Western Carolina University (20)

View all

- Canton Champion Fibre Company (2308)

- Cherokee Traditions (293)

- Civil War in Southern Appalachia (165)

- Craft Revival (1942)

- Great Smoky Mountains - A Park for America (2683)

- Highlights from Western Carolina University (430)

- Horace Kephart (941)

- Journeys Through Jackson (154)

- LGBTQIA+ Archive of Jackson County (7)

- Oral Histories of Western North Carolina (314)

- Picturing Appalachia (6592)

- Stories of Mountain Folk (413)

- Travel Western North Carolina (160)

- Western Carolina University Fine Art Museum Vitreograph Collection (129)

- Western Carolina University Herbarium (92)

- Western Carolina University: Making Memories (708)

- Western Carolina University Publications (2283)

- Western Carolina University Restricted Electronic Theses and Dissertations (146)

- Western North Carolina Regional Maps (71)

- World War II in Southern Appalachia (131)

University of North Carolina Asheville (6)

View all

- 1700s (1)

- 1860s (1)

- 1890s (1)

- 1900s (2)

- 1920s (2)

- 1930s (5)

- 1940s (12)

- 1950s (19)

- 1960s (35)

- 1970s (31)

- 1980s (16)

- 1990s (10)

- 2000s (20)

- 2010s (24)

- 2020s (4)

- 1600s (0)

- 1800s (0)

- 1810s (0)

- 1820s (0)

- 1830s (0)

- 1840s (0)

- 1850s (0)

- 1870s (0)

- 1880s (0)

- 1910s (0)

- Appalachian Region, Southern (15)

- Asheville (N.C.) (11)

- Avery County (N.C.) (1)

- Buncombe County (N.C.) (55)

- Cherokee County (N.C.) (17)

- Clay County (N.C.) (2)

- Graham County (N.C.) (15)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Haywood County (N.C.) (40)

- Henderson County (N.C.) (5)

- Jackson County (N.C.) (131)

- Knox County (Tenn.) (1)

- Macon County (N.C.) (17)

- Madison County (N.C.) (4)

- McDowell County (N.C.) (1)

- Mitchell County (N.C.) (5)

- Polk County (N.C.) (3)

- Qualla Boundary (6)

- Rutherford County (N.C.) (1)

- Swain County (N.C.) (30)

- Watauga County (N.C.) (2)

- Waynesville (N.C.) (1)

- Yancey County (N.C.) (3)

- Blount County (Tenn.) (0)

- Knoxville (Tenn.) (0)

- Lake Santeetlah (N.C.) (0)

- Transylvania County (N.C.) (0)

- Interviews (314)

- Manuscripts (documents) (3)

- Personal Narratives (7)

- Photographs (4)

- Sound Recordings (308)

- Transcripts (216)

- Aerial Photographs (0)

- Aerial Views (0)

- Albums (books) (0)

- Articles (0)

- Artifacts (object Genre) (0)

- Biography (general Genre) (0)

- Cards (information Artifacts) (0)

- Clippings (information Artifacts) (0)

- Crafts (art Genres) (0)

- Depictions (visual Works) (0)

- Design Drawings (0)

- Drawings (visual Works) (0)

- Envelopes (0)

- Facsimiles (reproductions) (0)

- Fiction (general Genre) (0)

- Financial Records (0)

- Fliers (printed Matter) (0)

- Glass Plate Negatives (0)

- Guidebooks (0)

- Internegatives (0)

- Land Surveys (0)

- Letters (correspondence) (0)

- Maps (documents) (0)

- Memorandums (0)

- Minutes (administrative Records) (0)

- Negatives (photographs) (0)

- Newsletters (0)

- Newspapers (0)

- Occupation Currency (0)

- Paintings (visual Works) (0)

- Pen And Ink Drawings (0)

- Periodicals (0)

- Poetry (0)

- Portraits (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Programs (documents) (0)

- Publications (documents) (0)

- Questionnaires (0)

- Scrapbooks (0)

- Sheet Music (0)

- Slides (photographs) (0)

- Specimens (0)

- Speeches (documents) (0)

- Text Messages (0)

- Tintypes (photographs) (0)

- Video Recordings (physical Artifacts) (0)

- Vitreographs (0)

- WCU Mountain Heritage Center Oral Histories (25)

- WCU Oral History Collection - Mountain People, Mountain Lives (71)

- Western North Carolina Tomorrow Black Oral History Project (69)

- A.L. Ensley Collection (0)

- Appalachian Industrial School Records (0)

- Appalachian National Park Association Records (0)

- Axley-Meroney Collection (0)

- Bayard Wootten Photograph Collection (0)

- Bethel Rural Community Organization Collection (0)

- Blumer Collection (0)

- C.W. Slagle Collection (0)

- Canton Area Historical Museum (0)

- Carlos C. Campbell Collection (0)

- Cataloochee History Project (0)

- Cherokee Studies Collection (0)

- Daisy Dame Photograph Album (0)

- Daniel Boone VI Collection (0)

- Doris Ulmann Photograph Collection (0)

- Elizabeth H. Lasley Collection (0)

- Elizabeth Woolworth Szold Fleharty Collection (0)

- Frank Fry Collection (0)

- George Masa Collection (0)

- Gideon Laney Collection (0)

- Hazel Scarborough Collection (0)

- Hiram C. Wilburn Papers (0)

- Historic Photographs Collection (0)

- Horace Kephart Collection (0)

- Humbard Collection (0)

- Hunter and Weaver Families Collection (0)

- I. D. Blumenthal Collection (0)

- Isadora Williams Collection (0)

- Jesse Bryson Stalcup Collection (0)

- Jim Thompson Collection (0)

- John B. Battle Collection (0)

- John C. Campbell Folk School Records (0)

- John Parris Collection (0)

- Judaculla Rock project (0)

- Kelly Bennett Collection (0)

- Love Family Papers (0)

- Major Wiley Parris Civil War Letters (0)

- Map Collection (0)

- McFee-Misemer Civil War Letters (0)

- Mountain Heritage Center Collection (0)

- Norburn - Robertson - Thomson Families Collection (0)

- Pauline Hood Collection (0)

- Pre-Guild Collection (0)

- Qualla Arts and Crafts Mutual Collection (0)

