Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2683)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (15)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- 1700s (1)

- 1860s (1)

- 1890s (1)

- 1900s (2)

- 1920s (2)

- 1930s (5)

- 1940s (12)

- 1950s (19)

- 1960s (35)

- 1970s (31)

- 1980s (16)

- 1990s (10)

- 2000s (20)

- 2010s (24)

- 2020s (4)

- 1600s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 1910s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (15)

- Asheville (N.C.) (11)

- Avery County (N.C.) (1)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (55)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (17)

- Clay County (N.C.) (2)

- Graham County (N.C.) (15)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (40)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (5)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (131)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (1)

- Macon County (N.C.) (17)

- Madison County (N.C.) (4)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (1)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (5)

- Polk County (N.C.) (3)

- Qualla Boundary (6)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (1)

- Swain County (N.C.) (30)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (1)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (3)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Interviews (314)

- Manuscripts (documents) (3)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (4)

- Sound Recordings (308)

- Transcripts (216)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newsletters (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Publications (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- African Americans (97)

- Artisans (5)

- Cherokee pottery (1)

- Cherokee women (1)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (4)

- Education (3)

- Floods (13)

- Folk music (3)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Hunting (1)

- Mines and mineral resources (2)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (2)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (2)

- Storytelling (3)

- World War, 1939-1945 (3)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Sound (308)

- StillImage (4)

- Text (219)

- MovingImage (0)

