the Army, were they given a chance for promotions, equal pay? S: Well, I don’t know about the pay, but the rating, I imagine, it was, but they sent you to school, yes. They’d send you to school. I: For what? S: Signal Corps, the radio, you know, and different things like that. I: What did you go for? S: I didn’t go to school. I: Okay. S: No, I didn’t go to school. I stayed at one place the whole time that I was there. I was in what you call, I was in the Air Force, but attached to the Air Force, but it was more or less like a quarter master, hauling stuff and trucks and sometimes you did guard duty. So, that’s about all I guess that I know of about that. I: World War II? S: Yes. I: What do you remember about the social conditions of the black family? S: Well, it wasn’t always good because you’d have to go to the back if you wanted to eat. We didn’t get hungry, you know [laugh]. We couldn’t go no place, you know, without you had to 10 Simpson and Simpson take you lunch with you on the road. You’d have to go in the back. Dan Israel is the onliest man in Bryson City that opened up for the blacks. He did fix a room in there decent for the blacks, he did that. He’s about the only one that I know that did that. When they built the theatre, they fixed a balcony for us. I: A theatre in Bryson City? S: Martin, I asked him one day was he gonna puta balcony in the theatre over there and he said no. So, now we all go to the same place [laugh]. Wilma Simpson: Even when Mr. Frye built the Fryemont Theater there in Bryson City over by the First Citizens Bank building, he built a balcony in it. And we could always go to the show for ten cents. I: What about the circuses? Could you attend the circus? Were you segregated then? S: Yes. I: In a different place? S: White man over here and black… WS: See, the circus was… S: All the bus drivers would be there on the bus Saturday to tell you to get to the back. WS: But the whites that wanted to sit in the coaches with us if they could. Oh yeah, there were white people that like to sit in the back coach and all, where we were or something like that, but we couldn’t go back in the coach where they were. S: But on the bus seating, you know, you want to sit back there you know all people are not alike. Some good and some bad, but you can always tell when a guy is right and when he’s not. WS: But one thing about Bryson City, we did always play together. I: I was gonna ask. What about children playing? S: Yes, they played together, we played ball together. As far as along that line, well, it was the old heads that was pumping the kids. Such so is now, you know. You can always tell when a kid’s been raised to treat people right. Always, but you know some peoples got the old die hard in them, and they don’t want to give up. I: Do you remember then when a lot of people were farming that if a neighbor was sick, black or white, that the community no matter what, would pitch in? WS: Oh yeah, they did that. S: I was telling somebody in Bryson City, an old lady, Sherrill. They used to have cottage prayer meeting. Her and my mother and then would go and them would go from house to house. There wasn’t nothing between them, you know, but that’s the way it was. WS: Then if somebody died they would call the white neighbors would come around. The blacks would go into the homes when they lost loved ones and all. We always had that type of relationship. 11 Simpson and Simpson S: Of course, the relationship you know, here in the western part is not like it is in the eastern part. You know, down where those plantations is down east. I: Right S: Different. I: Western, North Carolina. S: Yes. WS: Let me tell you this. I think we had better relationships in Bryson City. Really, when things really got some of the whites were so steamed up because of the black children coming to school and things like that and all. But back in our days and all, well you knew your place and they’d come and play with us and we’d play with them. Well, the neighbors they’d visit each other and all from Bryson’s Branch. All of them, they’d visit back and forth and all like that. And come in and lend a hand and you know, and all like that and everything. But the real problems did come with segregation, see, because some of them want to see blood flow. I: Integration. WS: Yeah, integration. Some of them so bitter against that, but as far as other relationships in Bryson City now, we had real good relationships. I: As long as you kept your place? WS: Kept your place and we all knew where our place was and we all abided by it and all like that. We didn’t try to go in places. S: As far as the white man, he wants to be our superior and that won’t work. I never could think it would work. WS: They were always Mr. and Mrs. to us and all that. Our fore parents was Aunt and Uncle to them instead of Mr. and Mrs. Howell. They were kin to us. S: Claimed kin to you instead of calling you Mr. and Mrs. I: Would you think of just a moment about the black church. Why do you think it was so important to the black community? S: The black church, we depended on the church because we know the Lord would see us through and that’s why we stuck to the church. It was Christian people back in that day. They meant what they, when they went to church they meant, they knowed they were living the life. And they know that he could see them through. I: Can you think of another reason the black church was important other than being assured that the Lord would see them through? WS: It was your very own where they couldn’t come in and ruin