Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2683)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (7)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6592)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- 1700s (1)

- 1860s (1)

- 1890s (1)

- 1900s (2)

- 1920s (2)

- 1930s (5)

- 1940s (12)

- 1950s (19)

- 1960s (35)

- 1970s (31)

- 1980s (16)

- 1990s (10)

- 2000s (20)

- 2010s (24)

- 2020s (4)

- 1600s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 1910s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (15)

- Asheville (N.C.) (11)

- Avery County (N.C.) (1)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (55)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (17)

- Clay County (N.C.) (2)

- Graham County (N.C.) (15)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (40)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (5)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (131)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (1)

- Macon County (N.C.) (17)

- Madison County (N.C.) (4)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (1)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (5)

- Polk County (N.C.) (3)

- Qualla Boundary (6)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (1)

- Swain County (N.C.) (30)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (1)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (3)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Interviews (314)

- Manuscripts (documents) (3)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (4)

- Sound Recordings (308)

- Transcripts (216)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newsletters (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Publications (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- African Americans (97)

- Artisans (5)

- Cherokee pottery (1)

- Cherokee women (1)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (4)

- Education (3)

- Floods (13)

- Folk music (3)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Hunting (1)

- Mines and mineral resources (2)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (2)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (2)

- Storytelling (3)

- World War, 1939-1945 (3)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Sound (308)

- StillImage (4)

- Text (219)

- MovingImage (0)

