Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (19)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- 1700s (1)

- 1860s (1)

- 1890s (1)

- 1900s (2)

- 1920s (2)

- 1930s (5)

- 1940s (12)

- 1950s (19)

- 1960s (35)

- 1970s (31)

- 1980s (16)

- 1990s (10)

- 2000s (20)

- 2010s (24)

- 2020s (4)

- 1600s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 1910s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (15)

- Asheville (N.C.) (11)

- Avery County (N.C.) (1)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (55)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (17)

- Clay County (N.C.) (2)

- Graham County (N.C.) (15)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (40)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (5)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (131)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (1)

- Macon County (N.C.) (17)

- Madison County (N.C.) (4)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (1)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (5)

- Polk County (N.C.) (3)

- Qualla Boundary (6)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (1)

- Swain County (N.C.) (30)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (1)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (3)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Interviews (314)

- Manuscripts (documents) (3)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (4)

- Sound Recordings (308)

- Transcripts (216)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newsletters (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Publications (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- African Americans (97)

- Artisans (5)

- Cherokee pottery (1)

- Cherokee women (1)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (4)

- Education (3)

- Floods (13)

- Folk music (3)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Hunting (1)

- Mines and mineral resources (2)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (2)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (2)

- Storytelling (3)

- World War, 1939-1945 (3)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Sound (308)

- StillImage (4)

- Text (219)

- MovingImage (0)