it. Absolutely, it was our own church and they could not boss it. They come when they wanted to. The whites visited our church. Well, they took one whole side. Granddaddy Howell was one of those strict ones. “That’s the white people’s side of the church.” They wasn’t always the poor class of whites, but the bigger class that did come to our church and all. The summer people would come there to our 12 Simpson and Simpson church and I seen one whole side of our church just full of whites. But as I said, when we went to their church we went on invitation only. They come to ours when they wanted to. When we went to theirs, believe you me, we was invited to come. And I didn’t go. Very little. Very little, but during World War II, I’ll guarantee you they wanted us there. I: Why is that? WS: Have them praying for the war to end and all that. They had their times of prayer that they’d invite us to come in for world day of prayer and things like that and all. I: Is that when the World Day Prayer started? WS: I thought so, but I gathered in some of my material that it had been going on years, but in Bryson City when it become really prominent during World War II. I don’t know what they did in World War I but in World War II they banded together and, you know, praying and all. And of course, when the war was over I guess when you went to the selected board. I: Were when you were treated raw, when you went, when they called you or whatever? S: No, I went selective board, yeah, when I was selected. Some of them would say, “Why ain’t you in the service?” I’d say, “Well, I’m going when they send for me.” It was just like lottery you know, like it is now. I: When they call your number? WS: Yeah, when they call your number Morris’s number fell out in Bryson City, it scared him to death. S: It didn’t scare me. [laugh] I was in Virginia [laugh] I: What were you doing in Virginia? S: I was working in Virginia. I: Were you married at that time? S: No, I wasn’t married then. I: You married during the war? S: Yes, I wasn’t married then. I was working for the Virginia Engineers. Your Uncle Rueben was up there with me Julius and all of us and Doc. I: What were you doing in Virginia? S: We worked for the Virginia Engineers Construction. I: Was this one of your first jobs? S: First good job, fifty cents an hour. [laugh] Seventy-five cents on Sunday. I: Oh, so you worked seven days a week? S: No, double time on Sunday and seventy-five on Saturday. 13 Simpson and Simpson I: How old were you? S: Oh, I don’t know. Twenties, maybe. I: Mr. Simpson what did you do after you finished school? What did you do to earn a living? S: Well, I went hoteling. I: Where… S: Waiter. I worked at the Brookside and I worked at Cherokee. I: Brookside Grill in Bryson City. S: Here and there, yeah. I: And then in Cherokee. S: Awhile, yeah, in Cherokee. I: Where in Cherokee? S: Up at Newfound Lodge. Then I worked one and half a season up to the Fryemont Inn, half a season, house cleaning. I: Where was this? S: Bryson City. Anything to pick up a nickel, a dime, to keep from stealing [laugh]. We made it though. I: When did you settle down in one place? S: One place? Oh, after I got out of the service. I came up to the Enloes and worked for them and then I left there and went to Western. I: What did you do at the Enloes? S: I was a chauffeur, butler what you might say. Then I went up to the housekeeping at Western Carolina and retired there twenty-two years and a few months. I: Did you and your wife work for the Enloes together? WS: Yes, we worked there together. I was the cook and the maid or whatever and he was the chauffeur, butler or whatever. We came up there in 1948. I: As a couple? WS: As a couple and lived there in the house. You know I told you up there where we lived and all like that. I: Well, tell me some of the things you did as his butler, chauffeur, companion. S: Oh, we would go to Florida and then we would go to Spruce Pine quite a bit. I: What was in Spruce Pine? 14 Simpson and Simpson S: The Harris Clay Company where they made some expensive clay came from there. They made expensive china. We’d go down to Bryson City up on Toot Holler. They’d always get some clay up there. That’s where some of it came from and during my time with it. Of course, they’ve been in business a long time before I went to work for him. We’d go down to the beach, down to Nags Head. I: You all went? Oh, you went with them? WS: Yes, two weeks down to the beach. I: Now, what did Mr. Enloe have to do with the clay? S: Clay Company. Well, he was President of the company, Harris Clay Company, the time that I worked for him C. J. Harris, this hospital is named for, he was the owner. Mr. Enloe worked for him. He also managed it. He was the President of the company after Harris died, for about 12 years. The main office was in Dillsboro. WS: The mines and things were in Spruce Pine. S: They had an office over there. WS: They’d go to Spruce Pine occasionally, him and Morris to check things out. S: This expensive china, I forget the name of it. The clay that they sold was made out of it. Real, high, expensive china. I: Where did you stay when you went on the trips with him? S: Well, when we would, most of the time, when we’d go there I’d get some place. Go like down to the beach, we had a beach house down there for the help. I’d stay with somebody on the road you know. Some blacks. We stayed at a black hotel in Raleigh one time and I liked to burn up. He was lying in an air-conditioned Holiday Inn. I: [laugh] Where did some of your other travels take you? S: Well, that’s