Interview with Frank Moody and Randall Murff

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

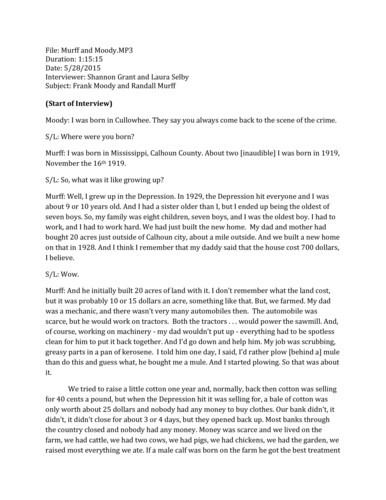

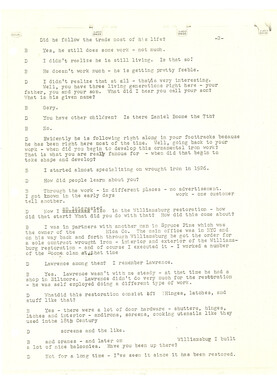

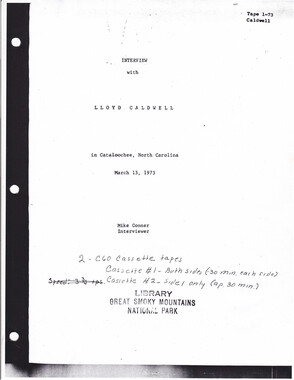

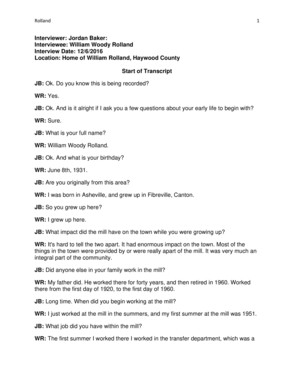

File: Murff and Moody.MP3 Duration: 1:15:15 Date: 5/28/2015 Interviewer: Shannon Grant and Laura Selby Subject: Frank Moody and Randall Murff (Start of Interview) Moody: I was born in Cullowhee. They say you always come back to the scene of the crime. S/L: Where were you born? Murff: I was born in Mississippi, Calhoun County. About two [inaudible] I was born in 1919, November the 16th 1919. S/L: So, what was it like growing up? Murff: Well, I grew up in the Depression. In 1929, the Depression hit everyone and I was about 9 or 10 years old. And I had a sister older than I, but I ended up being the oldest of seven boys. So, my family was eight children, seven boys, and I was the oldest boy. I had to work, and I had to work hard. We had just built the new home. My dad and mother had bought 20 acres just outside of Calhoun city, about a mile outside. And we built a new home on that in 1928. And I think I remember that my daddy said that the house cost 700 dollars, I believe. S/L: Wow. Murff: And he initially built 20 acres of land with it. I don’t remember what the land cost, but it was probably 10 or 15 dollars an acre, something like that. But, we farmed. My dad was a mechanic, and there wasn’t very many automobiles then. The automobile was scarce, but he would work on tractors. Both the tractors . . . would power the sawmill. And, of course, working on machinery - my dad wouldn’t put up - everything had to be spotless clean for him to put it back together. And I’d go down and help him. My job was scrubbing, greasy parts in a pan of kerosene. I told him one day, I said, I’d rather plow [behind a] mule than do this and guess what, he bought me a mule. And I started plowing. So that was about it. We tried to raise a little cotton one year and, normally, back then cotton was selling for 40 cents a pound, but when the Depression hit it was selling for, a bale of cotton was only worth about 25 dollars and nobody had any money to buy clothes. Our bank didn’t, it didn’t, it didn’t close for about 3 or 4 days, but they opened back up. Most banks through the country closed and nobody had any money. Money was scarce and we lived on the farm, we had cattle, we had two cows, we had pigs, we had chickens, we had the garden, we raised most everything we ate. If a male calf was born on the farm he got the best treatment in the world for about six, seven months. Then we’d eat [him]. And we had plenty to eat, that wasn’t the problem, we had plenty to eat. The only thing, my parents did not drink coffee, we didn’t have black coffee. The only thing we had to buy was baking powder, sulfur, salt, and flour. Everything else we had. So, we had plenty of chickens, we had eggs and we ate chickens and we, at a time, we had a few turkeys. But, we always had plenty of milk and butter and we lived on the farm. And, when I did get a chance to work - working your field and it would pay 50 cents a day. At one time I was about 16 years old and I got me a job working in the saw mill and they were cutting oak cross ties and these ties were being shipped to South America for something, down there, but it was the railroad. That was a high paying job, I make 17 and a half cents an hour. When the saw was right and we worked 10 hours a day and I made a dollar and 55 cents a day. And that was a big job. 16 years old I weighed a hundred and thirty-five pounds and I was much, much man. And so that’s about my growing up. S/L: Okay. What did you do for fun growing up after all this work? Murff: Fun? I played football in school. I didn’t play basketball. And we shot marbles, shot marbles for keeps. S/L: I’ll ask you some questions. When were you born? Moody: When? May the 10th 1918. That was a long time ago. S/L: Wow. Moody: I can remember when he was born, I was only a year old. [laughter] S/L: Who were your parents? Moody: Jerry Moody and my mama was Lyn [inaudible] Moody. S/L: What were their occupations? Moody: Well we was on a barn in East Laporte My granddaddy had three boys; he gave them all a big farm. He sent the boys to college and my father went to Raleigh. He got a degree in electrical engineering. He come back up here and they had just built the power dam in Dillsboro at that time. He got a real good job. So he was having to drive from East Laporte to Dillsboro, about 30 miles to work and take care of the farm too. And of course that didn’t last too long, because he bought a house and moved down closer to Sylva and those fields. Of course daddy didn’t like that; he’d run off and have to tend to the farm. But anyway, he had this good job with the power company and I started school at Webster when I was six years old and I stayed at Webster through the 11th grade. I failed a half year of geometry in the 11th, the last year, so I couldn’t graduate or wear the gown or that stuff. I couldn’t go back to school for a year to make up that thing, so I joined the army and, like you said, that was the year of the Depression, there wasn’t no jobs. And that army was 21 dollars a month, so I went down to Fort Bragg and stayed three years. Come back down and I was helping my daddy with the electrical business then. I got in the reserve - actually Fort Bragg - in three years and I stayed in the Army Reserve until the war broke out. But all that time between then I was working on the Fontana Dam. I worked for the TVA to fix Fontana and I worked on this dam over here in Glennville when they built that place and that give me a good start. And then I met the love of my life down there when I come home that year and she liked the uniform so well she married