- R.A. Romanes Collection (0)

- Rosser H. Taylor Collection (0)

- Samuel Robert Owens Collection (0)

- Sara Madison Collection (0)

- Sherrill Studio Photo Collection (0)

- Smoky Mountains Hiking Club Collection (0)

- Stories of Mountain Folk - Radio Programs (0)

- The Reporter, Western Carolina University (0)

- Venoy and Elizabeth Reed Collection (0)

- WCU Gender and Sexuality Oral History Project (0)

- WCU Students Newspapers Collection (0)

- William Williams Stringfield Collection (0)

- Zebulon Weaver Collection (0)

- African Americans (97)

- Artisans (5)

- Cherokee pottery (1)

- Cherokee women (1)

- College student newspapers and periodicals (4)

- Education (3)

- Floods (13)

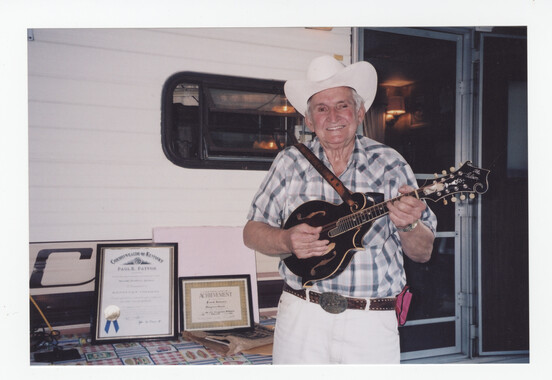

- Folk music (3)

- Great Smoky Mountains National Park (N.C. and Tenn.) (1)

- Hunting (1)

- Mines and mineral resources (2)

- Rural electrification -- North Carolina, Western (2)

- School integration -- Southern States (2)

- Segregation -- North Carolina, Western (5)

- Slavery (5)

- Sports (2)

- Storytelling (3)

- World War, 1939-1945 (3)

- Appalachian Trail (0)

- Cherokee art (0)

- Cherokee artists -- North Carolina (0)

- Cherokee language (0)

- Church buildings (0)

- Civilian Conservation Corps (U.S.) (0)

- Dams (0)

- Dance (0)

- Forced removal, 1813-1903 (0)

- Forest conservation (0)

- Forests and forestry (0)

- Gender nonconformity (0)

- Landscape photography (0)

- Logging (0)

- Maps (0)

- North Carolina -- Maps (0)

- Paper industry (0)

- Postcards (0)

- Pottery (0)

- Railroad trains (0)

- Waterfalls -- Great Smoky Mountains (N.C. and Tenn.) (0)

- Weaving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Wood-carving -- Appalachian Region, Southern (0)

- Sound (308)

- StillImage (4)

- Text (219)

- MovingImage (0)

Interview with Ann Woodford

Item

Item’s are ‘child’ level descriptions to ‘parent’ objects, (e.g. one page of a whole book).