about all I went with him We’d go to Asheville, Salisbury. Just all around. WS: Nearby trips except when they go to the beach and then Morris went to Florida with them one time. I: Did you have regular hours that you were on duty? S: No, we just go and finish up and when I took him some place, you know and get him settled down, and he was, see, he was up in 80. I: When you were working for him? S: Yes. He was 84 when he died. Morris nursed him the last two years before he died. Morris just stayed down at the house, at the hospital, or wherever he was. Sometimes around the clock. So, it was a good experience. I've been from Murphy to Manteo, plum across the state, so it was a good experience in doing that. WS: In your late years, he drive Mr. Hennessee down here some. 15 Simpson and Simpson S: Oh, yes, I drive W.C. Hennessee in my spare time. I: Of, the Hennessee Lumber Co.? S: Right. Formerly of the Hennessee Lumber Company. I've been to Florida twice this year. I: Is this expense free? S: Yes, expense free. I: Oh my, I like that job. WS: Expense free and paid too. S: I took Wilma down. We flew down. WS: Jack brought him back, see his son flies. Jack brought him back. This year Jack flew me and Morris down and we drove the car back. S: See, this is the Hammermill up here. Hammermill Lumber Company now. Mr. Hennessee sold it to the Hammermill. He retired. We haven’t been any place now but you know we just go when he wants me, on call. I: So, after Mr. Enloe became ill what did you do? S: Oh, I stayed with him and helped nurse him and then he passed. Then I went to the college. I: What did you do there? S: I was a housekeeper. WS: They changed our title, what were we then? Housekeeping assistants. That’s what our last title was. S: So, that’s about it. I: As far as your work experience? S: [tape pause] Yes, there’s discrimination at Western. Well, when the bulletin come out you wouldn’t get it until somebody be on the job. WS: Different job and all that. Promote the white man. S: He done got the job and the bulletin come late. Then at the time then they went to putting it out you know. WS: Used to be they’d hire, replace and all before you even knew they were going to. S: Sure, they would. I: Even before you knew there was a vacancy? WS: Before there was a vacancy, absolutely. S: If that ain’t discrimination I don’t know what. 16 Simpson and Simpson WS: In other words, the black man was the underdog always, absolutely, he was always the underdog. S: Cliffton had to go down there and cry for a job before he got that and raised sand about it. [tape stops] WS: He didn’t know the hall from the corridor or whatever [laugh] lights being out and everything and have to ask some of the others what it was. He probably had a little schooling… S: He was looking up there and said, “let’s turn on the light up here Simpson.” So I said, “Well,” I looked up there and it says corridor on it. He looked up and says, “I don’t see.” So I just flipped it, I said, “there it is” and flipped it back off, the light. He says, “Where was it?” [laugh] He was dumber than I was. I: So, he didn’t know hall wasn’t a corridor. WS: The main supervisor. If he was going to be off, would let them be the runner while he was off and get them moved up. Then they used to say you had to finish high school. S: Well, we had high school graduates and they didn’t put them up there, anyway. WS: Didn’t have any black ones up there as janitors. Harvey called himself going to high school and couldn’t spell “fork!” I told you when I helped him to take inventory he wanted to sit with the pencil and paper and I had to spell everything I told him to put down. [laugh] We are glad that we stayed on until retirement. But it was hard, see back in our days us women had to scrub and all that, everything. Well, we still do it now. They still doing it now, not on a big scale. They send janitors in to help last few years that I was there. See, they finally separated. The men did all the heavy work. S: Equal pay equal work, that’s what they were doing. WS: When I first went up there in 1960, Mr. Presley was our janitor and all he did was we gathered up trash and he brought it down and put it on the elevator and all. He did all the mopping and everything. We did the bathrooms and things like that. We did all the cleaning. Then he came along with the scrubber or mop or whatever. But then after it got on the same equal basis then we had to run them scrub machines and all just like the men did. They finally separated us. See, they took the janitors out of the girl’s buildings and all and took the maids out of the boy’s buildings. We were just women housekeepers and men housekeepers. I: Were things easier then? WS: No, see that’s when we really had to do our own scrubbing and everything then. Shucks no, it wasn’t no easier because that’s when we had to start riding them scrubbers up and down them halls and them mops and things. Then that went on until the last few years I was there in the summer time. They did finally get to letting the men come in and help us to a certain extent. We'd go to their buildings and help them with the ladies part of cleaning, dusting and all that we'd do for them. We'd wax with a mop out of the bucket and that wasn't hard. They'd do the scrubbing and all that mopping the dirty water up. We'd come along down the hall and put the wax on. So it got easier as far as that hard work, doing venetian blinds and things that we did do. Some of them might still do it now though. The last year I was there students got to working with us