me, but she had to get me to get the uniform. So that gave me a good start with that dam and I stayed in the dam until it was done. And then I got on the Fontana Dam and the army called me back to come back in World War Two. So, I made it into World War Two, but in the meantime I had done a lot of protection work. I was working at Fort Bragg in the army. One thing I think gave me the good job with Eisenhower. I showed a movie for President Roosevelt in Fort Bragg and everybody there was so nervous, they said, “nothing can happen” and I said “Well, I’ll do my best.” I said “if the film breaks or the fire goes off, I can’t help that.” But anyways, the movie went off real good and I think that must have been the MOS number when I went in to the army. And I went to basic training and everything and got over to the relocation depot in England, and they called one man out, “pack your bags you’re going somewhere.” I packed the bag. They used us throughout the whole country. They picked out men that they lost, replaced them, and I got on this little English train and rode to a place called Ascot and got off with my bag. Then a lieutenant come by and said “you want to go out the base roads?” [I] showed him my orders, and I said, “I don’t know.” He looked at it and said “I don’t know what it is.” And it was SHAEF [Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force], the main headquarters of the expeditionary force, but nobody knew it then. That was real secret, Eisenhower’s headquarters. So I went out with him at SHAEF and stayed there for a little over a week. He finally found out where SHAEF was, right there in London, in the tent cities. So, he took me out there and I stayed with SHAEF all the way through World War II and I worked right in Eisenhower’s headquarters in a special service section. And when Eisenhower started coming back here politicking for president, then he shook hands with all of us and said I know [inaudible]. [He] said if I can ever do anything for you if I get in the presidency, come see me. I thought about that a lot. Of course, when I got discharged, I had my job back in Dayco in Waynesville. So, I didn’t go and at that time I had a wife and a baby girl and after [I]come back then I started working for myself at Dayco. And, let’s see, what did I do then? Well anyway, I lacked that one half of a year finished in high school and so we went to Virginia Beach and my daughter knew that I’d done work for Eisenhower. She called [the] American Legion up there and [inaudible] the uniform. They were going to decorate me. They got a lieutenant general from the Pentagon to come see me and he introduced me to Moody and I didn’t know what was going on at the time, but that was real nice. And he gave me an honorary high school diploma from Virginia and the Board of Education. S/L: Yeah? Moody: I still got it on the computer now, it’s real nice. And course since then I had a little boy, a little girl and since then I’ve lost my wife and my boy and my girl and now I’m living with my granddaughter down in Florida. I come up here and stayed in my old home up here a good three months out of the year, but I like it so well I just about stay up here now. And I really like it here. They’re really good to me here. And it feeds well and I give myself something to do every day. But, I’m a bachelor, they brought my cat up here from Florida. She’s 15 years old, so she and I get along really good together. And that’s just about the winds of it. S/L: So I was wondering a little bit about how did you hear the U.S. got into the war? Murff: I did what now? S/L: How did you hear that the U.S. got into the war? Murff: I was standing in the chow line in Camp Shelby, Mississippi waiting . . . to eat Sunday lunch. I went into the army, I went in - well back then the draft was on and every time a young man reached 21, the age of 21, he had to register for the draft and I had registered and I wanted to get to be a cadet and I made application for it and I was sent to Alabama, Tuscaloosa, to take the examination. I flunked, because I had a scarred eardrum. I didn’t know I had any problems at all. I thought I was in good shape. But I was rejected from getting into cadet training, pilot training, then. And so, I came back home and I was in the draft and I had to spend 12 months serving in the army; 12 months, and then I’d get out. So I went to Camp Shelby on December the 4th, 1941 and I left home that morning and I expected to be in the draft for 12 months and come home. Well, 3 days later, on December 7th, 1941, that’s when I heard . . . I was at Camp Shelby, waiting to get a uniform and some clothes. I was still wearing the suit that I wore down there. But anyways, I heard about the war that Sunday morning when they were talking about Pearl Harbor. I didn’t even know where Pearl Harbor was, or anything about it. So, there I was and I went to orientation there and of course new in the army they provided a number of programs for us, and I did not want to be a foot soldier in the infantry, I didn’t want that. And they gave me a choice, if I would go to airplane mechanic school, that they would put me in the regular army, raise my pay from 21 dollars a month to 30 dollars a month and I would be in the regular army serving and they would send me to school for 6 months and that was airplane mechanic school. So, I took that deal. I went to Camp Shelby. [Then] I left Camp Shelby and went to Wichita Falls, Texas for airplane mechanic school. I went into school in - on the last week of my course . . . In the meantime the army was scuffling for pilots, bombardiers, navigators, and what have you. Everybody would be a pilot and they came out with a program that they would recruit pilots with the rank of staff sergeant and so I made the application to that and got accepted. And so I went into