-

-

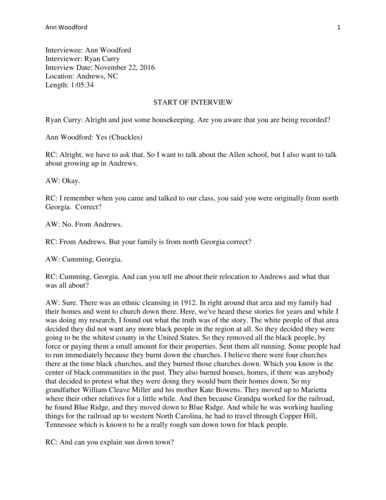

Ann Woodford 1 Interviewee: Ann Woodford Interviewer: Ryan Curry Interview Date: November 22, 2016 Location: Andrews, NC Length: 1:05:34 START OF INTERVIEW Ryan Curry: Alright and just some housekeeping. Are you aware that you are being recorded? Ann Woodford: Yes (Chuckles) RC: Alright, we have to ask that. So I want to talk about the Allen school, but I also want to talk about growing up in Andrews. AW: Okay. RC: I remember when you came and talked to our class, you said you were originally from north Georgia. Correct? AW: No. From Andrews. RC: From Andrews. But your family is from north Georgia correct? AW: Cumming, Georgia. RC: Cumming, Georgia. And can you tell me about their relocation to Andrews and what that was all about? AW: Sure. There was an ethnic cleansing in 1912. In right around that area and my family had their homes and went to church down there. Here, we've heard these stories for years and while I was doing my research, I found out what the truth was of the story. The white people of that area decided they did not want any more black people in the region at all. So they decided they were going to be the whitest county in the United States. So they removed all the black people, by force or paying them a small amount for their properties. Sent them all running. Some people had to run immediately because they burnt down the churches. I believe there were four churches there at the time black churches, and they burned those churches down. Which you know is the center of black communities in the past. They also burned houses, homes, if there was anybody that decided to protest what they were doing they would burn their homes down. So my grandfather William Cleave Miller and his mother Kate Bowens. They moved up to Marietta where their other relatives for a little while. And then because Grandpa worked for the railroad, he found Blue Ridge, and they moved down to Blue Ridge. And while he was working hauling things for the railroad up to western North Carolina, he had to travel through Copper Hill, Tennessee which is known to be a really rough sun down town for black people. RC: And can you explain sun down town? Ann Woodford 2 AW: A sun down town is one that would make it very well known that if you were black, you better not be caught there after sun down because the law would not protect you. RC: Right. AW: We were surrounded by sun down towns in Andrews in this area, Cherokee county and this region, is surrounded by former sun down towns. But Grandpa had to come through so he said that he would have to do most of his hauling on moonlit nights. He would travel not on the highways, he would travel through the woods with his horses and his wagon. And I wrote a little preface to tell you a story of how he was so afraid even later in the 1970s. How fearful he was of being in that region. So he came up to this area and he found the people in western North Carolina, Murphy, Andrews, Cherokee county this area to be completely different. They were friendly, they were willing to sell property to him. So, he came up and bought the first property and built the first house in Happy Top, which is the traditional black community here. Along with one other one which was called Snake Town and they were right close together. So that's how we got here because Grandpa went from here to Swain County and met grandma who was a Howl. Married her and brought her back here and they had eight kids. And they were sharecroppers mostly. My dad learned farming from his dad, and Daddy just broke out and decided, his name was Purell Miller, he was Grandma's favorite son, she always. It's hard to say that, right? But they are all passed and gone now. But he was the favorite because he would do anything for his mother, and his dad also. But they were sharecroppers but Daddy learned how or do roofing, and building, and contracting of all kinds of jobs, painting houses, you name it he did concrete work, and everything. But he is most well, known for his butchering hogs. Most of the young people even around here know some stories that their grandparents had told them about my dad coming to kill their hogs way down in the lower end of the county as we called it. Or even into the sun town areas of Hiwassee, he went to Robbinsville, which was a sun down area in Graham county. He went over there and he was always well received. And he introduced me to people from over there. And I've always had a good relationship with people from Graham county. And it's really good to know that there are good people you might have fifty miles or one hundred miles from here some people that really just did our people in a really bad way. But then you turn around twenty-five or fifty miles that are just golden when it comes to love and care. So it means a lot to me to work to bring down the barriers between the races. RC: Right. I read a book earlier this semester. It was called Remembering Jim Crow. I don't know if you've heard of it AW: I've heard of it, but I haven't read it. RC: It's chilling. It's a very interesting book. It basically… Its oral histories. It talks about doing just what the title does, remembering Jim Crow. There is multiple different sections, but the first one it talks about is coming to understand being oppressed. Do you have any stories like where you just like… understanding the social circumstances of living under Jim Crow. Do you have anything that can illustrate that? Like wow this is Ann Woodford 3 AW: The main thing for me is, and I didn't know it then, was being a child in a one room one teacher all black school that had a coal stove and an outhouse for our bathroom. That you would go there, my dad would build a fire, and if some of the kids who didn't like going to school could get there in time they might smother the fire out. So we would hopefully get to go home, but we would not get to go home our teachers wouldn’t let us. That would be the worst thing. I am one of the privileged people, meaning that in this community, my dad was well known. His father was well known. We always have been a small number of African Americans, of course. We are one point six percent in the whole western region. When there are smaller groups of African Americans anywhere, usually there is not as much racial tensions. And so, I don't have a lot bad stories that I could tell that way. I've never been called the n word in my life that I ever know of. They might have called it behind my back, but I never was called it to my face. There was, my dad was a very protective person to the family, and it didn't matter to him what color the person was, if they messed with his family, he was going after them. He turned out to be an extremely peaceful man in his older years, but when he was younger he was tough. I can recall when the little girls were killed in Alabama, the four little girls where the churched was bombed, the little girls died. Some white kids thought they could have fun with us and scare us. They were young people. They came up to our community. Now Texana is the black community in Murphy. So if you go through Texana you can drive straight through Texana Road go back out to Joe Brown highway. It's open. You can zoom through there and do anything you want to and get away. In our little community, they had no idea that in Happy Top is was a dead, end road, they came up and threw fire crackers in our yard. And it sounded like shots. My dad was sleeping in the chair. I remember my little heart was beating so fast and everything. My dad kept three guns in the corner right behind his chair all the time. And it wasn't set there for a specific thing he just wanted to have his guns handy when he wanted them. And in those days you didn't have to worry about breaking into your house as much and stealing your guns. So Daddy was in one fail swoop up. His feet were in his boots, his hand was on his double, barreled shotgun. And his shells were there, he grabbed shells put them in his pocket, he’s loading his… Momma is on his arm saying "Purell please don't go out there, don't go out there!" He’s dragging her. He was a really powerful man, he was dragging her out the door and she is begging and pleading and he said "Take care of the kids!” He goes up the road, the car found out, they found out when they got to the end of the road they couldn't get through, in no way could they get through in the car. So when Daddy is going up the road. And I think about it now, Daddy was blessed, he was truly blessed because there were so many times he could have killed. They could have come down the road and run him over with the car, or whatever. But he's going up with his shot gun loading it as he's going, and they see him coming. And when he got to the car the lights were on bright, the doors were all