that would help you to keep from being as hard as it had been. 17 Simpson and Simpson I: Mr. Simpson over the years have you noticed that life or survival for the black family has become easier? S: Yes, in a lot of ways it has. You have better opportunity if you're qualified. You get the jobs. I do admit that. But, the way it is with a lot of people they are just – some of them are just. I don't know the word for that. I: Receptive? S: Well, a lot of them are receptive in every way, but it’s just the people that’s backward, you know, that treat you ignorant, I’ll say. Well, it is. It’s people that don’t want to accept you and don’t want these things to be like they are. That’s the way it is. You take people that’s… WS: Some would always like to keep you down as far as that’s concerned, but then there’s others that are willing. S: Now, you take the Ku Klux Klan. Here they go, they want to be your superior! The black man’s superior! It’s not so much for the white but he wants to be the black man’s superior. It always has been. That’s not gonna work ever. WS: Some of us housekeepers could take courses or something like that if you were eligible to take a course. We could’ve took our time on it, an hour, or whatever or your lunch hour. Now, one of the white ladies that was with us, Betty [Litro] she took her dinner hour and finished up her secretarial courses. Of course, she’s a secretary in one of the offices up there now. I don’t know exactly where. So, some of us if they wanted to if they qualified and all they could’ve took some of the courses that would’ve advanced them or something like that and all. Now they did allow that. To certain extent things are getting better all the time. To a certain extent. S: They’re not a hundred percent. WS: At least they got black supervisors now and all that. I don’t believe when Clifton died I believe a white man has his job, but see [inaudible] still has hers. [tape pauses] I: What are some of the religious customs that you remember that we don’t have now that you had then? S: Well, you used to go to church in the morning and have morning service. You’d go home and come back and have the evening service and then you go home and come back that night. Now, they just have one service. Sunday school and service. Most of the times in our church. And a lot of others. You don’t have it. You used to go to the river and baptize. Now, they say it’s polluted. You have to have a baptistery. Men would put on a pair of pants and maybe a light top shirt and they’d be baptized in that. That was amongst us blacks. Women would have on a robe, kind of 18 Simpson and Simpson heavy robe, white, and dresses with robe around it. Be baptized in the creek or the river and now you have the baptistery and a lot of things has just changed now. WS: We furnished robes for our ladies to be baptized in our baptistery, terry cloth robes. S: So, it’s a lot different. Back then they didn’t use to have as much money to do things, you know, as they do now. You might say that, take the Bryson city church, the beautiful pews that they have there. A lot of churches couldn’t buy those pews back in the olden days, you might say, but everything is getting modern now and people got more money, handle more money now than they did then. People tithe and that helps the church. If every church would tithe, then churches would do better. I: But in the earlier days people didn’t tithe. S: They didn’t have much to tithe with. I: How were the ministers paid? S: Well, they just take what they could get. No certain salary just take up a collection. I: So, the minister’s home wasn’t provided as it is today? S: No, and a lot of churches don’t have homes for the minister, parsonages. Now we couldn’t in our church, we couldn’t furnish a parsonage because most of the people down there that’s carrying the church on is retired. The biggest portion of them. But now the pastors, young man, now you’ve got to have him a parsonage, telephone, pay his social security and everything. That’s really expensive, that’s why you don’t see many domestic workers now in homes because it would take a bundle to pay you to work a week. Where in people used to work for three dollars a week, five dollars, six dollars. I know my grandmother got about 6 dollars. WS: Our last years down at Enloes we got thirty dollars a week. And, of course, room/board, house and all that and everything, all expenses. I: But you could make it? WS: Oh yes, bought our cars and everything. Your first car was thirty dollars and sixty-five for his first real good one. You could easily make, you know, your car payments and all then on your salary and you know a housekeeper. S: It wasn’t a hundred dollars. I: A car wasn’t a hundred dollars a month? S: No, Claude Queen showed me down there one day. He had a Chevrolet and I think he paid about seven hundred dollars for an old Chevrolet back then. He showed me the bill of sales on it, seven hundred dollars. WS: He paid about thirty a month on that Chevrolet that we had. Yeah, thirty dollars a month and then you paid about sixty-five on the next one I think, sixty or sixty-five. It didn’t get over a hundred dollars a month on a car until, I mean a car payment, until we brought that Jet Star in 1965. You paid little better than a hundred dollars a month on it new. That’s just the way things run back in them days. 19 Simpson and Simpson S: Things are out of sight now, what I mean is high. Plus you make more money. I: Can you think of anything else about the church or the church services that is different? WS: