Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2767)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (19)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6679)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- 1700s (1)

- 1860s (1)

- 1890s (1)

- 1900s (2)

- 1920s (2)

- 1930s (5)

- 1940s (12)

- 1950s (19)

- 1960s (35)

- 1970s (31)

- 1980s (16)

- 1990s (10)

- 2000s (20)

- 2010s (24)

- 2020s (4)

- 1600s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 1910s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (15)

- Asheville (N.C.) (11)

- Avery County (N.C.) (1)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (55)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (17)

- Clay County (N.C.) (2)

- Graham County (N.C.) (15)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (40)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (5)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (131)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (1)

- Macon County (N.C.) (17)

- Madison County (N.C.) (4)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (1)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (5)

- Polk County (N.C.) (3)

- Qualla Boundary (6)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (1)

- Swain County (N.C.) (30)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (1)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (3)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Interviews (314)

- Manuscripts (documents) (3)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (4)

- Sound Recordings (308)

- Transcripts (216)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newsletters (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Plans (maps) (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Publications (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- African Americans (97)

- Artisans (5)

- Cherokee pottery (1)

- Cherokee women (1)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (4)

- Education (3)

- Floods (13)

- Folk music (3)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Hunting (1)

- Mines and mineral resources (2)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (2)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (2)

- Storytelling (3)

- World War, 1939-1945 (3)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Sound (308)

- StillImage (4)

- Text (219)

- MovingImage (0)