open, and they were nowhere to be seen. So they ran on foot through those woods to get out of there. To this day I don't know who they were. Daddy never even told us who they were. But he came downtown, he identified with the tag whose car it was, and he came downtown and told the police. He had the gun with him at the time. And many years later, it was a funny story to me, I was downtown with my dad, I was a grown woman then, and the police chief was out there on the street. And he greeted Daddy, and they greeted each other and they always had some old stories to tell and everything. The police chief said "Ann, your daddy was really something else when you were young." He said "he came downtown with a gun one day, and I took that gun away from him," Daddy said "Yeah sure you took my gun." He just fell out laughing because he knew he didn't take my dad's gun. It shows how people don't have to be evil Ann Woodford 4 and racist in the way the people were in Cumming, Georgia, in that area, Forsyth County was a horrible place with the white caps and other groups were like KKK. RC: Right. I believe they were on the cover of Time magazine in Forsyth County in the eighties because… it might have been earlier before that, but there was a march that was an African American march AW: Yes. RC: Because they were challenging because it's not far from Atlanta. South Forsyth is only twenty minutes from Atlanta. It was just de facto, they were, I know the Klan was very active in that area is a little bit I think. AW: Well it sure is. It's all over the country. They just nicknamed themselves Alt Right now, it doesn't really matter they're still there. Not to say that's the majority of the people at all, I don't believe it is. But there are people who still say that this country was made for white people, in all of their progeny. It was in the news here recently, it might have been this past week, that the head of the Alt Right group, and I can’t remember if they have a special name, stated that. So this is really… racism is not understood by me. Because when people said we don't want black people to drink out of the same faucet. Well it might have been because they looked at the people and they didn't have many teeth in their mouth or their breath smelled because they didn't have toothpaste and toothbrushes and things like that. And maybe they thought that was the reason. But what was the reason people were in the condition? That's the question that you have to ask. Why were they in that condition? Because wages? My dad was working on the job once. He was the supervisor because he knew how to do the work. And the other people were just all white people, and they were working on the job too. They didn't really know, they didn't have the skills he had. So they hired him as the supervisor. And they were from up north someplace, the people who had hired all these folks, so they came and saw supervisor on there and handed the check to Daddy. Daddy looked at the check and was like "whoa this is great" then he looked and saw his name wasn't on it. They were paying white people who didn't have his skills as supervisor pay salary, and he was getting paid minimum compared to that. That stuff still goes on. I'm about to make a speech in my communications class over in Tri, County, and I need to be able to talk about this in a way people understand. You're a college man who is trying to learn more about the whole situation, the whole story. That talk what you saw about the march, I know the man's name but it won't come to my mind but I do remember Oprah Winfrey went back down with them and it made a difference. And not only that, but I think what she did made a difference. Because Oprah is one of those people that is more open to everybody. So she had this forum, and white people were standing up that were from Forsyth County, on television, stating that they didn't believe in this racism. They lived there, but they didn’t believe in it. So I am very pleased that there are people like Oprah and other people, even John Lewis, as much as what’s happened to him. He's not racist in that way. And he’s won his position because white and black people voted for him. Not just black. RC: Can you tell me about your educational experience before Allen School? Ann Woodford 5 AW: I went to, up here in Happy Top, was a one room one teacher all black school. When I first went there, the kids, there were probably about maybe eight kids that had to leave that next year because the tannery had closed here. The tannery is where most of the black men, black families worked. When the tannery and the extract closed down, white and black people had to leave Andrews area. Because extract didn't hire black people, but the tannery did. The parents left to go north, left their kids with their relatives, or one family even left their kids with just their teenage siblings to take care of them. They left here. The school had probably twenty some kids when I first went in my first grade. The teachers have all come from outside of Andrews, of course we didn't have any… RC: White teachers or…? AW: No. Black, always black. It was an all, black school. Our teacher the first year was from Sylva. And she had two boys, and she had them in school here because she had to have them with her. But the saddest thing about it was that there was no place for a black teacher to live except in a black home, and the people in our community were poor. So they might have to take their kids out of their bedroom, and move them onto the back porch or into the living room on pads on the floor, to be able to give the teacher a room. So this teacher would have to have her two boys and herself sleeping in one room in a house. The house had an outhouse, a well, they didn't have running water. All these teachers that came should be so honored. That's why I wanted to mention them. And I didn't get all of their names because people couldn't remember who they were and that's why I had to write book. Because I didn't want those people to be forgotten. People who sacrificed their lives, a better life for themselves, to come to Andrews to come teach these little kids. And to come to Murphy. So the teachers lived in the peoples’ homes. They were there on times always. I never remember going to school when the teacher wasn't already there waiting for us. We had to walk to school, but it wasn't that far. My school walk would probably be no longer than two Andrews blocks from here. It was very important for us to learn. And the good thing about being in a segregated school was that we learned that we were somebody. We were okay. Our people had done wonderful things in this world, and that was so important because, white schools, and that's all we can still call them, white schools, only taught white history. Never taught us, for years there was nobody black in a history book except Dr. Martin Luther King. And that is so unfair because what it has done is caused blacks to be in some of the positions that they are in today. That you see bitterness, you see hatred of each other because of IRO Internal Racial Oppression, they look at each other, they don't see any worth in each other. They don't see black people as worthy. You might see Michael Jordan, the sports stars are big names, and Oprah Winfrey’s a big name, but they know they are not going to be in that category. I'm never going to be Oprah Winfrey. And I know that but that doesn't stop me from knowing that I'm still worthy, I'm still a worthwhile person. That I can reach out and do something to help anybody. Does not matter what color they are, what race they come from, and even religion, because I just think that the racism that has gone on in this country has been black against other races. Some of it has been perpetuated by the system that is run by white people. I have no question about that, but black people have minds, they don't have to be prejudice. So I always tell them. That if one talks to me with prejudice about Latinos, or Jews, they say these things, I'm always going to say no, but look where you are. How do you think other people feel about you? I think this school system that you ask about was very rotten against us to tell the Ann Woodford 6 truth. The first school principal was Mr. Ruffdey and there are people around here who still remember Mr. Ruffdey. RC: And he was…? AW: He was the school superintendent. I'm sorry. Actually Andrews had its own school system it wasn't Cherokee County schools at that time. So I guess he was the principal/superintendent. I know that he was the head of the schools. He would come to our school maybe quarterly, maybe twice a year. He would have his hands in his pockets, almost like if I touch one of these little things I'm going to get some of this off on me. And we knew that. We had our minds. We were