Choirs are robed up. I’ll tell you one thing that I was telling somebody one day. I don’t know whether they ever experienced it or not but when I was young and growing up down in Bryson City, see communion was just passed around, you sip and that one sip, and all like that. I: One of the same cup? WS: Yes, but now a days you’ve got your little communion set. Everybody’s got their individual glass but really they passed it around. I was telling them something the other day. I said the first time they passed it to me, I got strangled. I was twelve years old when they passed that communion around and I got strangled on it. I was so embarrassed [laugh] See, cause it was pure wine. We use grape juice but they had wine back when I was a kid. The communion was wine. I: Oh, so I imagine everybody… WS: Pass it around and you take a sip. It might’ve been two or three glasses of it, but you drank after each other. As you say, customs. That was just a way of life for us. We didn’t expect it no other way and all. S: Most of our ministers now have been to seminary because I know about my brother when he started out preaching. If he hadn’t went to seminary, he wouldn’t have been the preacher, you know, as good as he was. But other preachers, you know, they would call old timey. They just had to study. So, lots difference now, these days, modern days, and I like progress, personally myself. But a lot of people don’t, that’s why we don’t have a lot of factories out this way because people wouldn’t sell them the land, you know, them that had land. You take down there in that Bryson bottom down there. Look at it now. Dr. Bryson would never sell it. WS: The tannery would have been down there if he would have sold it. S: They say Dayco would have been down there but they wouldn’t sell the land, wouldn’t leave the land. But look at it now, if it ain’t cut up now, courthouse and all that. WS: We’ve come a long way, let’s put it that way. I: What were some of the most memorable occasions at Western for you? WS: Well, back when we were still working at Moore’s in the gifted children, we had this little black girl that was in that group of gifted children. They were staying at Moore’s, and of course that was still in the segregated days and all. She was assigned to a room by herself. We had maybe a couple of rooms or so forth at Moore’s that had their own bathrooms and all. And they put her in that bathroom. She didn’t get to sit in the lobby or anywhere with them. We had some seats in the hall. She was just, well, the gifted student which was young students and all. She’d sit out there by herself because she was the lone black, the only one that was around. And I tell you, Linda Towns I forgot what Linda’s last name was, she married Bill Towns lives over here in Webster. She was with that group. She was staying at Moores and all at that time. Cause she hadn’t come here and married and lived here and all. Well the next thing, when the college was really integrated and all, now that was the high school gifted students. Grammar school or high school, whichever they were. Then we moved to Helder in 1966. Our first black girl to stay down there in the dormitory was Doris Doggett, Nancy Burns and we had one more, there was three of 20 Simpson and Simpson them. I can’t think of that other one’s name. The rules was there was two beds to a room which meant one of them had a room all by herself. They did share the same bathroom. They lived on the south wing of Helder which points over towards Leatherwood and all. That was our first three black girl students that stayed in a dormitory down there. Then Henry Logan. Henry Logan come and they did a little more integrating when Henry Logan come down. Henry Logan was here when we were up a Moore’s Doris and them come after we went down to Helder in ‘66. S: Nancy Burns was from Tryon, her father was Methodist preacher and she stayed with us because she couldn’t get a room up there and they had to wait. WS: She had to be on the waiting list because of some illness in the family. No, she was sick herself and she didn’t get to come at the beginning of school and she had to wait until the drop out, so she come down to the house and stayed with us until Elvie could take her. Then she stayed with Elvie until she could get back in the dormitory because I didn’t keep her full-time. She’d been too lonesome down in Dillsboro. So, Elvie took her in the after she got arrangements made. And she stayed with Elvie and all. Rode back and forth with Elvie and Melvin and all them like that until she could get back in the dormitory. And then of course as I said when we had, getting back to Leslie now… well anyway when Leslie… [end of tape]

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Morris and Wilma Simpson are interviewed by Lorraine Crittenden on May 19, 1986 as part of the Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project. Born in 1914, Mr. Simpson discusses his family members and growing up in Bryson City, North Carolina during the Great Depression. He recalls segregation of troops during his time in the Airforce in World War II. Mr. Simpson and his wife Wilma describe segregation and integration in Bryson City. They both remember church services. Mr. Simpson recalls his work as a butler and chauffer to the Enloe family at Western Carolina University in 1948. Wilma also describes working as a housekeeper at Western, the job discrimination she witnessed against African Americans, and seeing some of the first African American women living in the dormitories during the 1960s.

-