Interview with Dawn Gilchrist, transcript

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

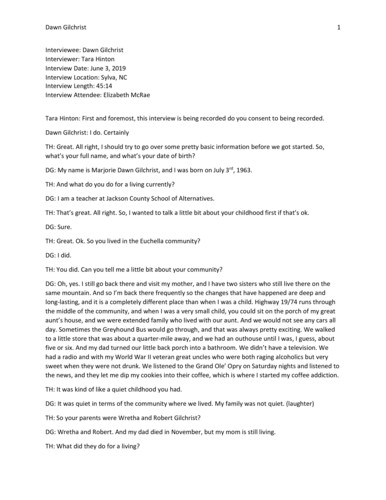

Dawn Gilchrist 1 Interviewee: Dawn Gilchrist Interviewer: Tara Hinton Interview Date: June 3, 2019 Interview Location: Sylva, NC Interview Length: 45:14 Interview Attendee: Elizabeth McRae Tara Hinton: First and foremost, this interview is being recorded do you consent to being recorded. Dawn Gilchrist: I do. Certainly TH: Great. All right, I should try to go over some pretty basic information before we got started. So, what’s your full name, and what’s your date of birth? DG: My name is Marjorie Dawn Gilchrist, and I was born on July 3rd, 1963. TH: And what do you do for a living currently? DG: I am a teacher at Jackson County School of Alternatives. TH: That’s great. All right. So, I wanted to talk a little bit about your childhood first if that’s ok. DG: Sure. TH: Great. Ok. So you lived in the Euchella community? DG: I did. TH: You did. Can you tell me a little bit about your community? DG: Oh, yes. I still go back there and visit my mother, and I have two sisters who still live there on the same mountain. And so I’m back there frequently so the changes that have happened are deep and long-lasting, and it is a completely different place than when I was a child. Highway 19/74 runs through the middle of the community, and when I was a very small child, you could sit on the porch of my great aunt’s house, and we were extended family who lived with our aunt. And we would not see any cars all day. Sometimes the Greyhound Bus would go through, and that was always pretty exciting. We walked to a little store that was about a quarter-mile away, and we had an outhouse until I was, I guess, about five or six. And my dad turned our little back porch into a bathroom. We didn’t have a television. We had a radio and with my World War II veteran great uncles who were both raging alcoholics but very sweet when they were not drunk. We listened to the Grand Ole’ Opry on Saturday nights and listened to the news, and they let me dip my cookies into their coffee, which is where I started my coffee addiction. TH: It was kind of like a quiet childhood you had. DG: It was quiet in terms of the community where we lived. My family was not quiet. (laughter) TH: So your parents were Wretha and Robert Gilchrist? DG: Wretha and Robert. And my dad died in November, but my mom is still living. TH: What did they do for a living? Dawn Gilchrist 2 DG: My father was a stone mason and a brick mason, and my mother mostly stayed home, and we did have a garden and a cow and a pig and chickens. My mother mostly stayed home, but sometimes when there was no construction work for my dad, which was pretty frequent in this area then. It’s nothing like now. He would need mom to pitch in, and there was a sewing factory, and there was a furniture factory in Bryson City at the time, and they’re gone. But my mom did short periods of working in those. And she also did a short period of time working in the elementary school cafeteria. Mostly she stayed home though and canned and raised children. TH: So again, it’s in your writing that you grew up kind of relatively poor. Is that correct? DG: It was clean, but we didn’t have a lot of extras. TH: But your parents still found the time and money to read and gather books. How do you think your parent’s love of reading impacted your life? DG: It changed it. If you look at studies on reading to children and reading, in general, you will see that the number of words that are read to a child and spoken to a child a day are almost directly commiserate with the level of education they will attain. And so, even though neither of my parents finished high school. My dad only went to sixth grade, and my mother only to seventh. But they both loved reading, and they came from families that loved… Well, my dad came from a family that loved reading. I don’t think my mother’s family did, but that was her escape, and so they always had books, and they bought classics. They didn’t just buy any books. They bought good books. So we were always surrounded by real literature. TH: Wow. That’s amazing. DG: It was amazing. It was such a gift. TH: That’s a rich childhood. DG: It was a rich childhood. Well said. TH: So, can you tell me about any rituals or traditions that your family had? DG: Probably… the one that I’ve written about is this ritual. The ritual of coffee and that was… and that’s one that I started with my great uncles, both of them World War II veterans, and they lived with us as did my great aunt. All of them bachelors. None of them married, and we had coffee every morning, and the children were given coffee just like the adults. It did start with my great uncles letting me dip a cookie in their coffee in the evenings when they read the newspaper. And that was probably when I was about two. And then the ritual of handing somebody a cup of coffee when they walked into the house and then that there was cornbread or if there was cake or pie then you handed that to them along with it. So it was a breaking of bread ritual and a drinking of excellent coffee. (laughter) I don’t know if it was excellent or not, but if you added enough cream and sugar, it was excellent. TH: So did you have any other traditions? Maybe did you read at night at all? DG: We had a family Bible study, and we didn’t do that always, but there were years when my dad was at home more or less tired that we would do it pretty much every evening. And my parents were very fundamental, and we read the King James Bible, and we read it out loud, and so that was my introduction to Elizabethan English, and that was early, and my sister and I were talking a few days ago, Dawn Gilchrist 3 and she said that she thinks that her interest in science came from the comic books