little kids but we understood he didn't want to be there. Mr. Frazier, the man Charles Frazier that wrote the book, I can't think of the name of the book. They made a movie of it. I know that book, I just can’t think of it right off. [Cold Mountain] But his father was a better one. He was better to us when he came. Not that he was friendly and came over and put his hand on us and talk to us nicely, but you didn't feel like he felt he was going to get dirty being there. This shows you how my memory of it, the difference because I was older and I could still remember how Mr. Ruffdey treated us when he came. When we wanted supplies, we had to walk from here, up to the hill up here where the white school was. We had to walk to get our supplies. Nobody bothered to bring supplies over to our school for us. When I was older, probably 7th and 8th grade, they allowed me to be one of the ones to go over to the white school to get some supplies. Our books were always used. They had names of white kids in it that we recognized, and it didn't make you feel good that you were never getting a new book. RC: Just hand me downs. AW: Just hand me downs. And that meant if there was a new math or a new English book, you weren't getting the newest one. You were getting the old stuff that had been around for four or five years handed down to you. There were people in the school system up here that saw… they could see it, but couldn't do anything about it, white people. Two white women that I recall that were up there were Judy Brooks who is now the bank manager at United Community bank, wonderful woman. Ms. Ardith Hay was exceptional, she was very nice she would bring us supplies and talk to you like you were a human being. She looked at me. A lot of people just put the stuff down and they would even look at me like I was nobody. But she did. That school system was rotten in a lot of ways, but the best thing about it was those black teachers told us we were somebody and that we could make. And I was the valedictorian of my graduating class from 8th grade class. I told you that? RC: No. AW: Because I was the only kid in my grade from 2nd to 8th grade. RC: That was one of the focuses of Remembering Jim Crow. Of how important African American communities are and how the institutions, schools, churches, all just helped deal with the realities of living under Jim Crow. The importance of that school kind of showed it. The teachers especially. Teaching you that you could teach somebody, that was similar to what that book had in it. So Allen, you went there in 9th? Ann Woodford 7 AW: I went straight there from 8th to 9th. From 9th to 12th grade at Allen high school. RC: Okay. And did you board there? AW: Yes. In Asheville. RC: So did you feel insulated in Asheville? AW: Oh were we insulated in Asheville. I didn't know anything about what was really happening out here with sit, ins and the civil rights movement was sort of kept from us. RC: And what years was this? AW: I went from 1961 to 1965. RC: That's right in the heart of all of it. AW: There ae people, my first little boyfriend, his sister was one who was sitting in downtown from Stephens Lee, was sitting in the counters downtown. I didn't know that. RC: And that was in Asheville? AW: Yes. And there is a picture in the book. I was totally insulated. My folks insulated us pretty much as children. They always talked about the good times. We heard more about the good times. I was eight years old when Emmitt Till was killed, murdered down there in Mississippi and it just made a lot of difference in the way I looked at who I was as a black child. I didn't even know I was black. I didn't know I was poor. And most of the kids if you ask them that grew up up there, we didn't know we were poor. But going to Allen High School, if you took the whole staff and the whole, all the teachers as well as the other staff members, they were about half and half black and white. Most of the teachers were white and most of them were from north. The English teacher that we had was from Kentucky originally and she was so excellent. She was strict and we feared her but somehow we didn't hate her. We feared her because we didn't want to mess up. And most kids didn't want to go back home to nothing, because in Andrews that was the end. You could not go to high school after 8th grade. And you didn't have money to go to Murphy, they had it until 10th grade, and that was the end of their education. So if you didn't stay at Allen or Stephens Lee… RC: But meanwhile white schools are going all the way through 12th grade, but black high schools just 8th grade. AW: Exactly. Yes and that was intentional. Wanted us to stay here and do the labor and the domestic work and all that. That's what ended up happening most of the times until plants came along, and then black people started going to the plants to work. But they still didn't go on to get further education, many of them. Ann Woodford 8 RC: So your teachers at the Allen School, there weren't white students there? AW: There was one. RC: From up north right? What was her name? AW: I forgot her name off the top of my head. RC: But there were white teachers. How was, you mentioned in elementary school your black teachers were very important because they taught you that you were worthy. What about the white teachers? Was there any difference? Was there any racism amongst the white teachers? AW: I never felt any. And I can't remember any of the girls that I grew up with in school saying this was a racist place. They would say things that now if you said it today would make black kids upset. They would say now look girls you’re going to straighten up, you’re going to do this, you’re going to do that. You know you could not go out half, dressed, your hair had to be combed. You could not go out without a bath. If they smelt anything on you were sent back to the dorm to get clean. RC: Very strict. AW: Very strict. When you walked out you had to wear dresses, we couldn’t wear pants. When you walked down, I lived on the second floor and some lived on the lower floors, but I think I always lived on the upper floors. When you walked down, there was somebody on the stairwell that caught the ones on the first floor and second floor, to reach down and pull up the edge of your skirt to see if you had on a slip. That's how strict they were. They would say you have to be twice as good to go half as far as a white person in this world, so you need to study, you need to work, so they had, you go to school all day, then go to dinner and after dinner you had thirty minutes to play, to do whatever you wanted to do. Then you had to go to study hall from it was 6:30, about 6:30, if you got finished eating early you could go back to your room before that, but I think dinner was at 5:30 you had to 6:30 maybe to play around and get yourself ready to go to study hall. Then from study you had to stay from seven to nine. You had to stay there and you better not be caught sleeping. It was that strict. Then you went to your room and at 9:30 the lights were out. You didn't have a chance to do too many bad things. The last thing about that is that, and several of my friends, we were in a little group that we call a clique maybe, that we really wanted to make it big in school. We wanted to do well. So we would sneak up after the teacher went to her room, the hall supervisor went, and go to the bathroom to study. Because they would leave the lights on in the bathroom. So I remember a couple of times putting my feet up… Interruption AW: I remember the hall supervisor checking and I would put my feet against the door so she couldn’t see my feet under there. Others they would go in the tub and pull a curtain. We would have the bathrooms full just studying because we wanted to do well. RC: Like you were saying there was not a lot of time for… Ann Woodford 9 AW: Trouble. RC: Or, I mean news AW: We didn't have TV's. RC: So you didn't know much about what was going on. Do you think that insulation kind of helped you? You were forced to be… You didn't have time to do anything but work. AW: It did. RC: What would you do on weekends and stuff? Were you back home? AW: No. They only allowed you to go home on Thanksgiving and Easter for that period of time, the breaks. You could go one weekend in between the start of school and Thanksgiving in between the beginning of the next semester and Easter. You could go home then. But basically you could go out if there was somebody in the city that your parents gave permission, you could go out on the weekend. We went to church on Sunday. RC: What church? AW: All over Asheville. Whatever your religion was you could go to church. There were Catholics there who would have to get up in the morning and go to mass early and then go back to Baptist, or whatever churches were