Interview with Ann Woodford

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

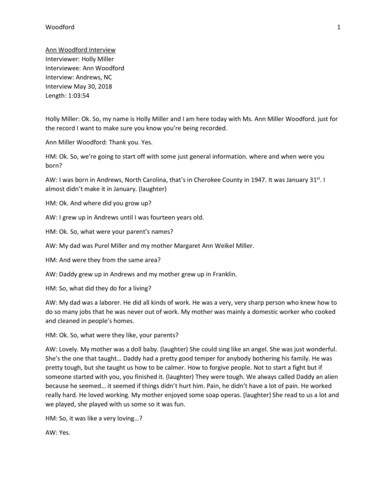

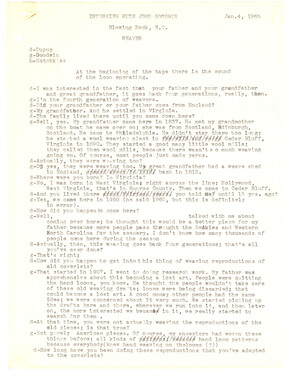

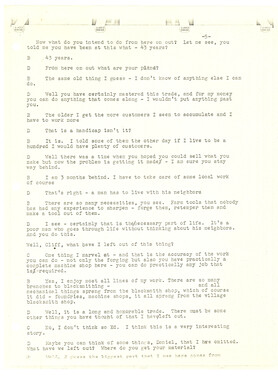

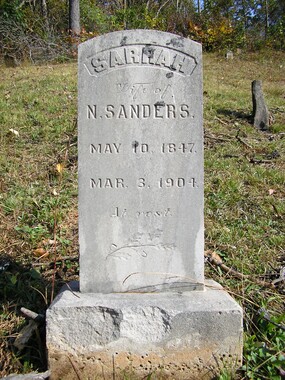

Woodford 1 Ann Woodford Interview Interviewer: Holly Miller Interviewee: Ann Woodford Interview: Andrews, NC Interview May 30, 2018 Length: 1:03:54 Holly Miller: Ok. So, my name is Holly Miller and I am here today with Ms. Ann Miller Woodford. just for the record I want to make sure you know you’re being recorded. Ann Miller Woodford: Thank you. Yes. HM: Ok. So, we’re going to start off with some just general information. where and when were you born? AW: I was born in Andrews, North Carolina, that’s in Cherokee County in 1947. It was January 31st. I almost didn’t make it in January. (laughter) HM: Ok. And where did you grow up? AW: I grew up in Andrews until I was fourteen years old. HM: Ok. So, what were your parent’s names? AW: My dad was Purel Miller and my mother Margaret Ann Weikel Miller. HM: And were they from the same area? AW: Daddy grew up in Andrews and my mother grew up in Franklin. HM: So, what did they do for a living? AW: My dad was a laborer. He did all kinds of work. He was a very, very sharp person who knew how to do so many jobs that he was never out of work. My mother was mainly a domestic worker who cooked and cleaned in people’s homes. HM: Ok. So, what were they like, your parents? AW: Lovely. My mother was a doll baby. (laughter) She could sing like an angel. She was just wonderful. She’s the one that taught… Daddy had a pretty good temper for anybody bothering his family. He was pretty tough, but she taught us how to be calmer. How to forgive people. Not to start a fight but if someone started with you, you finished it. (laughter) They were tough. We always called Daddy an alien because he seemed… it seemed if things didn’t hurt him. Pain, he didn’t have a lot of pain. He worked really hard. He loved working. My mother enjoyed some soap operas. (laughter) She read to us a lot and we played, she played with us some so it was fun. HM: So, it was like a very loving…? AW: Yes. Woodford 2 HM: Ok. And then what do you think that they, like, taught you about life? Mostly you said your mom taught you how to be calmer… AW: Mmhmm, Mmhmm. I think that Mama really taught us that you love yourself, um, so that you didn’t have to feel put down by people. Because when I was a little girl, kinky hair, which I had, black skin which I had, was not acceptable in many ways to people around. A lot of people in my community had lighter skin than I did, and so Mama taught me that you’re fine the way you are. Even though sometimes she called me a name or too. (laughter) She was angry. (laughter) And Daddy taught me how to work. I could build a house right now if I had the strength at this age, I could build a house because he taught me, all, how to use a hammer and saw and nails and everything I could do. I helped him build a barn and I helped him build a kitchen onto our house when I was just a little girl. So, I loved that. My life was good. Yeah. HM: And you said, um, you had sisters, right? Did you have any other siblings? AW: Just two sisters. My sister Mary Alice was two years younger than I. She was my protector in school because I was very shy and, um, kind of let people pick on me but she always said, “you don’t bother my sister” and she stood up for me that way. She was two years younger and then seven years after she was born my little sister came along. She’s Nina, lives in California right now. Mary Alice passed away of a condition called Sarcoidosis. And, so I have those two sisters and Daddy didn’t let us work, it was really something, because he didn’t believe girls should go to the field. HM: So even though you didn’t have any brothers he still…? AW: He worked hard on his own. By himself. (laughter) Yeah. HM: Um, so what are some of your favorite childhood memories? AW: Playing was great. We could play in the barn. We could play… we had a, there was a clay bank in front of our house, and we would pour water on the clay bank and slide down on our feet. (laughter) That’s a real fun memory. Being in the barn, just playing. We could play all the time. We made up names for ourselves and we played the imaginary family and played it all out and we loved our mother. We called one of our main play person that I was, that I represented was named Margaret Ann because we loved our mother so much. Yeah and it’s unfortunate and it didn’t have anything to do with Daddy but the man in it was called dirt. (laughter) Yeah. HM: Sometimes it happens. (laughter) Yeah. AW: And I don’t know maybe Daddy’s dirty clothes maybe that’s why we called him dirt. (laughter) HM: That’s great. AW: Yeah. Those were the fun times. It also seems like Daddy grew gardens so we would go in the summer when the carrots would grow up and everything. Take a little bowl of water and go down and sit in the carrot patch and pull up carrots. We’d take a salt shaker with us and we’d just sit there and eat carrots, rinse them off in the water and eat carrots right out of the ground. HM: So, you went to a one room, like, school for colored children, right? So, what was the experience like in that school? Woodford 3 AW: Good and bad. Okay, it was a one room, one teacher school. It was called Andrews Colored School for four years of my education and then Negro came into being and so it was called Andrews Negro School and then of course black… we changed it. People started calling each other African Americans and everything so now it’s African Americans. You rarely hear Afro Americans anymore. But that school had a big, warming stove in it. It burned wood and coal in there. We had to go to the outhouse to the bathroom, the restroom I guess you’d call it because it wasn’t a bathroom. But finally, about a year, maybe two years before I left there in the 8th grade they put an inside toilet for boys and girls which took up more of the room inside the little bitty room as it was. We were really squeezed together. But I guess there were fewer kids because my first year there, there were probably twenty some kids but the tannery in Andrews closed and when the tannery closed the parents had to leave and go somewhere to find work and so it meant that the children left with them. So our school went down, down, down in numbers. So, I think that the year after I graduated there were only twelve to thirteen kids left in school. So it was tough. For us that was a large number, but the school was very good for African American students that wanted it, that accepted it. Because they felt put out. The books that we received in the school were hand me down books from the white kids that had used up the, inside the book you had to sign your name, and it had been used up by that time so they used it as long as they could use it so they passed those books on to us. And that wasn’t good but our teacher, my favorite teacher went every year to college in the summer so that she would be up to date on everything. And they had a good education from… I think some of them mentioned Margaret Miller who’s a teacher here. She had her education and came to Andrews to teach and after that the ones that I had were all good teachers. There was this one that wasn’t that great for one year. HM: So, did it change teachers every year at the school? AW: Not every year. I had one teacher in the first grade, so it seems like every year almost. In the first grade that teacher left and then we had one for two years after that and one, one year and so the last four years I was there we had the same teacher who became my favorite teacher because she loved my art work. And on her own out of her own pocket she would send my artwork away to contests and I won gold keys from scholastic art awards and in the fair, you know, to enter my work into the fair and that encouraged me all the time. HM: That’s amazing to have that support. AW: It was. Yeah. Yeah, it was. HM: So do you think there were like any specific challenges that like were presented because it was such a small school? AW: Oh yes. Very much so. There, if the teacher hadn’t purchase things on her own even though she didn’t get paid less than the