Interview with Ashton Woody

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

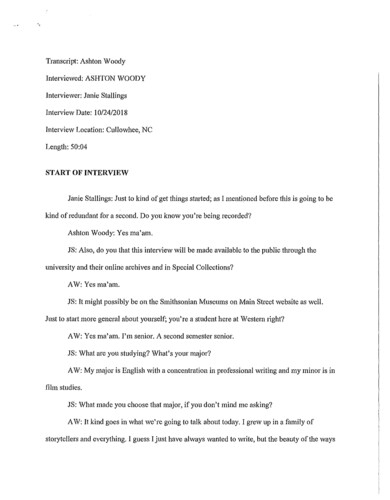

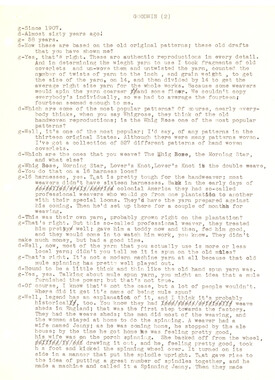

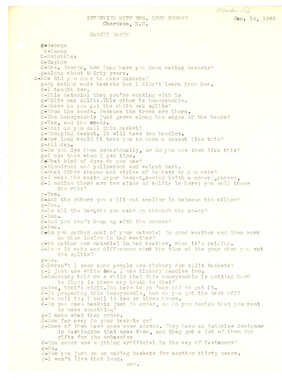

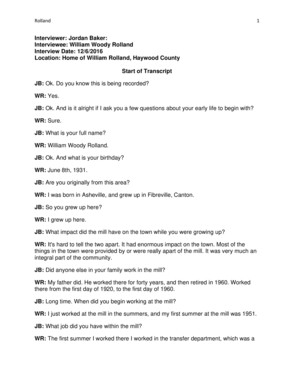

Transcript: Ashton Woody Interviewed: ASHTON WOODY Interviewer: Janie Stallings Interview Date: 10/24/2018 Interview Location: Cullowhee, NC Length: 50:04 START OF INTERVIEW Janie Stallings: Just to kind of get things started; as I mentioned before this is going to be kind of redundant for a second. Do you know you're being recorded? Ashton Woody: Yes ma'am. JS: Also, do you that this interview will be made available to the public through the university and their online archives and in Special Collections? AW: Yes ma'am. JS: It might possibly be on the Smithsonian Museums on Main Street website as well. Just to start more general about yourself; you're a student here at Western right? AW: Yes ma'am. I'm senior. A second semester senior. JS: What are you studying? What's your major? A W: My major is English with a concentration in professional writing and my minor is in film studies. JS: What made you choose that major, if you don't mind me asking? A W: It kind goes in what we're going to talk about today. I grew up in a family of storytellers and everything. I guess I just have always wanted to write, but the beauty of the ways Ashton Woody 2 stories sound- I don't know if this is the concrete reason, but it's the only reason I can figure, is I've always like the sound of beautiful, meaningful words and I've always wanted to write specifically poems. And being a poet, when I found that there was no specific poetry degree, but there was professional writing, which actually covers technical writing such as proofing documents, which is good for the work place. Also, I had the opportunity, and it counts for my major and take classes on poetry, literature and stuff like that, so it really, I don't know, kind of beefed but the way I could right. I think, definitely, it improve the way I wrote, gave me a lot more knowledge. JS: With you going to Western here; are you from the area? AW: Yes ma'am. I am from about an hour away in Swannanoa, North Carolina, about five minutes outside of Asheville. JS: What is Swannanoa like? Cause I'm not from here. I don't really know the area too well. A W: Swannanoa is where my family's been, Lord, for at least a hundred years. We've been in Western Carolina for tlu·ee hundred, but my mom's side of the family is all from Swannanoa and Swannonoa used to be a mill town. There was a place called Beacon Blanket factory, and everybody worked there and now it's kind of just a microcosm of what's happened in post-industrial America where we have no industry except gentrification. People that are not from there. People that take the old housing and make it really unaffordable, and a lot of people don't actually live in Swannanoa proper anymore. Beacon village, which was the mill village, is inhabited, but decreasingly less. Back in the day that was the good place to live cause that meant you had a job at the mill and could afford the housing, but my family lived in a small farm in a place called Patton Cove, which was up above Swannanoa. It's in a holler up above Swannanoa Ashton Woody 3 and it used to be pretty rural up there and it kind of the rough pmt of Swannanoa. You didn't live in Patton Cove unless you were a recluse or you couldn't afford to live in the mill village. Patten Cove today has a lot of the same problems, but none of the original families are hardly ever up there. My family and about two more are the only ones from when it was first, I guess you would say settled in the nineteen forties, fifties. JS: You mentioned right before we started recording that you were a storyteller and you play music as well. When did that start for you? If you want to go with the music route or the storytelling, or both, whichever? A W: They both started about the same time. I've always been a storyteller. I've always been a joker. I love it, but as far as to where I knew that that's why I've been put on the earth is the woman who raised me. Who was in Swannanoa. You'll here me mention speak a lot about her. Her name was Alice Silver, she's my great-grandmother and she was born in nineteen twenty-six, and her way of expressing the world was stories. Whether they be from her life, retelling stories from scripture, such like that, she saw the world as a story. Just like so many of them did and she was the first literate generation in her family. So to her, she had the benefit of writing, but she was very much in that old world where you told everything. The music that I was exposed to around them was, the just called it old timey music, and it was actually what we call folk, it wasn't even bluegrass. It was older and it wasn't country, it was older. Although there was the beginning of it, she like Kit Tanner and Skillet Licker and stufflike that. Very early Nashville country music, but we do it more folk. I'd always listen in on stories and I was also a horrible poet, I don't know if I'm a good poet now, but I was a horrible poet for a long time cause I just focused on trying to be like other people, but I knew it wasn't me. It was kind of a reaction, coming into it, all through high school I was more and more comfortable in my own Ashton Woody 4 skin: the way I spoke, my accent and everything else cause they made fun of it for a while. It was living with her all those years and, in a way, it was a way to connect with myself but also to, in a way, just like my mentor, be like her. So I started telling stories about my life, not so much invented things. I started taking inspiration directly from my life or her life or people I knew's life and doing what she like did, just spitming a story about it with dramatic elements. Every store is not exactly like it happened. In the south we exaggerate. We make it traumatic like a movie and I started with that. Senior year, as I had not started professionally telling stories in any degree, but