with us later. Because nobody was allowed to stay in the dorm while the rest of the people were at church There was a church across the street called Berry Temple and if it was bad weather we filled up that church. But we loved it. People in Asheville have joked and laughed about how they would come out on their porches to watch us go by because we had to dress really nicely, and we had to wear high heel shoes and hats and those kind of thing. They said it was like a parade every Sunday. They would come out on the porch to watch the Allen girls trick by to go to the different churches. RC: And in Asheville did you ever experience any racism on the weekends or anything like that while you were out or anything? AW: Nothing that I remember. We didn't really go out into Asheville on the weekends like that. In the later years of my time there you could go with somebody to chaperone you downtown. That could be sometimes in the evening right after school between school and dinner, or something like that quickly. You could go, they didn't give you much time you had to get there and do what you needed to do and come back. But Asheville I don't recall any incident that I could have been a part of. But I do know that we had African students there. We had some that had escaped from the Congo and we were kind of upset, it made us a little bit jealous that when the Africans went downtown the white people treated them better. RC: Really? Ann Woodford 10 AW: African Americans were mistreated meaning that they watched every move you made, that way that was for sure. They followed you around to see that you didn't steal anything. You had no thought of stealing, I mean I never had a thought of stealing something. But they would follow you around and they were not nice they would throw your change on the counter and never hand it to you in your hand. I remember those kinds of things. But when the Africans went downtown it was a different story. One of the Africans was a very, we called her uppity. She said she was a princess or something, you know how people tell those stories. Her sister… she came out in some legal way from the Congo at the time. Her sister, by the time her sister came who was younger, she had to crawl out to escape from where she lived. Her sister was completely different, everybody loved her because she was laughable. She laughed and the other one was always like this. They told a story about her going downtown to, she wanted a radio, and she was in the store and she says she wants the radio. And the lady said, "well that's twenty dollars" and she pretended that she couldn't speak English, she spoke perfect English, pretended she couldn't speak so she gives the lady a ten dollar bill. The lady says "well that's twenty dollars" and she goes "thank you thank you.” And the lady let her have it for ten dollars. If that would have been one of us, we would have been kicked out of there for sure. RC: So after Allen what did you do? AW: Allen was, they were insistent that all of us, I was in the largest class that ever graduated from there and there were fifty-five of us, and there were sixteen honor graduates. And because I was in that little group, the little group we were in, most of us were the honor students and I ended up graduating fourth. It was a very good upbeat thing for me to know that I came from Andrews, from a little one room one teacher school to be able to graduate fourth in this class. Every girl was, had been accepted into a college all fifty-five. A quick story, maybe it’s quick, I talk too much I know. My dad was working labor around here doing all this hard work and everything and of course, I was a teenager I had no idea how hard it was for him to make the money so I wanted to go to American University in DC. I was an artist, I was born an artist, I know that's my skill, my talent that was given by God. They told me you need to apply for some colleges so I applied for Ohio University because they had a really good art school and I applied for American University. Ohio University sent back immediately, and I probably applied for another in North Carolina at the time, but the first one that wrote back and accepted and said you had an out of state scholarship was Ohio University in Athens, Ohio. So I said, “Daddy I need sixty dollars,” or whatever it was for an application fee, so he gave it to me, didn't seem to be reluctant about it. But when my application from American University came and I said Daddy I need application, he was like, you got your application fee, that's it, no more. So I had to go in that way to Ohio University and Daddy took me up, my uncle drove us, and Daddy went with me to go up to see the campus and everything in the summer. And so I went to Ohio University. I really loved being that far away after a while. It's hard when you first go, like it was really tough when I left Andrews to go to Asheville. I cried for about maybe five days, probably not a whole week. Because I didn't want to leave home. RC: And it's outside of the south, how was that different? Like a cultural shock? AW: It was different, but what I found was that there was more of an acceptance by instructors and all. I mean I never saw any instructor act racist toward us. Some of the students, black Ann Woodford 11 students mainly, did things that really upset me. That was that here I was coming from the south where I had read, it wasn't as if l didn't read some newspapers and things, but to be a part of the civil rights movement wasn't in me because of where we were, and insulated as you say. But got up there after all these people being beaten and hosed and dogs even, all these things to get rights. Got up there and there was a table full of all blacks. And I wanted to know why in the world, why are all the blacks here, you mean to tell me they have segregation up here? Am I supposed to sit at that table? It was explained to me carefully, no that no that's their choice. They choose to be separated. RC: Sort of de facto segregation? AW: Yeah. And I had my hair straightened and quite a few of the girls had afros, and the guys all had afros. And one day I was sort of accosted verbally by one of the guys who said, Who are you? Do you think you are white? I was like, “What do you mean?” Because one of the first friends I made was a woman whose family was from Amsterdam. Heidi and I were really close. We went places together and I sat with her, not at the black table. So, it was different in that way. I told him no, it’s up to you if you think I am. That’s where I began to get some self-esteem, my own. Not being told at home what to do, and told at Allen what to do, but beginning to understand, you don’t have to sit at that table. There’s no way in the world they are going to force that. And a quick story, nothing is quick with me. You know that. But a story is that my roommate, it has to be two together, but three of us went from Allen High School to Ohio University, the valedictorian was one, but she decided to go there late. So the three of us would have been in the same room, but since she was late she lived across campus in another place. The other one and I were in our room, we got there first. When we got there a white girl walked in the room and we had already decided that whoever came, we didn’t know if it was going to be a black or white person, but that person was going to get the choice of the bed because there was a bunk bed and a single bed. So we were sitting in chairs waiting, talking to each other and saying that person, whoever it is will get the choice of the beds because we are pals you know from way back. And the white girl walks in the room and her face looked, I mean it was like shock. Well her mother was coming down the hall behind her and she was friendly, her face flushed after she blanched first and then her face turned red and she was like hey guys. You know. And everything. Her mother comes in and she goes, “Oh my god,” you know. She saw us sitting in there, and she said, “Oh mom, meet my roommates,” [laugh] and she was like, “I need to talk to you.” So they went out in the hall and we could hear this argument going on in the hall, and Terry came back in and she said, “My mom doesn’t want me to stay in the room with you, but I told her I’m staying.” And so we stayed together. So it was good. It was not the best thing, because Terry was wild. My other roommate and the two of them became really good friends. Things changed so well though. My roommate, the black roommate from Allen, went to breakfast one morning, I wasn’t planning to go to breakfast, it shows how my self-esteem grew. She went to breakfast and she came back crying and I said, “Why are you crying?” and she said the kids at the black table were talking about her so bad saying she thought she was white. And why do you