teachers in the white school, there would have been so many things we would not have had. We didn’t have anything like a projector to show films or anything like that. Books like I said, the books were old, but she made sure that we were updated because she went to school every summer. There… it was small. Small space. And one time, I think it was probably a couple years before I graduated, the maintenance people came in and painted our blackboard with enamel so you couldn’t even write on the blackboard anymore. (laughter) Yeah, yeah. So, things like that were real bad challenges and she would have to buy the big paper herself and write on it. One of the, the principal of the school, I guess you might have heard of Charles Frazier, the writer, the Cold Mountain writer. His Woodford 4 father was the superintendent. When he would come to the school, I think the school, I never did quite get it clear but I think that school was Andrews School instead of Cherokee County Schools. And so he was the superintendent and he would come and walk around and look at our work and kind of say some nice things about what was going on but we had a principal, I won’t call his name (laughter) but he would come in and he’d have his hands in his pockets like he was going to get dirty and so we didn’t appreciate him at all. We didn’t have a playground. A real good playground. It was so small that when you tried to play ball if you hit the ball it always went off the grounds. Sometimes it would go, when we would try, and the basketball goals were set up so close together that you… (laughter) Yeah. And so, the, um, neighbor didn’t like the ball to roll down into their yard and so often we couldn’t play anymore after the ball rolled down there. You couldn’t catch it and it would go down there so you had to wait until Daddy came home to go down and ask to get the ball. Another one, when the base, uh, softball would go across the field. The teacher was over there, and she said anytime just come on in the yard and get your ball. So, you always have these things. You know, I always say it’s like the two sides of my hand, you see? Things are like this, you know.., sometimes it’s good, sometimes it’s not so good. (laughter) HM: And you just kind gotta ride it out either way. (laughter) AW: There you go. You’re right. Absolutely. Yes. HM: Um, so after 8th grade the school was… there was no more school in Andrews. AW: Right. HM: So, you went to a boarding school in Asheville? AW: Yes. HM: So, what was that like? Leaving home and… AW: It was called Allen High School and it was the certified school, the highest level, private school. And I didn’t know what I was getting. The first week or two I was a little upset that I had to leave home because I hadn’t been away from home that far. But after that it was all uphill from there because I loved it. I made friends. I was living in a city rather than just in the little rural town of Andrews. I liked them both, so it was a great experience. Allen, at Allen High School that first year that I went there, there were 110 girls in the dormitory and that was good. So, the 110 lived on campus and then 50 some came from the outside campus and came for day school. We had what’s called duty work. So everybody, almost everybody, had to do… well all of us each had a job to do. It was sweep a school room or dust or do anything, something for duty work. And so that gave us some responsibilities. We lived from four… two in a room or four in a room. Nobody had a single room basically. But, in general the freshman had to stay four in the room and then as you got older you know maybe your junior and senior year you got a chance to just be with one other person. One of the neatest experiences for me was that there was a woman, a young girl from the Congo and they asked me to be her roommate because they wanted her… she did not speak English when she came, and they tutored her, the librarian tutored her everyday with English. But to learn how the girls spoke they wanted me to be there. They didn’t want to get too far down, ‘cause I was pretty, they could trust that I wasn’t going to teach her real bad language. (laughter) So I was her roommate and that was a real great experience. She taught me several things and I wish that I could be in touch with her now to see what’s she’s doing. Woodford 5 HM: Yeah. So, did she go back to the Congo after? AW: I’m not sure. See we graduated and I don’t know what happened to her. Her name was Esther [Essina] and I never did find out. And I asked… We just had a reunion and I asked, “did anybody know what happened to Esther” and everybody, “Yeah we’d love to know whatever happened to her.” But we also had two, three people from what was called Southern Rhodesia. And, there were two sisters and another lady from there and we had some from the Caribbean and so… it was all black though. All black girls. One white girl had gone there, uh, back when Mamie Eisenhower was the first lady and she had given her an award for taking a chance to live with black girls. (laughter) She got an award for that. (laughter) HM: So at the school was it like an almost improved from like the better funding, was there better funding for that school than…? AW: I’m afraid not. It was a Methodist Church school, so they didn’t have a lot of funding and it went down. By the time my sister who is nine years younger than I went there she was in the last graduating class from there. And so their funding was getting tighter and tighter and schools were integrated all around so it was like you don’t want to, the people didn’t want to give the money to run the school like that. It’s too bad it’s not existing now because it was such a great education. When I was there the girls that I, we had our little clique of girls who wanted to do well. So living in the dorm, you… after school and after dinner you went to study hall every evening and you had to study from 7-9. So, I mean, if you didn’t want to study, you didn’t study but you had to be in study hall. I’ll put it that way. 9:30, you had to be in your room and lights out. But the ones that I was friends with we wanted to do well so we would even sneak up in the middle of night and go to the bathroom and study for a test and everything. And I remember one time we had a big test coming and I was in the, one of the toilets, there were like, I think there were like three toilets there. I was in one, somebody else was there, there, and somebody was in the tub and another one was in the shower. We’re studying because we wanted to pass that test. So, it was, uh, a serious place where you really, really wanted to do well. And there is… she just clarified it but… Did you hear (about) the movie Hidden Figures? HM: Yes. AW: Um, one woman that went there before I went, uh, was at our reunion and she was one of the computers in the, in the background out there but she says, “I wasn’t one of those at that time.” But she came in later. But it was amazing the sharpness of some of the girls that were there. I mean a math, she tried to explain and I’m sitting there going, “Duh.” (laughter) But we, really… I had a wonderful, wonderful English teacher. And she was very strict. Actually, they were pretty strict people all together, but she was strict with us and I’m really happy because I wouldn’t have been able to write my book, When All God’s Children Get Together, if it hadn’t been for the fact that she was such a great English teacher. And so I’ve always been pleased that I had her. And those teachers lived, after the school closed down, they moved to the place in Asheville called Brooks-Howell Home. It’s a retirement center for Methodist deaconesses and missionaries and I visited them all the time because I wanted them to know just how much I appreciated what they had done. Yeah, and I went to their funerals and everything. Yeah… HM: Do you think that like it was hard being at a boarding school at such a young age? Woodford 6 AW: Like I said, when I went there, I thought it was going to be horrible and I cried for a whole week and the next week I probably got over crying a little bit and after that it was like, “Yay. I’m glad I’m here.” It was, it was really great. It was very strict like I said. They did things like, you didn’t wear pants to school