we traded with some kids who lived close by. And I said, and my interest in Shakespeare came from the King James Bible, and we were talking about that. That was definitely a ritual or a tradition. We often got in trouble, though, because we all wanted to read out loud, and we often would read dramatically and not the way my parents thought we should. But we did read well—because of reading Elizabethan English. I’m trying to think if there’s anything else. Mostly the ritual in our home was work. And my parents both believed in that. And my father particularly was legendary for his capacity for work. I’d have to say suffering. He could work and work, and work was so hard, and he would come home, and we had animals to take care of, and so he would work some more. And we had a garden in the summer so he’d work some more. And we all participated. Not always willingly and certainly not cheerfully, but it was something that… it was just who we were. TH: Yeah. So would you say that your work ethic came from your dad? DG: I would say there is no maybe about it. It certainly did. And he used to always tell us the worst part about work is dreading it and if you can put the dread away, then work is just a productive way to fill your time, and so that’s been a good philosophy. TH: So, growing up, you had siblings, right? DG: Four siblings. TH: So can you tell me maybe their names [inaudible] DG: So Regina was the oldest, and she is now the science, technology, engineering, and math coordinator for Swain County Schools, and she has a specialist degree in education. And she still reads all the time and is passionate about public education like I am. And then I have a younger sister Camille who followed in my dad’s footsteps. She’s the beauty of the family, and she’s fifty years old, and she’s a stonemason. And I have a brother, Robert Duane, named after my dad. And he has an OSHA contracting company in Raleigh, and I have a younger brother Kevin Shane who has a construction company in Charleston, South Carolina. All of us were influenced by both of our parents, but three went into construction, and two went into education. TH: Did you have any experience in Swain County that really defined your life? Growing up as a child? DG: I said my family was noisy, and sometimes they were violent. There was a lot of violence that we saw. My solace was absolutely the woods and the mountains around the house, and so in order to have time that an introvert needs and I’m certainly an introvert. I would get up very early in the mornings if I didn’t have chores that I had to do, and I would walk, and I would go somewhere quiet. Sometimes I took a book with me but sometimes I didn’t. Sometimes I just took coffee with me or a jar of coffee. And so that became part of what I still need to this day. I still have to get outside, and I have such a love for the geography and the landscape here, and I think it deepens as I get older. So did it make me who I am? Yes. Could I have lived anywhere else? Yes, and I have lived other places, but I love this one the best. I’m Appalachian, certainly. TH: Yeah. Definitely. I read you loved art as a child. Is your family artistic? DG: Well, I think that my dad’s pieces came through in his work, in the stonework that he did. He kind of built some lasting monuments. Homes that he built in Cashiers and Highlands when construction really Dawn Gilchrist 4 began to boom here. And he began to do really well. He was very creative. My mother was very creative in terms of preparing meals from almost nothing them was nothing and loving beauty and the flowers. My mom still, to this day, her flower gardens are astonishing. So I think both of them were very creative. I have a younger sister that likes to draw. An older sister who likes decorating. And then both of my brothers seem to have an eye for beauty and aesthetics as well. So maybe it didn’t come out in terms of drawing or loving art, but it came out in all of us in terms of wanting to surround ourselves with something beautiful and appreciating beauty. TH: It’s a great place here for it. So I want to talk about high school and your higher education now. Where did you attend middle school? DG: There was no middle school in Swain County at the time. There was Almond Elementary School, and that was at the time that I was there, there was no kindergarten. We had Head Start, you know, a part of Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. And so we had Head Start, and after Head Start, which is in Bryson City, then we went to first grade at Almond School. That was first through eighth grade. So I was still at Almond School – it’s no longer a school - during those years. And now it’s an NCC extension school. TH: And then you graduated from Swain High School in May of 1981. DG: That’s right. TH: So how has Swain High School changed from when you went there to now? DG: It’s a lot better. I had two or three really good teachers, and they had an enormous influence on all the students who came through. Those teachers who were dedicated and passionate and really knew their content and were able to convey it. But there were not nearly the restrictions - and that was kind of a good thing – that there are today because the art teacher could take us to see all sorts of exhibits at WCU and even took us to Durham for a week for the American Dance Festival. So really wonderful things. So it’s much more restrictions now which is not entirely a good thing, because it means that teachers and kids can’t do as many things outside of class but even though I don’t love testing as a teacher and don’t love it for kids when they have test anxiety, it does create parameters that force people who might not otherwise know their content and convey it well. It forces them to know it better. So I think it’s much better. I think