think you’re so great and all this stupid stuff .and I said, “Well, why are you crying?” and I said, “You know you’re not white, you don’t care, you’re not trying to be white, so why you crying?” well, it just hurt my feelings so bad. I said, well, and I put my things down and I went over there. And I went to breakfast and they were like hello, and I was like hello. They must have read something in me right? So I went to breakfast, got my breakfast, went over Ann Woodford 12 to another table and ate and as I was coming back to the dorm, two black girls were following me. And I thought, they are going to try to beat my behind. [laugh]. And when we got to my dorm they said, “Hey, hey, we’d like to meet you.” And they invited me to become a part of their sorority. And I refused because two things, wisdom and the holy spirit said you better not join that sorority, they are going to beat your behind real good and legally do it because you know how they do that stuff in sororities. So I told them no, I never joined a sorority. And I’m glad to this day. [laugh] RC: so Fifty-five, all fifty-five in the Allen Home went to college. AW: I can't say that everyone went, but they all were accepted to college. RC: Accepted. And did most of them apply to schools outside of the south? AW: No, many went to in state schools. RC: Okay, I was curious about that because you said three went to Ohio. I was curious if that was kind of a trend to go up north. AW: I don't think so. I think, I really would say probably most of them went to southern schools. RC: Okay very interesting. Obviously, just application, that was a challenges with colleges, just the one application. AW: Money. Yeah. RC: Were there any other challenges applying to college like acceptance and stuff like that? Or were schools, were there any I guess… AW: I don't know to tell you the truth. I know that American University sent me application. I really don't know what others went through if any of them were turned down because they you know, but it was 1965 to 1969 when we were graduating from my class. Many of the barriers had already come down to white institutions taking in black students, so I never heard any of that. RC: And when you, going back to Allen, was Asheville like was that segregated like water fountains and stuff like that at that point in time? AW: Oh yes during that time. Oh yes. RC: And what about in Ohio, nothing, it was nothing like that? AW: I didn't see any of that. RC: So you said, I was going to ask about if you were involved in civil rights protests or anything like that but you said no. Ann Woodford 13 AW: No. RC: You read into it but not… AW: None at all. RC: So did you graduate from Ohio University? AW: I did, with a bachelor of fine arts degree. I was an honors student up there too because of Allen High School and because of my teachers at Andrews. You do well! You're not going to play around, you are going to study. RC: Through the… back to that Remembering Jim Crow book, I was curious about any time in Allen, or any time in Andrews, or up in Ohio, interracial dating or anything like that ever, did you ever see any of that? AW: It was completely interracial dating at Ohio. But here, when I was growing up here, I don't recall any interracial dating. But I know that white men had children by black women, here ... And I can't say that it wasn't vice versa but I just didn't know about it. RC: And then at Allen, none of your classmates with white boyfriends or anything like that? AW: None that I know of. RC: That's just one of the things that, like if you look at Jim Crow, that was one of the things that they were most scared of. Was especially African American men, that white men pretty much did what they wanted throughout history. AW: Yes, that's right. RC: Especially during slavery and even after. AW: Well right now, look at all the black men being shot. It's a shame. RC: But speaking like, dating and stuff like that. The white men were extremely scared of a black man and a white woman. Even if it was consensual, a lot of times they said it was rape. AW: To Kill a Mockingbird. RC: Right, there's plenty of, that's just if you look throughout history, history in the South, you know. That was one of the things that always comes up. And I was curious if that was ever apparent here or anything like that. AW: Not that I know of, like you said insulated, yes I was. Ann Woodford 14 RC: So in Andrews there were no… the Klan, was that, had you ever heard of it being active around here or anything like that? AW: I never heard of it, but a story was told and my dad told it too, that white people have told me this story, that after I went away, I don't know whether this was in the 80s but I think it was somewhere around the 80s. Ku Klux Klan decided they were going to come in here and get a Klan group started. RC: Klavern or whatever they call them, AW: Yeah, exactly. They set up their place over there in Peachtree and it was a trailer they tell me. And I can't prove this, but I should go back and look and see if anything in the newspapers but I never did do that. They set up their place over there and they were going to do a march through Andrews and Murphy. I don't know what happened in Murphy, but the stories that I’ve been told about Andrews is that there was a man in Happy Top who started to get his ammunition together, a black man. Who said they're not going to come up here starting anything because I'II blow them away. And he was… RC: That was one of the biggest ways of resistance, just get a gun. AW: Yes. Exactly right. So my dad said that's only going to start trouble, you need to leave that alone. Well he told Daddy off and put Daddy in his place and said I'm doing to protect myself and my family. So Daddy came downtown, and he had become a more calmer man. He came downtown and he went up and down the streets and talked to the store owners, and Ingles, and said if you close down during that there won't be any reason for people to come to town. Let it be known that you're closed. When the Ku Klux Klan marched down through town there was nobody much out there to see them, RC: Because they just closed down. AW: Yes, and when they went back to Peachtree their trailer was turned over. So it wasn't black people, black people didn't live in Peachtree. So that still makes me feel good about our people in this little mountain region right here, that they were not for having Klu Klux Klan group here. Now there were some people, Nord Davis and his group, and if you were to look him up and look what happened over in Franklin. RC: How do you spell that? AW: N-o-r-d, He was a very racist person who was one of those people that they call them survivalists. And he brought… Bo Gritz was running for government, I don’t remember what position he ran for once, but Bo’s people were here, and there is probably still an undercurrent of that somewhere, I don’t know, they don’t show themselves that way. But if you find Bo Gritz and Nord Davis, and there's another man I can't think of his name, over in Macon County. Boy they were against black people. They were even trying to build a school in Macon County to train young white men how to hate and what to do against African Americans or any minorities. Ann Woodford 15 So it didn't go through, to build that school and have it active. I don't know why. I haven't had enough chance to go back and research that. RC: And back to the Allen Home. I am curious regarding, so that education it sounds to me it's more of a Du Bois kind of model, like where it's kind of a talented tenth, are you familiar with that? AW: No. RC: The big, after or during Jim Crow and everything, there were two, from what I understand there were mainly two kind of ways, philosophies on educating African Americans. Booker T. Washington was, he wanted to basically do trade schools and Du Bois wanted it basically have a talented tenth, to lead, to help bring up other African Americans. It was big debate because Du Bois definitely didn't want, because Washington basically it was almost sticking with the status quo of just labor and stuff like that, but he believed that was the best way to exist and kind work up from there. But Du Bois wanted to educate in fine arts and social sciences, stuff like that and Washington was more trade schools. It just seems that the Allen Home was a very Du Bois like it wasn't like trade school. AW: No, but it started as trade. In the beginning, it started out training black women, young girls to be domestic workers. RC: And when was that? AW: It's in the book and I can't remember the date right now. When they started and I think said that in this writing but I'm not sure, we had to take a lot out because you could imagine how much more there was to write about and I was not an historical writer. I decided it had to be