just stories about my life cause I've lived and done wild things. People wanted to hear them and I could hold a classroom's attention, which got me in trouble a lot in high school. I told stories and everybody would want to listen and I can't help it, but I like telling stories so I'd get in trouble for it. Senior year I had to do a senior project and I was really getting involved in my past, my cultural past, and I wanted to do a carpentry project. I wanted to do specifically Appalachian carpentry and grandfather, who's been a maintenance man, hardy man, woodworker, part time blacksmith for a while, a long time. This is the woman who raised me's son, my grandfather. He, on my mother's side, he taught me a lot about carpentry and as we were doing this I realized that the music I was listening to couldn't do it for me anymore. I used to listen to a lot of rock, and I still listen to some and I listen to rap, which is what I listen to a lot now, but the main thing I had never listened to, other than those old records Mamaw'd talk about. I started actually listen to them cause she would mention them in conversation, sort of listening to them and it was more real than anything I've ever heard. The only thing like it was rap because it's music of the streets, lot of the time it's music of the experience. I heard these recordings and I wanted to play music for a while, but it was all this smultsy rock music, but then Ashton Woody 5 I heard that and said, "this is a pure voice." Just like the rappers. I said, "I have to perform this music" and I got a hundred and ten dollar guitar my dad graciously got me from a music store in Asheville and it was a son of a bitch to play. It would make your fingers bleed to note the frets because the tension was to high, the action was to high and I got to where I could bang out some cords on it. That's how the music got started and I got really into what they call Piedmont Blues, which is a North Carolina, South Carolina, way on almost up into Maryland. It's for the Piedmont and it's even into Alabama and it's a ragtime influenced blues that is very intricate, but it's deceptively so. It's a lot of finger work involved and cord shapes so you get a very- You have to be good with your fingers, but you can get a lot of sound out of minimal cording and I really was intrigued by people like, he was a North Carolinian, well they debate. He might have been from South Carolina, might have been from North Carolina, but Reverend Gary Davis. Loved to hear Reverend Gary Davis and so that' how the music got started. Later I got into the Elizabethan ballads, which is where I still am. The deep history in the mountains. That's how the music got started. JS: One of the things that you said when you'r talking specifically about storytelling that I though was really interesting. You said before you realized that storytelling is why you were put on the earth. Can expand on that a little bit? I think that's such a great way to put it and I'm very curious as to what you mean by that. AW: I feel that my storytelling is a gift. From the divine, from God and it's something that I can do with ease. It's something that I, just like my great grandmother, can experience the whole world that I've seen through a story. It gives me a vehicle to hop in and tell the story, to give it motion instead of just, maybe, talking to someone and they'll make it into a story. I started the same time, was talking about Swannanoa, I started realizing that the people who I Ashton Woody 6 love and were friends with. People my family, people everybody laughs at, makes fun at. What I mean is, I was friends with the down and out, the people like me, the people didn't have no money. I was friends with the people who's living in the trailer parks, people that were living over in the ghetto in Asheville. These was the people that nobody What Ed to hear their story. The people that moved to this country trying to make a better life like my cousin's father, Hispanic-American, and these was the people and they're were ill knowledged because they were shut out or could not get in to the mainstream storytelling. Storytelling I say in the sense of photography, stuff like that, you have to have money to get Nikon cameras. These people were so story based, everything was a story. It wasn't, "man, I went down to the store." It was, "man, let me to you what. I was walking down there and I saw so and so and I looked at him and he looked at me." Everything was a story because, in a way, you life is what you're given. You don't have these opportunities so you have to work with what your givens which is just your day-to-day life and they were able to make it- still are these people, my friends and family, make it into something meaningful. A story and I fell that ifl can give voice to them and make their stories come out of my mouth sometimes then I've done a thing and I feel that it's a blessing to be able to do. I'd say that is one of the reasons that I'm on this Earth if not the reason. I think everybody is here for some purpose. JS: How has storytelling ... has it been a part of your time here at Western at all? AW: Yeah, I never told stories professional before I came to Western. My aunt who works for the Southern Highland Craft Guild at the Folk Arts center in Asheville, she knew of the Mountain Heritage Center and she knew I was on work study and she said, "Will you go apply there? I think you'd really like working there." I went over to HFR building when we were still there and Annalane was still the Collections Manager and she happened to be there and I Ashton Woody 7 didn't know they were actually going to move to the currently location of the library. I spoke to her and she put me in contact with Peter. The next semester I met him and got the job. They first put me to work in transcriptions, which is taking recordings of stories, and stuff like that, and writing out a document of a transcript of what they say because I'm very good at the accent. I speak it, I know what people are saying and they didn't have anyone at the