the pool is much better in terms of academics… stronger. Much stronger. TH: Thank you. So you once said that a great teacher sees more in their students than a student may see in themselves. Did you have any great teachers in college, particularly or high school, that really influenced your life? DG: I had great teachers all the way through. Maybe not at every level, there was always someone who as soon as they saw that you were interested and had that spark or that light in your eyes then they would… those teachers were are always the ones who would begin to make eye contact with you and then to talk with you after class, and then you ask questions, and then they began to say here is someone that’s curious about the world. I had many of those and too many to name them, though. But always at every level of my education, there was someone like that. I was really lucky. TH: How do you think that changed your life, having them? Dawn Gilchrist 5 DG: I think it fed me, and I think that because of where I came from and what I came from, I needed affirmation, and I think they provided affirmation until the point where I didn’t need it anymore. And then, I was able to turn around and give that affirmation to students in imitation of the teachers that I had had. TH: So, what was your favorite subject in high school then? DG: It would have been between English and Art, and History was a close second. And I wish that I would have loved science because I love nature and that would have been useful in my love of nature, but I just didn’t. And certainly not Math. But obviously, you do. TH: So you earned a Master of Fine Arts degree from Warren Wilson College? DG: Right. In poetry. TH: In poetry, yeah. That was wonderful. What motivated you to get a degree in poetry? That’s very unusual. DG: I did another master’s degree at a different school. I did a master’s degree at Columbia in Literature, and that was when I started really reading poetry and loving it. And then I started writing it some, and then the Warren Wilson degree came a few years later when I was in a transition in my life. I had left teaching at Rabun Gap Nacoochee School, and my daughter was two, and I wanted to spend more time with her, and so while I was teaching briefly at Western, I began to read a lot of poetry and write it and go back to my masters and think about a really good course I that I had on W. H. Auden and then I thought I think I’d like to get another degree and I’d like someone to write it. I didn’t think I’d ever be a famous poet, but I really wanted to learn the craft of it. And so it effected certainly my teaching strategy for understanding it. TH: You said you really love the craft of it. Can you elaborate a little more? DG: Yeah. I’d love playing with words and reading a line and thinking the syntax doesn’t work here. Everything has to be organic. Is there another word that would work better here in terms of rhythm and sound and meaning and finding those and then taking out one part and putting in another. TH: What or who prompted you to get higher education? DG: When I finished my bachelor’s degree, my family was very proud. I was the first one to get a degree, and my great uncle, one of the same great uncles who let me dip my cookie in his coffee and the other great aunt and the other great uncle were dead by then, but there was one left, and that was great Uncle Clyde, and he came to my graduation with my parents and the rest of my family, and after it was over he said now where will you go for you Master’s degree? And getting a Master’s honestly had not occurred to me until he said that and that planted a seed and so then I thought, why not? And then I had two really good professors at Western who had done their Master’s… they had done an MSA at Columbia, both of them. And so when I applied, I applied to [inaudible], and I applied to Columbia, and I applied to the University of Montana and the University of Victoria and wound up being Columbia, which was a great adventure for me to live in New York City. TH: Yeah. Definitely. So how if you lived in New York City… so how long was that? Dawn Gilchrist 6 DG: It was a Master’s degree, so it was… it’s too technical, but at the time, you could do your Master’s and then stop and then you could go on and do the Ph.D. Now I think you have to do both. If you get in for one, then you go straight through, but at that time, you could just do the Master’s, and I chose just to do that. So it was [two years]. TH: How did you think it was different there from here in the mountains? DG: Well, I had traveled some, so I had been in cities, but I’d never lived in one, and I was pretty excited about living in one of the world’s major cities. It was different in that the noise was constant and the flow and variety of people was constant, and I lived right off of Broadway, so there were people of every variety and everything you ever wanted, and everything you ever didn’t want was there. But I loved the liveliness of it, the smells of it, the smells of exhaust and food and urine and alcohol. They were always around you. It was vastly different. It was a different universe. TH: So you’ve been a teacher for many years. DG: Many years. Altogether, I guess if I count preschool. I took two years off like… anyway. After high school, I worked for two years, and I worked in preschool. So between that thirty-two years. TH: Thirty-two. DG: It’s a long time. TH: Yeah. DG: It’s a little more than twice your age. TH: So could you describe your experience as a teacher a little bit and the places you worked. DG: I worked after high school. I had no intention of going to college. And I was working at Southwestern Child Development, which is for… it’s a federally subsidized program that to this day still exists. So I worked with really poor toddlers and loved it. Not