or anything like that and there was a woman that inspected to make sure you were wearing a slip, so you’d go down through the hall, they had upstairs and downstairs and she sat in the stairwell and you came down she just turned your skirt up a little bit to make sure you had a slip under there and that you were clean. Your hair was combed, you were a lady. And, so it was very much, very important for us at that time to learn skills. I’ll tell you this fun little, one little story. Is it ok? Do you… is that okay? HM: Yes. That’s perfectly fine. AW: Ok. The principal was very strict. The superintendent was very strict. And every quarter we would have a dinner, a fancy dinner like candle light dinner and everything. So, we would learn how to go to fancy social events. So, this particular time it was the first quarter of my first year there. Sitting at the head of the table was the superintendent. Over there was the principal and here I sat across from them, right with them. Ok. Chicken was always eaten with your hands at home. You picked up a piece of chicken and you ate it with your hands. But they had this chicken… they had a plate and there was a whole like a half a chicken on one side. Noodles with gravy and some kind of veggie on the, you know, on the plate. And I looked at that and I saw these people with their knives and forks and I was like, oh no. (laughter) And down the table one of the girls tried and her chicken fell off on the plate and she was nearly in tears and I was like, “Uh uh. Ann’s not eating any chicken.” (laughter) So I didn’t eat mine. I just left it and ate all the noodles. They could tell I was hungry. Ate all the noodles and all the veggies and left that chicken on there, and like I said they were very strict. Well the principal was sitting across the table from me. Never looked at me. Never, you know, thought anything about it and just as we were leaving the table at the end of the meal the dietician came to the door and she said, “Ann Miller.” And I said, ohhhh what have I done? I couldn’t think of why she calling me. Went to the kitchen. The principal had told her to wrap up my chicken and let me take it to the room. Now is that love or what? HM: That is. AW: That’s really encouraging you know what I mean? So, we weren’t allowed to take food to our rooms, but she let me take it because she knew I wanted that chicken so bad. She probably saw the dripping (laughter). HM: The drool. (laughter) Oh my goodness! AW: That’s right. Yeah, so it was a wonderful experience. Also, when we took French, the first year… uh, that was my sophomore year. I took French and the teacher had lived in France and as a matter of fact she looked like you. She was just pretty like that, you know. And she had lived over there and she was nice. Real nice and she said “Everybody” … she probably gave us a little while to learn some words, but then when we had our dinner you could not ask for anything or speak at the French table. You had to speak in French so if you wanted the salt and pepper you had to ask for it in French. That was so wonderful because we learned, and my roommate and I, was my cousin who passed away, Lorraine Jones that lived…and she was of Crittenton. She and I would sit up there and try to speak French to each other, and it was just wonderful. The next year the lady came along because that one left and she said if you speak French in this class, I’ll give you a D. So, we had to learn it on our own out of a book reading, but we could not speak it. Woodford 7 HM: In French class? (laughter) AW: In French class. She’d give us a D. (laughter) HM: Wow (laughter) AW: So that was sad but when I went… in 2008 I had a sabbatical and it was a Z. Smith Reynolds Sabbatical and I had a chance to go to Europe, so I had a friend in Spain. She said she would travel with me so that I would be able to get around. She spoke languages like four languages. And we got to a station, like a subway station and someone had told us we needed to go west when we got downstairs and I saw it up there. I could read it. It said west. I said, “Come on Lydia lets go.” And she’s like, “Wait. No. No. I’ve got to find out which way is west.” I said, “This is. There it is. It says it.” (laughter) I didn’t realize that she could speak the languages, but she couldn’t read them. I realized then. I said wait a minute. I bought some art books and context makes a lot of difference so I brought the art magazines and I could read and understand what was in there and that takes me back to the fact that I had those two years of French and that I learned to read it a little bit. I didn’t understand all of it, but it was, it was pretty good. But I couldn’t speak it. HM: And you retained it like through? AW: Yeah. All those years I hadn’t even thought about it in between. But I was able to and she was like, “How did you know that was west?” And I said, “it’s spelled right up there.” So, we had some great teachers. The last teacher from Allen High School died last… I think it was last year. She was 101 HM: Wow! AW: Yeah and, but I didn’t know her as a teacher, but I got to know her through one of my teachers. Another great experience was that the choir director and the piano teacher was from Vermont and she took the choir to Vermont and New York and we traveled. It was my first time ever being out of this region. You know, ‘cause I had gone done to Etowah in Tennessee or some little places like that where family lived, but in those days they didn’t have the safety rules they have now so when we got ready to leave from Asheville to head… we had to go up through Washington D.C. and then go on up through New York. I stood in the well, the stairwell there on the bus for hours. I was so thrilled to get to see. And back in those days we went through Winston Salem and they had the cigarette packs, huge neon signs that were cigarette packs and I never will forget the way that looked and I was just “wow!” My mouth was open, my eyes. And Mr. Tebow was the name of the driver and he told me a lot of things because I could talk to him. Some of the girls were back there sleeping or whatever but I was like, “Whoa, I’m going somewhere.” (laughter) Seeing the world. So, we traveled, zigzagged for fourteen days back and forth across the borders of Vermont and New York. The day we got back was the day that President Kennedy was shot and that was such a horrible thing after such a wonderful trip to come back and hear that news. I heard some girl down the hall who had a radio, I didn’t have one, screaming and crying and I went down to see what it was, and they said President Kennedy has been killed. He was a hero for us. HM: Right. So, what was that like dealing with that? AW: Oh, it was painful. Because we were in the dorm because we were just getting back from the trip and the other people were over in the school building so they probably didn’t even know either because of being in class but it was painful because we believed that he would work with Dr. Martin Luther King Woodford 8 to give us rights. And we loved Robert Kennedy too and to have him killed, to have President Kennedy shot like that, you know, was heartbreaking and we cried for hours. It was sad. Yeah. It was painful. HM: So were your kind of nervous about Johnson taking over for him? Or… AW: I don’t think we were nervous, but we didn’t expect him to do better. (laughter) You know what I’m saying? We did not because he was known to have used the “n” word and… and he was tough. He was a tough, tough man. You know. HM: I think I asked my grandmother about it and she said he was a “rough cowboy.” (laughter) AW: He was. He was. Rough cowboy. And those words and all that he used and the way he ran people. He just ordered people to do things and it was so unbelievable when he said we’re going to have this right. People are going to have their rights and they listened. Thank goodness he was a rough cowboy. (laughter) Yeah, it was great. Yeah. HM: Ok. So, um, how was the church like a part of your life throughout like your upbringing and your youth. AW: The church meant so much and it still does to me because I truly believe I have the faith that is based on the way Jesus Christ walked and not on people and religion. I don’t… I can go to any church as long as their