time that could do that. At least there was not a position for that so they made a transcriptionist and it was through talking that I let them know, "Hey. I know a lot of these old stories and I know how to tell them. Ify'all ever needed me to tell for groups of people I could do for it." Peter and Pam, the two managers here. Pam Miester is the Director. Peter Koch is the Educational Director. They said, "oh well, we like that," and they did a trial event where they let me first, perform a ballad, which is Barbara Allen, for people and soon after I was able to perform Jack tales. Well rather, reserved that. I told J acktales first and then was able to perform a ballad, but it was a very conspicuous day for me. Less and less, I'm believing in coincidences. The day that I told Jack tales was the day that my great-grandmother died and I knew that was a sign that I got to keep doing it. It's been handed off and she's gone on and now my work starts. I knew that was a sign for that and I needed that day and I've never turned down an opportunity since, I love it. I am thankful for the Mountain Heritage Center for giving me the opportunity to perform for people. Now I go to schools all over the area and tell stories. Even I'll them here sometimes too for the heritage center and also, I tell them just from people want to here one. That's the primary thing, I just love telling stories and hearing other people's stories. JS: Sorry to hear about your great-grandmother. She sounds like she was an incredible woman. A W: Yeah, she worked hard in her life. She has it now. Ashton Woody 8 JS: Good. Yeah, definitely. You mentioned Jack tales and I've heard you mention that before when I've been in the Mountain Heritage Center before. I don't know what Jack tales are. Do you mind telling me a little bit about what those are? A W: Well, you already know one and that's Jack and the Beanstalk and everybody knows that one. What these stories are, just like so much of the culture of the mountains ... See I have a saying, and it's my personal saying, "because of the ways hills are the time doesn't flow right in the mountains." It gets caught up so we have things that die out other places or time moves on and what Jack tales are is on of them little pools of that time that's clogged up. A Jack tale is based on a man named Jack. He's everybody in a lot of ways, he represents everybody. Jack originates in the ... the earliest ones we have written down are, at least in print, seventeen hundreds, early seventeen hundreds, late sixteen hundreds, in England. Jack is a young man who is, I'll say it this way, he's a good trickster. He's not a mean trickster. He does things that are questionable but he always it to try to help himself or help somebody else either get out of a hard spot or do better for themselves. Jacks through his stories, sometimes it teaches a lesson. Sometimes its just funny. My personal favorite is Jack and the Magic Sack. That's one that I've made my own in a lot of ways. It's about trying to do what's right in the world. Jack gets worried about the bad things he's done in life and he tries to turn it around. He has salvation at the end of the story. Jack tales are that, they are, you could say fairytales, but they're. Well they're fairytales but they're not in anyway like a Grimm's fairytale. They used to be all over the place, but the only place they exist now is here. People, the last generation of storytellers, you know one: Gary Carden. I don't know if Mr. Carden inherited his storytelling tradition, but the last people before that inherited stories were people like Grey Hicks. All that Beach Mountain thing that was going on up there. The Hicks and the Hannons. They've been doing it since 1700s or Ashton Woody 9 seventeen-thirties and that's kind of how my family was. The Jack tale tradition ended right before my great-grandmother. She had heard them but she did not actively tell them. She would tell Jack and the Beanstalk but she didn't so much remember many of them. She remembered a lot of other stories, but like I say, her life was an entertainment. She would tell her stories about her or her grandfather, her father, her sister, stuff like that. I am an inheritor of it but I'm not. I'm an inheritor of stories but as far as the Jack tradition, no I didn't. I had to re-start. My family did tell them at one time. JS: Moving forward in life, cause you know you said you were a second semester student, as you kind oftransition away from Western and move on to wherever your life takes you. How do you see stories going with you? A W: Stories are always my was of interpreting the world. It definitely has impacted my poetry. I write in a way that is more like speaking instead of ... There is high language, but it's more the way of speaking thus I write more like I talk. That will continue to influence my poetry. As far as telling the stories, I'll have new things happen, always have new ways to interpret not only the Jack tales, but I'll have new ways of telling my own stories and the stories about me cause there's always new things happening. I would love to continue to tell the stories for people and I would also love to get some of them published at some point so they'll always be apart of my work in life. Things that I do, not necessarily for money, I do get paid sometimes when people fell like giving me money but that's not the point of it. The thing in of it's self is the reward. JS: When you tell stories, what do you want people to get from your stories? A W: I want them to feel a personal connection to these stories and I want them to apply what they would be like in the story or how it reminds them of something in their life. Cause Ashton Woody 10 really this is a personal, other people might have thought this way, but I have a personal theory about art that says it's just like a matrix in math. You have the brackets and you plug in yom experiences in the story and how does it relate to yom own life? What would you do in this situation? It's a way to filter your thoughts. To work out things, apply to