all of them were poor, but most of them were. And it was just fun, and I did that for a couple of years and enjoyed it and then wound up going to college and then taught at Randolph Community College. I taught English as a second language and taught people who wanted to get their citizenship, and then I went to Columbia, and then I taught at Rabun Gap Nacoochee School for four years, and then I taught ESL there. I think now it’s ELL, and I also taught English. And then at Western, I taught there, and then my MFA and then Swain. I taught at SCC for a little bit, and now Jackson County School of Alternatives. I thought about retiring last year, but I really… somebody told me about this position here, and I thought it would be really fun to work with kind of marginalized kids again, kind of going back to the preschool thing again. So, I’ve loved it. I’ve just enjoyed all of it. It’s been great. I’ve learned a lot. TH: Yeah. I bet. Thirty-two years that’s a long while. So, it seems that many teachers have a special skill that they teach kids like compassion or courage. Did you have one that you ended up teaching your students [inaudible]? DG: I think the fact that you said courage, I think one thing that I fed to kids over and over, and I got this from Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carry, his novel. And his novel’s about Vietnam. He says that courage is not something that you have instantly. It has to be developed and has to become habit. You will not be courageous if you’ve not developed the habit of courage. It’s something you do every single Dawn Gilchrist 7 day, and then when the moment comes when you need it, it’s there, but if you’ve never tried to develop that habit, it’s never going to be there. So maybe courage. Maybe. Although I’m probably known more for my kindness, but if I teach that, it’s only because I can’t help but be kind to kids I taught. TH: Yeah. If you teach courage or kindness do you do it by example, perhaps? DG: Kindness certainly by example. Courage, I don’t know if there have ever been any times I had to be courageous except being honest at all times and just hoping that my life is all of a piece. That’s kind of the definition. I would love integrity. But I don’t know if… I mean, I’ve never had to be courageous. Just being honest when maybe it’s not the most pleasant thing to do. TH: Are there any funny stories that you could share? DG: There are always funny stories in the classroom. Let me see. Probably the funniest trick a kid ever played on me was when I was showing the Zeffirelli version of Romeo and Juliet, and there’s a scene in it in which Juliet is nude, lying on her stomach, and I was a fairly new teacher, and my department chair said when you get to that scene, you have to fast forward through it. You can’t let freshmen watch it. And so I said ok. And I told my kids when we get to that I’m going to fast forward through it so when we got to it I fast forward it, and then it reversed itself, and then I fast-forwarded it, and it reversed itself, and I probably did it ten times before I looked at the back of the room and saw this little red-headed boy back there laughing till he was crying, shaking all over, and he’d brought his own remote so every time I fast-forwarded it he reversed it. So he rewound. I laughed really hard, and I gave him detention, and it really was the best trick any kid ever played with me. And another time, a kid posed as a substitute when I was out, and when the office checked through the intercom, he said the sub was there, and he skipped all his classes and stayed with my classes that day, and kids just loved it. Maybe not all my classes, but two of them before he was found out. And I’ve had some really funny girls who have told great stories, and I’ve had some bold, strong feminist girls who have just delighted me in refusing to be stereotypes for anybody. And you know these are just local country girls who just have some strength. And they always made me smile when they would step outside of what was expected of them. TH: How has teaching in a low-income area impacted you and impacted your students? DG: I think teaching in the low-income areas has made me more passionate about public education because I know how education has changed mine and my sibling’s lives. And I think public education, not to be too dramatic, but I think its kind of the last bastion of democracy. It is the ultimate leveling of the playing field if you have good teachers. If you don’t, then it’s the worst. And when I taught at Rabun Gap Nacoochee School, that’s a private boarding school, a lot of the kids there had all the resources they ever needed in terms of finance, maybe not everything they needed in terms of emotional but given the choice of where to teach I would choose this again and again. And maybe it’s because I like to be needed, and I feel like I fill a niche pretty well. TH: If you had to pick one thing about teaching what you love most about it? DG: I love it when a really tough kid who has not been able to trust anybody begins to see that I am predictably reliable and kind, and they begin to respond, and they open up just this much. That maybe I will listen and give you an opportunity, but I’m not going to give you much of a chance, so this it you better grab it while you can. I love it when I see that look on their face, and I realize that they are Dawn Gilchrist 8 beginning to see themselves through someone else’s eyes, and it’s not all bad. As a matter of fact, it’s pretty good. TH: How do you make the most of a kid [think that about themselves]? DG: I kind of begin to push things a little bit. Like I’ll write a note on the… They write a paragraph for me, and when I see them begin to read the comments that they write, then the next time the comment will be a little longer, and