doing the way I feel Jesus Christ walked and so that’s my faith. And from a little girl I went, we always went. But our church services were quite different than you go to church now. Nobody shouts anymore but they used to get up and shout and scream out and run up and down the aisles and everything and it was not only… as a little girl., it wasn’t only a spiritual experience, but it was entertaining. We had a television. We got our first TV in 1957. When my sister was born Daddy got Mama a television for a thank you and reward for having my little sister. But before that we only had radio and so we were at school, at church and school. The school was right across the street from the church so when we have um graduation we graduated in the church and so it was a real cooperative effort and teachers were… I guess you’d call it equivalent almost to the preacher in respect. The preachers came from other places. Usually no one came from our community that was a preacher. They would sometimes travel as far as from Old Fort to Andrews. That’s a long way to travel. Coming up Old Fort mountain all the way across here and everything. But, um, my mom and dad always fed them. They would come to the house to eat after church and sometimes they’d bring a whole, huge… I mean too many people in the car just so they can eat Mama’s cooking. Mama was so good. But we learned, we learned the Bible there and we had fun. There was Vacation Bible School by white people that came to do Vacation Bible School for us. One of the black ladies in the community always taught Sunday school so we went to Sunday school. But we had church every other Sunday instead of every Sunday because the preachers had to come so far, and they would preach somewhere else on that other Sunday you know in between. So, it was a very good time and we had something called the association which is the Waynesville Missionary Baptist Association. Uh, my mom and dad met because of the association. Mama was on a pick-up truck she said coming from Franklin and Daddy was there and Daddy said when he saw her jump off that truck, he knew that was the woman for him. (laughter) HM: So, it was like love at first sight. AW: It was. Yeah. So, Daddy and Mama worked their way up to his, the woman who was his midwife had a beautiful yard and grapevine and everything and they worked their way up to the grapevine and I Woodford 9 guess Mama saw him too, you know what I mean, and it was cute. He was real cute. (laughter) When you look at the book you can see pictures of him when he was young. She was a pretty woman too, young woman. And he asked if he could come to Franklin to visit her and she said well you’ll have to ask Mama. So, when he asked her Granny said yes. And Granny and Grandpa really liked my dad and so it was fine. And they even, when Daddy would go over to Franklin, Mama had an older sister and two younger sisters and he, they would let Daddy take them. They could go for long walks and everything because they trusted Daddy, you know. And so that was a real neat thing. And a funny story is that my aunt, the older sister, Daddy took a guy that wore a uniform. He was in the Navy. Took him with him on the bus. They went over there together because I guess Daddy said, “Oh there’s some available women over there.” (laughter) HM: Cute sister (laughter) AW: Yeah. Right. Right. Exactly. So, Mama said they’re all on the porch and they see them coming and Uncle Wilburn, we called him Wilburn. She called him Garfield because his name was Wilburn Garfield McKinney. Aunt Mary Ellen saw him, and she said, “He’s mine, he’s mine, he’s mine.” (laughter) And they were walking from way down the road. Two weeks later they were married. HM: Wow! AW: And they had kids. They had five kids. He was in the, he…They got married and he was in the Navy and he went away and sent his money back and while he was gone his house was being built so they moved in when he got back from the Navy and they had their kids and lived in Franklin all that time until they both passed away. Now that was love because he died, and she said to me at the funeral. She said, “I can’t make it.” I said, “aunt Mary Ellen it will be all right. You know, I know that you’re grieving now but you can make it.” She said, “I can’t do it without him.” And two months later she was dead. HM: Wow. AW: Yeah. Some people are just like that, you know? HM: Yeah. They just know they need that person. AW: Yeah, that’s it. That’s right. But she saw him from a distance, and she said, “He’s mine. He’s mine. He’s mine.” (laughter) HM: And I guess he was. (laughter) AW: That’s right. That’s true. But the church has always meant a lot to us in the community. Bad things and good things happen at church. Sometimes it’s not the best thing, but you get over it because of the faith that you have. The strong faith. And my faith is that I need to… my mom taught me you must forgive people. They are going to do things that you are not happy with, but you have to forgive them. So, she taught me, and I saw her in action forgiving people that did things that were not, not good. And sometimes they were church members. You know, people that were going to church all the time. I think it’s just an important thing. That’s one of the reasons that as I was explaining in class that you can get through racism because you forgive people as a group. You don’t forget what happened, but you forgive, and you know as Mama taught that it’s not… everybody doesn’t think the way somebody that really mistreats you thinks. Whether that’s in the church. Whether that’s a black person or a white person who ever it happens to be. In our churches white preachers could come and they always gave Woodford 10 them the pulpit. They could preach. Cherokee preachers came. And so, if a strange preacher came, said he was a preacher, they let him preach so it was a… it was a good thing. But I remember one story about a white preacher who came and began to speak against Dr. Martin Luther King and Daddy just escorted him out. Don’t come here talking like that. (laughter). That is not acceptable in any manner. Yeah. So the church has meant a lot to me, to my family. We all…Mary Alice passed away when she was 40 years old and my sister Nina still goes to church in California. And I went when I was out there and that’s my friend from Spain that I was talking about. She and I go all over to churches, so it was a good thing. Yeah. So, it means a lot. HM: Ok. So… College. AW: Yeah! (laughter) HM: Where did you go to school? AW: Well, it was an amazing thing. I wanted to go to American University in Washington D.C. because of their art program, but they told me you need to apply to at least three colleges and wherever you are accepted. Well I was an honor student. So, there wasn’t much of a question that I would get accepted but it was just how and what would you get. What scholarships or whatever would you get. So I asked my dad for the money and the first application that came was to Ohio University in Athens, Ohio. I asked Daddy for the $60 dollars. He gave it to me, but I didn’t… was never… as a young person sometimes we don’t think of where that comes from because I wasn’t working. I mean I worked in the summer, but I wasn’t really working to make that money and so when my application came to American University I said, “Daddy I need $60.” He was like, “I already gave you the money. That’s it. No more.” So, I had to accept Ohio University and they gave me an out of state scholarship. I had something called NSSFNS, National Scholarship Service Fund for Negro Student Scholarship and all I needed to get into college was $600 and that was tough so I thought well Daddy will sign, you know, for a loan for me but he said no. And it happened that I was working with a lady, a white lady who had worked in Asheville in a bank and she said, “Purel you’re daughter needs to go to college.” And Daddy was just, “I know. But I’m not going to lose my home over signing some paper” cause that’s the way it looked… you know, and it could have easily happened back in those days. So she went to the bank in Asheville and told them about me and although they only gave loans to juniors and seniors they gave me one as a freshman. But guess how much it was for. I just told you