pilot training and back then you had to - they didn’t waste any time. They were really pushing hard on everything and for pilot training they would give you 8 hours instruction and you had to solo out satisfactory for your instructor to pass. Well, I went through the 8 hours and, in the meantime, they had shipped 40 cadets from the army up in New York - cadets, regular army cadets - shipped them down there to go to school through the summer. So that really put the pressure on us. We were just regular pilot training. And so I went through the pilot training, but I didn’t solo out in 8 hours and so they kicked me out. So then I went to Garvey school and from there I went to bombardier navigator school and then from there I went to Tampa, Florida, MacDill Field and . . . was made a member of squadron. They had 4 squadrons and a company and we were put in training and I was the bombardier navigator on a B-26 and so I trained on that, for that. And we were really being pushed hard. We would go to school in the morning for 8 hours, no for 4 hours. Then, we would fly for 4 hours. Then, the next night we would fly for 4 hours in the morning, afternoon we’d go to school 4 hours. Then at night we would take a 4 hours flight at night, usually to Jacksonville, Florida, down to Miami or different places. But every other night we had to fly 4 hours. So that was pretty. In the meantime, I had managed to get a pass to go home for Christmas and my wife out talked me then. I went home I didn’t . . . I wanted to get married, but I did not want to marry. I knew I was headed for overseas and I didn’t care to have a new wife and go overseas. My wife outtalked me, so we got married while I was [on] a 10 day pass and I went back to Florida. A buddy of mine, he and his wife had married shortly before that, he was in Dallas, Texas. So we got up looking for a room, somewhere where we could rent a room, because we had wives that were coming in. We found one home they had a room for rent, it had twin beds. Another home had a room for rent and it had one single bed. And so, we flipped the coin to see who would get which room. I got the room with the double beds. Anyway, we were training hard then, they were really pushing us then. My wife came down to Florida and we were together there. Of course I got to see her about every other night, because every other night we were flying 4 hours in addition to working for 8 hours during the day. So, we trained there and we went to maneuver over in another air field for several weeks and then went to Fort Knox, Kentucky for more maneuvers. In the meantime, my wife went back home. In Fort Knox, Kentucky we sped up, the ground crew went to catch a boat and we went to the air crew. The air crew went to pick up airplanes in Selfridge Field, Michigan and we went there and picked up 56 B-26 bombers, brand new. And so we loaded up there with the crew. We flew down to somewhere in costal Georgia to get all of our shots and everything and we were getting prepared to go overseas and then we started. We carried those 56 airplanes through to England as a group. 56 airplanes as a group. And that was quite a trip. We started out, first night we landed in Norfolk, Virginia, I believe. Spent the night there. Flew from there [to] Presque Isle, Maine. We could see New York City over to our left in the harbor, but we were out in the ocean to bypass that. We went on through Presque Isle, Maine and that was the jumping off place. We stayed there a couple of days and then we started. Next night we went to Goose Bay, Labrador and I’ll never forget the bay is shaped just like a goose and that was a marking for that place. We landed there, spent the night, refueled. We had to refuel at these different places. Then the next place, we flew into [was] Bluie West Number 1. That was Greenland and on the way up we saw a boat that had been damaged, and taken half of it out of the water and half of it under by the submarines, German submarines, that got in there, that got the boat. Then we saw another one that had been destroyed by submarines and we finally got to this airport and what they had done - this was a, you might say a god forsaken place in the world is up there - and they had, on the side of the mountain, they had made an airport, landing strip, right on the side of the mountain. We flew in and we landed right at the water’s edge. [We] went up a hill, up the hill a ways, and there was a parking lot for up there for about 200. Well we park 56 planes and it had a little bit of room left, but not much. But, we parked there and we intended to spend the night, but at about the time we got refueled, incidentally the sun just went around the mountain and came out the other side, never did get dark. This was in May I believe, but it never did get dark. Sun just went around behind the mountain and there’s mountain all around this bay. So, we had to - instead of spend the night - we had to leave. We were issued special glasses to wear. We flew across the ice caps which was about 200 miles of ice, I mean ice, ice. And the glare was so bad, we had to wear these special glasses and we flew from there to Reykjavik, Iceland. And we flew in there and spent . . . We were weathered in there and spent a couple of days, something like that, my buddy and I. Reykjavik was across the bay from the air field. We were at this airfield there. It was a big air field that the United States had leased from the country there. After sleeping for a day or two, we decided we’d kind of look the place over and looked down . . . About a mile, about a mile or two down the bay was a fishing village. And so we decided well we’d walk down there and look the place over. We were air crew, American air crew, we thought we were pretty hot stuff. So we walked down there and we got down there and of course this country, they