it will demand a little more of them, and then the next time it will demand a little more until finally it’s to the point where I can say you know you’re much more intelligent than this last sentence indicates. What can you do here to make it as intelligent as the first five sentences were in this paragraph? You need to fix it. And so I can ask more and more of them, and I can do it through their writing typically. TH: Well, I know that a teacher can take on a lot of different roles in a kid’s life. Do you have any stories about the time that you took on a different role that you played? Maybe having to feed them. DG: All the good teachers that I know, feed kids. We bring students food literally, especially if the kids are hungry. And a really good teacher in Charleston said to me once, you have to feed them in order to feed them and she was talking about the food before you can feed them academics. But I am very careful, and I have very strong boundaries and so except for feeding them food and contacting someone if I think their family’s in need - social services or something - I am only their teacher. And I tell them I am not your friend. I will not be your friend. When you’re twenty-one, maybe we’ll go have a beer but probably not. But I am your teacher, and I care about you. And I don’t tell them I love them. I tell them I like them. I set strong boundaries. I really don’t step outside the role of teacher. I did have one student tell me that I think you’re a human before you’re a teacher, and I said that that’s probably true, but I’m still not your friend. TH: So any other jobs that you’ve had . . . DG: I worked very briefly after I finished my bachelor’s degree in English for a con man, and he was writing get rich quick pamphlets. And he was asking each person to send him a dollar, and so and then he would send them all this information about how to get rich. And I guess people were falling for it and he needed somebody to edit them because he was terrible with punctuation and I saw the ad in the paper and interviewed, like for a second, and he said you’re hired but didn’t last very long. I realized what he was doing, and I was disgusted. So I did that. I worked in a furniture factory, cutting elastic for a little while also. I had a little grant to go study briefly independent study in Scotland, and it wasn’t enough, so I worked in a furniture factory cutting elastic until I had enough to back the grant. TH: So did you enjoy that? DG: Oh, gosh yeah. I was just there for a month. I was retracing the footsteps of Samuel Johnson and James Boswell. It was great. TH: So have you known that you wanted to be a teacher your whole life? DG: I just majored in English and loved it and knew I liked kids and then kind of fell into teaching when I again after when I came back from Scotland, I didn’t have a job, didn’t want to go back to work in the factory and I saw a job in a library, and there was another one at a community college, and I got both of them, and I took the one at the community college, and it was teaching ESL, and I loved my students Dawn Gilchrist 9 there. They were delightful. Even though I say I tell students I like them, I really do love them. I just don’t say it. But I did love these young women and young men from other countries who are working so hard to get citizenship. So I fell into it. I needed to feed myself and my husband at the time. TH: So I’d like to talk about your writing career. DG: It’s not really a career. I just write every now and then. TH: It seems like it is. You are a great writer. So, where is your favorite place to write? DG: It’s changed over time. At one time, it would have been sitting in a chair by a fireplace or a woodstove fire in the evening writing with a pen and a notebook. That’s where it started. But now I like to write sitting at my laptop in my study, quiet, listening to maybe some music that doesn’t have any lyrics so that I’m not distracted. That’s why I like to write by a screen door in the summertime so that I feel the breeze and get to look outside every now and then. TH: So in general you prefer quiet to write? DG: Oh yeah. I need quiet. I’m not good at focusing with noise. TH: What if any topic is your favorite to write about? DG: Probably public education and poverty. Those are my big passions. Sometimes the environment because I love this place so much and I want to protect it. TH: Yeah. That makes sense. How did winning the Norman Mailer Center’s High School Teachers Writing Award in 2011, how did that impact your life? DG: Well, it gave me kind of a platform to talk about students and Southern Appalachia and poverty, and I got to speak to a lot of wealthy people when I won an award because I had to do a speech and it was in front of lots and lots of lots of powerful people. So it gave that platform and then from that there’s this spinoff where I did interviews with Psychology Today and some different… and just little tiny pieces. But I got to talk about people here, and then I was able to get some grants for my classroom because… it looked good on a resume when I was applying for grants. People took it seriously. So it really… it fed my teaching. It fed my passion for public schools. TH: Would you say that writing is essential to you. To who you are? DG: No. I would not. And I think that’s why I would not say I have a career as a writer. I have two young colleagues from Swain from when I taught there, and one who just published his first book of poetry, and the other one is about to publish her first novel. And they both say for them; writing is pretty much like oxygen. It is not that for me. If something compels me to write, then I know I can, but I’m really not, I think, a writer. I think I am an observer. And sometimes I put it on paper. It would be more interesting if I said I was a