right, $600. That’s all I ever had to borrow. The rest of the way through college I got full scholarships. HM: Wow! AW: Yeah! So, it was worthwhile to do it and when I, um, graduated from college I went to Pittsburg to work for an organization called Young Life Campaign which was the Christian non-denominational group and then I decided to become an airline stewardess. As soon as I did that, I paid that loan and I got married a year after that and he paid most of that loan off and that last few dollars. He paid it off for me when we got married. So, I never had any loans to have to pay years later, you know, like people do now. It’s really sad that people have to pay so much and end up working almost their whole life to pay off college loans. But it was a good school. I was glad that I went there, and I think I said to you all in the session, that there were famous artists who became famous or were famous at the time teaching there. And that was a good thing. And I had a lot of experiences with other races of people. Like there was a Japanese girl that was a buddy, buddy and the Chinese girl, a tall Chinese girl which was unusual Woodford 11 because most of the Chinese were shorter people, but she was tall. Her name was Pearl Lee Yang and I’ll never forget her. I want to try and see if I can find her too on Facebook or something, but Pearl was very, very nice. Always. She was a senior that year that I got to know her, and she was down the hall and always so nice and just. The social life there was good. Heidi Stefan was another person who was from… her family was from Amsterdam and she and I use to take ten mile walks all the way around the campus and way out into the country and everything. That was nice. And then I dated African men from Nigeria and that was a real experience. One of them wanted to marry me. When Dr. Martin Luther King was killed this, one was wealthy, his parents were paying his way from Nigeria. Others were there on scholarship or exchange. But he said, um, his father was paying his way and he always wore his national clothing and he was so handsome. Oh, my goodness he was handsome. And when I would go out with him to the movie or to eat or whatever he would send a thank you note. That’s why he was so nice. And, um, when Dr. King was killed, he came to me with tears in his eyes. He said, “my father says I have to come home. That he will not let me stay in a country that will kill a man like Dr. Martin Luther King and I want you to marry me please. Marry me and come with me.” And I was like I can’t drink all that water I’m not going…(laughter) I can’t leave home. So sorry. So, I’m glad I didn’t do that. I liked him a lot. He was very, very nice but I found out later that they said what happens is that the culture in Nigeria, the women that I met that were Nigerians as well, said that the culture was such that the man would take you home and give you to his mother. If she liked you, you had a really good life. If she didn’t like you, you might have trouble. So, I said oh I’m so glad I didn’t go. (laughter) HM: Didn’t want to risk that. AW: That’s right. Exactly. That’s right. HM: So, what exactly did you major in in college? AW: It was art. HM: Art. AW: But it was interior design. One of my teachers who’s still my friend lives in New York, Johnsonville, New York right now. She was from upper state New York and they had a big dairy farm up there and she was what they called a US-2 which meant she was in the Methodist church she would do two years of basic service and she came to Allen High School. And when she found out that I was going to… that I was accepted to Ohio U she said, “You need to decide what you want to do, what your major will be, and I know some people in New York that are interior designers. Maybe that’s what you would want to do but they are well educated people so you should go up there.” So, Christmas time my senior year I rode a bus from Asheville all the way up to New York, upper state New York, met the people and they convinced me that interior design would be a good major. So, I majored in fine art. So, my Bachelor of Fine Arts degree came from that. Fortunately, and unfortunately, I never really worked that long in interior design because it was a tough road to be treated well as a black person. I worked in the Federated department stores and as a black person it was like they didn’t trust me to sell well to their customers. And, so, I didn’t have much of an opportunity there. But I went on and started my own business, so I designed dolls and cards and sold them all over. As a matter of fact my business was one of three that started African American oriented greeting cards and stationary. There was one man in Detroit and a Jewish man in California that was going full color cards and my business. And that was all Woodford 12 in the country at the time. And so I designed the dolls that I mentioned, the little dolls and have you been to the library to see the exhibit that Tristan Reid did? HM: No, I haven’t. AW: If you get a chance to go to the library downtown, on the, it’s not the second floor but it’s the level like… it’s not really a mezzanine either. But when you go in and you go to the left and you step up a few steps and you go there, and you pass by the desk and my little rag dolls are in there. HM: I saw pictures on your website. AW: Ok. Ok. So, but the dolls… I created them in the early ‘70s when I started the business. I designed… I actually made one. But I just use the design of them for stationary. And I remember this one time when I had an appointment with the Army Air Force Exchange Service to sell products to them and I was told to meet them in Indiana. I was in Columbus. I drove all the way down to Indiana, there was nobody there to see me. That was really hurtful. I came back and I talked to this man that was in politics in Columbus and he said you need to call John Glenn. And I said, “Oh yeah?” And he was our senator in Ohio, so I called, and I think it was him on the phone and he said that won’t happen. So, within two weeks I had an order for my products to ship all over the country. HM: That’s amazing. AW: It is! That’s why I believe, you know, sometimes they do dramatic things. You remember when he in Hidden Figures how he went over to speak to those ladies that would have been ignored otherwise. I believe it. I believe he did that. It wasn’t just for dramatic effect. HM: That he was that kind of person. AW: That’s right. HM: So what kind of inspired you to make the dolls and the cards? AW: Just knowing that it wasn’t there and so for you if you find that there’s a need and there’s nobody filling it. Jump in there. If you know you can do it. And I knew I was an artist and I saw that there was nobody doing it around. When I worked in that department store black people would kind of slide over to me and they’d say, “How come there aren’t any black cards in here?” And so, I took their need to the people who bought cards and all. American Greetings and Hallmark were the main ones. And when I talked to the representatives from those they said, “Oh, you know, there’s no need for that. You know… Black people don’t care. They buy the cards that are here.” Well they didn’t have a choice. They had to. So finally, I got on them enough that they said why don’t you write to Hallmark because I had actually applied to work for Hallmark cards when I graduated from college and they said yes, but guess what? They said I could work for them, but I had to not graduate. I’d have my degree, but I couldn’t be there for graduation. I told them that I would need to be there till June the 6th when my graduation took place and they said well you have to be here on May the 30th or else you don’t get the job. So that was the end of that. Yeah So this is the kind of thing that you go through, that I’ve been through and a lot of people go through that and it may happen to you. It’s not saying that it couldn’t happen to you because your skin is white and mine is brown, but it was just a cold-blooded thing to say you have to be here in time… Actually, it wasn’t Hallmark. I apologize. It wasn’t them. It was Jack Lenoir Larson the fabric designers. That’s who hired me, and it said I was hired, come, they got my application and everything Woodford 13 