how the story was. It doesn't have to be the exact same. It's a mechanism to plug in your thoughts, to work them out, and I want people to be able to plug their thoughts into the stories, to work them out, which is certainly what I've done. Even more so with music, I plug myself into the music. There's so many of the old songs that have helped me. Lonely tunes, I Due May, which is a Sacred Heart song. These are all hymns, let's see. Death of Queen Jane, that song, gorgeous. Just the feeling of the song, beautiful in a way. Remorse, getting over remorse, not remorse but mourning is ... It'll do something for you, it's like a burden's lifted off. That's kind of what I want people to feel. The end result, I want them to fell better or that a burden's been lifted. JS: With your music, cause I know you play music. What all instruments do you play just for a start? A W: Well, try to play a lot but, the only one's worth hearing in public is the guitar and harmonica. The banjo I can't do much on but I have one. I have a few others: a mandolin, a fiddle, but they rarely get played cause I'm not that good at them. I guess that's why I don't play them much. Guitar, definitely, is my main instrument. Harmonica, I really, really, cause it doesn't take much to play it. There's not much thinking involved, like Guitar, until you get it into muscle memory, there's a lot of thinking. Harmonica, there's a reason a lot kids have them, you can pick it up within an hour or two have it pretty well, barring advanced techniques, as your ever going to get at it. Harmonica is definitely little effort, much reward. Ashton Woody 11 JS: Do you see music .. Sony, I'm trying to figure out how to phrase this question. In relation to your stories moving forward, do you plan to do the same with your music? AW: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. One of the really important people in American folk music, a lot of people don't realize it, or they think he's kind of commercial, and, yeah, he made money off of it, but he did something very important, was Bob Dylan. He took the American folk tradition, and what the modemist poet said about ancient forms, "you have to it new." I think that was Ezra Pound who said that. Make it new and you can take the old folk format such as the chorus-less ballads, the ballads with no chorus just fourteen versus long of just straight talking with maybe a word repeated at the end of each stanza. Dylan's Hard Rains Gonna Fall, it's a ballad. I forget the name of it, but anyways, that's what I would like to do. I want to, like I mentioned at the stmt, not necessarily rap but the production values of a lot of hip hop. The way you can use the actual recording sound. The sound of whatever format it's on. Say if it's on cassette you can you that to your benefit, in crating a whole picture, even the sound quality goes into the picture. Folk has yet to do that because, in a lot of ways, people think that Folk is just this kitschy thing played the same way every time and it warms people's hearts. It can warm people's hearts, but you don't play it ... the old masters were always making it their own way. They took the base original material and morphecl it into their own and that is what I would like to do to my music. I will always play in a style that is reflective of how I learnt that old way, but I want to do new things with it and I want to tell new stories with it while very much being respectful and praising the past though we can't stay there because stagnation is death. I don't want this to ever die out cause it sounds crazy, but the ballad traditions, stuff like that, is a clear link all the way back to Homer. People like that and using the song to tell a stoty that is important to own people. I mean look at the Iliad, you can get a picture of Ancient Greece Ashton Woody 12 entirely from the Iliad. You can get a picture of the mountains entirely from the song like ... at least the character ofthe people of a song like Only Wise, the beautiful good and the dark parts. You can get something like that in one work, kind of like a poem. JS: Do you see your storytelling and your writing, and even playing music ... do you see that as work? A W: Yes, because work is a good thing. Work is something you got to put effort into and you get out something out of it whether it be payment or reward and I get both. Sometimes I get payment, in fact I get payment pretty regular form people. There's a lot of generous people in this world and that's a part of the reason I do it, but it's not near the main reason. For me, work is good. Work is what keeps the tools sharp, you got to keep using them. For me, going out as frequently as I can, telling stories just like a man who owns his own shop goes out every morning and he uses his tools and makes something and he gets reward out of that. Whether be payment or just the satisfaction of making a chair. That is work and it's not a bad thing, it's a good thing to work. For me, when I get in front of that stage, there's hours of telling it other people. And you'll notice, if you hang around the Mountain Heritage Center right before I give a storytelling, I'll tell anybody I can. "You mind ifl tell you a Tory real quick?" So I'll work it out and make sure it's not rusty when I tell in front of a storytelling audience and also, sometimes I just want to tell it. It is work in the same way a professional baseball player. Yeah it's fun, but he'll go out there for twelve hours a day and practice bating so he can make a home run. It's the same way, you got to put the practice in even if it's fun. JS: Where some of the places in the area that you perform your stories and music and things like that? Ashton Woody 13 A W: Well, I've performed at Blue Ridge School. I've performed at Sun Charter school. I have performed at the Mountain Heritage Dat festival. I have performed here at the Mountain Heritage Center. I have told stories back home just out and about, not for any professional capacity. As far as music goes, the only place I've performed in a professional capacity was