writer. It’s far more interesting to talk to somebody who lives that solitary life and produce what writers produce but changes everything for centuries to come. But I just don’t think I am. Especially as old as I am now. I know I love to write at times, but I don’t have to write. TH: So you’ve been an advocate for education for a while. DG: I have. Dawn Gilchrist 10 TH: So in a 2018 editorial for the Smoky Mountain News, you said, bear with me, this is a long quote. “The harder we fight for those we represent, those children whose plight keeps us awake at night, the more we hear from our legislators that those children have little worth. Public school, even in the face of insult and injury, remains an institution founded on leveling the playing field for everyone — including the poor, the sad, the damaged, and the disabled.” How did the institution of public education shape you? DG: It allowed me to see outside my immediate family and to understand that the world was perhaps as large as my books depicted. And teachers who were willing to pay attention to the needs of their students and took us to places so we could see more of that world and showed us that it was available to us. That certainly shaped who I was and allowed me to branch out, and then it also allowed me to see how fulfilling it is to do that for somebody else. Through my love of teaching. TH: Sounds like it widened your world. DG: It widened my world. TH: What is your vision for the future? DG: Do you mean what do I think could happen to it, or do you mean what would I love to happen to it? TH: I think both, and then what do think you could change about it too, if anything? DG: I think that if the trend continues as it is now with financing public education, I think that in fifty to a hundred years it could be unrecognizable and gone. What I think that it could be wiped out. Toni Morrison said that a holding pen keeps the unwanted and unwashed off the streets. So I think it could become that if it is not supported monetarily. I also think that it has to become harder for people to become teachers, not easier. And then they have to be paid as if they were professionals, and then they have to have the credentials that any professional has to have. They have to continually upgrade their knowledge of their content as well as pedagogy. So I think those two things have to go hand in hand. Teachers have to be paid a lot more, and teachers have to find it very difficult to get into that profession. I think that our profession needs to be one that is as hard to get into as the medical field. But then in Northern Europe and particularly in Denmark, it is that, and so teachers are the best of the best. The result of that is students who come out with a top-notch education. So those are things I’d like to see. I wish that would happen, and if I had any say at all in it, we’ll move incrementally in that direction, at least in my tiny little sphere of influence. TH: So you think better teachers make the world a better place? DG: Oh. Yeah. I think without a doubt. TH: Also several of the articles you’ve written about the importance of art and funding for the arts in the school system. So what do you think needs to change for that to happen? DG: I love the United States, but it is not a country that has moved far enough along to love art or intellectuals. I love… What I love about it is that it can do or used to be a can do hands-on kind of country where people culturally believed in the value of work. I don’t know that that is still true today. I’m not sure what’s going to happen. I really don’t have a feeling of where things are going, but I do think there are still people who love the arts enough and who love culture enough and who think that it Dawn Gilchrist 11 is worth fighting for, that it’s not… I don’t think it’s going to die, and I don’t think funding for it is going to die in public schools. I don’t know what’s going to happen. You see the pendulum swing politically. And pendulums always swing politically if you look at science back and forth. And so now we’re kind of in a place where I don’t know if cuts can go any deeper in art and things for the poor without ending it. So I’m hoping that the pendulum will begin to swing back, and then it won’t end. That was a very long answer. I had to really think my way through it. TH: Is there anything else you’d like to add to this interview. DG: I think it’s delightful that there is a group of people who are interested enough in preserving what other people think and feel that you would bother to record it and take your time to do so. And I feel like it’s such a… I feel like almost awed… An interview is such a one-sided affair, so I know nothing about you and all those questions you asked of me. I’d like to throw back at you the ones that would apply to your life. The only thing I’d like to add is, why are you doing this? TH: Well, I think like you said, it’s important to preserve what people think, because history [we should keep it], and if we preserve other people, we preserve a part of ourselves and maybe we can look back and remember it, in short. DG: You said that very well. My husband… I don’t know who he’s quoting, but he often quotes, when a person dies, a library burns down and I think that that’s . . . People carry all those libraries within them, so thank you for being interested enough to open a few of those books in those libraries. TH: Thank you. DG: My pleasure.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Dawn Gilchrist is interviewed by a Smoky Mountain High School student as a part of Mountain People, Mountain Lives: A Student Led Oral History Project. Gilchrist, a teacher at Jackson County School of Alternatives, talks about growing up in Swain County, her educational path, her career as a teacher and her love of writing.

-