and they agreed but I could not stay for graduation. And they knew what they were doing. They knew that I was not going to not graduate. So. It’s the way it is. But in order to fulfill the needs of people I started to design cards. Hallmark said send them some designs. I sent my designs and they said we’ll pay you six dollars for each design and that’s the end of it. So, I couldn’t get any commission on the designs or anything after that. Six dollars for each design so I said no. I might as well start my own business. So that’s what inspired me. (laughter) Yeah… HM: So, you said you left North Carolina and moved to California because there were more opportunities there right? AW: Well what happened was, I didn’t have any idea what the opportunities would be there except that the fact that I… I mentioned to you that I was the first black person to work in an office in Cherokee County. I was the first black teacher, although it wasn’t a full-time teaching position but I taught art in all the schools in the area except Murphy. And my friend Betsy Henn Bailey taught in Murphy. So, I was the first black teacher in the system and that was… that paid me some, but I did wallpapering. I did exterior and interior painting. Wall painting you know. Doing decorative kind of work and it still averaged out to $600 a month and I couldn’t pay my bills. I couldn’t buy a nice car or anything like that. I already had a car, but I couldn’t keep it up and do all the things I needed to do. So, when my sister and her husband called me and said there was a job out there, I threw down everything and went out to California. Got out there and the job, they decided they didn’t want to hire me for that job, but they did give me a job. It wasn’t doing what I was supposed to be doing but I did get a job. And I designed a program for that company that allowed them to… their sales to just skyrocket and they decided to then to lay me off. All of us. Not just me. All the sales people were laid off because my program was so good it brought all this money in and they were happy about that, so they laid… laid me off. So my brother in law and another man from the company decided to start their own company. But before…the reason it stunned me that those people laid me off was that I sold a million, six hundred thousand dollars’ worth of goods for them that year and they only had to pay me $24,000 for all of that and they still let… decided to lay me off. So, my brother in law and his friend decided they’d start a business. So their first year in business I went to work for them and sold eight hundred fifty thousand dollars’ worth of goods. So, I was a good sales person. But, when I started my own business and the state of California went through some kind of problem and they were giving me some trouble. My mother was sick in Andrews and I decided I need to come back home. I came home and I thought that in those nine years things would have changed where when I first tried to get work and they wouldn’t hire me that now they would hire me. But when I came home the hospital, the banks, nobody wanted me to… they’d say. “Oh, you’re over qualified. I’m sorry. You know… You can’t work here.” And I’m like, “but I want to stay with my mom and dad and help take care of them the rest of their lives. I’m gonna stay here.” Because when they say overqualified their sort of saying you will move out. You know you’ll stay here for a little while and then you’ll move on. So, I had to start, I actually went to Western for the 18 hours. My mom died and I, and… It was a really hard time because she had cancer. And so I was going through all that. It was very rough. But the woman at the bank who is a lovely, lovely lady. She called me up and she said “Ann, why don’t you go over there and apply for the chamber of commerce job” And I was like she must have been kidding.., a black chamber of commerce director. “Cause it was unheard of and she said, “What’s wrong with you? You’re as good as anybody else. Go on over there.” And I did and they hired me right on the spot. So, I was the chamber director in Andrews, and we had a great chamber and then some people came along from Florida or Atlanta or some place and oh our friends can do that job Ann’s doing for volunteer. Well that Woodford 14 didn’t last long but they let me go. So then same friend from the bank called me and said they’ve got a Cherokee County planner job open. No. laughing at her, again right? So, I went to Cherokee County planning and I worked there until somebody did the same thing again. In the meantime, I began to talk to these women that I was talking about and so I began to write grant applications and I said, we had five people working for One Dozen Who Care at one time. So, I did that then for many, many years. HM: So, um, what exactly does One Dozen Who Care do? AW: Well to put in a nut shell we train leaders and create community bonds. So, what we… training leaders meant that the board members would get training. We brought people in who would train them and teach them how to run a nonprofit organization. We were a 501(c)3. We are a 501(c)3. We have set up our board with bylaws and all that and we’re North Carolina nonprofit corporation and training leaders is that and creating community bonds is that all our products, everything we did… it was to tear down barriers between the races. We didn’t want… we wanted to present the programs for everybody. At the same time, we wanted to preserve African American history and heritage. So that’s what we’ve done over the years. And right now, it’s not at the same level that it once was. All of us are old and so we can’t find young people who are willing to commit like the older people did. So right now, it’s not doing the same thing and I don’t write grant applications. I hire people. But I’m thinking about doing it again. HM: Just going back full time to One Dozen Who Care? AW: No, I don’t want to do that. No. (laughter) No I need a break, I need to paint pictures. But to get a grant application to get someone young like you to go in and do it. But you have to have the money to pay that person to start. I can write grants. I’ve raised well, probably near two million dollars over those years for the organization. We did the All God’s Children project, follow up things for that, we do a multi-cultural women’s development conference every year. We had a program called Ten, Ten, Ten. Which was ten kids, ten projects, ten months and in that, each month they would learn something different. Like a lot of kids didn’t eat at the table, so we taught them how to set a table and to sit at a table and not be like I was. They can eat with a knife and fork. (laughter). So, we taught them and then for their reward for learning to do that we would take them out to a restaurant and let them sit in the restaurant… get dressed nicely. We took them down to Tuskegee University. We took them to Alex Haley Park. We took them to, um, the Betsy Smith Museum and to the MLK Center. Places like that where they could get a good feeling for who they are and that they are somebody and I thought it was a really good program and some of them wrote some letters that said it was really great after they got out of it. And actually, we had, the two… four best kids were these two little black kids and two little white kids. They were just excellent. The little boys were shy, but they did their projects. Whatever it was they did it. The little ones… they weren’t even ten years old. They were like our mascots. They did their projects like you wouldn’t believe and so the last one, little boy, the little white boy from Nantahala, his sister teaches at the learning center in Murphy and he’s a teacher now. He graduated from Western. HM: That’s awesome. AW: Yeah. That is awesome. Makes you feel so good and there… for somebody to be proud of. Now their little brother wasn’t in our Ten, Ten, Ten program but he turns out to be a head taller than both of them and when they see me, they just come and their so outgoing and loving and everything. I just loved that we tore those barriers down because they could have never been involved with any African Woodford 15 Americans. I don’t know what the relationship was like between them and the other kids, but I know that they