on the street in Asheville. I do what you call husking, it's a polite way of saying street performing. I'll put down the cause, the guitar case. There's husking laws in Asheville, you can't ask for money but it's implied when you have a guitar case open. There's no law against people paying you but there's a law against asking and selling CDs. It's inferred when you leave your case open right in front of you that you get money. I haven't made ... Hell, I've only made a dollar fifty in my whole time performing. That's fine and that's also the fact that there's hundreds of these people and a lot of them are ... They're Folk musicians but I won't say how good they are or not all that good. Let's just say that maybe they need to do some work. They need to practice. I know I do. JS: I'm curious about audience demographic if you will. Do you ever ... When you're able to perform stories or music or whichever, that you get to talk to people both from the area and from outside the area? A W: For the most pmt when I tell for children they're mostly from the area. What I consider from the area is not. .. They're all from Appalachia in a way, but they're not a strictly the stereotype of Appalachia. There's a lot of Hispanics children. There's a lot of children from other parts of the country, but they're all born here and live here. Their parent's form other parts of the country, so they might not be in the strictest sense Appalachia but they're all mountain people. I don't consider them outside. What is interesting, and I think has a lot to do with Folk revival in the sixties, I have a lot of people from up North and out West, baby boomer generation Ashton Woody 14 that really like my stories cause I think it's what they first heard about in college in the sixties and seventies. John Biez and stuff like that they're hearing. What they, I think, is something they heard the sixties Vivian Newport[?, 30:46] or they might have heard people like that. Not meant people after the sixties or seventies ... it kind of fell out or wasn't fashionable anymore, discos and stuff were. I think that they see that and it startles them that someone new and young is doing it, but I've been honored to say that someone told me that, they said, "You're the spitting image of Ray Hicks." Ray Hicks was one of the greatest storytellers of all time, regardless of nation. He was from Beach Mountain, North Carolina and when someone told me that, that was a real honor cause you can't fake that. He lived on that mountain his whole life with no luxuries. He was the real deal just like my elders, the real deal. You can't fake it, your either are like them or not. It makes me feel good. To get back to your question, it's primarily school children living in the mountains and people of retirement age from other parts of the country enjoy my Jack tales. JS: In you're answer you talked about , especially like baby-boomers from outside the area taking such an interest in especially your stories because you are such a young storyteller as far as the tradition goes. How are you received? If this makes sense, ifi need to reword, let me know. Does that impact your storytelling any at all as in, maybe even relations with other storytellers or things like that, if you know. A W: Relations with stmytellers, do you mean like, do I meet people who are also storytellers doing this work? JS: Yes, and what do they talk to you about? Or how they view you? If that makes sense. Sorry that didn't come out the clearest. Ashton Woody 15 AW: No, I understand. As far as meeting new people, I can say that right straight off the bat, I've never met another storyteller in sense that they're telling the old stories. Like I said I grew up with plenty of storyteller that didn't know they were storytellers. They just tell these whole world, that was their way expressing their feelings and ideas, it's always a story. These children, they always ask me general things, just kind of funny things because, to them, it's how a story should be. It's complete immersion. It's not, "Oh this is an Appalachian folk tale." No, this is just a story so when the dragon is right above Jack and has his jaws open right above Jack's head he throws that sword in his ribs. They'll shriek and go "eww." And stuff like that, "nasty." I always tell them, and I can't divulge on interview whether it's true or not, I'll tell them I know Jack and Jack told me his story. They always ask me, "How do I find Jack? How can I meet him?" And I say, "Jack's really shy. You can't find him." That's a big thing, is they come be frustrated sometimes. They getaway and start laughing and shaking their heads that they don't want to say Jack's not real and they've got an adult telling them he is real, "I've met him. I' be talked to him. We know each other." That's always what they say. The people from outside the region, the people that are invested or interested in it and realize what it is. It's a story, it is part of a folk tradition, they'll ask very respectful questions. "How did you hear these stories? How do you get inspiration to tell them, to actually get on stage and get the energy to do it?" I'll tell them and some people, especially in Asheville, that just tourists stopping by and they're out window shopping. You'll get sometimes not very sensitive questions. They'll ask you, "oh, isn't this all dead?" And stuff like that. Or, "You must know somebody around here." It's like, "No, I am from here." And that's always kind of insulting, it's like, "we're not all dead yet." Mostly, to them, they look at it as an oddity, "What is is?" For the people who enjoy stories, they're the ones who have no knowledge of a Jack tale, they focus on the craft. "How do you do that? What Ashton Woody 16 does this part mean?'' Those are the questions I really like answering cause you get it. You understand it. It's just like going to see a movie, when you get done you ask questions and think about it. You don't look at it and be like, "wow that was an oddity. Aha!" What did you just see? What did you sit there for thirty, forty-five