were owned by the Netherlands. Some place in the Netherlands owned them, and the kids sic the dogs on us. We had to leave, we had to leave. Of course, we didn’t speak the language, but the kids sic the dogs on us and we came on back. We weren’t as hot as we thought we were. From there we flew into Scotland, from Scotland on down into England and our airbase wasn’t ready then. They were building it. They were a couple days from having it ready for us to go, so we slept under the wings of the airplanes for a day or two until we got to go to our base. I lived on this base all the time I was overseas. And I flew my first mission. The English would not fly at night on the Bombers. They said it was too dangerous. They use darkness, night flights, for the bombers. Of course the fighters would fly during the day. But B-17s were doing a lot of long distance flying then out of England. We didn’t have enough fuel, we could only fly for about 5 or 5 and a half hours, something like that was about our range. So we flew to France, Belgium, Holland, edge of Germany, and that was about what we covered. We flew a lot in France. At that time the Germans had already taken over the French, taken over France. They had gathered up all the guns. The Navy people had no guns. Of course, [the French] were under German rule. Our instructions were the French people that were real dedicated to France, that was [French] underground. I don’t know if you’ve ever heard of the French Underground or not, but the French Underground were very powerful. They didn’t say anything, didn’t tell anybody anything. When flying over France, if we were shot down, our instructions were don’t look for the underground people, they would come to you. One example, one guy was shot down and it was a place where we were bombing and he tried to land too hard with his parachute and he busted his ankle and he was just laid out, he couldn’t go even down. When the Germans started gathering up the damages, what have you, they gathered him up, they thought he was a German carried him to the hospital. Of course, bombs exploding all around you, he was covered with dirt, couldn’t tell by his uniform who he was or what he was. And anyways, they changed him and put him in a hospital gown. So the next day, he said I’m in the wrong place and he talked to himself. So one of the orderlies was French and was very friendly to him. So he told him, “I’m not from Germany, I’m from America, I’m an American and I was shot down over there” and this orderly said okay. That night, at midnight, he moved [the soldier] up to the back door of the hospital. The underground picked him up, carried him to a French home and got a French doctor to take care of him, take care of his needs, and so he would take care of him. Oh yea, when they flew, the last thing they did getting ready to go on a mission would be go by the parachute room and pick up a parachute and then we would also pick up an escape kit. In this escape kit was a little rubber coated bag. It was sealed up. In this bag was 2500 dollars in gold franks, wasn’t what the Germans paid, gold franks in 2500 dollars. Also, there was two tilt maps of the area. Also, there’s a compass and several other things in there, not much, but it all [fit] in a rubber bag. We were issued this bag along with our parachute. Of course, if you weren’t shot down and you made it back you had to turn that bag back in, because they were really close on that. But if you were shot down, the underground would contact you when it was convenient. And you were instructed to ask no questions, give them your money, and they’d take care of you. And so that’s what we did. That’s how we financed the underground in France. And also, some of us wore pistols. Not everybody, because I had so much junk I didn’t want a pistol. Oh flying over the water you had to wear a Mae West, you had to have your parachute with you. I wore a parachute harness, but my parachute was back here behind the copilot’s seat. Also, we finally learned that the safest thing was to take the steel helmet that we had, we pulled the liner out of it, take the steel helmet and we could put it down over our head. We had head phones on and what have you, and we’d pull it down over our head and we’d protect our brains. And also we’d wear a black suit and this black suit fit over your body, but it had no arms, no sleeves. But it was made out of steel mesh. Your black suit was a steel suit. You had so much on. Of course, we didn’t worry about our legs and arms, they’d stick out because they could replace a leg or an arm, but they couldn’t replace the body as well. Some of us carried guns, but our instructions were that if you carried a gun, be sure you had it full of ammunition and when you get shot down, give the French person, contact person, give him your gun, because he didn’t miss. That is good for 10 dead Germans. And if he had a gun, he didn’t miss, he’d kill. So, that’s how the guns were gotten back into France. Oh, I flew my first mission August the 15th on a Sunday morning about 9:30. We bombed an airfield in France and incidentally our assignment - our thing that we were assigned would eliminate, do away with, the German air force and, believe it or not, on D-Day the Germans only had two airplanes to put up against us before we landed. But they could shoot, they could shoot. That gun that they had, they could shoot and it was good. If we were in territory within range it took them 17 seconds to shoot, to spot us, and to put a shell up to us at 12,000 feet. Every 15 seconds we would change one of three things, either direction or speed or altitude. Normally, change direction about 10 or 15 degrees and we lived on that two seconds and when that happened you could look out the window and there was four shells, boom, boom, boom. Put them there for you, but