are very loving to me. HM: That’s amazing. AW: So, it was a good program. Train leaders and create community bonds. What we have now is there is an African American book collection in the library in Andrews named after my father. That some board members decided that’s what we should do. Name it after Daddy. Then we still do the women’s conference and then we do something called an elder dinner where we honor some older black person who’s really worked hard in the community, but has never been noticed for it. So, we honor them, and we have honored white people who’ve done the same thing too, but mainly it zeroes in on something that they never get credit for. Yeah… HM: So, going to your All of God’s Children, right? What kind of inspired you to pursue that project? AW: What inspired me was my dad. My dad could tell all these stories. When Mama died, I took Daddy every Sunday for a ride because he loved to go show me where he’d worked and what he’d done and everything. And I go, “Here he goes again.” (laughter) He’s telling me the same old story over and over and one day… I could have had a V-8. What’s wrong with me? Daddy knows his history, but nobody… people would die, and you’d say, “Boy I wish I knew what they knew. Why did… they died, and nobody wrote it down.” You’d ask their family and, “Oh I don’t remember who that was.” So, they’d see a picture of somebody, and they looked at the picture that their mother had, and they go, “I don’t know who that was.” I’m like wow your mom knew her or she wouldn’t have had this picture up on the piano for all this time. So, I decided that I had to do it. And so in the evening, because my dad didn’t care for TV and he would make recordings on cassette tapes and things like that. But he was at home alone and I was at home alone and I would call him in the evening and just interview him and started writing all these things down. And then because where he was… like he’s just talking, he said in 1912 when they did the ethnic cleansing… he didn’t use that word ethnic cleansing, but when they did that in Forsyth County he said you know that was the year that the Titanic went down and you just kept going and I was like… “What?” (laughter) So I had to look it up you know. So, it was that kind of thing that inspired me. Then I thought about my grandfather and my grandmother and all that they had been through and I started to look up their names in Ancestry.com and started reading about my family and I’d go back to Daddy and say Daddy did such… and do you remember… “Yeah.” He’d start to tell me the stories. So that inspiration caused me to know that the people are invisible. If you drive down through Andrews and Murphy, you rarely see a black face. They’re at home or they’re at work and you don’t see like in the cities where you see blacks standing on the corners and everything. You don’t see that and so I thought that the invisible people need to be made visible and the way to do it is to write a book. So, it took me five years to write the book. Two years to get it produced and now since ‘15 I’ve been going out doing presentations on it. It’s time for me to slow down and do my artwork before I forget how. (laughter) Yeah, yeah…. HM: Right. I know I used… last year I used your book when I was researching for Ms. Bryson and used your book a lot for her. AW: Fantastic! Oh that’s great. HM: It’s an amazing piece of work. Woodford 16 AW: Oh, thank you. HM: I’m so glad you preserved that history because no one… AW: Thank you! They wouldn’t know. And that’s the whole thing. And that’s why I’m glad I did it even though I’m sorry that, you know… seven or eight years of my life I haven’t painted. I hardly paint at all and people say you need to paint. You know… you need your works out here for sale and I do need to so I’m gonna try and get back into that this year. Thank you for using the book. See that’s what I wanted. I wanted people to be able to use that book to research and I thank you for telling me that you used it. HM: I did. I read a lot of it before this too and was like wow. (laughter) Like… We just have never heard of that. It’s amazing. AW: Well that’s what happened when I went to Young Harris College. The older people that were over there were saying we didn’t know about Sundown towns or we didn’t know about whatever it was I was talking about. We didn’t know… somebody… I lived in Forsyth County for a while and had no idea that that had happened. But they just took everything that our families worked for and no compensation in what… in anyway. Just took it. Yeah. So, they moved to Bryson City, to Asheville. Some to up north to like Cincinnati and places like that. They had to go because they had no place. But just think of how that works that you try to build yourself up. And you know how they talk about taking two steps forward and one step back. Well that’s the way it’s been for many African American people and I, it breaks my heart when I see how they are in Chicago and cities like that, how bad the murder rate is and all that because they don’t even know their history. If they knew and could understand they wouldn’t do that. To each other or to anybody else. But it’s a sad thing and I would be afraid myself to go there and walk down the streets in a place like that because bullets, stray bullets are just flying. They don’t care about their lives because they don’t understand their history. So that’s why I suggest that you find out all about your family history and love it. You should love your history because, and even if they were slave owners, which the average white person’s family didn’t own slaves, okay. But the ones that did I say to them, “You’re not the one that did that so don’t accept that and make yourself feel guilty and not make a difference in this world.” So just take good care of yourself. It sounds like you’re going to be a great history teacher. Yeah. So, is that what you want to do? Do you want to teach? Or… HM: I think so. I’m either going to teach or I would love to work in a museum. I think that would be amazing. AW: Yeah. Pam Meister is a good one. I’m telling you now. You know you can work with her and Peter Koch, he’s wonderful. And I could see it with Tristan Reid’s work what he’s doing because he’s worked with them. They’re really good teachers. HM: Yeah. And I think Western… we’re so lucky to have that here in this community. AW: Andy Denson’s class, I spoke to them and Andy was really good. And Libby is really good. So, they’ve got a great group of people who care about the crossover of all the history of our people in the region. Yeah. HM: Which is good because I do feel like, this region especially since it’s so rural we don’t really have a lot of like history about it taught and so it’s nice that their kind of supplementing that in this area. Woodford 17 AW: That’s right. Absolutely. Great. So, I thank you for this. This has been a great opportunity to speak with you. Thank you. Do you have any more questions for me? HM: Unless there’s anything else you’d like to add. AW: Nothing more than just the fact that I am doing presentations so if you happen to talk with somebody that would like to have… church members, church groups or ladies’ groups. Whoever it happens to be. As a matter of fact, the man said he has the Sons of the Confederacy he wants me to come speak and I was like, “Yeah. I’d be glad to.” (laughter) So anybody that you hear of that would be interested in finding out more about African American history in this region tell them about me. HM: I will. AW: Thank you. HM: Thank you. AW: I appreciate it. HM: OK. So, I think we’re done.

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Ann Woodford is interviewed by a Smoky Mountain High School student as a part of Mountain People, Mountain Lives: A Student Led Oral History Project. Born in 1947 in Cherokee County, Woodford attended a one room school house for African Americans until the 8th grade after which her only option was a boarding school in Asheville, Allen High School. She discusses her many accomplishments, including starting a business creating African American greeting cards, being the first black person to work in an office in Cherokee County, establishing One Dozen Who Care, and her book When All God’s Children Get Together.

-