minutes hearing the story? What do you think about it? That's the type of questions I like. Sometimes I just get random and I guess sometimes it's my own fault cause I dress up usually when I tell stories depending on the weather. If its hot, I'll jut wear aT-shirt, I try to wear nice clothes. What I do and I don't like, and I know this sounds strange, but I don't like modern day dress clothes. They don't look good. You know how that is. You'll see all these dudes in their Sperrys and I like the slick leather shoes or the old boots. I like the vest, pocket watch chain. I have my great-great-grandfather's pocket watch I wear. I enjoy that. I get questions, "Son, why do you dress that way?" I like it. It looks nice. It's a job, I dress up for my job. JS: Kind of going off of that, looking at these broader stereotypes of Appalachia. What are your thoughts on some of the stereotypes that exist in society today about Appalachia in general? AW: Well, the first thing I'll say is they're media propagated. They are the equivalent of shows poking fun at Hispanic people and outright making fun, poking fun is too nice a word. They are still culturally acceptable because this is a minority and the most of us in this country aren't that way. It's the "other," it's okay to make fun of the other and I think from a place of somewhat ignorance. Really we are in the Information Age, it's from a place of just, it's going to sound mean, but stupidity. It's from a place of people not thinking. It's from a place that you're other and it's acceptable to talk down to you. It's not acceptable to talk down to anyone. You treat someone like a human being. I look at someone and they make a hillbilly joke or something Ashton Woody 17 like that, I just look at them and in a way I feel sorry from them. It makes me mad but most of the time I just feel sorry for them. I think, "Well, you're someone who has not got it yet. You have not woke up yet," and some never do. It's disturbing, and I've spoken to a lot of people that have dealt with discrimination. It's disturbing how much it's still funny. There's a difference between jokes between friends and jokes between someone in a group. I can make a hillbilly joke to my kin people. My friends, we're all the same, we're a part of that, it is our identity in a way we take the stereotype and flip it and we're like, "It's funny, all of us hillbillies with college degrees." We'll make a comment like that and we'll flip the stereotype and make fim of it. Friends of mine that are Mexican you know, "First generation immigrant and I got a college degree." We flip it on people like, "Yeah, we're real stupid ain't we? And we're real lazy ain't we? We're out there doing the jobs you wouldn't want to do." It's just a way to handle it. I don't get mad no more, very little, I kind of just cool down. My girlfriend lives up in Ohio, which is teclmically up north, and I've met a whole lot of people who are actually really understanding. I didn't expect it just because you're used to people, especially ifl sing in Asheville, tourists and stuff gawking at me, treating me like a caged animal. It's strange, when you're in someone else's tenitory they treat you mostly like a guest. At least up there, people are very respectable, polite. Sometimes people, I've actually had random ladies at the store be like, "I'm sorry, but I just love your accent," and stuff like that. It feels good, it might be strange for them, but they go for it in a kind way and that's everything. Kindness is really every thing. "Do unto others as you would have done to you." JS: I can relate to that. I'm originally from Georgia, you know where Chattanooga, Tennessee is? A W: Absolutely. Ashton Woody 18 JS: I'm about fifteen minutes south maybe. There's a town called Flintstone, Georgia. AW: At least y'all have a lot of vitamins. JS: Yeah, and dinosaurs. We're technically in the Appalachian valley, right a the foot of Lookout Mountain and all that jazz. I just moved here from D.C. where I lived for a while. It's really interesting to see the way Appalachia is perceived versus what it actually is when you're from the area. How do you see your music and storytelling, kind of in relation to- not necessarily creating stereotypes, but in relations to them? Are the a way ... A W: They're a way to shatter them. They're a way to shatter them because these stories contain every bit of the high drama that we see in works like the Nibelungen, such like that. We have a dramatic tradition that, in Europe, what's funny is, people like V augner and such, which don't care much for Vaugner, if you read about his personal life he wasn't that good of a person. That's neither here nor there, what these supposed high society people that were brilliant creators, but they were of a socioeconomic position where they could write an opera and have the knowledge to write an opera. It's fi.mny to me that they always, not always, but after the eighteenth century they turned their gaze, not to the ancient beautiful Greeks, which I love Greek history I could sit here and talk about it all day. They saw that as the only high culture, but in that time period they looked to the people around them and the folk stories and the stories of everyday people. They realized this is sublime in the old sense of the word, this is the sublime, it's everything. It's so much that it's almost inevitable. It's so beautiful and Europe, we have the greatest works over there, which are mostly based on, at least coming out of the romantic period. They were based on everyday stories in America. It's almost like we have yet to get there. We have people like Mark Twain and people like that, but as far as our high art we have in the past eighty years have gotten to people like Langston Hughes and the weary blues, using stuff that Ashton Woody 19 was in his life. The folk traditions and his people, making a commentary on the poetry, and using the form from that Folk fmm and actually putting it into a poem and making it in a way, not only a poems but the blues. That is excellent and a