done, nobody else was going to do it, so that's why, this is the book here. RC: So it started out as a… AW: Training ground for RC: Training school essentially. Okay, and then it moved toward… AW: But they wanted them to be educated because they wanted them to be domestic workers for the wealthy of Asheville. They would have made more money and you know, had more prestige. A black woman that worked for a very wealthy family, even in her community and her church would have been held higher than the other women who were just doing the regular work for, teachers. RC: Very interesting. AW: And you said that the Du Bois school, yes they wanted us to go into all kinds of, not trades, but professions. Ann Woodford 16 RC: Leadership. AW: Mhmmm, they wanted that. And we've had a lot as you could see. You saw the judge there. One woman in my class was the, in my class, was a real leading person in the black caucus, the, what do they call it the black caucus? But many people like my aunt who went to Allen High School, she went to work in the General Motors in Youngstown, Ohio. So a lot of people went to work up north. They went north after the tannery closed there was nothing for people RC: This was what years? AW: Anywhere, she would have gone, I graduated from 8th grade in 1961 and she was already up north as they say. So I think that my aunt was, her younger sister was three years younger than she, and I’m about ten years younger than the aunt that's still living. So it would have been somewhere from the 50s, and they moved north and went to work in steel plants. Daddy's brother went in the steel plants. They could make a lot of money up there that way, and they bought their own homes and property and everything when they got up there. RC: I'm just curious about when she moved because World War Two caused a great… both World Wars did, WWI and WWII caused a great migration of southern African Americans to northern cities. Because the wars, it opened up plenty of jobs and stuff like that, and it caused a lot of, kind of leading toward civil rights because they were fighting country where they were being oppressed, especially in the south. AW: There's a little story in there about that. My grandpa saying when he went and I think he left here in, he built the house up there in 1912 in that close area right there between twelve and fourteen. He went to the service and he stayed for four years so he got out in ‘19. He said when he left the white women were hugging him and patting him on the back, men were patting him on the back, shaking his hand saying, “Oh you know when you get back things are going to be so different for black men.” And he said it was worse because he was expecting it, if he had just kept his mind like we’ll come back and it's going to be the same it wouldn't have hurt him as bad, but it was much worse on him. And his daughter is 95, she's down in a nursing home down here and I go to see her all the time, my aunt. She didn't feel good about her daddy because he didn't have a lot of ambition she thought and he did a lot anyway, she just felt bad about him because of that I and think well hey, look what he went through. RC: I was, there's a book, it's a book about North Carolina. It’s over in Oxford, North Carolina I forget the name of it but it was talking about… it was similar to that, it was basically that there were three types of African Americans. The ones that were just kind of, just kind of accepted it, then those who fought against it, and those who were kind of in the middle. There were a lot, just because of the system, a lot just accepted it, that was the whole point of the system, essentially to make them accept. Back to slavery and then Jim Crow. I've just found that interesting. AW: Well its good. I'm glad that you're studying this because there's so much that, you're trying to zero in Allen School right now, but at the same time you're learning all of this other stuff. Because redevelopment was one of the things that really look at Asheville. They decided to redevelop the street market, that street down in… Eagle… Eagle Market Street, they decided to Ann Woodford 17 redevelop. There were businesses, a lot of black businesses in there. There were shoe stores, shoe repair stores, barber shops, little grocery convenience type things. All of this was going on in there, and when they redeveloped and came back, the prices were so high and they had already lost their business while they were building that it killed business. That happened in Pittsburgh too when I was up there and they did the same thing. Also in places like Pittsburgh they built these high rise buildings with… on a little piece of land, and all these people, kids, women, and children. All these kids, where were they to play? They made fun, in the newspaper they made comments about how terrible it was that they tore the grass up. Where were the kids going to play? They tore up the grass they left trash out. They didn't have trash cans out there for them. Where were the going to throw their cans when they drank their sodas? So they did tear it up. But all the way through, what you've seen in this study and what you will continue, if you continue on it is, sometimes you almost feel like black people don’t have a chance. Even right now with the new President and the people that he has brought in as his top advisors, the top five that he's brought in. They all have a history of racism. And you know, he's our president. He is my president, he's your president. We might as well face it. But at the same time you think, what is this going to mean to black people? You know he's talked about, and I think he will change, but sending all the Latinos home. But look at all the Canadians that are here that are not legal, look at all the east Europeans that are here, the Russians that are here that are not legal. What if he chose to pick everybody that was not legal and send them all home it would be one thing, but he has zeroed in on the Mexicans. And so, if you're black and you think, which most of the ones around me that I know are thinking, they understand that. We can't be against Mexicans, you can't do that because you're talking about yourself. It's rough. RC: Just to close it up. Is there anything that you want to add, just anything that you think is relevant to this study that you would like to add? AW: The most relevant thing is that it takes people like you, and people like me working together to learn about each other. We must learn about each other. And then we will understand each other better. So yesterday I talked with a young black man over at Tri County and he made a statement that I'm trying to make sure I remember. I’m going to say it over and over to myself to try to remember it. Just because a thing is not understood does not meant that it can't be understood. Or that just because you don't understand something doesn't mean it can't be understood. That is so important, but the way it is here, is there is, I want to explain it right so you that you understand what I'm saying. If you are white in Andrews, you never have to think about going into any place, doing anything, no matter where you walk or go to another state or whatever. Everything is open to you and you come back to Andrews, this is a white town if you take it that way. But every black person that I know thinks about being black anyway, so therefore right now when they have plays and they have all kinds of events in town and they say, well why don't the black people come. Because they weren't welcome to go to places in the past so they've created their own familiar… RC: Institutions. AW: Yeah church, home, families tight together and that kind of thing. And so I want us to tear those barriers down. I want us to be able to say, you can go downtown to any place and go in and buy something and be paid, and have the money, if you're going to hand the money in the hand Ann Woodford 18 of a white person put the money in the hand of a black person. I want to see that. I'm not saying it's not done because I see every now and then young people, that sort of throw the money on the counter and are like they are scared they are going to touch me. Every now and then I see that, and it hurts me real bad when I see young people like that because they've had a chance to learn more than some of the older people, but that's it. Let's tear down the barriers. Let's love each other, that's the big thing. RC: Yep, yes ma’am. END OF INTERVIEW

Object

Object’s are ‘parent’ level descriptions to ‘children’ items, (e.g. a book with pages).

-

Ann Woodford discusses race relations in Western North Carolina under Jim Crow. Woodford explains and explores the importance of African American communities and institutions such as churches and schools especially under racial oppression.

-