you just happened to miss them. But they could really shoot. S/L: I just wanted to know what conditions were like for you during the war? Moody: Well, they were pretty good. Being a senior general of Eisenhower’s supreme headquarters. I found out that’s the man they were after, everywhere we went, they’d bomb the dickens out of it. We’d be on the train, they’d bomb the tracks out and send the jeep out and get us. All in all, like you say, we had some bad hours. Night and day, didn’t make no difference did it? S/L: That’s really cool actually. Do you have any stories, any favorite stories? Moody: Well, I don’t know. S/L: Did you have any friends with you? Did you make any like comrades, any friends with you during the war? Moody: No, not really. S/L: Before you entered the war, had you heard any stories about it? Like had anybody, any clichés or anything? Moody: Well, not much. I got back home when General Eisenhower died. They called my wife and asked me to come to the funeral since I was right in his staff, you know? I got home, why she said “well, I can’t go,” she said, “I can’t get my hair fixed, we had to leave the next day.” And for that reason, I didn’t go to the funeral, but they had planned to meet me in Asheville and I was going meet at the JFK airport. They had a seat in the church and everything for me. But he was a swell guy. General Eisenhower, I found out just a few years ago, the mad doctor that gave him his medication gave him the wrong pills and he died of the heart attack playing golf. S/L: That’s an interesting discovery. Did you have any expectations about the war before you went that changed whenever you got there? Like anything you expected that was different? Moody: Well wherever supreme headquarters was that’s where I was. Wherever General Eisenhower was, that’s where I was. But General Eisenhower said none of us would fly across the English Channel, that’s the roughest channel in the world. And we had to all go across in the boat. We sent all of our equipment, our clothes, my bullets and picture machine and a cameras and all that stuff, sent it all over in a plane. But we had to go, make the same trip at the beach, across the beach to the town, Normandy Beach, just like everybody else did. I got to see all the higher spots. I lived in hotel in France right next to Versailles Palace. I was there for two years. I guess I’m done. You don’t need anything else from me do you? S/L: Nope, unless you’d like to add anything else. Well it was nice to meet you, Frank. Unknown: Frank, I can take you home if you’d like to stay. Moody: Well, how much more time do you got? Unknown: I’m fine, just whatever the girls have. S/L: We’re fine. You can stay here as long as you want. Moody: Okay, looks like I’m staying. I’d be crazy to ride with a man with these pretty women around. Okay just carry on. S/L: Okay, what did you guys do for entertainment whenever you weren’t really working? Moody: Oh I liked music, always did like music. I played guitar and always liked to watch good musical shows on TV-- Lawrence Welk show and still watch it and Wheel of Fortune and Jeopardy. Dancing with the Stars is a good show too. S/L: That is a good show. We watch Jeopardy a lot. Whenever you came back, what was it like arriving back home after the war was over? Moody: Well, going over-- when I got up there to get on the Queen Mary, they filled the Queen Mary up, that big pretty ship, boy I just couldn’t wait to get on it. And they filled it up, and there was 22 of us that couldn’t go. They put us on a little train and took us to Boston, Massachusetts. We got on LST flat-bottom boat hauling ammunition and stuff over there. And we tossed on the [sea]. The crew was so sick they didn’t know which direction we was going in. It took us 20 days to get over there. I thought well after the war was over then, might have got over there though, --talked to some of them fellows [on the Queen Mary] said you’d better be glad you got to eat and sleep with the crew, we had to stand in line all the time, soon as we had breakfast we had to get in line for dinner. Once in a while they’d get out on top of the deck and see out. Then after I’d come back, I thought well we get to ride back in an airplane, now that we won the war. I used fish on a pretty ship out there and it hit a landmine and blowed a hole right in there and sank. And I had to come back on an English fishing boat trip and didn’t have no beds. They had these hammocks, you know that you sleep in? I slept in a hammock for thirty days coming back home. Hoping we would get back home for Christmas, but I didn’t quite make it. It was about three days after Christmas before I got there. And there wasn’t no band to meet us or nothing. Usually, they had a band and a welcome committee, and we just had a few people who took us out and gave us a good steak dinner and put us on a trip to Fort Bragg. S/L: Steak’s not bad. Moody: I got to see most of the interesting places over there. I took a vacation after the war-- Switzerland, Italy, Rome-- and I got to go back and take my wife too. I knew the places I think she’d like to see, so we enjoyed that trip back that way. And when I got back home I retired from the Dayco Plant in Waynesville and from there on it was do what I want to. S/L: So, what was it like coming home for you? Murff: Coming home? Or just? S/L: Coming home to America when you got released from the war? Murff: When I came home, I came back but I was still in the service. I came back August 1st, 1944. And we were still at war. We were still at war for about a year and a half after that. So, I came back, and I managed to get transferred to Keesler Field, Mississippi. There I became an instructor on pistol, recruit shooting and pistol and that was about my service after the war. I learned quite a bit. A recruit with a pistol, of course