way to destroy the stereotype that is a group of idiots or its just, you know, they have no culture, they're just sitting there spitting tobacco into jugs. That's one of the reasons I'm so focused on the folk culture, even in simple stories like Jack and the Magic bag. You'll hear stories and hear glimpses of this culture even if it's not the focus. You'll hear about people herding turkeys. You'll here having to go to market. You'll hear about people growing their food and it's all the folk ways associated with that. That's a way to there's a culture here. There is wonderful- It also is a way to break racial stereotypes. Not so much in the Jack tales but in the stories, my great-grandmother was raised in a black community and they were all friends in the time period there was nineteen thirties and forties. What was the happening in the rest of the country then? I can't say, but at least in that little community there was no difference. It was just the people looking at each other as brother and sister. Helping each other, how it should be, how it's meant to be, and I think when hear these real stories and, not saying it was like that everywhere, but at least to say it was a more complicated picture than you thought it was. Stories from my own like, like I remember vividly, first day of high school I was in English class and even the teacher was in on this kind of, and she was from New York, most cosmopolitan city on the earth. There also enter my cousin, Daniel Compansano Gomez, was in there with me and he's half Mexican. We were sitting in class and walk in, nod to each other, I shake his hand and say, "Good to see you." I hadn't seen him in a year or two cause we went to different middle schools, actually about hour years so I shook his hand and everything and we Ashton Woody 20 start talking. People start asking, "how do you know each other?" I said, "this is my cousin," and the teacher come over there. She though I was making a mean joke, she thought that I was trying to make fun of this Mexican kid and it was like, "No! He really is my cousin." When you share stories like that, this typical narrow minded bigots in the mountains, when you share stories like that people have to go, "well, damn." You kind of breaking the molds. These personal stories and the Jack stories, just folk stories in general, telling them from a place that's informed, you can break those stereotypes. By living your life in a respectable way and an open way to people you can be the exemplar, and exemplars have always existed. It's not just in modern invention, there's always been kind and compassionate, understanding people. Every much of the Appalachian tradition as anyone else. JS: Before we wrap up is there anything we haven't talked about that you think is important? That you really to discuss? A W: I guess, we sort of touched on it but one thing I just want to make really clear is that for a lot of the old people the work was everywhere and what we consider work today was no work at all to them. I grew up in that way and to an extent I saw the end of it. I'm not going to get into what Industrialization has done to the culture in the world. I will say that the old ways, I saw the end of the agricultural way, and I myself, at five years old, was out tlll'ee on my knees in the garden helping sow. What it was to them, I think a lot of the art, it was ... today things that used to not be work have become work because they're so rare, there's become a market for them. I think that's why I get paid, back in the day everyone would had storytellers in their family. There had been no need. It's a symptom of what's happened and I'll say this, the art these people and was like a drink of cold water, it was a bit of shade for them. It was a rest, that's what I'm saying. It was a rest and it can be a same thing in this modern age, this nine million Ashton Woody 21 electronic devices flashing at you all day. People just being dispersonal to each other, impersonal rather, to each other. This is an oasis, this is a place for none of that. This is a place for just you and a person to have a moment almost outside of it all. You can have something that is pure human contact and human stories and I think that that, not just Jack tales. All over this country and all over this world the traditional folk way is such as storytelling, but especially storytelling, I do believe are one ofthe resources that can turn around a lot of the negative things in society. I really do, it's a community builder and a genuine community builder, not something that's sponsored by some company or something like that, not cooperation. People organically doing it themselves just like anything grow up out of the ground natural. I think that's goes right back into what I was saying. It's one of the reasons I got to do it. The more I tell it, the more I realize it, when I first started out I didn't realize it but now I've seen it first hand and I'll be doing it until I can't move no more. Someone else I hope will. JS: Thank you for doing this, I really appreciate it. A W: Oh, absolutely. JS: Very incredible. A W: I appreciate you letting me talk. JS: Definitely. I'm just so interested in how you view stories and and your music. What it means in your life but also what you see it doing, it can do. I think it's really incredible. AW: This is my last little bit to say but it's my personal belief that it's a blessing. I could not do it without divine help. I would not be here. I was born premature, I would not even be here. All the good things I do in my life I know where to give credit, I'll say that. [50:04) End oflnteniew Transcriber: Janie Stallings Date Transcribed: 11/29/2018 Ashton Woody 22

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Ashton Woody, a senior English student at WCU, discusses her experiences growing up in Appalachia as a musician and storyteller. This interview was conducted to supplement the traveling Smithsonian Institution exhibit “The Way We Worked,” which was hosted by WCU’s Mountain Heritage Center during the fall 2018 semester.

-