the gun was used so much that they were pretty well worn, and they would jam occasionally. A recruit would get a pistol and he would come having it pointing right at you, and you learn--you don’t say a word to him. You reach and get your hand on his and get the pistol. Then you can tell him, you can talk to him right then, but don’t say a word when he has that gun in his hand. I made one mistake then, I kind of regret it. I had a student one afternoon. I’d only been back all of 2 or 3 months and right out of the war. And I had a young man that refused to shoot. He said it was against his religion, so he wouldn’t shoot the gun. And that just burned me up. I had just got back from being nearly took out or killed in the line of action, and he was refusing to shoot. And I told him, I said alright, well you won’t have to shoot, but there’s a 5 acre field right here and I want you to pick up everything that doesn’t grow. And, you know, he didn’t say a word to me, he just went to work, he went to work. I kind of felt bad about it then. And when they moved him on--I sent him on. But he didn’t complain at all about having to work, he didn’t. And I guess, well, I couldn’t understand why the draft board had sent him in there, but he refused to shoot. I was sorry I did [that]after it was all done. It really got to me, and I had just got home from war. But I ended up, oh-- I got out on a point system. They came out with a point system at the end of the war that if you had so many points, you were eligible to go home. They came out with that system, the first, I believe, of June, and I heard all soldiers with 170 points or more were eligible to go home. I had 168 points. I got to go home in July of 1945, and I had a job waiting on me. So, I went back to it. What really helped me was medals. You got so many medals for each month you were in service and different things you had done. And I had, let’s see, I had about 50 something points in medals. I had 8 BFs [?], I had 8 air medals, course I had longevity stripe. I had a three year stripe plus and so many months and then I had 2 DFCs. Medals really helped me get out. S/L: I was wondering, how had America changed from your time going over and coming back, like how did your hometown change? Murff: Oh, alright. On airplanes we did not have any jets, no jets at all. All my airplanes were gasoline engines. No jets, no jets in there. No cell phones. No TVs. TV wasn’t available back then. No cell phones back then. Most of your telephones were either-- operator had to push for it. And we had alcohol, but no drugs. We had no drugs in World War Two. And now its-- drugs are taking this county. That was a no-no back then. Moody: Yeah. S/L: Did you notice any changes whenever you got back? Moody: I got three battle stars, for going into two or three battlefronts, so that helped me get out earlier. I ended up with a good conduct medal. I behaved myself. And I had 8 air medals and 2 DFCs, so that really helped me out. S/L: Do you guys still have your medals? Moody: Oh yeah. Murff: Yeah. Course, what happens, you get the medals and additional medals, well I had 8 air medals and so, on my ribbon I had a bronze that represented 5, then I had 2 silver ones, that was 7. The medal that was separate was the eighth one. And then on the DFC I had the medal, and then I had Silver Star to go with it. Unknown: Tell them what DFC is. Murff: Distinguished Flying Cross. Two words that kind of help describe it was above and beyond. And you have to look it up to find out the technical. Unknown: May I rephrase the question you guys were asking about the change in the county? S/L: Yeah. Unknown: But I’m interested too. I think what they were asking is from the time you left to go to your service to the time you returned from war, did you see a change in the country? Is that what you were asking? S/L: Yeah. Unknown: So not from then to current day but just during that time that you were away during war, when you came back, were things the same? Were things different? And if they were, what differences did you see? Murff: Well, you came back, you couldn’t buy sugar. That was one thing that you couldn’t get. You couldn’t buy automobile tires. You couldn’t buy gas. When my wife and I married, we didn’t have any gas to go anywhere. We went to the neighboring Spruce and my aunt and uncle ran a hotel there and that’s where we went. But back then, gas was rationed. Moody: Food stamps. Murff: Food stamps. You had to have food stamps. You had to have a stamp to buy a pair of shoes. If you didn’t have a stamp you couldn’t buy it. You had to have gasoline. You could buy, I think the average family got about 5 gallons a week, something like that. Unknown: And all of that is because those resources were used toward the war effort, is that correct? Murff: That’s right. The war effort took everything. Moody: It sure did. Murff: First scrap, first glass. You couldn’t buy an automobile. You couldn’t get the parts for it. Moody: Washing machines, something they really needed. Women needed them for the children, but you couldn’t buy one of them without a ration card for a long time. I drove my… Murff: Refrigerator. Moody: Yep. Murff: You couldn’t buy a refrigerator. Just number of things you couldn’t buy. Moody: I come back with all these hash marks. I had 31 years in, and I had overseas four of them and the rest of them all marks, I know a good boy back home said “I bet you killed a lot of people didn’t you.” Being in the army that long, I said no honey I didn’t kill anybody, but I indirectly killed them just like people back home. Anybody that was supporting the war effort was helping kill people. S/L: Did you change as a person at all? Did your opinions change? During the war did you have opinions that changed, like did you change as a person? Murff: I still can’t hear you. S/L: Sorry. How did you change as a person or how did your opinions change after the war? Murff: Oh well, I got sorry for the little children over there. When we were eating at the mess hall and the German children would all be around there, climbing the fence, wanting something to eat. And I won’t ever forget that. We been real lucky in this country. Moody: In England, the children would chase us asking for chewing gum. The little English children, “got any gum chum?” “got any gum?” Murff: Yep. Moody: They wanted chewing gum. Murff: Yeah, boy, a piece of candy. Moody: A piece of candy, yea. Murff: Cigarettes, now there was plenty once you got out of the States. It was 5 cents a pack out on the ocean. We got over there and found out everybody smoked and had to get 50 cents a pack for them or we just about quit smoking again. S/L: So how did Europe compare to America since it was in the war, it had all the action going on, so it was pretty devastated. So, what was it like there? Moody: Well Europe was really, things were tight. Food was tight. Something sweet, you couldn’t get. I know in England they served brussels sprouts, that was something that they grew there, brussels sprouts. We got a lot of brussels sprouts. We did not get any fresh eggs. We got canned eggs and canned milk. Clothes, they were restricted on clothes. You could only buy so many clothes--A good coat, that sort of thing, hard to come by. And of course, heat, I mean, I was cold. Well, some places, but in my cabin we found a Waterman [?] stove out in the junk. Somebody had thrown it away. We got it up, brought it in, cleaned it up, and fixed it up. We were …in a hut [that] had 16 of us living in this Quonset hut. And we were issued a bucket of coal--that was about a 2 gallon bucket of coal.. one a week. And you couldn’t even build a fire hardly with that. My buddy and I, he was from Oklahoma, farm boy from Oklahoma, and we got out and we cut us some wood. The airport had cut down trees and what have you, and we found a bucksaw and we sawed us up some wood. In inspection one time, he came in and we had a half a cart of wood stacked right behind the clothes hanging. We had a fire roaring… just as warm as the sun. But we got out and did it. Of course, we managed to get a bucksaw and saw up wood and of course we hauled the wood onto Ashton’s [?] jeep at night after dark. And, of course, we had a few times we had to use that five finger discount. You know what that is don’t you? Ever heard of the five finger discount? Murff: Oh yeah. S/L: What is that? Unknown: It’s shoplifting. It’s not taking something that doesn’t belong to you? Moody: We gave it back. Unknown: You gave it back? Oh, okay. S/L: You’re borrowing it. Moody: We just used it a little while. Murff: Women had it hard then too. My mother and daddy they’d been at Fontana working on that dam, and I bought a house there. And that’s all we did have was the house. But she had to take this little girl everywhere that she went, and there wasn’t nobody around to take care of the munchkins. And the milk man didn’t leave the milk sitting at your door. You had to carry that gallon, find somebody that had a cow and buy milk. S/L: Let’s see. Do you guys have anything you would kind of like to add? Like any memories about the war or after the war? Or anything you want to talk about? Moody: I never did talk about the war. Unknown: Is there anything else that you want to share about the war is what she asked. Moody: It wasn’t fun. It wasn’t fun. Murff: People now ask you, they’d thank you for your service. I don’t hardly know how to answer that, do you? I couldn’t tell them it was a pleasure. Murff: Well if I hear that, thank you for your service, and I appreciate it, but I don’t have an answer for it. Moody: I don’t either. Murff: I say thank you, I appreciate you asking, but I kind of forgot about it as soon as I got out, got home, got back to work. I had things to do and children to raise. Two daughters and a son and we’re proud of them, very. Moody: Me too, let me tell this tale. I got killed in action on Normandy Beach. When I come back I was working at Dayco, and I ate dinner over there at the restaurant. This lady come out with the newspaper and said Moody you’re the first man I ever served that’s dead. And she had the picture of my picture on the front page of the paper as killed in action. So that was the first time I got killed. Then I got killed they cut off all my social security, my army retirement and everything else. I don’t know how I got killed that time. But that was three months that I never drew a dime. I got in here and talked to these veterans and people, they took me to go to Franklin. They said he’s not dead, I’m looking at him. The woman in Franklin said I’ll have to see him, and she had to take me to Franklin for me to show her my face before I could get my retirement straightened back out. S/L: Wow, Alright, well I think that’s it. That’s good. Did we say our names at the beginning? S/L: I don’t think we did. S: Alright well this is Shannon Grant with Mr. Frank Moody L: And this is Laura Selby with Randal Murff.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Randall Murff and Frank Moody are interviewed by Smoky Mountain High School students as a part of Mountain People, Mountain Lives: A Student Led Oral History Project. Murff, born in 1919, talks about growing up during the depression in Mississippi, Calhoun County. He talks about being in the Army and hearing about Pearl Harbor just days after he joined and what it was like when he came home in 1944. Frank Moody, born in 1918, talks about growing up in Cullowhee, joining the Army and being a senior general of Eisenhower’s supreme headquarters also known as SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force). He also talks about what life was like after the war.

-